Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort and Samples

2.2. Proteomic Data Generation and Preprocessing

2.3. The Synolitic Graph Neural Network (SGNN) Framework

2.4. Graph Feature Engineering and GNN Architecture

2.5. Graph Sparsification

- No sparsification: Baseline configuration that preserves the original graph structure.

- Threshold-based sparsification: Retains a fraction of the most significant edges based on the criterion , where is the edge weight. This approach allows control over graph sparsity while preserving connections with the greatest deviation from the neutral value .

- Minimum connected sparsification: Employs binary search to determine the maximum threshold such that the graph remains connected. The method finds the minimal edge set that ensures graph connectivity, thereby optimizing the trade-off between sparsity and structural integrity.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- •

- Primary Test Set: The fold held out from training in that cross-validation iteration. For individuals represented in this set, samples were collected less than one year before clinical diagnosis.

- •

- Early-Detection Holdout Set: Constructed within each fold by selecting the penultimate samples from the same patients whose final-visit samples formed the Primary Test Set. These earlier samples were collected one to two years prior to ovarian cancer diagnosis, providing a stringent assessment of the model’s early-detection capability.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

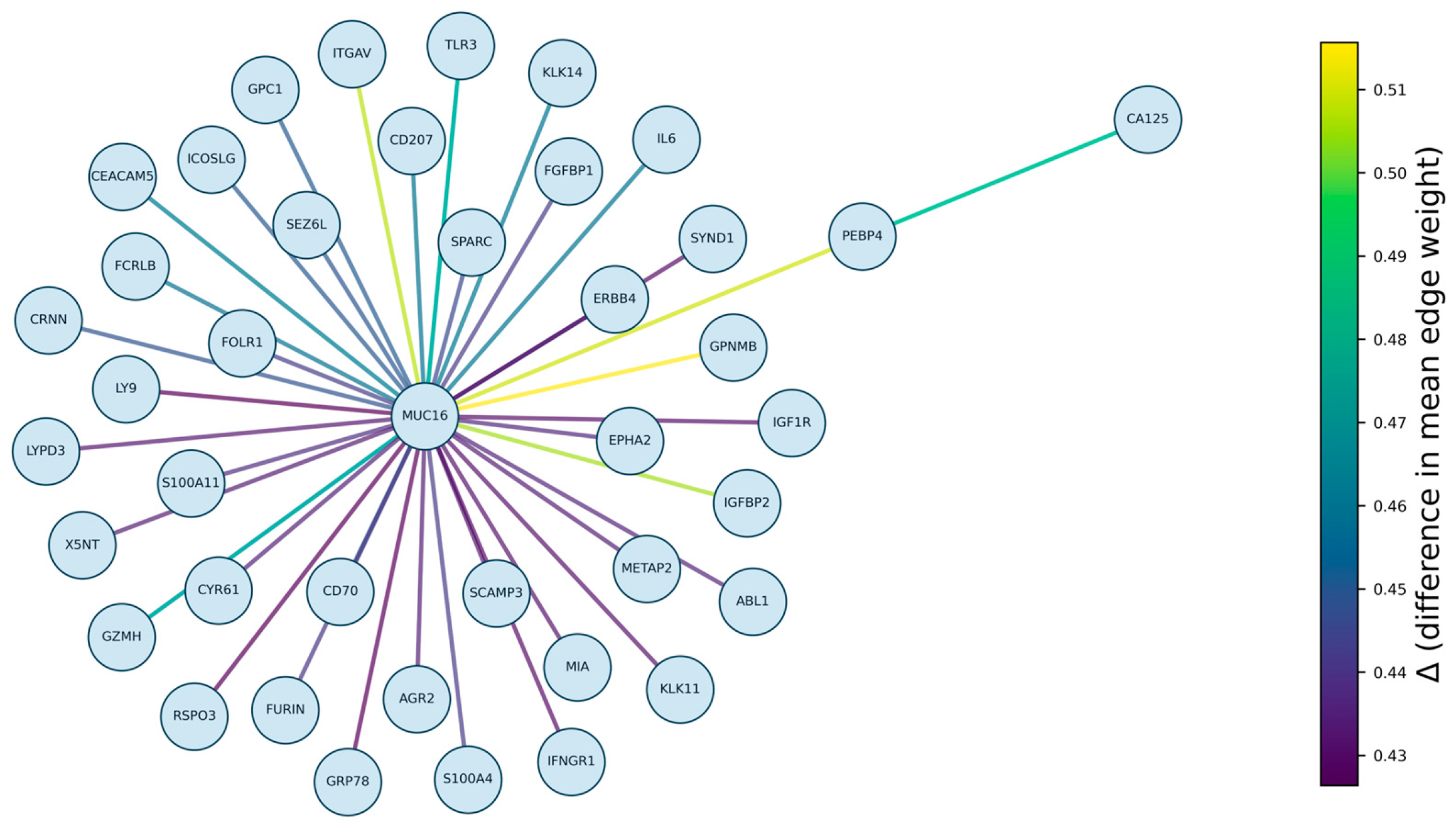

3.2. Visualisation of Case–Control Topological Differences

3.3. Model Performance Within 1 Year Before Diagnosis

3.4. Early Detection Performance (1–2 Years Before Diagnosis)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CRUK. Cancer Statistics: Ovarian Cancer Survival Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/ovarian-cancer/survival (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kurman, R.J.; Shih, I.M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: A proposed unifying theory. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshiyama, M.; Matsumura, N.; Konishi, I. Recent concepts of ovarian carcinogenesis: Type I and type II. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 934261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowtell, D.D. The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, I.; Bast, R.C., Jr. The CA 125 tumour-associated antigen: A review of the literature. Hum. Reprod. 1989, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, E.; Bodor, G. CA-125 concentrations in malignant and nonmalignant disease. Clin. Chem. 1991, 37, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.P.; Bourne, T.H.; Campbell, S. Screening strategies for ovarian cancer. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 10, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitawaki, J.; Ishihara, H.; Koshiba, H.; Kiyomizu, M.; Teramoto, M.; Kitaoka, Y.; Honjo, H. Usefulness and limits of CA-125 in diagnosis of endometriosis without associated ovarian endometriomas. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorp, T.; Cadron, I.; Despierre, E.; Daemen, A.; Leunen, K.; Amant, F.; Timmerman, D.; De Moor, B.; Vergote, I. HE4 and CA125 as a diagnostic test in ovarian cancer: Prospective validation of the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarojini, S.; Tamir, A.; Lim, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Goy, A.; Pecora, A.; Suh, K.S. Early detection biomarkers for ovarian cancer. J. Oncol. 2012, 2012, 709049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.G.; Miller, M.C.; Steinhoff, M.M.; Skates, S.J.; Lu, K.H.; Lambert-Messerlian, G.; Bast, R.C. Serum HE4 levels are less frequently elevated than CA125 in women with benign gynecologic disorders. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 351.e1–351.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.G.; McMeekin, D.S.; Brown, A.K.; DiSilvestro, P.; Miller, M.C.; Allard, W.J.; Gajewski, W.; Kurman, R.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Skates, S.J. A novel multiple marker bioassay utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 112, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, U.; Ryan, A.; Kalsi, J.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Dawnay, A.; Habib, M.; Apostolidou, S.; Singh, N.; Benjamin, E.; Burnell, M.; et al. Risk Algorithm Using Serial Biomarker Measurements Doubles the Number of Screen-Detected Cancers Compared With a Single-Threshold Rule in the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, H.J.; Worthington, J.; Blyuss, O.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Ryan, A.; Gunu, R.; Kalsi, J.; Menon, U.; Jacobs, I.; Zaikin, A.; et al. Improved Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer Using Longitudinal Multimarker Models. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, T.A.; Barraclough, D.L.; Rajic, A.; Dhulia, J.; Lewis, K.J.; Armes, J.E.; Barraclough, R.; Rudland, P.S.; Rice, G.E.; Autelitano, D.J. Increased plasma concentrations of anterior gradient 2 protein are positively associated with ovarian cancer. Clin. Sci. 2010, 118, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstrom, I.; Raycraft, J.; Hayden-Ledbetter, M.; Ledbetter, A.J.; Schummer, M.; McIntosh, M.; Drescher, C.; Urban, N.; Hellström, K.E. The HE4 (WFDC2) protein is a biomarker for ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3695–3700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bischof, A.; Briese, V.; Richter, D.U.; Bergemann, C.; Friese, K.; Jeschke, U. Measurement of glycodelin A in fluids of benign ovarian cysts, borderline tumors and malignant ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Havrilesky, L.J.; Whitehead, C.M.; Rubatt, J.M.; Cheek, R.L.; Groelke, J.; He, Q.; Malinowski, D.P.; Fischer, T.J.; Berchuck, A. Evaluation of biomarker panels for early-stage ovarian cancer detection and monitoring for disease recurrence. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 110, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukishiro, S.; Suzumori, N.; Nishikawa, H.; Arakawa, A.; Suzumori, K. Use of serum secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor levels in patients to improve specificity of ovarian cancer diagnosis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 96, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivonosov, M.; Nazarenko, T.; Ushakov, V.; Vlasenko, D.; Zakharov, D.; Chen, S.; Blyus, O.; Zaikin, A. Analysis of Multidimensional Clinical and Physiological Data with Synolitical Graph Neural Networks. Technologies 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Alon, U.; Yahav, E. How Attentive are Graph Attention Networks? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2105.14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Zaikin, A.; Sviridov, I.; Sosedka, A.; Linich, A.; Nasyrov, R.; Mirkes, E.; Tyukina, T. Overcoming the Curse of Dimensionality with Synolitic AI. Version 1. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating; Springer: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Adam, J.B. A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regiularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Blyuss, O.; Ryan, A.; Burnell, M.; Karpinskyj, C.; Gunu, R.; Kalsi, J.K.; Dawnay, A.; Marino, I.P.; Manchanda, R.; et al. Multi-Marker Longitudinal Algorithms Incorporating HE4 and CA125 in Ovarian Cancer Screening of Postmenopausal Women. Cancers 2020, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Hidden (embedding) size | 128 |

| Number of GNN layers | 2 | |

| Dropout rate | 0.30 | |

| Residual connections | True | |

| Attention-specific | Number of attention heads | 3 |

| Concatenate head outputs | True | |

| Edge features | Use edge encoder | True |

| Edge encoder hidden size | 32 | |

| Number of edge encoder layers | 2 | |

| Classifier head | Use classifier MLP | True |

| Classifier MLP hidden size | 32 | |

| Number of classifier MLP layers | 2 | |

| Optimization | Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | 1 × 10−2 | |

| Weight decay | 1 × 10−5 | |

| Regularization | Early stopping patience | 128 epochs |

| LR scheduler factor | 0.5 | |

| LR scheduler patience | 32 epochs |

| Model | Sparsity | ROC-AUC (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Feat. = FALSE | Node Feat. = TRUE | ||

| GCN | None | 66.83 ± 14.44/62 ± 20.93 | 72.17 ± 15.59/69.17 ± 16.12 |

| p = 0.2 | 66.67 ± 19.55/59.17 ± 15.05 | 62 ± 18.04/52.83 ± 17.52 | |

| p = 0.8 | 68.17 ± 16.29/65.53 ± 20.63 | 62.83 ± 18.85/56 ± 16.23 | |

| Min conn. | 56.17 ± 11.69/50.83 ± 14.22 | 56 ± 23.59/56.17 ± 16.33 | |

| GATv2 | None | 71.33 ± 24.68/53.67 ± 18.5 | 67.67 ± 26.13/58.33 ± 19.64 |

| p = 0.2 | 68.67 ± 11.69/56.33 ± 15.38 | 67.5 ± 13.67/60.5 ± 15.56 | |

| p = 0.8 | 55.33 ± 27.15/47.67 ± 16.9 | 51.33 ± 7.01/58.5 ± 14.27 | |

| Min conn. | 61 ± 13.25/58 ± 29.24 | 60.17 ± 19.4/71.17 ± 12.1 | |

| XGBoost | 92 ± 7.3/60.67 ± 15.53 | ||

| Random Forest | 84.67 ± 11.39/55.5 ± 15.92 | ||

| SVM | 78.5 ± 5.54/58.67 ± 14.84 | ||

| Logistic regression | 76.67 ± 17.8/66.67 ± 19.58 | ||

| Elastic net | 66 ± 13.05/73.17 ± 10.25 | ||

| Model Type | Sparsity | Node Feature | F1 | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | None | TRUE | 61.57 ± 3.5 | 81 ± 20.74 | 36.67 ± 32.06 |

| p = 0.2 | 53.95 ± 10.02 | 77 ± 22.8 | 20 ± 21.73 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 53.25 ± 12.28 | 70 ± 22.08 | 30 ± 29.81 | ||

| Min conn. | 48.67 ± 18.07 | 64 ± 39.27 | 40 ± 41.83 | ||

| None | FALSE | 65.04 ± 14.72 | 69 ± 24.08 | 66.67 ± 39.09 | |

| p = 0.2 | 58.46 ± 14.43 | 60 ± 23.45 | 63.33 ± 36.13 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 66.4 ± 8.58 | 77 ± 17.89 | 56.67 ± 30.28 | ||

| Min conn. | 52.19 ± 11.79 | 62 ± 26.83 | 46.67 ± 24.72 | ||

| GATv2 | None | TRUE | 58.43 ± 13.32 | 56 ± 15.17 | 66.67 ± 42.49 |

| p = 0.2 | 42.44 ± 30.55 | 52 ± 46.04 | 60 ± 43.46 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 43.11 ± 26.84 | 48 ± 35.64 | 60 ± 43.46 | ||

| Min conn. | 65.22 ± 8.51 | 96 ± 8.94 | 23.33 | ||

| None | FALSE | 70.41 ± 18.16 | 79 ± 20.12 | 60 ± 41.83 | |

| p = 0.2 | 61.33 ± 14.05 | 69 ± 28.37 | 63.33 ± 21.73 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 53.5 ± 30.85 | 80 ± 44.72 | 33.33 ± 47.14 | ||

| Min conn. | 57.71 ± 11.77 | 73 ± 28.2 | 43.33 ± 40.14 | ||

| XGBoost | 66.55 ± 4.5 | 84 ± 16.73 | 50 ± 16.67 | ||

| Random Forest | 63.05 ± 8.14 | 96 ± 8.94 | 16.67 ± 23.57 | ||

| SVM | 61.19 ± 4.07 | 100 ± 0 | 3.33 ± 7.45 | ||

| Logistic regression | 69.97 ± 14.13 | 78 ± 17.89 | 63.33 ± 36.13 | ||

| Elastic net | 61.02 ± 13.79 | 78 ± 22.8 | 40 ± 34.56 |

| Model Type | Sparsity | Node feature | F1 | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | None | TRUE | 55.55 ± 31.92 | 76 ± 43.36 | 40 ± 36.51 |

| p = 0.2 | 47.37 ± 27.6 | 71 ± 41.29 | 20 ± 21.73 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 56.32 ± 13.78 | 74 ± 21.62 | 33.33 ± 26.35 | ||

| Min conn. | 51.6 ± 14.91 | 67 ± 32.71 | 36.67 ± 34.16 | ||

| None | FALSE | 61.27 ± 10.57 | 73 ± 19.24 | 50 ± 31.18 | |

| p = 0.2 | 63.56 ± 12.92 | 73 ± 13.04 | 56.67 ± 14.91 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 63.29 ± 11.18 | 85 ± 22.36 | 36.67 ± 24.72 | ||

| Min conn. | 48.48 ± 15.56 | 55 ± 20 | 46.67 ± 27.39 | ||

| GATv2 | None | TRUE | 33.71 ± 34 | 40 ± 46.9 | 70 ± 41.5 |

| p = 0.2 | 49.39 ± 30.35 | 58 ± 37.68 | 56.67 ± 34.56 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 48.5 ± 30.6 | 53 ± 40.56 | 60 ± 38.37 | ||

| Min conn. | 67.51 ± 8.45 | 87 ± 18.57 | 46.67 ± 24.72 | ||

| None | FALSE | 46.26 ± 20.74 | 58 ± 33.28 | 36.67 ± 21.73 | |

| p = 0.2 | 45.56 ± 27.33 | 54 ± 35.78 | 46.67 ± 24.72 | ||

| p = 0.8 | 42.78 ± 30 | 65 ± 48.73 | 26.67 ± 34.56 | ||

| Min conn. | 57.03 ± 32.75 | 72 ± 41.47 | 50 ± 23.57 | ||

| XGBoost | 46.46 ± 27.59 | 50 ± 31.42 | 70 ± 24.72 | ||

| Random Forest | 62.17 ± 8.57 | 96 ± 8.94 | 13.33 ± 21.73 | ||

| SVM | 61.19 ± 4.07 | 100 ± 0 | 3.33 ± 7.45 | ||

| Logistic regression | 39.05 ± 31.17 | 33 ± 26.36 | 80 ± 13.94 | ||

| Elastic net | 58.38 ± 19.77 | 59 ± 23.02 | 70 ± 13.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaikin, A.; Sviridov, I.; Oganezova, J.G.; Menon, U.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Timms, J.F.; Blyuss, O. Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243972

Zaikin A, Sviridov I, Oganezova JG, Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Timms JF, Blyuss O. Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243972

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaikin, Alexey, Ivan Sviridov, Janna G. Oganezova, Usha Menon, Aleksandra Gentry-Maharaj, John F. Timms, and Oleg Blyuss. 2025. "Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243972

APA StyleZaikin, A., Sviridov, I., Oganezova, J. G., Menon, U., Gentry-Maharaj, A., Timms, J. F., & Blyuss, O. (2025). Synolitic Graph Neural Networks of High-Dimensional Proteomic Data Enhance Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Cancers, 17(24), 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243972