Minimally Invasive Resection of Occult Insulinomas—Experience from an ENETS Centre of Excellence and Review of the Literature

Simple Summary

Abstract

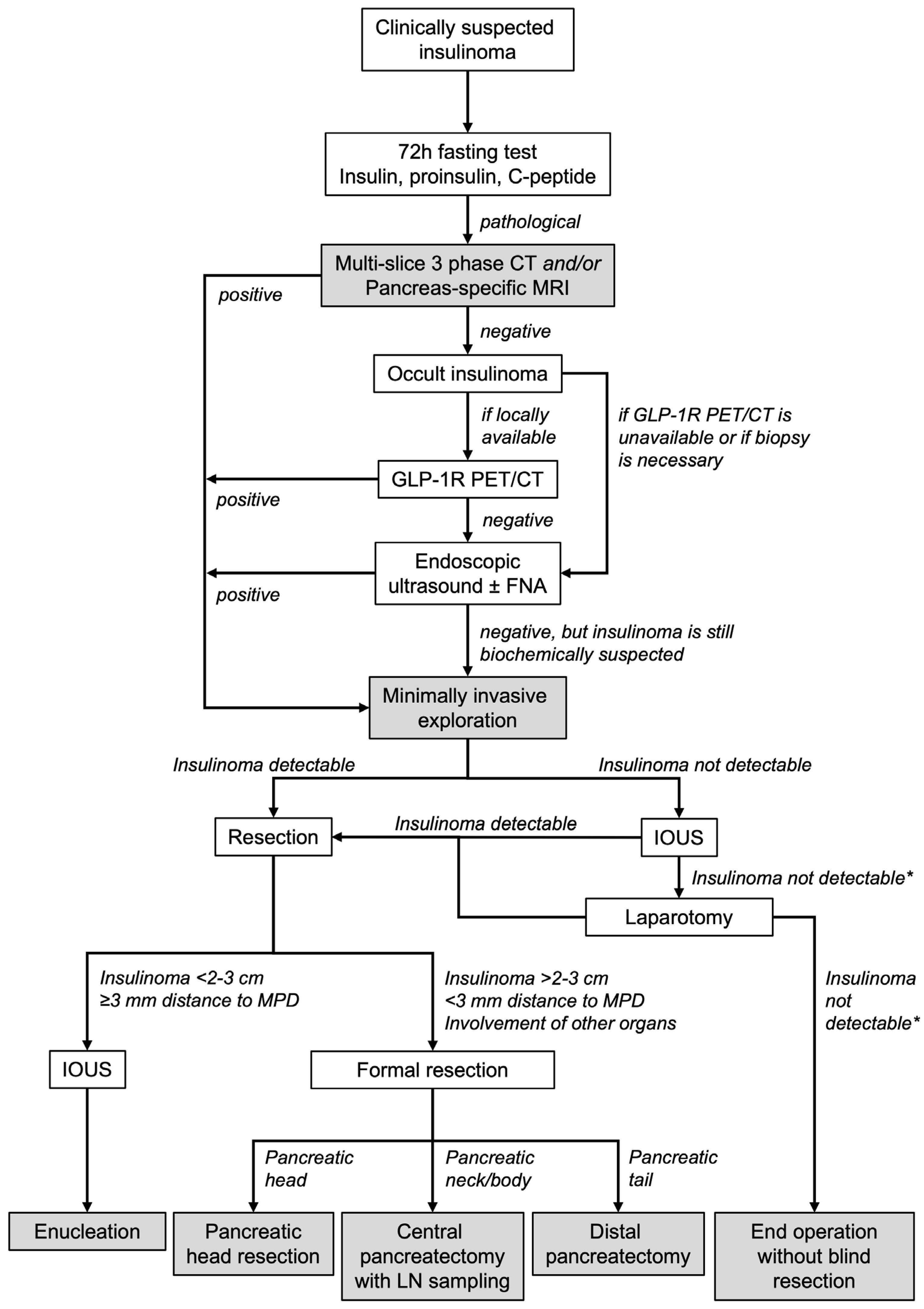

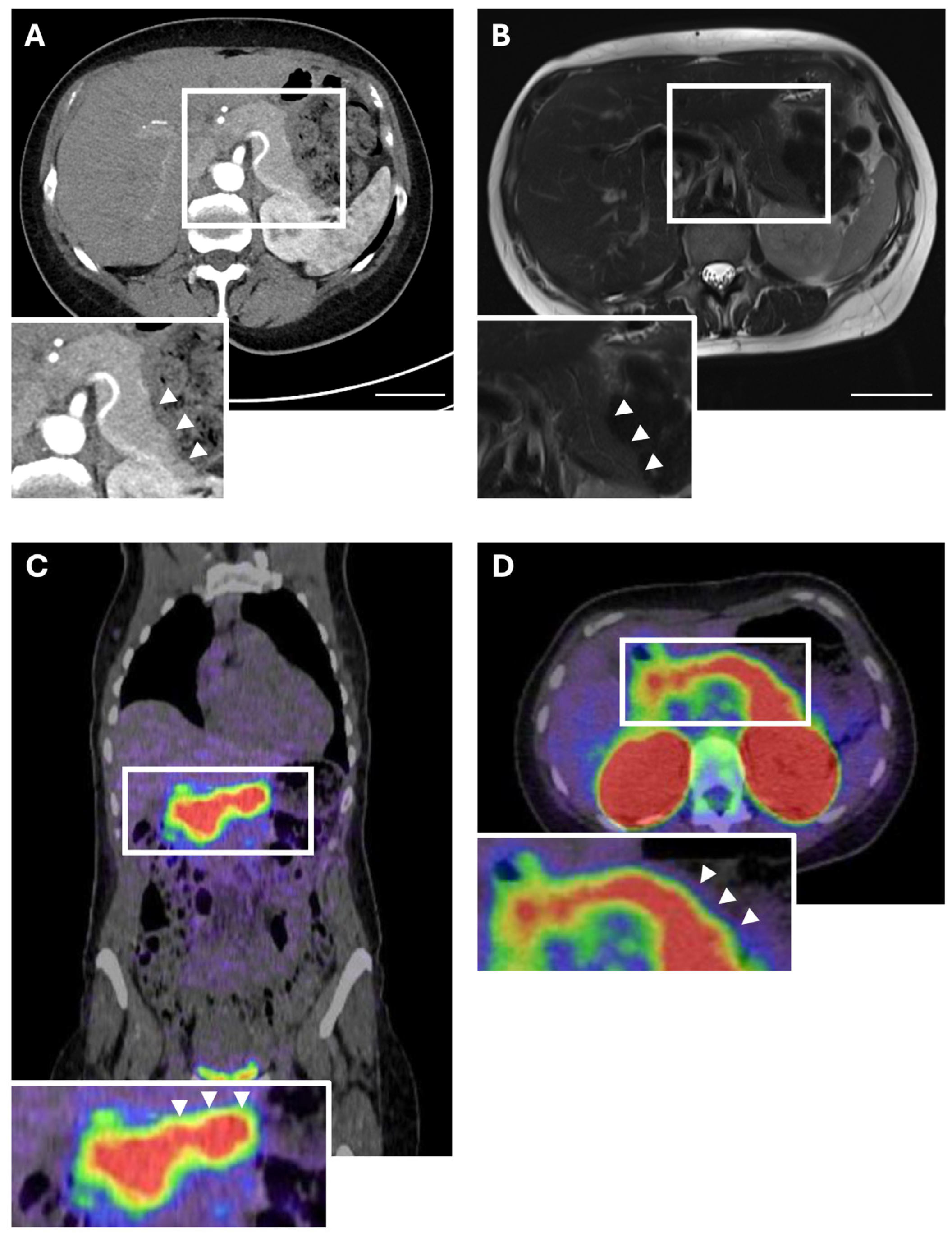

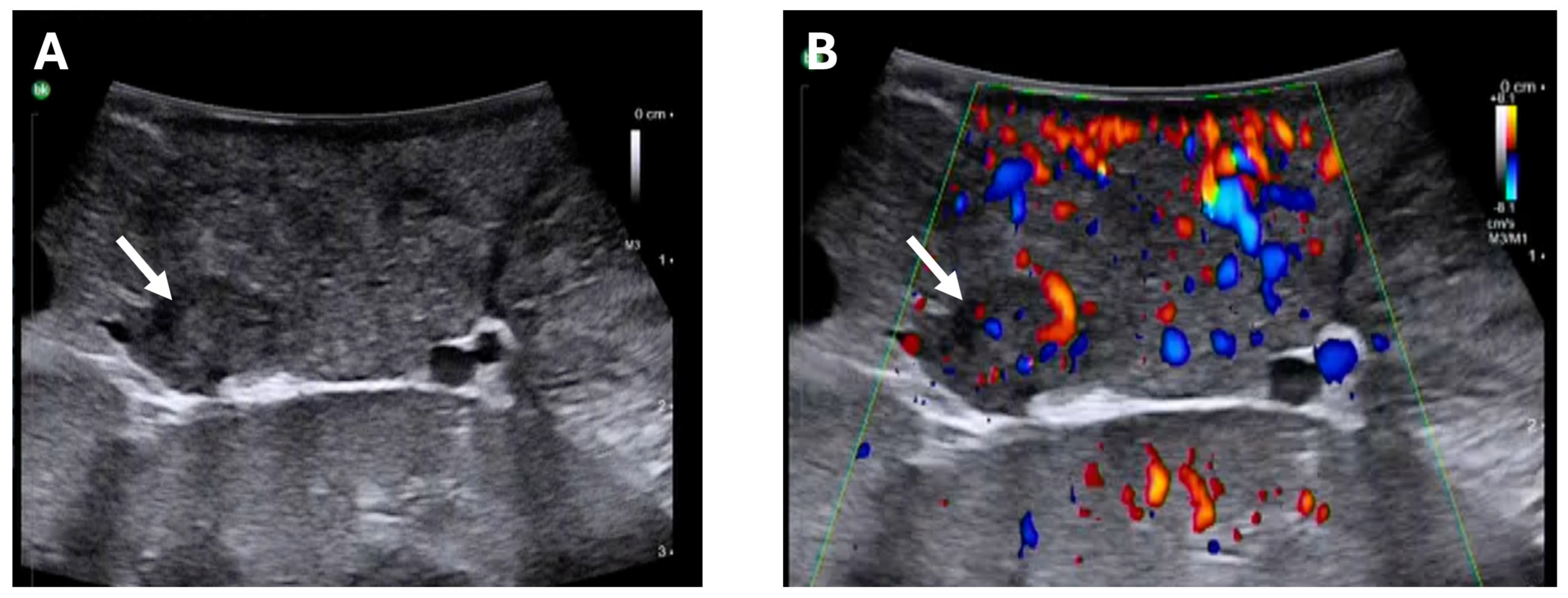

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Clinical Data

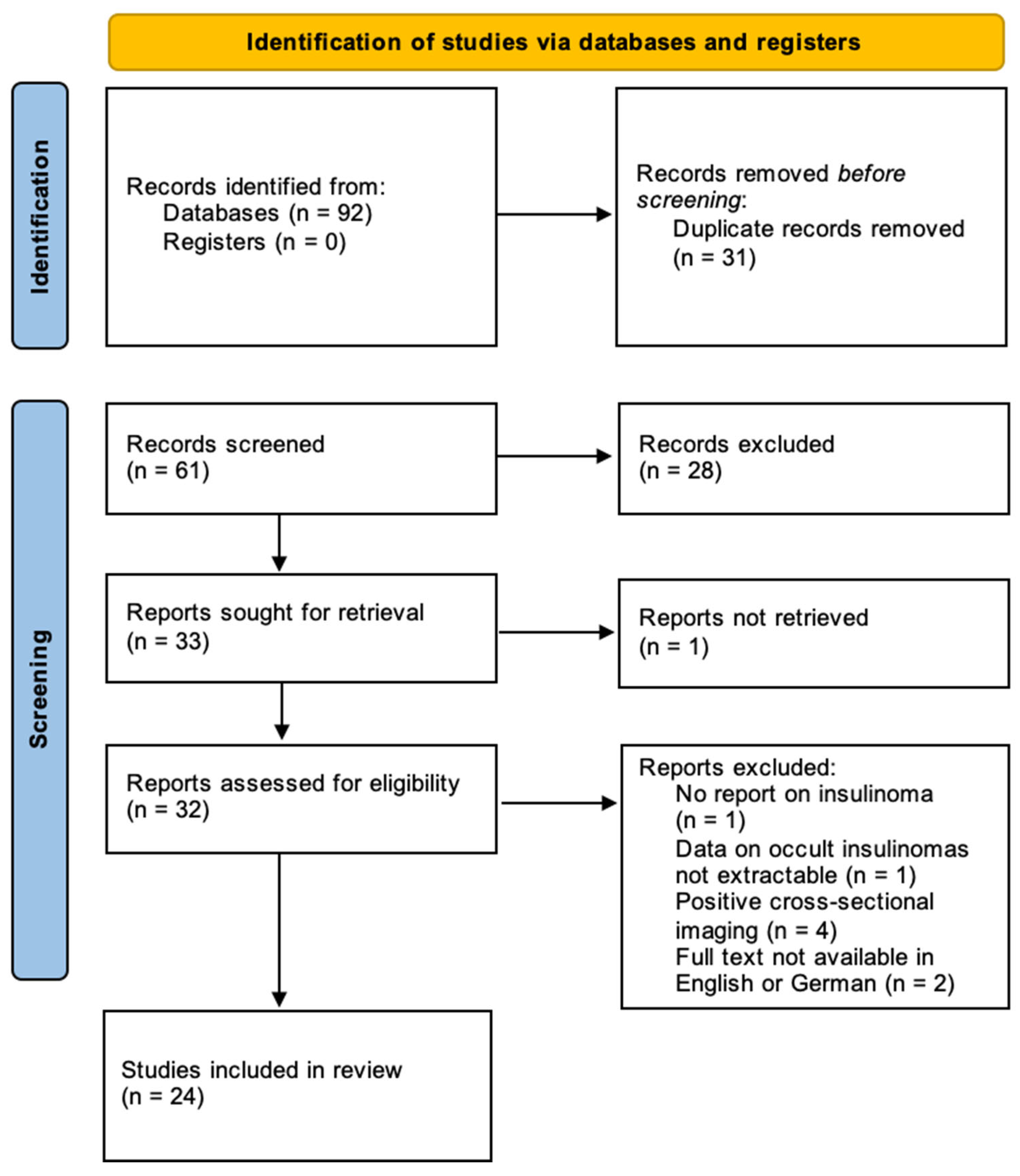

2.3. Literature Search

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hamburg Cohort of Occult Insulinomas

3.2. Systematic Review on Occult Insulinomas

4. Discussion

- Insulinomas can be negative in conventional MRI and CT. This is most frequent in female patients and in insulinomas of the pancreatic body and tail.

- If an insulinoma is clinically suspected (i.e., recurring hypoglycaemia and pathological fasting test) despite negative imaging, GLP-1R PET/CT should be conducted as an additional diagnostic tool if available.

- In case an insulinoma remains clinically suspected despite negative conventional imaging, EUS, and GLP-1R PET/CT, minimally invasive exploration with intraoperative ultrasound is feasible and safe.

- Parenchyma-sparing resections can be achieved even in cases of negative preoperative imaging.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLP-1R PET/CT | Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor positron emission tomography |

| CDC | Clavien–Dindo classification |

| cm | centimetre |

| CoE | Center of Excellence |

| CT | computed tomography |

| DGE | delayed gastric emptying |

| DP | distal pancreatectomy |

| ENETS | European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society |

| ERAS | Enhanced Recovery after Surgery |

| EUS | endoscopic ultrasound |

| FNA | fine needle aspiration |

| IOUS | intraoperative ultrasound |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| ISGPS | International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery |

| MDT | multidisciplinary team |

| MEN | Multiple endocrine neoplasia |

| MeSH | medical subject heading |

| mm | millimetre |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| N/A | not applicable |

| NET | neuroendocrine tumour |

| PHR | pancreatic head resection |

| pNET | pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour |

| POPF | postoperative pancreatic fistula |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis |

| SACST | selective pancreatic angiography and calcium stimulation catheterisation |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SRI | somatostatin receptor imaging |

References

- de Herder, W.W.; Hofland, J. Insulinoma. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000-2024, MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sada, A.; Yamashita, T.S.; Glasgow, A.E.; Habermann, E.B.; Thompson, G.B.; Lyden, M.L.; Dy, B.M.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Vella, A.; McKenzie, T.J. Comparison of benign and malignant insulinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, A.; Fischer, L.; Hafezi, M.; Dirlewanger, A.; Grenacher, L.; Diener, M.K.; Fonouni, H.; Golriz, M.; Garoussi, C.; Fard, N.; et al. A Systematic Review of Localization, Surgical Treatment Options, and Outcome of Insulinoma. Pancreas 2014, 43, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, S.; Pariani, D.; Calandra, C.; Marando, A.; Sessa, F.; Cortese, F.; Capella, C. Ectopic Duodenal Insulinoma: A Very Rare and Challenging Tumor Type. Description of a Case and Review of the Literature. Endocr. Pathol. 2013, 24, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, E.; Antwi, K.; Fani, M.; Wild, D. Innovative imaging of insulinoma: The end of sampling? A review. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2020, 27, R79–R92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, B.; Boujaoude, J. Occult sporadic insulinoma: Localization and surgical strategy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ba, Y.; Xing, Q.; Du, J.-L. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasound for insulinoma localization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kann, P.H.; Moll, R.; Bartsch, D.; Pfützner, A.; Forst, T.; Tamagno, G.; Goebel, J.N.; Fourkiotis, V.; Bergmann, S.R.; Collienne, M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) in insulinomas: Indications and clinical relevance in a single investigator cohort of 47 patients. Endocrine 2016, 56, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, J.; Guillaume, A.; Courtheoux, P.; Palazzo, L.; Rod, A.; Joubert, M.; Reznik, Y. Preoperative localization of an insulinoma: Selective arterial calcium stimulation test performance. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2015, 39, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.M.; Vella, A.; Service, F.J.; Grant, C.S.; Thompson, G.B.; Andrews, J.C. Impact of variant pancreatic arterial anatomy and overlap in regional perfusion on the interpretation of selective arterial calcium stimulation with hepatic venous sampling for preoperative localization of occult insulinoma. Surgery 2015, 158, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reubi, J.C.; Waser, B. Concomitant expression of several peptide receptors in neuroendocrine tumours: Molecular basis for in vivo multireceptor tumour targeting. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Imaging 2003, 30, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, K.; Fani, M.; Heye, T.; Nicolas, G.; Rottenburger, C.; Kaul, F.; Merkle, E.; Zech, C.J.; Boll, D.; Vogt, D.R.; et al. Comparison of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) PET/CT, SPECT/CT and 3T MRI for the localisation of occult insulinomas: Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy in a prospective crossover imaging study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Imaging 2018, 45, 2318–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofland, J.; Falconi, M.; Christ, E.; Castaño, J.P.; Faggiano, A.; Lamarca, A.; Perren, A.; Petrucci, S.; Prasad, V.; Ruszniewski, P.; et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society 2023 guidance paper for functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour syndromes. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 35, e13318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostambeigi, N.; Thompson, G.B. What should be done in an operating room when an insulinoma cannot be found? Clin. Endocrinol. 2009, 70, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, D.; Humburg, F.G.; Kann, P.H.; Rinke, A.; Luster, M.; Mahnken, A.; Bartsch, D.K. Changes in diagnosis and operative treatment of insulinoma over two decades. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiori, G.; Wiese, D.; Partelli, S.; Wächter, S.; Maurer, E.; Crippa, S.; Falconi, M.; Bartsch, D.K. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Treatment for Benign Sporadic Insulinoma Comparison of Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 3223–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, C.; Marchegiani, G.; Dervenis, C.; Sarr, M.; Hilal, M.A.; Adham, M.; Allen, P.; Andersson, R.; Asbun, H.J.; Besselink, M.G.; et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017, 161, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wente, M.N.; Bassi, C.; Dervenis, C.; Fingerhut, A.; Gouma, D.J.; Izbicki, J.R.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Padbury, R.T.; Sarr, M.G.; Traverso, L.W.; et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: A suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007, 142, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wente, M.N.; Veit, J.A.; Bassi, C.; Dervenis, C.; Fingerhut, A.; Gouma, D.J.; Izbicki, J.R.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Padbury, R.T.; Sarr, M.G.; et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH)–An International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 2007, 142, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Garden, O.J.; Padbury, R.; Rahbari, N.N.; Adam, R.; Capussotti, L.; Fan, S.T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Crawford, M.; Makuuchi, M.; et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: A definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery 2011, 149, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, G.; Mete, O.; Uccella, S.; Basturk, O.; La Rosa, S.; Brosens, L.A.A.; Ezzat, S.; de Herder, W.W.; Klimstra, D.S.; Papotti, M.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 115–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J.D.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloul, E.; Lassen, K.; Roulin, D.; Grass, F.; Perinel, J.; Adham, M.; Wellge, E.B.; Kunzler, F.; Besselink, M.G.; Asbun, H.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Pancreatoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Recommendations 2019. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 2056–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi, K.; Fani, M.; Nicolas, G.; Rottenburger, C.; Heye, T.; Reubi, J.C.; Gloor, B.; Christ, E.; Wild, D. Localization of Hidden Insulinomas with 68Ga-DOTA-Exendin-4 PET/CT: A Pilot Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjunan, D.; Grossman, A.B.; Singh, H.; Rai, R.; Bal, A.; Dutta, P. A Long Way to Find a Small Tumor: The Hunt for an Insulinoma. Jcem Case Rep. 2024, 2, luae192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongetti, E.; Lee, M.H.; A Pattison, D.; Hicks, R.J.; Norris, R.; Sachithanandan, N.; MacIsaac, R.J. Diagnostic challenges in a patient with an occult insulinoma:68 Ga-DOTA-exendin-4 PET/CT and 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT. Clin. Case Rep. 2018, 6, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, T.G.K.; Breuer, H.L.; Menge, B.A.; Giese, A.; Uhl, W.; Schmidt, W.E.; Tannapfel, A.; Wild, D.; Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Okkultes Insulinom als Ursache rezidivierender Hypoglykämien [Recurrent hypoglycemia due to an occult insulinoma]. Internist 2016, 57, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, D.; Banks, M.; Khoo, B.; Antwi, K.; Christ, E.; Campbell, F.; Raraty, M.; Wild, D. Application of Ga68-DOTA-exendin-4 PET/CT to localize an occult insulinoma. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 84, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erichsen, T.D.; Detlefsen, S.; Andersen, K.Ø.; Pedersen, H.; Rasmussen, L.; Gotthardt, M.; Pörksen, S.; Christesen, H.T. Occult insulinoma, glucagonoma and pancreatic endocrine pseudotumour in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, V.R.; Quinto-Reyes, F.; Paz-Ibarra, J.L. Severe hypoglycemia in a 14-year-old adolescent with negative imaging tests and inconclusive intra-arterial calcium stimulation test. Rev. Cuerpo Med. Hosp. Nac. 2024, 17, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Pérez, F.; Vilarrasa, N.; Huánuco, L.V.; Busquets, J.; Secanella, L.; Vercher-Conejero, J.L.; Vidal, N.; Cortés, S.N.; Villabona, C. Ectopic insulinoma: A systematic review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y. The Occult Insulinoma Was Localized Using Endoscopic Ultrasound Guidance: A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2025, 13, e9634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofland, J.; Refardt, J.C.; A Feelders, R.; Christ, E.; de Herder, W.W. Approach to the Patient: Insulinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larose, L.D.; Vroman, P.J.; Musick, S.R.; A Beauvais, A. A Case Report: Insulinoma in a Military Pilot Detected by 68Ga-Dotatate PET/CT. Mil. Med. 2020, 185, e1887–e1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, R.A.; Oza, U.D.; Hayden, R.; Fanous, H. Use of 68Ga DOTATATE, a new molecular imaging agent, for neuroendocrine tumors. Bayl. Univ. Med Cent. Proc. 2019, 33, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, N.; Kiesewetter, D.O.; Chen, X.; Li, F. 68Ga-NOTA-Exendin-4 PET/CT in Localization of an Occult Insulinoma and Appearance of Coexisting Esophageal Carcinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, A.; Yang, H.; Li, F. 68Ga-Exendin-4 PET/CT in Evaluation of Endoscopic Ultrasound–Guided Ethanol Ablation of an Insulinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yu, M.; Pan, Q.; Wu, W.; Zhang, T.; Kiesewetter, D.O.; Zhu, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. 68Ga-NOTA-exendin-4 PET/CT in detection of occult insulinoma and evaluation of physiological uptake. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Imaging 2014, 42, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Neyaz, Z.; Yadav, S.; Gupta, A.; Bhatia, E.; Mishra, S.K. Outcome of Pre-operative vs Intraoperative Localization Techniques in Insulinoma: Experience in a Tertiary Referral Center. Indian J. Surg. 2022, 86, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.Z.M.; Mohamad, A.F.; Zainordin, N.A.; Warman, N.A.E.; Hatta, S.F.W.M.; Ghani, R.A. A case report on a protracted course of a hidden insulinoma. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 64, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, A.K.; Pattison, D.A.; Hicks, R.J.; Hamblin, P.S.; Yates, C.J. Localisation of occult extra-pancreatic insulinoma using glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor molecular imaging. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olatunbosun, S.T.; Neely, J.L.; Ha, L.T.; Babu, V.K. Unmasking Long QT Syndrome in a Serviceman: Effects of Hypoglycemia and a Flight Duty Medical Examination. Mil. Med. 2025, 190, e2613–e2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkov, D.; Novosel, L.; Baretic, M.; Kastelan, D.; Smiljanic, R.; Padovan, R.S. Localization of Pancreatic Insulinomas with Arterial Stimulation by Calcium and Hepatic Venous Sampling-Presentation of a Single Centre Experience. Acta Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranaweerage, R.; Perera, S.; Sathischandra, H. Occult insulinoma with treatment refractory, severe hypoglycaemia in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome; difficulties faced during diagnosis, localization and management; a case report. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Jabeen, S.; Kiran, Z.; Minhas, M.; Uddin, M.; Islam, N. Localizing an occult Insulinoma by Selective Calcium Arterial Stimulation Test: First ever experience and a new dimension to diagnosis in Pakistan. J. Pak. Med Assoc. 2020, 70, 1636–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, K.; Murakami, T.; Fujimoto, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Miyake, K.K.; Otani, D.; Otsuki, S.; Shimizu, H.; Nagai, K.; Nomura, T.; et al. Case Report: A case of occult insulinoma localized by [18F] FB (ePEG12)12-exendin-4 positron emission tomography with negative findings of selective arterial calcium stimulation test. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1556813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, K.; Tomazic, A.; Skvarca, A.; Peitl, P.K.; Mikolajczak, R.; Hubalewska-Dydejczyk, A.; Lezaic, L. Superior Diagnostic Performance of the GLP-1 Receptor Agonist [Lys40(AhxHYNIC-[99mTc]/EDDA)NH2]-Exendin-4 over Conventional Imaging Modalities for Localization of Insulinoma. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2019, 22, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa-Staszczak, A.; Trofimiuk-Müldner, M.; Stefańska, A.; Tomaszuk, M.; Buziak-Bereza, M.; Gilis-Januszewska, A.; Jabrocka-Hybel, A.; Głowa, B.; Małecki, M.; Bednarczuk, T.; et al. 99mTc Labeled Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Analogue (99mTc-GLP1) Scintigraphy in the Management of Patients with Occult Insulinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasinghe, D.; Gunatilake, S.S.C.; Dassanyake, V.E.; Garusinghe, C.; Ganewaththa, E.; Appuhamy, C.; Somasundaram, N.P.; Sivaganesh, S. Seeking the unseen: Localization and surgery for an occult sporadic insulinoma. Ann. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2020, 24, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.M.; Vella, A.; Service, F.J.; Thompson, G.; Andrews, J.C. Selective Arterial Calcium Stimulation with Hepatic Venous Sampling in Patients with Recurrent Endogenous Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia and Metastatic Insulinoma: Evaluation in Five Patients. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 28, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.; Omar, J.; Yusof, N.A.A.C.S. Insulinoma of Pancreatic Head Localized by Intra-Arterial Calcium Stimulation with Hepatic Venous Sampling. Bangladesh J. Med Sci. 2021, 20, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pan, Q.; Liu, S.; Feng, J.; Yu, M.; Li, N.; Xu, Q.; Han, X.; Li, F.; Luo, Y. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor PET/CT with 68Ga-exendin-4 for localizing insulinoma: A real-world, single-center study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Imaging 2025, 52, 4487–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Ding, M. Neuropsychiatric Profiles of Patients with Insulinomas. Eur. Neurol. 2009, 63, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Q.; Pei, Y.; Du, J.; Dou, J.; Ba, J.; Lv, Z.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Management of Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Single Institution 20-Year Experience with 286 Patients. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhman, M.P.; Karam, J.H.; Shaver, J.; Siperstein, A.E.; Duh, Q.Y.; Clark, O.H. Insulinoma--experience from 1950 to 1995. West J Med. 1998, 169, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, E.; Wild, D.; Ederer, S.; Béhé, M.; Nicolas, G.; E Caplin, M.; Brändle, M.; Clerici, T.; Fischli, S.; Stettler, C.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor imaging for the localisation of insulinomas: A prospective multicentre imaging study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013, 1, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Christ, E.; Caplin, M.E.; Kurzawinski, T.R.; Forrer, F.; Brändle, M.; Seufert, J.; Weber, W.A.; Bomanji, J.; Perren, A.; et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Versus Somatostatin Receptor Targeting Reveals 2 Distinct Forms of Malignant Insulinomas. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Antwi, K.; Fani, M.; Christ, E.R. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor as Emerging Target: Will It Make It to the Clinic? J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 62, 44S–50S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterle, M.P.; Husari, A.; Prozmann, S.N.; Wiethoff, H.; Stenzinger, A.; Röhrich, M.; Pfeiffer, U.; Kießling, W.R.; Engel, H.; Sourij, H.; et al. Diffuse, Adult-Onset Nesidioblastosis/Non-Insulinoma Pancreatogenous Hypoglycemia Syndrome (NIPHS): Review of the Literature of a Rare Cause of Hyperinsulinemic Hypoglycemia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, E.; Wild, D.; Antwi, K.; Waser, B.; Fani, M.; Schwanda, S.; Heye, T.; Schmid, C.; Baer, H.U.; Perren, A.; et al. Preoperative localization of adult nesidioblastosis using 68Ga-DOTA-exendin-4-PET/CT. Endocrine 2015, 50, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiella, S.; De Pastena, M.; Landoni, L.; Esposito, A.; Casetti, L.; Miotto, M.; Ramera, M.; Salvia, R.; Secchettin, E.; Bonamini, D.; et al. Is there a role for near-infrared technology in laparoscopic resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors? Results of the COLPAN “colour-and-resect the pancreas” study. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 4478–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nießen, A.; Bechtiger, F.A.; Hinz, U.; Lewosinska, M.; Billmann, F.; Hackert, T.; Büchler, M.W.; Schimmack, S. Enucleation Is a Feasible Procedure for Well-Differentiated pNEN—A Matched Pair Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carbonnières, A.; Challine, A.; Cottereau, A.S.; Coriat, R.; Soyer, P.; Ali, E.A.; Prat, F.; Terris, B.; Bertherat, J.; Dousset, B.; et al. Surgical management of insulinoma over three decades. HPB 2021, 23, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, T.; van Hilst, J.; van Santvoort, H.; Boerma, D.; van den Boezem, P.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.; Dejong, C.; van Duyn, E.; Dijkgraaf, M.; et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): A Multicenter Patient-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholten, L.; Klompmaker, S.; Van Hilst, J.; Annecchiarico, M.M.; Balzano, G.; Casadei, R.; Fabre, J.-M.; Falconi, M.; Ferrari, G.; Kerem, M.; et al. Outcomes After Minimally Invasive Versus Open Total Pancreatectomy: A Pan-European Propensity Score Matched Study. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zureikat, A.H.; Moser, A.J.; Boone, B.A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Zenati, M.; Zeh, H.J.I. 250 Robotic Pancreatic Resections: Safety and feasibility. Ann Surg. 2013, 258, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Geng, D.; Feng, Y.; Sun, M. Safety and efficacy for robot-assisted versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 27, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, R.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Kulu, Y.; Sander, A.; Klose, C.; Behnisch, R.; Joos, M.C.; Kalkum, E.; Nickel, F.; Knebel, P.; et al. Robotic versus open partial pancreatoduodenectomy (EUROPA): A randomised controlled stage 2b trial. Lancet Reg. Heal.-Eur. 2024, 39, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Han, B.; Chen, X.; Tan, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, G.; Gao, Y.; et al. Perioperative and Oncological Outcomes of Robotic Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Low-Risk Surgical Candidates: A Multicenter Propensity Score-Matched Study. Ann. Surg. 2021, 277, e864–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korrel, M.; Jones, L.R.; van Hilst, J.; Balzano, G.; Björnsson, B.; Boggi, U.; Bratlie, S.O.; Busch, O.R.; Butturini, G.; Capretti, G.; et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy for resectable pancreatic cancer (DIPLOMA): An international randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Reg. Heal.-Eur. 2023, 31, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crinò, S.F.; Napoleon, B.; Facciorusso, A.; Lakhtakia, S.; Borbath, I.; Caillol, F.; Pham, K.D.-C.; Rizzatti, G.; Forti, E.; Palazzo, L.; et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Radiofrequency Ablation Versus Surgical Resection for Treatment of Pancreatic Insulinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2834–2843.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hamburg Cohort (n = 8) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n/All | IQR/%/SD | |

| Median age [years] | 50.5 | 47.25–65.25 (IQR) |

| Gender | 4:4 | 50.0%:50.0% |

| Preoperative diagnostics | ||

| Preoperative CT (positive/conducted) | 3/5 | 60.0% |

| Preoperative MRI (positive/conducted) | 5/8 | 62.5% |

| Preoperative EUS (positive/conducted) | 3/5 | 60.0% |

| Preoperative SRI (positive/conducted) | 1/4 | 25.0% |

| Preoperative GLP-1R PET/CT (positive/conducted) | 1/2 | 50.0% |

| Operative details | ||

| Insulinoma localisation | Head: 2/8 | 25.0% |

| Body/Tail: 6/8 | 75.0% | |

| Approach | Laparoscopic: 3/8 | 37.5% |

| Robotic: 5/8 | 62.5% | |

| Conversion rate | Laparoscopic: 1/3 | 33.3% |

| Robotic: 1/5 | 20.0% | |

| Operation | Enucleation: 2/8 | 25.0% |

| PHR: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| DP:5/8 | 62.5% | |

| Postoperative drain use | Yes: 7/8 | 87.5% |

| No: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| Postoperative major complication (CDC ≥ 3a) | 1/8 | 12.5% |

| Median length of stay [days] | 8.5 | 6.5–18.25 (IQR) |

| Histopathological characteristics | ||

| Mean tumour size [mm] | 17.2 | 13.3 (SD) |

| Tumour grading | G1: 2/8 | 25.0% |

| G2: 6/8 | 75.0% | |

| pT stage 1 | pT1: 7/8 | 87.5% |

| pT2: 0/8 | 0% | |

| pT3: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| pT4: 0/8 | 0% | |

| pN stage 1 | pN0: 7/8 | 87.5% |

| pN1: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| c/pM stage 1 | c/pM0: 7/8 | 87.5% |

| c/pM1: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| R stage 1 | R0: 5/8 | 62.5% |

| R1: 2/8 | 25.0% | |

| Rx: 1/8 | 12.5% | |

| Study | Number of Patients n | Male/Female (%) n:n (%:%) | Median Age (IQR) [Years] | MEN1-Patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamburg cohort | 2 | 1:1 (50.0:50.0) | 59.5 (51–68) | 0 |

| Antwi, 2015 [26] | 4 | 2:2 (50.0:50.0) | 55.5 (41.3–63.8) | 0 |

| Antwi, 2018 [12] | 34 | n/A | N/A (N/A) | 0 |

| Arjunan, 2024 [27] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 35 (N/A) | 0 |

| Bongetti, 2018 [28] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 82 (N/A) | 0 |

| Breuer, 2016 [29] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 64 (N/A) | 0 |

| Cuthbertson, 2016 [30] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 49 (N/A) | 0 |

| Erichsen, 2020 [31] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 14 (N/A) | 1 (100) |

| Guo, 2025 [34] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 44 (N/A) | 0 |

| Hofland, 2024 [35] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 45 (N/A) | 0 |

| Larose, 2020 [36] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 37 (N/A) | 0 |

| Luo, 2015 [40] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 52 (N/A) | 0 |

| Luo, 2016 [38] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 61 (N/A) | 0 |

| Mishra, 2022 [41] | 4 | N/A | N/A (N/A) | N/A |

| Mohamed Shah, 2021 [42] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 33 (N/A) | 0 |

| Morera, 2016 [9] | 11 | N/A | N/A (N/A) | N/A |

| Perkov, 2016 [45] | 2 | 0:2 (0:100) | 33.5 (30–37) | 1 (50.0) |

| Ranaweerage, 2022 [46] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 23 (N/A) | 1 (100) |

| Rashid, 2020 [47] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 40 (N/A) | 0 |

| Sakaki, 2025 [48] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 67 (N/A) | 0 |

| Senica, 2020 [49] | 5 | 0:5 (0:100) | 57.0 (41.5–68.5) | 0 |

| Sowa-Staszczak, 2016 [50] | 22 | 10:12 (45.5:54.5) | 48 (34–60.5) | N/A |

| Subasinghe, 2020 [51] | 1 | 1:0 (100:0) | 39 (N/A) | 0 |

| Thompson, 2015 [10] | 42 | 15:27 (45.7:64.3) | 48.6 (18.7–76.7) | 4 (9.5) |

| Wong, 2021 [53] | 1 | 0:1 (0:100) | 33 (N/A) | 0 |

| Total | 142 | 34:59 (36.6:63.4) | 48.0 (35.0–82.0) 1 | 7 (6.7) |

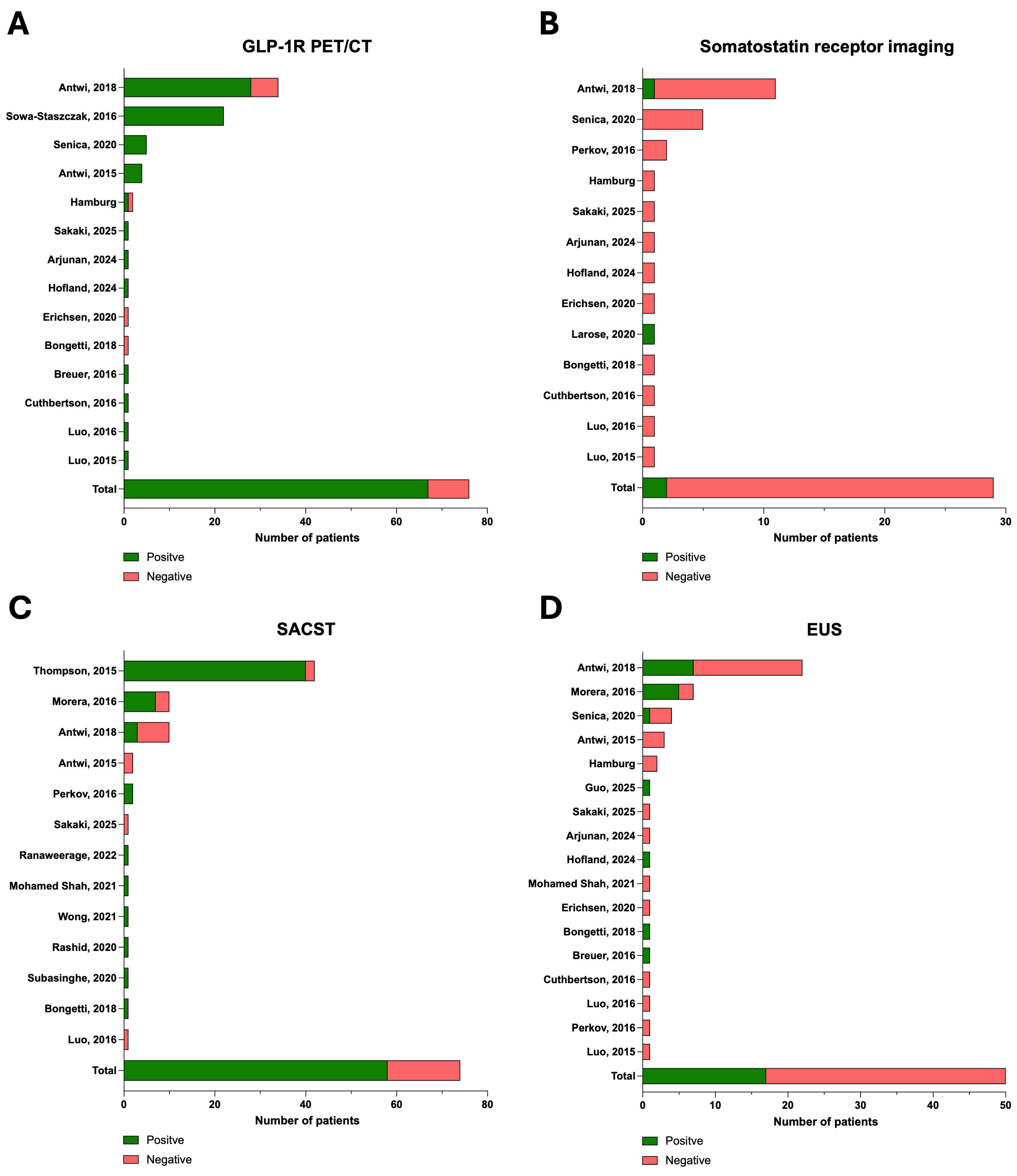

| Study | MRI Conducted n (%) | CT Conducted n (%) | SRI Conducted n (%) | SRI Positive n (%) | GLP-1R PET/CT Conducted n (%) | GLP-1R PET/CT Positive n (%) | EUS Conducted n (%) | EUS Positive n (%) | SACST Conducted n (%) | SACST Positive n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamburg cohort | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) | 0 1 | 0 | - |

| Antwi, 2015 [26] | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | - | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (75) | 0 | 2 (50.0) | 0 |

| Antwi, 2018 [12] | 25 (73.5) | 16 (47.1) | 10 (29.4) | 1 (2.9) | 34 (100) | 28 (82.4) | 22 (64.7) | 7 (31.8) | 10 (29.4) | 3 (30) |

| Arjunan, 2024 [27] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Bongetti, 2018 [28] | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 2 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Breuer, 2016 [29] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - |

| Cuthbertson, 2016 [30] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Erichsen, 2020 [31] | 0 2 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 3 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Guo, 2025 [34] | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - |

| Hofland, 2024 [35] | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - |

| Larose, 2020 [36] | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Luo, 2015 [40] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Luo, 2016 [38] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Mishra, 2022 [41] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mohamed Shah, 2021 [42] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Morera, 2016 [9] | 10 (90.9) | 9 (81.8) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 7 (63.6) | 5 (71.4) | 10 (90.9) | 7 (70.0) |

| Perkov, 2016 [45] | N/A | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | - | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Ranaweerage, 2022 [46] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Rashid, 2020 [47] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Sakaki, 2025 [48] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) 3 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 2 | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Senica, 2020 [49] | 3 (60.0) | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 0 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | - |

| Sowa-Staszczak, 2016 [50] | 22 (100) | 22 (100) | 0 | - | 22 (100) | 22 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Subasinghe, 2020 [51] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Thompson, 2015 [10] | 42 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 42 (100) | 40 (95.2) |

| Wong, 2021 [53] | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Total | 118/136 (86.8) | 72/138 (52.2) | 27/96 (28.1) | 2/27 (7.4) | 76/96 (79.2) | 67/76 (88.2) | 50/96 (52.1) | 17/50 (34.0) | 74/138 (53.6) | 58/74 (78.4) |

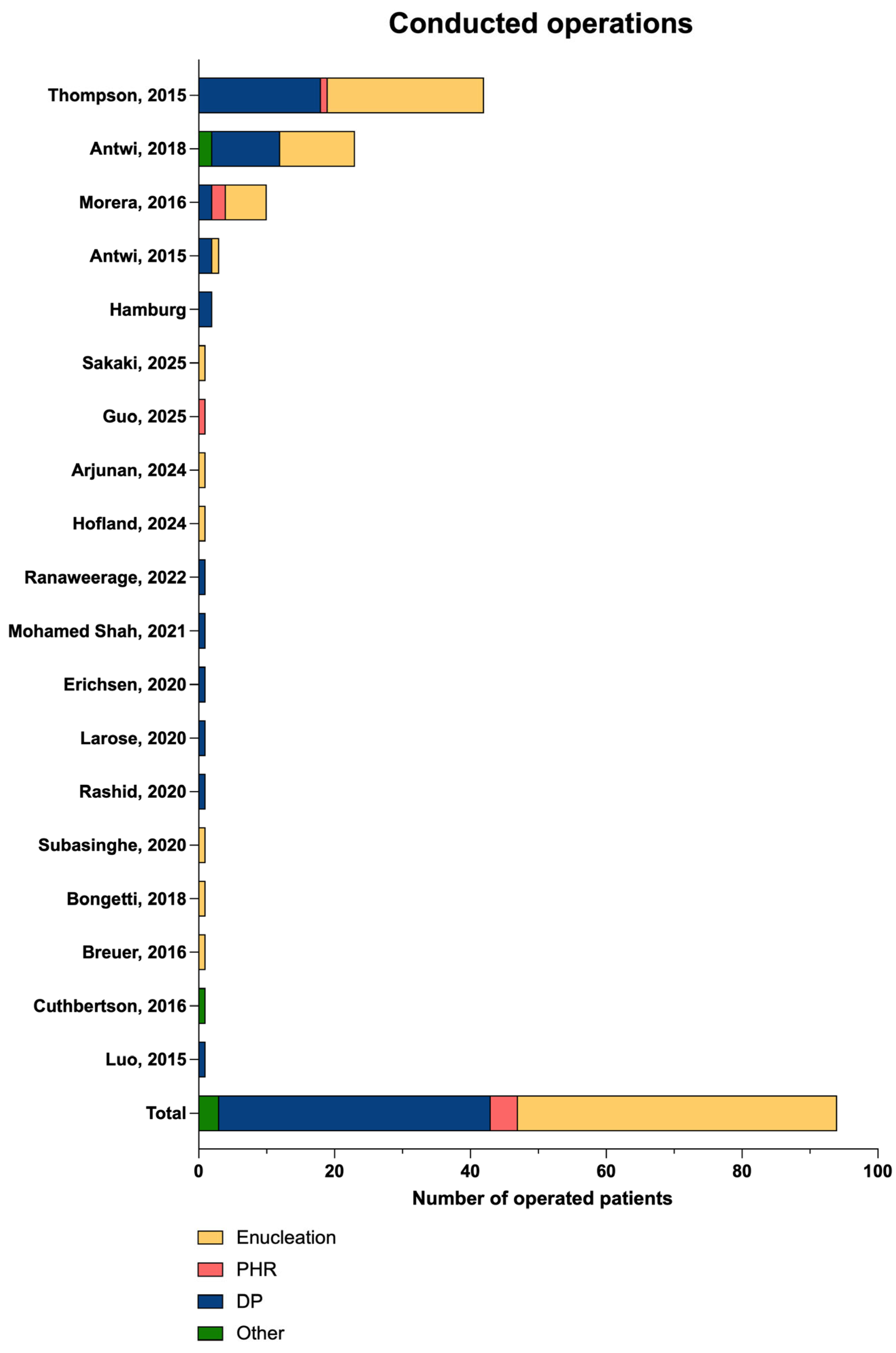

| Study | Number of Operations n/All | Minimally Invasive Approach (%) n (%) | Intraoperative Ultrasound Conducted n (%) | Type of Operation n (%) | Postoperative Major Complications 1 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamburg cohort | 2/2 | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 2 (100) Other: 0 | 0/2 (0) |

| Antwi, 2015 [26] | 3/4 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation: 1 (33.3) PHR: 0 DP: 2 (66.7) Other: 0 | N/A |

| Antwi, 2018 [12] | 23/34 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation:11 (47.8) PHR: 0 DP: 10 (43.5) Other: 2 (8.7) | N/A |

| Arjunan, 2024 [27] | 1/1 | 0 | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Bongetti, 2018 [28] | 1/1 | 1 (100) | N/A | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Breuer, 2016 [29] | 1/1 | 0 | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Cuthbertson, 2016 [30] | 1/1 | 0 | N/A | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 1 (100) | 0/1 (0) |

| Erichsen, 2020 [31] | 1/1 | 0 | N/A | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 1/1 (100) |

| Guo, 2025 [34] | 1/1 | 0 | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 1 (100) DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Hofland, 2024 [35] | 1/1 | 1 (100) | N/A | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Larose, 2020 [36] | 1/1 | 1 (100) | N/A | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Luo, 2015 [40] | 1/1 | N/A | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Luo, 2016 [38] | 1/1 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation: N/A PHR: N/A DP: N/A Other: N/A | 0/1 (0) |

| Mishra, 2022 [41] | 4/4 | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | Enucleation: N/A PHR: N/A DP: N/A Other: N/A | N/A |

| Mohamed Shah, 2021 [42] | 1/1 | N/A | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Morera, 2016 [9] | 10/11 | N/A | 6 (60.0) | Enucleation: 6 (60.0) PHR: 2 (20.0) DP: 2 (20.0) Other:0 | N/A |

| Perkov, 2016 [45] | 2/2 | 0 | 2 (100) | Enucleation: N/A PHR: N/A DP: N/A Other: N/A | N/A |

| Ranaweerage, 2022 [46] | 1/1 | 0 | N/A | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Rashid, 2020 [47] | 1/1 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation: 0 PHR: 0 DP: 1 (100) Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Sakaki, 2025 [48] | 1/1 | 1 (100) | N/A | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Senica, 2020 [49] | 5/5 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation: N/A PHR: N/A DP: N/A Other: N/A | 0/5 (0) |

| Sowa-Staszczak, 2016 [50] | 19/22 | N/A | N/A | Enucleation: N/A PHR: N/A DP: N/A Other: N/A | 1/19 (5.3) |

| Subasinghe, 2020 [51] | 1/1 | 0 | 1 (100) | Enucleation: 1 (100) PHR: 0 DP: 0 Other: 0 | 0/1 (0) |

| Thompson, 2015 [10] | 42/42 | N/A | 34 (81.0) | Enucleation: 23 (54.8) PHR:1 (2.3) DP: 18 (42.9) Other: 0 | 0/42 (0) |

| Wong, 2021 [53] | 0/1 | - | - | Enucleation: - PHR: - DP: - Other: - | - |

| Total | 125/142 (88.0) | 10/19 (52.6) | 53/66 (80.3) | Enucleation: 47 (50.0) PHR: 4 (4.3) DP: 40 (42.6) Other: 3 (3.2) | 2/83 (2.4) |

| Study | Mean Tumour Size [mm] | Grading | Localisation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (SD) | G1 | G2 | G3 | Head | Body/Tail | ||

| Hamburg cohort | 13.0 | (±4.2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Antwi, 2015 [26] | 9.3 | (±1.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 3 |

| Antwi, 2018 [12] | 11.8 | (±5.0) | 16 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 19 |

| Arjunan, 2024 [27] | 15.0 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 0 |

| Bongetti, 2018 [28] | 11.0 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Breuer, 2016 [29] | 7.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cuthbertson, 2016 [30] | 15.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Erichsen, 2020 [31] | 10.0 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Guo, 2025 [34] | 14.0 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Hofland, 2024 [35] | 12.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Larose, 2020 [36] | 19.0 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Luo, 2015 [40] | N/A | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Luo, 2016 [38] | 25.0 | (N/A) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mishra, 2022 [41] | N/A | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mohamed Shah, 2021 [42] | 10.1 | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0 | 1 |

| Morera, 2016 [9] | 13.7 | (±4.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 | 4 |

| Perkov, 2016 [45] | 18.0 | (±1.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 0 |

| Ranaweerage, 2022 [46] | N/A | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rashid, 2020 [47] | 15.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sakaki, 2025 [48] | 23.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Senica, 2020 [49] | 15.4 | (±8.4) | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Sowa-Staszczak, 2016 [50] | N/A | (N/A) | 18 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Subasinghe, 2020 [51] | 10.0 | (N/A) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Thompson, 2015 [10] | 16.0 | (±0.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wong, 2021 [53] | N/A | (N/A) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 14.2 | ±4.5 | 44/56 (78.6%) | 10/56 (17.9%) | 2/56 (3.6%) | 17/62 (27.4%) | 45/62 (72.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ritter, A.S.; Ockenga, F.; Steinkraus, K.C.; Poppinga, J.; von Kroge, P.H.; Amin, T.; Viol, F.; Fründt, T.W.; Nickel, F.; Hackert, T.; et al. Minimally Invasive Resection of Occult Insulinomas—Experience from an ENETS Centre of Excellence and Review of the Literature. Cancers 2025, 17, 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233857

Ritter AS, Ockenga F, Steinkraus KC, Poppinga J, von Kroge PH, Amin T, Viol F, Fründt TW, Nickel F, Hackert T, et al. Minimally Invasive Resection of Occult Insulinomas—Experience from an ENETS Centre of Excellence and Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233857

Chicago/Turabian StyleRitter, Alina S., Feline Ockenga, Kira C. Steinkraus, Jelte Poppinga, Philipp H. von Kroge, Tania Amin, Fabrice Viol, Thorben W. Fründt, Felix Nickel, Thilo Hackert, and et al. 2025. "Minimally Invasive Resection of Occult Insulinomas—Experience from an ENETS Centre of Excellence and Review of the Literature" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233857

APA StyleRitter, A. S., Ockenga, F., Steinkraus, K. C., Poppinga, J., von Kroge, P. H., Amin, T., Viol, F., Fründt, T. W., Nickel, F., Hackert, T., & Nießen, A. (2025). Minimally Invasive Resection of Occult Insulinomas—Experience from an ENETS Centre of Excellence and Review of the Literature. Cancers, 17(23), 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233857