Treating Pediatric Oncology Patients: The Emerging Role of Radioligand Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

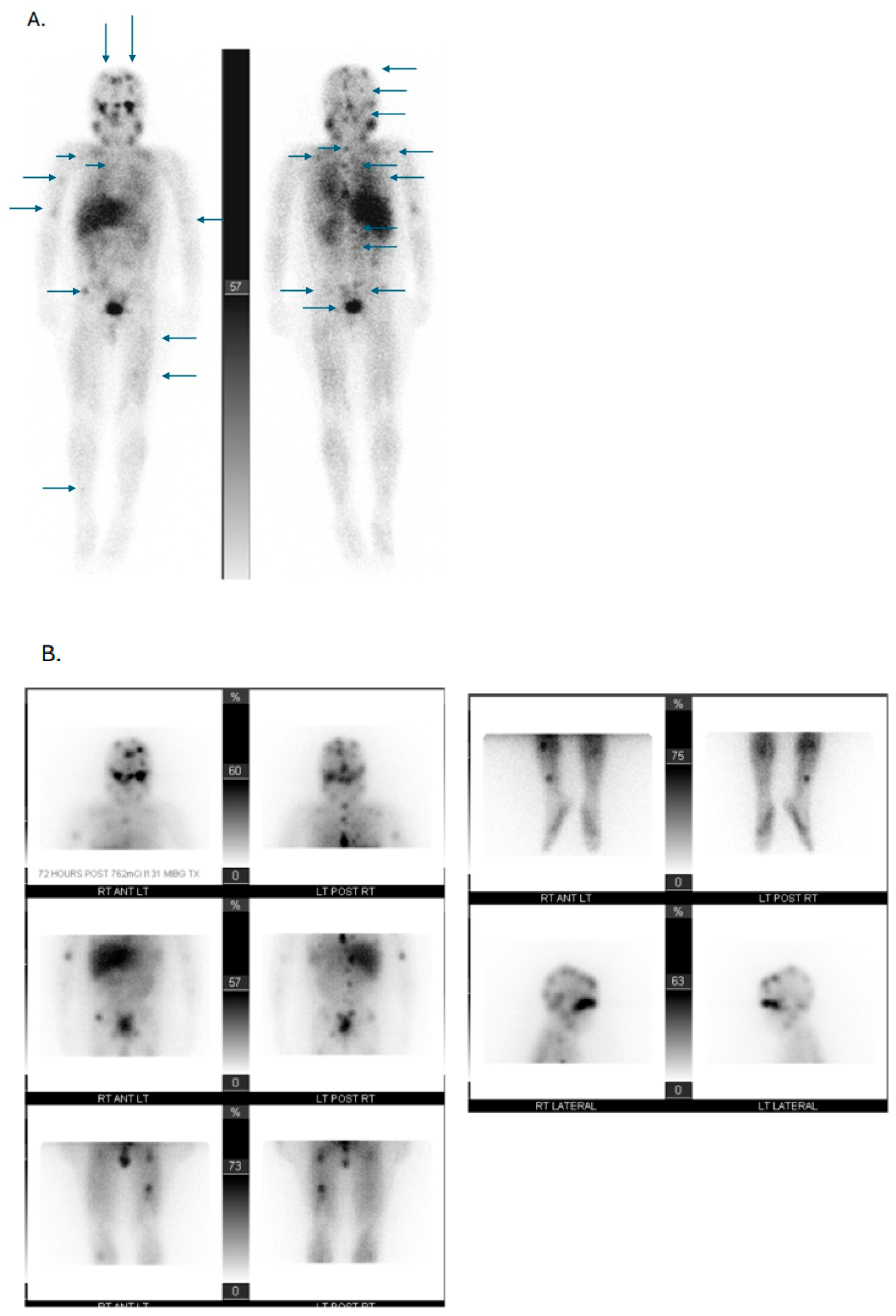

2. Current Use of Radionuclide Therapies in Pediatric Patients with Neuroblastoma or NETs

2.1. Radionuclide Therapies Overview

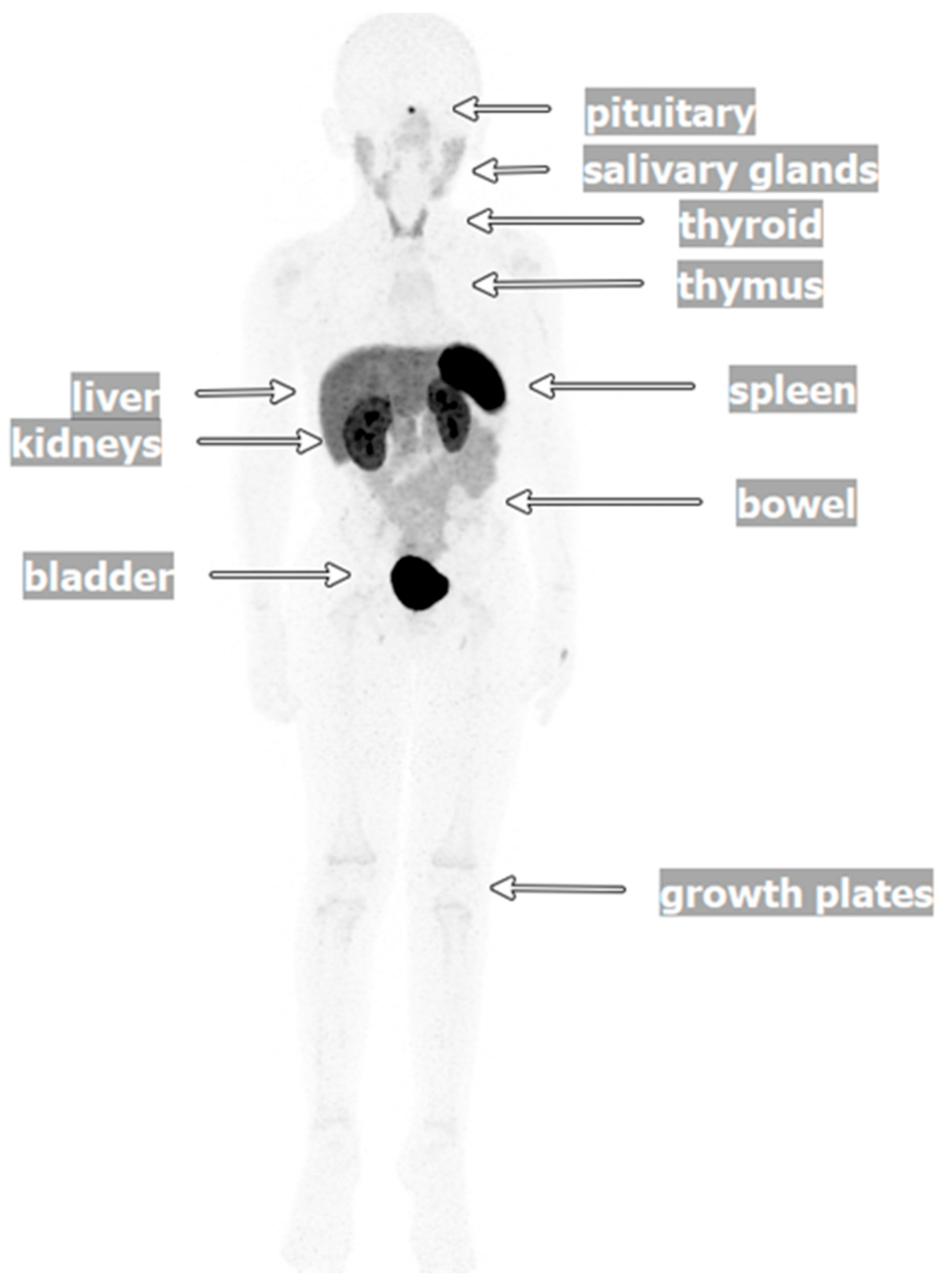

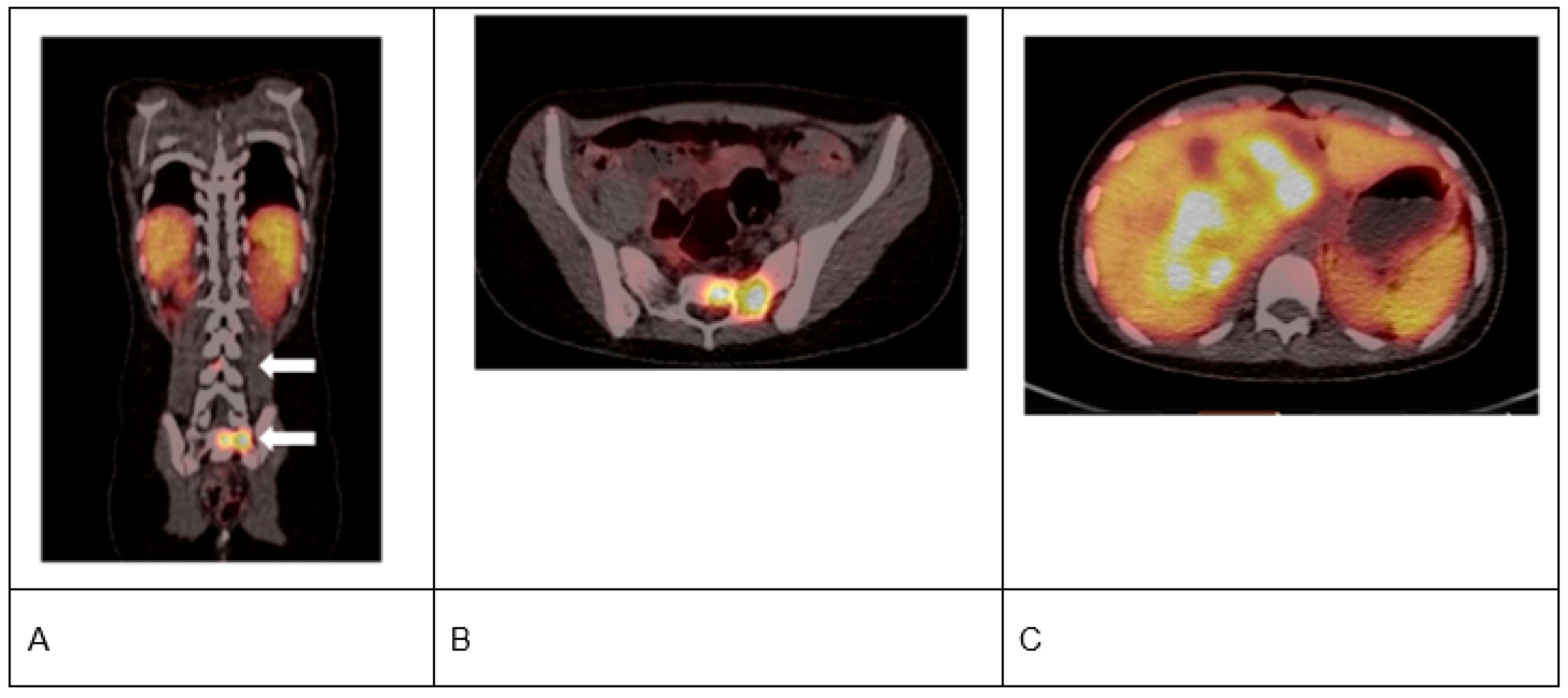

2.2. Radionuclides in Imaging and Theranostics

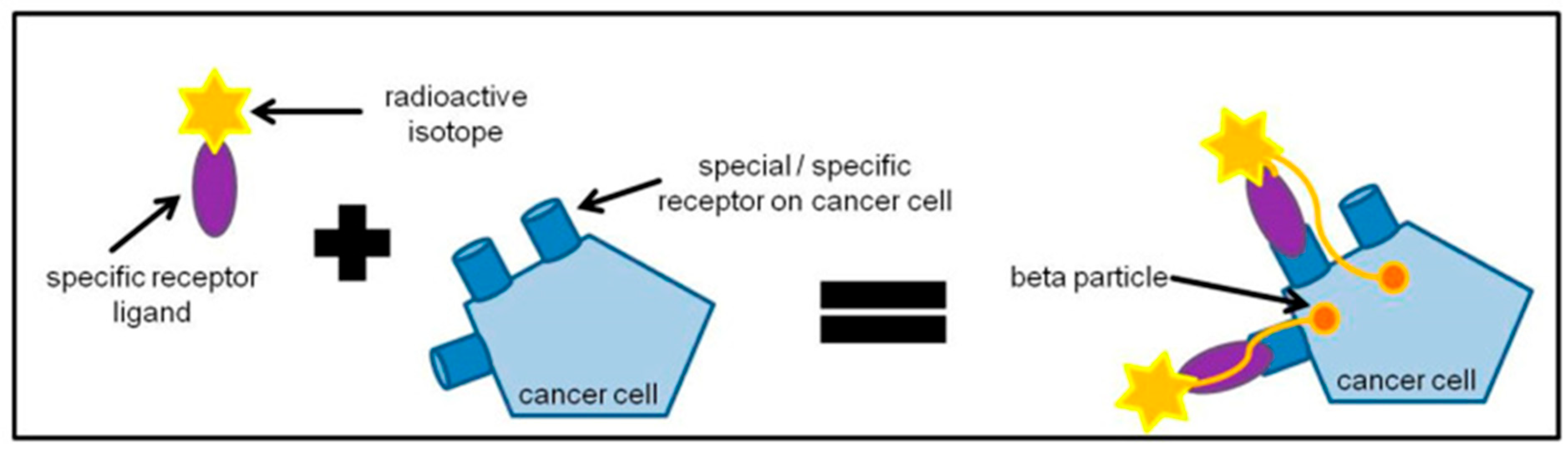

2.3. Mechanism of RLTs and Rationale for Their Use in Children

3. Efficacy of Current RLTs Used for Neuroblastoma and NETs in Pediatric Settings

4. Safety of Current RLTs Used for Neuroblastoma and NETs in Pediatric Settings

5. Future of RLT in Pediatric Settings

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NET | Neuroendocrine tumor |

| GEP-NET | Gastroenteropancreatic NET |

| PPGL | Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma |

| 68Ga-DOTATATE | 68Ga-labeled DOTA-D-Phe1-Tyr3-Thr8-octreotate |

| 177Lu-DOTATATE | [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE |

| 111In-DOTATATE | 111In-DOTA-octreotate |

| 123/131I-MIBG | 123/131I-meta iodobenzyl-guanine |

| SSTR | Somatostatin receptor |

| RLT | Radioligand therapy |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| 68Ga-DOTATOC | 68Ga-[tetraxetan-D-Phe1, Tyr3]-octreotide |

| 68Ga-DOTANOC | [68Ga-DOTA,1-Nal3]-octreotide |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| SPECT | Single-photon emission-CT |

| 18F-FDG PET/CT | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT |

| GD2 | Ganglioside GD2 |

| 90Y-DOTATOC | 90Y-DOTA0-Tyr3-octreotide |

| AE | Adverse event |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| IGF1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| SSA | Somatostatin analogs |

| GH | Growth hormone |

References

- Cives, M.; Strosberg, J.R. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhofer, G.; Peitzsch, M.; Bechmann, N.; Huebner, A. Biochemical diagnosis of catecholamine-producing tumors of childhood: Neuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 901760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniazek, B.; Cencelewicz, K.; Bzdziuch, P.; Mlynarczyk, L.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J.; Derwich, K. Neuroblastoma—A review of combination immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Qi, F.; Bian, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Ren, L.; Li, M.; Tang, W. Comparison of incidence and outcomes of neuroblastoma in children, adolescents, and adults in the United States: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program population study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e927218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, O.; Koycu, A.; Aydin, E. A rare tumor in the cervical sympathetic trunk: Ganglioneuroblastoma. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2016, 2016, 1454932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarski, A.; Maleika, P. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas: Is it also a challenge for pediatricians? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamporaki, C.; Casey, R.T. Current views on paediatric phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma with a focus on newest guidelines. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 39, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chintagumpala, M.; Hicks, J.; Nuchtern, J.G.; Okcu, M.F.; Venkatramani, R. Neuroendocrine tumor of the appendix in children. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 39, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Chan, K.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Bellizzi, A.M.; Rindi, G.; O’Toole, D.; Ge, P.S.; Jain, D.; Dasari, A.; Anaya, D.A.; et al. Critical updates in neuroendocrine tumors: Version 9 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnan, A.J.; Tocchio, S.; Kurtom, W.; Tadros, S.S. Pediatric neuroendocrine carcinoid tumors: Management, pathology, and imaging findings in a pediatric referral center. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.; Lodish, M. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2021, 33, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.J.M.; Nazari, M.A.; Jha, A.; Pacak, K. Pediatric metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: Clinical presentation and diagnosis, genetics, and therapeutic approaches. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 936178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gape, P.M.D.; Schultz, M.K.; Stasiuk, G.J.; Terry, S.Y.A. Towards effective targeted alpha therapy for neuroendocrine tumours: A review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; Bodei, L.; McDevitt, M.R.; Nedrow, J.R. Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: Clinical advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funeh, C.N.; Bridoux, J.; Ertveldt, T.; De Groof, T.W.M.; Chigoho, D.M.; Asiabi, P.; Covens, P.; D’Huyvetter, M.; Devoogdt, N. Optimizing the safety and efficacy of bio-radiopharmaceuticals for cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot, A.J.; Lam, M.; van Noesel, M.M. The current status and future potential of theranostics to diagnose and treat childhood cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 578286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhbahaei, S.; Sadaghiani, M.S.; Rowe, S.P.; Solnes, L.B. Neuroendocrine tumor theranostics: An update and emerging applications in clinical practice. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 217, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, K.M.; Binkovitz, L.A.; Trout, A.T.; Czachowski, M.R.; Seghers, V.J.; Lteif, A.N.; States, L.J. Pediatric applications of Dotatate: Early diagnostic and therapeutic experience. Pediatr. Radiol. 2020, 50, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, V.J.A.; Wenker, S.T.M.; Lam, M.; van Noesel, M.M.; Poot, A.J. Biologicals as theranostic vehicles in paediatric oncology. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2022, 114–115, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, G.P.; Beykan, S.; Bouterfa, H.; Kaufmann, J.; Bauman, A.; Lassmann, M.; Reubi, J.C.; Rivier, J.E.F.; Maecke, H.R.; Fani, M.; et al. Safety, biodistribution, and radiation dosimetry of 68Ga-OPS202 in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A prospective phase I imaging study. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA. FDA Approves Lutetium Lu 177 Dotatate for Pediatric Patients 12 Years and Older with GEP-NETS. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-lutetium-lu-177-dotatate-pediatric-patients-12-years-and-older-gep-nets (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Reubi, J.C.; Schonbrunn, A. Illuminating somatostatin analog action at neuroendocrine tumor receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, M.; Stalla, G.K. Somatostatin receptors: From signaling to clinical practice. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 34, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, J.M.; Hoeksema, M.D.; Staub, J.; Qian, J.; Harris, B.; Callison, J.C.; Miao, J.; Shi, C.; Eisenberg, R.; Chen, H.; et al. Somatostatin receptor 2 signaling promotes growth and tumor survival in small-cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, N.; Marrano, P.; Thorner, P.; Naranjo, A.; Van Ryn, C.; Martinez, D.; Batra, V.; Zhang, L.; Irwin, M.S.; Baruchel, S. Prevalence and clinical correlations of somatostatin receptor-2 (SSTR2) expression in neuroblastoma. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 41, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazow, M.A.; Fuller, C.; Trout, A.T.; Stanek, J.R.; Reuss, J.; Turpin, B.K.; Szabo, S.; Salloum, R. Immunohistochemical assessment and clinical, histopathologic, and molecular correlates of membranous somatostatin type-2A receptor expression in high-risk pediatric central nervous system tumors. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 996489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiviniemi, A.; Gardberg, M.; Kivinen, K.; Posti, J.P.; Vuorinen, V.; Sipila, J.; Rahi, M.; Sankinen, M.; Minn, H. Somatostatin receptor 2A in gliomas: Association with oligodendrogliomas and favourable outcome. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 49123–49132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtahedi, A.; Thamake, S.; Tworowska, I.; Ranganathan, D.; Delpassand, E.S. The value of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors compared to current FDA approved imaging modalities: A review of literature. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 4, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.H.; Hussein, Z.; Saad, F.F.; Shuaib, I.L. Diagnostic performance of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT, 18F-FDG PET/CT and 131I-MIBG scintigraphy in mapping metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 49, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, M.; Velikyan, I.; Garske-Roman, U.; Sorensen, J.; Eriksson, B.; Granberg, D.; Lundqvist, H.; Sundin, A.; Lubberink, M. Comparative biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 68Ga-DOTATOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyumcu, S.; Ozkan, Z.G.; Sanli, Y.; Yilmaz, E.; Mudun, A.; Adalet, I.; Unal, S. Physiological and tumoral uptake of 68Ga-DOTATATE: Standardized uptake values and challenges in interpretation. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2013, 27, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.C.; Smith, G.T.; Liu, E.; Moore, B.; Clanton, J.; Stabin, M. Measured human dosimetry of 68Ga-DOTATATE. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozguven, S.; Filizoglu, N.; Kesim, S.; Oksuzoglu, K.; Sen, F.; Ones, T.; Inanir, S.; Turoglu, H.T.; Erdil, T.Y. Physiological biodistribution of 68Ga-DOTA-TATE in normal subjects. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2021, 30, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebinga, H.; de Wit-van der Veen, B.J.; Beijnen, J.H.; Stokkel, M.P.M.; Dorlo, T.P.C.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Hendrikx, J. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to describe organ distribution of 68Ga-DOTATATE in patients without neuroendocrine tumors. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA. FDA Approves Lutetium Lu 177 Dotatate for Treatment of GEP-NETS. 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-lutetium-lu-177-dotatate-treatment-gep-nets (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Hennrich, U.; Kopka, K. Lutathera®: The first FDA- and EMA-approved radiopharmaceutical for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.A.; Sharp, S.E.; Bhatia, A.; Dietz, K.R.; McCarville, B.; Rajderkar, D.; Servaes, S.; Shulkin, B.L.; Singh, S.; Trout, A.T.; et al. Imaging of pediatric neuroblastoma: A COG Diagnostic Imaging Committee/SPR Oncology Committee White Paper. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70 (Suppl. S4), e29974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, S.E.; Trout, A.T.; Weiss, B.D.; Gelfand, M.J. MIBG in neuroblastoma diagnostic imaging and therapy. Radiographics 2016, 36, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, W.P.; Coppenrath, E.; Pfluger, T. Nuclear medicine and multimodality imaging of pediatric neuroblastoma. Pediatr. Radiol. 2013, 43, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

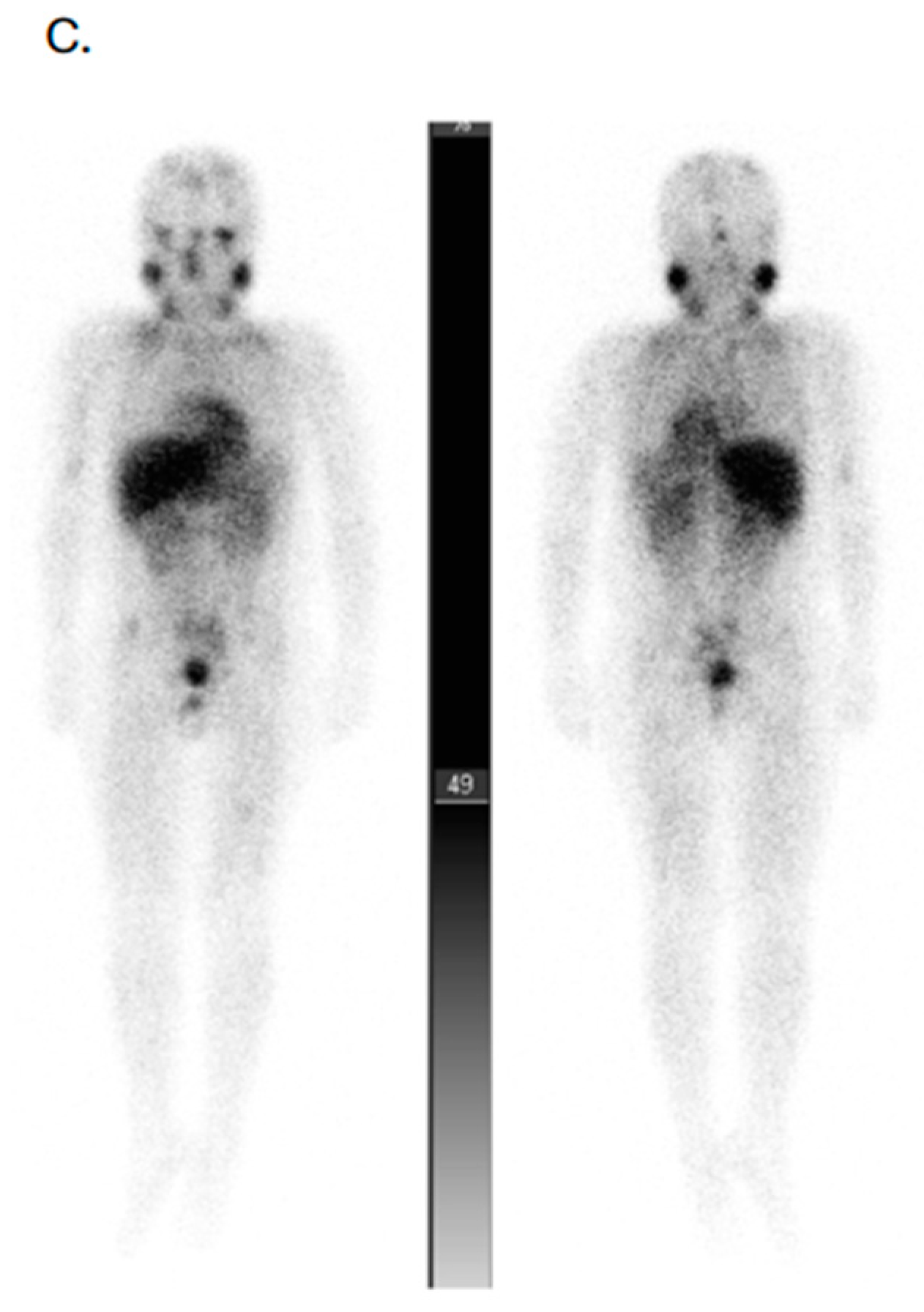

- Gains, J.E.; Aldridge, M.D.; Mattoli, M.V.; Bomanji, J.B.; Biassoni, L.; Shankar, A.; Gaze, M.N. 68Ga-DOTATATE and 123I-mIBG as imaging biomarkers of disease localisation in metastatic neuroblastoma: Implications for molecular radiotherapy. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2020, 41, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Poimenidou, M.; Craig, B.T. Current knowledge and perspectives of immunotherapies for neuroblastoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrenkov, K.; Ostrovnaya, I.; Gu, J.; Cheung, I.Y.; Cheung, N.K. Oncotargets GD2 and GD3 are highly expressed in sarcomas of children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH National Cancer Institute. FDA Approves First Therapy for High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2015/dinutuximab-neuroblastoma#:~:text=The%20Food%20and%20Drug%20Administration,risk%20form%20of%20this%20disease (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- EMA. Qarziba: EPAR—Product Information. 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/qarziba-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Furman, W.L.; McCarville, B.; Shulkin, B.L.; Davidoff, A.; Krasin, M.; Hsu, C.W.; Pan, H.; Wu, J.; Brennan, R.; Bishop, M.W.; et al. Improved outcome in children with newly diagnosed high-risk neuroblastoma treated with chemoimmunotherapy: Updated results of a phase II study using hu14.18K322A. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, M.H.; Veldhuijzen van Zanten, S.E.M.; van Vuurden, D.G.; Huisman, M.C.; Vugts, D.J.; Hoekstra, O.S.; van Dongen, G.A.; Kaspers, G.L. Molecular drug imaging: 89Zr-bevacizumab PET in children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, J.R.; Purvis, I.J.; Labak, C.M.; Guda, M.R.; Tsung, A.J.; Velpula, K.K.; Asuthkar, S. B7-H3 role in the immune landscape of cancer. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, K.; Pandit-Taskar, N.; Kushner, B.H.; Zanzonico, P.; Humm, J.L.; Tomlinson, U.; Donzelli, M.; Wolden, S.L.; Haque, S.; Dunkel, I.; et al. Phase 1 study of intraventricular 131I-omburtamab targeting B7H3 (CD276)-expressing CNS malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.E.; Howe, J.R. Imaging in neuroendocrine tumors: An update for the clinician. Int. J. Endocr. Oncol. 2015, 2, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Hofman, M.S.; Murray, W.K.; Wilson, S.; Wood, P.; Downie, P.; Super, L.; Hogg, A.; Eu, P.; Hicks, R.J. Initial experience with gallium-68 DOTA-octreotate PET/CT and peptide receptor radionuclide therapy for pediatric patients with refractory metastatic neuroblastoma. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 38, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xu, Q.; Yu, C. The efficacy and safety of Iodine-131-metaiodobenzylguanidine therapy in patients with neuroblastoma: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathpour, G.; Jafari, E.; Hashemi, A.; Dadgar, H.; Shahriari, M.; Zareifar, S.; Jenabzade, A.R.; Vali, R.; Ahmadzadehfar, H.; Assadi, M. Feasibility and therapeutic potential of combined peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with intensive chemotherapy for pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory metastatic neuroblastoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2021, 46, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundquist, F.; Georgantzi, K.; Jarvis, K.B.; Brok, J.; Koskenvuo, M.; Rascon, J.; van Noesel, M.; Gryback, P.; Nilsson, J.; Braat, A.; et al. A phase II trial of a personalized, dose-intense administration schedule of 177Lutetium-DOTATATE in children with primary refractory or relapsed high-risk neuroblastoma-LuDO-N. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 836230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT05278208: Lutathera forTreatment of Recurrent or Progressive High-Grade CNS Tumors. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05278208 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT03966651: A Clinical Study Evaluating the Safety of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT) with 177Lu-DOTA0-Tyr3-Octreotate in Children with Refractory or Recurrent Neuroblastoma Expressing Somatostatin Receptors. (NEUROBLU 02). Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03966651 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT06607692: Study in Children and Adolescents of 177Lu-DOTATATE (Lutathera®) Combined with the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib for the Treatment of Recurrent or Relapsed Solid Tumours Expressing Somatostatin Receptor (SSTR) (LuPARPed). (LUPARPED). Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06607692 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Gaze, M.N.; Handkiewicz-Junak, D.; Hladun, R.; Laetsch, T.W.; Sorge, C.; Sparks, R.; Wan, S.; Ceraulo, A.; Kluczewska-Galka, A.; Gámez-Cenzano, C.; et al. Safety and dosimetry of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE in adolescent patients with somatostatin receptor-positive gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, or pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: Primary analysis of the Phase II NETTER-P study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 4001–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT04559217: 68Ga-DOTATATE Neuroblastoma Imaging Pilot. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04559217 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Menda, Y.; O’Dorisio, M.S.; Kao, S.; Khanna, G.; Michael, S.; Connolly, M.; Babich, J.; O’Dorisio, T.; Bushnell, D.; Madsen, M. Phase I trial of 90Y-DOTATOC therapy in children and young adults with refractory solid tumors that express somatostatin receptors. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT04040088: An Investigational Scan (68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT) in Diagnosing Pediatric Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04040088 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02236910: An Open Label Registry Study of Lutetium-177 (DOTA0, TYR3) Octreotate (Lu-DOTA-TATE) Treatment in Patients with Somatostatin Receptor Positive Tumours. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02236910 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT03145857: A Study to Evaluate a New Way to Identify/Diagnose Tumours with Somatostatin Receptors Using [68]Ga-HA-DOTATATE and to Ensure It Is Safe to Use. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03145857 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Hamiditabar, M.; Ali, M.; Roys, J.; Wolin, E.M.; O’Dorisio, T.M.; Ranganathan, D.; Tworowska, I.; Strosberg, J.R.; Delpassand, E.S. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 177Lu-octreotate in patients with somatostatin receptor expressing neuroendocrine tumors: Six years’ assessment. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 42, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT01876771: A Trial to Assess the Safety and Effectiveness of Lutetium-177 Octreotate Therapy in Neuroendocrine Tumours. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01876771 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Strosberg, J.R.; Caplin, M.E.; Kunz, P.L.; Ruszniewski, P.B.; Bodei, L.; Hendifar, A.; Mittra, E.; Wolin, E.M.; Yao, J.C.; Pavel, M.E.; et al. 177Lu-Dotatate plus long-acting octreotide versus high-dose long-acting octreotide in patients with midgut neuroendocrine tumours (NETTER-1): Final overall survival and long-term safety results from an open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosberg, J.; El-Haddad, G.; Wolin, E.; Hendifar, A.; Yao, J.; Chasen, B.; Mittra, E.; Kunz, P.L.; Kulke, M.H.; Jacene, H.; et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabander, T.; van der Zwan, W.A.; Teunissen, J.J.M.; Kam, B.L.R.; Feelders, R.A.; de Herder, W.W.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; Franssen, G.J.H.; Krenning, E.P.; Kwekkeboom, D.J. Long-term efficacy, survival, and safety of [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate in patients with gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4617–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundlöv, A.; Sjögreen-Gleisner, K.; Tennvall, J.; Dahl, L.; Svensson, J.; Åkesson, A.; Bernhardt, P.; Lindgren, O. Pituitary function after high-dose 177Lu-DOTATATE therapy and long-term follow-up. Neuroendocrinology. 2021, 111, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menda, Y.; Madsen, M.T.; O’Dorisio, T.M.; Sunderland, J.J.; Watkins, G.L.; Dillon, J.S.; Mott, S.L.; Schultz, M.K.; Zamba, G.K.D.; Bushnell, D.L.; et al. 90Y-DOTATOC dosimetry-based personalized peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 1692–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Gao, H.; Luo, C.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Q.; Shi, J.; Wang, F. Palmitic acid-conjugated radiopharmaceutical for integrin αvβ3-targeted radionuclide therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2022, 14, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prive, B.M.; Boussihmad, M.A.; Timmermans, B.; van Gemert, W.A.; Peters, S.M.B.; Derks, Y.H.W.; van Lith, S.A.M.; Mehra, N.; Nagarajah, J.; Heskamp, S.; et al. Fibroblast activation protein-targeted radionuclide therapy: Background, opportunities, and challenges of first (pre)clinical studies. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 1906–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddio, A.; Pietroluongo, E.; Lamia, M.R.; Luciano, A.; Caltavituro, A.; Buonaiuto, R.; Pecoraro, G.; De Placido, P.; Palmieri, G.; Bianco, R.; et al. DLL3 as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target in neuroendocrine neoplasms: A narrative review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 204, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutfilen, B.; Souza, S.A.; Valentini, G. Copper-64: A real theranostic agent. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018, 12, 3235–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dearling, J.L.J.; van Dam, E.M.; Harris, M.J.; Packard, A.B. Detection and therapy of neuroblastoma minimal residual disease using [64/67Cu]Cu-SARTATE in a preclinical model of hepatic metastases. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, C.; Jeffery, C.M.; Roselt, P.D.; van Dam, E.M.; Jackson, S.; Kuan, K.; Jackson, P.; Binns, D.; van Zuylekom, J.; Harris, M.J.; et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 67Cu-CuSarTATE is highly efficacious against a somatostatin-positive neuroendocrine tumor model. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Kunos, C.; Arnold, S.M.; Weiss, H.; Ivy, S.P.; Gore, S.; Rubinstein, L.; Pelosof, L.; Beumer, J.H.; Kolesar, J.; et al. A phase II randomized control trial of triapine plus lutetium 177 DOTATATE versus lutetium 177 DOTATATE alone for well-differentiated somatostatin receptor-positive neuroendocrine tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, TPS4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Witt, R.; Nesper-Brock, M.; Milde, T.; Hettmer, S.; Fruhwald, M.C.; Rossig, C.; Fischer, M.; Reinhardt, D.; Taylor, L.A.; et al. A study of regulatory challenges of pediatric oncology Phase I/II trial submissions and guidance on protocol development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neel, D.V.; Shulman, D.S.; DuBois, S.G. Timing of first-in-child trials of FDA-approved oncology drugs. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 112, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaudommongkon, I.; John Miyagi, S.; Green, D.J.; Burnham, J.M.; van den Anker, J.N.; Park, K.; Wu, J.; McCune, S.K.; Yao, L.; Burckart, G.J. Combined pediatric and adult trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration 2012–2018. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaguelidou, F.; Ouedraogo, M.; Treluyer, J.M.; Le Jeunne, C.; Annereau, M.; Blanc, P.; Bureau, S.; Ducassou, S.; Fiquet, B.; Flamein, F.; et al. Paediatric drug development and evaluation: Existing challenges and recommendations. Therapies 2023, 78, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutanzi, K.R.; Lumen, A.; Koturbash, I.; Miousse, I.R. Pediatric exposures to ionizing radiation: Carcinogenic considerations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Design | Patient Population | N | Endpoints | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies in pediatric populations only | |||||

| Retrospective [52] | 177Lu-DOTATATE combined with chemotherapy | Pediatric patients (age: 4–9 years) with SSTR-positive relapsed/refractory metastatic neuroblastoma | 14 |

| Efficacy:

|

| Phase 2, open-label, multicenter, single-arm trial (LuDO-N; NCT04903899) [53] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory high-risk neuroblastoma | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 1/2, open-label trial (NCT05278208) [54] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Pediatric patients with progressive/recurrent high-grade CNS tumors and meningiomas | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 1, open-label trial (NEUROBLU 02; NCT03966651) [55] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Pediatric patients with SSTR-positive refractory/recurrent neuroblastoma | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 2, open-label trial (LUPARPED; NCT06607692) [56] | 177Lu-DOTATATE combined with olaparib | Pediatric patients with SSTR-positive recurrent/relapsed solid tumors | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 2, NETTER-P trial (NCT04711135) [57] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Pediatric patients, aged 13–17 years with SSTR-positive GEP-NETs or PPGL | 11 |

| Dosimetry:

|

| Studies in populations of young adult or pediatric patients | |||||

| Phase 2, open-label, diagnostic study (NCT04559217) [58] | 68Ga-DOTATATE and 123I-MIBG | Patients (≤21 years) with neuroblastoma | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 1 (NCT00049023) [59] | 90Y-DOTATOC and co-administration of amino acid | Pediatric and young adult patients (2–25 years old) with refractory SSTR-positive solid tumors | 17 |

| Efficacy:

|

| Phase 1, open-label, diagnostic study (NCT04040088) [60] | 68Ga-DOTATATE | Pediatric and young adult patients (<30 years old) with NETs | Active, not recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Studies of adult patients including some pediatric patients | |||||

| Phase 2, open-label trial (NCT02236910) [61] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Patients, including pediatric patients (≥14 years), with SSTR-positive solid tumors | Active, not recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 1/2, open-label, diagnostic study (NCT03145857) [62] | 68Ga-DOTATATE | Patients, including pediatric patients (≥14 years old), with SSTR-positive tumors | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

| Phase 2 (NCT01237457) [63] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Patients, aged 11–87 years with inoperable, well-to-moderately differentiated, metastatic NETs | 144 |

| Efficacy:

|

| Phase 2, open-label, single-site trial (NCT01876771) [64] | 177Lu-DOTATATE | Patients, aged 14–90 years with SSTR-positive NETs | Recruiting |

| Not published yet |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laetsch, T.W.; States, L.J.; Lazow, M.A.; Chauhan, A. Treating Pediatric Oncology Patients: The Emerging Role of Radioligand Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233821

Laetsch TW, States LJ, Lazow MA, Chauhan A. Treating Pediatric Oncology Patients: The Emerging Role of Radioligand Therapy. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233821

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaetsch, Theodore W., Lisa J. States, Margot A. Lazow, and Aman Chauhan. 2025. "Treating Pediatric Oncology Patients: The Emerging Role of Radioligand Therapy" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233821

APA StyleLaetsch, T. W., States, L. J., Lazow, M. A., & Chauhan, A. (2025). Treating Pediatric Oncology Patients: The Emerging Role of Radioligand Therapy. Cancers, 17(23), 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233821