Deriving Real-World Evidence from Non-English Electronic Medical Records in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Using Large Language Models

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To verify established clinicopathological prognostic factors in a population in Moscow.

- To look into the clinico-morphological traits of the suggested LPP subgroup, with an emphasis on how patient outcomes are impacted by low PR expression, poor differentiation, and high proliferation.

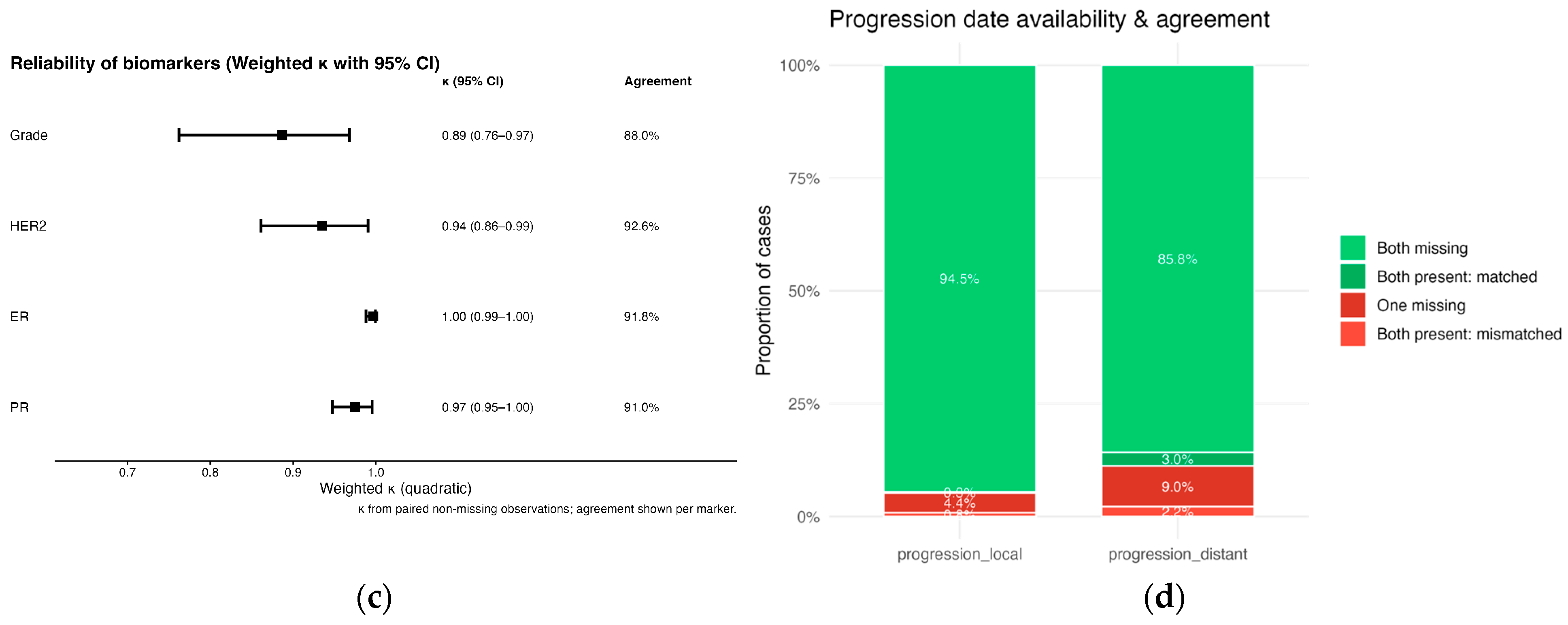

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

- Female sex;

- Age ≥ 18 years at diagnosis;

- ICD-10 code C50.X recorded in the EMR;

- Date of pathologically confirmed diagnosis between 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019;

- Non-empty target fields (“disease history”, “extended diagnosis”, “pathology reports”).

2.2. Raw-Text Dataset Construction

2.3. Prompt Engineering and Large Language Model Extraction

- Multiple primary cancers: If any text indicated an additional malignancy, both annotators (see below) and the LLM recorded “yes” for multiple cancers and left all other tumor-specific variables blank to avoid bias for the model as it might increase context complexity and model excluded patients with “yes” annotation from final dataset automatically.

- Repeated events: For local or distant progression, the earliest documented date was extracted.

- Clinically incorrect values: Out-of-range values (e.g., Ki-67 > 100 %, grade > 3, ER > 8) were retained “as written” during extraction and removed during a rule-based post-filtering step in R (see below).

- Missing values: Blanks were preserved in the final dataset generated by the LLM. During validation, a missing–missing match was scored as concordant to avoid penalizing the model for absent source data.

- Extract full-text data per patient from an .xlsx raw-data document;

- Input a designed prompt with each patient data;

- Extract each generated JSON object with structured patient data;

- Parse each JSON object;

- Generate a human-readable .docx intermediate report per patient for auditability;

- Appended the parsed values to a new Excel file.

2.4. Validation of LLM Extraction

2.5. Post-Processing and Data Cleaning

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Clinical Data

2.7. Definition of «LPP» Subtype

2.8. Classification Rules for Luminal A, Luminal B (HER2−), and LPP

3. Results

3.1. LLM Validation Results

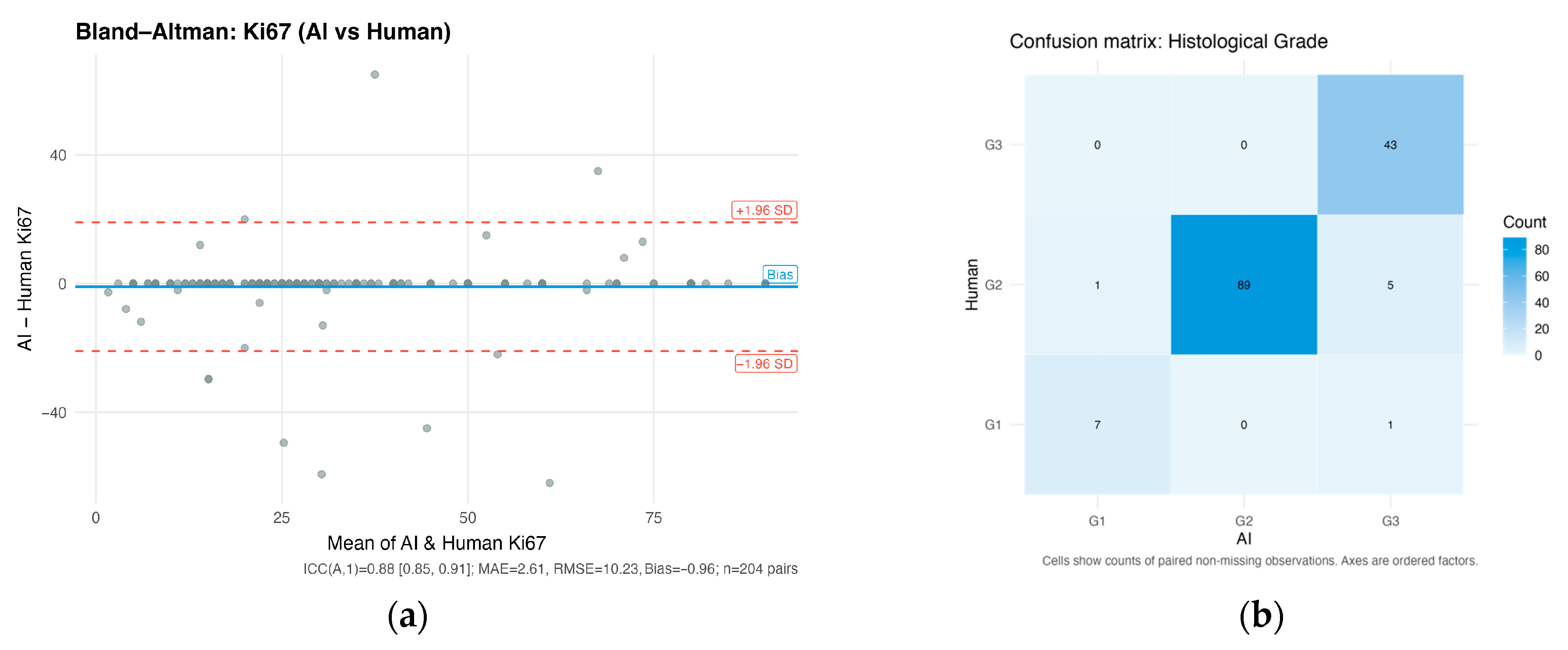

3.1.1. Ki-67 Proliferation Index

3.1.2. Histological Grade

3.1.3. Receptor Status for ER, PR, and HER2

3.1.4. Progression Dates

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Cutoff Evaluation

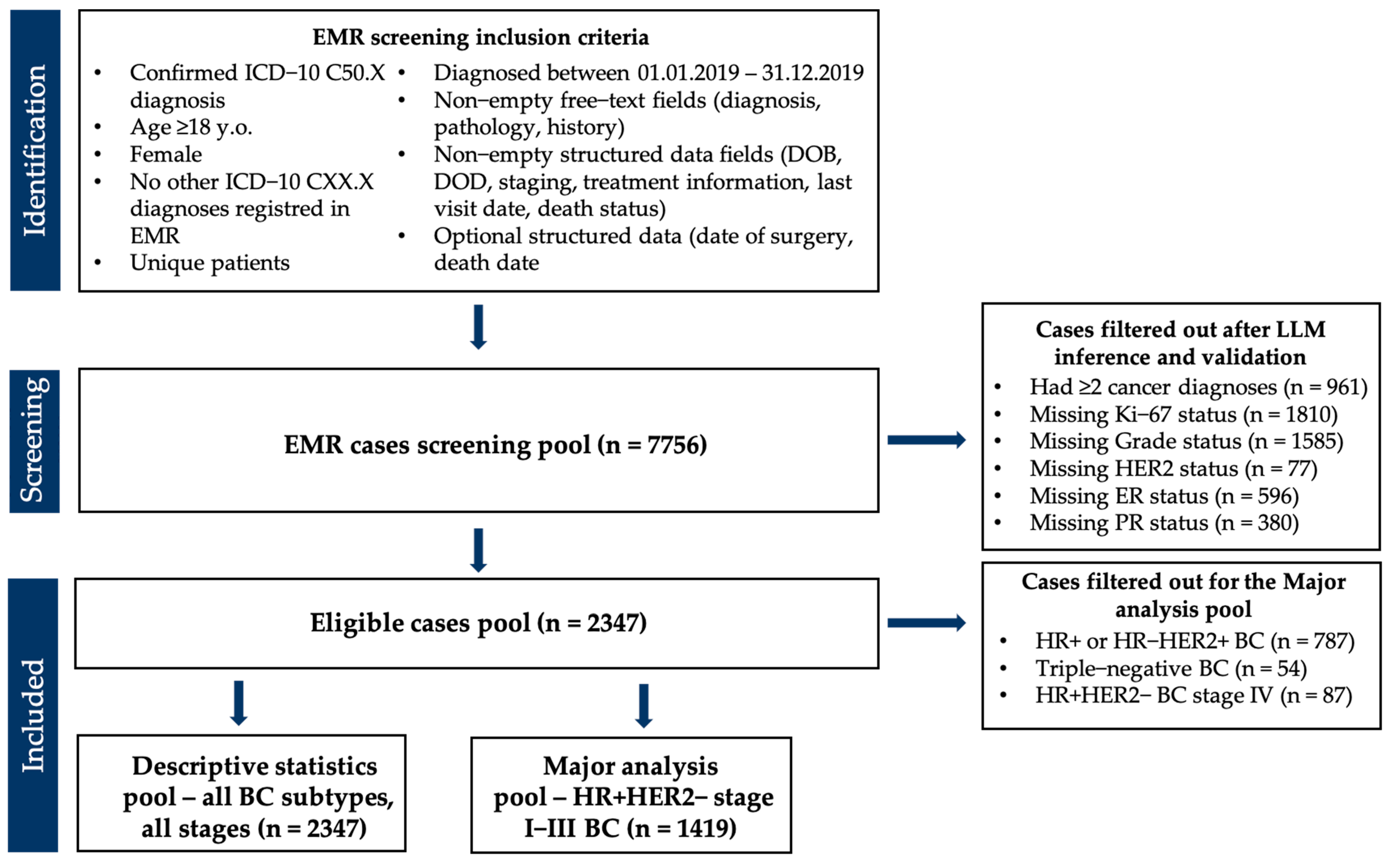

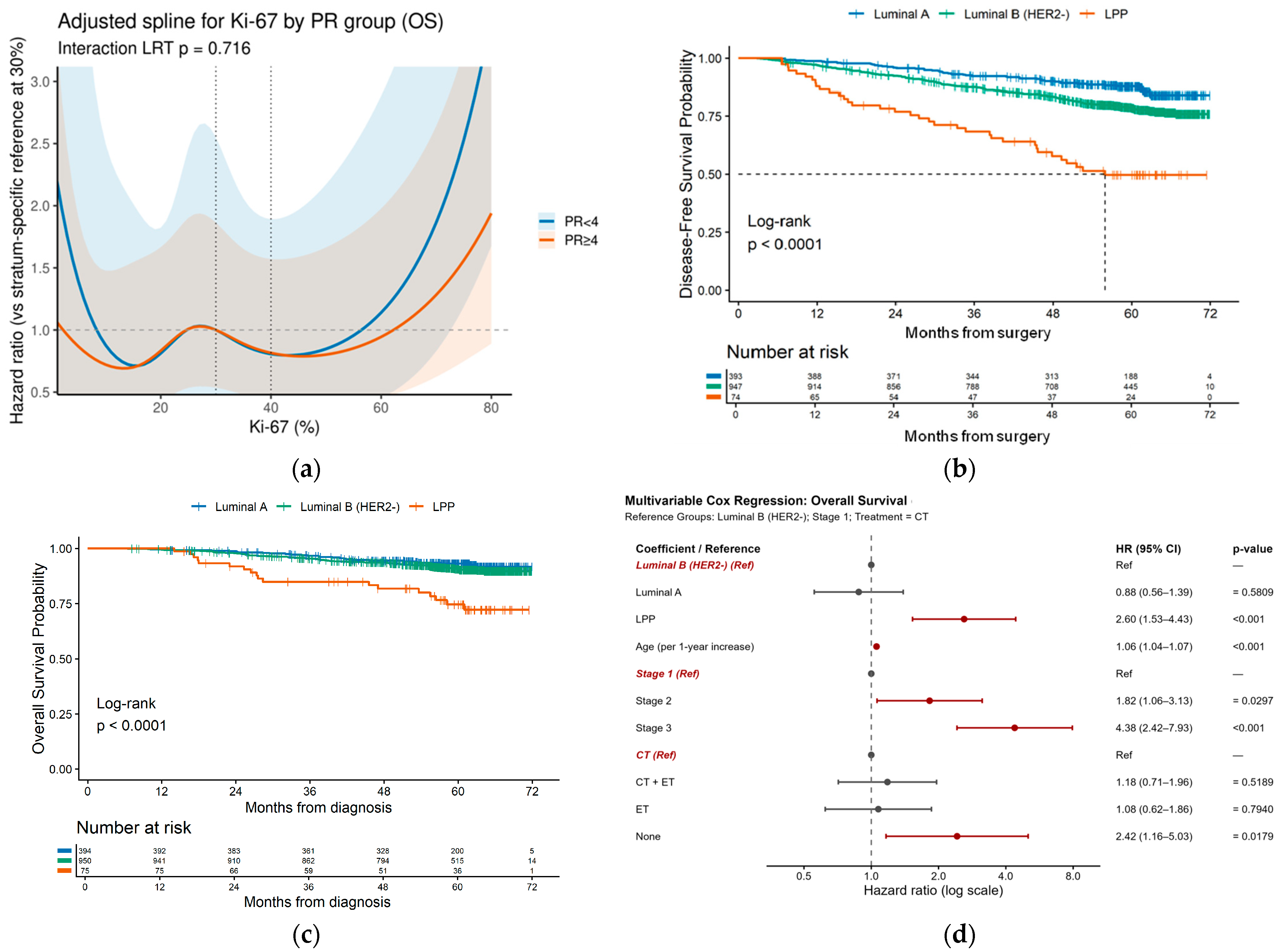

3.3. Survival Analysis

3.3.1. Univariate Survival Analysis

3.3.2. «Luminal B Poor-Prognosis» Subgroup Identification

4. Discussion

4.1. LLM Performance in Data Extraction

4.2. Clinical Findings and the LPP Subtype

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast cancer |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| EMR | Electronic medical records |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HR+/HER2 | Hormone-positive HER2-negative |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LLM | Large language model |

| NAT | Neoadjuvant treatment |

| AT | Adjuvant treatment |

| ET | Endocrine therapy |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| LPP | Luminal B poor-prognosis |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estim ates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer of the Breast (Female)—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Howlader, N.; Cronin, K.A.; Kurian, A.W.; Andridge, R. Differences in Breast Cancer Survival by Molecular Subtypes in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2018, 27, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo, E.M.; Ramirez, A.O.; Cueto, J.; Law, E.H.; Situ, A.; Cameron, C.; Samjoo, I.A. Risk of Recurrence among Patients with HR-Positive, HER2-Negative, Early Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Edinb. Scotl. 2021, 57, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of Chemotherapy and Hormonal Therapy for Early Breast Cancer on Recurrence and 15-Year Survival: An Overview of the Randomised Trials. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2005, 365, 1687–1717. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colleoni, M.; Sun, Z.; Price, K.N.; Karlsson, P.; Forbes, J.F.; Thürlimann, B.; Gianni, L.; Castiglione, M.; Gelber, R.D.; Coates, A.S.; et al. Annual Hazard Rates of Recurrence for Breast Cancer During 24 Years of Follow-Up: Results From the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Gray, R.; Braybrooke, J.; Davies, C.; Taylor, C.; McGale, P.; Peto, R.; Pritchard, K.I.; Bergh, J.; Dowsett, M.; et al. 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence after Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Swartz, M.D.; Zhao, H.; Kapadia, A.S.; Lai, D.; Rowan, P.J.; Buchholz, T.A.; Giordano, S.H. Hazard of Recurrence among Women after Primary Breast Cancer Treatment--a 10-Year Follow-up Using Data from SEER-Medicare. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2012, 21, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-J.; Yu, Y.; Hou, X.-W.; Chi, J.-R.; Ge, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.-C. The Prognostic Value of Node Status in Different Breast Cancer Subtypes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 4563–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, K.M.; Peachey, J.R.; Method, M.; Grimes, B.R.; Brown, J.; Saverno, K.; Sugihara, T.; Cui, Z.L.; Lee, K.T. A Real-World US Study of Recurrence Risks Using Combined Clinicopathological Features in HR-Positive, HER2-Negative Early Breast Cancer. Future Oncol. Lond. Engl. 2022, 18, 2667–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abstract P2-10-07: Practice Patterns and Survival Analysis of Early-Stage HER-Negative Breast Cancers with Low and Intermediate Levels of Hormone Receptor Expression: A 2018-2020 US National Cancer Database Analysis | Clinical Cancer Research | American Association for Cancer Research. Available online: https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/31/12_Supplement/P2-10-07/753910/Abstract-P2-10-07-Practice-patterns-and-survival (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Carvalho, G.D.S.; Gomes, D.M.; Bretas, G.D.O.; Teixeira, V.B.G.; Bines, J. Late Breast Cancer Recurrence Prediction: The Role of CTS5 and Progesterone Receptor Status. Breast Cancer Dove Med. Press 2025, 17, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravaccini, S.; Bronte, G.; Scarpi, E.; Ravaioli, S.; Maltoni, R.; Mangia, A.; Tumedei, M.M.; Puccetti, M.; Serra, P.; Gianni, L.; et al. The Impact of Progesterone Receptor Expression on Prognosis of Patients with Rapidly Proliferating, Hormone Receptor-Positive Early Breast Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of the IBIS 3 Trial. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835919888999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.M.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, I.; Lee, S.K.; Yu, J.; Kim, J.-E.; Kang, B.; Lee, J.E.; Nam, S.J.; Kim, S.W. Only Estrogen Receptor “Positive” Is Not Enough to Predict the Prognosis of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 172, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, R.; Osako, T.; Okumura, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Toyozumi, Y.; Arima, N. Ki-67 as a Prognostic Marker According to Breast Cancer Subtype and a Predictor of Recurrence Time in Primary Breast Cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010, 1, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, M.; Chaudry, S.S.; Khalid Sheikh, A.; Khan, N.; Khattak, A.; Akbar, A.; Tanwani, A.K.; Khaliq, T.; Malik, M.F.A.; Riaz, S.K. Comparison of Different Molecular Subtypes with 14% Ki-67 Cut-off Threshold in Breast Cancer Patients of Pakistan- An Indication of Poor Prognosis. Arch. Iran. Med. 2021, 24, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Liu, Y.-B.; She, T.; Liu, X.-L. The Role of Ki-67 in HR+/HER2- Breast Cancer: A Real-World Study of 956 Patients. Breast Cancer Dove Med. Press 2024, 16, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, A.; Carlino, F.; Buono, G.; Antoniol, G.; Famiglietti, V.; De Angelis, C.; Carrano, S.; Piccolo, A.; De Vita, F.; Ciardiello, F.; et al. Prognostic Relevance of Progesterone Receptor Levels in Early Luminal-Like HER2 Negative Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Retrospective Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 813462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ding, K.; Qian, H.; Yu, X.; Zou, D.; Yang, H.; Mo, W.; He, X.; Zhang, F.; Qin, C.; et al. Impact on Survival of Estrogen Receptor, Progesterone Receptor and Ki-67 Expression Discordance Pre- and Post-Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, B.; Waskom, M.; Blarre, A.; Kelly, J.; Krismer, K.; Nemeth, S.; Gippetti, J.; Ritten, J.; Harrison, K.; Ho, G.; et al. Approach to Machine Learning for Extraction of Real-World Data Variables from Electronic Health Records. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1180962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Kim, K.; Shin, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, T.-J. Advancements in Electronic Medical Records for Clinical Trials: Enhancing Data Management and Research Efficiency. Cancers 2025, 17, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, M.-P.; Law, J.H.; Le, L.W.; Li, J.J.N.; Zahir, S.; Nirmalakumar, S.; Sung, M.; Pettengell, C.; Aviv, S.; Chu, R.; et al. Automating Access to Real-World Evidence. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, F.; Hsu, M.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Jian, W.-S. Using Generative AI to Extract Structured Information from Free Text Pathology Reports. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, D.M.; Rong, R.; Nezafati, K.; Treager, C.; Chi, Z.; Wang, S.; Cheng, X.; Guo, Y.; Klesse, L.J.; et al. A Critical Assessment of Using ChatGPT for Extracting Structured Data from Clinical Notes. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehandru, N.; Miao, B.Y.; Almaraz, E.R.; Sushil, M.; Butte, A.J.; Alaa, A. Evaluating Large Language Models as Agents in the Clinic. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veen, D.; Van Uden, C.; Blankemeier, L.; Delbrouck, J.-B.; Aali, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Pareek, A.; Polacin, M.; Reis, E.P.; Seehofnerová, A.; et al. Adapted Large Language Models Can Outperform Medical Experts in Clinical Text Summarization. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omiye, J.A.; Gui, H.; Rezaei, S.J.; Zou, J.; Daneshjou, R. Large Language Models in Medicine: The Potentials and Pitfalls: A Narrative Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Okuhara, T.; Chang, X.; Shirabe, R.; Nishiie, Y.; Okada, H.; Kiuchi, T. Performance of ChatGPT Across Different Versions in Medical Licensing Examinations Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e60807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Duan, L.; Xu, S.; Chi, L.; Sheng, D. Performance of Large Language Models in the Non-English Context: Qualitative Study of Models Trained on Different Languages in Chinese Medical Examinations. JMIR Med. Inform. 2025, 13, e69485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moëll, B.; Farestam, F.; Beskow, J. Swedish Medical LLM Benchmark: Development and Evaluation of a Framework for Assessing Large Language Models in the Swedish Medical Domain. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1557920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, N.; Schramm, F.; Haggenmüller, S.; Kather, J.N.; Hetz, M.J.; Wies, C.; Michel, M.S.; Wessels, F.; Brinker, T.J. Large Language Model Use in Clinical Oncology. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheligeer, K.; Wu, G.; Laws, A.; Quan, M.L.; Li, A.; Brisson, A.-M.; Xie, J.; Xu, Y. Validation of Large Language Models for Detecting Pathologic Complete Response in Breast Cancer Using Population-Based Pathology Reports. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasanella, S.; Leonardi, E.; Cantaloni, C.; Eccher, C.; Bazzanella, I.; Aldovini, D.; Bragantini, E.; Morelli, L.; Cuorvo, L.; Ferro, A.; et al. Proliferative Activity in Human Breast Cancer: Ki-67 Automated Evaluation and the Influence of Different Ki-67 Equivalent Antibodies. Diagn. Pathol. 2011, 6, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Waqas, A.; Venkatesan, K.; Ullah, E.; Khan, A.; Khalil, F.; Chen, W.-S.; Ozturk, Z.G.; Saeed-Vafa, D.; Bui, M.M.; et al. Employing Consensus-Based Reasoning with Locally Deployed LLMs for Enabling Structured Data Extraction from Surgical Pathology Reports. MedRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Unell, A.; Chen, B.; Fries, J.A.; Alsentzer, E.; Koyejo, S.; Shah, N. TIMER: Temporal Instruction Modeling and Evaluation for Longitudinal Clinical Records. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuner, Ö.; Stubbs, A.; Sun, W. Chronology of Your Health Events: Approaches to Extracting Temporal Relations from Medical Narratives. J. Biomed. Inform. 2013, 46, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokcu, Ş.; Ali-Çaparlar, M.; Çetindağ, Ö.; Hakseven, M.; Eroğlu, A. Prognostic value of KI-67 proliferation index in luminal breast cancers. Cir. Cir. 2023, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumuş, A.; Döngelli, H.; Semiz, H.; Keskinkılıç, M.; Hamitoğlu, B.; Yavuzşen, T. The prognostic value of platelet count and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, Ki-67, and Nottingham indexes in early-stage breast cancer. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2025, 71, e20250067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, S.; Rheinstein, P.H. Increased Survival of Women with Luminal Breast Cancer and Progesterone Receptor Immunohistochemical Expression of Greater than 10%. Cancer 2023, 129, 2103–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimukai, A.; Yagi, T.; Yanai, A.; Miyagawa, Y.; Enomoto, Y.; Murase, K.; Imamura, M.; Takatsuka, Y.; Sakita, I.; Hatada, T.; et al. High Ki-67 Expression and Low Progesterone Receptor Expression Could Independently Lead to a Worse Prognosis for Postmenopausal Patients With Estrogen Receptor-Positive and HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2015, 15, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, M.M.; Pagani, O.; Francis, P.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Walley, B.A.; Kammler, R.; Dell’Orto, P.; Russo, L.; Szőke, J.; Doimi, F.; et al. Predictive Value and Clinical Utility of Centrally-Assessed ER, PgR and Ki-67 to Select Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Early Breast Cancer: TEXT and SOFT Trials. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 154, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomssen, C.; Balic, M.; Harbeck, N.; Gnant, M.S. Gallen/Vienna 2021: A Brief Summary of the Consensus Discussion on Customizing Therapies for Women with Early Breast Cancer. Breast Care 2021, 16, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, G.F.; Pagani, O.; Regan, M.M.; Walley, B.A.; Francis, P.A. Adjuvant Abemaciclib Combined with Endocrine Therapy for High-Risk Early Breast Cancer: Updated Efficacy and Ki-67 Analysis from the monarchE Study. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2022, 33, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Expected Format | Examples Supplied in Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Ki-67 | numeric (%) | “Ki-67 = 32%” → 32 |

| ER (Allred) | integer 0–8 | “ER Allred 7/8” → 7 |

| PR (Allred) | integer 0–8 | “PR Allred 5” → 5 |

| HER2 IHC | categorical: 0, 1+, 2+, 3+ | “HER2 IHC 3+” → 3+ |

| grade | G1/G2/G3 | “grade 2” → G2 |

| local relapse date | dd.mm.yyyy | “local recurrence 14 March 2022” |

| distant relapse date | dd.mm.yyyy | “bone mts 9 November 2021” |

| multiple primary cancers | yes/no | prompt rule-based |

| Characteristics | Overall Cohort (n = 2347) | HR+/HER2− Stage I–III Cohort (n = 1419) |

|---|---|---|

| time of observation | 1 January 2019–28 February 2025 | |

| median age at diagnosis | 60.8 years (range 23.7–95.0) | 61.3 years (range 24.1–99.0) |

| median follow-up | 61.5 months | 61.6 months |

| stage | I—711 (29.9%) II—1015 (43.2%) III—471 (20.2%) IV—150 (6.7%) | I—497 (35.0%) II—631 (44.5%) III—291 (20.5%) |

| molecular subtypes | Luminal A– 409 (17.4%) Luminal B (HER2−)—1097 (46.7%) Luminal B (HER2+)—698 (29.8%) HR-HER2+—89 (3.8%) Triple negative—54 (2.4%) | Luminal A—394 (27.8%) Luminal B (HER2−)—1025 (72.2%) |

| median Ki-67 | 24 (IQR 15–35) | 25 (IQR 16–35) |

| ER | <5—215 (9.1%) ≥5—2132 (90.9%) | <5—32 (2.3%) ≥5—1387 (97.7%) |

| PR | <4—498 (21.2%) ≥4—1849 (78.8%) | <4—200 (14.1%) ≥4—1219 (85.9%) |

| grade | G1—201 (8.5%) G2—1575 (67.1%) G3—571 (24.3) | G1—153 (10.8%) G2—988 (69.6%) G3—278 (19.6%) |

| events | OS (deaths)—317 (13.5%) PFS (relapses)—629 (26.8%) | OS (deaths)—130 (9.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meretukov, D.; Grechukhina, K.; Evdokimov, V.; Didych, D.; Kondratieva, S.; Rakitina, O.; Gordeev, A.; Shilo, P.; Khatkov, I.; Zhukova, L. Deriving Real-World Evidence from Non-English Electronic Medical Records in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Using Large Language Models. Cancers 2025, 17, 3836. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233836

Meretukov D, Grechukhina K, Evdokimov V, Didych D, Kondratieva S, Rakitina O, Gordeev A, Shilo P, Khatkov I, Zhukova L. Deriving Real-World Evidence from Non-English Electronic Medical Records in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Using Large Language Models. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3836. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233836

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeretukov, Daur, Katerina Grechukhina, Vladimir Evdokimov, Dmitry Didych, Sofia Kondratieva, Olga Rakitina, Alexander Gordeev, Polina Shilo, Igor Khatkov, and Lyudmila Zhukova. 2025. "Deriving Real-World Evidence from Non-English Electronic Medical Records in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Using Large Language Models" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3836. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233836

APA StyleMeretukov, D., Grechukhina, K., Evdokimov, V., Didych, D., Kondratieva, S., Rakitina, O., Gordeev, A., Shilo, P., Khatkov, I., & Zhukova, L. (2025). Deriving Real-World Evidence from Non-English Electronic Medical Records in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Using Large Language Models. Cancers, 17(23), 3836. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233836