A Patient-Derived Organoid Platform from TUR-P Samples Enables Precision Drug Screening in Advanced Prostate Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection and Obtainment of Informed Consent

2.2. Patient-Derived Specimen Collection and Handling

2.3. Establishing Organoids from Advanced Prostate Cancer Specimens

2.4. Histology and Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.5. Short Tandem Repeat (STR) and Digital Droplet PCR

2.6. Whole-Exome Sequencing for the Genetic Profile Comparison of Tissue and Organoids

2.7. In Vitro Drug Screening

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

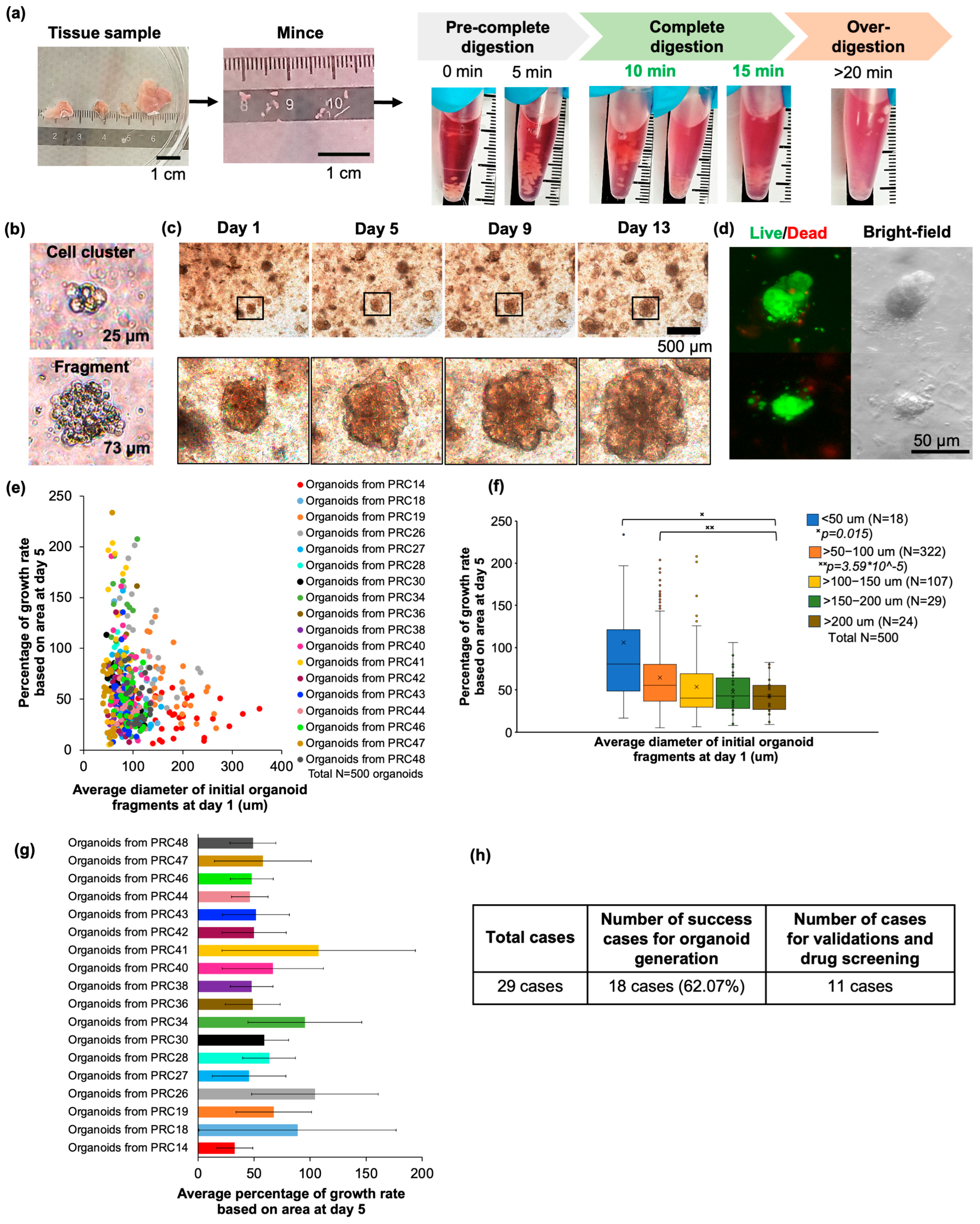

3.1. Improving the Protocol for Establishing Advanced Prostate Cancer Organoids

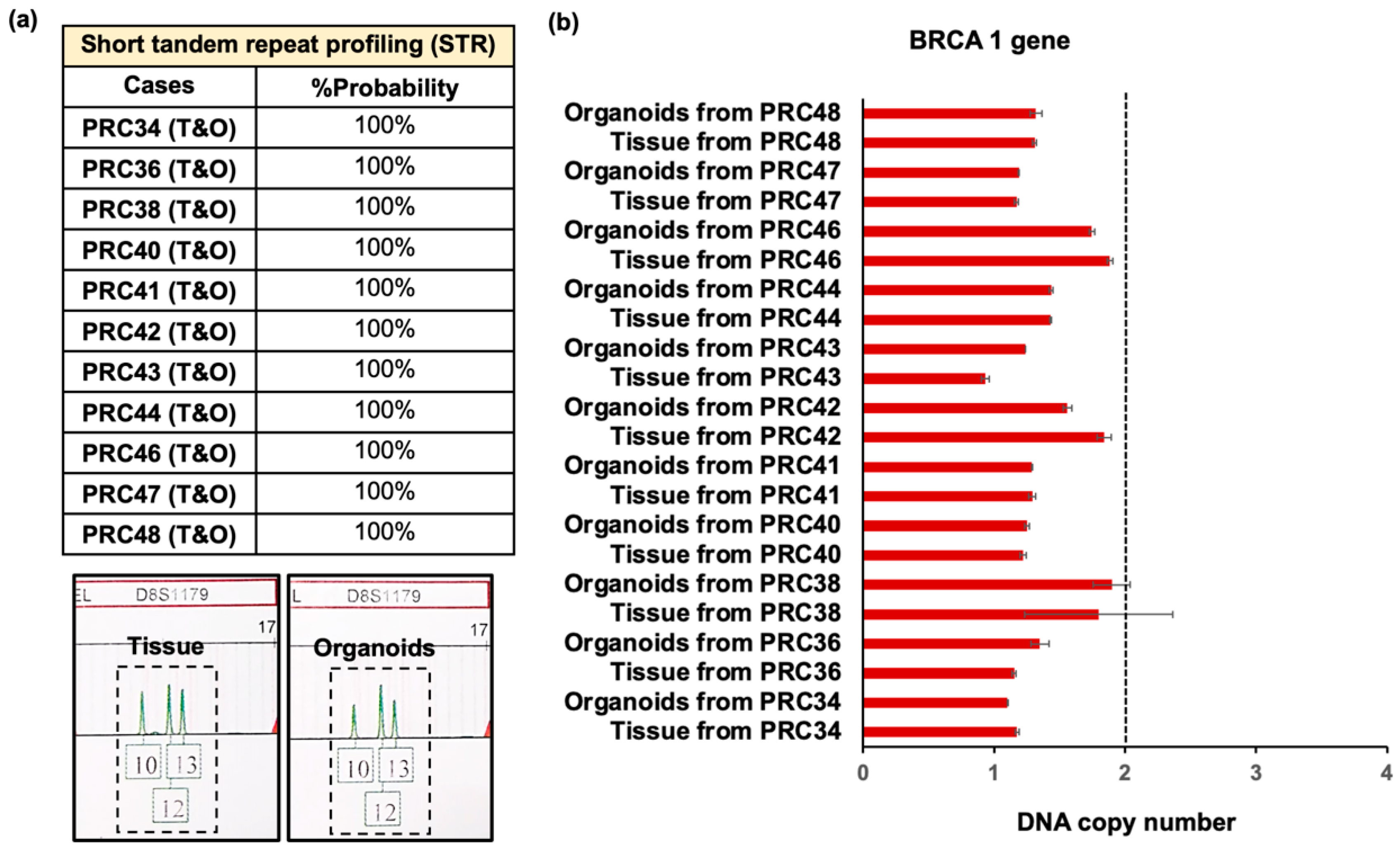

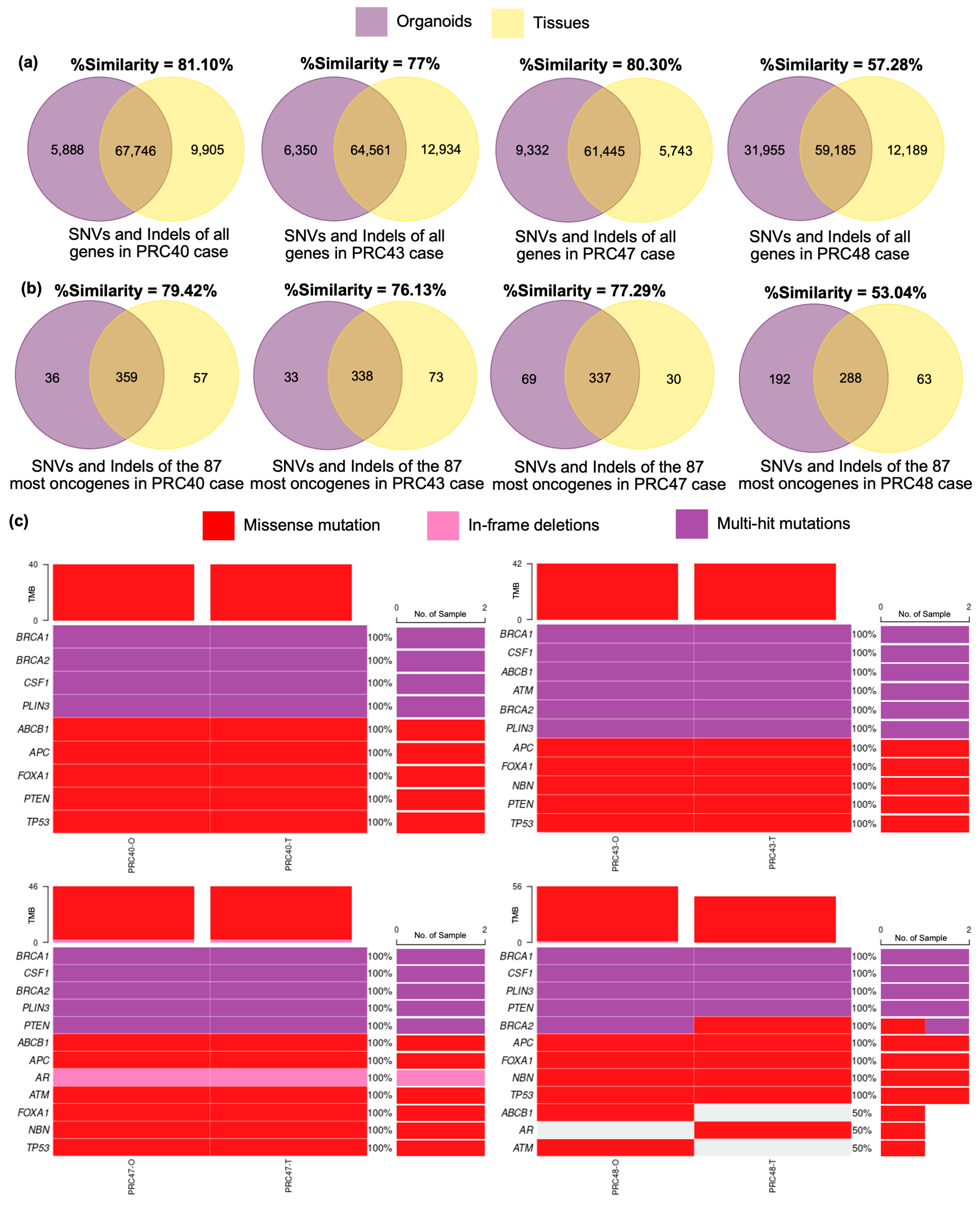

3.2. Validation of Advanced Prostate Cancer Organoids Compared with Original Tumors

3.3. Drug Screening Applications of Advanced Prostate Cancer Organoids

3.4. Correlation of In Vitro Drug Screening with Clinical Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.M. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Prostate Cancer); National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeh, B.; Würnschimmel, C.; Flammia, R.S.; Horlemann, B.; Sorce, G.; Chierigo, F.; Tian, Z.; Saad, F.; Graefen, M.; Gallucci, M.; et al. Effect of Chemotherapy on Overall Survival in Contemporary Metastatic Prostate Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 778858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, J.; McKay, R.; Abida, W.; Aggarwal, R.; Alumkal, J.; Alva, A.; Feng, F.; Gao, X.; Graff, J.; Hussain, M.; et al. Accelerating precision medicine in metastatic prostate cancer. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TCGA. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevedomskaya, E.; Baumgart, S.J.; Haendler, B. Recent Advances in Prostate Cancer Treatment and Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namekawa, T.; Ikeda, K.; Horie-Inoue, K.; Inoue, S. Application of Prostate Cancer Models for Preclinical Study: Advantages and Limitations of Cell Lines, Patient-Derived Xenografts, and Three-Dimensional Culture of Patient-Derived Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, F.; Raimondi, M.; Marzagalli, M.; Sommariva, M.; Gagliano, N.; Limonta, P. Three-Dimensional Cell Cultures as an In Vitro Tool for Prostate Cancer Modeling and Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkampouna, S.; La Manna, F.; Benjak, A.; Kiener, M.; De Menna, M.; Zoni, E.; Grosjean, J.; Klima, I.; Garofoli, A.; Bolis, M.; et al. Patient-derived xenografts and organoids model therapy response in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risbridger, G.P.; Clark, A.K.; Porter, L.H.; Toivanen, R.; Bakshi, A.; Lister, N.L.; Pook, D.; Pezaro, C.J.; Sandhu, S.; Keerthikumar, S.; et al. The MURAL collection of prostate cancer patient-derived xenografts enables discovery through preclinical models of uro-oncology. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant, R.; Garioni, M.; Vlajnic, T.; Blind, M.; Pueschel, H.; Müller, D.C.; Zellweger, T.; Templeton, A.J.; Garofoli, A.; Maletti, S.; et al. Prostate cancer patient-derived organoids: Detailed outcome from a prospective cohort of 81 clinical specimens. J. Pathol. 2021, 254, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puca, L.; Bareja, R.; Prandi, D.; Shaw, R.; Benelli, M.; Karthaus, W.R.; Hess, J.; Sigouros, M.; Donoghue, A.; Kossai, M.; et al. Patient derived organoids to model rare prostate cancer phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Vela, I.; Sboner, A.; Iaquinta, P.J.; Karthaus, W.R.; Gopalan, A.; Dowling, C.; Wanjala, J.N.; Undvall, E.A.; Arora, V.K.; et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2014, 159, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheaito, K.; Bahmad, H.F.; Hadadeh, O.; Msheik, H.; Monzer, A.; Ballout, F.; Dagher, C.; Telvizian, T.; Saheb, N.; Tawil, A.; et al. Establishment and characterization of prostate organoids from treatment-naïve patients with prostate cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, J.; Karthaus, W.R.; Gao, D.; Driehuis, E.; Sawyers, C.L.; Chen, Y.; Clevers, H. Organoid culture systems for prostate epithelial and cancer tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Mendoza, T.R.; Burner, D.N.; Muldong, M.T.; Wu, C.C.N.; Arreola-Villanueva, C.; Zuniga, A.; Greenburg, O.; Zhu, W.Y.; Murtadha, J.; et al. Novel Dormancy Mechanism of Castration Resistance in Bone Metastatic Prostate Cancer Organoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Maskey, N.; Yang, F.; Zheng, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, R.; Wu, P.; Mao, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Urological cancer organoids, patients’ avatars for precision medicine: Past, present and future. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthaus, W.R.; Iaquinta, P.J.; Drost, J.; Gracanin, A.; van Boxtel, R.; Wongvipat, J.; Dowling, C.M.; Gao, D.; Begthel, H.; Sachs, N.; et al. Identification of Multipotent Luminal Progenitor Cells in Human Prostate Organoid Cultures. Cell 2014, 159, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgelm, A.E.; Bergdorf, K.; Wolf, M.; Bharti, V.; Shattuck-Brandt, R.; Blevins, A.; Jones, C.; Phifer, C.; Lee, M.; Lowe, C.; et al. Fine-Needle Aspiration-Based Patient-Derived Cancer Organoids. iScience 2020, 23, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.-C.; Ibtisham, F.; Fayaz, M.A.; Honaramooz, A. Generation of a Highly Biomimetic Organoid, Including Vasculature, Resembling the Native Immature Testis Tissue. Cells 2021, 10, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.M.; Kannan, M.; Langer, L.F.; Leibowitz, B.D.; Bentaieb, A.; Cancino, A.; Dolgalev, I.; Drummond, B.E.; Dry, J.R.; Ho, C.-S.; et al. A pan-cancer organoid platform for precision medicine. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, Z.; Peroutka-Bigus, N.; Bellaire, B.; Jergens, A.; Wannemuehler, M.; Wang, Q. Gut Organoid as a New Platform to Study Alginate and Chitosan Mediated PLGA Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwarycz, B.; Gracz, A.D.; Rivera, K.R.; Williamson, I.A.; Samsa, L.A.; Starmer, J.; Daniele, M.A.; Salter-Cid, L.; Zhao, Q.; Magness, S.T. IL22 Inhibits Epithelial Stem Cell Expansion in an Ileal Organoid Model. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.I.E. Biostatistics for Medical and Biomedical Practitioners; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Sui, X.; Song, F.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Lung cancer organoids analyzed on microwell arrays predict drug responses of patients within a week. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Shao, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, K.; Tang, Q.; Xie, J. Genetic analysis of tri-allelic patterns at the CODIS STR loci. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2020, 295, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtcheva, N.; Nguyen-Sträuli, B.D.; Wagner, U.; Freiberger, S.N.; Varga, Z.; Britschgi, C.; Dedes, K.J.; Rechsteiner, M.P. Setting a diagnostic benchmark for tumor BRCA testing: Detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 large genomic rearrangements in FFPE tissue—A pilot study. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2021, 123, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscorbin, I.; Kechin, A.; Boyarskikh, U.; Filipenko, M. Multiplex ddPCR assay for screening copy number variations in BRCA1 gene. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 178, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungkamoltip, P.; Khongcharoen, N.; Nokchan, N.; Bostan Ali, Z.; Plikomol, M.; Bejrananda, T.; Boonchai, S.; Chamnina, S.; Srakhao, W.; Khongkow, P. Droplet Digital PCR Improves Detection of BRCA1/2 Copy Number Variants in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Zheng, T.; Wang, A.; Roacho, J.; Thao, S.; Du, P.; Jia, S.; Yu, J.; King, B.L.; Kohli, M. Dynamic changes in gene alterations during chemotherapy in metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhao, T.; Dong, B.; Chen, W.; Yang, G.; Xie, J.; Guo, C.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA and tissue complementarily detect genomic alterations in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. iScience 2024, 27, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Y.; Ding, L.; Zhou, T.R.; Yan, T.; Li, J.; Liang, C. FOXA1 in prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 2023, 25, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Johnson, N.; Cooke, L.; Johnson, B.; Chen, Y.; Pandey, M.; Chandler, J.; Mahadevan, D. TP53 Mutations as a Driver of Metastasis Signaling in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, Z.B.; Henderson, N.C.; Park, J.J.; Ali, A.; Nguyen, C.; Hwang, C.; Barata, P.C.; Bilen, M.A.; Graham, L.; Mo, G.; et al. Clinical implications of AR alterations in advanced prostate cancer: A multi-institutional collaboration. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024, 28, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, H.; Mizuno, K.; Shiota, M.; Narita, S.; Terada, N.; Fujimoto, N.; Ogura, K.; Hatano, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Hakozaki, N.; et al. Prognostic significance of pathogenic variants in BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM and PALB2 genes in men undergoing hormonal therapy for advanced prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 1680–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, N.G.; Kasi, A. Docetaxel. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537242/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; et al. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.J.; Prencipe, M.; Dowling, C.; Fan, Y.; Mulrane, L.; Gallagher, W.M.; O’Connor, D.; O’Connor, R.; Devery, A.; Corcoran, C.; et al. Characterisation and manipulation of docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasendra, M.; Tovaglieri, A.; Sontheimer-Phelps, A.; Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S.; Bein, A.; Chalkiadaki, A.; Scholl, W.; Zhang, C.; Rickner, H.; Richmond, C.A.; et al. Development of a primary human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip using biopsy-derived organoids. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberg, N.; Hoehnel, S.; Kuttler, F.; Homicsko, K.; Ceroni, C.; Ringel, T.; Gjorevski, N.; Schwank, G.; Coukos, G.; Turcatti, G.; et al. High-throughput automated organoid culture via stem-cell aggregation in microcavity arrays. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmad, H.F.; Jalloul, M.; Azar, J.; Moubarak, M.M.; Samad, T.A.; Mukherji, D.; Al-Sayegh, M.; Abou-Kheir, W. Tumor Microenvironment in Prostate Cancer: Toward Identification of Novel Molecular Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy Development. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 652747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L. Tumor microenvironment heterogeneity an important mediator of prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. npj Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Z.; McCray, T.; Marsili, J.; Zenner, M.L.; Manlucu, J.T.; Garcia, J.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A.; Murray, M.; Voisine, C.; Murphy, A.B.; et al. Prostate Stroma Increases the Viability and Maintains the Branching Phenotype of Human Prostate Organoids. iScience 2019, 12, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.J.; Shin, T.H.; Kim, M.; Sung, C.O.; Jang, S.J.; Jeong, G.S. A one-stop microfluidic-based lung cancer organoid culture platform for testing drug sensitivity. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 2854–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voabil, P.; de Bruijn, M.; Roelofsen, L.M.; Hendriks, S.H.; Brokamp, S.; van den Braber, M.; Broeks, A.; Sanders, J.; Herzig, P.; Zippelius, A.; et al. An ex vivo tumor fragment platform to dissect response to PD-1 blockade in cancer. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Yun, S.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.W.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, G.D.; Joo, S.T.; Choi, I.; et al. Review of the Current Research on Fetal Bovine Serum and the Development of Cultured Meat. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2022, 42, 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Khera, M. Physiological normal levels of androgen inhibit proliferation of prostate cancer cells in vitro. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Fiandalo, M.V.; Pop, E.; Stocking, J.J.; Azabdaftari, G.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Ma, D.; Qu, J.; Mohler, J.L.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Charcoal-Stripped Fetal Bovine Serum Reveals Changes in the Insulin-like Growth Factor Signaling Pathway. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, T.; Mikheeva, A.; Gasca, V.; Spirin, P.; Prassolov, V. Systematic Comparison of FBS and Medium Variation Effect on Key Cellular Processes Using Morphological Profiling. Cells 2025, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Fetal bovine serum, an important factor affecting the reproducibility of cell experiments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, J.P.; Ertunc, O.; Kulac, I.; Baena-Del Valle, J.A.; De Marzo, A.M.; Sfanos, K.S. IL8 Expression Is Associated with Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness and Androgen Receptor Loss in Primary and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Lee, J.K.; Phillips, J.W.; Huang, P.; Cheng, D.; Huang, J.; Witte, O.N. Prostate epithelial cell of origin determines cancer differentiation state in an organoid transformation assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4482–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, M.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Z.; Ji, Y.; Shen, K.; Xin, Z.; Qi, J.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of androgen receptor status in prostate cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 955166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völkel, C.; De Wispelaere, N.; Weidemann, S.; Gorbokon, N.; Lennartz, M.; Luebke, A.M.; Hube-Magg, C.; Kluth, M.; Fraune, C.; Möller, K.; et al. Cytokeratin 5 and cytokeratin 6 expressions are unconnected in normal and cancerous tissues and have separate diagnostic implications. Virchows Arch. 2022, 480, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.M.; Higgins, J.P.; Sangoi, A.R.; McKenney, J.K.; Troxell, M.L. Androgen receptor immunohistochemistry in genitourinary neoplasms. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2015, 47, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D.R.; Silvestri, V.; Leslie, G.; McGuffog, L.; Dennis, J.; Yang, X.; Adlard, J.; Agnarsson, B.A.; Ahmed, M.; Aittomäki, K.; et al. Breast and Prostate Cancer Risks for Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers Using Polygenic Risk Scores. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopsack, K.H.; Gerke, T.; Zareba, P.; Pettersson, A.; Chowdhury, D.; Ebot, E.M.; Flavin, R.; Finn, S.; Kantoff, P.W.; Stampfer, M.J.; et al. Tumor protein expression of the DNA repair gene BRCA1 and lethal prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.F.; Hjelmeland, M.E.; Lien, H.; Espedal, H.; Fonnes, T.; Srivastava, A.; Stokowy, T.; Strand, E.; Bozickovic, O.; Stefansson, I.M.; et al. Patient-derived organoids reflect the genetic profile of endometrial tumors and predict patient prognosis. Commun. Med. 2021, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolia, A.; Cieslik, M.; Chu, S.-C.; Xiao, L.; Ouchi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Vats, P.; Cao, X.; Pitchiaya, S.; et al. Distinct structural classes of activating FOXA1 alterations in advanced prostate cancer. Nature 2019, 571, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Hollstein, M.; Hainaut, P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a001008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.N.; Cheng, H.H.; Powers, J.; Gulati, R.; Ledet, E.M.; Morrison, C.; Le, A.; Hausler, R.; Stopfer, J.; Hyman, S.; et al. Inherited TP53 Variants and Risk of Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Sartor, O.; Zhang, K. Deciphering the Increased Prevalence of TP53 Mutations in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancer Inform. 2022, 21, 11769351221087046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economides, M.P.; Nakazawa, M.; Lee, J.W.; Li, X.; Hollifield, L.; Chambers, R.; Sarfaty, M.; Goldberg, J.D.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Wise, D.R. Case Series of Men with the Germline APC I1307K variant and Treatment-Emergent Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2024, 22, e31–e37.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.W.; Lee, I.H.; Liu, X.; Hirschhorn, J.N.; Mandl, K.D. Measuring coverage and accuracy of whole-exome sequencing in clinical context. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatano, K.; Nonomura, N. Genomic Profiling of Prostate Cancer: An Updated Review. World J. Mens Health 2022, 40, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, M.C.; Zwart, W.; Roudier, M.P.; True, L.D.; Nelson, W.G.; Epstein, J.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Nelson, P.S.; Yegnasubramanian, S. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henzler, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; McBride, T.; Ho, Y.; Sprenger, C.; Liu, G.; Coleman, I.; Lakely, B.; Li, R.; et al. Truncation and constitutive activation of the androgen receptor by diverse genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Years |

|---|---|

| Median (range) | 71.34 (40–90) |

| Types of tissue collections | Cases |

| Transurethral Resection of the Prostate | 28 |

| Radical prostatectomy | 1 |

| Gleason score | N (%) |

| 6 | 1 (3.45%) |

| 7 | 6 (20.69%) |

| 8 | 7 (24.14%) |

| 9 | 13 (44.83%) |

| 10 | 2 (6.90%) |

| PSA level before treatments | ng/mL |

| Median (range) | 236.97 (1–1561) |

| PSA level after treatments | ng/mL |

| Median (range) of 26 sensitive patients | 26.10 (0.025–300) |

| Median (range) of 1 resistant patient | >1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, Z.B.; Plikomol, M.; Bejrananda, T.; Thongsuksai, P.; Khirilak, P.; Khongcharoen, N.; Ulhaka, K.; Nontikarn, R.; Phanthuvet, O.; Khongkow, P. A Patient-Derived Organoid Platform from TUR-P Samples Enables Precision Drug Screening in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3973. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243973

Ali ZB, Plikomol M, Bejrananda T, Thongsuksai P, Khirilak P, Khongcharoen N, Ulhaka K, Nontikarn R, Phanthuvet O, Khongkow P. A Patient-Derived Organoid Platform from TUR-P Samples Enables Precision Drug Screening in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3973. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243973

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Zaukir Bostan, Mooktapa Plikomol, Tanan Bejrananda, Paramee Thongsuksai, Pokphon Khirilak, Natthapon Khongcharoen, Karan Ulhaka, Ratsamaporn Nontikarn, Onpawee Phanthuvet, and Pasarat Khongkow. 2025. "A Patient-Derived Organoid Platform from TUR-P Samples Enables Precision Drug Screening in Advanced Prostate Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3973. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243973

APA StyleAli, Z. B., Plikomol, M., Bejrananda, T., Thongsuksai, P., Khirilak, P., Khongcharoen, N., Ulhaka, K., Nontikarn, R., Phanthuvet, O., & Khongkow, P. (2025). A Patient-Derived Organoid Platform from TUR-P Samples Enables Precision Drug Screening in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cancers, 17(24), 3973. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243973