Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Diagnostic Performance of Functional Imaging (18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA-, 68Ga-DOTA- and 18F-Fluoro-Deoxyglucose-Based PET/CT) and of 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in 57 Patients and 527 Controls During Long-Term Follow-Up

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

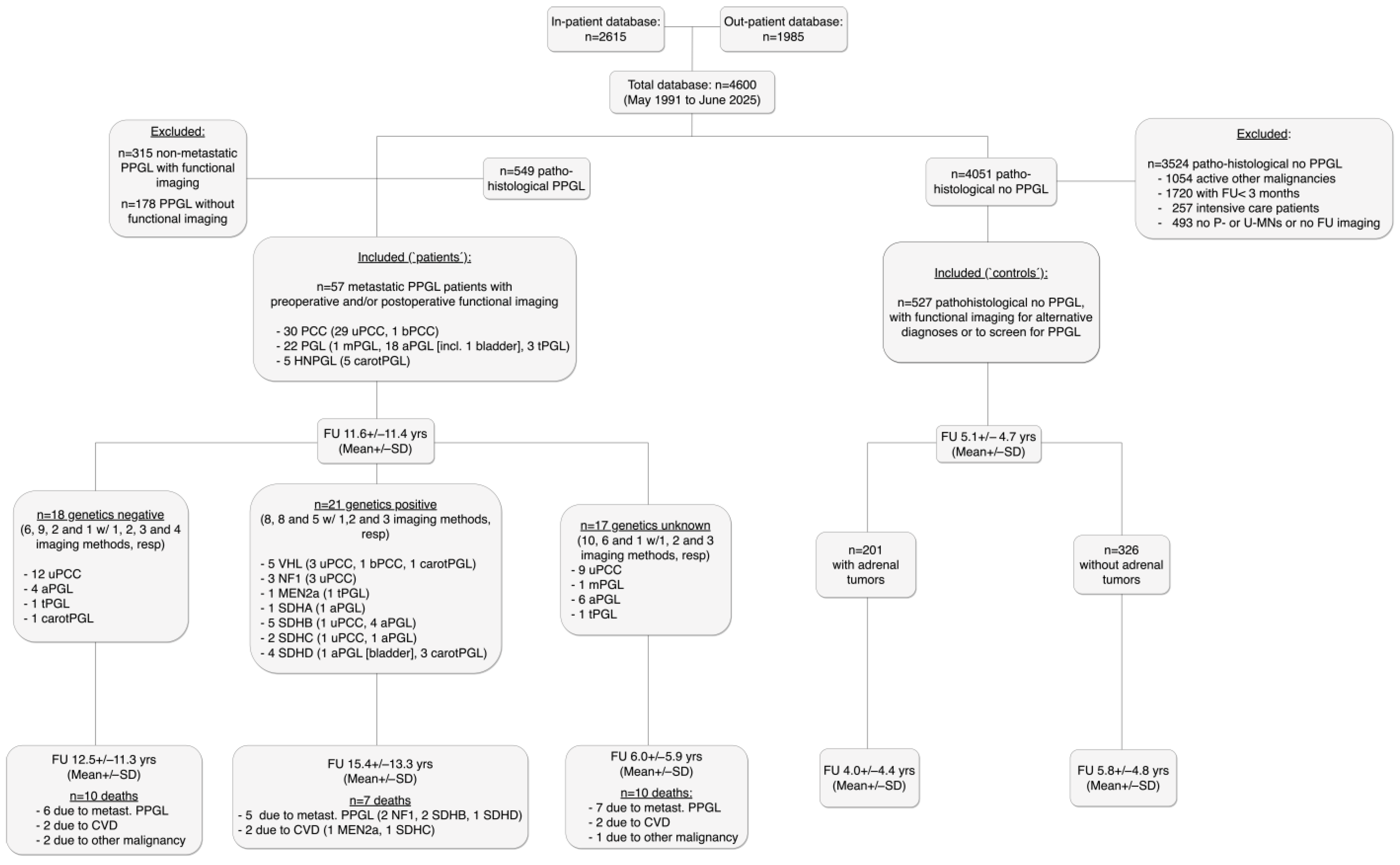

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Imaging Protocols

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Therapies During FU (i.e., After First Surgery)

3.3. Diagnostic Performance of Imaging Modalities

3.3.1. Patient-Based Analysis

For All Metastases Together

For Detection of Metastases in Lnn, Parenchymatous Organs and Bone

3.3.2. Lesion-Based Analysis

For All Metastases Together

For Detection of Metastases in Lnn, Parenchymatous Organs and Bone

3.3.3. Imaging-Based Analysis

For All Metastases Together

For Detection of Metastases in Lnn, Parenchymatous Organs and Bone

3.3.4. False Negative and False Positive Results

False Negative Results

False Positive Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fassnacht, M.; Arlt, W.; Bancos, I.; Dralle, H.; Newell-Price, J.; Sahdev, A.; Tabarin, A.; Terzolo, M.; Tsagarakis, S.; Dekkers, O.M. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 175, G1–G34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascón, A.; Calsina, B.; Monteagudo, M.; Mellid, S.; Díaz-Talavera, A.; Currás-Freixes, M.; Robledo, M. Genetic bases of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2023, 70, e220167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raber, W.; Schendl, R.; Arikan, M.; Scheuba, A.; Mazal, P.; Stadlmann, V.; Lehner, R.; Zeitlhofer, P.; Baumgartner-Parzer, S.; Gabler, C.; et al. Metastatic disease and major adverse cardiovascular events preceding diagnosis are the main determinants of disease-specific survival of pheochromocytoma/ paraganglioma: Long-term follow-up of 303 patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1419028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, R.; Burnichon, N.; Cascon, A.; Benn, D.E.; Bayley, J.-P.; Welander, J.; Tops, C.M.; Firth, H.; Dwight, T.; Ercolino, T.; et al. Consensus Statement on next-generation-sequencing-based diagnostic testing of hereditary phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nölting, S.; Bechmann, N.; Taieb, D.; Beuschlein, F.; Fassnacht, M.; Kroiss, M.; Eisenhofer, G.; Grossman, A.; Pacak, K. Personalized Management of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 199–239, Erratum in Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 440. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab044. Erratum in Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 437–439. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mete, O.; Asa, S.L.; Gill, A.J.; Kimura, N.; de Krijger, R.R.; Tischler, A. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 90–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crona, J.; Taïeb, D.; Pacak, K. New Perspectives on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Toward a Molecular Classification. Endocr. Rev. 2017, 38, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raber, W.; Scheuba, A.; Marculescu, R.; Esterbauer, H.; Rohrbeck, J. Locally advanced pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma exhibit high metastatic recurrence and disease specific mortality rates: Long-term follow-up of 283 patients. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 192, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.F. Metastatic Pheochromocytoma: In Search of a Cure. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqz019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmers, H.J.; Chen, C.C.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Whatley, M.; Ling, A.; Havekes, B.; Eisenhofer, G.; Martiniova, L.; Adams, K.T.; Pacak, K. Comparison of 18F-fluoro-L-DOPA, 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose, and 18F-fluorodopamine PET and 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in the localization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4757–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, D.; Hicks, R.J.; Hindié, E.; Guillet, B.A.; Avram, A.; Ghedini, P.; Timmers, H.J.; Scott, A.T.; Elojeimy, S.; Rubello, D.; et al. European Association of Nuclear Medicine Practice Guideline/Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Procedure Standard 2019 for radionuclide imaging of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 2112–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Araujo-Castro, M.; Pascual-Corrales, E.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Molina-Cerrillo, J.; Lorca, A.M. Role of imaging test with radionuclides in the diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2022, 69, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbehoj, A.; Iversen, P.; Kramer, S.; Stochholm, K.; Poulsen, P.L.; Hjorthaug, K.; Søndergaard, E. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma-18F-FDOPA vs Somatostatin Analogues. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, K.; Yu, H.; Ren, Y.; Yang, J. Diagnostic Performance of [18 F] FDOPA PET/CT and Other Tracers in Pheochromocytoma: A Meta-Analysis. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z. 68Ga-somatostatin receptor analogs and 18F-FDG PET/CT in the localization of metastatic pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas with germline mutations: A meta-analysis. Acta Radiol. 2018, 59, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnaldi, S.; E Mayerhoefer, M.; Khameneh, A.; Schuetz, M.; Javor, D.; Mitterhauser, M.; Dudczak, R.; Hacker, M.; Karanikas, G. (18)F-DOPA PET/CT and MRI: Description of 12 histologically-verified pheochromocytomas. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Rabadi, K.; Weber, M.; Mayerhofer, M.; Nakuz, T.; Scherer, T.; Mitterhauser, M.; Dudczak, R.; Hacker, M.; Karanikas, G. Clinical Value of 18F-fluorodihydroxyphenylalanine Positron Emission Tomography/Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography (18F-DOPA PET/CT) in Patients with Suspected Paraganglioma. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 4187–4193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Rainer, E.; Hargitai, L.; Jiang, Z.; Karanikas, G.; Traub-Weidinger, T.; Crevenna, R.; Hacker, M.; Li, S. The role of [18F]F-DOPA PET/CT in diagnostic and prognostic assessment of medullary thyroid cancer: A 15-year experience with 109 patients. Eur. Thyroid J. 2024, 13, e240089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Prosch, H.; Herold, C.J.; Weber, M.; Karanikas, G. Assessment of pulmonary melanoma metastases with 18F-FDG PET/CT: Which PET-negative patients require additional tests for definitive staging? Eur. Radiol. 2012, 22, 2451–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzaczy, D.; Fueger, B.; Hoeller, C.; Haug, A.R.; Staudenherz, A.; Berzaczy, G.; Weber, M.; Mayerhoefer, M.E. Whole-Body [18F]FDG-PET/MRI vs. [18F]FDG-PET/CT in Malignant Melanoma. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2020, 22, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzaczy, D.; Giraudo, C.; Haug, A.R.; Raderer, M.; Senn, D.; Karanikas, G.; Weber, M.; Mayerhoefer, M.E. Whole-Body 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/MRI Versus 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Prospective Study in 28 Patients. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brown, L.D.; Cai, T.T.; DasGupta, A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat. Sci. 2001, 16, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Jha, A.; Ling, A.; Chen, C.C.; Millo, C.; Kuo, M.J.M.; Nazari, M.A.; Talvacchio, S.; Charles, K.; Miettinen, M.; et al. Performances of Functional and Anatomic Imaging Modalities in Succinate Dehydrogenase A-Related Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Suh, C.H.; Woo, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.J. Performance of 68Ga-DOTA-Conjugated Somatostatin Receptor-Targeting Peptide PET in Detection of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J. Nucl. Med. 2019, 60, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, I.; Wolf, K.I.B.; Chui, C.H.M.; Millo, C.M.; Pacak, K.M. Relevant Discordance Between 68Ga-DOTATATE and 68Ga-DOTANOC in SDHB-Related Metastatic Paraganglioma: Is Affinity to Somatostatin Receptor 2 the Key? Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reubi, J.; Waser, B.; Schaer, J.-C.; Laissue, J.A. Somatostatin receptor sst1-sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 28, 836–846, Erratum in Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 28, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.; Patel, M.; Ling, A.; Shah, R.; Chen, C.C.; Millo, C.; Nazari, M.A.; Sinaii, N.; Charles, K.; Kuo, M.J.M.; et al. Diagnostic performance of [68Ga]DOTATATE PET/CT, [18F]FDG PET/CT, MRI of the spine, and whole-body diagnostic CT and MRI in the detection of spinal bone metastases associated with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 6488–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janssen, I.; Chen, C.C.; Millo, C.M.; Ling, A.; Taieb, D.; Lin, F.I.; Adams, K.T.; Wolf, K.I.; Herscovitch, P.; Fojo, A.T.; et al. PET/CT comparing 68Ga-DOTATATE and other radiopharmaceuticals and in comparison with CT/MRI for the localization of sporadic metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 1784–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Sarathi, V.; Malhotra, G.; Verma, P.; Hira, P.; Badhe, P.; Memon, S.S.; Barnabas, R.; A Patil, V.; Anurag; et al. The Utility of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in Localizing Primary/Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Asian Indian Experience. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 25, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kroiss, A.; Uprimny, C.; Shulkin, B.; Gruber, L.; Frech, A.; Jazbec, T.; Girod, P.; Url, C.; Thomé, C.; Riechelmann, H.; et al. 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in the localization of metastatic extra-adrenal paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma compared with 18F-DOPA PET/CT. Rev. Española De Med. Nucl. E Imagen Mol. 2019, 38, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, P.; Kramer, S.; Ebbehoj, A.; Søndergaard, E.; Stochholm, K.; Poulsen, P.L.; Hjorthaug, K. [18F]FDOPA PET/CT is superior to [68Ga]DOTATOC PET/CT in diagnostic imaging of pheochromocytoma. EJNMMI Res. 2023, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bian, L.; Xu, J.; Li, P.; Bai, L.; Song, S. Comparison of 68Ga-DOTANOC and 18F-FDOPA PET/CT for Detection of Recurrent or Metastatic Paragangliomas. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2025, 7, e240059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Long, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Z.; Zha, Z.; Zhang, X. Head-to-head comparison between [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-NOC and [18F]DOPA PET/CT in a diverse cohort of patients with pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PCC, Genet Neg (N = 11) | PCC, Genet Pos (N = 9) | PCC, Genet Unknown (N = 10) | PGL, Genet Neg (N = 5) | PGL, Genet Pos (N = 9) | PGL, Genet Unknown (N = 8) | HNPGL, Genet Pos (N = 5) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st surgery, years (mean ± SD) | 48.8 ± 13.8 | 24.7 ± 12.4 | 36.7 ± 13.0 | 50.8 ± 11.6 | 35.0 ± 21.2 | 46.7 ± 17.0 | 28.5 ± 10.6 | 0.04 |

| Male sex (%) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (55.6) | 6 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 5 (55.6) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (60.0) | 0.10 * |

| Tumor size (cm), mean ± SD (range) | 7.1 ± 3.2 (3.5–13.5) | 11.0 ± 4.3 (5.8–17.0) | 10.3 ± 4.5 (5.5–18.0) | 8.3 ± 2.9 (4.5–12) | 5.5 ± 3.1 (2.0–10.0) | 7.6 ± 6.6 (1.5–18) | 4.4 ± 1.1 (3.5–6.0) | 0.21 |

| Metastatic disease at 1st surgery, N (%) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (80.0) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (50.0) | 0 | 0.72 * |

| Location of primary metastatic disease (N) | Loc Lnn (1), Loc Lnn + lungs (1), dissem. (1) | Loc Lnn (2), Loc Lnn +liver (1) | Loc Lnn (2), Liver (1), Tu-thr. into RA + lungs (1) | Loc Lnn (2), Liver (1), Liver + distant Lnn (1) | Loc Lnn (2), Loc Lnn + bone (1) | Loc muscle (1), Loc muscle + bone (1), dissem. (2) | ||

| N pathogenic variants: VHL, NF1, RET, SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, CHEK2, resp. | n.a. | 4, 3, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0 | n.a. | n.a. | 0, 0, 1, 1, 5, 1, 0, 1 | n.a. | 2, 0, 0, 0,0, 0, 3, 0 | - |

| FU duration, total (years) mean ± SD (range) | 14.4 ± 11.2 (1.3–35.4) | 15.5 ± 13.2 (0.4–32.7) | 7.7 ± 7.1 (1.2–21.2) | 7.8 ± 7.3 (2.0–19.6) | 7.7. ± 7.7 (1.7–26.9) | 3.6 ± 3.3 (0.7–9.1) | 31.0 ± 8.8 (17.8–41.1) | <0.0001 ** |

| FU with imaging (years), mean ± SD (range) | 2.7 ± 1.9 (0.7–6.4) | 6.7 ± 9.7 (0.4–29.6) | 1.8 ± 1.7 (0.6–5.9) | 7.6 ± 8.8 (1.9–17.7) | 4.5. ± 4.2 (0.3–10.4) | 1.1 ± 1.5 (0.3–3.7) | 6.9 ± 4.6 (1.6–11.7) | 0.2 |

| Ther after 1st OP, N (∆) | N = 9 (6pts) | N = 5 (4pts) | N = 7 (6pts) | N = 5 (3pts | N = 7 (4pts) | N = 6 (6pts) | N = 11 (2pts) | |

| - Additional surgery | 1(∆ +1), 1#(∆+ 2) | 1#(∆+1), 2(∆+2), 1#(∆+3) | 2#(∆+1), 1#(∆+3) | 2#(∆+2), 1(∆+3), 1#(∆+4) | 2(∆+1), 1(∆+3) | 1#(∆—1) | ||

| - 131MIBG | 1(∆—1), 2(∆+2), 1(∆+3), 1#(∆+4) | 1(∆+2) | 3(∆+1), 1(∆+2), 1#(∆+3) | 1#(∆+3) | 1(∆+1) | |||

| - 177Lu-DOTA | 1#(∆+7) | 1#(∆+8) | 1(∆+1) | 1#(∆+1), 1#(∆+4,+12) | ||||

| - External radiation | 1#(∆+2) | 1#(∆+2) | 1#(∆+8) | 1(+4) | 1#(∆—1,+1), 1#(∆+1,+11) | |||

| - Chemotherapy | 1#(∆—1), 1(∆+2) | 1#(∆+5) | 1#(∆+1), | |||||

| - SIRT | 1#(∆—1,+20) | |||||||

| Overall death, N (%) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (22.2) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (80.0) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0.69 * |

| Death of metast PPGL, N (%) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (50.0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (20.0) | 0.99 * |

| PreOP imaging, N pts (method) | 1 (1 DOPA) | 3 (1 MIBG, 2 DOPA) | 3 (3 MIBG) | 2 (1 FDG, 1 GaOTA) | 3 (2 MIBG, 1 DOPA) | 0 | 1 (1 MIBG) | 0.85 * |

| FU imaging, N pts (%) | 11 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | 4 (80.0) | 9 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 0.85 * |

| FU imaging studies, N | 46 | 43 | 20 | 17 | 39 | 17 | 63 | 0.003 ** |

| N FU imaging studies per pt, mean ± SD (range) | 4.6 ± 2.3 (2–9) | 4.8 ± 3.9 (1–13) | 2.2 ± 0.9 (1–4) | 3.4 ± 3.1 (0–7) | 6.6 ± 5.7 (1–19) | 2.1 ± 1.4 (1–5) | 13.2 ± 10.8 (2–24) | 0.0003 *** |

| -MIBG, N/in N pts (range per pt) | 12/7 (0–3) | 14/4 (0–11) | 13/9 (0–3) | 4/3 (0–2) | 6/4 (0–3) | 7/4 (0–3) | 3/3 (0–1) | |

| -DOPA, N/in N pts (range per pt) | 25/9 (0–8) | 28/8 (0–8) | 3/2 (0–2) | 9/4 (0–5) | 5/4 (0–2) | 6/5 (0–2) | 25/5 (0–20) | |

| -FDG, N/in N pts (range per pt) | 3/2 (0–2) | 0 | 2/2 (0–1) | 1/1 | 16/1 (0–16) | 2/1 (0–2) | 3/2 (0–2) | |

| -GaDOTA, N/in N pts (range per pt) | 6/4 (0–2) | 1/1 | 2/2 (0–1) | 3/1 (0–3) | 12/5 (0–4) | 2/1 (0–2) | 32/3 (0–21) |

| MIBG | F-DOPA | FDG | GaDOTA | p Value | p Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 57) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.72 (0.56–0.84) | 0.77 (0.63–0.87) | 0.75 (0.47–0.91) | 0.67 (0.47–0.82) | 0.81 | 0.34 |

| Lesion-based | 0.67 (0.63–0.71) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 0.98 (0.95–0.99) | 0.85 (0.81–0.88) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Imaging-based | 0.84 (0.76–0.89) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 0.93 (0.84–0.97) | 0.87 (0.80–0.92) | 0.33 | 0.64 |

| PCC (N = 30) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.81 (0.60–0.92) | 0.76 (0.55–0.89) | 0.75 (0.30–0.99) | 0.60 (0.31–0.83) | 0.66 | 0.35 |

| Lesion-based | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) | 0.96 (0.92–0.98) | 0.87 (0.71–0.95) | 0.74 (0.67–0.80) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Imaging-based | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.79 (0.70–0.86) | 0.78 (0.45–0.96) | 0.75 (0.53–0.89) | 0.20 | 0.69 |

| PGL (N = 22) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.64 (0.39–0.84) | 0.72 (0.49–0.88) | 1.0 (0.51–1.0) | 0.7 (0.40–0.89) | 0.58 | 0.90 |

| Lesion-based | 0.47 (0.40–0.56) | 0.87 (0.80–0.92) | 1.0 (0.98–1.0) | 0.92 (0.86–0.95) | <0.0001 | 0.29 |

| Imaging-based | 0.76 (0.61–0.87) | 0.87 (0.73–0.94) | 1.0 (0.92–1.0) | 0.79 (0.62–0.90) | 0.007 | 0.41 |

| HNPGL (N = 5) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.50 (0–09-0.91) | 1.0 (0.57–1.0) | 0.5 (0.09–0.91) | 0.75 (0.30–0.99) | 0.29 | 0.24 |

| Lesion-based | 0.24 (0.14–0.39) | 1.0 (0.96–1.0) | 0.98 (0.91–1.0) | 0.98 (0.92–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.24 |

| Imaging-based | 0.50 (0.19–0.81) | 1.0 (0.93–1.0) | 0.6 (0.23–0.93) | 0.95 (0.86–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.10 |

| MIBG | F-DOPA | FDG | GaDOTA | p Value | p Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 57) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.13 (0.01–0.47) | 0.78 (0.55–0.91) | 0.67 (0.12–0.98) | 1.0 (0.44–1.0) | 0.007 | 0.36 |

| Lesion-based | 0.11 (0.02–0.31) | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.42 (0.23–0.64) | 1.0 (0.61–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.42 |

| Imaging-based | 0.07 (0.01–0.32) | 0.86 (0.76–0.92) | 0.50 (0.09–0.91) | 1.0 (0.85–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.06 |

| PCC (N = 30) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0 (0.0–0.49) | 0.78 (0.45–0.89) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 0.04 | 0.60 |

| Lesion-based | 0 (0.0–0.23) | 0.85 (0.72–0.93) | 1.0 (0.65–1.0) | 1.0 (0.18–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.68 |

| Imaging-based | 0 (0.0–0.44) | 0.76 (0.61–0.87) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 0.002 | 0.65 |

| PGL (N = 22) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0 (0.0–0.56) | 0.19 (0.08–0.38) | 0 (0.0–0.95) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lesion-based | 0 (0.0–0.49) | 0.93 (0.79–0.99) | 0 (0.0–0.26) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Imaging-based | 0 (0.0–0.32) | 0.89 (0.67–0.98) | 0 (0.0–0.82) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| HNPGL (N = 5) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.18–1.0) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Lesion-based | 1.0 (0.18–1.0) | 1.0 (0.18–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.51–1.0) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Imaging-based | 1.0 (0.44–1.0) | 1.0 (0.85–1.0) | 1.0 (0.05–1.0) | 1.0 (0.94–1.0) | n.a. | n.a. |

| CON, all (N = 527) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.73 (0.57–0.85) | 0.98 (0.95–0.99) | 0.77 (0.70–0.82) | 0.98 (0.95–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.74 |

| Lesion-based | 0.71 (0.56–0.83) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 0.98 (0.95–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.25 |

| Imaging-based | 0.73 (0.57–0.85) | 0.97 (0.94–0.98) | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | 0.99 (0.97–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

| CON, adr. tu. (N = 201) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.28 (0.13–0.51) | 0.93 (0.85–0.97) | 0.65 (0.55–0.73) | 0.90 (0.74–0.96) | <0.0001 | 0.68 |

| Lesion-based | 0.70 (0.48–0.86) | 0.91 (0.83–0.95) | 0.65 (0.57–0.73) | 0.92 (0.79–0.97) | <0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Imaging-based | 0.72 (0.49–0.88) | 0.92 (0.85–0.96) | 0.68 (0.59–0.75) | 0.90 (0.82–0.95) | <0.0001 | 0.81 |

| CON, no adr. tu. (N = 326) | ||||||

| Patient-based | 0.74 (0.51–0.88) | 0.99 (0.97–1.0) | 0.97 (0.89–0.99) | 1.0 (0.98–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Lesion-based | 0.74 (0.51–0.88) | 0.99 (0.97–1.0) | 0.97 (0.89–0.99) | 1.0 (0.98–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Imaging-based | 0.74 (0.51–0.88) | 1.0 (0.97–1.0) | 0.98 (0.94–1.0) | 1.0 (0.99–1.0) | <0.0001 | 0.28 |

| Sensitivity, Lesion-Based | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F-DOPA | GaDOTA | p-Value | |

| all pts, all meta | 0.94 | 0.85 | <0.0001 |

| all PCC, all meta | 0.96 | 0.74 | <0.0001 |

| all pts, bone meta | 0.97 | 0.79 | <0.0001 |

| all PCC, bone meta | 1.0 | 0.21 | <0.0001 |

| all PGL, bone meta | 0.86 | 1.0 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scheuba, A.; Kulterer, O.C.; Lehner, R.; Rybiczka-Tešulov, M.; Esterbauer, H.; Raber, W. Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Diagnostic Performance of Functional Imaging (18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA-, 68Ga-DOTA- and 18F-Fluoro-Deoxyglucose-Based PET/CT) and of 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in 57 Patients and 527 Controls During Long-Term Follow-Up. Cancers 2025, 17, 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233855

Scheuba A, Kulterer OC, Lehner R, Rybiczka-Tešulov M, Esterbauer H, Raber W. Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Diagnostic Performance of Functional Imaging (18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA-, 68Ga-DOTA- and 18F-Fluoro-Deoxyglucose-Based PET/CT) and of 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in 57 Patients and 527 Controls During Long-Term Follow-Up. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233855

Chicago/Turabian StyleScheuba, Andreas, Oana Cristina Kulterer, Reinhard Lehner, Mateja Rybiczka-Tešulov, Harald Esterbauer, and Wolfgang Raber. 2025. "Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Diagnostic Performance of Functional Imaging (18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA-, 68Ga-DOTA- and 18F-Fluoro-Deoxyglucose-Based PET/CT) and of 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in 57 Patients and 527 Controls During Long-Term Follow-Up" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233855

APA StyleScheuba, A., Kulterer, O. C., Lehner, R., Rybiczka-Tešulov, M., Esterbauer, H., & Raber, W. (2025). Metastatic Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma: Diagnostic Performance of Functional Imaging (18F-Fluoro-L-DOPA-, 68Ga-DOTA- and 18F-Fluoro-Deoxyglucose-Based PET/CT) and of 123I-MIBG Scintigraphy in 57 Patients and 527 Controls During Long-Term Follow-Up. Cancers, 17(23), 3855. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233855