From Fibrosis to Malignancy: Mechanistic Intersections Driving Lung Cancer Progression

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

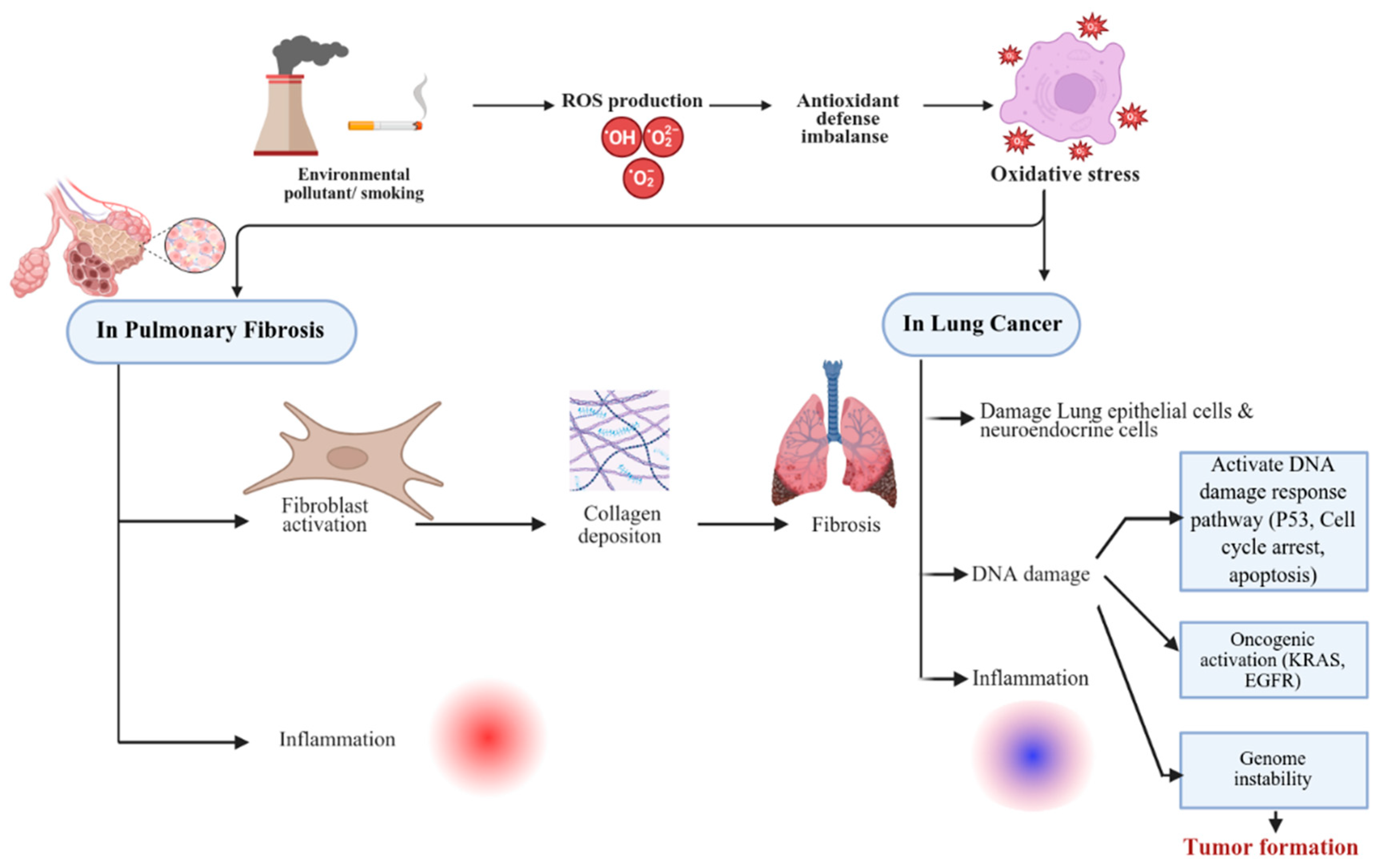

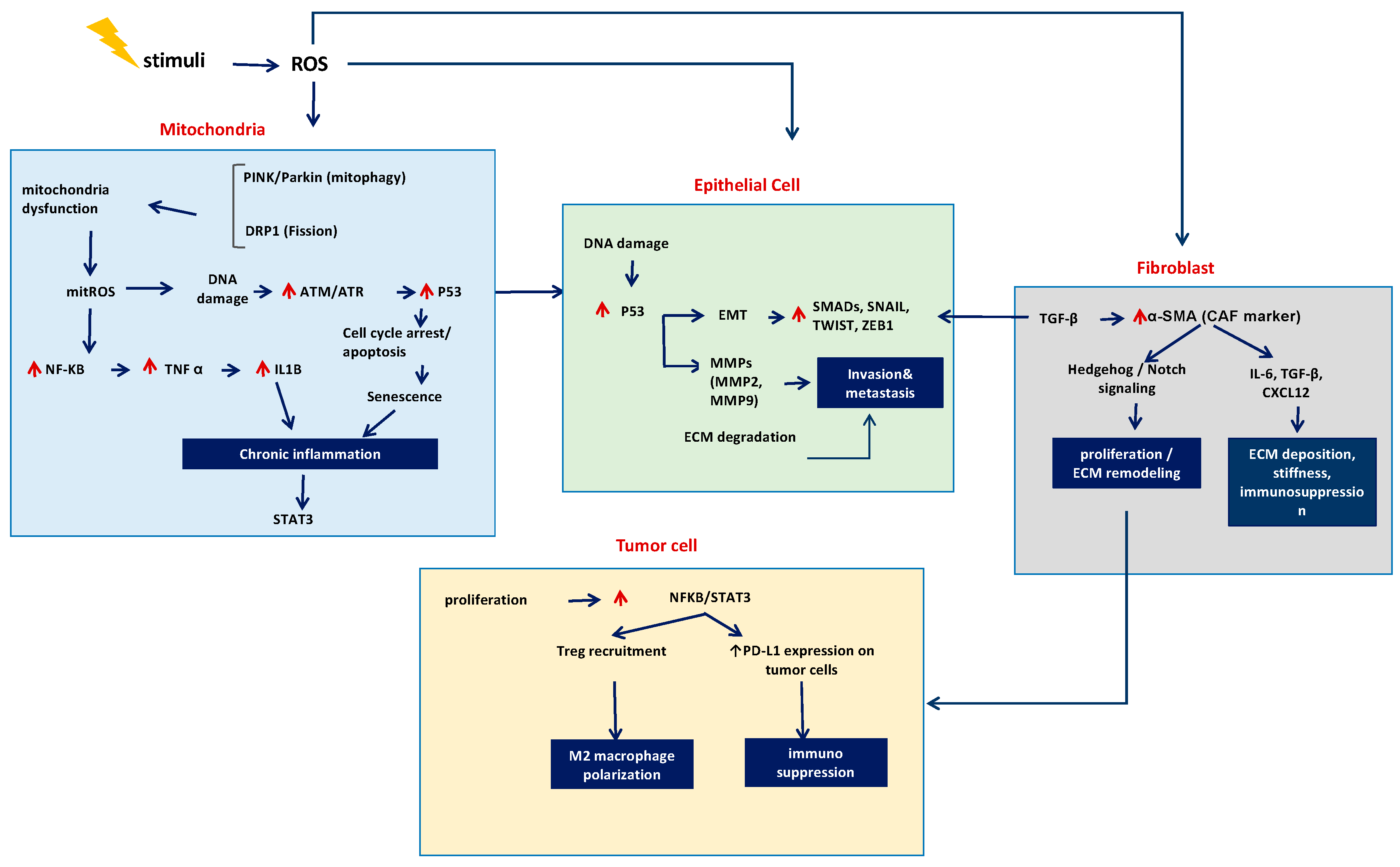

2. Oxidative Stress, DNA Damage, and Repair

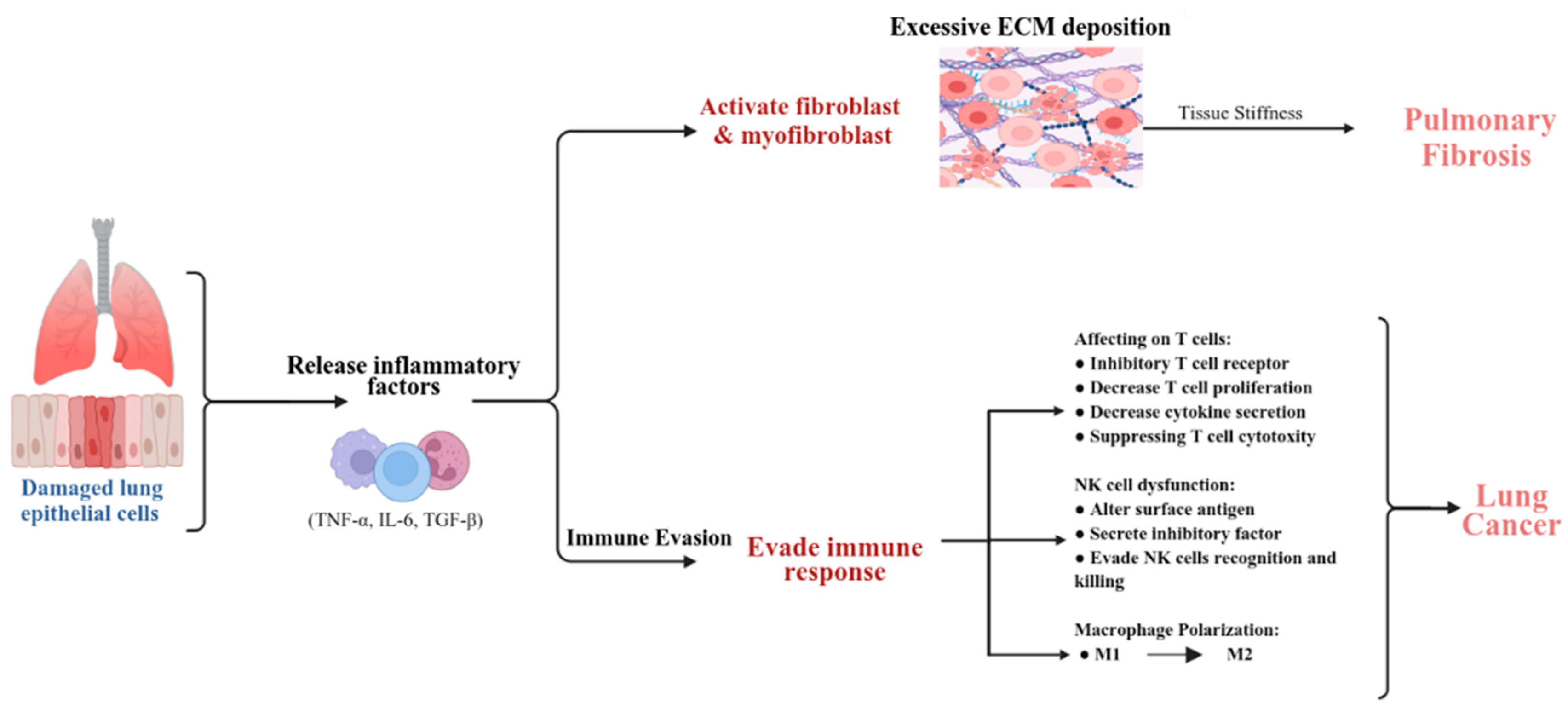

3. Immune Responses and Microenvironment

4. Cell Activation, Proliferation, Cell Cycle, and Anti-Apoptotic Mechanisms

5. Mitochondrial Metabolism

6. The Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in LC and PF

7. Biomarkers in Lung Fibrosis and Lung Cancer

8. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, N.; Wang, B.; Tan, K.; Fan, Y.; Cao, P. Glycolysis and beyond in glucose metabolism: Exploring pulmonary fibrosis at the metabolic crossroads. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1379521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, T.M.; Bendstrup, E.; Dron, L.; Langley, J.; Smith, G.; Khalid, J.M.; Patel, H.; Kreuter, M. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, K. Lung Cancer: Understanding Its Molecular Pathology and the 2015 WHO Classification. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Chang, J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.T.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, H.I. The relationship between the severity of pulmonary fibrosis and the lung cancer stage. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 2807–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandra, K.C.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Aluru, J.S.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Contemp. Oncol. 2021, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, P.M.; Wu, C.C.; Carter, B.W.; Munden, R.F. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżak, B.; Majewski, S. Concomitant Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer: An Updated Narrative Review. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Totero, D.; Barisione, E.; Clini, E. Editorial: Pulmonary fibrosis and lung carcinogenesis: Do myofibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts share a common identity? Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1389532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Qubo, A.; Numan, J.; Snijder, J.; Padilla, M.; Austin, J.H.M.; Capaccione, K.M.; Pernia, M.; Bustamante, J.; O’Connor, T.; Salvatore, M.M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: Future directions and challenges. Breathe 2022, 18, 220147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, R.R.; Tareq, F.S.; Yildiz, E.; Luthria, D.L. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants—A Critical Review on In Vitro Antioxidant Assays. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Gomatou, G.; Bouros, E.; Trigidou, R.; Tzilas, V.; Bouros, D. Common Pathogenic Mechanisms Between Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. Chest 2019, 156, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.P.; Lewis, C.; Thomas, P.S. Oxidative stress and exhaled breath analysis: A promising tool for detection of lung cancer. Cancers 2010, 2, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.B.; Thannickal, V.J.; Toews, G.B. Bone Marrow-Derived Cells in the Pathogenesis of Lung Fibrosis. Curr. Respir. Med. Rev. 2005, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, N.; Sakai, S.; Kitagawa, M. Molecular Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis, with Focus on Pathways Related to TGF-beta and the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Guan, X.; Bao, G.; Yao, Y.; Zhong, X. Molecular subtyping of small cell lung cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86 Pt 2, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz de Aja, J.; Dost, A.F.M.; Kim, C.F. Alveolar progenitor cells and the origin of lung cancer. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 289, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, V.M.L.; Carvalho, L. Heterogeneity in Lung Cancer. Pathobiology 2018, 85, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Signaling pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 7038–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, U.S.; Tan, B.W.Q.; Vellayappan, B.A.; Jeyasekharan, A.D. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019, 25, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannunzio, N.R.; Watanabe, G.; Lieber, M.R. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10512–10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Ling, H.; Huang, Y.; Dong, H.; Xie, B.; Hao, Q.; Zhou, X. AZD1775 synergizes with SLC7A11 inhibition to promote ferroptosis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Jia, K.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; He, Y.; Zhou, C. Alterations of DNA damage response pathway: Biomarker and therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y. Phase separation in DNA damage response: New insights into cancer development and therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, A.; Maji, A.; Potdar, P.D.; Singh, N.; Parikh, P.; Bisht, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Paul, M.K. Lung cancer immunotherapy: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zimmerman, S.E.; Weyemi, U. Genomic instability and metabolism in cancer. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 364, 241–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gniadecki, R.; Iyer, A.; Hennessey, D.; Khan, L.; O’Keefe, S.; Redmond, D.; Storek, J.; Durand, C.; Cohen-Tervaert, J.W.; Osman, M. Genomic instability in early systemic sclerosis. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 131, 102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, J.; Chand, A.; Gough, D.; Ernst, M. Therapeutically exploiting STAT3 activity in cancer—Using tissue repair as a road map. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, S.M.; Choi, A.M. Mitochondria in lung disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.M.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Schwarz, M.I.; Lynch, D.; Kurche, J.; Warg, L.; Yang, I.V.; Schwartz, D.A. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Genetic Disease That Involves Mucociliary Dysfunction of the Peripheral Airways. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1567–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armanios, M.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Cogan, J.D.; Alder, J.K.; Ingersoll, R.G.; Markin, C.; Lawson, W.E.; Xie, M.; Vulto, I.; Phillips, J.A., III; et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.T.; Felip, E.; Bauer, T.M.; Besse, B.; Navarro, A.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Gainor, J.F.; Johnson, M.; Dietrich, J.; James, L.P.; et al. Lorlatinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with ALK or ROS1 rearrangement: An international, multicentre, open-label, single-arm first-in-man phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddireddy, V.; Siva Prasad, B.; Gundimeda, S.D.; Penagaluru, P.R.; Mundluru, H.P. Assessment of 8-oxo-7, 8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine and malondialdehyde levels as oxidative stress markers and antioxidant status in non-small cell lung cancer. Biomarkers 2012, 17, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estornut, C.; Milara, J.; Bayarri, M.A.; Belhadj, N.; Cortijo, J. Targeting Oxidative Stress as a Therapeutic Approach for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 794997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanan, A.; Washimkar, K.R.; Mugale, M.N. Unraveling the interplay between vital organelle stress and oxidative stress in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-C. Natural plant resource flavonoids as potential therapeutic drugs for pulmonary fibrosis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Pu, W.; Chen, L.; Guo, D.; Jiang, H.; He, B.; Qin, S.; Wang, K.; Li, N.; et al. Cancer metabolism and tumor microenvironment: Fostering each other? Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 236–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Ramalingam, T.R. Mechanisms of fibrosis: Therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Su, L.; Deng, C.; Huang, J.; Chen, G. Incomplete Knockdown of MyD88 Inhibits LPS-Induced Lung Injury and Lung Fibrosis in a Mouse Model. Inflammation 2023, 46, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Qu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S. Iguratimod decreases bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in association with inhibition of TNF-alpha in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Karmouty-Quintana, H.; Melicoff, E.; Le, T.T.; Weng, T.; Chen, N.Y.; Pedroza, M.; Zhou, Y.; Davies, J.; Philip, K.; et al. Blockade of IL-6 Trans signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3755–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qin, W.; Liang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, W. Bufei huoxue capsule alleviates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice via TGF-beta1/Smad2/3 signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 316, 116733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sharma, A.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.H. Evolving insights into the improvement of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy through PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in the clinical spectrum of lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, W.J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Q. Regulatory mechanisms of immune checkpoints PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Arooj, S.; Wang, H. NK Cell-Based Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Ju, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tumor microenvironment remodeling and tumor therapy based on M2-like tumor associated macrophage-targeting nano-complexes. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2892–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevach, E.M.; Thornton, A.M. tTregs, pTregs, and iTregs: Similarities and differences. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 259, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.Y.; Das, J.; Prendergast, C.; De Jong, D.; Braumuller, B.; Paily, J.; Huang, S.; Liou, C.; Giarratana, A.; Hosseini, M.; et al. Advances in CAR T Cell Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 9019–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Luo, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Bian, H.; Chen, Z. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell targeting EGFRvIII for metastatic lung cancer therapy. Front. Med. 2019, 13, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Karschnia, P.; Cadilha, B.L.; Dede, S.; Lorenz, M.; Seewaldt, N.; Nikolaishvili, E.; Muller, K.; Blobner, J.; Teske, N.; et al. In vivo dynamics and anti-tumor effects of EpCAM-directed CAR T-cells against brain metastases from lung cancer. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2163781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouac, J.; Cauvet, A.; Orvain, C.; Boulch, M.; Tilotta, F.; Tu, L.; Thuillet, R.; Ottaviani, M.; Guignabert, C.; Bousso, P.; et al. Effects of B Cell Depletion by CD19-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in a Murine Model of Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocarro, L.; Arasanz, H.; Fernandez-Rubio, L.; Blanco, E.; Echaide, M.; Bocanegra, A.; Teijeira, L.; Garnica, M.; Morilla, I.; Martinez-Aguillo, M.; et al. CAR-T Cells for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Life 2022, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Furlan, S.N.; Jaeger-Ruckstuhl, C.A.; Sarvothama, M.; Berger, C.; Smythe, K.S.; Garrison, S.M.; Specht, J.M.; Lee, S.M.; Amezquita, R.A.; et al. Immunogenic Chemotherapy Enhances Recruitment of CAR-T Cells to Lung Tumors and Improves Antitumor Efficacy when Combined with Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 193–208.e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kythreotou, A.; Siddique, A.; Mauri, F.A.; Bower, M.; Pinato, D.J. PD-L1. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 71, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, L.M.; Sage, P.T.; Sharpe, A.H. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 236, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, M.; Yang, Y.; Yao, C.; He, S.; Duan, H.; Xia, W.; Sun, R.; Yao, Y.; et al. Peripheral CD4+ T cell signatures in predicting the responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy for Chinese advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021, 64, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernacka, A.; Dobaczewski, M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors 2011, 29, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazono, K.; Ehata, S.; Koinuma, D. Tumor-promoting functions of transforming growth factor-β in progression of cancer. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2012, 117, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, D.M.; Moretti, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Cooper, S.W.; Chambers, D.M.; Santangelo, P.J.; Barker, T.H. LEM domain-containing protein 3 antagonizes TGFbeta-SMAD2/3 signaling in a stiffness-dependent manner in both the nucleus and cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15867–15886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.H.; Ritzenthaler, J.D.; Roman, J. Lung extracellular matrix and redox regulation. Redox Biol. 2016, 8, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, J.; Henke, C.A.; Bitterman, P.B. Extracellular matrix as a driver of progressive fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, J.H.; Karsdal Ma Genovese, F.; Johnson, S.; Svensson, B.; Jacobsen, S.; Hägglund, P.; Leeming, D.J. The role of extracellular matrix quality in pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 88, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, G.E.; Akim, A.M.; Sung, Y.Y.; Muhammad, T.S.T. Cancer and Apoptosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2543, 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, M.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K. Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and degradation as cancer drivers. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Qiu, L.; Yue, J.; Si, J.; Zhang, H. The metabolic crosstalk of cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor cells: Recent advances and future perspectives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Che, G. Advancement of relationship between metabolic alteration in cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor progression in lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 2014, 17, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Cheng, X.; Rong, R.; Gao, Y.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y. High expression of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) predicts poor outcome in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, J.S.; Nobre, A.R.; Mondal, C.; Taha, I.; Farias, E.F.; Fertig, E.J.; Naba, A.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J. A tumor-derived type III collagen-rich ECM niche regulates tumor cell dormancy. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Tian, J.; Fan, Y.; Cao, P. Latest progress on the molecular mechanisms of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 9811–9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dai, S.D.; Han, Y.; Wang, E.H. Dishevelled-1 and dishevelled-3 affect cell invasion mainly through canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathway, respectively, and associate with poor prognosis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2010, 49, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, F.; Rahmani, A.H.; Prabhu, S.V.; Kumar, V.; Anwar, S. The Role of Plant-Derived Natural Products as a Regulator of the Tyrosine Kinase Pathway in the Management of Lung Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ningthoujam, R.; Chanu, N.B.; Anumala, V.; Babu, P.J.; Pradhan, S.; Panda, M.K.; Heisnam, P.; Singh, Y.D. Predicting Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Stud. Comput. Intell. 2022, 1016, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Buachan, P.; Namsa-Aid, M.; Sung, H.K.; Peng, C.; Sweeney, G.; Tanechpongtamb, W. Inhibitory effects of terrein on lung cancer cell metastasis and angiogenesis. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Geletu, M.; Arulanandam, R.; Raptis, L. Stat3 and gap junctions in normal and lung cancer cells. Cancers 2014, 6, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.H.; Huang, K.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, H.Y.; Hsueh, C.; Liu, Y.T.; Yang, S.C.; Yang, P.C.; Chen, C.Y. PM2.5 promotes lung cancer progression through activation of the AhR-TMPRSS2-IL18 pathway. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, J.; Yasuda, H.; Nonaka, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Soejima, K.; Betsuyaku, T. The FGF2 aptamer inhibits the growth of FGF2-FGFR pathway driven lung cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Iqbal, N. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) in Cancers: Overexpression and Therapeutic Implications. Mol. Biol. Int. 2014, 2014, 852748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, J.; Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, C.; Yang, L. CDK4/6 inhibitors in lung cancer: Current practice and future directions. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 230145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mender, I.; LaRanger, R.; Luitel, K.; Peyton, M.; Girard, L.; Lai, T.P.; Batten, K.; Cornelius, C.; Dalvi, M.P.; Ramirez, M.; et al. Telomerase-Mediated Strategy for Overcoming Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Targeted Therapy and Chemotherapy Resistance. Neoplasia 2018, 20, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Cheng, J.; Pang, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Yuan, Z.; Qian, D. BIBR1532, a Selective Telomerase Inhibitor, Enhances Radiosensitivity of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Through Increasing Telomere Dysfunction and ATM/CHK1 Inhibition. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 105, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, O.; Zer, A.; Yosef, L.; Beery, E.; Goldvaser, H.; Gutkin, A.; Levin, R.; Dudnik, E.; Berger, T.; Feinmesser, M.; et al. Blood-Derived Exosomal hTERT mRNA in Patients with Lung Cancer: Characterization and Correlation with Response to Therapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vitis, M.; Berardinelli, F.; Sgura, A. Telomere Length Maintenance in Cancer: At the Crossroad between Telomerase and Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guterres, A.N.; Villanueva, J. Targeting telomerase for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5811–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ullenbruch, M.; Young Choi, Y.; Yu, H.; Ding, L.; Xaubet, A.; Pereda, J.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A.; Bitterman, P.B.; Henke, C.A.; et al. Telomerase and telomere length in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Batenburg, A.A.; Kazemier, K.M.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; van der Vis, J.J.; Grutters, J.C.; Goldschmeding, R.; van Moorsel, C.H.M. Telomere shortening and DNA damage in culprit cells of different types of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00691-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arish, N.; Petukhov, D.; Wallach-Dayan, S.B. The Role of Telomerase and Telomeres in Interstitial Lung Diseases: From Molecules to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, K.; Hua, F.; Cui, B.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; et al. The cell cycle inhibitor P21 promotes the development of pulmonary fibrosis by suppressing lung alveolar regeneration. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzina, I.G.; Rus, V.; Lockatell, V.; Courneya, J.P.; Hampton, B.S.; Fishelevich, R.; Misharin, A.V.; Todd, N.W.; Badea, T.C.; Rus, H.; et al. Regulator of Cell Cycle Protein (RGCC/RGC-32) Protects against Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 66, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Qi, L.; Zhang, S.; Bi, Y.; Yu, Y. SOX6 suppresses the development of lung adenocarcinoma by regulating expression of p53, p21(CIPI), cyclin D1 and beta-catenin. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ren, D.; Liu, H.; Kang, C.; Chen, J. HOTAIR, a long noncoding RNA, is a marker of abnormal cell cycle regulation in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 2717–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, T.; Tong, P.; Diao, L.; Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Hoff, J.; Heymach, J.V.; Wang, J.; Byers, L.A. Targeting AXL and mTOR Pathway Overcomes Primary and Acquired Resistance to WEE1 Inhibition in Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6239–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, K.; Tanimoto, A.; Della Corte, C.M.; Stewart, C.A.; Wang, Q.; Shen, L.; Cardnell, R.J.; Wang, J.; Polanska, U.M.; Andersen, C.; et al. Targeting BCL2 Overcomes Resistance and Augments Response to Aurora Kinase B Inhibition by AZD2811 in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 3237–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, L.; Durante, M.; Lanzi, C.; Pini, A.; Boccalini, G.; Calosi, L.; Moroni, F.; Masini, E.; Mannaioni, G. HYDAMTIQ, a selective PARP-1 inhibitor, improves bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis by dampening the TGF-beta/SMAD signalling pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.; Burgess, J.T.; O’Byrne, K.; Richard, D.J.; Bolderson, E. PARP Inhibitors: Clinical Relevance, Mechanisms of Action and Tumor Resistance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 564601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachimatla, A.G.; Fenstermaker, R.; Ciesielski, M.; Yendamuri, S. Survivin in lung cancer: A potential target for therapy and prevention-a narrative review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, D.; Otoupalova, E.; Smith, S.R.; Volckaert, T.; De Langhe, S.P.; Thannickal, V.J. Developmental pathways in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 65, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ArulJothi, K.N.; Kumaran, K.; Senthil, S.; Nidhu, A.B.; Munaff, N.; Janitri, V.B.; Kirubakaran, R.; Singh, S.K.; Gupt, G.; Dua, K.; et al. Implications of reactive oxygen species in lung cancer and exploiting it for therapeutic interventions. Med. Oncol. 2022, 40, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadov, S. Mitochondria and ferroptosis. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2022, 25, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; He, W.; Yang, L.-L. Revitalizing antitumor immunity: Leveraging nucleic acid sensors as therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2024, 588, 216729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; He, R.; Liu, B.; Jiang, W.; Wang, B.; Li, N.; Geng, Q. Ferroptosis: A New Promising Target for Lung Cancer Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 8457521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Feng, D.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Tang, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, X.; Yue, S.; Li, C.; Luo, Z. Iron deposition-induced ferroptosis in alveolar type II cells promotes the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, W.; Song, J.; Wei, S.; Xia, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Li, E.; Ren, C.; et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4-dependent glutathione high-consumption drives acquired platinum chemoresistance in lung cancer-derived brain metastasis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Xiao, H.; Luo, T.; Lin, H.; Deng, J. Role of Ferroptosis in Regulating the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.T.; Zhang, X.Y.; Cao, R.; Sun, L.; Jing, W.; Zhao, J.Z.; Zhang, S.L.; Huang, L.T.; Han, C.B. Effects of Dynamin-related Protein 1 Regulated Mitochondrial Dynamic Changes on Invasion and Metastasis of Lung Cancer Cells. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 4045–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiyama, A.; Okamoto, K. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, W.; Hu, S.; Lyu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wei, T.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J. METTL3 promotes chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer by inducing mitophagy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsubouchi, K.; Araya, J.; Kuwano, K. PINK1-PARK2-mediated mitophagy in COPD and IPF pathogeneses. Inflamm. Regen. 2018, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Chang, J.; Li, D.; Cao, P. Iron overload and mitochondrial dysfunction orchestrate pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 912, 174613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Lai, Y.C.; Romero, Y.; Brands, J.; St Croix, C.M.; Kamga, C.; Corey, C.; Herazo-Maya, J.D.; Sembrat, J.; Lee, J.S.; et al. PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H.; Budinger, G.R.; Mutlu, G.M.; Jain, M. Proteasomal regulation of pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhu, C.W.; Ali, A.A. Dysregulation of the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Human Malignancies: A Window for Therapeutic Intervention. Cancers 2021, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Ni, D.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, Y.; Gao, M.; Shi, W.; Song, J.; et al. Over-expression of USP15/MMP3 predict poor prognosis and promote growth, migration in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Genet. 2023, 272–273, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Hu, T.; Song, G. Knocking down USP39 Inhibits the Growth and Metastasis of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells through Activating the p53 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkedy, D.; Gonen, H.; Bercovich, B.; Ciechanover, A. Complete reconstitution of conjugation and subsequent degradation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by purified components of the ubiquitin proteolytic system. FEBS Lett. 1994, 348, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Park, W.H. MG132 as a proteasome inhibitor induces cell growth inhibition and cell death in A549 lung cancer cells via influencing reactive oxygen species and GSH level. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semren, N.; Welk, V.; Korfei, M.; Keller, I.E.; Fernandez, I.E.; Adler, H.; Gunther, A.; Eickelberg, O.; Meiners, S. Regulation of 26S Proteasome Activity in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semren, N.; Habel-Ungewitter, N.C.; Fernandez, I.E.; Konigshoff, M.; Eickelberg, O.; Stoger, T.; Meiners, S. Validation of the 2nd Generation Proteasome Inhibitor Oprozomib for Local Therapy of Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.L.; Ciechanover, A. Targeting proteins for destruction by the ubiquitin system: Implications for human pathobiology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2009, 49, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasotiriou, I.; Parsonidis, P.; Ntanovasilis, D.-A.; Iliopoulos, A.C.; Beis, G.; Apostolou, P. Identification of new targets and biomarkers in lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, e14656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.E.; Rajapaksa, Y.; Keshavjee, S.; Liu, M. Applications of transcriptomics in ischemia reperfusion research in lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, X.; Qu, C.; Xu, S. Predictive Value of Gene Databases in Discovering New Biomarkers and New Therapeutic Targets in Lung Cancer. Medicina 2023, 59, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Konig, M.F.; Pardoll, D.M.; Bettegowda, C.; Papadopoulos, N.; Wright, K.M.; Gabelli, S.B.; Ho, M.; van Elsas, A.; Zhou, S. Cancer therapy with antibodies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.C.; Mehmood, A.; Wei, D.-Q.; Dai, X. Systems Biology Integration and Screening of Reliable Prognostic Markers to Create Synergies in the Control of Lung Cancer Patients. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agnano, V.; Mariniello, D.F.; Ruotolo, M.; Quarcio, G.; Moriello, A.; Conte, S.; Sorrentino, A.; Sanduzzi Zamparelli, S.; Bianco, A.; Perrotta, F. Targeting Progression in Pulmonary Fibrosis: An Overview of Underlying Mechanisms, Molecular Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Intervention. Life 2024, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Goyal, A.; Ilma, B.; Rekha, M.M.; Nayak, P.P.; Kaur, M.; Khachi, A.; Goyal, K.; Rana, M.; Rekha, A.; et al. Exosomal miRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in silicosis-related lung fibrosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moog, M.; Aschenbrenner, F.; Jonigk, D.; Prinz, I.; Welte, T.; Kolb, M.; Maus, U.A. Role of IL17 A/F in experimental lung fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, Z.; Atkinson, E.J.; Carmona, E.M.; White, T.A.; Heeren, A.A.; Jachim, S.K.; Zhang, X.; Cummings, S.R.; Chiarella, S.E.; Limper, A.H.; et al. Biomarkers of cellular senescence in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlund, C.J.E.; Eklund, A.; Grunewald, J.; Gabrielsson, S. Pulmonary Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Local and Systemic Inflammation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, F.; Zheng, D.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Huang, X. FGF/FGFR signaling: From lung development to respiratory diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 62, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoaga, O.; Braicu, C.; Jurj, A.; Rusu, A.; Buiga, R.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Progress in Research on the Role of Flavonoids in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, V.; Ramchandran, R.; Kamp, D.W.; Natarajan, V. Lipid Mediators Regulate Pulmonary Fibrosis: Potential Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Dong, Y.; Yang, X.; Mo, L.; You, Y. Crosstalk between lncRNAs and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in lung cancers: From cancer progression to therapeutic response. Non-Coding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Ren, T. Senescent lung fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis facilitate non-small cell lung cancer progression by secreting exosomal MMP1. Oncogene 2024, 44, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.-P.; Zeng, M.; He, X. Role of sphingolipids signaling in pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Chin. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, K.; Jia, C.; Hou, Y.; Bai, G. Astragaloside IV protects against lung injury and pulmonary fibrosis in COPD by targeting GTP-GDP domain of RAS and downregulating the RAS/RAF/FoxO signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, R.; Maddipatla, V.; Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, O.; Hose, S.; Zigler, J.S.; Sinha, D.; Liu, H. Aberrant Akt2 signaling in the RPE may contribute to retinal fibrosis process in diabetic retinopathy. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anajafi, S.; Hadavi, R.; Valizadeh-Otaghsara, S.M.; Hemmati, M.; Hassani, M.; Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S.; Soleimani, M. A functional interplay between non-coding RNAs and cancer-associated fibroblasts in breast cancer. Gene Rep. 2024, 36, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmer, N.K.; Choudhury, M.; Mirza, H.; Pradhan, S.; Yin, Y.; Mecham, R.P.; Brody, S.L.; Ornitz, D.M.; Koenitzer, J.R. Latent transforming growth factor binding protein-2 (LTBP2), an IPF biomarker of clinical decline, promotes TGF-beta signaling and lung fibrosis in mice. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zuo, Q.; Zou, J. Anoikis and SPP1 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Integrating bioinformatics, cell, and animal studies to explore prognostic biomarkers and PI3K/AKT signaling regulation. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Hamdy, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, P.; Fu, Y.; Shen, J. From Fibrosis to Malignancy: Mechanistic Intersections Driving Lung Cancer Progression. Cancers 2025, 17, 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233861

Chen B, Hamdy H, Zhang X, Cao P, Fu Y, Shen J. From Fibrosis to Malignancy: Mechanistic Intersections Driving Lung Cancer Progression. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233861

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bing, Hayam Hamdy, Xu Zhang, Pengxiu Cao, Yi Fu, and Junling Shen. 2025. "From Fibrosis to Malignancy: Mechanistic Intersections Driving Lung Cancer Progression" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233861

APA StyleChen, B., Hamdy, H., Zhang, X., Cao, P., Fu, Y., & Shen, J. (2025). From Fibrosis to Malignancy: Mechanistic Intersections Driving Lung Cancer Progression. Cancers, 17(23), 3861. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233861