Histotripsy Dose Impacts Treated Tumor Immune Infiltration and Survival Outcomes in a Murine B16F10 Melanoma Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice, Cell Line, Inoculation, and Measurement

2.2. Ultrasound-Guided Histotripsy Therapy

2.3. Tumor Processing for Microscopy

2.4. Histological Damage Scoring

2.5. Immunohistochemistry Staining and Imaging

2.6. Survival Studies

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

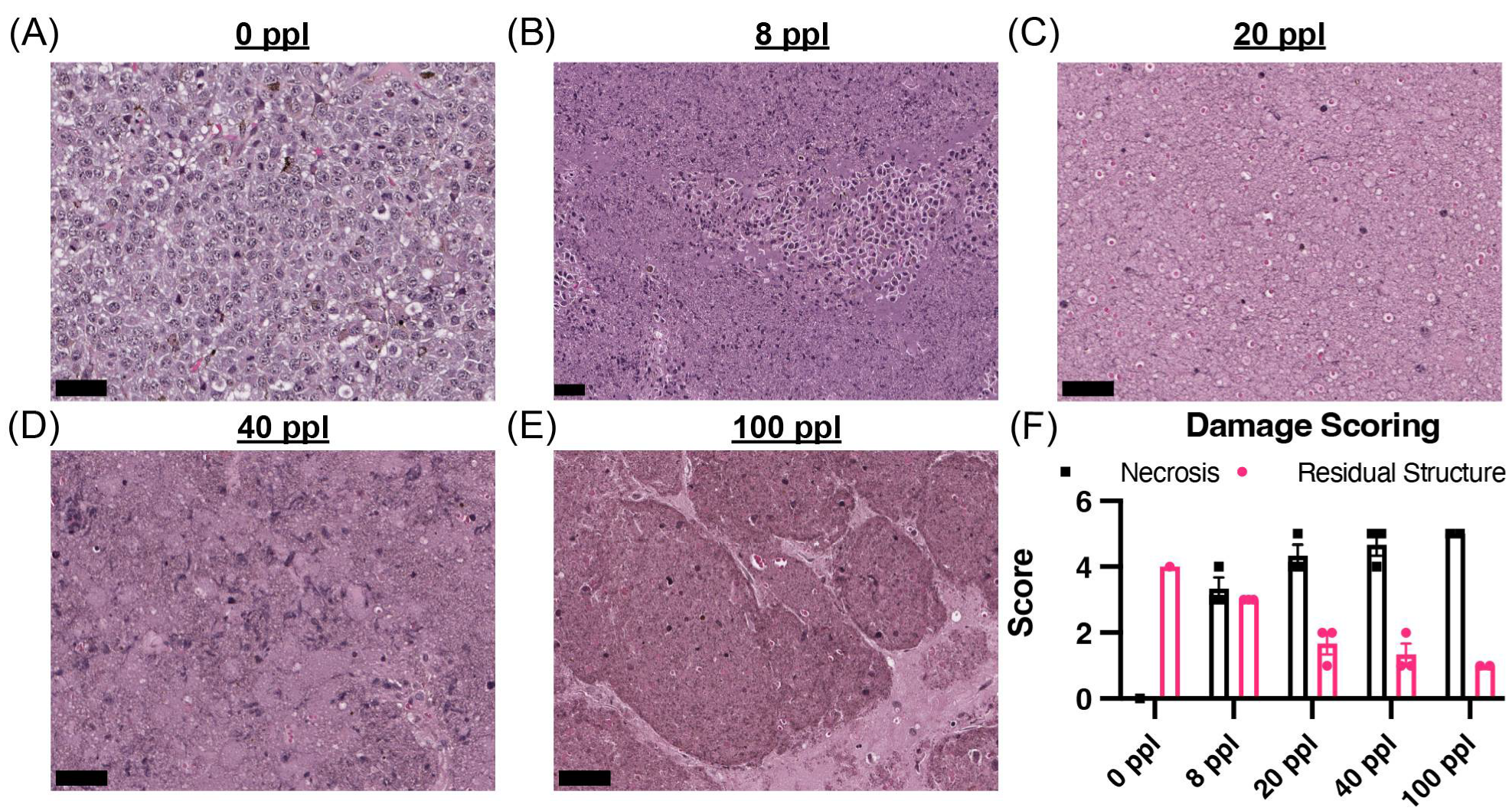

3.1. Tested Histotripsy Doses Induced Considerable Tumor Disruption

3.2. Histotripsy Monotherapy Provides Dose-Dependent Survival Benefits

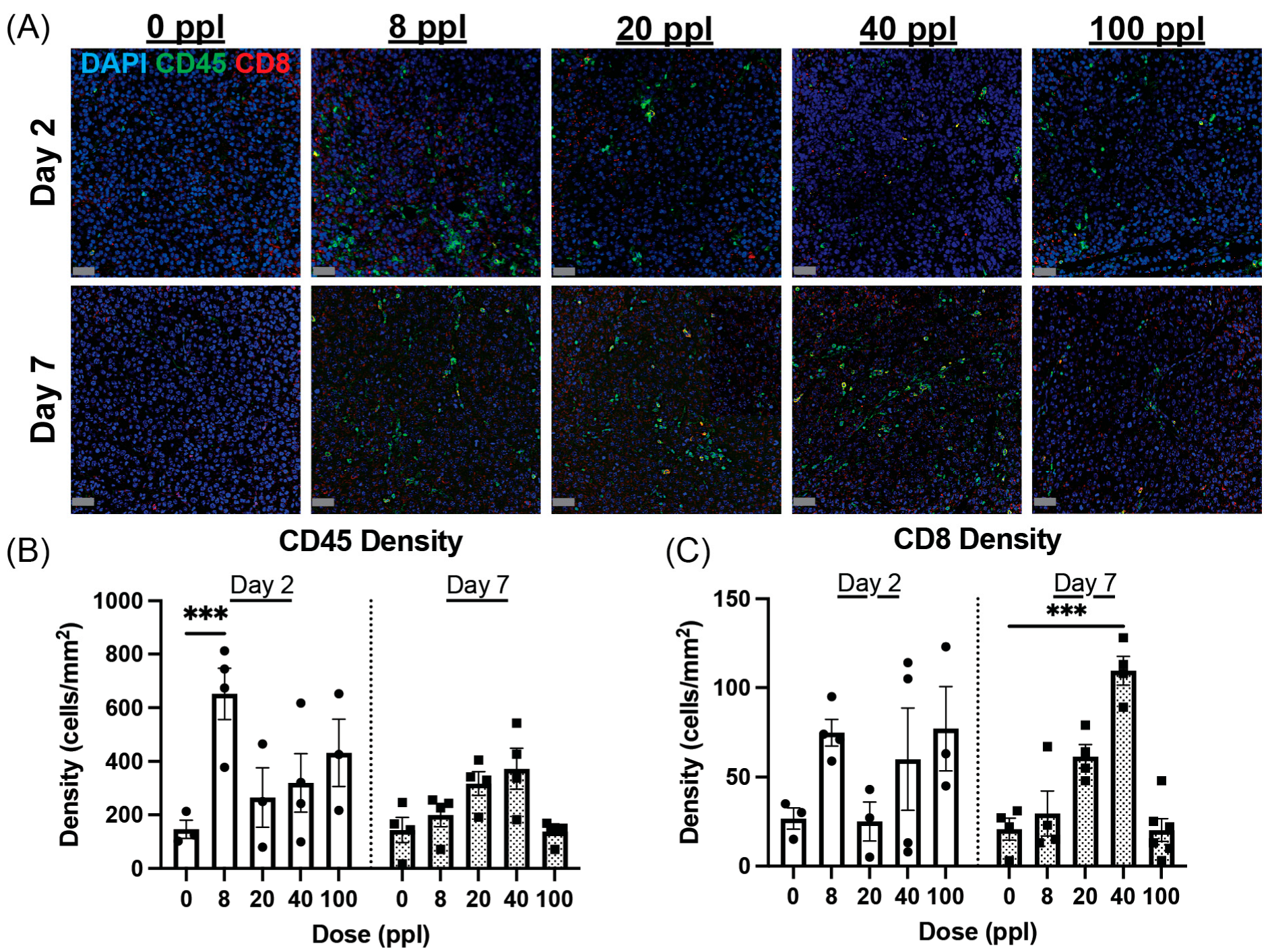

3.3. Dose-Dependent Change in Intra-Tumor Immune Cell Profile After Histotripsy

3.4. General Immune Cell Infiltration Peaks at Intermediate Dose

3.5. CD8+ T-Cell Infiltration Also Peaks at Intermediate Dose

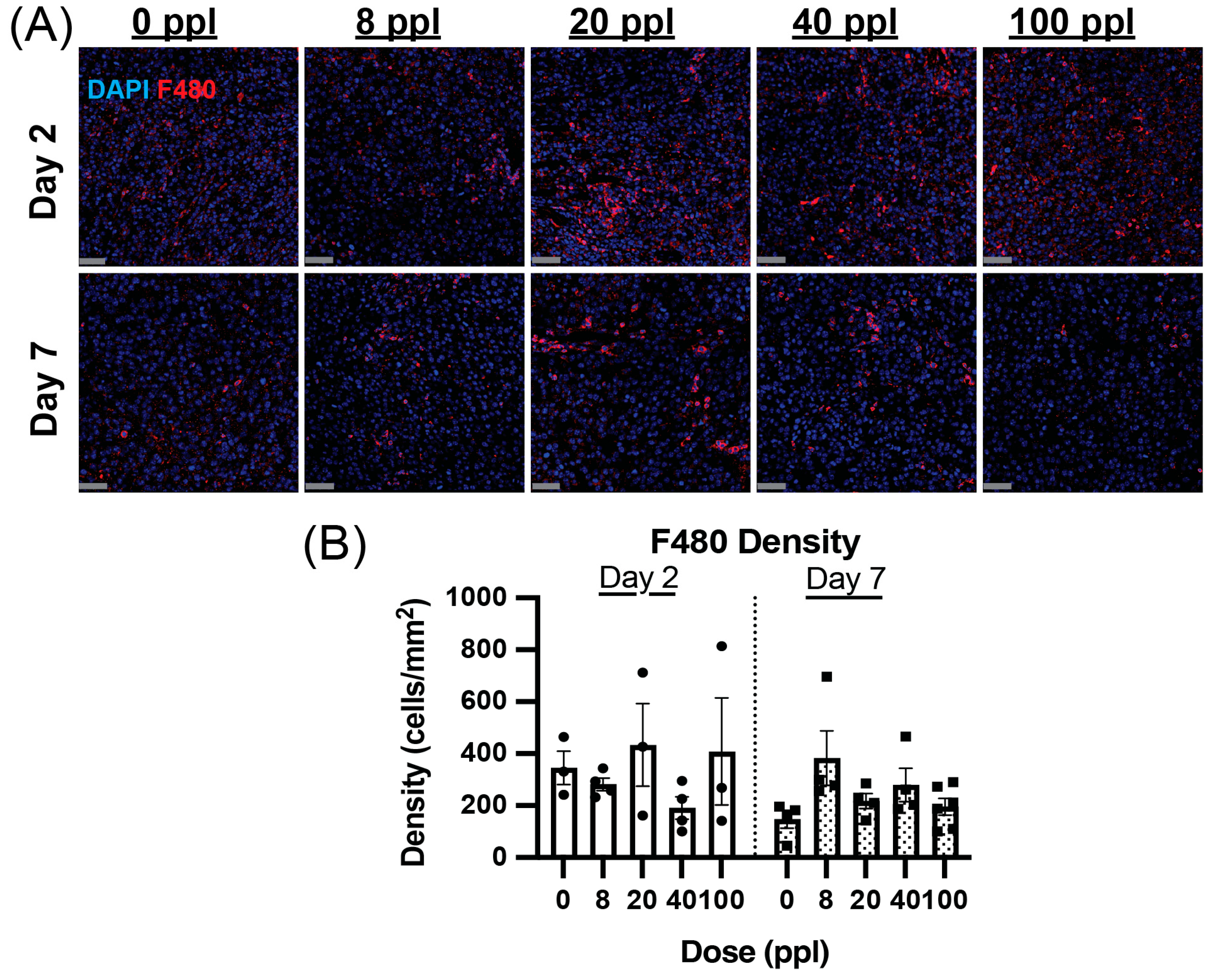

3.6. Dose-Dependent Decrease in F480+ Macrophage Prevalence Is Temporary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Wiggermann, P.; Pech, M.; Serres-Créixams, X.; White, S.B.; Davis, C.; Ahmed, O.; Parikh, N.D.; Planert, M.; Thormann, M.; et al. The #HOPE4LIVER Single-Arm Pivotal Trial for Histotripsy of Primary and Metastatic Liver Tumors. Radiology 2024, 312, e233051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, T.M.; Pech, M.; Thormann, M.; Serres, X.; Littler, P.; Stenberg, B.; Lenton, J.; Smith, J.; Wiggermann, P.; Planert, M.; et al. A Multi-Centre, Single Arm, Non-Randomized, Prospective European Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of the HistoSonics System in the Treatment of Primary and Metastatic Liver Cancers (#HOPE4LIVER). Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 46, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaisavljevich, E.; Maxwell, A.; Mancia, L.; Johnsen, E.; Cain, C.; Xu, Z. Visualizing the Histotripsy Process: Bubble Cloud–Cancer Cell Interactions in a Tissue-Mimicking Environment. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 2466–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khokhlova, V.A.; Fowlkes, J.B.; Roberts, W.W.; Schade, G.R.; Xu, Z.; Khokhlova, T.D.; Hall, T.L.; Maxwell, A.D.; Wang, Y.-N.; Cain, C.A. Histotripsy Methods in Mechanical Disintegration of Tissue: Towards Clinical Applications. Int. J. Hyperth. 2015, 31, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worlikar, T.; Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Vlaisavljevich, E.; Hubbard, R.; Shi, J.; Hall, T.L.; Cho, C.S.; Lee, F.T.; Greve, J.; Xu, Z. Effects of Histotripsy on Local Tumor Progression in an in Vivo Orthotopic Rodent Liver Tumor Model. BME Front. 2020, 2020, 9830304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabrinsky, E.; Macklis, J.; Bitran, J. A Review of the Abscopal Effect in the Era of Immunotherapy. Cureus 2022, 14, e29620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mole, R.H. Whole Body Irradiation—Radiobiology or Medicine? Br. J. Radiol. 1953, 26, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Green, M.; Choi, J.E.; Gijón, M.; Kennedy, P.D.; Johnson, J.K.; Liao, P.; Lang, X.; Kryczek, I.; Sell, A.; et al. CD8+ T Cells Regulate Tumour Ferroptosis during Cancer Immunotherapy. Nature 2019, 569, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Ferroptosis, Necroptosis, and Pyroptosis in Anticancer Immunity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Worlikar, T.; Felsted, A.E.; Ganguly, A.; Beems, M.V.; Hubbard, R.; Pepple, A.L.; Kevelin, A.A.; Garavaglia, H.; Dib, J.; et al. Non-Thermal Histotripsy Tumor Ablation Promotes Abscopal Immune Responses That Enhance Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepple, A.L.; Guy, J.L.; McGinnis, R.; Felsted, A.E.; Song, B.; Hubbard, R.; Worlikar, T.; Garavaglia, H.; Dib, J.; Chao, H.; et al. Spatiotemporal Local and Abscopal Cell Death and Immune Responses to Histotripsy Focused Ultrasound Tumor Ablation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1012799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Jové, J.; Serres-Créixams, X.; Ziemlewicz, T.J.; Cannata, J.M. Liver Histotripsy Mediated Abscopal Effect—Case Report. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 3001–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Owens, G.; Gordon, D.; Cain, C.; Ludomirsky, A. Noninvasive Creation of an Atrial Septal Defect by Histotripsy in a Canine Model. Circulation 2010, 121, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Raghavan, M.; Hall, T.L.; Chang, C.; Mycek, M.-A.; Fowlkes, J.B.; Cain, C.A. High Speed Imaging of Bubble Clouds Generated in Pulsed Ultrasound Cavitational Therapy—Histotripsy. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2007, 54, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Burns, K.; Ong, E.; Couillard, A.; Parikh, N.D.; Caoili, E.; Kim, J.; Aucejo, F.; Schlegel, A.; Knott, E.; et al. The First International Experience with Histotripsy: A Safety Analysis of 230 Cases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, K.B.; Vlaisavljevich, E.; Maxwell, A.D. For Whom the Bubble Grows: Physical Principles of Bubble Nucleation and Dynamics in Histotripsy Ultrasound Therapy. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 1056–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; McGinnis, R.; Cao, Z.; Baker, J.R.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S. Ultrasound-Guided Histotripsy Triggers the Release of Tumor-Associated Antigens from Breast Cancers. Cancers 2025, 17, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, S.C.; Yeats, E.; Shi, J.; Hall, T.; Fowlkes, J.B.; Xu, Z.; Sukovich, J.R. Acoustic Cavitation Emissions Predict Near-Complete/Complete Histotripsy Treatment in Soft Tissues. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2025, 51, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomayko, M.M.; Reynolds, C.P. Determination of Subcutaneous Tumor Size in Athymic (Nude) Mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1989, 24, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euhus, D.M.; Hudd, C.; Laregina, M.C.; Johnson, F.E. Tumor Measurement in the Nude Mouse. J. Surg. Oncol. 1986, 31, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Kosinski, M.; Biecek, P.; Fabian, S. Survminer: Drawing Survival Curves Using “Ggplot2”. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/survminer.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Forrest, W.F.; Alicke, B.; Mayba, O.; Osinska, M.; Jakubczak, M.; Piatkowski, P.; Choniawko, L.; Starr, A.; Gould, S.E. Generalized Additive Mixed Modeling of Longitudinal Tumor Growth Reduces Bias and Improves Decision Making in Translational Oncology. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 5089–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-37027-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, J.W. Tumour-Educated Macrophages Promote Tumour Progression and Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Neoplastic Progression: A Paradigm for the in Vivo Function of Chemokines. Lab. Investig. 1994, 71, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Modak, M.; Mattes, A.-K.; Reiss, D.; Skronska-Wasek, W.; Langlois, R.; Sabarth, N.; Konopitzky, R.; Ramirez, F.; Lehr, K.; Mayr, T.; et al. CD206+ Tumor-Associated Macrophages Cross-Present Tumor Antigen and Drive Antitumor Immunity. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e155022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Kambayashi, Y.; Fujisawa, Y.; Hidaka, T.; Aiba, S. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: Therapeutic Targets for Skin Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; To, K.K.W.; Zhu, S.; Wang, F.; Fu, L. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Remodel the Suppressive Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Targeted Therapy for Immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozat, K.; Tamoutounour, S.; Vu Manh, T.-P.; Fossum, E.; Luche, H.; Ardouin, L.; Guilliams, M.; Azukizawa, H.; Bogen, B.; Malissen, B.; et al. Cutting Edge: Expression of XCR1 Defines Mouse Lymphoid-Tissue Resident and Migratory Dendritic Cells of the CD8α+ Type. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 4411–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Saffold, S.; Cao, X.; Krauss, J.; Chen, W. Eliciting T Cell Immunity Against Poorly Immunogenic Tumors by Immunization with Dendritic Cell-Tumor Fusion Vaccines1. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 5516–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wan, Y.; Cai, H.; Deng, L.; Li, R. The Immunogenicity and Anti-Tumor Efficacy of a Rationally Designed Neoantigen Vaccine for B16F10 Mouse Melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgers, J.S.W.; Lenkala, D.; Kohler, V.; Jackson, E.K.; Linssen, M.D.; Hymson, S.; McCarthy, B.; O’Reilly Cosgrove, E.; Balogh, K.N.; Esaulova, E.; et al. Personalized, Autologous Neoantigen-Specific T Cell Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma: A Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thim, E.A.; Kitelinger, L.E.; Rivera-Escalera, F.; Mathew, A.S.; Elliott, M.R.; Bullock, T.N.J.; Price, R.J. Focused Ultrasound Ablation of Melanoma with Boiling Histotripsy Yields Abscopal Tumor Control and Antigen-Dependent Dendritic Cell Activation. Theranostics 2024, 14, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.G.; Karimi, S.S.; Barry-Holson, K.; Angell, T.E.; Murphy, K.A.; Church, C.H.; Ohlfest, J.R.; Hu, P.; Epstein, A.L. Immunogenicity of Murine Solid Tumor Models as a Defining Feature of In Vivo Behavior and Response to Immunotherapy. J. Immunother. 2013, 36, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersey, T.W.; Van Eyk, J.; Lannin, D.R.; Chua, A.N.; Tafra, L. Comparison of Intradermal and Subcutaneous Injections in Lymphatic Mapping. J. Surg. Res. 2001, 96, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Esser, S.; van den Bosch, M.A.A.J.; van Diest, P.J.; Mali, W.T.M.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.M.; van Hillegersberg, R. Minimally Invasive Ablative Therapies for Invasive Breast Carcinomas: An Overview of Current Literature. World J. Surg. 2007, 31, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Queen, H.; Ferris, S.F.; McGinnis, R.; Karanam, C.; Gatteno, N.; Buglak, K.; Kim, H.; Xu, J.; Goughenour, K.D.; et al. Histotripsy-Focused Ultrasound Treatment Abrogates Tumor Hypoxia Responses and Stimulates Antitumor Immune Responses in Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.; Lin, E.J.; Tartar, D. Immunology of Wound Healing. Curr. Derm. Rep. 2018, 7, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, J.N. Ki67 Is a Promising Molecular Target in the Diagnosis of Cancer (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, C.; Gajewski, T.F.; Mackensen, A. Interaction of PD-L1 on Tumor Cells with PD-1 on Tumor-Specific T Cells as a Mechanism of Immune Evasion: Implications for Tumor Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2005, 54, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.J., Jr.; Mulé, J.J.; Spiess, P.J.; Rosenberg, S.A. Interferon Gamma and Tumor Necrosis Factor Have a Role in Tumor Regressions Mediated by Murine CD8+ Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 173, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, S.J.; Rajotte, R.V.; Korbutt, G.S.; Bleackley, R.C. Granzyme B: A Natural Born Killer. Immunol. Rev. 2003, 193, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scoring Metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Necrosis | Score | Residual Structure | Score |

| 0% | 0 | None present | 0 |

| 1–25% | 1 | Patchy small areas | 1 |

| 26–50% | 2 | Larger patchy areas | 2 |

| 51–75% | 3 | Diffuse areas | 3 |

| 76–95% | 4 | Intact | 4 |

| >95% | 5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGinnis, R.; Song, B.; Kim, H.; Lorenzon, A.; Shi, J.; Zhao, L.; Cho, C.S.; Ganguly, A.; Xu, Z. Histotripsy Dose Impacts Treated Tumor Immune Infiltration and Survival Outcomes in a Murine B16F10 Melanoma Model. Cancers 2025, 17, 3773. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233773

McGinnis R, Song B, Kim H, Lorenzon A, Shi J, Zhao L, Cho CS, Ganguly A, Xu Z. Histotripsy Dose Impacts Treated Tumor Immune Infiltration and Survival Outcomes in a Murine B16F10 Melanoma Model. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3773. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233773

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGinnis, Reliza, Brian Song, Hanna Kim, Anna Lorenzon, Jiaqi Shi, Lili Zhao, Clifford S. Cho, Anutosh Ganguly, and Zhen Xu. 2025. "Histotripsy Dose Impacts Treated Tumor Immune Infiltration and Survival Outcomes in a Murine B16F10 Melanoma Model" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3773. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233773

APA StyleMcGinnis, R., Song, B., Kim, H., Lorenzon, A., Shi, J., Zhao, L., Cho, C. S., Ganguly, A., & Xu, Z. (2025). Histotripsy Dose Impacts Treated Tumor Immune Infiltration and Survival Outcomes in a Murine B16F10 Melanoma Model. Cancers, 17(23), 3773. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233773