Abstract

An agent is an autonomous computer system situated in an environment to fulfill a design objective. Multi-Agent Systems aim to solve problems in a flexible and robust way by assembling sets of agents interacting in cooperative or competitive ways for the sake of possibly common objectives. Multi-Agent Systems have been applied to several domains ranging from many industrial sectors, e-commerce, health and even entertainment. Agent-Based Modeling, a sort of Multi-Agent Systems, is a technique used to study complex systems in a wide range of domains. A natural or social system can be represented, modeled and explained through a simulation based on agents and interactions. Such a simulation can comprise a variety of agent architectures like reactive and cognitive agents. Despite cognitive agents being highly relevant to simulate social systems due their capability of modelling aspects of human behaviour ranging from individuals to crowds, they still have not been applied extensively. A challenging and socially relevant domain are the Disaster-Rescue simulations that can benefit from using cognitive agents to develop a realistic simulation. In this paper, a Multi-Agent System applied to the Disaster-Rescue domain involving cognitive agents based on the Belief–Desire–Intention architecture is presented. The system aims to bridge the gap in combining Agent-Based Modelling and Multi-Agent Systems approaches by integrating two major platforms in the field of Agent-Based Modeling and Belief-Desire Intention multi-agent systems, namely, NetLogo and Jason.

1. Introduction

An agent is a purpose-driven entity that interacts with its environment through its perceptions and actions in a persistent, rational and autonomous way [1,2]. Agents hold different roles and exhibit distinct sets of capabilities and decision-making models. A Multi-Agent System (MAS) is an assembly of several agents having either homogeneous or heterogeneous architecture [2,3]. MASs are applicable in a variety of contexts and for different purposes, being capable to model social structures with a high level of realism.

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) is a technique that facilitates directly representing the elements of a system including their relationships and interactions over time. ABM is becoming the de facto tool to develop simulations applied to a wide range of domains and to explore and validate social theories [4,5,6].

Either in an MAS or in the context of an ABM, an agent can represent an individual, a group or another kind of collectivity like dedicated staff, departments, unions or entire organizations.

Diverse types of agents have been used as the constituent elements of ABM/MASs to represent social or natural systems.

- Reactive agents are useful due to their simplicity in construction and their flexibility to act in dynamic environments.

- Cognitive agents are based on a more complex design that achieves a more robust architecture. They can also reason about the state of the environment to reach a goal-driven behaviour helpful to model either individuals or crowds.

The main type of agents used in ABM is the reactive one. A reactive agent can be developed by a set of rules if-then-else (better known as productions) or finite-sate machines that can conform a complex net to implement the set of required behaviours. One of the most noteworthy proposals to create reactive agents is the subsumption architecture that enable to build real-time responses while the agent is situated in a dynamic environment [7,8]. Such simplicity makes reactive agents very successful and widely used. However, reactive agents work based on limited information and fail in reasoning further their perceptual information, a wrongly working sensor could mislead the agents that cannot easily recover from such a failure as re-planning is not present [8].

However, the need to model social complex systems pushes towards considering more powerful models to represent human behaviour, and cognitive agents offer an alternative to help with pursuing this purpose.

Belief–Desire–Intention (BDI) is the most well-known architecture to develop cognitive agents [9], which represents agents as having beliefs, desires, and intentions that emulate aspects of human behaviour [10]. Beliefs are the real status of an agent in a certain time, i.e., the information and knowledge either external or internal the agent can manage; desires are the goals or states to achieve representing its design objectives; and intentions are the set of actions to perform in order to accomplish the agent’s goals [4,9,11]. A BDI agent drives its behaviour by selecting plans accordingly to its intentions in response to a certain event or goal. A plan is the representation of the procedural knowledge and capabilities the agent has at its disposal. Several plans can react to the same event or goal. Actions and subgoals are the building bricks of plans and they directly affect the environment in some way, possibly changing the state of affairs in it.

Despite Agent-Based Models being a sort of MAS, both communities have been evolved in independent ways with sparse mutual interaction [12,13]. This situation should be amended in order to exploit the knowledge developed by the entire agent-related community for its own sake. The importance of such an integration can be beneficial in at least two ways [12,13]:

- The work developed on MASs offers more sophisticated agency architectures than those used in ABM.

- ABM can be benefited from the strategic selection of agent’s behaviours that MASs make available.

In both cases, BDI architecture is suitable to be used because of its flexibility to define agents with a higher level of knowledge representation and deliberative capabilities exhibiting enough reactivity to cope with dynamic changes.

Disaster-Rescue (DR) simulations is a very active field on its own with many research and technical conferences, ranging from pure computational approaches to considering simulations as an in silico tool to help determine actual policies of action for emergency recovery and management in real life [14]. DR simulations have been deployed in the academic, government and private sectors supporting contingency anticipation, planning and policy making.

Due to this work aiming to progress in the integration of aforementioned techniques, an MAS applied to the DR domain involving cognitive agents based on the BDI architecture is presented. The system combines an environmental representation with BDI agents and represents a novel integration of two of the main platforms for ABM and Belief–Desire–Intention multi-agent systems development, namely, Jason and NetLogo.

2. The Disaster Rescue Problem

ABMs can be fed with or be based on real data collected in the course of social research (demographic, economic, sociological, etc.). Hence, on the one hand, an ABM can be perceived as a microscope, as it allows the analysis of the most representative details of social entities or individuals and their relationships, while, on the other hand, it can act as a telescope, as it allows for observing the aforementioned features within a crowd/social setting and observe their evolution.

In the analysis presented by Hawe et al. [14] based on [15], the authors underlines that the emergency management cycle is composed by four phases:

- Mitigation: long-term risk management, sustained actions to reduce or eliminate the risks to people and properties.

- Preparedness: activities to improve the response/actions like planning and organising staff, equipping, training, exercising and evaluating.

- Response: the actual actions to tackle the emergency, like fire extinguishing, rescue of people and street clearance.

- Recovery: government authorities’ coordination, plan and program generation, and restoring environment and infrastructure.

ABMs have relevance mainly during the phases of Preparedness and Response [14]. Concretely, Agent Based Simulation tools provide the following contributions on the aforementioned stages [14]:

- Planning: determining the impact of a disaster event identifying the ways to be prepared and how to respond.

- Vulnerability analysis: evaluation of the strategies of emergency response.

- Identification and detection: determining the occurrence possibility of a disaster.

- Training: training emergency services staff by simulation.

- Real-time response support: determining alternative response strategies given an emergency situation.

The work presented in this paper is applicable to the Planning and Training phases.

The DR problem is considered as an MAS problem since it implies the design of coordination strategies and communication between agents [16,17,18]; furthermore, a central point is to define agent architectures to cope with it. [14,18,19]. On the other hand, ABM are proposed as systems aiming to solve the DR problem from the point of view of simulating the human response facing a particular disaster or even combined calamities [5,14].

In computational terms, the DR problem can be stated as follows: [16,18]:

Given an environment that simulates a city or location under disaster conditions (earthquakes, fires, etc.), a population is represented as a set of agents, divided into victims (civilians), and rescue agents, which help the victims to evacuate and avoid risks. Rescue agents coordinate their actions to minimize the damage, casualties and keep civilians in safe conditions, possibly by joining forces, under uncertain and changing conditions where time is restricted.

This is a Coordination Problem [8,17,20,21] that has been commonly treated as a Task Allocation problem (which includes some variants as Social Welfare Maximization, and Coalition or Team Formation [22,23]). This problem involves of a strategy to organise rescue teams (brigades, ambulances, or fire brigades). The main activities of the agents are moving and searching (searching for victims/people) and performing rescue tasks (detection of victims, fires, and street blockades; temporary saving; evacuating people, among others).

Furthermore, the environment poses a very challenging scenario: time restricted, partially accessible (i.e., agents have limited capacity to observe), dynamic and may only be traversed in a reduced way. It is common that agents have limited or partial communication (to simulate failing infrastructures) with typically large numbers of agents (200 and above). Although most of the works have been based on reactive agents for such scenarios, some proposals have been put forward for using cognitive agents [24].

Due the advantages of cognitive agents, we are concerned with the case of MAS composed by BDI agents in the DR domain adopting a decentralised approach to organise the tasks of the agents.

3. Integrating ABM and BDI MAS: Jason and NetLogo

According to [4,10,14], JADE, Jadex, NetLogo, and Jason are the most noteworthy platforms to MAS development (including BDI agents) either for general purpose systems or to be applied in complex context such as those typically addressed by ABM, which comprises the Disaster Rescue Domain.

- Jason [25] is a full-fledged platform that enables the implementation of BDI agents with many user-customisable features including Java-based environments and legacy code. Jason is a very convenient framework given its robustness, more strict implementation of the BDI principles and the facilities of AgentSpeak as a higher level agent programming language.

- NetLogo [26] is an MAS programmable modeling platform for simulating social and natural phenomena given the facilities to represent different kinds of reactive agents and its power and easiness in defining and rendering rich environments with different features.

In this work, a simple BDI MAS applied to the DR domain was implemented exploiting the Java-based environments in Jason that allows the interaction with the BDI agents with other systems, and the possibility of NetLogo to receive external commands to drive its functioning. The interoperability of both platforms is warranted, given the facilities they offer through their API interfaces. There are two possibilities to pursue the connection Jason-NetLogo: either to include Jason into NetLogo, using just the Jason BDI engine or including NetLogo in Jason, using the former as the environment. Both options are briefly described as follows:

- Jason-into-NetLogo. Only use the Jason BDI engine. The following packages are used in doing so:

- Extend the Jason class AgArch (package jason.architecture) to create the Jason agent and manage its reasoning cycle. An additional package is also required: RunCentralisedMAS belonging to jason.infra.centralised.

- From the NetLogo side, to execute the NetLogo GUI with the model, org.nlogo.[lite,headless,api] packages and InterfaceComponent, HeadlessWorkspace and CompilerException classes are required.

- NetLogo-in-Jason. NetLogo is included as an Environment in Jason. To do so, it is required to use the following facilities:

- Perceive the environment—by extending the class Environment of the Jason architecture package jason.environment to transform the perceptions taken from NetLogo into readable literals for Jason’s agents according to the AgentSpeak semantic definition, in order to be inserted in the agents’ beliefs base.

- Act in NetLogo. The InterfaceComponent of the nlogo.lite.InterfaceComponent package allows for sending commands to the elements of the model (turtles and patches).

- Load the NetLogo model as an environment in Jason using a JFrame. Complementarily, java.awt.EventQueue.invokeAndWait and java.io.[InputStreamReader, BufferedReader, IOException] are used to perform the interface and keep both platforms running together.

Integrating both approaches, ABM and MAS, boosts the resultant system by combining the modelling capabilities and more complex behaviours, like some aspects of human conduct in the case of BDI agents. The main advantages of integrating Jason and Netlogo are underlined as follows:

- NetLogo is highlighted by the deliberation process of BDI Jason agents that enhance the capabilities of the pure reactive NetLogo turtles going beyond the pure quantitative heterogeneity (variations in the values of their parameters and variables).

- Jason can be enriched in at least two aspects:

- -

- By including a powerful environments rendering tool and the capability to easily interact with it through the avatar-like Netlogo turtles.

- -

- By inheriting the skills and functionalities already present in the turtles useful to define lower level tasks, for instance navigation and sensing.

- Both tools can be combined with other systems to manage more than one user-defined environment.

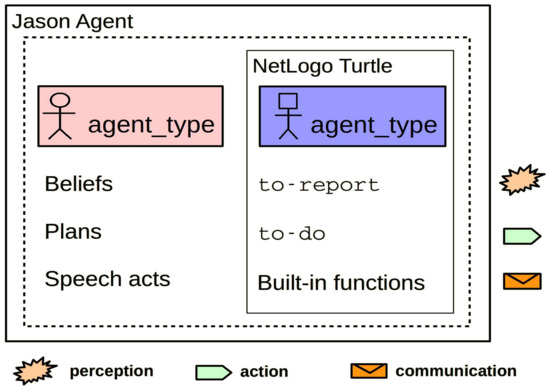

The capability to define reactive agents besides BDI agents working altogether in the same system makes it possible to combine features and abilities belonging to both kinds of agents. For instance, a Jason agent that is provided with BDI plans can exploit the reactive functions implemented in its belonging NetLogo turtle: to-do to act directly in the environment and to-report to perceive the current state of affairs resulting in an updating of its beliefs and possibly triggering other plans. No need to say, both agents can exploit the set of methods and functions defined in their correspondingly framework, including their communication systems where the expressibility of their higher and lower level representations (defined by speech acts in Jason and built-in functions in NetLogo) can be exploited as required. In Figure 1, this composition is depicted.

Figure 1.

Jason agents are enriched by using the reactive and lower level capabilities of its avatar-like NetLogo turtles and the latter are powered by the BDI reasoning loop of Jason agents. Executing BDI plans results in calling NetLogo functions to act, to perceive or to communicate with others.

This conveys the flexibility to define and represent the elements and entities of a simulation, i.e., there is a need of having purely reactive agents to represent environmental elements (like fire) and simultaneously agents with more robust deliberative processes are required to represent human individuals/organizations (like fire-fighters).

Table 1 summarizes the advantages of interconnecting Jason and NetLogo (J+N) contrasted with both tools taken in isolation (any feature can be exploited separately or in a combined way in J+N).

Table 1.

Main advantages of integrating Jason and NetLogo. R = Reactive agents, C = Cognitive agents, Ex = External environment, Cn = counterpart agent representation, L = Legacy code, S = Plotting and Statistics.

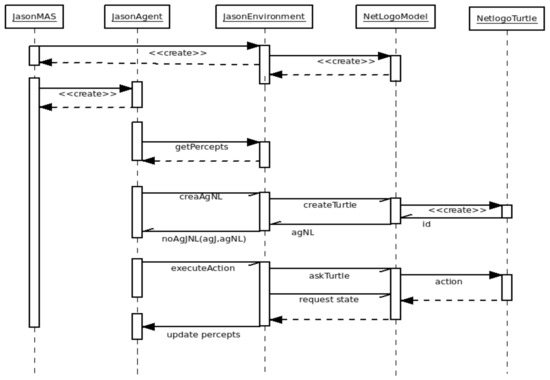

The NetLogo-in-Jason option, besides being the natural way to implement our ABM, constitutes, to our best knowledge, a novel contribution in MAS development. Figure 2 depicts the interaction diagram in UML. As can be seen, both systems interact with each other through their corresponding APIs, allowing the Jason agents to act in the environment using the NetLogo turtles and updating their percepts by means of requesting the execution of actions and updates about the current state of the environment.

Figure 2.

Sequence diagram in UML of the Netlogo-in-Jason interconnection option.

In both of the integration cases aforementioned, in order to send perceptions and receive actions from the environment to Jason’s agents and vice versa, a process of translation from the NetLogo list-based representation to the AgentSpeak Prolog-like representation have to be done. Thus, the following classes are required: Agent, ActionExec, TransitionSystem, Literal (contained in package jason.asSemantics). In Table 2, some of this translations are presented regarding some sensing and acting commands. The translation procedure is carried out by the environment Jason Java classes and it is not detailed here for the sake of simplicity. In brief, an AgentSpeak literal was introduced in the Jason side to denote when the agent is sending a command to the environment: sendCmdNL/2 which arguments are the agent ID and the intended command. The agent ID is a number identifying the turtle in NetLogo that act on behalf of the Jason agent. The command is a string that identifies the action to be pursued, which is sent to the Jason Java class Environment and translated to the NetLogo final command.

Table 2.

Examples of the translation of perceptions and commands from Jason to NetLogo and vice versa. NetLogo identifiers: AgNL: a turtle, ID: a fire, and agName: the corresponding Jason agent.

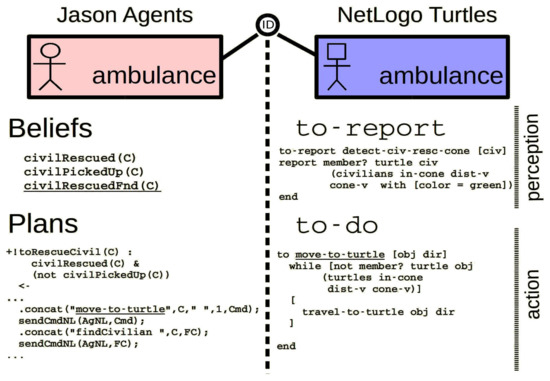

In Figure 3, an example of the integration of Jason and NetLogo agents is illustrated. The BDI plan !toRescueCivil(C) belonging to a Jason agent ambulance take advantage of the reactive capabilities of its correspondingly turtle by calling the function move-to-turtle in order to locate and go to the required position of a detected victim denoted by C, i.e., the ID of the turtle representing the victim. The reactive function on its turn calls another function named travel-to-turtle that directly used the native NetLogo functions available to move towards the position of a given turtle ( takes the value of C). On the other hand, the result of detect-civ-resc-cone will result in a belief updating adding civilRescuedFnd(C).

Figure 3.

Jason agents act and perceive by means of their turtle counterpart in the environment. The BDI plan !+toRescueCivil(C) triggers the execution of function move-to-turtle providing the required input, i.e., the ID of a victim stored in C. The NetLogo function detect-civ-resc-cone will result in the updating of civilRescuedFnd(C). The underlined text is just for easy reading.

The design of the BDI MAS was performed using the editor Prometheus Development Tool (PDT) [27] as it has been conveniently used in the Jason development [28]. The set of agents specified in Jason are situated within an environment defined by a NetLogo model inspired by two models: city traffic [29] and a rescue environment with no map rendering and no restriction on the agent movement [30]. In order to develop a realistic disaster rescue scenario, we undertook the following:

- A map of a given city is rendered using the gis extension of NetLogo that represents the pixels as patches in the model. Buildings and streets are segmented to allow the agents to move only through the latter.

- Elements of the environment are represented in NetLogo as breeds of turtles (agents). Objects: one base, obstacles, fires, blockades; people: victims (civilians) and rescue staff (ambulances, rescue-units, fire-brigades and police).

- Rescue staff is also represented as BDI agents in Jason. turtles act on behalf of Jason agents, i.e., the higher level decision-making is on the Jason side. Lower level functions (such as navigation) are managed in NetLogo. Rescue agents have a narrow sight of view of 10 pixels ahead in an angle of 90 degrees.

- Objects and civilians have behaviours not governed by Jason.

The DR BDI Simulation

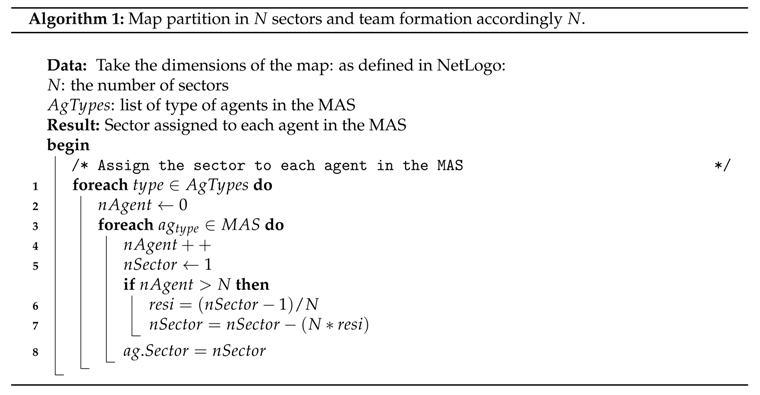

The purpose of the simulation is to test the integration of Jason and NetLogo. A basic policy of task allocation is implemented based on dividing the map in N sectors where the agents can operate (Algorithm 1). Then, the team formation is performed by assigning agents to each sector. To have similar number of agents in each sector, the teams are formed accordingly with the number of agents modulo N (experimentally set to 4). These directions are integrated into the start plan of each agent as an initialization stage, just before the creation of the NetLogo turtles.

The system as a whole behaves in a decentralized way as no agent leads the teams or the activities. The brigadier and other agents message each other only when a target is found. The measure of the global behaviour of the system consists of counting the rescue actions, and the number of actions performed in the environment. In this manner, to indicate the Performance , only a ratio of the number of rescue actions (where: ) with respect to the total number of actions is provided, and it is computed accordingly with Equation (1):

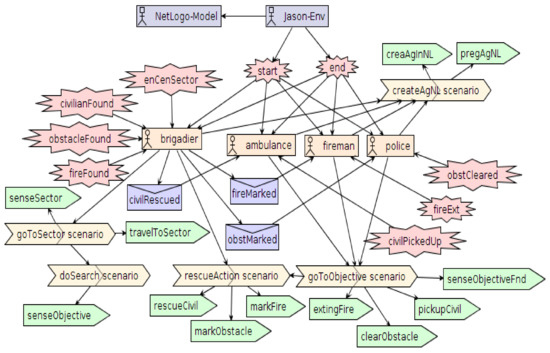

Figure 4 shows the Prometheus Analysis Overview Diagram, which represents the global design of the MAS, the agents and their interaction with the environment, and the perceptions coming either from the environment or by messaging using the Jason communication facilities.

Figure 4.

Prometheus Analysis Overview Diagram of the Disaster-Rescue BDI MAS.

In each process of sensing or acting in the environment, Jason agents act through its turtle performing the actual action on the environment, like the rendering of the image to illustrate its movements traversing it, and many others.

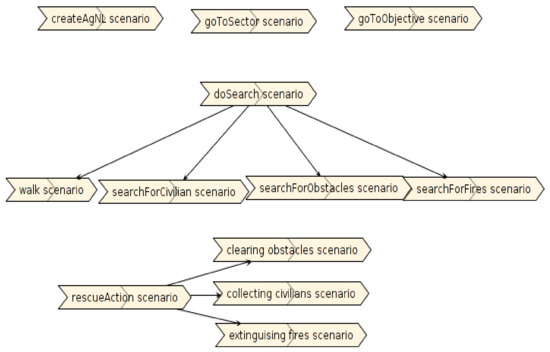

In the Prometheus methodology, scenario stands for an abstract description of a particular sequence of steps within the system. The scenarios of the system are depicted in the Scenario Diagram showed in Figure 5, and are described in brief as as follows:

Figure 5.

Prometheus Scenario Diagram of the BDI Rescue MAS.

- createAgNL: Create the NetLogo turtle to be used as an avatar in the NetLogo environment by Jason Agents.

- goToSector: Brigadier agent goes to its designated sector (1 of N), which is selected accordingly with the module of N of their number of agent.

- doSearch: Brigadier agents perform the searching of: civilians, obstacles and fires in their designated sector. Once an objective is found, it is added as a belief and the suitable agent is notified about it. It is divided in the following scenarios:

- -

- walk: Brigadier agents move through their designated sector.

- -

- searchForCivilian: Brigadier agents sense the environment looking for civilians.

- -

- searchForObstacles: Brigadier agents sense the environment looking for obstacles.

- -

- searchForFires: Brigadier agents sense the environment looking for fires.

- goToObjective: An agent traverses the environment looking for the objective (civilian, obstacle or fire) to perform rescue actions.

- rescueAction: Once the agents reach their current objective (within its scope given by distance and sight cone parameters in NetLogo), they perform, rescue, clear, pickup, or extinguish actions. It is divided into the following scenarios:

- -

- clearing obstacles: Agents act on a target performing clearing actions.

- -

- collecting civilian: Agents act collecting civilian actions.

- -

- extinguishing fires: Agents act extinguishing a targeted fire.

A brief description of the system functionality is listed as follows:

- starts

- starts

- starts

- sends start perception to

- initiate the createAgNL scenario

- acts guided by its own individual behaviour accordingly to the type defined by its , where

- stops when either the total of civilians are rescued and collected, all fires are extinguished, and the obstacles cleared, or a threshold for the number of actions is reached

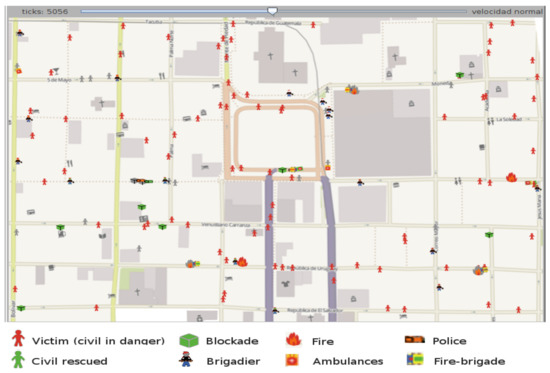

Figure 6 illustrates a screenshot of the BDI MAS running with 16 brigadiers, four ambulances, police and fireman, 10 fires and obstacles and 45 civilians.

Figure 6.

The Disaster-Rescue BDI MAS running with a map of the main square of Mexico City. Gray coloured objects mean rescued civilians, cleared blockades and extinguished fires.

4. Experiments and Results

The experiments are focused on the interaction between NetLogo and Jason for the purpose of illustrating the feasibility of the platform to scale regarding the number of agents performing rescue actions. Two sets of experiments were performed, varying the number of agents reported.

The first set was run on an Dell Optiplex 7010 Core i5 CPU with 8GB of RAM with Ubuntu 14.04.5 LTS In Table 3, a summary of the system running with a different number of agents is presented. Rescue actions do not increase while increasing the number of brigadier agents, but they do decrease the searching time. On the other hand, increasing the number of collecting agents (police, fire brigades and ambulances) reflects a positive change in the number of rescue tasks performed. The performance defined in Equation (1) provides a look at the number of pursued rescue actions when the system reaches the maximum of 50,000 actions per run. In the case of run Av250, increasing the number of rescue staff tends to increase this ratio as the number of expected actions is higher than the other runs because of the large number of civilians.

Table 3.

Averages of runs up to 50,000 actions with variations of the number of agents. Av[16,200,500]: ⟨{A, P, F = 4}, {B = 16, 200, 500}, {K, R = 10}, V = 45⟩ 10 runs. Av250: ⟨{A, P, F = 16}, {K, R = 10}, B = 50, V = 250⟩ 5 runs. Letters stand for: B = brigadier, A = ambulances, P = police, F = firebrigade, K = blockades, R = fires, V = victims.

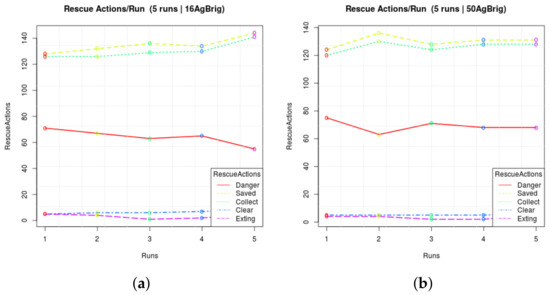

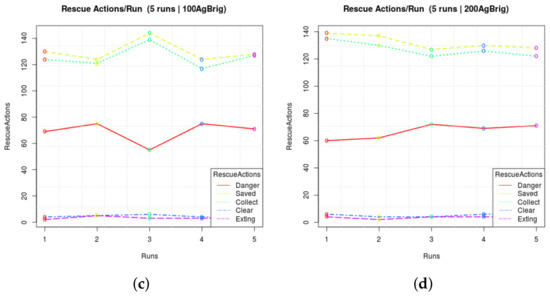

In the second set of experiments, the system ran on a Dell Vostro 3750 Core i7 CPU laptop with 10GB of RAM with Ubuntu 14.04.5 LTS. Figure 7 shows a view of five runs of the system up to 50,000 actions with the following configuration of agents: fire (10), blockades (10), victims (200), police (4), ambulances (4), and fire brigades (4). Only brigadier agents were varied: 16, 50, 100 and 200. The figure shows a plot of rescue actions fulfilled by the MAS (people in danger, saved or collected; blockades cleared, and fires extinguished), where the y-axis defines the number of rescue actions performed by the system and the x-axis is the number of runs.

Figure 7.

The MAS BDI performance of five runs with different rescue staff: (a) 16 brigadiers; (b) 50 brigadiers; (c) 100 brigadiers; and (d) 200 brigadiers. The rest of agents remain constant: fire (10), blockades (10), victims (200), police (4), ambulances (4), and fire brigades (4).

As can be seen in the lines of the plots, the system behaves in a similar way during the runs despite the variation of the number of agents representing the rescue staff. The circled spots in the lines belong to the number of actions reached by the system in a particular rescue action after completing a cycle of 50,000. For instance, in (a), the number of people remaining in danger varies from 63 to 75 victims, while the people saved ranges from 128 to 136.

Averages of rescue actions reached in each 5 runs per number of brigadier agents is showed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Averages of five runs of the BDI MAS up to 50,000 actions. BA stands for Brigadier Agents.

In the first experiment, summarized in Table 3, the observed correlations between the number of brigadier agents (from 16 to 500) and the rescue actions indicate that there is a positive effect by having more agents looking for victims: 0.9808 for people in danger (Danger) and −0.9808 for saved victims (Saved), while collected people (Collect) exhibited −0.9789. The cases of clearing blockades (Clear) and extinguished fires (Exting) reached −0.789318 and 0.1947211, respectively.

Taking the averages of the second experiment (Table 4) to calculate the correlation between the variables, it can be seen that there is a weak correlation between the increased number of brigadier agents (BA) and the number of rescue actions to save people, and very low correlation with clearing obstacles and extinguishing fires. In the case of Saved, it is −0.2254 and 0.2254 for Danger, while Collect reported −0.4331, Clear −0.5272, and 0.5095 for Exting.

Needless to say, Saved and Danger have a correlation of −1 in both experiments as they are inverse to each other, while the correlations Collect/Saved were 0.9999 for the first experiment and 0.9756 for the second one. Collect/Danger showed −0.9999 and −0.9756 in the first and second experiments, respectively. Finally, the calculated correlation between Exting and Clear was −0.7559 in the first experiment and 0.3244 for the last one, which can be considered acceptable as no dependence is expected on those values.

The results of both sets of experiments are consistent about the scalability of the integration of Jason and NetLogo while working with variations in the number of any kind of agents. This consistency holds also in the fact that, in the current implementation, in the event of a large population of victims, the mere increasing of the number of brigade agents does not suffice to increase in a significant way the execution of rescue tasks.

5. Discussion

ABM is a socially relevant application with many challenges from a computational point of view. In particular, utilising cognitive agents in ABM enables one to model and study more complex behaviours. However, implementing complex scenarios including cognitive agents still remains a challenge from a development point of view.

The interconnection of ABMs and MAS has been explored in other works. In [31], a very basic BDI implementation in pure NetLogo programming language is reported, mainly focused on teaching the MAS BDI foundations. This approach includes communication capabilities and a straightforward way to implement intentions (as a list of commands). However, being a basic implementation, it lacks a proper definition of plans and other facilities offered by other BDI oriented platforms.

Jack as the BDI platform and Repast as the ABM simulator are interconnected in the work reported in [32]. In this system, the agent reasoning and decision-making is kept in the BDI agents system side, while observing and acting in the environment remains in the ABM simulator. The domain of application is a version of the model RepastCity, where agents walk through the environment from a current location to diverse destinations.

In [33], an integration of BDI agents with GAMA, an ABM platform, is presented using its GAML modelling language, taking an agricultural related problem as the application domain. This work differs with ours mainly in the platforms used: Jack and Repast. About the domain of application, the disaster-rescue represents a bigger problem that subsumes the RepastCity domain at least regarding the traversing task of the agents. In [34], an extension to this work is showed aiming for a simple-to-use architecture (even by non-computer scientists) directed to modellers. In addition, it is flexible enough to enclose complex behaviours and a gold-miner simulation. Being an interesting approach from the point of view of the usability, this work relies on a still limited BDI architecture not usable for some applications.

In [19], a three-layered integration framework between BDI agents and ABMs systems applied to some domains including bushfire evacuation is presented. This work is mainly based on Jack as the BDI engine and MATSim as the ABM simulator. Through the three layers’ cognitive capabilities, application-specific code and the synchronization and communication between both systems is managed. The main difference with our work lies in the use of the BDI system as slave of the ABM as a means to control the time-step oriented functioning of the ABM system. Despite it being possible to use Jason/NetLogo in such a way, in the work reported here, the opposite option is used, as it is more natural for the sake of driving the turtles accordingly with the BDI cognitive capabilities, while the steps of NetLogo system are directly controlled by Jason.

In this paper, an implementation of a BDI MAS applied to the Disaster Rescue domain is presented. This aims to bridge the gap between the integration of ABM and MAS approaches through both of the main ABM/MAS development tools: NetLogo and Jason.

The BDI MAS uses a simple strategy of map partitioning and distribution of the rescue agents in the environment with communication capabilities and a simple task allocation policy. Environmental elements are represented as NetLogo agents while rescue agents are represented in both platforms giving the Jason agents the higher level task of reasoning and decision-making. In this way, NetLogo agents act in the environment on behalf of their counterpart agents in Jason. The systems scales well from a small population to a larger population of rescue agents, demonstrating the feasibility of integrating both platforms.

Some avenues can be explored to improve this work: (a) integrating a set of task allocation algorithms to be selected by the user and executed by the agents; (b) representing a large set of features for the environment elements such as fire propagation and fieriness, time alive for the victims, fuel decrease in the police and ambulance vehicles, among others; (c) including a partition algorithm to divide the scenario; (d) defining a set of metrics to measure the system performance as a whole and on the agent level; and (e) test the framework with other systems to exploit the possibility of both platforms of having more than one user-defined environment.

Finally, this work represents a step towards the development of DR Simulations based on BDI agents exploiting the powerful NetLogo environmental rendering facilities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to project No. 48510384 of SEP-DSA/UAM-169, for the support provided for this work.

Author Contributions

Wulfrano Arturo Luna-Ramirez worked on the theoretical part and the development of the system. In addition, he designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the manuscript writing. Maria Fasli is the supervisor for the lead author and contributed significantly to the conception of the proposed simulation. Additionally, she reviewed and edit the manuscript, and authorized the final version to be submitted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UML | Unified Modeling Language. A general-purpose, developmental, modeling language in Software Engineering. |

| API | Application Programming Interface. A set of libraries that allow interoperability between different software. |

References

- Fasli, M. Agent Technology for E-Commerce; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Wooldridge. An Introduction to Multiagent Systems; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Inteligencia Artificial: Un Enfoque Moderno; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kravari, K.; Bassiliades, N. A survey of agent platforms. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2015, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railsback, S.F.; Grimm, V. Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, M.; Gilbert, N. Agent based modelling. In Handbook of Quantitative Methods for Educational Research; Timothy, T., Ed.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. A robust layered control system for a mobile robot. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 1986, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Mustapha, A.; Mohammed, M.A. A Concise Overview of Software Agent Research, Modeling, and Development. Softw. Eng. 2017, 5, 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.S.; Georgeff, M.P. Bdi agents: From theory to practice. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems (ICMAS-95), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–14 June 1995; pp. 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Balke, T.; Gilbert, N. How do agents make decisions? a survey. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2014, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastani, M. A survey of multi-agent programming languages and frameworks. In Agent-Oriented Software Engineering; Shehory, O., Sturm, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia, D.; Nigel, G.; Wellman, M.P. Introduction to the special issue on autonomous agents for agent-based modeling. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2016, 30, 1021–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, M.P. Putting the agent in agent-based modeling. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2016, 30, 1175–1189. Available online: http://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/journals/aamas/aamas30.html#Wellman16 (accessed on 23 March 2018). [CrossRef]

- Hawe, G.I.; Coates, G.; Wilson, D.T.; Crouch, R.S. Agent-based simulation for large-scale emergency response: A survey of usage and implementation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2012, 45, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, G.D.; Bullock, J.A.; Coppola, D.P. Introduction to Emergency Management, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S.; Modanwal, N.; Mazumdar, B.D. Multi-agent based disaster management system: A review. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2011, 2, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano, H.; Tadokoro, S.; Noda, I.; Matsubara, H.; Takahashi, T.; Shinjou, A.; Shimada, S. Robocup rescue: Search and rescue in large-scale disasters as a domain for autonomous agents research. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Tokyo, Japan, 12–15 October 1999; Volume 6, pp. 739–743. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Modanwal, N.; Basak, S. Mas coordination strategies and their application in disaster management domain. In Proceedings of the 2011 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Agent and Multi-Agent Systems (IAMA), Chennai, India, 7–9 September 2011; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Padgham, L.; Logan, B. Integrating BDI agents with agent-based simulation platforms. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2016, 30, 1050–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, N.R.; Wooldridge, M. Agent-oriented software engineering. Artif. Intell. 2000, 117, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, R. Engineering Coordination: A Methodology for the Coordination of Planning Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, A.; Farinelli, A.; Ramchurn, S.; Shi, B.; Maffioletti, F.; Reffato, R. Rmasbench: Benchmarking dynamic multi-agent coordination in urban search and rescue. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-agent Systems, St. Paul, MN, USA, 6–10 May 2013; International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Richland, SC, USA, 2013; pp. 1195–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Gonzalez, M.; Cerquides, J.; Farinelli, A.; Meseguer, P.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, J.A. Binary max-sum for multi-team task allocation in robocup rescue. In Proceedings of the Optimisation in Multi-Agent Systems and Distributed Constraint Reasoning (OptMAS-DCR), Paris, France, 5–6 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Parunak, H.; Brueckner, S.A. Engineering swarming systems. In Multiagent Systems, Artificial Societies, and Simulated Organizations (International Book Series); Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 11, pp. 341–376. [Google Scholar]

- A Java-based intepreter for and extended version of AgentSpeak. Available online: http://jason.sourceforge.net/wp/description/ (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Wilensky, U. NetLogo. Available online: http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/ (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Padgham, L.; Thangarajah, J. The Prometheus Design Tool (PDT). Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/rmitagents/software/prometheusPDT (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Boissier, O.; Bordini, R.H.; Hubner, J.F.; Ricci, A.; Santi, A. Multi-agent oriented programming with jacamo. Sci. Comput. Program. 2013, 78, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffic Model. Available online: http://modelingcommons.org/browse/one_model/3851#model_tabs_browse_info (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Sakellariou, I.; Kefalas, P.; Stamatopoulou, I. Teaching intelligent agents using NetLogo. In Proceedings of the ACM-IFIP Informatics Education Europe III Conference, Venice, Italy, 4–5 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariou, I.; Kefalas, P.; Stamatopoulou, I. Enhancing NetLogo to simulate BDI communicating agents. In Proceedings of the 5th Hellenic Conference on Artificial Intelligence: Theories, Models and Applications, Syros, Greece, 2–4 October 2008; Volume 5138 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Darzentas, J., Vouros, G., Vosinakis, S., Arnellos, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Padgham, L.; Scerri, D.; Jayatilleke, G.; Hickmott, S. Integrating BDI reasoning into agent based modeling and simulation. In Proceedings of the 2011 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 11–14 December 2011; pp. 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Caillou, P.; Gaudou, B.; Grignard, A.; Truong, C.Q.; Taillandier, P. A simple-to-use BDI architecture for agent-based modeling and simulation. In Advances in Social Simulation 2015; Jager, W., Verbrugge, R., Flache, A., de Roo, G., Hoogduin, L., Hemelrijk, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Taillandier, P.; Bourgais, M.; Caillou, P.; Adam, C.; Gaudou, B. A BDI agent architecture for the GAMA modeling and simulation platform. In Proceedings of the Multi-Agent Based Simulation XVII—International Workshop, MABS 2016, Singapore, 10 May 2016; Revised Selected Papers. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–23. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67477-3_1 (accessed on 23 March 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).