Clinical and Molecular Characterization of KRAS-Mutated Renal Cell Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort Selection

2.2. Pathologic Evaluation

2.3. Genomic Characterization and Analysis

2.4. Transcriptomic Characterization and Analysis

2.5. Immunohistochemistry Evaluation

3. Results

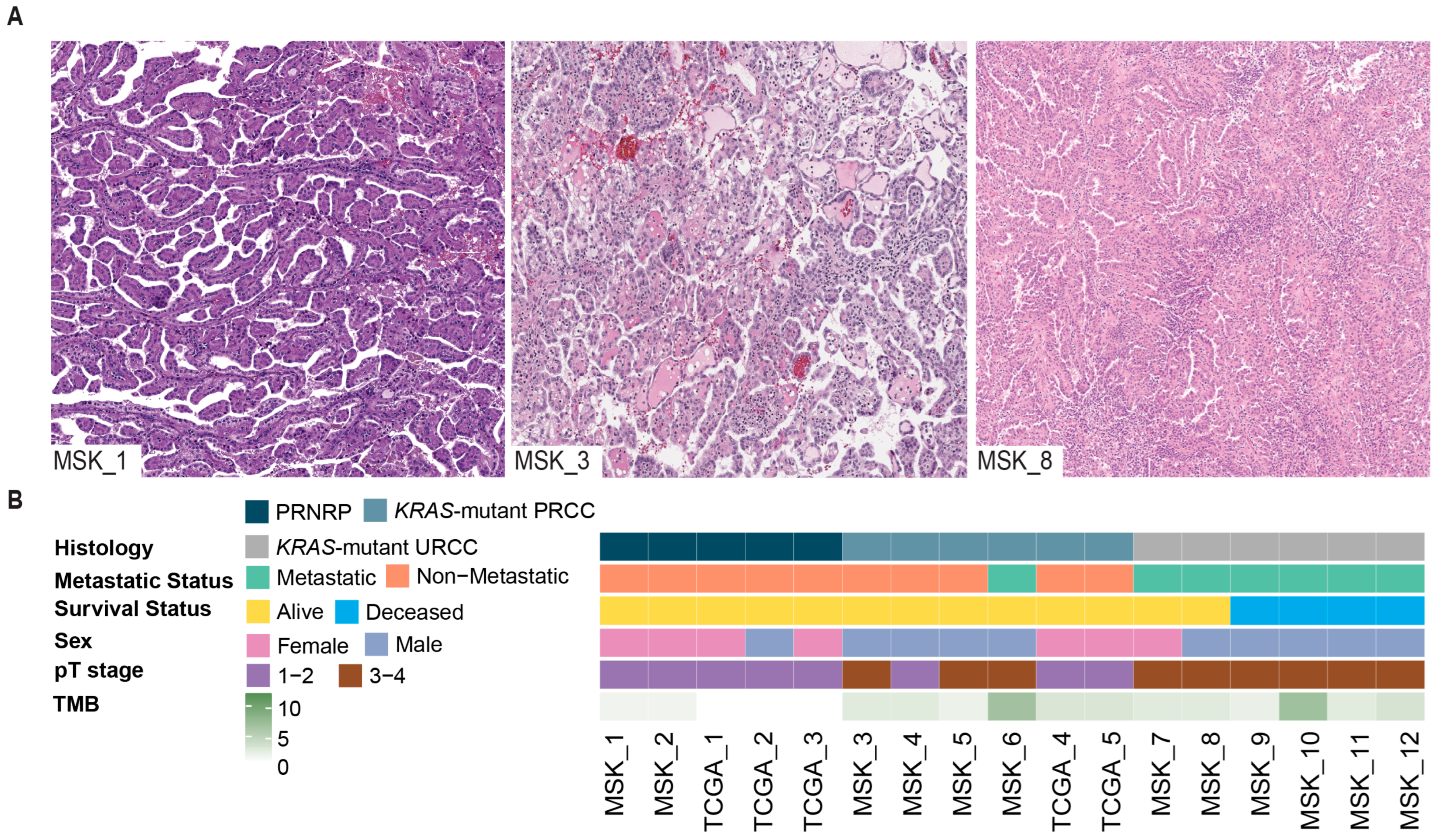

3.1. Clinicopathologic Features

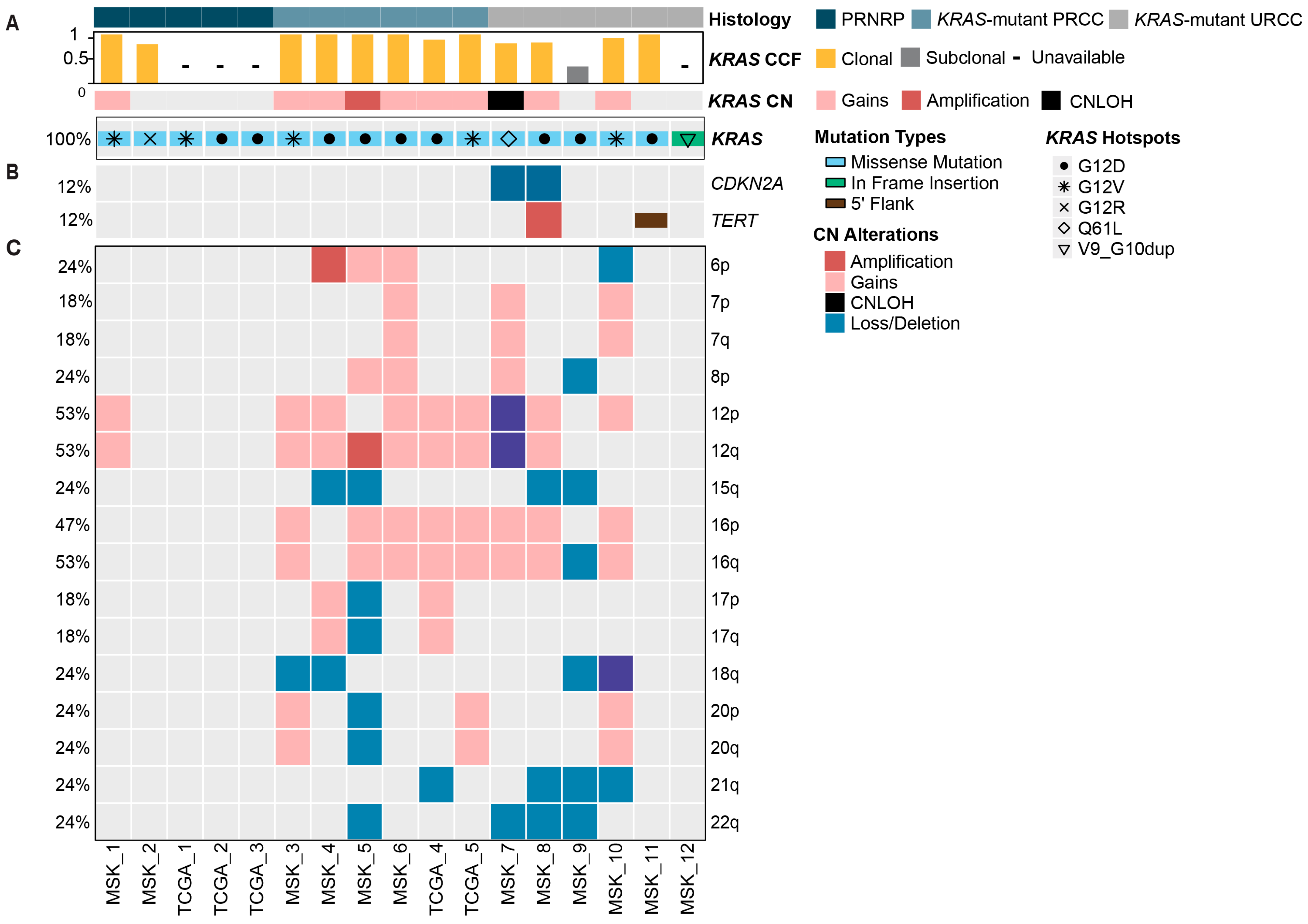

3.2. Genomic Characterization and Analysis

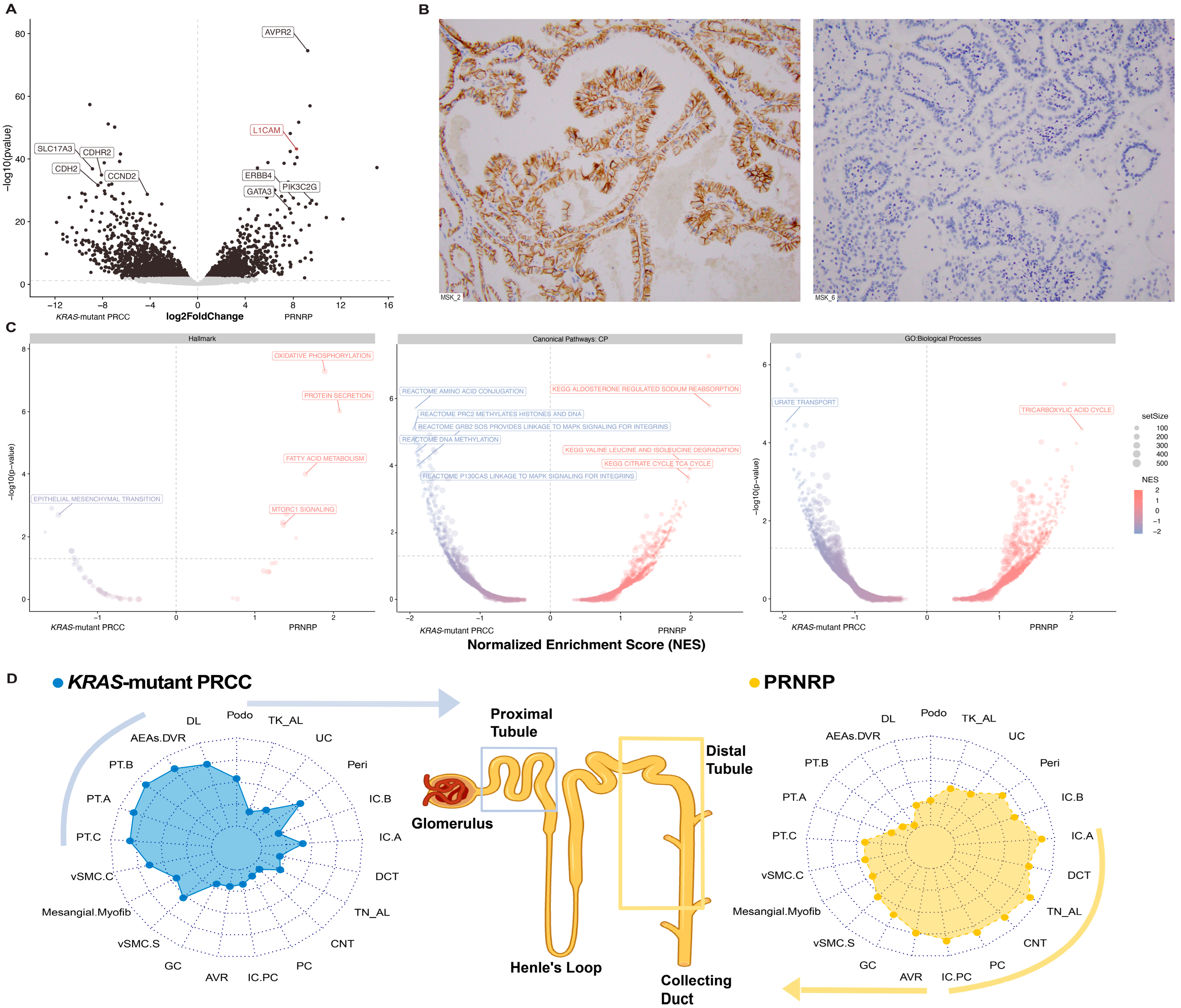

3.3. Transcriptomic Characterization and Analysis

3.4. Immunohistochemistry Correlation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wu, K.; Shi, L. The Roles of KRAS in Cancer Metabolism, Tumor Microenvironment and Clinical Therapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S.; Chu, Q. KRAS Mutations in Solid Tumors: Characteristics, Current Therapeutic Strategy, and Potential Treatment Exploration. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, R.B. A Single Inhibitor for All KRAS Mutations. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Zhu, W.; Fu, H.; Cao, F.; Wang, S.; Zhou, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, D.; Fan, S.; Hu, Z. Frequent KRAS Mutations in Oncocytic Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Inverted Nuclei. Histopathology 2020, 76, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidy, K.I.; Eble, J.N.; Nassiri, M.; Cheng, L.; Eldomery, M.K.; Williamson, S.R.; Sakr, W.A.; Gupta, N.; Hassan, O.; Idrees, M.T.; et al. Recurrent KRAS Mutations in Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidy, K.I.; Saleeb, R.M.; Trpkov, K.; Williamson, S.R.; Sangoi, A.R.; Nassiri, M.; Hes, O.; Montironi, R.; Cimadamore, A.; Acosta, A.M.; et al. Recurrent KRAS Mutations Are Early Events in the Development of Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.W.; Wang, P.; Wanjari, P.; Wuori, D.; Paik, J.; Pytel, P.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Tjota, M.Y.; Antic, T. Renal Tumorigenesis via RAS/RAF/MAPK Pathway Alterations Beyond Papillary Renal Neoplasm With Reverse Polarity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2025, 49, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Cho, Y.M.; Kim, G.H.; Kee, K.H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, C. Recurrent KRAS Mutations Identified in Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity—A Comparative Study with Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trpkov, K.; Hes, O.; Williamson, S.R.; Adeniran, A.J.; Agaimy, A.; Alaghehbandan, R.; Amin, M.B.; Argani, P.; Chen, Y.-B.; Cheng, L.; et al. New Developments in Existing WHO Entities and Evolving Molecular Concepts: The Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) Update on Renal Neoplasia. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1392–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeb, R.M.; Brimo, F.; Farag, M.; Rompré-Brodeur, A.; Rotondo, F.; Beharry, V.; Wala, S.; Plant, P.; Downes, M.R.; Pace, K.; et al. Toward Biological Subtyping of Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma with Clinical Implications Through Histologic, Immunohistochemical, and Molecular Analysis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyozawa, D.; Kohashi, K.; Takamatsu, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Eto, M.; Iwasaki, T.; Motoshita, J.; Shimokama, T.; Kinjo, M.; Oshiro, Y.; et al. Morphological, Immunohistochemical, and Genomic Analyses of Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity. Hum. Pathol. 2021, 112, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidy, K.I.; Eble, J.N.; Cheng, L.; Williamson, S.R.; Sakr, W.A.; Gupta, N.; Idrees, M.T.; Grignon, D.J. Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.H.; Melloni, G.E.M.; Gulhan, D.C.; Park, P.J.; Haigis, K.M. The Origins and Genetic Interactions of KRAS Mutations Are Allele- and Tissue-Specific. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyozawa, D.; Iwasaki, T.; Takamatsu, D.; Kohashi, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Fukuchi, G.; Eto, M.; Yamashita, M.; Oda, Y. Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity Has Low Frequency of Alterations in Chromosomes 7, 17, and Y. Virchows Arch. 2024, 485, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Narayanan, S.P.; Mannan, R.; Raskind, G.; Wang, X.; Vats, P.; Su, F.; Hosseini, N.; Cao, X.; Kumar-Sinha, C.; et al. Single-Cell Analyses of Renal Cell Cancers Reveal Insights into Tumor Microenvironment, Cell of Origin, and Therapy Response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2103240118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.T.; Mitchell, T.N.; Zehir, A.; Shah, R.H.; Benayed, R.; Syed, A.; Chandramohan, R.; Liu, Z.Y.; Won, H.H.; Scott, S.N.; et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT). J. Mol. Diagn. 2015, 17, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Phillips, S.; Kundra, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, J.E.; Yaeger, R.; Soumerai, T.; Nissan, M.H.; et al. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, I.; Kundra, R.; Mastrogiacomo, B.; Tran, T.N.; Sikina, L.; Mazor, T.; Li, X.; Ochoa, A.; Zhao, G.; Lai, B.; et al. Analysis and Visualization of Longitudinal Genomic and Clinical Data from the AACR Project GENIE Biopharma Collaborative in cBioPortal. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 3861–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, R.; Seshan, V.E. FACETS: Allele-Specific Copy Number and Clonal Heterogeneity Analysis Tool for High-Throughput DNA Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, A.P.; Ferretti, V.; Agrawal, S.; An, M.; Angelakos, J.C.; Arya, R.; Bajari, R.; Baqar, B.; Barnowski, J.H.B.; Burt, J.; et al. The NCI Genomic Data Commons. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, W. RSeQC: Quality Control of RNA-Seq Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2184–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, K.R.; Armstrong, J.; Barber, G.P.; Casper, J.; Clawson, H.; Diekhans, M.; Dreszer, T.R.; Fujita, P.A.; Guruvadoo, L.; Haeussler, M.; et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database: 2015 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D670–D681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Huber, W.; Pagès, H.; Aboyoun, P.; Carlson, M.; Gentleman, R.; Morgan, M.T.; Carey, V.J. Software for Computing and Annotating Genomic Ranges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1003118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, M.S.; Shukla, S.A.; Wu, C.J.; Getz, G.; Hacohen, N. Molecular and Genetic Properties of Tumors Associated with Local Immune Cytolytic Activity. Cell 2015, 160, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Subramanian, A.; Pinchback, R.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Tamayo, P.; Mesirov, J.P. Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P. The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbie, D.A.; Tamayo, P.; Boehm, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Moody, S.E.; Dunn, I.F.; Schinzel, A.C.; Sandy, P.; Meylan, E.; Scholl, C.; et al. Systematic RNA Interference Reveals That Oncogenic KRAS-Driven Cancers Require TBK1. Nature 2009, 462, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M.; Chen, J.-F.; Jungbluth, A.; Koutzaki, S.; Palmer, M.B.; Al-Ahmadie, H.A.; Fine, S.W.; Gopalan, A.; Sarungbam, J.; Sirintrapun, S.J.; et al. L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule (L1CAM) Expression and Molecular Alterations Distinguish Low-Grade Oncocytic Tumor from Eosinophilic Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 37, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Papillary Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-B.; Xu, J.; Skanderup, A.J.; Dong, Y.; Brannon, A.R.; Wang, L.; Won, H.H.; Wang, P.I.; Nanjangud, G.J.; Jungbluth, A.A.; et al. Molecular Analysis of Aggressive Renal Cell Carcinoma with Unclassified Histology Reveals Distinct Subsets. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.; Brown, G.; Wallin, C.; Tatusova, T.; Pruitt, K.; Maglott, D. Gene Help: Integrated Access to Genes of Genomes in the Reference Sequence Collection; National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bielski, C.M.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Gadiya, M.; Hanrahan, A.J.; Won, H.H.; Chang, M.T.; Jonsson, P.; Penson, A.V.; Gorelick, A.; Harris, C.; et al. Widespread Selection for Oncogenic Mutant Allele Imbalance in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 852–862.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, D.; Eriksson, P.; Krawczyk, K.; Nilsson, H.; Hansson, J.; Veerla, S.; Sjölund, J.; Höglund, M.; Johansson, M.E.; Axelson, H. Cell-Type-Specific Gene Programs of the Normal Human Nephron Define Kidney Cancer Subtypes. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 1476–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, C.; Lu, X. Epithelial Cell Polarity: A Major Gatekeeper against Cancer? Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, F.; Yu, J.; Huang, J.; Hong, Y.; Wu, S.; Pan, D. The Apical Transmembrane Protein Crumbs Functions as a Tumor Suppressor That Regulates Hippo Signaling by Binding to Expanded. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10532–10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.A.; Myers, P.J.; Adair, S.J.; Pitarresi, J.R.; Sah-Teli, S.K.; Campbell, L.A.; Hart, W.S.; Barbeau, M.C.; Leong, K.; Seyler, N.; et al. A Histone Methylation–MAPK Signaling Axis Drives Durable Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Hypoxic Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1764–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, V.F.; Trpkov, K.; Van Der Kwast, T.; Rotondo, F.; Hamdani, M.; Saleeb, R. Papillary Renal Neoplasm with Reverse Polarity Is Biologically and Clinically Distinct from Eosinophilic Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol. Int. 2024, 74, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, M.C.; Er, E.E.; Blenis, J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR Pathways: Cross-Talk and Compensation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, Y.; Ito, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Kimura, R.; Tan, T.Z.; Yamaguchi, R.; Ebi, H. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is a Cause of Both Intrinsic and Acquired Resistance to KRAS G12C Inhibitor in KRAS G12C–Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5962–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez Sanmiguel, A.; Khandwala, Y.S.; Fengshen, K.; Dawidek, M.; Tse, E.; Barbakoff, D.; Posada Calderon, L.; Carlo, M.I.; Coleman, J.; Russo, P.; et al. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of KRAS-Mutated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233832

Lopez Sanmiguel A, Khandwala YS, Fengshen K, Dawidek M, Tse E, Barbakoff D, Posada Calderon L, Carlo MI, Coleman J, Russo P, et al. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of KRAS-Mutated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233832

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez Sanmiguel, Andrea, Yash S. Khandwala, Kuo Fengshen, Mark Dawidek, Ethan Tse, Daniel Barbakoff, Lina Posada Calderon, Maria I. Carlo, Jonathan Coleman, Paul Russo, and et al. 2025. "Clinical and Molecular Characterization of KRAS-Mutated Renal Cell Carcinoma" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233832

APA StyleLopez Sanmiguel, A., Khandwala, Y. S., Fengshen, K., Dawidek, M., Tse, E., Barbakoff, D., Posada Calderon, L., Carlo, M. I., Coleman, J., Russo, P., Tickoo, S. K., Reuter, V. E., Reznik, E., Chen, Y.-B., & Hakimi, A. A. (2025). Clinical and Molecular Characterization of KRAS-Mutated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers, 17(23), 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233832