Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Therapies Have the Potential to Treat Ovarian Cancer Effectively by Targeting Diverse Tumor Populations and Reducing the Risk of Recurrence

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Factors Contributing to Late-Stage Detection of Ovarian Cancer

3. Impaired Immune Function in Peripheral Blood and Tumor Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer Patients

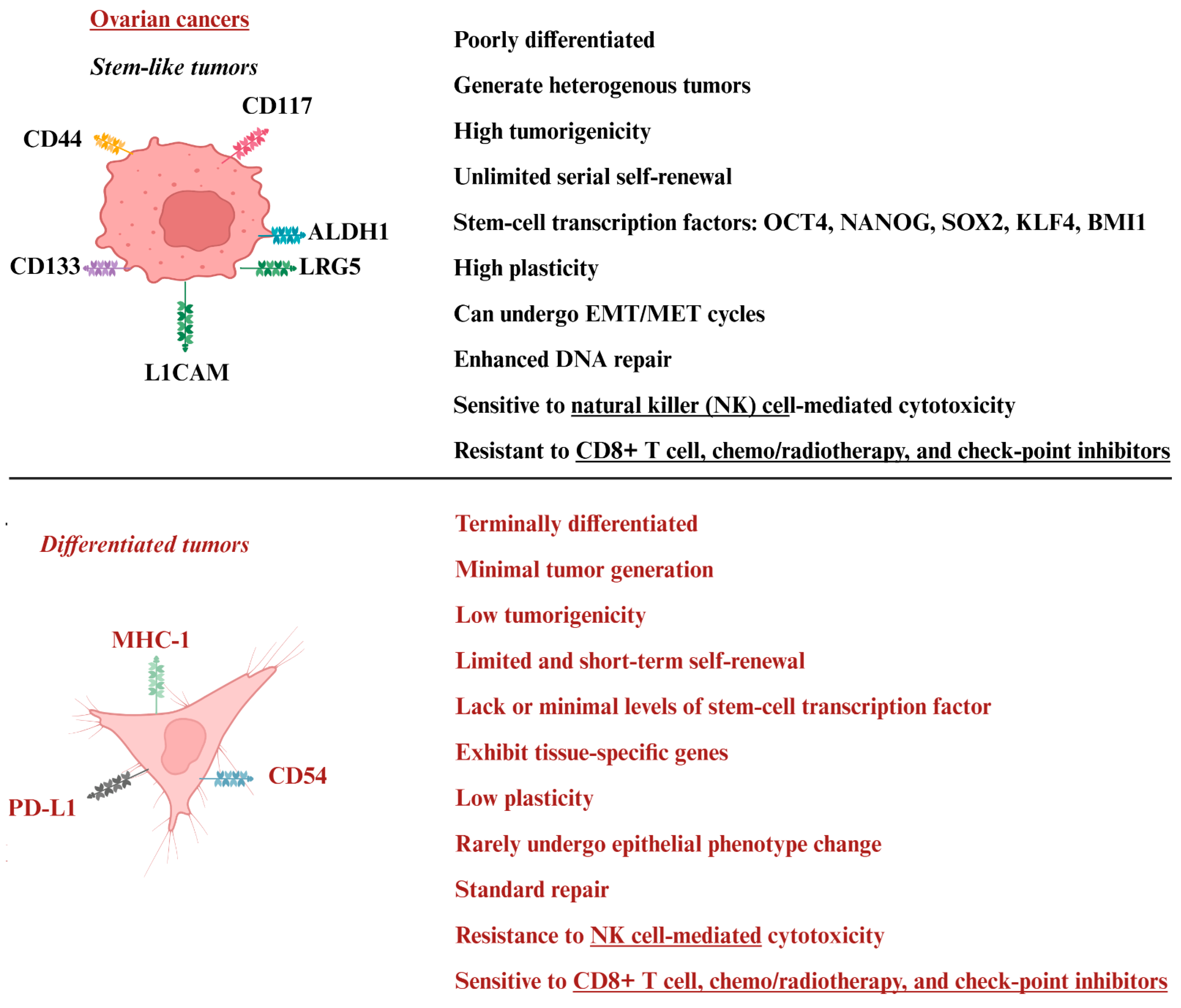

4. Tumor Heterogeneity in Ovarian Cancer

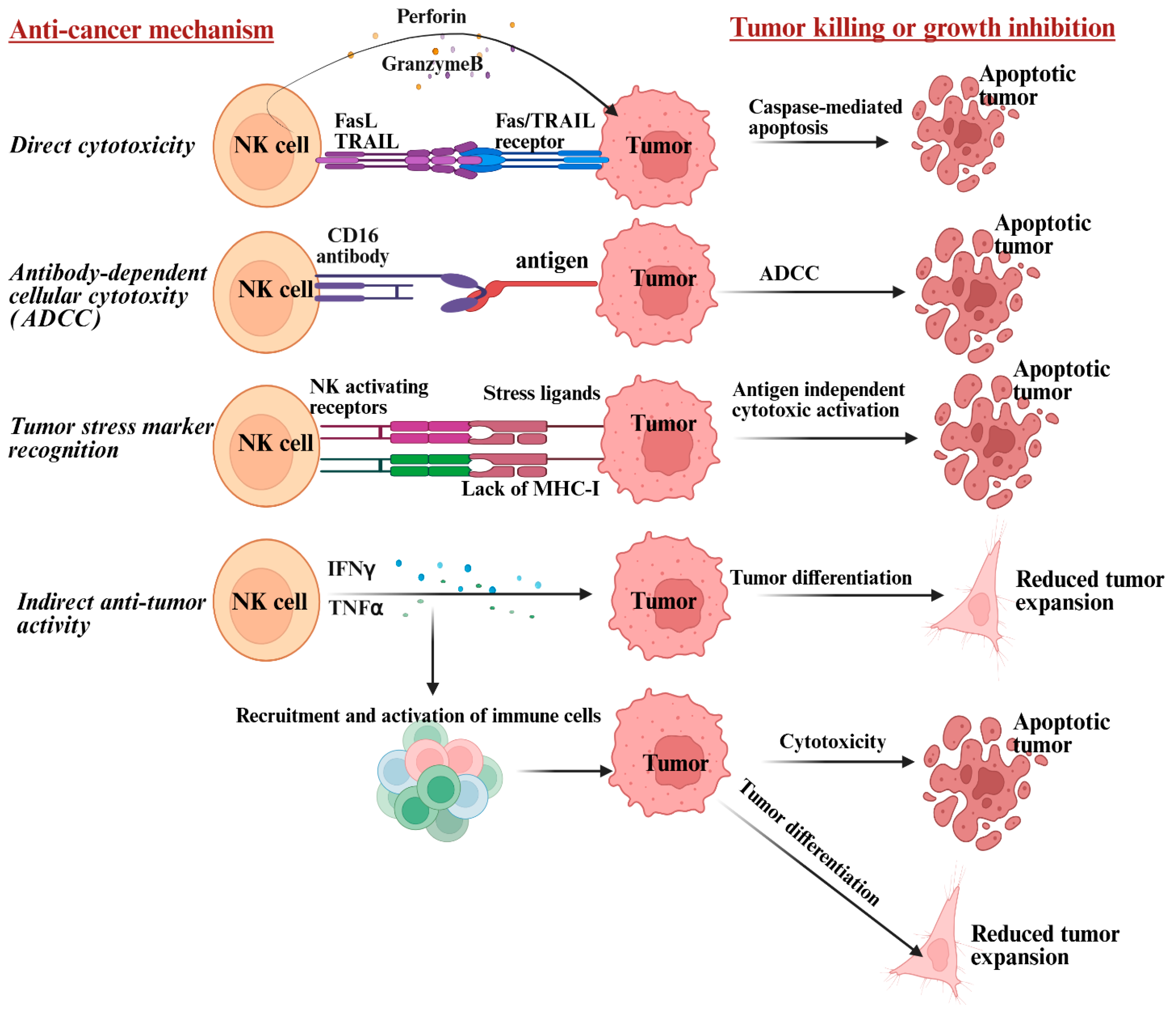

5. Mechanism by Which NK Cells Target Heterogeneous Tumor Populations and Limit Recurrence of Ovarian Cancer

6. Main Differences Between T Cells and NK Cells in Targeting Ovarian Cancer

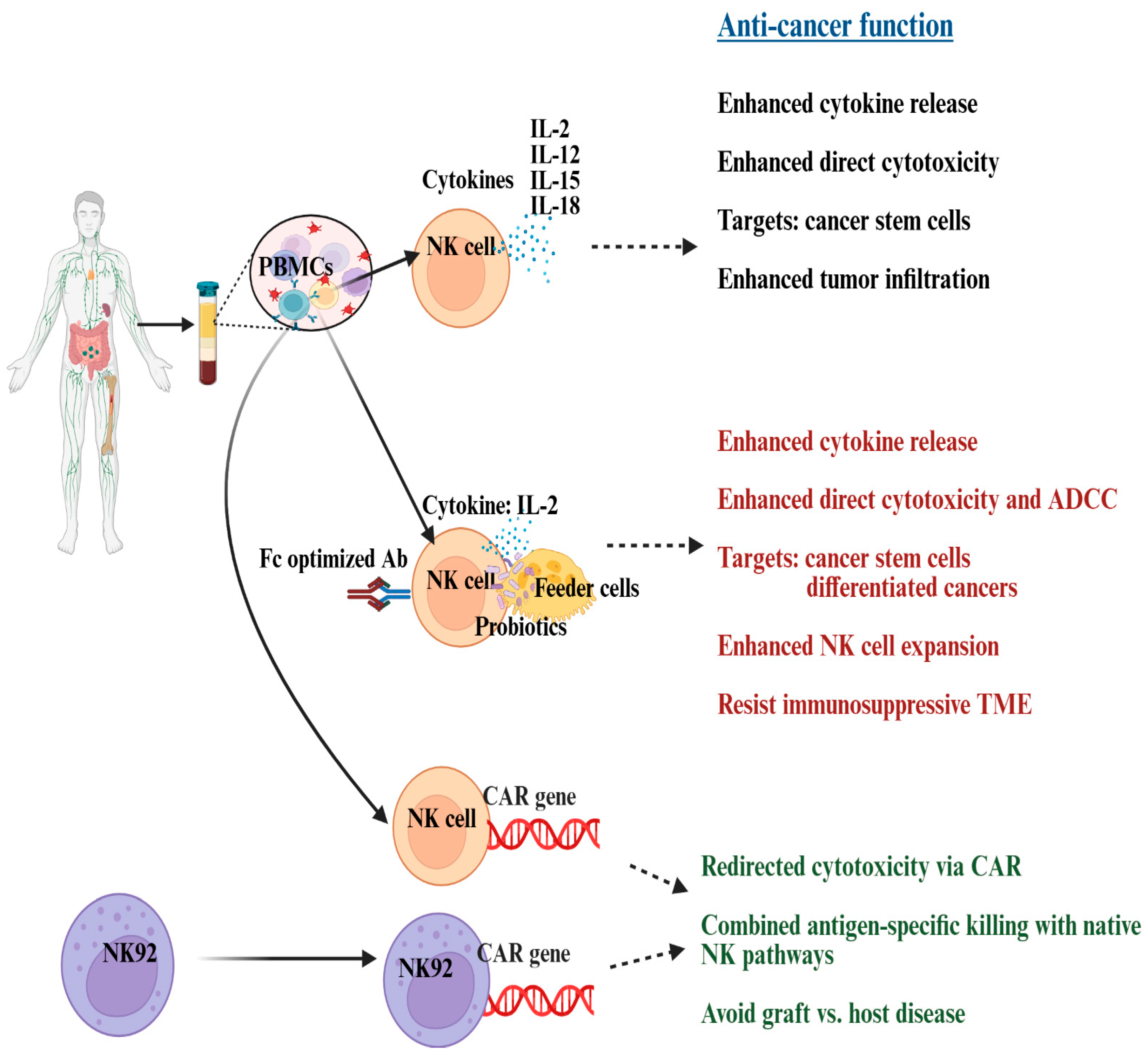

7. Current Ovarian Cancer Treatments and Their Limitations: How NK Cells Can Benefit

8. Challenges to Developing NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy

9. Progress in NK Cell-Based Therapies for Ovarian Cancer: Insights from Preclinical Studies

10. Progress in NK Cell-Based Therapies for Ovarian Cancer: Insights from Clinical Studies

11. Challenges and Limitations of NK Cell-Based Therapies for Ovarian Cancer

| Challenge/Limitation | Potential Solutions: Developing NK Cell-Based Therapies | Strategies for Therapeutic Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited survival and proliferation in vivo | - Genetic engineering (e.g., CAR, IL-15 transgene) -Cytokine support (IL-2, IL-15, IL-21) to generate memory like NK cells - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics | Combine with cytokine therapy or checkpoint inhibitors to sustain activity | [25,167,169,196,215] |

| Poor trafficking and infiltration into solid tumors: due to physical barriers and low chemokine levels | - Chemokine receptor engineering (e.g., CXCR4, CCR7) - Preconditioning regimens to remodel stroma | Combine with oncolytic viruses or stromal-targeting drugs to enhance infiltration | [48,196,216,217] |

| Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME): Tumors secrete TGF-β, IL-10, and express inhibitory ligands that suppress NK function | - Blockade of inhibitory pathways (e.g., anti-TGF-β, anti-PD-1/PD-L1) - Metabolic reprogramming - Cytokine support (IL-2, IL-15, IL-21) to generate memory like NK cells - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics | Combine NK therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors or metabolic modulators | [41,42,169,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,216,218]. |

| Tumors can evade NK cells by releasing soluble ligands or by upregulating MHC-class I: soluble ligands can further inhibit NK cells’ anti-cancer activity | - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics - Cytokine support (IL-2, IL-15, IL-21) to generate memory like NK cells | -Modification of TME -Personalized approaches of tailoring NK cell therapies based on tumor immunogenicity | [196,198,199,200]. |

| Limited tumor specificity: NK cells rely on natural cytotoxicity, which may not be sufficient for heterogeneous tumors | - CAR-NK cells engineered with tumor-specific receptors - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics | - Combine CAR-NK with monoclonal antibodies (ADCC) or bispecific engagers -Modification of TME -Personalized approach | [215,216] |

| Manufacturing and scalability issues: Difficulty in producing large, standardized NK cell products | - Use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), cord blood, or NK cell lines as “off-the-shelf” sources - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics | - Combine with universal donor platforms and cryopreservation technologies | [215] |

| Risk of limited efficacy compared to CAR-T: NK cells show lower persistence and potency in some cancers | - Optimize CAR constructs, enhance signaling domains, and improve expansion protocols | - Combine CAR-NK with CAR-T or other immune therapies for synergistic effects | [215,216,217] |

| Potential toxicity and safety concerns: Vascular leak syndrome and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) are less common but possible. | - Careful dose escalation, suicide gene switches, safety switches in engineered NK cells - Supercharging using osteoclasts as feeder cells combined with probiotics | - Combine with supportive therapies to mitigate toxicity | [48,169,197,215] |

| Allogenic NK cells: Immune rejection and limited persistence from HLA mismatches | - Selecting donors based on KIR and HLA compatibility | -Repeated dosing | [208,209,210,211] |

12. Exploring Future Strategies to Enhance the Effectiveness of NK Cell-Based Therapies for Ovarian Cancer

13. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| NK | Natural killer |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CD | C-Reactive protein |

| NKG2D | Natural killer group 2D |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ADCC | Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand-1 |

| MHC-I | Major histocompatibility complex-class I |

| MICA/B | MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A and B |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

| TIL | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| KIR | Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors |

| HLA | Human leucocyte antigen |

References

- Ren, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Su, L.; Su, J. Global, regional, and national burden of ovarian cancer in women aged 45 + from 1990 to 2021 and projections for 2050: A systematic analysis based on the 2021 global burden of disease study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.T.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Prz. Menopauzalny 2023, 22, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, L.; Harley, I.J.; McCluggage, W.G.; Mullan, P.B.; Beirne, J.P. Liquid biopsy in ovarian cancer: Catching the silent killer before it strikes. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 11, 868–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Pietrocola, F.; Roiz-Valle, D.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Wang, B.; Demaria, M. Senescence and cancer—Role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Ovarian cancer targeted therapy: Current landscape and future challenges. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1535235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oronsky, B.; Ray, C.M.; Spira, A.I.; Trepel, J.B.; Carter, C.A.; Cottrill, H.M. A brief review of the management of platinum-resistant-platinum-refractory ovarian cancer. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.K.; Ding, D.C. Early Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of the Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xia, B.R.; Zhang, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Lou, G.; Jin, W.L. Immunotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: Adjuvant, Combination, and Neoadjuvant. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 577869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duwa, R.; Jeong, J.-H.; Yook, S. Immunotherapeutic strategies for the treatment of ovarian cancer: Current status and future direction. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 94, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Jacobs, M.T.; Fehniger, T.A. Allogeneic natural killer cell therapy. Blood 2023, 141, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera Molligoda Arachchige, A.S. Human NK cells: From development to effector functions. Innate Immun. 2021, 27, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.A.; Fehniger, T.A.; Turner, S.C.; Chen, K.S.; Ghaheri, B.A.; Ghayur, T.; Carson, W.E.; Caligiuri, M.A. Human natural killer cells: A unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood 2001, 97, 3146–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, A.M.; Yang, C.; Thakar, M.S.; Malarkannan, S. Natural Killer Cells: Development, Maturation, and Clinical Utilization. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 01869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, P.; Rancan, C.; Ma, W.; Toth, M.; Senda, T.; Carpenter, D.J.; Kubota, M.; Matsumoto, R.; Thapa, P.; Szabo, P.A.; et al. Tissue Determinants of Human NK Cell Development, Function, and Residence. Cell 2020, 180, 749–763.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.N.; Yuan, O.; Kanaya, M.; Telliam-Dushime, G.; Li, H.; Kotova, O.; Caglar, E.; Honnens de Lichtenberg, K.; Rahman, S.H.; Soneji, S.; et al. A temporal developmental map separates human NK cells from noncytotoxic ILCs through clonal and single-cell analysis. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 2933–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, E.M. Human natural killer cells: Form, function, and development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskalenko, N.A.; Zahroun, S.; Tsygankova, O.; Anikeeva, N.; Sykulev, Y.; Campbell, K.S. The FcγRIIIA (CD16) L48-H/R Polymorphism Enhances NK Cell-Mediated Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity by Promoting Serial Killing. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Larrea, C.; López-Soto, A.; González, S. Chapter Five—NK cell immune recognition: NKG2D ligands and stressed cells. In Natural Killer Cells; Lotze, M.T., Thomson, A.W., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth, K.; Silva-Santos, B.; Mavilio, D. Natural cytotoxicity receptors: Broader expression patterns and functions in innate and adaptive immune cells. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Fan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Niu, J.; Dong, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, W. The role of NK cells in regulating tumorimmunity: Current state, challenges and future strategies. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coënon, L.; Geindreau, M.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Villalba, M.; Bruchard, M. Natural Killer cells at the frontline in the fight against cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chovatiya, N.; Kaur, K.; Huerta-Yepez, S.; Chen, P.-C.; Neal, A.; DiBernardo, G.; Gumrukcu, S.; Memarzadeh, S.; Jewett, A. Inability of ovarian cancers to upregulate their MHC-class I surface expression marks their aggressiveness and increased susceptibility to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 2929–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Yepez, S.; Chen, P.C.; Kaur, K.; Jain, Y.; Singh, T.; Esedebe, F.; Liao, Y.J.; DiBernardo, G.; Moatamed, N.A.; Mei, A.; et al. Supercharged NK cells, unlike primary activated NK cells, effectively target ovarian cancer cells irrespective of MHC-class I expression. BMJ Oncol. 2025, 4, e000618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Rodgers Furones, A.; Gultekin, O.; Khare, S.; Neo, S.Y.; Shi, W.; Moyano-Galceran, L.; Lam, K.-P.; Dasgupta, R.; Fuxe, J.; et al. Adaptive NK Cells Exhibit Tumor-Specific Immune Memory and Cytotoxicity in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 1080–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberto, J.M.; Chen, S.Y.; Shih, I.M.; Wang, T.H.; Wang, T.L.; Pisanic, T.R., 2nd. Current and Emerging Methods for Ovarian Cancer Screening and Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsas, A.; Stefanoudakis, D.; Troupis, T.; Kontzoglou, K.; Eleftheriades, M.; Christopoulos, P.; Panoskaltsis, T.; Stamoula, E.; Iliopoulos, D.C. Tumor Markers and Their Diagnostic Significance in Ovarian Cancer. Life 2023, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; Krist, A.H.; Kurth, A.E.; et al. Screening for Ovarian Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; McCann, L.; Makker, S.; Mukherjee, U.; Gullapalli, S.V.N.; Erekkath, J.; Shih, S.; Mahajan, I.; Sanchez, E.; Uccello, M.; et al. Diagnostic biomarkers in ovarian cancer: Advances beyond CA125 and HE4. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241233225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, U.S.; Kohale, M.G.; Jaiswal, N.; Wankhade, R. Emerging Applications of Liquid Biopsies in Ovarian Cancer. Cureus 2023, 15, e49880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, J.; Burnell, M.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Ryan, A.; Neophytou, C.; Apostolidou, S.; Karpinskyj, C.; Kalsi, J.; Mould, T.; Woolas, R.; et al. Ovarian cancer symptoms, routes to diagnosis and survival—Population cohort study in the ‘no screen’ arm of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisio, M.A.; Fu, L.; Goyeneche, A.; Gao, Z.H.; Telleria, C. High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Basic Sciences, Clinical and Therapeutic Standpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Ding, Q.; Tao, Z. Molecular characteristics of early- and late-onset ovarian cancer: Insights from multidimensional evidence. J. Ovarian Res. 2025, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kumar, R.; Penn, C.A.; Wajapeyee, N. Immune evasion in ovarian cancer: Implications for immunotherapy and emerging treatments. Trends Immunol. 2025, 46, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yin, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, L.; Wang, J. Inflammation and Immune Escape in Ovarian Cancer: Pathways and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajtak, A.; Ostrowska-Leśko, M.; Żak, K.; Tarkowski, R.; Kotarski, J.; Okła, K. Integration of local and systemic immunity in ovarian cancer: Implications for immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1018256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havasi, A.; Cainap, S.S.; Havasi, A.T.; Cainap, C. Ovarian Cancer-Insights into Platinum Resistance and Overcoming It. Medicina 2023, 59, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Sheng, J.-J.; Zheng, S.-A.; Liu, P.-W.; Wu, N.; Zeng, W.-J.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, J. Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: From mechanisms to treatment strategies. Genes. Dis. 2025, 13, 101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-García, I.; Uhlitz, F.; Ceglia, N.; Lim, J.L.P.; Wu, M.; Mohibullah, N.; Niyazov, J.; Ruiz, A.E.B.; Boehm, K.M.; Bojilova, V.; et al. Ovarian cancer mutational processes drive site-specific immune evasion. Nature 2022, 612, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, M.; Huang, B.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, B.; Zhou, H.; Huang, T.; Li, M.; et al. Tumor cells promote immunosuppression in ovarian cancer via a positive feedback loop with MDSCs through the SAA1–IL-1β axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, H.; Xie, R.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Wan, L. Immunosuppressive mechanisms and therapeutic targeting of regulatory T cells in ovarian cancer. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1631226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulak, J.; Terzoli, S.; Marzano, P.; Cazzetta, V.; Martiniello, G.; Piazza, R.; Viano, M.E.; Vitobello, D.; Portuesi, R.; Grizzi, F.; et al. Immune evasion mechanisms in early-stage I high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: Insights into regulatory T cell dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okła, K. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) in Ovarian Cancer-Looking Back and Forward. Cells 2023, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, N.; Ji, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Xu, S.; Li, H. Unraveling the role of M2 TAMs in ovarian cancer dynamics: A systematic review. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ma, P.; Zeng, S.; Ju, D.; Zhao, M.; Yu, M.; Shi, Y. Regulatory T cells in homeostasis and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Elkord, E. FoxP3+ T regulatory cells in cancer: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2020, 490, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Han, D.; Fan, X.; Zhao, L. Ovarian cancer treatment and natural killer cell-based immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1308143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greppi, M.; Tabellini, G.; Patrizi, O.; Obino, V.; Bozzo, M.; Rutigliani, M.; Gorlero, F.; Di Luca, M.; Paleari, L.; Melaiu, O.; et al. PD-1+ NK cell subsets in high grade serous ovarian cancer: An indicator of disease severity and a target for combined immune-checkpoint blockade. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worzfeld, T.; Pogge von Strandmann, E.; Huber, M.; Adhikary, T.; Wagner, U.; Reinartz, S.; Müller, R. The Unique Molecular and Cellular Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chap, B.S.; Rayroux, N.; Grimm, A.J.; Ghisoni, E.; Dangaj Laniti, D. Crosstalk of T cells within the ovarian cancer microenvironment. Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowich, H.; Suminami, Y.; Reichert, T.E.; Crowley-Nowick, P.; Bell, M.; Edwards, R.; Whiteside, T.L. Expression of cytokine genes or proteins and signaling molecules in lymphocytes associated with human ovarian carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 1996, 68, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukesova, S.; Vroblova, V.; Tosner, J.; Kopecky, J.; Sedlakova, I.; Čermáková, E.; Vokurkova, D.; Kopecky, O. Comparative study of various subpopulations of cytotoxic cells in blood and ascites from patients with ovarian carcinoma. Contemp. Oncol. 2015, 19, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalos, A.; Neri, O.; Ercan, C.; Wilhelm, A.; Staubli, S.; Posabella, A.; Weixler, B.; Terracciano, L.; Piscuoglio, S.; Stadlmann, S.; et al. High Density of CD16+ Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer Is Associated with Enhanced Responsiveness to Chemotherapy and Prolonged Overall Survival. Cancers 2021, 13, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berek, J.S.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Lichtenstein, A.; Hacker, N.F.; Spina, C.A.; Lagasse, L.D.; Knapp, R.C.; Zighelboim, J. Lymphocyte cytotoxicity in the peritoneal cavity and blood of patients with ovarian cancer. Obs. Gynecol. 1984, 64, 708–714. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadially, H.; Brown, L.; Lloyd, C.; Lewis, L.; Lewis, A.; Dillon, J.; Sainson, R.; Jovanovic, J.; Tigue, N.J.; Bannister, D.; et al. MHC class I chain-related protein A and B (MICA and MICB) are predominantly expressed intracellularly in tumour and normal tissue. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari de Andrade, L.; Tay, R.E.; Pan, D.; Luoma, A.M.; Ito, Y.; Badrinath, S.; Tsoucas, D.; Franz, B.; May, K.F.; Harvey, C.J.; et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell–driven tumor immunity. Science 2018, 359, 1537–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y. The role of NKG2D-MICA in the immune escape mechanism of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 190, S224–S225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Nie, Y.; Mi, Q.; Zhao, S. Ovarian tumor-associated microRNA-20a decreases natural killer cell cytotoxicity by downregulating MICA/B expression. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Miao, Z.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, Y.; Niu, Z.; Xu, Q. The emerging role of glycolysis and immune evasion in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Orsulic, S.; Matei, D. Metabolic dependencies and targets in ovarian cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 245, 108413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Katsaros, D.; Gimotty, P.A.; Massobrio, M.; Regnani, G.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Gray, H.; Schlienger, K.; Liebman, M.N.; et al. Intratumoral T Cells, Recurrence, and Survival in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinty, M.T.; Putelo, A.M.; Kolli, S.H.; Feng, T.Y.; Dietl, M.R.; Hatzinger, C.N.; Bajgai, S.; Poblete, M.K.; Azar, F.N.; Mohammad, A.; et al. TLR5 Signaling Causes Dendritic Cell Dysfunction and Orchestrates Failure of Immune Checkpoint Therapy against Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2025, 13, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubovich, E.; Cook, D.P.; Rodriguez, G.M.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Mesenchymal ovarian cancer cells promote CD8(+) T cell exhaustion through the LGALS3-LAG3 axis. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2023, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launonen, I.-M.; Niemiec, I.; Hincapié-Otero, M.; Erkan, E.P.; Junquera, A.; Afenteva, D.; Falco, M.M.; Liang, Z.; Salko, M.; Chamchougia, F.; et al. Chemotherapy induces myeloid-driven spatially confined T cell exhaustion in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 2045–2063.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Borzyszkowska, D.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. The Role of TIM-3 and LAG-3 in the Microenvironment and Immunotherapy of Ovarian Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.E.; Lyons, P.M.; Kilgallon, A.M.; Simpson, J.C.; Perry, A.S.; Lysaght, J. Examining the evidence for immune checkpoint therapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, Q.; Chen, X.; Aifantis, I. Targeting MHC-I inhibitory pathways for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2024, 45, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Yi, P. Shaping Immune Responses in the Tumor Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 692360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Huang, X.; Song, Z.; Ye, L.; Zhou, G. The expression and clinical significance of cytokines Th1, Th2, and Th17 in ovarian cancer. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 369, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuno, A.; Matsushita, H.; Hamano, T.; Tan, T.Z.; Shintani, D.; Fujieda, N.; Tan, D.S.P.; Huang, R.Y.; Fujiwara, K.; Kakimi, K.; et al. Identification of serum cytokine clusters associated with outcomes in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Zheng, X.; Huang, Y.; Wei, W.; Xu, S.; Chen, S.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, M. The efficacy and peripheral blood predictors in recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Ovarian Res. 2025, 18, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Dobrica, E.C.; Croitoru, A.; Cretoiu, S.M.; Gaspar, B.S. Focus on PD-1/PD-L1 as a Therapeutic Target in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamwar, U.M.; Anjankar, A.P. Aetiology, Epidemiology, Histopathology, Classification, Detailed Evaluation, and Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Cureus 2022, 14, e30561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, A.C.; Gonzalez-Ochoa, E.; Alqaisi, H.; Madariaga, A.; Bhat, G.; Rouzbahman, M.; Sneha, S.; Oza, A.M. Heterogeneity and treatment landscape of ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 820–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Shao, F.; Tian, Y.; Chen, S. Genomic and clinical insights into ovarian cancer: Subtype-specific alterations and predictors of metastasis and relapse. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.; Kotani, Y.; Nakai, H.; Matsumura, N. Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer: The Origin and Targeted Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Kimura, T. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: Molecular insights and future therapeutic perspectives. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaier, A.; Mal, H.; Alselwi, W.; Ghatage, P. Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma of the Ovary: The Current Status. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varier, L.; Sundaram, S.M.; Gamit, N.; Warrier, S. An Overview of Ovarian Cancer: The Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Chemoresistance and a Precision Medicine Approach Targeting the Wnt Pathway with the Antagonist sFRP4. Cancers 2023, 15, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, H.; Akbarabadi, P.; Dadfar, A.; Tareh, M.R.; Soltani, B. A comprehensive overview of ovarian cancer stem cells: Correlation with high recurrence rate, underlying mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, J.R.; Wilczyński, M.; Paradowska, E. Cancer Stem Cells in Ovarian Cancer-A Source of Tumor Success and a Challenging Target for Novel Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhou, S. Deciphering the “Rosetta Stone” of ovarian cancer stem cells: Opportunities and challenges. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Tian, T.; Cui, Z. Targeting ovarian cancer stem cells: A new way out. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, N.; Christie, E.L.; Ardasheva, A.; Kwok, C.H.; Demchenko, N.; Low, C.; Tralau-Stewart, C.; Fotopoulou, C.; Cunnea, P. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in epithelial ovarian cancer, therapeutic treatment options for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Królewska-Daszczyńska, P.; Wendlocha, D.; Smycz-Kubańska, M.; Stępień, S.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A. Cancer stem cells markers in ovarian cancer: Clinical and therapeutic significance (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2022, 24, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Che, Y. Ovarian cancer stem cells: Critical roles in anti-tumor immunity. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 998220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Tan, Q. The role of macrophage polarization in ovarian cancer: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic potentials. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1543096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Chen, P.-C.; Jewett, A. Supercharged NK cells: A unique population of NK cells capable of differentiating stem cells and lysis of MHC class I high differentiated tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, V.; Marques, I.S.; Melo, I.G.; Assis, J.; Pereira, D.; Medeiros, R. Paradigm Shift: A Comprehensive Review of Ovarian Cancer Management in an Era of Advancements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, A.K.; Topchyan, P.; Kaur, K.; Tseng, H.C.; Teruel, A.; Hiraga, T.; Jewett, A. Differentiation by NK cells is a prerequisite for effective targeting of cancer stem cells/poorly differentiated tumors by chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic drugs. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Mao, M.; Gong, Y.; Li, X.; Lei, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, S.; Hu, Q. T-cell infiltration and its regulatory mechanisms in cancers: Insights at single-cell resolution. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Sun, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Immune cell landscapes are associated with high-grade serous ovarian cancer survival. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordo-Bahamonde, C.; Lorenzo-Herrero, S.; Payer, Á.R.; Gonzalez, S.; López-Soto, A. Mechanisms of Apoptosis Resistance to NK Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, A.; Kos, J.; Kaur, K.; Safaei, T.; Sutanto, C.; Chen, W.; Wong, P.; Namagerdi, A.K.; Fang, C.; Fong, Y.; et al. Natural Killer Cells: Diverse Functions in Tumor Immunity and Defects in Pre-neoplastic and Neoplastic Stages of Tumorigenesis. Mol. Ther.—Oncolytics 2020, 16, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, S.P.; Martin, S.J. Fas and TRAIL ‘death receptors’ as initiators of inflammation: Implications for cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 39, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Safaie, T.; Ko, M.-W.; Wang, Y.; Jewett, A. ADCC against MICA/B Is Mediated against Differentiated Oral and Pancreatic and Not Stem-Like/Poorly Differentiated Tumors by the NK Cells; Loss in Cancer Patients due to Down-Modulation of CD16 Receptor. Cancers 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Churov, A.; Fu, R. Research Progress on NK Cell Receptors and Their Signaling Pathways. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 6437057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Lal, G. The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Killer Cells Function and Its Importance in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, L.T.H.; Sari, I.N.; Yang, Y.G.; Lee, S.H.; Jun, N.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 5416923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.T.; Tseng, H.-C.; Kozlowska, A.; Maung, P.O.; Kaur, K.; Topchyan, P.; Jewett, A. Augmented IFN-γ and TNF-α Induced by Probiotic Bacteria in NK Cells Mediate Differentiation of Stem-Like Tumors Leading to Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Reduction in Inflammatory Cytokine Release; Regulation by IL-10. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Kozlowska, A.K.; Topchyan, P.; Ko, M.W.; Ohanian, N.; Chiang, J.; Cook, J.; Maung, P.O.; Park, S.H.; Cacalano, N.; et al. Probiotic-Treated Super-Charged NK Cells Efficiently Clear Poorly Differentiated Pancreatic Tumors in Hu-BLT Mice. Cancers 2019, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesinger, L.; Nyarko-Odoom, A.; Martinez, S.A.; Shen, N.W.; Ring, K.L.; Gaughan, E.M.; Mills, A.M. PD-L1 and MHC Class I Expression in High-grade Ovarian Cancers, Including Platinum-resistant Recurrences Treated With Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2023, 31, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, H.; Peper, J.K.; Bösmüller, H.C.; Röhle, K.; Backert, L.; Bilich, T.; Ney, B.; Löffler, M.W.; Kowalewski, D.J.; Trautwein, N.; et al. The immunopeptidomic landscape of ovarian carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9942–E9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, S.; Felix, S.; Auer, K.; Bachmayr-Heyda, A.; Kenner, L.; Dekan, S.; Meier, S.M.; Gerner, C.; Grimm, C.; Pils, D. Absence of PD-L1 on tumor cells is associated with reduced MHC I expression and PD-L1 expression increases in recurrent serous ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.B.; Meza-Perez, S.; Londoño, A.; Katre, A.; Peabody, J.E.; Smith, H.J.; Forero, A.; Norian, L.A.; Straughn, J.M., Jr.; Buchsbaum, D.J.; et al. Epigenetic modifiers upregulate MHC II and impede ovarian cancer tumor growth. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 44159–44170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Hang, J.F.; Lai, C.R.; Chan, I.S.; Shih, Y.C.; Jiang, L.Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Loss of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I, CD8 + Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes, and PD-L1 Expression in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2023, 47, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornel, A.M.; Mimpen, I.L.; Nierkens, S. MHC Class I Downregulation in Cancer: Underlying Mechanisms and Potential Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M.J.; Nagymanyoki, Z.; Bonome, T.; Johnson, M.E.; Litkouhi, B.; Sullivan, E.H.; Hirsch, M.S.; Matulonis, U.A.; Liu, J.; Birrer, M.J.; et al. Increased HLA-DMB expression in the tumor epithelium is associated with increased CTL infiltration and improved prognosis in advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7667–7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunekreeft, K.L.; Paijens, S.T.; Wouters, M.C.A.; Komdeur, F.L.; Eggink, F.A.; Lubbers, J.M.; Workel, H.H.; Van Der Slikke, E.C.; Pröpper, N.E.J.; Leffers, N.; et al. Deep immune profiling of ovarian tumors identifies minimal MHC-I expression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy as negatively associated with T-cell-dependent outcome. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1760705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Nanut, M.P.; Ko, M.-W.; Safaie, T.; Kos, J.; Jewett, A. Natural killer cells target and differentiate cancer stem-like cells/undifferentiated tumors: Strategies to optimize their growth and expansion for effective cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Batra, L. Memory Cells in Infection and Autoimmunity: Mechanisms, Functions, and Therapeutic Implications. Vaccines 2025, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.; Lee, Y.; Farber, D.L. A guide to adaptive immune memory. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 810–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, A.K.C.; Tang, W.T.; Li, P.H. Helper T cell subsets: Development, function and clinical role in hypersensitivity reactions in the modern perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder-Mengus, C.; Ghosh, S.; Weber, W.P.; Wyler, S.; Zajac, P.; Terracciano, L.; Oertli, D.; Heberer, M.; Martin, I.; Spagnoli, G.C.; et al. Multiple mechanisms underlie defective recognition of melanoma cells cultured in three-dimensional architectures by antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, T.K.; Singh, M.; Dhawan, M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Rabaan, A.A.; Mutair, A.A.; Alawi, Z.A.; Alhumaid, S.; Dhama, K. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their therapeutic potential against autoimmune disorders—Advances and challenges. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2035117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Fang, Z.; Gao, Z.J.; Li, W.G.; Yang, J. Comprehensive single-cell and bulk RNA-seq analyses reveal a novel CD8(+) T cell-associated prognostic signature in ovarian cancer. Aging 2024, 16, 10636–10656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, T.; Borghans, J.A.M.; van Wijk, F. The full spectrum of human naive T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Xiang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Kabelitz, D.; Wu, Y. γδ T cells: Origin and fate, subsets, diseases and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, J. Balancing act: The complex role of NK cells in immune regulation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1275028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, J.M.; Pauken, K.E. Localization, tissue biology and T cell state—Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, A.; Koksoy, S.; Vojdani, E.; Engelman, M.; Benzvi, C.; Lerner, A. Natural Killer Cells and Cytotoxic T Cells: Complementary Partners against Microorganisms and Cancer. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Jounaidi, Y. Comprehensive snapshots of natural killer cells functions, signaling, molecular mechanisms and clinical utilization. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, O.; Abhipsha, S.K.; Sen Santara, S. Power of Memory: A Natural Killer Cell Perspective. Cells 2025, 14, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Xie, S.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Yue, J.; Ma, J.; Shu, X.; He, Y.; Xiao, W.; Tian, Z. Advances in NK cell production. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuffet, L.; Melsen, J.E.; Escalière, B.; Basurto-Lozada, D.; Bhandoola, A.; Björkström, N.K.; Bryceson, Y.T.; Castriconi, R.; Cichocki, F.; Colonna, M.; et al. High-dimensional single-cell analysis of human natural killer cell heterogeneity. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 1474–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Fu, D.; Bidgoli, A.; Paczesny, S. T Cell Subsets in Graft Versus Host Disease and Graft Versus Tumor. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 761448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetta, F.; Alvarez, M.; Negrin, R.S. Natural Killer Cells in Graft-versus-Host-Disease after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.S.; Casanova, J.M.; Santos-Rosa, M.; Tarazona, R.; Solana, R.; Rodrigues-Santos, P. Natural Killer T-like Cells: Immunobiology and Role in Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Webb, T.J. Novel lipid antigens for NKT cells in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1173375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, N.M.S.; Bohmwald, K.; Pacheco, G.A.; Andrade, C.A.; Carreño, L.J.; Kalergis, A.M. Type I Natural Killer T Cells as Key Regulators of the Immune Response to Infectious Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00232-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijgsman, D.; Hokland, M.; Kuppen, P.J.K. The Role of Natural Killer T Cells in Cancer-A Phenotypical and Functional Approach. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyoda, T.; Yamasaki, S.; Ueda, S.; Shimizu, K.; Fujii, S.I. Natural Killer T and Natural Killer Cell-Based Immunotherapy Strategies Targeting Cancer. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Si, F.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hoft, D.F.; Peng, G. NK and NKT cells have distinct properties and functions in cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4521–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Ugolini, S.; Blaise, D.; Chabannon, C.; Brossay, L. Targeting natural killer cells and natural killer T cells in cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomel, C.; Jeyarajah, A.; Oram, D.; Shepherd, J.; Milliken, D.; Dauplat, J.; Reynolds, K. Cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Cancer Imaging 2007, 7, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuma, A.E.; Zhang, H.; Gil, L.; Huang, H.; Tsung, A. Surgical Stress Promotes Tumor Progression: A Focus on the Impact of the Immune Response. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, E.; Raz, Y.; Rotkop, G.; Katz, U.; Laskov, I.; Michan, N.; Grisaru, D.; Wolf, I.; Safra, T. Cytoreductive surgery in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A real-world analysis guided by clinical variables, homologous recombination, and BRCA status. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, S.; Lacchetti, C.; Armstrong, D.K.; Cliby, W.A.; Edelson, M.I.; Garcia, A.A.; Ghebre, R.G.; Gressel, G.M.; Lesnock, J.L.; Meyer, L.A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Newly Diagnosed, Advanced Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 868–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuła-Pietrasik, J.; Witucka, A.; Pakuła, M.; Uruski, P.; Begier-Krasińska, B.; Niklas, A.; Tykarski, A.; Książek, K. Comprehensive review on how platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy of ovarian cancer affects biology of normal cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, T.; Ferrero, A.; Sehouli, J.; O’Donnell, D.M.; González-Martín, A.; Joly, F.; van der Velden, J.; Blecharz, P.; Tan, D.S.P.; Querleu, D.; et al. The systemic treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer revisited. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.L.; Eskander, R.N.; O’Malley, D.M. Advances in Ovarian Cancer Care and Unmet Treatment Needs for Patients With Platinum Resistance: A Narrative Review. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, E.C.; McGuire, W.P.; Lin, L.; Temkin, S.M. Radiation Treatment in Women with Ovarian Cancer: Past, Present, and Future. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durno, K.; Powell, M.E. The role of radiotherapy in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwanji, T.P.; Mohindra, P.; Vyfhuis, M.; Snider, J.W., 3rd; Kalavagunta, C.; Mossahebi, S.; Yu, J.; Feigenberg, S.; Badiyan, S.N. Advances in radiotherapy techniques and delivery for non-small cell lung cancer: Benefits of intensity-modulated radiation therapy, proton therapy, and stereotactic body radiation therapy. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2017, 6, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Hormonal maintenance therapy for advance low grade serous ovarian carcinoma appears to be of benefit—That’s a relief! Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 190, A1–A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.M.; Krivak, T.C.; Kabil, N.; Munley, J.; Moore, K.N. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.; Doshi, G.; Godad, A. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Mechanisms, resistance, and the promise of combination therapy. Pathol.—Res. Pract. 2024, 263, 155617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, J.; Bao, Y.; Ao, Q.; Mao, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Gao, J. Bevacizumab in ovarian cancer therapy: Current advances, clinical challenges, and emerging strategies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1589841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previs, R.A.; Sood, A.K.; Mills, G.B.; Westin, S.N. The rise of genomic profiling in ovarian cancer. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2016, 16, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Gao, Q. PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer: Dilemmas and opportunities. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisoni, E.; Morotti, M.; Sarivalasis, A.; Grimm, A.J.; Kandalaft, L.; Laniti, D.D.; Coukos, G. Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer: Towards a tailored immunophenotype-based approach. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musacchio, L.; Cicala, C.M.; Camarda, F.; Ghizzoni, V.; Giudice, E.; Carbone, M.V.; Ricci, C.; Perri, M.T.; Tronconi, F.; Gentile, M.; et al. Combining PARP inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade in ovarian cancer patients: A new perspective on the horizon? ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, R.V.L.; Gupta, R. Exploring the therapeutic use and outcome of antibody-drug conjugates in ovarian cancer treatment. Oncogene 2025, 44, 2343–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, M.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y. Antibody-drug conjugates in gynecologic cancer: Current landscape, clinical data, and emerging targets. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Agrawal, S.K.; Chopra, K. Overcoming drug resistance in ovarian cancer through PI3K/AKT signaling inhibitors. Gene 2025, 948, 149352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, I.C.; Roberts, T.M. Combination of KRAS gene silencing and PI3K inhibition for ovarian cancer treatment. J. Control Release 2020, 318, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, G.A.; Abd Aziz, N.H.; Teik, C.K.; Shafiee, M.N.; Kampan, N.C. New Predictive Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbin, L.M.; Gallion, H.H.; Allison, D.B.; Kolesar, J.M. Next Generation Sequencing and Molecular Biomarkers in Ovarian Cancer-An Opportunity for Targeted Therapy. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borella, F.; Carosso, M.; Chiparo, M.P.; Ferraioli, D.; Bertero, L.; Gallio, N.; Preti, M.; Cusato, J.; Valabrega, G.; Revelli, A.; et al. Oncolytic Viruses in Ovarian Cancer: Where Do We Stand? A Narrative Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, L.L. Five decades of natural killer cell discovery. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20231222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nham, T.; Poznanski, S.M.; Fan, I.Y.; Shenouda, M.M.; Chew, M.V.; Lee, A.J.; Vahedi, F.; Karimi, Y.; Butcher, M.; Lee, D.A.; et al. Ex vivo-expanded NK cells from blood and ascites of ovarian cancer patients are cytotoxic against autologous primary ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, P.; Rabinowich, H.; Crowley-Nowick, P.A.; Bell, M.C.; Mantovani, G.; Whiteside, T.L. Alterations in expression and function of signal-transducing proteins in tumor-associated T and natural killer cells in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 1996, 2, 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, K.; Cook, J.; Park, S.-H.; Topchyan, P.; Kozlowska, A.; Ohanian, N.; Fang, C.; Nishimura, I.; Jewett, A. Novel Strategy to Expand Super-Charged NK Cells with Significant Potential to Lyse and Differentiate Cancer Stem Cells: Differences in NK Expansion and Function between Healthy and Cancer Patients. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konjević, G.M.; Vuletić, A.M.; Mirjačić Martinović, K.M.; Larsen, A.K.; Jurišić, V.B. The role of cytokines in the regulation of NK cells in the tumor environment. Cytokine 2019, 117, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogstad-van Evert, J.S.; Bekkers, R.; Ottevanger, N.; Jansen, J.H.; Massuger, L.; Dolstra, H. Harnessing natural killer cells for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 157, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Matosevic, S. Gene-edited and CAR-NK cells: Opportunities and challenges with engineering of NK cells for immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 27, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, E.; Li, Y.; Yu, L. The Advances and Challenges of NK Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Chen, P.-C.; Ko, M.-W.; Mei, A.; Senjor, E.; Malarkannan, S.; Kos, J.; Jewett, A. Sequential therapy with supercharged NK cells with either chemotherapy drug cisplatin or anti-PD-1 antibody decreases the tumor size and significantly enhances the NK function in Hu-BLT mice. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1132807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Ma, J.; Yue, J.; Lv, R.; Tian, Z.; Fang, F.; Xiao, W. Anti-Tumor Activity of Expanded PBMC-Derived NK Cells by Feeder-Free Protocol in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapdor, R.; Wang, S.; Hacker, U.; Büning, H.; Morgan, M.; Dörk, T.; Hillemanns, P.; Schambach, A. Improved Killing of Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells by Combining a Novel Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Based Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Nie, X. Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of NK cells in the treatment of ovarian cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 51, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.; Chuvin, N.; Valladeau-Guilemond, J.; Depil, S. Development of NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies through receptor engineering. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrén, I.; Orrantia, A.; Astarloa-Pando, G.; Amarilla-Irusta, A.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Borrego, F. Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: From the Basics to Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 884648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, J.W.; Chase, J.M.; Romee, R.; Schneider, S.E.; Sullivan, R.P.; Cooper, M.A.; Fehniger, T.A. Preactivation with IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 induces CD25 and a functional high-affinity IL-2 receptor on human cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2014, 20, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelstein, I.; Mattern, S.; Wang, K.; Haueisen, Y.E.; Greiner, S.M.; Englisch, A.; Staebler, A.; Singer, S.; Lutz, M.S. Preclinical Evaluation of a B7-H3 Targeting Antibody Enhancing NK Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity for Ovarian Cancer Treatment. Immunotargets Ther. 2025, 14, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Topchyan, P.; Jewett, A. Supercharged Natural Killer (sNK) Cells Inhibit Melanoma Tumor Progression and Restore Endogenous NK Cell Function in Humanized BLT Mice. Cancers 2025, 17, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Reese, P.; Chiang, J.; Jewett, A. Natural Killer Cell Therapy Combined with Probiotic Bacteria Supplementation Restores Bone Integrity in Cancer by Promoting IFN-γ Production. Cells 2025, 14, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Topchyan, P.; Kozlowska, A.K.; Ohanian, N.; Chiang, J.; Maung, P.O.; Park, S.-H.; Ko, M.-W.; Fang, C.; Nishimura, I.; et al. Super-charged NK cells inhibit growth and progression of stem-like/poorly differentiated oral tumors in vivo in humanized BLT mice; effect on tumor differentiation and response to chemotherapeutic drugs. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1426518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Ko, M.-W.; Ohanian, N.; Cook, J.; Jewett, A. Osteoclast-expanded super-charged NK-cells preferentially select and expand CD8+ T cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Long, S.; Lin, X.; Yang, A.; Duan, J.; Yang, N.; Yang, Z.; et al. NK cell-derived exosomes enhance the anti-tumor effects against ovarian cancer by delivering cisplatin and reactivating NK cell functions. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1087689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-R.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Lee, D.; Ochoa, C.J.; Singh, T.; DiBernardo, G.; Guo, W.; et al. Overcoming ovarian cancer resistance and evasion to CAR-T cell therapy by harnessing allogeneic CAR-NKT cells. Med. 2025, 6, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, M.; Dinh, K.; Vergara, J.; Birch, G.; Abdulhamid, Y.Z.; Kaplan, I.E.; Ay, O.; Maia, A.; Beaver, O.; Sheffer, M.; et al. CAR memory–like NK cells targeting the membrane proximal domain of mesothelin demonstrate promising activity in ovarian cancer. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn0881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, C.I.; Huang, S.W.; Canoll, P.; Bruce, J.N.; Lin, Y.C.; Pan, C.M.; Lu, H.M.; Chiu, S.C.; Cho, D.Y. Targeting human leukocyte antigen G with chimeric antigen receptors of natural killer cells convert immunosuppression to ablate solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapdor, R.; Wang, S.; Morgan, M.; Dörk, T.; Hacker, U.; Hillemanns, P.; Büning, H.; Schambach, A. Characterization of a Novel Third-Generation Anti-CD24-CAR against Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapdor, R.; Wang, S.; Morgan, M.A.; Zimmermann, K.; Hachenberg, J.; Büning, H.; Dörk, T.; Hillemanns, P.; Schambach, A. NK Cell-Mediated Eradication of Ovarian Cancer Cells with a Novel Chimeric Antigen Receptor Directed against CD44. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hermanson, D.L.; Moriarity, B.S.; Kaufman, D.S. Human iPSC-Derived Natural Killer Cells Engineered with Chimeric Antigen Receptors Enhance Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 181–192.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Liang, B.; Feng, Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, X.; Tian, Y.; et al. Use of chimeric antigen receptor NK-92 cells to target mesothelin in ovarian cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Tan, Y.; Guo, W.; Ao, L.; He, X.; Wu, X.; Xia, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Anti-αFR CAR-engineered NK-92 Cells Display Potent Cytotoxicity Against αFR-positive Ovarian Cancer. J. Immunother. 2019, 42, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heipertz, E.L.; Zynda, E.R.; Stav-Noraas, T.E.; Hungler, A.D.; Boucher, S.E.; Kaur, N.; Vemuri, M.C. Current Perspectives on “Off-The-Shelf” Allogeneic NK and CAR-NK Cell Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 732135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Reyes, R.M.; Zhang, C.; Conejo-Garcia, J.; Curiel, T.J. Targeting Ovarian Cancer with IL-2 Cytokine/Antibody Complexes: A Summary and Recent Advances. J. Cell Immunol. 2021, 3, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, M.A.; Cooley, S.; Judson, P.L.; Ghebre, R.; Carson, L.F.; Argenta, P.A.; Jonson, A.L.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Curtsinger, J.; McKenna, D.; et al. A phase II study of allogeneic natural killer cell therapy to treat patients with recurrent ovarian and breast cancer. Cytotherapy 2011, 13, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Z. Allogenic natural killer cell immunotherapy of sizeable ovarian cancer: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knisely, A.; Rafei, H.; Basar, R.; Banerjee, P.P.; Metwalli, Z.; Lito, K.; Fellman, B.M.; Yuan, Y.; Wolff, R.A.; Morelli, M.P.; et al. Phase I/II study of TROP2 CAR engineered IL15-transduced cord blood-derived NK cells delivered intraperitoneally for the management of platinum resistant ovarian cancer, mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, TPS5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Jiménez-Cortegana, C.; Tay, A.H.M.; Wickström, S.; Galluzzi, L.; Lundqvist, A. NK cells and solid tumors: Therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lundqvist, A. Immunomodulatory Effects of IL-2 and IL-15; Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariya, T.; Hirohashi, Y.; Torigoe, T.; Asano, T.; Kuroda, T.; Yasuda, K.; Mizuuchi, M.; Sonoda, T.; Saito, T.; Sato, N. Prognostic impact of human leukocyte antigen class I expression and association of platinum resistance with immunologic profiles in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, S.; Ferrari de Andrade, L. NKG2D and MICA/B shedding: A ‘tag game’ between NK cells and malignant cells. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greppi, M.; De Franco, F.; Obino, V.; Rebaudi, F.; Goda, R.; Frumento, D.; Vita, G.; Baronti, C.; Melaiu, O.; Bozzo, M.; et al. NK cell receptors in anti-tumor and healthy tissue protection: Mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 270, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, T.; Tian, Y.; Dai, C.; Widarma, C.; Song, R.; Xu, F. Immune checkpoint molecules in natural killer cells as potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Arooj, S.; Wang, H. NK Cell-Based Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, I.; Guillerey, C. Inhibitory Receptors and Immune Checkpoints Regulating Natural Killer Cell Responses to Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.V.; Glukhova, X.A.; Beletsky, I.P.; Ivanov, A.A. NK cell activity in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1609479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Targeted modulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Lai, U.H.; Zhu, L.; Singh, A.; Ahmed, M.; Forsyth, N.R. Reactive Oxygen Species Formation in the Brain at Different Oxygen Levels: The Role of Hypoxia Inducible Factors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.J.; Van Waes, C.; Allen, C.T. Overcoming barriers to effective immunotherapy: MDSCs, TAMs, and Tregs as mediators of the immunosuppressive microenvironment in head and neck cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2016, 58, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Marin, D.; Banerjee, P.; Macapinlac, H.A.; Thompson, P.; Basar, R.; Nassif Kerbauy, L.; Overman, B.; Thall, P.; Kaplan, M.; et al. Use of CAR-Transduced Natural Killer Cells in CD19-Positive Lymphoid Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, P.S.; Suck, G.; Nowakowska, P.; Ullrich, E.; Seifried, E.; Bader, P.; Tonn, T.; Seidl, C. Selection and expansion of natural killer cells for NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygu, B.; Olieslagers, T.I.; Groeneweg, M.; Voorter, C.E.M.; Wieten, L. HLA Class I Molecules as Immune Checkpoints for NK Cell Alloreactivity and Anti-Viral Immunity in Kidney Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 680480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, L.; Vago, L.; Eikema, D.-J.; de Wreede, L.C.; Ciceri, F.; Diaz, M.A.; Locatelli, F.; Jindra, P.; Milone, G.; Diez-Martin, J.L.; et al. Natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation: A study on behalf of the CTIWP of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Guo, C. Crosstalk between macrophages and natural killer cells in the tumor microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101, 108374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, N.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J. NK Cell Therapy: A Rising Star in Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, B.C.; Hsu, K.C. Selection of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant donors to optimize natural killer cell alloreactivity. Semin. Hematol. 2020, 57, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, C.; Na, J.; Tang, J.; Qin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, L. Prospects and limitations of NK cell adoptive therapy in clinical applications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkhi, S.; Zuccolotto, G.; Di Spirito, A.; Rosato, A.; Mortara, L. CAR-NK cell therapy: Promise and challenges in solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1574742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ho, M. CAR NK cell therapy for solid tumors: Potential and challenges. Antib. Ther. 2025, 8, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hao, D.; Qian, H.; Tao, Z. Natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy: From basics to clinical trials. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethacker, L.; Romero, H.; Dulong, J.; Sasseville, M.; Lalonde, M.-E.; Gadoury, C.; Beland, K.; Beausejour, C.; Marcotte, R.; Haddad, E. CRISPR Screens Identify Key Regulators of NK Cell Cytotoxicity in Cancer Therapy. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 0445_5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Arvejeh, P.M.; Bone, S.; Hett, E.; Marincola, F.M.; Roh, K.-H. Nanocarriers for cutting-edge cancer immunotherapies. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Becerril, A.; Aranda-Lara, L.; Isaac-Olivé, K.; Ocampo-García, B.E.; Morales-Ávila, E. Nanocarriers for delivery of siRNA as gene silencing mediator. Excli J. 2022, 21, 1028–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejabi, F.; Abbaszadeh, M.S.; Taji, S.; O’Neill, A.; Farjadian, F.; Doroudian, M. Nanocarriers: A novel strategy for the delivery of CRISPR/Cas systems. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 957572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | T Cells | Natural killer (NK) Cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentages in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) | 40–70% | 5–20% | [126] |

| Major subsets | Helper T cells (CD4+), Cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), Regulatory T cells | Single main type, but with activating and inhibitory receptors | [112,127] |

| Immune System Role | Adaptive immunity | Innate immunity | [112,123] |

| Response Time | Slower (days) | Rapid (hours) | [112,123] |

| Activation | Require antigen presentation via MHC molecules | Do not require prior exposure; detect absence of MHC class I or presence of stress signals | [112,124] |

| Specificity | Highly specific to particular antigens | Broad recognition of stressed, infected, or tumor cells | [112,124] |

| Memory | Generate long-term immunological memory | Limited or conditional | [113,125] |

| Risks of graft vs. host disease in an allogeneic setting | Higher | Lower | [128,129] |

| Characteristics | Natural killer (NK) Cells | Natural killer T (NKT) Cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte type | Large granular lymphocytes (innate immune cells) | Specialized T lymphocytes (subset of T cells) | [135] |

| Percentage in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) | 5–20% | Rare in blood (<1%), enriched in liver and thymus | [136] |

| Gene rearrangement | Do not rearrange TCR genes | Rearrange TCR genes | [136] |

| Key surface marker | CD56 and CD16; lack CD3 | invariant αβ TCR/CD3 | [136] |

| Antigen Recognition | Recognize stress ligands and missing-self signals via activating/inhibitory receptors | Recognize lipid antigens presented by CD1d molecules | [133] |

| Immunity Role | Part of innate immunity; rapid, non-specific cytotoxic response | Bridge innate and adaptive immunity; can rapidly produce cytokines and influence adaptive responses | [130] |

| Cytokine Production | Produce IFN-γ, TNF-α; promote Th1 responses | Produce large amounts of IL-4, IFN-γ, and other cytokines; modulate both Th1 and Th2 responses | [130,132] |

| Memory | No classical memory; short-lived “fight or flight” cells | Some memory-like features due to TCR-mediated activation | [134] |

| Therapy Type | Limitations | How May Natural Killer (NK) Cell Therapy Benefit? | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoreductive surgery | - Falls short in addressing microscopic metastases - High recurrence rate - Can trigger immunosuppression and angiogenesis, supporting tumor growth - Procedure is challenging and has limited efficacy in advanced disease | - NK cells target CSCs, reducing the chances of recurrence - Secreted cytokines support the immune system - Tumor differentiation reduces metastasis and recurrence | [137,138,139] |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy | - High recurrence rates due to drug resistance - Severe side effects (nausea, neuropathy, bone marrow suppression) - Limited efficacy in advanced/recurrent disease - Non-personalized dosing further reduces effectiveness | - Direct killing of resistant tumor cells without relying on DNA damage pathways, potentially reducing recurrence - Minimal or no severe side effects | [140,141,142,143] |

| Localized radiotherapy | - Limited efficacy in advanced/recurrent disease | - Direct killing of resistant tumor cells without relying on DNA damage pathways, potentially reducing recurrence | [144,145,146]. |

| Hormonal therapies | - Resistance develops through adaptations | - Reduced chances of recurrence by targeting CSCs - Tumor differentiation reduces metastasis and recurrence | [147] |

| Targeted Therapy (PARP inhibitors) | - Works mainly in BRCA-mutated or HR-deficient tumors - Resistance develops over time - Not effective for all patients - Long-term use can cause rare but serious toxicities | - NK cells act independently of BRCA/HR status, broadening applicability across patient groups | [148,149] |

| Anti-VEGF therapies | - Limited overall survival (OS) benefits for non-high-risk cases - Resistance emerges from alternative angiogenic pathways - Benefits vary by tumor subtype - Can worsen prognosis in some immune-infiltrated tumors - Risk of hypertension, bleeding, thrombosis, proteinuria, and bowel perforation | - NK cells bypass angiogenesis pathways, directly attacking tumor cells and modulating the immune microenvironment | [150,151] |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | - Limited response rates in ovarian cancer due to the immunosuppressive tumor environment - Tumor immune evasion mechanisms reduce efficacy | - NK cells recognize tumors without antigen priming, overcoming immune evasion and low mutational burden | [152,153] |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors + PARP inhibitors | - Toxicity risks | - Minimal or no severe side effects | [154] |

| Antibody-drug conjugates | - Off-target effects (keratitis, neuropathy, interstitial lung disease) - Limited use due to antigen heterogeneity - Require biomarker-based stratification that restricts eligibility | - Can target heterogeneous tumor population - No biomarker-based stratification is needed | [155,156] |

| Experimental Therapies | - Early-stage, limited clinical data - May face delivery and durability challenges | - NK cells (especially “memory-like” or adaptive NK cells) show persistence and recall ability, enhancing long-term tumor control | [157,158]. |

| NK Cell Activation | Trial Phase | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Patients Enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic CD3/CD19 depleted NK+ IL-2 | Completed | NCT01105650 | 13 |

| Allogeneic NK+ IL-12 | Terminated | NCT00652899 | 12 |

| Haploidentical NK+IL-2 + indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase | Completed | NCT02118285 | 2 |

| Allogeneic NK + IL-2 | Completed | NCT03213964 | 10 |

| Cryosurgery + NK | Completed | NCT02849353 | 30 |

| TROP2-CAR IL-15 transduced cord blood-NK | Phase 2 | NCT05922930 | 51 |

| Anti-mesothelin CAR-NK | Phase 1 | NCT03692637 | 30 |

| Autologous activated NK | Phase 2 | NCT03634501 | 200 |

| Ex vivo-generated UCB-derived allogeneic NK + IL-2 | Completed | NCT03539406 | 11 |

| Cytokine-induced NK cells + Radiofrequency ablation | Phase 2 | NCT02487693 | 50 |

| Cytokine (IL-2)-induced memory-like NK | Phase 1 | NCT06321484 | 18 |

| NKG2D CAR-NK | Unknown | NCT05776355 | 18 |

| NKT | Phase 1 | NCT06586957 | 150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaur, K. Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Therapies Have the Potential to Treat Ovarian Cancer Effectively by Targeting Diverse Tumor Populations and Reducing the Risk of Recurrence. Cancers 2025, 17, 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233862

Kaur K. Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Therapies Have the Potential to Treat Ovarian Cancer Effectively by Targeting Diverse Tumor Populations and Reducing the Risk of Recurrence. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233862

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaur, Kawaljit. 2025. "Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Therapies Have the Potential to Treat Ovarian Cancer Effectively by Targeting Diverse Tumor Populations and Reducing the Risk of Recurrence" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233862

APA StyleKaur, K. (2025). Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Therapies Have the Potential to Treat Ovarian Cancer Effectively by Targeting Diverse Tumor Populations and Reducing the Risk of Recurrence. Cancers, 17(23), 3862. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233862