Integrative Gene-Centric Analysis Reveals Cellular Pathways Associated with Heritable Breast Cancer Predisposition

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biobank Data Processing

2.2. GWAS, Coding-Gene GWAS and Summary Statistics Analyses

2.3. Gene-Level Effect Scores Across the Human Proteome

2.4. Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS) Analysis

2.5. External Comparative Analyses and Dependency Among Cohorts

2.6. Bioinformatics Tools

2.7. Resource and Availability

3. Results

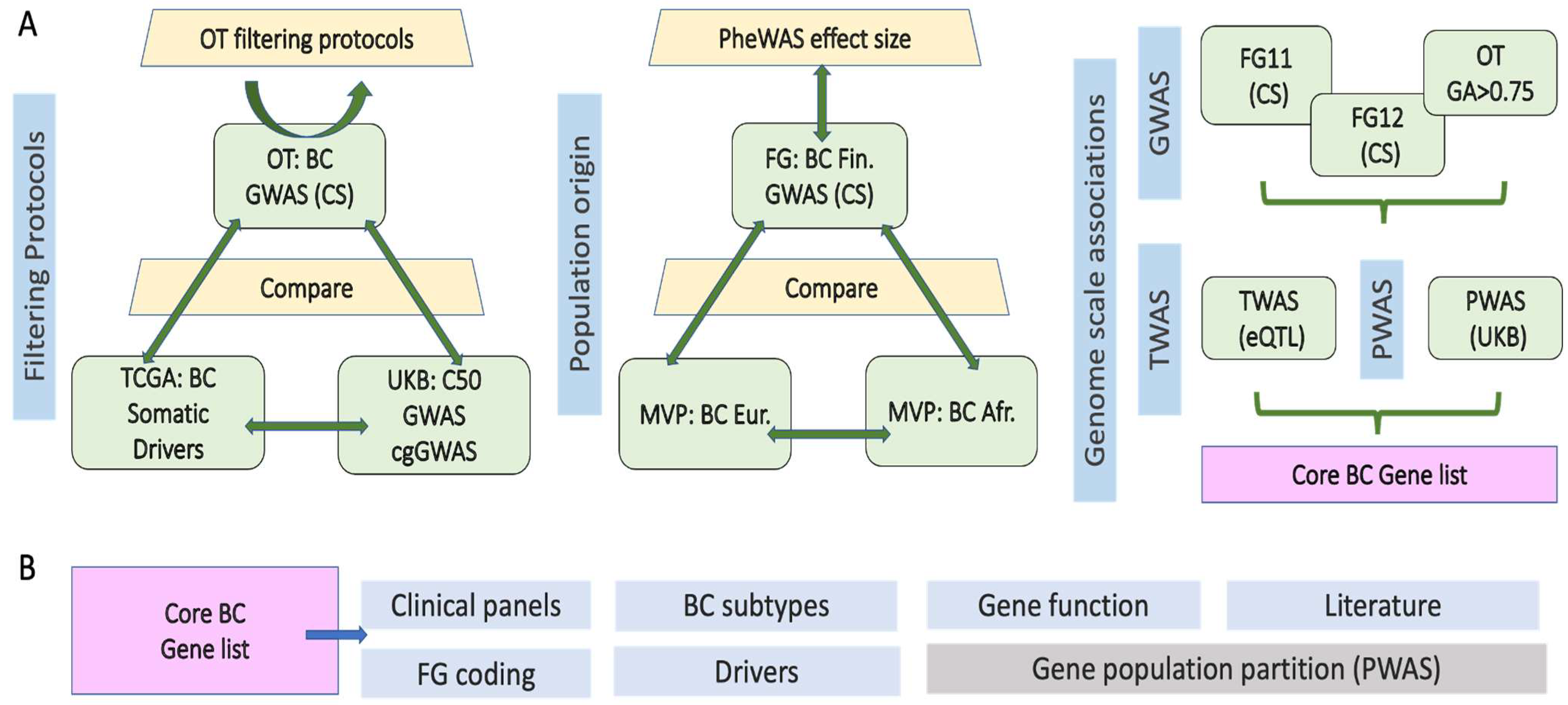

3.1. Integrative Framework for Breast Cancer (BC) Gene Identification and Validation

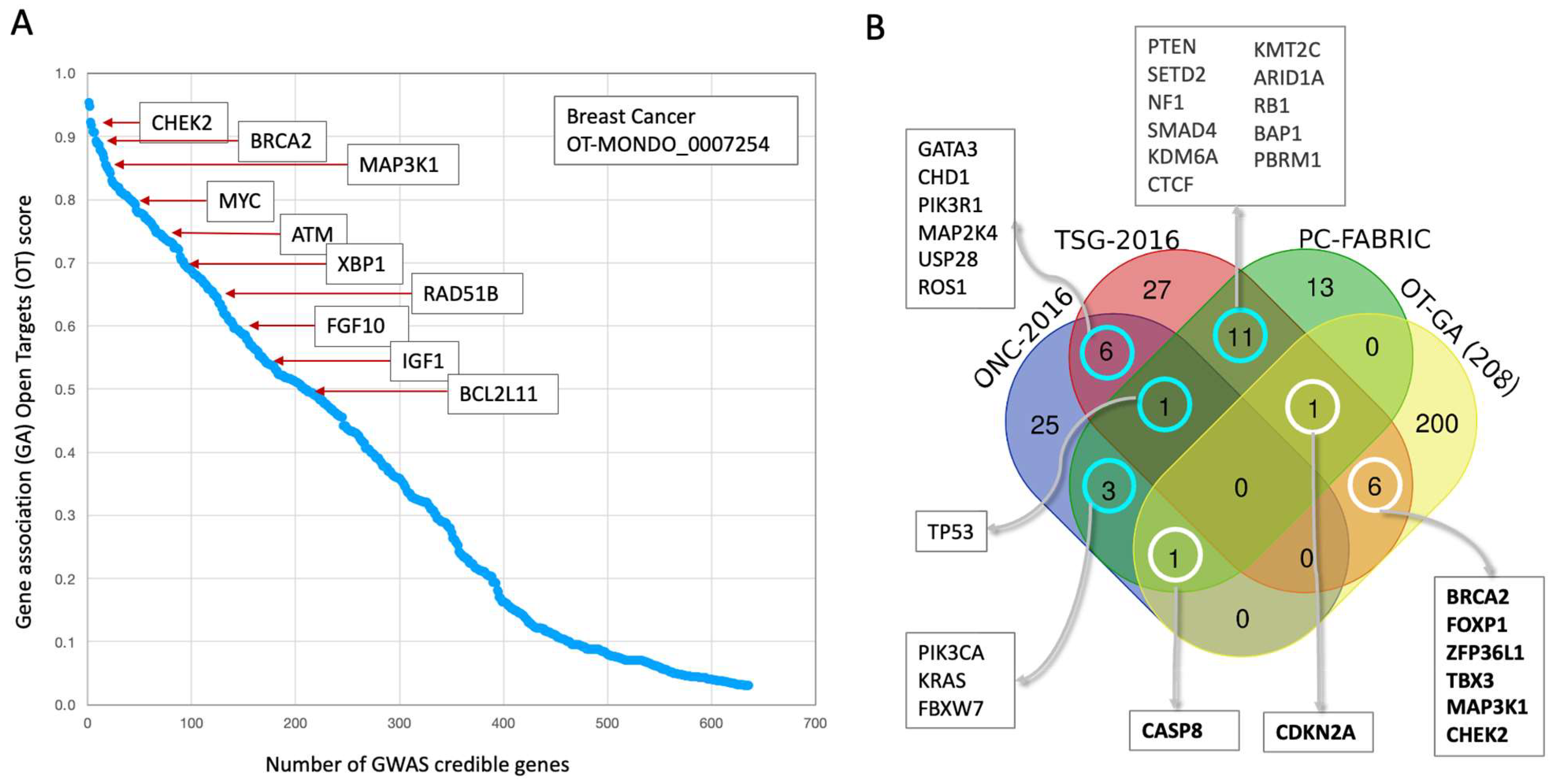

3.2. Germline Risk Genes for BC and Somatic Driver Genes Are Largely Distinct

3.3. Prioritizing Candidate Genes from the Abundance of GWAS False Positive Genes

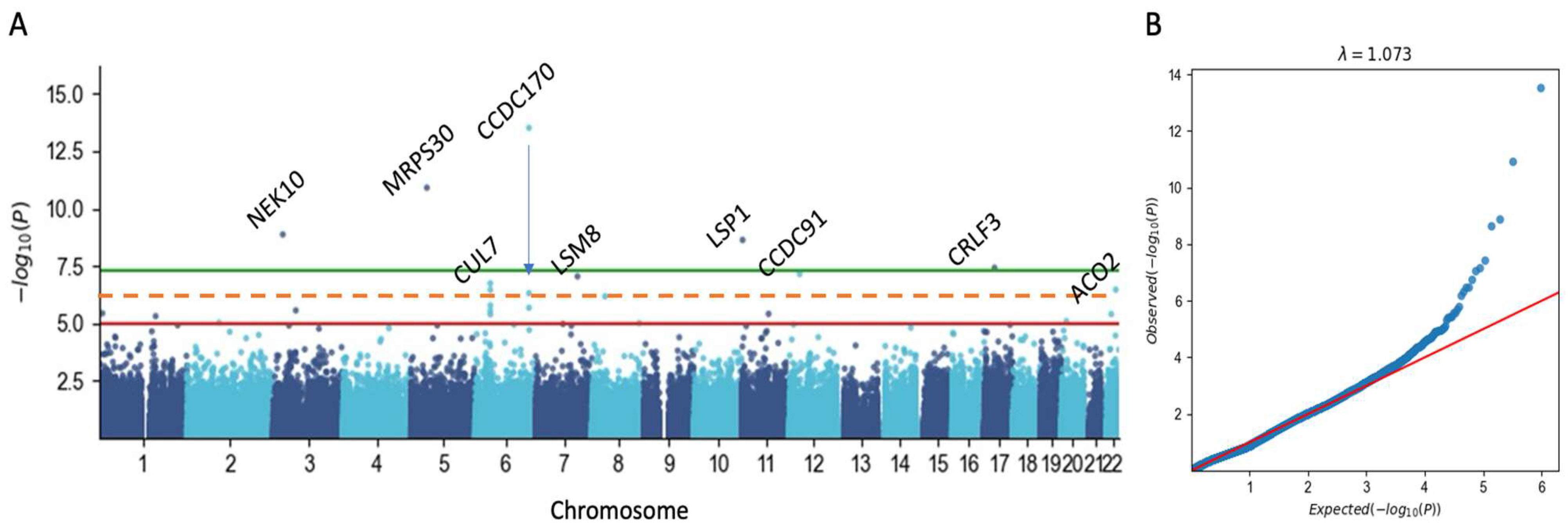

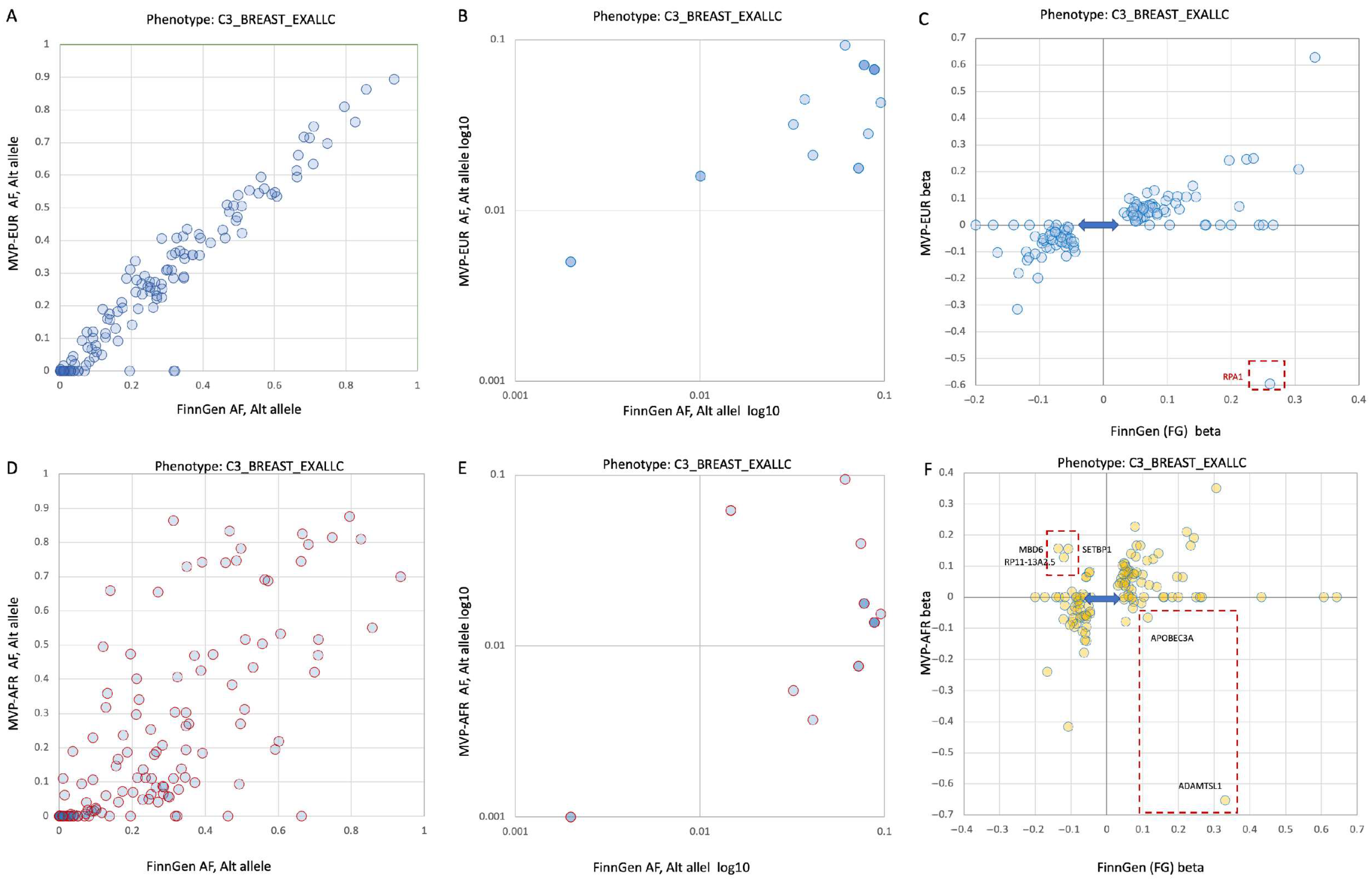

3.4. Germline Risk Genetics for BC Is Sensitive to Population Origin

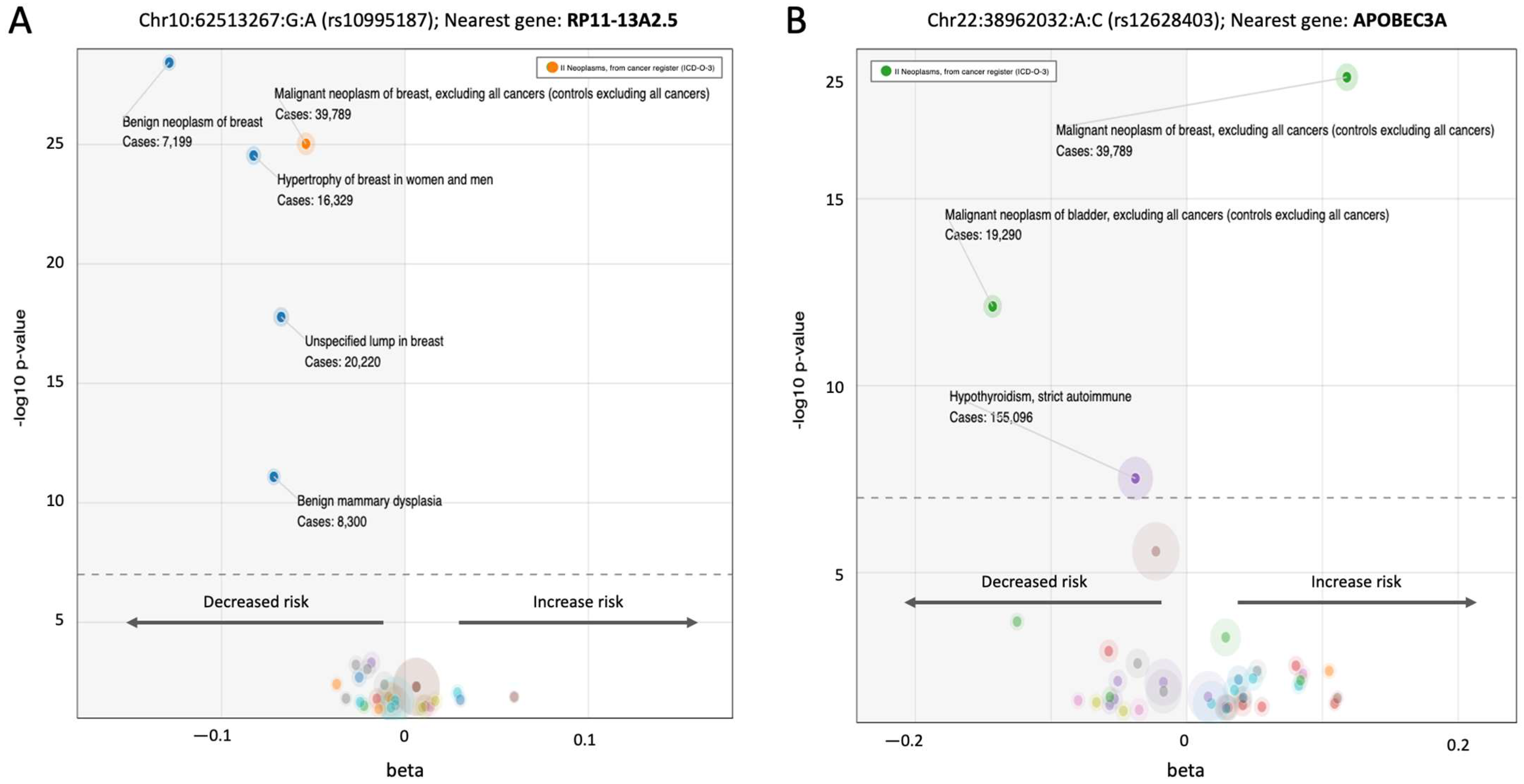

3.5. A Pleotropic Nature of BC Associated Variants with Moderate Effect Size

3.6. Gene-Based Functional Model of PWAS with Inheritance Mode

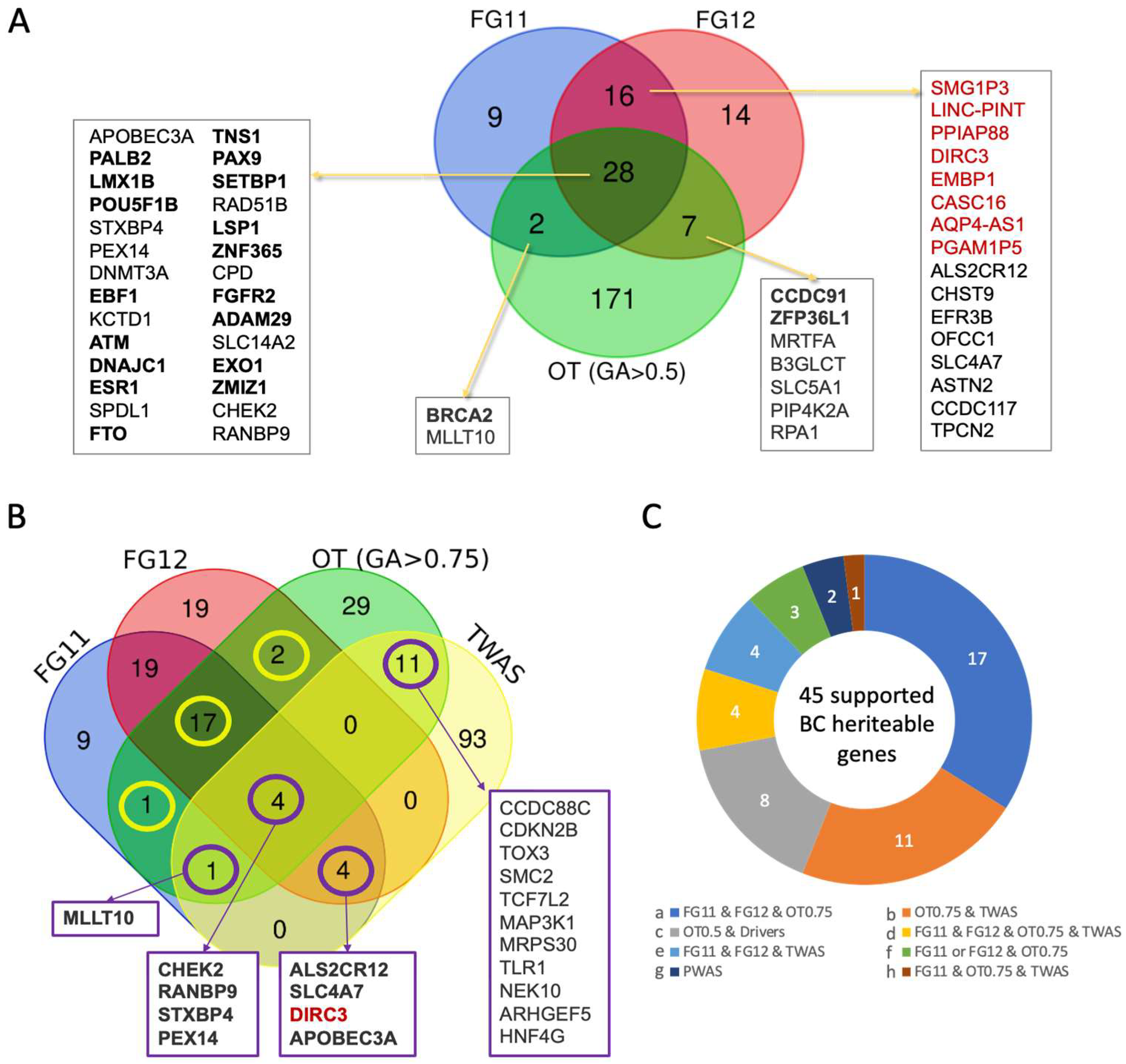

3.7. Robust BC Predisposition Gene List and Transcriptome-Based Associations

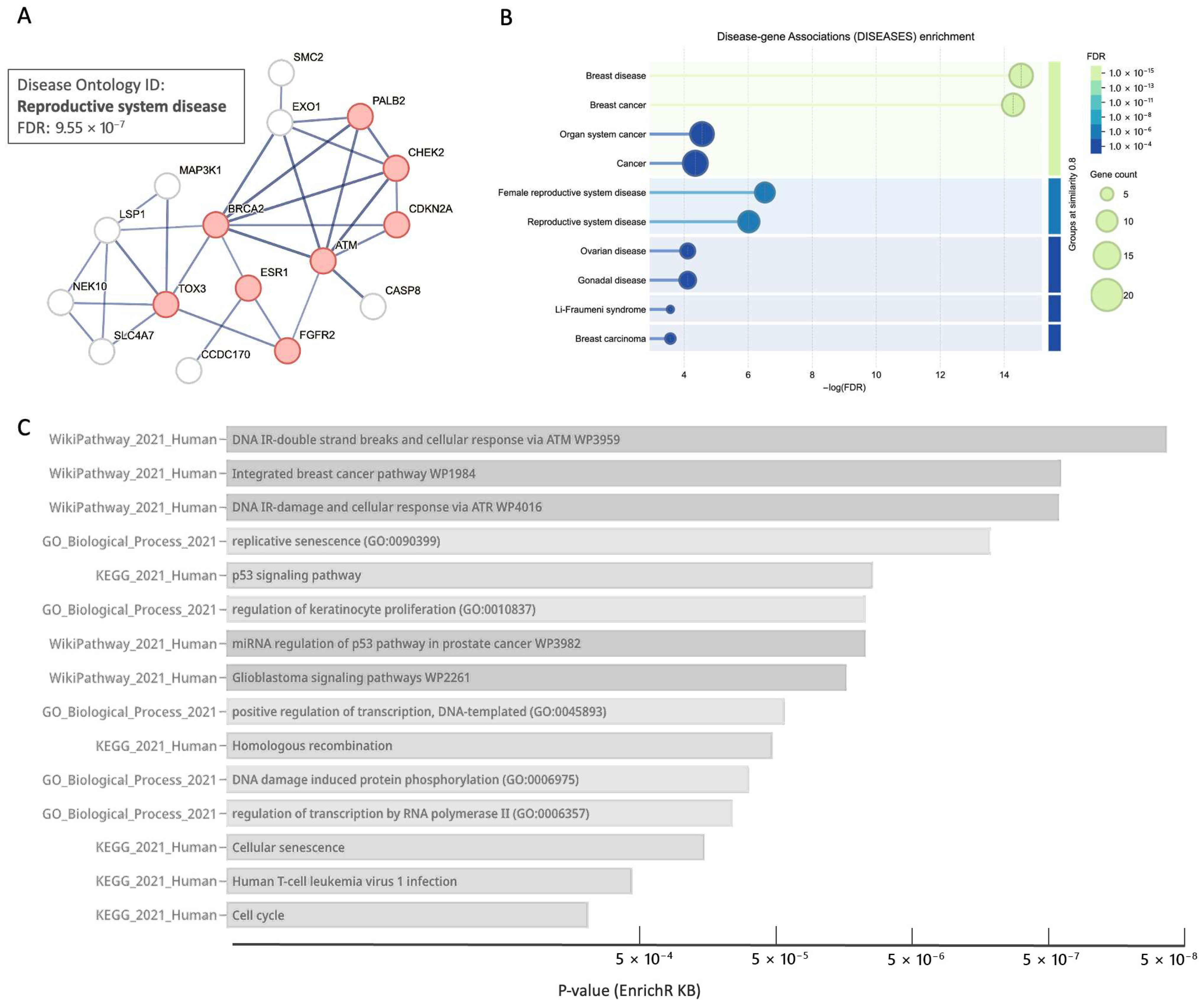

3.8. Core BC Predisposition Genes Are Highlight Processes of DNA Integrity and Stability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | breast cancer |

| CS | credible set |

| eQTL | expression quantitative trait locus |

| FG | FinnGen |

| GWAS | genome wide association study |

| ICD10 | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems,10th Revision |

| LD | linkage disequilibrium |

| LOF | loss of function |

| lncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| MAF | minor allele frequency |

| MVP | million veteran program |

| ONC | oncogene |

| OR | odds ratio |

| OT | open targets |

| PheWAS | phenome wide association study |

| PRS | polygenic risk score |

| PWAS | proteome wide association study |

| TSG | tumor suppressor gene |

| TWAS | transcriptome wide association study |

| UKB | UK biobank |

References

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Breast cancer: A review of risk factors and diagnosis. Medicine 2024, 103, e36905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarz, B.; Nowak, A.Z.; Romanowicz, H. Breast cancer—Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis and treatment (review of literature). Cancers 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momenimovahed, Z.; Salehiniya, H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2019, 11, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, K.; Stuckey, A. Breast cancer epidemiology and risk factors. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 59, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja, O.; Debald, M.; Yeghiazaryan, K.; Kuhn, W.; Pešta, M.; Costigliola, V.; Grech, G. Breast cancer epidemic in the early twenty-first century: Evaluation of risk factors, cumulative questionnaires and recommendations for preventive measures. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 12941–12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, D.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Zhu, W.; Demb, J.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Sprague, B.; Tice, J.A.; Onega, T.; Henderson, L.M.; Buist, D.S. Family history and breast cancer risk among older women in the breast cancer surveillance consortium cohort. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A.; Jian, J.-W.; Hung, C.-F.; Peng, H.-P.; Yang, C.-F.; Cheng, H.-C.S.; Yang, A.-S. Germline breast cancer susceptibility gene mutations and breast cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavaddat, N.; Antoniou, A.C.; Easton, D.F.; Garcia-Closas, M. Genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2010, 4, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, V.; Bucalo, A.; Conti, G.; Celli, L.; Porzio, V.; Capalbo, C.; Silvestri, V.; Ottini, L. Gender-specific genetic predisposition to breast cancer: BRCA genes and beyond. Cancers 2024, 16, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.; Hussain, S.A.; Ghori, Q.; Naeem, N.; Fazil, A.; Giri, S.; Sathian, B.; Mainali, P.; Al Tamimi, D.M. The spectrum of genetic mutations in breast cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, A.; Imoto, I.; Iwata, H. Functions of Breast Cancer Predisposition Genes: Implications for Clinical Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Polley, E.C.; Yadav, S.; Lilyquist, J.; Shimelis, H.; Na, J.; Hart, S.N.; Goldgar, D.E.; Shah, S.; Pesaran, T. The contribution of germline predisposition gene mutations to clinical subtypes of invasive breast cancer from a clinical genetic testing cohort. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas Ribeiro, A.A.; Junior, N.M.C.; Dos Santos, L.L. Systematic review of the molecular basis of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome in Brazil: The current scenario. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Zayas, M.; Garrido-Navas, C.; Garcia-Puche, J.L.; Barwell, J.; Pedrinaci, S.; Atienza, M.M.; Garcia-Linares, S.; de Haro-Munoz, T.; Lorente, J.A.; Serrano, M.J.; et al. Identification of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer germline variants in Granada (Spain): NGS perspective. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.; Chen, W.C.; Babb de Villiers, C.; Hyuck Lee, S.; Curtis, C.; Newton, R.; Waterboer, T.; Sitas, F.; Bradshaw, D.; Muchengeti, M. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants associated with breast cancer in South African Black women. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, F.J.; Shimelis, H.; Hu, C.; Hart, S.N.; Polley, E.C.; Na, J.; Hallberg, E.; Moore, R.; Thomas, A.; Lilyquist, J.; et al. Associations Between Cancer Predisposition Testing Panel Genes and Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.; Johnstone, K.; McCart Reed, A.; Simpson, P.; Lakhani, S. Hereditary breast cancer: Syndromes, tumour pathology and molecular testing. Histopathology 2023, 82, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolo, P.; Silvestri, V.; Falchetti, M.; Ottini, L. Inherited and acquired alterations in development of breast cancer. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2011, 4, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, N.; Widen, E.; Kerminen, S.; Meretoja, T.; Pirinen, M.; Della Briotta Parolo, P.; Palta, P.; FinnGen; Palotie, A.; Kaprio, J.; et al. The role of polygenic risk and susceptibility genes in breast cancer over the course of life. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Hughes, E.; Wagner, S.; Tshiaba, P.; Rosenthal, E.; Roa, B.B.; Kurian, A.W.; Domchek, S.M.; Garber, J.; Lancaster, J.; et al. Association of a Polygenic Risk Score with Breast Cancer Among Women Carriers of High- and Moderate-Risk Breast Cancer Genes. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e208501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, A.; Kampe, A.; Torngren, T.; Tesi, B.; Baliakas, P.; Borg, A.; Eriksson, D. Polygenic scores in Familial breast cancer cases with and without pathogenic variants and the risk of contralateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2025, 27, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurki, M.I.; Karjalainen, J.; Palta, P.; Sipilä, T.P.; Kristiansson, K.; Donner, K.; Reeve, M.P.; Laivuori, H.; Aavikko, M.; Kaunisto, M.A. FinnGen: Unique genetic insights from combining isolated population and national health register data. Nature 2023, 613, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuusisto, K.M.; Bebel, A.; Vihinen, M.; Schleutker, J.; Sallinen, S.-L. Screening for BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, BRIP1, RAD50, and CDH1 mutations in high-risk Finnish BRCA1/2-founder mutation-negative breast and/or ovarian cancer individuals. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Cho, D.Y.; Choi, D.H.; Oh, M.; Shin, I.; Park, W.; Huh, S.J.; Nam, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.W. Frequency of pathogenic germline mutation in CHEK2, PALB2, MRE11, and RAD50 in patients at high risk for hereditary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliovich, D.; Kaduri, L.; Lerer, I.; Weinberg, N.; Amir, G.; Sagi, M.; Zlotogora, J.; Heching, N.; Peretz, T. The founder mutations 185delAG and 5382insC in BRCA1 and 6174delT in BRCA2 appear in 60% of ovarian cancer and 30% of early-onset breast cancer patients among Ashkenazi women. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 60, 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal-Garza, C.; Alvarez-Gomez, R.M.; Perez-Plasencia, C.; Herrera, L.A.; Herzog, J.; Castillo, D.; Mohar, A.; Castro, C.; Gallardo, L.N.; Gallardo, D.; et al. Significant clinical impact of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Mexico. Cancer 2015, 121, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Lahad, E.; Catane, R.; Eisenberg, S.; Kaufman, B.; Hornreich, G.; Lishinsky, E.; Shohat, M.; Weber, B.L.; Beller, U.; Lahad, A.; et al. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel: Frequency and differential penetrance in ovarian cancer and in breast-ovarian cancer families. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 60, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Lolas Hamameh, S.; Renbaum, P.; Kamal, L.; Dweik, D.; Salahat, M.; Jaraysa, T.; Abu Rayyan, A.; Casadei, S.; Mandell, J.B.; Gulsuner, S.; et al. Genomic analysis of inherited breast cancer among Palestinian women: Genetic heterogeneity and a founder mutation in TP53. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.B.; Kurki, M.I.; Foley, C.N.; Mechakra, A.; Chen, C.Y.; Marshall, E.; Wilk, J.B.; Biogen Biobank, T.; Chahine, M.; Chevalier, P.; et al. Genetic associations of protein-coding variants in human disease. Nature 2022, 603, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, K.; Beesley, J.; Lindstrom, S.; Canisius, S.; Dennis, J.; Lush, M.J.; Maranian, M.J.; Bolla, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Shah, M.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Das, D.; Pandey, M. Understanding genetic variations associated with familial breast cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 22, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.C.; Michelli, R.A.; Galvão, H.C.; Paula, A.E.; Pereira, R.; Andrade, C.E.; Felicio, P.S.; Souza, C.P.; Mendes, D.R.; Volc, S. Prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in a Brazilian population sample at-risk for hereditary breast cancer and characterization of its genetic ancestry. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 80465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, T.; Song, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, J. From genetic associations to genes: Methods, applications, and challenges. Trends Genet. 2024, 40, 642–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, R.; Kelman, G.; Linial, M. PWAS Hub: Exploring gene-based associations of complex diseases with sex dependency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1132–D1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Gifford, A.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Campbell, H.; Varley, T.; Zhao, J.; Carroll, R.; Bastarache, L.; Denny, J.C.; et al. Mapping ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM Codes to Phecodes: Workflow Development and Initial Evaluation. JMIR Med. Inf. 2019, 7, e14325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, G.; Zucker, R.; Brandes, N.; Linial, M. PWAS Hub for exploring gene-based associations of common complex diseases. Genome Res. 2024, 34, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, N.; Linial, N.; Linial, M. PWAS: Proteome-wide association study—Linking genes and phenotypes by functional variation in proteins. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoussaini, M.; Mountjoy, E.; Carmona, M.; Peat, G.; Schmidt, E.M.; Hercules, A.; Fumis, L.; Miranda, A.; Carvalho-Silva, D.; Buniello, A. Open Targets Genetics: Systematic identification of trait-associated genes using large-scale genetics and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1311–D1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, N.; Linial, N.; Linial, M. Genetic association studies of alterations in protein function expose recessive effects on cancer predisposition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, E.; Margaliot, I.; Brandes, N.; Zuk, O.; Linial, M.; Rappoport, N. Selecting covariates for genome-wide association studies. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.G.; Kim, R.S.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.Y.-L.; Leow, S.M.H.; Bea, K.T.; Cheng, W.K.; Phoong, S.W.; Hong, Z.-W.; Chen, Y.-L. Mitigating the multicollinearity problem and its machine learning approach: A review. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.M. Genetic susceptibility to breast cancer in lymphoma survivors. Blood 2019, 133, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legault, M.-A.; Perreault, L.-P.L.; Tardif, J.-C.; Dubé, M.-P. ExPheWas: A platform for cis-Mendelian randomization and gene-based association scans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W305–W311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, G.; Tanigawa, Y.; DeBoever, C.; Lavertu, A.; Olivieri, J.E.; Aguirre, M.; Rivas, M.A. Global Biobank Engine: Enabling genotype-phenotype browsing for biobank summary statistics. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2495–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Umićević Mirkov, M.; de Leeuw, C.A.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Posthuma, D. Genetic mapping of cell type specificity for complex traits. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P. STRING v10: Protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, J.E.; Xie, Z.; Marino, G.B.; Nguyen, N.; Clarke, D.J.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr-KG: Bridging enrichment analysis across multiple libraries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W168–W179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, N.; Linial, N.; Linial, M. Quantifying gene selection in cancer through protein functional alteration bias. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6642–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Dunning, A.M.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Balasubramanian, S.; Reed, M.W.; Pooley, K.A.; Scollen, S.; Baynes, C.; Ponder, B.A.; Chanock, S.; et al. A common coding variant in CASP8 is associated with breast cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Economopoulos, K.P. Association of two CASP8 polymorphisms with breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 120, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potrony, M.; Puig-Butille, J.A.; Farnham, J.M.; Giménez-Xavier, P.; Badenas, C.; Tell-Martí, G.; Aguilera, P.; Carrera, C.; Malvehy, J.; Teerlink, C.C. Genome-wide linkage analysis in Spanish melanoma-prone families identifies a new familial melanoma susceptibility locus at 11q. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passi, G.; Lieberman, S.; Zahdeh, F.; Murik, O.; Renbaum, P.; Beeri, R.; Linial, M.; May, D.; Levy-Lahad, E.; Schneidman-Duhovny, D. Discovering predisposing genes for hereditary breast cancer using deep learning. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeraraghavan, J.; Tan, Y.; Cao, X.-X.; Kim, J.A.; Wang, X.; Chamness, G.C.; Maiti, S.N.; Cooper, L.J.; Edwards, D.P.; Contreras, A. Recurrent ESR1–CCDC170 rearrangements in an aggressive subset of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.C.; Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Soucy, P.; Beesley, J.; Chen, X.; McGuffog, L.; Lee, A.; Barrowdale, D.; Healey, S.; Sinilnikova, O.M. Common variants at 12p11, 12q24, 9p21, 9q31. 2 and in ZNF365 are associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, F.J.; Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Michailidou, K.; Mendoza-Fandino, G.A.; Nord, S.; Lilyquist, J.; Olswold, C.; Hallberg, E.; Agata, S.; Ahsan, H.; et al. Identification of four novel susceptibility loci for oestrogen receptor negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, T.U.; Zhang, H.; Michailidou, K.; Milne, R.L.; Bolla, M.K.; Dennis, J.; Dunning, A.M.; Lush, M.; Wang, Q.; Andrulis, I.L.; et al. Common variants in breast cancer risk loci predispose to distinct tumor subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann, E.; Huang, Q.Q.; Munung, N.S.; De Vries, J.; Okada, Y.; Martin, A.R.; Martin, H.C.; Lappalainen, T.; Posthuma, D. Genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Elzur, R.A.; Kanai, M.; Ulirsch, J.C.; Weissbrod, O.; Daly, M.J.; Neale, B.M.; Fan, Z.; Finucane, H.K. Improving fine-mapping by modeling infinitesimal effects. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, D.; Amos, C.I. False positive findings during genome-wide association studies with imputation: Influence of allele frequency and imputation accuracy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 31, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, N.; Weissbrod, O.; Linial, M. Open problems in human trait genetics. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Gamez, E.; Trynka, G. From GWAS to function: Using functional genomics to identify the mechanisms underlying complex diseases. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderle, M.; Olmes, G.; Nabieva, N.; Haberle, L.; Jud, S.M.; Hein, A.; Rauh, C.; Hack, C.C.; Erber, R.; Ekici, A.B.; et al. Risk, Prediction and Prevention of Hereditary Breast Cancer - Large-Scale Genomic Studies in Times of Big and Smart Data. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2018, 78, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bakker, P.I.; Ferreira, M.A.; Jia, X.; Neale, B.M.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Voight, B.F. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, R122–R128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, R.; Kovalerchik, M.; Stern, A.; Kaufman, H.; Linial, M. Revealing the genetic complexity of hypothyroidism: Integrating complementary association methods. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1409226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petmezas, G.; Papageorgiou, V.E.; Vassilikos, V.; Pagourelias, E.; Tachmatzidis, D.; Tsaklidis, G.; Katsaggelos, A.K.; Maglaveras, N. Enhanced heart failure mortality prediction through model-independent hybrid feature selection and explainable machine learning. J. Biomed. Inf. 2025, 163, 104800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, G.J.; Rizzo, M.L.; Bakirov, N.K. Measuring and testing dependence by correlation of distances. Ann. Stat. 2007, 35, 2769–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Middha Kapoor, P.; Su, Y.R.; Bolla, M.K.; Dennis, J.; Dunning, A.M.; Lush, M.; Wang, Q.; Michailidou, K.; et al. A genome-wide gene-based gene-environment interaction study of breast cancer in more than 90,000 women. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiovitz, S.; Korde, L.A. Genetics of breast cancer: A topic in evolution. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 2020, 578, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Association, C.; Dorling, L.; Carvalho, S.; Allen, J.; Gonzalez-Neira, A.; Luccarini, C.; Wahlstrom, C.; Pooley, K.A.; Parsons, M.T.; Fortuno, C.; et al. Breast Cancer Risk Genes—Association Analysis in More than 113,000 Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Hart, S.N.; Gnanaolivu, R.; Huang, H.; Lee, K.Y.; Na, J.; Gao, C.; Lilyquist, J.; Yadav, S.; Boddicker, N.J.; et al. A Population-Based Study of Genes Previously Implicated in Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Park, S.L.; Wilkens, L.R.; Wan, P.; Hart, S.N.; Hu, C.; Yadav, S.; Couch, F.J.; Conti, D.V.; de Smith, A.J.; et al. Genetic Risk of Second Primary Cancer in Breast Cancer Survivors: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, A.; Sami, A.; Dixon, J. Breast cancer risk among the survivors of atomic bomb and patients exposed to therapeutic ionising radiation. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2003, 29, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Rowley, S.M.; Thompson, E.R.; McInerny, S.; Devereux, L.; Amarasinghe, K.C.; Zethoven, M.; Lupat, R.; Goode, D.; Li, J.; et al. Evaluating the breast cancer predisposition role of rare variants in genes associated with low-penetrance breast cancer risk SNPs. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, N.; Dumont, M.; Gonzalez-Neira, A.; Carvalho, S.; Joly Beauparlant, C.; Crotti, M.; Luccarini, C.; Soucy, P.; Dubois, S.; Nunez-Torres, R.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies breast cancer susceptibility genes and defines the contribution of coding variants to breast cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, C.; Carrot-Zhang, J.; Kluzniak, W.; Rivera, B.; Kashyap, A.; Wokolorczyk, D.; Giroux, S.; Nadaf, J.; Hamel, N.; Zhang, S.; et al. Germline RECQL mutations are associated with breast cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasnic, R.; Linial, N.; Linial, M. Expanding cancer predisposition genes with ultra-rare cancer-exclusive human variations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavaddat, N.; Michailidou, K.; Dennis, J.; Lush, M.; Fachal, L.; Lee, A.; Tyrer, J.P.; Chen, T.-H.; Wang, Q.; Bolla, M.K. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.M.; Hofmeister, R.J.; Rubinacci, S.; Delaneau, O. Noncoding rare variant associations with blood traits in 166,740 UK Biobank genomes. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 2146–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvanto, M.; Beesley, J.; Blomqvist, C.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; Khan, S.; Nevanlinna, H. SNPs in lncRNA regions and breast cancer risk. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Main Feature/Function | Relevance to BC Predisposition | Role, [Penet.] a | Population b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCNE1 | Cell cycle: G1–S transition | Amplified in aggressive BC | BC driver | No |

| C11orf65 | Mitochondrial-related gene | ? | ? | No |

| PTPN11 | Phosphatase in RAS/MAPK signaling | Somatic mutations in BC tumors | ? | No |

| RAD51B | DNA repair, homologous recombination | Low-penetrance gene | [Low] | European and Asian |

| BRCA2 | DNA repair, homologous recombination | Strong association, hereditary BC | [High] | Ashkenazi Jews, Icelandic, French Canadian |

| DNMT3A | DNA methylation, epigenetic regulation | Common in blood cancers | ? | No |

| ATM | DNA damage response; cell cycle checkpoints | Moderate-risk gene | [High-Mod] | European |

| ERBB4 | EGFR family TK receptor | ? | ? | No |

| PALB2 | BRCA2 binding partner; DNA repair | Strongly linked to hereditary BC | [High-Mod] | Finnish, French Canadian, Polish |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor; hormone signaling | Common in ER-positive BC | BC driver | No |

| GeneSet | N (n) a | Adj. p-Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 184 (16) | 1.85 × 10−25 | PEX14, WDR43, DLX2, CDCA7, NEK10, MRPS30, CCDC170, LMX1B, DNAJC1, ZNF365, ZMIZ1, FAR2, PAX9, CCDC88C, TOX3, FTO |

| BC (ER−) | 25 (5) | 6.98 × 10−8 | PEX14, WDR43, ZNF365, TOX3, FTO |

| Breast size | 59 (5) | 4.29 × 10−6 | PEX14, CCDC170, ZNF365, CCDC91, FTO |

| BC | 17 (3) | 6.31 × 10−4 | DNAJC1, CCDC88C, STXBP4 |

| Gene Symbol | Shared Evidence a | FG Coding #Var (V), #Ph b | FG CS c ER+, ER− | Shared Driver d | Clinial Panel e | BC Predisp. Literature f | Broad Functional Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAM29 | a | - | ER+ | - | No | Proteolysis/Cell adhesion | |

| ALS2CR12 | e | V1, Ph1 | ER− | - | No | Cell projection | |

| APOBEC3A | e | - | ER+ | - | No | DNA/RNA editing | |

| ARHGEF5 * | b | - | - | No | Rho GTPase signaling | ||

| ATM | a | V1, Ph2 | ER+ | - | I, M | Yes | DNA damage repair |

| BRCA2 | c,f | V2, Ph2 | ER+ | TSG | I, M | Yes | DNA repair (homologous recombination) |

| CASP8 | c | V1, Ph2 | ONC | Yes | Apoptosis regulation | ||

| CCDC170 | g,i | V2, Ph6 | - | Yes | Structural protein (CC domain) | ||

| CCDC88C * | b | - | - | No | Cell migration signaling | ||

| CCDC91 | f | - | - | No | Vesicle trafficking | ||

| CDKN2A | c | - | TSG | Yes | Cell cycle control | ||

| CDKN2B * | b | - | - | No | Cell cycle control | ||

| CHEK2 | c,d,g | V3, Ph3 | Shared | TGS | I, M | Yes | DNA damage checkpoint |

| DIRC3 | e | - | ER+ | - | Yes | Non-coding RNA regulator | |

| DNAJC1 | a | - | ER+ | - | No | Protein folding (HSP40 chaperone) | |

| EBF1 | a | - | - | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| ESR1 | a,i | - | ER+ | - | Yes | Nuclear hormone receptor | |

| EXO1 | a | V1, Ph2 | ER+ | - | Yes# | DNA repair/recombination | |

| FGFR2 | a,i | - | Shared | - | Yes | Receptor tyrosine kinase/Signaling | |

| FOXP1 | c | - | TSG | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| FTO | a | - | Shared | - | No | RNA demethylase/Epigenetics | |

| HNF4G * | b | - | - | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| LMX1B | a | - | - | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| LSP1 | a,g | V3, Ph3 | ER+ | - | Yes | Actin cytoskeleton regulation | |

| MAP3K1 | b,c,i | V1, Ph2 | TGS | Yes | MAPK signaling pathway | ||

| MLLT10 | h | - | - | No | Chromatin remodeling/Transcription | ||

| MRPS30 | b,g,i | V1, Ph4 | - | No | Mitochondrial translation | ||

| NEK10 | b,g,i | V2, Ph2 | - | Yes | Cell cycle kinase | ||

| PAX9 | a,i | - | ER+ | - | No | Transcription regulation | |

| PALB2 | a | V1, Ph3 | Shared | - | I, M | Yes | DNA repair (homologous recombination) |

| PEX14 | d | - | - | No | Peroxisomal membrane transport | ||

| POU5F1B | a | V1, Ph2 | ER+ | - | No | Transcription regulation | |

| RANBP9 | d | - | ER+ | - | No | Protein scaffolding | |

| SETBP1 | a | - | - | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| SLC4A7 | e,i | - | ER+ | - | Yes | Ion transport | |

| SMC2 * | b | - | - | No | Chromosome condensation | ||

| STXBP4 | d | V2, Ph2 | - | No | Vesicular transport | ||

| TBX3 | c | - | TSG | Yes | Transcription regulation | ||

| TCF7L2 * | b | - | - | No | Transcription regulation | ||

| TLR1 * | b | - | - | No | Innate immune receptor | ||

| TNS1 | a | - | - | No | Focal adhesion signaling | ||

| TOX3 | b,i | - | ER− | - | Yes | Transcription regulation | |

| ZFP36L1 | c,f | - | TSG | No | mRNA decay/Post-transcription | ||

| ZMIZ1 | a | - | ER+ | - | Yes | Transcription coactivation | |

| ZNF365 | a | V1, Ph2 | Shared | - | Yes | Transcription/DNA repair |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zucker, R.; Schreiber, S.; Stern, A.; Linial, M. Integrative Gene-Centric Analysis Reveals Cellular Pathways Associated with Heritable Breast Cancer Predisposition. Cancers 2025, 17, 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243969

Zucker R, Schreiber S, Stern A, Linial M. Integrative Gene-Centric Analysis Reveals Cellular Pathways Associated with Heritable Breast Cancer Predisposition. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243969

Chicago/Turabian StyleZucker, Roei, Shirel Schreiber, Amos Stern, and Michal Linial. 2025. "Integrative Gene-Centric Analysis Reveals Cellular Pathways Associated with Heritable Breast Cancer Predisposition" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243969

APA StyleZucker, R., Schreiber, S., Stern, A., & Linial, M. (2025). Integrative Gene-Centric Analysis Reveals Cellular Pathways Associated with Heritable Breast Cancer Predisposition. Cancers, 17(24), 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243969