Improving Advanced Communication Skills Towards the Family System: A Scoping Review of Family Meeting Training in Oncology and Other Healthcare Settings

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Background

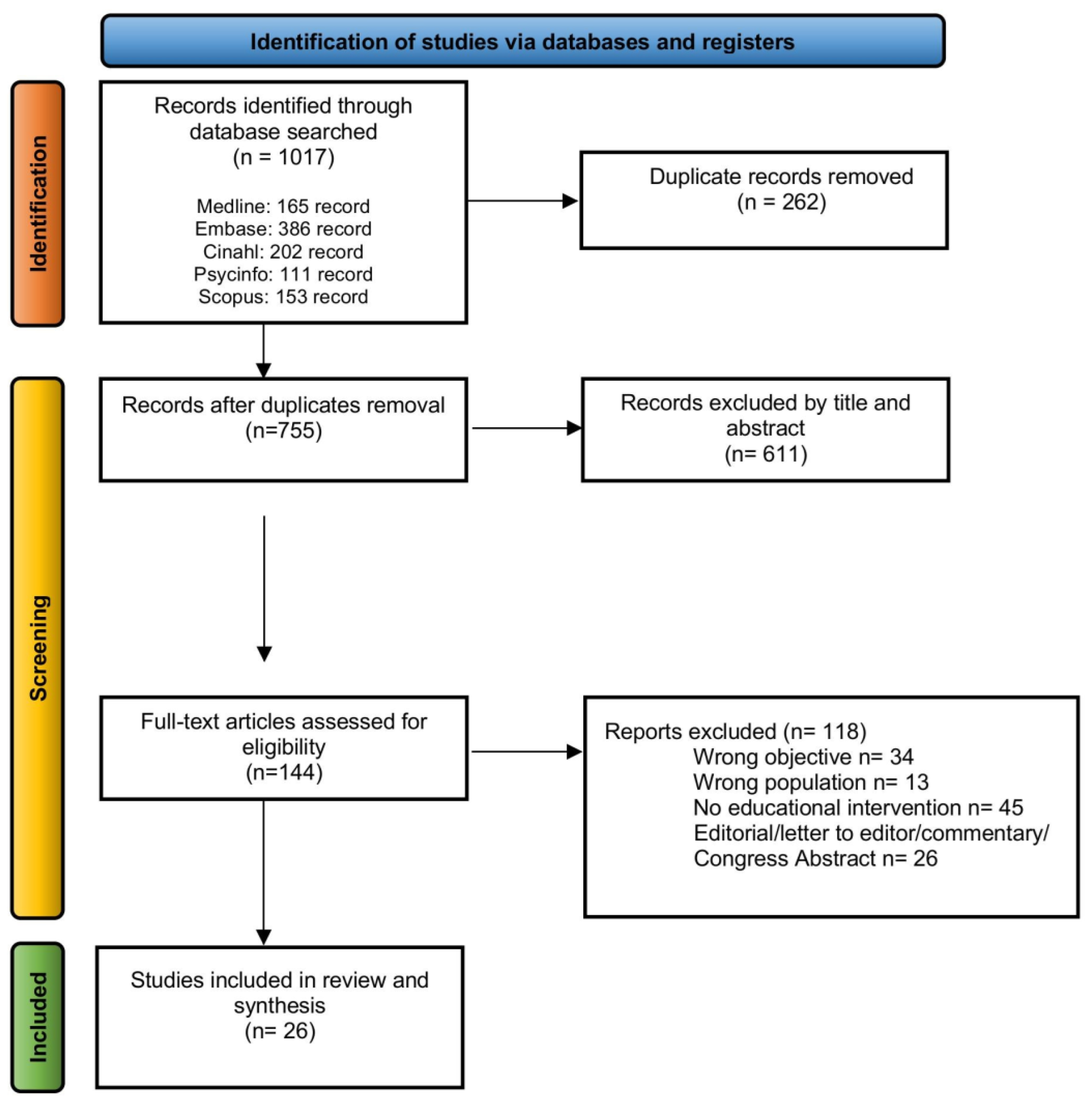

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Screening and Selection of Studies

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

2.7. Synthesis of the Results

3. Results

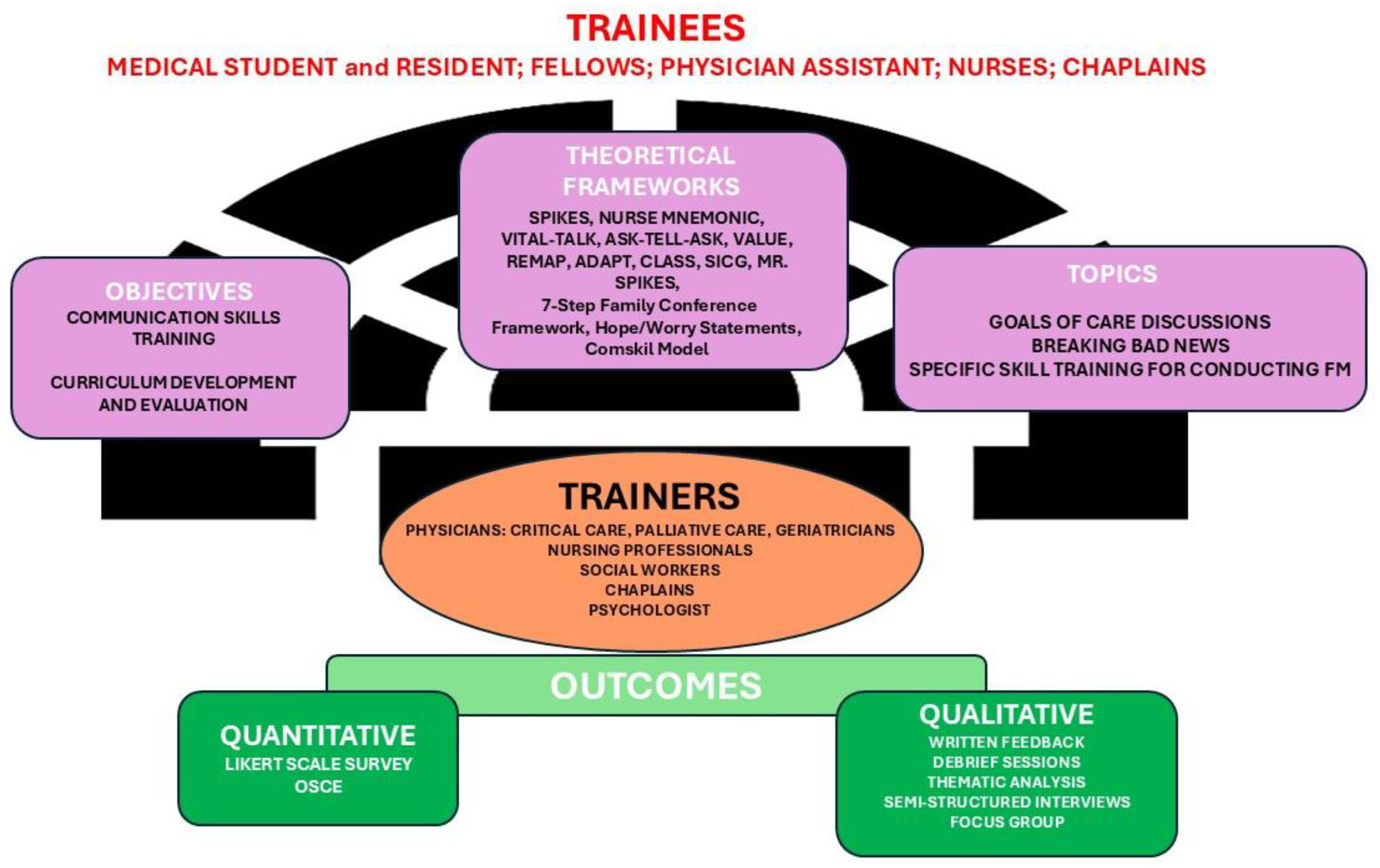

3.1. Study Objective

- (i)

- (ii)

3.2. Trainers

3.3. Trainees

3.4. Setting of Training

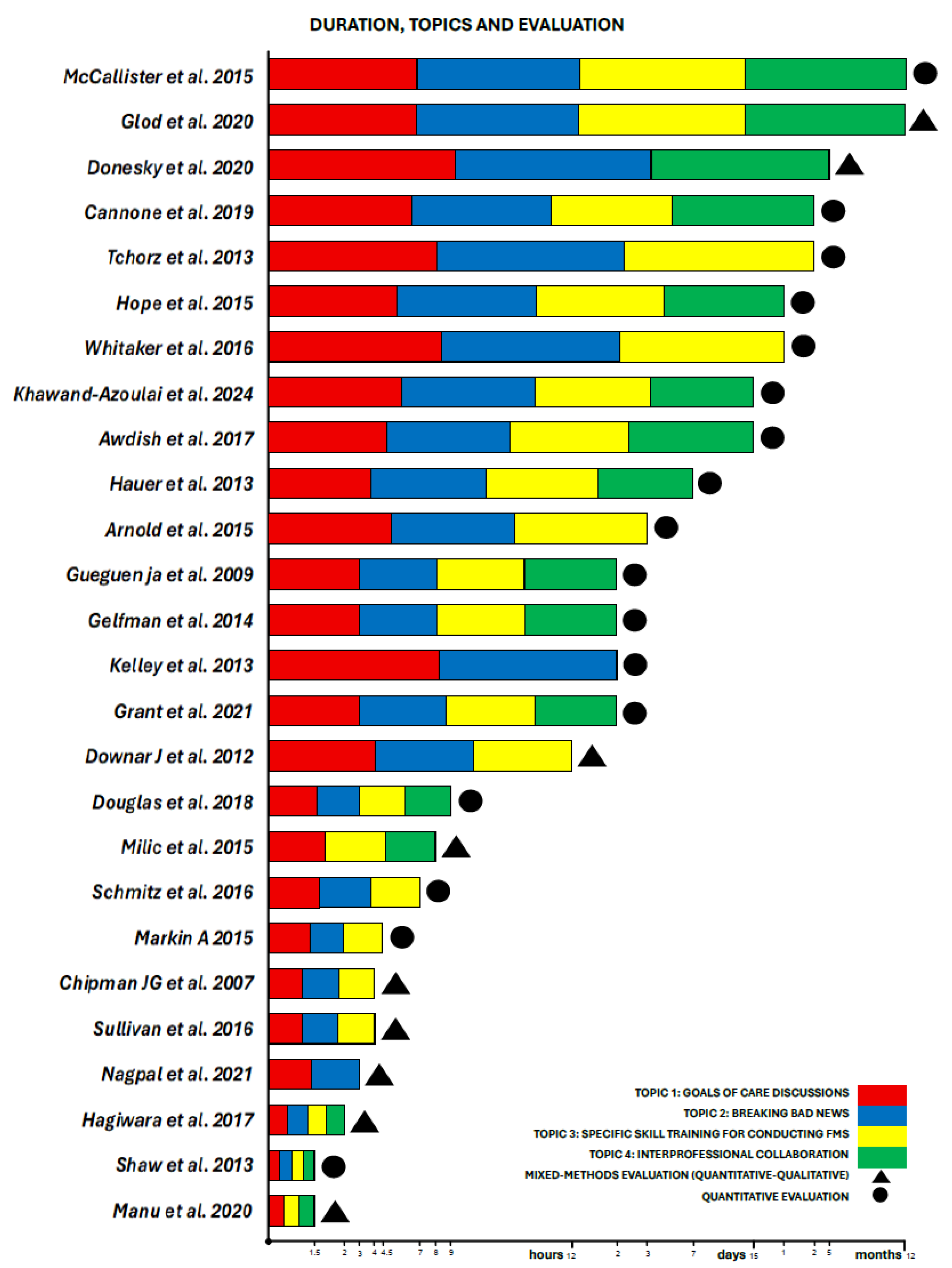

3.5. Intervention

- (i)

- Duration

- (ii)

- Teaching Methods

- (iii)

- Theoretical Framework

- Goals of Care Discussions: It was universally present across all studies, underscoring its critical role in patient-centered care. The discussions often focused on aligning treatment plans with patient preferences and values.

- Breaking Bad News: Reported in 24 out of 26 of the studies [20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], this theme highlighted the challenges and strategies involved in delivering difficult diagnoses or prognoses. Studies such as Khawand-Azoulai et al. [20], Grant et al. [21], and Nagpal et al. [22] emphasized the importance of sensitivity and clarity in these conversations. Moreover, the prognostication was frequently tied to discussions about disease trajectories and treatment expectations. “Code Status Discussions-Do Not Resuscitate/Intubate (DNR/DNI)” was present in ten studies [25,28,30,32,34,36,37,38,42,43]; these discussions were often framed as part of broader goals of care conversations, in critical or end-of-life scenarios. Seven studies focused on the challenges and strategies for transitioning patients to hospice care, often involving sensitive discussions about prognosis and quality of life [22,29,33,35,38,42,44]. Finally, in five studies [20,33,34,40,43], discontinuing life-sustaining treatments involved ethically and emotionally complex decisions.

- Specific skill training for conducting FMs: A significant majority of studies (23/26) [20,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,45] addressing preparation for conducting FMs emphasized the value of preparation before difficult conversations (pre-meeting), including reviewing patient history and anticipating family concerns. Furthermore, conflict mediation was identified as a critical skill for resolving disagreements among families or between families and healthcare teams. All studies addressed the necessity of empathy in healthcare communication. Moreover, the importance of active listening is discussed in 22 of the studies [20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44], with a focus on its role in understanding patient concerns.

3.6. Evaluation of Training

- (i)

- Quantitative evaluation tools and outcomes

- (ii)

- Qualitative evaluations and outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Implication

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDarby, M.; Mroz, E.; Walsh, L.E.; Malling, C.; Chilov, M.; Rosa, W.E.; Kastrinos, A.; McConnell, K.M.; Parker, P.A. Communication Interventions Targeting Both Patients and Clinicians in Oncology: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychooncol. 2025, 34, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-van den Hoek, D.W.; Visser, L.N.C.; Brown, R.F.; Smets, E.M.A.; Henselmans, I. Communication Skills Training for Healthcare Professionals in Oncology over the Past Decade: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, S.; De Panfilis, L.; Costantini, M.; Artioli, G.; Alquati, S.; Di Leo, S. Development and Preliminary Evaluation of a Communication Skills Training Programme for Hospital Physicians by a Specialized Palliative Care Service: The “Teach to Talk” Programme. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, D.K.; Miller, P.A.; Forbes-Thompson, S.A. Communication and End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit: Patient, Family, and Clinician Outcomes. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2005, 28, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moneymaker, K. The Family Conference. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powazki, R.D.; Walsh, D. The Family Conference in Palliative Medicine: A Practical Approach. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2014, 31, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, I.C.; Kawashima, M.; Asch, S.M. Communication with Families Facing Life-Threatening Illness: A Research-Based Model for Family Conferences. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, T.A.; Zaider, T.I.; Li, Y.; Hichenberg, S.; Masterson, M.; Kissane, D.W. Typology of Perceived Family Functioning in an American Sample of Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Zaider, T.I.; Li, Y.; Hichenberg, S.; Schuler, T.; Lederberg, M.; Lavelle, L.; Loeb, R.; Del Gaudio, F. Randomized Controlled Trial of Family Therapy in Advanced Cancer Continued into Bereavement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.E.; Ash, T.; Ochotorena, C.; Lorenz, K.A.; Chong, K.; Shreve, S.T.; Ahluwalia, S.C. A Systematic Review of Family Meeting Tools in Palliative and Intensive Care Settings. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2016, 33, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, S.; Tyrie, L.S.; Bryczkowski, S.; Nagurka, R. Teaching Surgery Residents the Skills to Communicate Difficult News to Patient and Family Members: A Literature Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, A.L.; Arnold, R.M.; Baile, W.F.; Fryer-Edwards, K.A.; Alexander, S.C.; Barley, G.E.; Gooley, T.A.; Tulsky, J.A. Efficacy of Communication Skills Training for Giving Bad News and Discussing Transitions to Palliative Care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, P.J.; Lobb, E.A.; Sanderson, C.; Phillips, J.L. What Is the Evidence for Conducting Palliative Care Family Meetings? A Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, B.A.; Given, C.W.; Sherwood, P.R. Family and Caregiver Needs over the Course of the Cancer Trajectory. J. Support. Oncol. 2012, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W. The Challenge of Family-Centered Care in Palliative Medicine. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2016, 5, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, O.A.; Roberts, B.; Wu, D.S. Interprofessional Interventions to Improve Serious Illness Communication in the Intensive Care Unit: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2023, 40, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawand-Azoulai, M.; Kavensky, E.; Sanchez, J.; Leyva, I.M.; Ferrari, C.; Soares, M.; Zaw, K.M.; van Zuilen, M.H. An Authentic Learning Experience for Medical Students on Conducting a Family Meeting. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2024, 42, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, E.; Sisson, C.B.; Hiatt, T.L.; Stirewalt, F.K.; Crandall, S.J. Family Conference Simulation Designed for Physician Assistant Students and Chaplain Residents. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, V.; Philbin, M.; Yazdani, M.; Veerreddy, P.; Fish, D.; Reidy, J. Effective Goals-of-Care Conversations: From Skills Training to Bedside. MedEdPORTAL 2021, 17, 11122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donesky, D.; Anderson, W.G.; Joseph, R.D.; Sumser, B.; Reid, T.T. TeamTalk: Interprofessional Team Development and Communication Skills Training. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glod, S.A.; Kang, A.; Wojnar, M. Family Meeting Training Curriculum: A Multimedia Approach with Real-Time Experiential Learning for Residents. MedEdPORTAL 2020, 16, 10883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, E.R.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Mullan, P.B.; Vitale, C.A. Eating Problems in Advanced Dementia: Navigating Difficult Conversations. MedEdPORTAL 2020, 16, 11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannone, D.; Atlas, M.; Fornari, A.; Barilla-LaBarca, M.-L.; Hoffman, M. Delivering Challenging News: An Illness-Trajectory Communication Curriculum for Multispecialty Oncology Residents and Fellows. MedEdPORTAL 2019, 15, 10819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P.; Goldschmidt, C.; McCoyd, M.; Schneck, M. Simulation-Based Training in Brain Death Determination Incorporating Family Discussion. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2018, 10, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdish, R.L.; Buick, D.; Kokas, M.; Berlin, H.; Jackman, C.; Williamson, C.; Mendez, M.P.; Chasteen, K. A Communications Bundle to Improve Satisfaction for Critically Ill Patients and Their Families: A Prospective, Cohort Pilot Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hagiwara, Y.; Ross, J.; Lee, S.; Sanchez-Reilly, S. Tough Conversations: Development of a Curriculum for Medical Students to Lead Family Meetings. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2017, 34, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C.C.; Braman, J.P.; Turner, N.; Heller, S.; Radosevich, D.M.; Yan, Y.; Miller, J.; Chipman, J.G. Learning by (Video) Example: A Randomized Study of Communication Skills Training for End-of-Life and Error Disclosure Family Care Conferences. Am. J. Surg. 2016, 212, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.M.; Rock, L.K.; Gadmer, N.M.; Norwich, D.E.; Schwartzstein, R.M. The Impact of Resident Training on Communication with Families in the Intensive Care Unit. Resident and Family Outcomes. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, K.; Kross, E.K.; Hough, C.L.; Hurd, C.; Back, A.L.; Curtis, J.R. A Procedural Approach to Teaching Residents to Conduct Intensive Care Unit Family Conferences. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.M.; Back, A.L.; Barnato, A.E.; Prendergast, T.J.; Emlet, L.L.; Karpov, I.; White, P.H.; Nelson, J.E. The Critical Care Communication Project: Improving Fellows’ Communication Skills. J. Crit. Care 2015, 30, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, A.A.; Hsieh, S.J.; Howes, J.M.; Keene, A.B.; Fausto, J.A.; Pinto, P.A.; Gong, M.N. Let’s Talk Critical. Development and Evaluation of a Communication Skills Training Program for Critical Care Fellows. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markin, A.; Cabrera-Fernandez, D.F.; Bajoka, R.M.; Noll, S.M.; Drake, S.M.; Awdish, R.L.; Buick, D.S.; Kokas, M.S.; Chasteen, K.A.; Mendez, M.P. Impact of a Simulation-Based Communication Workshop on Resident Preparedness for End-of-Life Communication in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 534879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallister, J.W.; Gustin, J.L.; Wells-Di Gregorio, S.; Way, D.P.; Mastronarde, J.G. Communication Skills Training Curriculum for Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellows. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milic, M.M.; Puntillo, K.; Turner, K.; Joseph, D.; Peters, N.; Ryan, R.; Schuster, C.; Winfree, H.; Cimino, J.; Anderson, W.G. Communicating with Patients’ Families and Physicians About Prognosis and Goals of Care. Am. J. Crit. Care 2015, 24, e56–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfman, L.P.; Lindenberger, E.; Fernandez, H.; Goldberg, G.R.; Lim, B.B.; Litrivis, E.; O’Neill, L.; Smith, C.B.; Kelley, A.S. The effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course: A real-time assessment of skill acquisition and deliberate practice. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 738–744.e1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, K.E.; Soni, K.; Cornett, P.; Kohlwes, J.; Hollander, H.; Ranji, S.R.; Ten Cate, O.; Widera, E.; Calton, B.; O’Sullivan, P.S. Developing Entrustable Professional Activities as the Basis for Assessment of Competence in an Internal Medicine Residency: A Feasibility Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.S.; Back, A.L.; Arnold, R.M.; Goldberg, G.R.; Lim, B.B.; Litrivis, E.; Smith, C.B.; O’Neill, L.B. Geritalk: Communication Skills Training for Geriatric and Palliative Medicine Fellows. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.J.; Davidson, J.E.; Smilde, R.I.; Sondoozi, T.; Agan, D. Multidisciplinary Team Training to Enhance Family Communication in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchorz, K.M.; Binder, S.B.; White, M.T.; Lawhorne, L.W.; Bentley, D.M.; Delaney, E.A.; Borchers, J.; Miller, M.; Barney, L.M.; Dunn, M.M.; et al. Palliative and End-of-Life Care Training during the Surgical Clerkship. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 185, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downar, J.; Knickle, K.; Granton, J.T.; Hawryluck, L. Using Standardized Family Members to Teach Communication Skills and Ethical Principles to Critical Care Trainees. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 1814–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueguen, J.A.; Bylund, C.L.; Brown, R.F.; Levin, T.T.; Kissane, D.W. Conducting Family Meetings in Palliative Care: Themes, Techniques, and Preliminary Evaluation of a Communication Skills Module. Palliat. Support. Care 2009, 7, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipman, J.G.; Beilman, G.J.; Schmitz, C.C.; Seatter, S.C. Development and Pilot Testing of an OSCE for Difficult Conversations in Surgical Intensive Care. J. Surg. Educ. 2007, 64, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E.A.; Kudelka, A.P. SPIKES-A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, S.; Buonaccorso, L.; Tanzi, S.; Balestra, G.L.; Ghirotto, L. Between host country and homeland: A grounded theory study on place of dying and death in migrant cancer patients. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Jerzmanowska, N.; Thristiawati, S.; Green, M.; Lobb, E.A. Culturally and linguistically diverse palliative care patients’ journeys at the end-of-life. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.; Strickland, K.; Gibson, J. Cultural considerations at end-of-life for people of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: A critical interpretative synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaider, T.I.; Kissane, D.W.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Masterson, M. Cancer-related communication during sessions of family therapy at the end of life. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, T.W.; Lambert, S.D.; Kelly, B.; Falconier, M.; Kissane, D.; Levesque, J.V. Couples coping with cancer: Exploration of theoretical frameworks from dyadic studies. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Quinn, K.; O’Hanlon, B.; Aranda, S. Family Meetings in Palliative Care: Multidisciplinary Clinical Practice Guidelines. BMC Palliat. Care 2008, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year, State | Objective | Study Design | Trainer(s) | Trainees | Setting | Duration | Teaching Methods | Theoretical Framework | Quantitative Evaluation | Quantitative Outcomes | Qualitative Evaluation | Qualitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khawand-Azoulai et al., 2024 USA [20] | To provide an overview of a curriculum focused on end-of-life discussions and report outcomes from an advanced preparation assignment and student evaluations. | Pre/post interventional study. | Palliative medicine physicians and fellows, geriatricians, nurses (geriatrics and palliative), a social worker and a psychologist (number unspecified). | Medical students (n = 80) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (attending final year and participating in a “Transitioning to Residency” course). | University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA (Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Department of Medical Education). | Embedded within a 2-week course, the specific intensive training comprises 2 h of pre-session preparation and 1 h of virtual session. |

| Simulation-based learning with interprofessional education (IPE) elements. Program:

|

|

| N/A | N/A |

| Grant et al., 2021 USA [21] |

| Pre/post interventional study (with two cohorts). | Faculty team that included PAs and chaplains with experience in simulation design, critical care, advance care planning, and education expertise (number unspecified). | PA students (n = 171) and chaplain residents (n = 20). | Simulation labs at Wake Forest School of Medicine: Emergency department and Family Conference scenarios. | Two-day event, conducted across two years Day 1: Clinical case (60 min) + debrief (10 min) Day 2: Family conference (25–30 min) + large-group debrief. |

| In-person Simulation-based IPE Program: Day 1 Simulated cases in an emergency department setting with a high-fidelity mannequin; Day 2 Simulated family conference focusing on delivering poor prognosis and end-of-life decision-making, addressing spiritual dissonance. | Surveys: Five-point Likert scale (pre/post) assessing confidence in prognosis delivery, IPE value, chaplain/PA roles. |

| N/A | N/A |

| Nagpal et al., 2021 USA [22] | To train internal medicine (IM) residents in goals-of-care (GOC) conversations near end of life using

| Pre/post interventional study with follow-up (no control group. | Faculty: Six total (hospitalists and/or palliative care clinicians with teaching experience), with three facilitating per session. | Second-year IM residents (n = 84). | Simulation Center at University of Massachusetts Medical School: Exam rooms (simulated hospital setting with video recording). Bedside: Real patient encounters during inpatient rotations (Mini-CEX evaluations). | Simulation session: 3 h (resident training) Preparatory meetings: 2 h (for SPs and faculty, held separately). |

| In-person

| Pre- and post-session self-assessment surveys (follow-up surveys at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months); Mini-CEX (faculty-rated skills); Patient surveys. |

|

| Resident-reported themes:

|

| Donesky et al., 2020 USA [23] | To report on the development, exploratory outcomes, and lessons learned from a pilot project, TeamTalk, which taught team-based communication skills using an adapted VitalTalk training methodology. | Pre/post study with qualitative data (no control group). | Interprofessional faculty team trained as VitalTalk facilitators (number unspecified). | Nurses, chaplains, and physicians (61 learners over two years). |

| Two years of course

| High-fidelity simulations (role-play with actors); Skills/capacities handout: adapted from VitalTalk for team communication. | Interactive workshop with VitalTalk methodology; Interprofessional team development and communication skills training. |

| Interprofessional collaboration attitudes and self-reported confidence. |

| Interprofessional dialog; skill development; role clarity across professions. |

| Glod et al., 2020 USA [24] | To address the problem of insufficient family meeting communication skills training by developing a curriculum for graduate medical trainees that provided learning around facilitation of family meetings during the MICU rotation. | Pre/post interventional study (no control group). | Members of the palliative care service, a social worker, a nurse care coordinator, and an ICU attending or ICU fellow (number unspecified). | 34 internal medicine residents. | Medical ICU (MICU) at Penn State College of Medicine’s academic hospital. | Full curriculum cycle: 12 months; Part 1: 1 h; Part 3: 30 min. |

| Multimodal Part 1: Introductory interactive session Part 2: Interactive computer-based modules Part 3: MICU introduction session Part 4: family meeting facilitation with self-reflection, peer feedback, and self-assessment. |

|

| Self-efficacy survey (open-ended questions). |

|

| Manu et al., 2020 USA [25] | To improve internal medicine residents’ confidence and skills in addressing eating problems in advanced dementia through an interactive seminar featuring a trigger video and small-group discussion. | Pre/post interventional study (no control group). | Faculty clinician educators: geriatrics/palliative care experts (number unspecified). | IM/medicine-pediatrics/neurology residents (n = 82 of 106 participants). | University of Michigan Medical School (IM/medicine-pediatrics residency program); Medical school classroom. | Monthly seminar; video and small-group discussion: 90 min. |

| Multimodal

| Pre/post survey using Likert scale (1–4) to assess perceived independence. |

| Open-ended text feedback from participants (thematic analysis). | Clinical relevance, group dynamics, seminar format/video quality. |

| Cannone et al., 2019 USA [26] | To improve communication skills in trainees, specifically in oncology, palliative care, and hospice settings, by providing a safe environment to learn and practice these skills. | Pre/post interventional study. | Faculty members: attending physicians in the hematology and oncology, pediatric hematology and oncology, and hospice and palliative care programs. Nine total | Palliative and oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents (n = 22) | Educational setting: a classroom for didactic sessions and small meeting rooms for role-play exercises. OSCEs (Simulation Center) Location: Center for Learning and Innovation (CLI), Lake Success, NY. | Overall: 8–9 weeks (2 months). Specifics: Weekly 2 h sessions; Pre/post OSCEs (30 min encounters). |

| Multimodal didactic modules: Eight PowerPoint sessions; Role-play: longitudinal “hot-seat” scenarios with faculty acting as the same patient; OSCEs: pre/post videotaped assessments with standardized patients (SPs). |

|

| N/A | N/A |

| Douglas et al., 2018 USA [27] | To develop a simulation-based training program to teach neurology residents how to accurately diagnose brain death and effectively communicate this diagnosis to the patient’s family with empathy. | Prospective, pre/post interventional study (no control group). | Three neurology attending physicians; 1–2 palliative care attending physicians; Support staff (Simulation nurse and technicians). | 18 neurology residents over three years. | Loyola University Medical Center (Chicago). | Three half-days: 4 h pre/post intervention assessments and 5 h didactic intervention. |

|

| Clinical skills checklist (15 items); Apnea test checklist (9 items); communication skills checklist (37 items). Limitation: Checklists unvalidated (author-developed). | Technical and communication skills. | N/A | N/A |

| Awdish et al., 2017 USA [28] | To determine the feasibility of using a communications bundle to improve patient/family satisfaction and to assess whether the bundle impacted trainee self-perception of communication skills in end-of-life situations. | Prospective cohort feasibility study with control group (pilot). | Physicians, nurses, and fellows trained in VitalTalk and the communications bundle (number unspecified). | MICU Staff (physicians, fellows, residents). | Hospital Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU). | Overall: 2 weeks. |

| Four-step bundle:

|

|

| N/A | N/A |

| Hagiwara et al., 2017 USA [29] | To describe the development and results of a training and assessment program about leading a family meeting. | Single-arm educational intervention with pre/post assessment. | Palliative care faculty preceptors; standardized patient (SP) actors; Clinical skills center staff (number unspecified). | 674 fourth-year medical students. | University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA). | Total time:135 min. | Online didactics (60 min); Small-group role-play (1 h); In-person FM-OSCE with actors (15 min/student). | Family meeting leadership training for medical students:

| FM-OSCE (Family Meeting Objective Structured Clinical Examination) checklist: 15 domains scored on a 1–5 Likert scale. |

| Thematic analysis by two independent investigators. Data Sources:

| Discussing prognosis clearly and directly, explaining palliative care and hospice, avoiding medical jargon, discussing cultural and religious preferences. |

| Schmitz et al., 2016 USA [30] | To develop and test communication skills intervention for surgical residents using videotapes of end-of-life (EOL) and error disclosure (ED) encounters. | Pre/post interventional study with stratified randomization (control group). | Surgery and orthopedic faculty (number unspecified). | 72 PGY1 and PGY3 residents from general surgery and orthopedic programs. | Academic medical center (surgery and orthopedic departments) at the University of Minnesota and Mayo Clinic. | Total intervention time: ~7 h (5 online + 2 in-person). |

| Multimodal simulation-based training: 10 video-based online modules; two face-to-face sessions (EOL and ED) with faculty, featuring role-playing and feedback. OSCE assessments: pre- and post-test simulations with SPs. |

| Total group: no significant treatment effects (low online engagement and brief face-to-face time); Subgroup effects: low-performing residents showed significant improvement. | N/A | N/A |

| Sullivan et al., 2016 USA [31] | To assess the impact of a communication training program on resident skills in communicating with families in an ICU and on family outcomes. | Prospective, single-site educational intervention study (pre/post interventional). | Critical care physicians (number unspecified). | 160 internal medicine residents. | Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA: Intensive Care Unit (ICU). | 4 h total: two 1 h morning sessions and a 2 h afternoon session. |

| Multimodal: Interactive discussions;

|

|

|

| Family member themes:

|

| Whitaker et al., 2016 USA [32] | To determine the acceptability and feasibility of a procedure-training module for teaching ICU family conferences to residents. | Pilot feasibility study (no control group; no pre/post evaluation). | ICU faculty and fellows (number unspecified). | 27 internal medicine residents (15 interns, 12 PGY-3) during ICU rotations. | Medical ICU at a single academic teaching hospital. | One-month ICU rotation per resident. |

| Five components module:

| Survey: 10-item anonymous survey (Likert-scale ratings + open comments). |

| N/A | N/A |

| Arnold et al., 2015 USA [33] | To develop and evaluate a 3-day communication skills workshop for ICU fellows, aimed at improving skills in delivering bad news, conducting FMs, and discussing GOC. | Pre/post interventional study with self-assessment surveys (no control group). | Faculty facilitators: palliative care, critical care, and communication experts (number unspecified). | 38 pulmonary/critical care and critical care medicine fellows (first- and second-year) from a single institution. | Off-site 3-day retreat (away from clinical duties). | Three consecutive days | Skills-based workshop modeled after Oncotalk and focused on active learning (role-play simulation, feedback, reflection). |

| Pre/post surveys: 11 communication skills rated on five-point Likert scales; 1-month follow-up survey (self-reported skill memory). | Self-rated skills (e.g., giving bad news and conducting family conferences). | N/A | N/A |

| Hope et al., 2015 USA [34] | To develop and evaluate a communication skills program for critical care fellows, integrating simulation, didactics, and feedback to improve family meeting proficiency. | Pre/post interventional study (no control group.) | Critical care and palliative care faculty (five attending physicians, three with palliative care fellowship training); Clinician volunteers (nurses, physicians). | 31 critical care fellows (28 participated in simulations) over three years. | Montefiore Medical Center at Albert Einstein College of Medicine: division of Critical Care Medicine. | One month per cohort (repeated annually over three years); Two simulation afternoons (beginning and end of month) lasting ~3 h. |

| Multimodal learning: Simulation + didactics + real-time feedback;

|

| Agenda-setting, summarizing care, follow-up plans. | N/A | N/A |

| Markin A 2015 USA [35] | To improve residents’ EOL communication skills via a brief simulation-based workshop (VitalTalk method). | Pre/post interventional (no control group). | Two faculty facilitators (physicians) trained in VitalTalk. | 34 s-year internal medicine residents (PGY-2). | Academic medical center ICU at the Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit, MI). | 3-day VitalTalk workshops for faculty members; Three 90 min sessions for residents; 9-month follow-up. |

| VitalTalk curriculum

| Pre- and post-survey with five-point Likert scales (self-assessed preparedness). |

| N/A | N/A |

| McCallister et al., 2015 USA [36] | To evaluate the effectiveness of a communication skills curriculum for pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) fellows, using formative feedback (Family Meeting Behavioral Skills Checklist) to improve family meeting skills in the ICU. | Prospective pre/post quasi-experimental interventional study (control group). | Palliative medicine faculty supervisors with expertise in communication skills and critical care + psychologists (number unspecified). | 11 first-year PCCM fellows (intervention group); 5 s-year fellows (historical controls). | Setting integrated into the first year of PCCM fellowship: academic MICU. Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH. | 12-month curriculum; 3 h workshop + FMs. |

| Multimodal Behavioral skills-based curriculum:

|

| Behavioral skills and confidence. | N/A | N/A |

| Milic et al., 2015 USA [37] | To improve critical care nurses’ skills and confidence to engage in discussions with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care by using a focused educational intervention. | Pre/post interventional (no control group). | Interdisciplinary working group: ICU bedside nurses, a critical care nurse researcher and educator, a palliative care physician, a critical care and palliative care physician, and a palliative care chaplain and psychologist. | 82 critical care nurses, 15 per workshop. | Academic medical center: University of California San Francisco Medical Center. | 8 h workshop; 3× role-plays (60–70 min each). |

| Communication skills-focused:

| Four-point Likert-type scale for 14- to 22-item surveys. |

| Focus group (n = 11) + open-ended survey responses. Thematic analysis of impact. | Themes:

|

| Gelfman et al., 2014 USA [38] | To evaluate the effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course by comparing pre- and post-course real-time assessment of participants leading family meetings and to evaluate participants’ sustained skills practice. | Pre/post interventional (no control group). | Six course faculty: physicians on the Geriatric Medicine and Palliative care hospital services. | Nine first-year fellows (five palliative medicine, four geriatrics). | Academic medical centers: Mount Sinai Medical Center and the James J. Peters Bronx VA Medical Center. | Overall: 2-day workshop + 2-month follow-up. Specifics: Didactics (4 h) + small-group simulations (8 h). Clinical assessments: Pre/post family meetings (~42 min each). |

| Didactic-experiential:

|

|

| N/A | N/A |

| Hauer et al., 2013 USA [39] | To describe a pilot and feasibility evaluation of two Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for competency-based assessment in internal medicine (IM) residency. | Pilot feasibility study (pre/post intervention design with surveys). No control group. | Leadership group: Residency program director, associate chair for education, chief residents, and faculty with medical education expertise. Faculty developers: Palliative care faculty (for family meeting EPA); hospital medicine faculty (for Discharge EPA). (number unspecified). | 26 PGY-1 internal medicine residents (involved in the family meeting EPA assessment and related surveys). | General: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) IM residency program. Particular:

| Discharge EPA Overall: Integrated into four-week rotation. Specifics: Didactics (1 h discharge summary lecture, 2 × 1 h noon conferences). Family meeting EPA Overall: 1-week rotation. Specifics: 1 h noon conference, online modules, critical reflection exercise. |

| Multimodal (didactic + workplace-based assessment):

| Surveys (Likert-scale questions); Completion rates of EPA assessments. |

| N/A | N/A |

| Kelley et al., 2013 USA [40] | To develop and evaluate an intensive communication skills training course for geriatrics and palliative medicine fellows (Geritalk). | Single-arm pre/post interventional (no control group). Pilot study with mixed-methods evaluation (surveys + open-ended feedback) | Six course faculty trained in small-group facilitation techniques: attending physicians on the Geriatric Medicine and Palliative Care hospital services. | Geriatrics and palliative medicine fellows (n = 16). | N/A | Overall: 2 days Specifics Large-group didactics: 25 min lectures (four sessions). Small-group practice: 2.5 h sessions (four sessions). |

| Simulation-based retreat drawn upon the Oncotalk method.

| Surveys: Pre/post self-assessed preparedness (five-point Likert scale); Post-retreat satisfaction (five-point Likert scale): 2-month follow-up on skills practice frequency. | Overall satisfaction; Self-assessed preparedness for communication challenges; Sustained skills practice. | N/A | N/A |

| Shaw et al., 2013 USA [41] | To train multidisciplinary teams of ICU caregivers in communicating with the families of critically ill patients, to improve staff confidence as well as family satisfaction. | Pre/post interventional study (no control group). | N/A | 98 ICU physicians and hospital staff (intensivists, medical residents, ICU chaplains, nurses, social workers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and case managers). | Community hospital (Scripps Mercy Hospital, San Diego) medical and surgical ICUs. | Overall: 14 sessions conducted between May–September 2011. Specifics: 90 min sessions (didactic + simulation + debrief). |

| Multidisciplinary team training in a four-step bundle:

|

|

| N/A | N/A |

| Tchorz et al., 2013 USA [42] | To ensure exposure to the communication skills needed to effectively manage complex palliative and end-of-life care scenarios commonly encountered during each surgical clerkship rotation. | Pre/post interventional (single-group, no control). | Faculty members (debriefing facilitators): One ethicist; one geriatrician. Student evaluators: Seven full-time WSU-BSOM surgeons. | 97 Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine (WSU-BSOM) third-year medical students, during their surgical clerkship. | Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine (WSU-BSOM): clinical settings included Trauma, Intensive Care Unit, Transplant, and Surgical Oncology clinical services (from Skills and Assessment Training Center). | Overall: 8-week surgical clerkship; Specific: OSCEs conducted during Week 4 of the 8-week clerkship; 1 h for all six OSCE stations; 10 min per OSCE station (student–patient interaction), 2 min between stations. 1 h group debriefing after all OSCEs. |

| Multimodal didactic (online modules) + simulation (OSCEs):

|

| Mean percent scores for each of the six OSCE scenarios; Total score for the six scenarios. | N/A | N/A |

| Downar J et al., 2012 Canada [43] | To determine the effectiveness of standardized family members (SFMs) for improving communication skills and ethical/legal knowledge of senior ICU trainees. | Multimodal evaluation of mixed-methods educational intervention (Pre/post quantitative tests + planned qualitative debriefing/feedback). | Staff intensivists, communication skills educators, and standardized family members (SFMs) from the standardized patient program at the University of Toronto (number unspecified). | 51 Postgraduate subspecialty Critical Care Medicine trainees. | Postgraduate Critical Care Medicine academic program at the University of Toronto. | Half-day workshop; 60 min didactic session; Four 45 min simulated family meetings; 15 min for feedback and completion of the evaluation forms; 1-yr follow-up scenario; 5-year period workshop. |

| Multimodal didactic + simulation

|

|

|

|

|

| Gueguen ja et al., 2009 USA [44] | To develop and evaluate a communication skills training module for healthcare professionals on conducting family meetings in palliative care, assessing self-efficacy and satisfaction post-training. | Pre/post interventional study (retrospective). | Communication Skills Training and Research Laboratory (Comskil) at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The final author (psychiatrist D.W.K.) facilitated a role-play. | 40 multi-specialty healthcare professionals (medical/surgical/radiation oncology, pediatrics, palliative care); Nurses/nurse practitioners, physician assistants. | Communication Skills Training and Research Laboratory (Comskil) at MSKCC and other New York City Metropolitan-area hospitals. | Two-day course for 77% of participants (those new to the Comskil curriculum). | In-person didactic presentation and “fishbowl” role-play with simulated family members. | Multimodal didactic + simulation

| Retrospective pre/post surveys (Likert three- and five-points scales). |

| N/A | N/A |

| Chipman JG et al., 2007 USA [45] | To describe the development and results of an Objective Structured Clinical Exam (OSCE) for leading family conferences in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU). | Pilot demonstration and reliability assessment. | Surgical Critical Care Faculty; Interdisciplinary Raters: Four ICU nurses, one neurologist, two additional surgeons, one educator. | PGY-2 and PGY-4 categorical general surgery residents (n = 8) | University of Minnesota Medical School (academic teaching hospital): Inter-professional Educational Resource Center (IERC) with standardized exam rooms and video recording. | OSCE Session Duration per resident: Two 20 min stations + 45 min pre-lecture. The entire testing period: 4 h. |

| Simulation-based OSCE

| Two rating scales (EOL + Disclosure): four-point Likert items and dichotomous checklists. |

|

| Resident feedback themes:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alquati, S.; Buonaccorso, L.; Asensio Sierra, N.M.; Sassi, F.; Venturelli, F.; Bassi, M.C.; Scialpi, S.D.; Tanzi, S. Improving Advanced Communication Skills Towards the Family System: A Scoping Review of Family Meeting Training in Oncology and Other Healthcare Settings. Cancers 2025, 17, 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193115

Alquati S, Buonaccorso L, Asensio Sierra NM, Sassi F, Venturelli F, Bassi MC, Scialpi SD, Tanzi S. Improving Advanced Communication Skills Towards the Family System: A Scoping Review of Family Meeting Training in Oncology and Other Healthcare Settings. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193115

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlquati, Sara, Loredana Buonaccorso, Nuria Maria Asensio Sierra, Francesca Sassi, Francesco Venturelli, Maria Chiara Bassi, Stefano David Scialpi, and Silvia Tanzi. 2025. "Improving Advanced Communication Skills Towards the Family System: A Scoping Review of Family Meeting Training in Oncology and Other Healthcare Settings" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193115

APA StyleAlquati, S., Buonaccorso, L., Asensio Sierra, N. M., Sassi, F., Venturelli, F., Bassi, M. C., Scialpi, S. D., & Tanzi, S. (2025). Improving Advanced Communication Skills Towards the Family System: A Scoping Review of Family Meeting Training in Oncology and Other Healthcare Settings. Cancers, 17(19), 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193115