Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carboplatin/Gemcitabine Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer: A Single UK Centre Experience

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Treatment

2.4. Assessments

2.5. Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

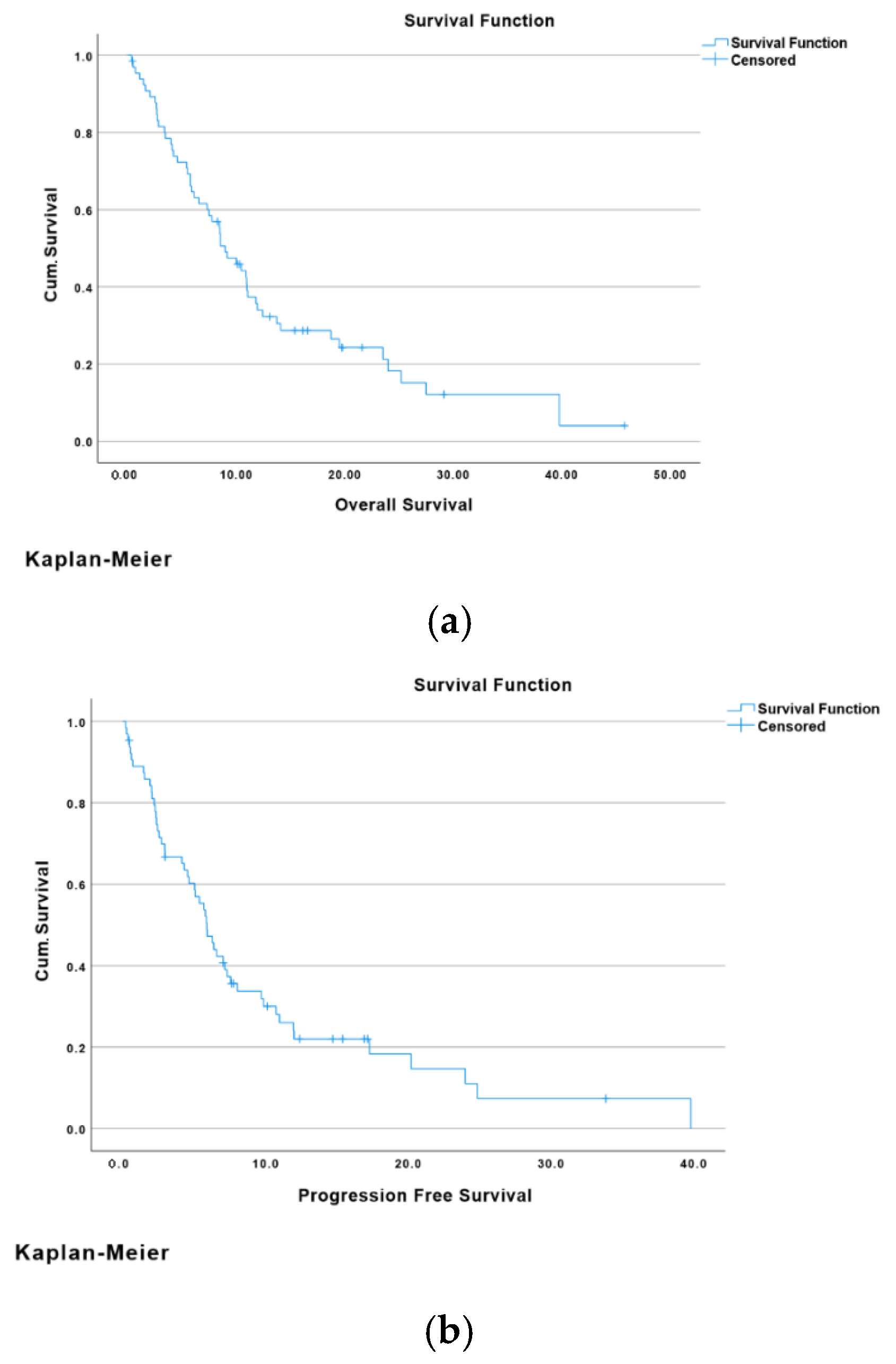

3.2. Outcome: Overall Survival and Progression-Free Survival

Overall Survival and Progression-Free Survival

3.3. Tumour Response and Survival Status

Disease Control Rate

3.4. Toxicity Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Dong, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Mei, Q.; Han, W. Efficacy and biomarker analysis of nivolumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with unresectable or metastatic biliary tract cancers: Results from a phase II study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, V.P.K.; Talwar, V.; Raina, S.; Goel, V.; Dash, P.K.; Bajaj, R.; Sharma, M.; Medisetty, P.; Ram, D.; Agrawal, C.; et al. Gemcitabine with carboplatin for advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A study from North India Cancer Centre. Indian J. Cancer 2018, 55, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano-Bonilla, L.; Mohamed, E.A.; Mounajjed, T.; Roberts, L.R. Biliary tract cancers: Epidemiology, molecular pathogenesis, and genetic risk associations. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.W.; Kelley, R.K.; Nervi, B.; Oh, D.-Y.; Zhu, A.X. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet 2021, 397, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, J.-B.; Niu, Y.; Dong, L.; Du, L.; Wang, C. Tissue-engineered edible bird’s nests (TeeBN). Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Disease burden of biliary tract cancer in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: A comprehensive demographic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Chin. Med J. 2024, 137, 3117–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Yuan, S.; Huang, S.; Fu, Y.; Yan, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; et al. The epidemiological trends of biliary tract cancers in the United States of America. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, P.L.; Goodchild, G.; Pereira, S.P. Molecular Pathogenesis of Cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarca, A.; Barriuso, J.; McNamara, M.G.; Valle, J.W. Molecular targeted therapies: Ready for “prime time” in biliary tract cancer. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, G.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, W.; Li, S.; Pan, G.; Chen, X. The global, regional, and national burden of gallbladder and biliary tract cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Cancer 2021, 127, 2238–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.; Bridgewater, J.; Edeline, J.; Kelley, R.; Klümpen, H.; Malka, D.; Primrose, J.; Rimassa, L.; Stenzinger, A.; Valle, J.; et al. Biliary tract cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebata, T.; Hirano, S.; Konishi, M.; Uesaka, K.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kaneoka, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Ambo, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy versus observation in resected bile duct cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J.B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, J.; Wasan, H.; Palmer, D.H.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, A.; Maraveyas, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Iveson, T.; Hughes, S.; Pereira, S.P.; et al. Cisplatin plus Gemcitabine versus Gemcitabine for Biliary Tract Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-Y.; He, A.R.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.-T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Lee, M.A.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Sendilnathan, A.; Siddiqi, N.I.; Gulati, S.; Ghose, A.; Xie, C.; Olowokure, O.O. Advanced biliary tract cancer: Clinical outcomes with ABC-02 regimen and analysis of prognostic factors in a tertiary care center in the United States. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 6, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgewater, J.; Lopes, A.; Palmer, D.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, A.; Maraveyas, A.; Madhusudan, S.; Iveson, T.; Valle, J.; Wasan, H. Quality of life, long-term survivors and long-term outcome from the ABC-02 study. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Takeda, T.; Okamoto, T.; Ozaka, M.; Sasahira, N. Chemotherapy for Biliary Tract Cancer in 2021. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Natarajan, G.; Malathi, R.; Holler, E. Increased DNA-binding activity of cis-1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylatodiammineplatinum(II) (carboplatin) in the presence of nucleophiles and human breast cancer MCF-7 cell cytoplasmic extracts: Activation theory revisited. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.; Bellmunt, J.; Mead, G.; Kerst, J.M.; Leahy, M.; Maroto, P.; Gil, T.; Marreaud, S.; Daugaard, G.; Skoneczna, I.; et al. Randomized Phase II/III Trial Assessing Gemcitabine/Carboplatin and Methotrexate/Carboplatin/Vinblastine in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Cancer Who Are Unfit for Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy: EORTC Study 30986. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozols, R.F.; Bundy, B.N.; Greer, B.E.; Fowler, J.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.; Burger, R.A.; Mannel, R.S.; DeGeest, K.; Hartenbach, E.M.; Baergen, R.; et al. Phase III Trial of Carboplatin and Paclitaxel Compared with Cisplatin and Paclitaxel in Patients with Optimally Resected Stage III Ovarian Cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3194–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.; Brandi, G. First-line Chemotherapy in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer Ten Years After the ABC-02 Trial: “And Yet It Moves!”. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 27, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuette, W.; Blankenburg, T.; Schneider, C.P.; von Weikersthal, L.F.; Guetz, S.; Laier-Groeneveld, G.; Virchow, J.C.; Chemaissani, A.; Reck, M. Randomized, multicenter, open-label phase II study of gemcitabine plus single-dose versus split-dose carboplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2006, 8, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.G.; Song, H.S.; Lee, M.A.; Nam, E.M.; Lim, J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, K.T.; Zang, D.Y.; Jang, J.-S. Treatment outcomes of gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus platinum for advanced biliary tract cancer: A Korean Cancer Study Group retrospective analysis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 74, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Rankin, C.J.; Ben-Josef, E.; Lenz, H.-J.; Gold, P.J.; Hamilton, R.D.; Govindarajan, R.; Eng, C.; Blanke, C.D. SWOG 0514: A phase II study of sorafenib in patients with unresectable or metastatic gallbladder carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Investig. New Drugs 2011, 30, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okusaka, T.; Ishii, H.; Funakoshi, A.; Yamao, K.; Ohkawa, S.; Saito, S.; Saito, H.; Tsuyuguchi, T. Phase II study of single-agent gemcitabine in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005, 57, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, J.; Riecken, B.; Kummer, O.; Lohrmann, C.; Otto, F.; Usadel, H.; Geissler, M.; Opitz, O.; Henß, H. Outpatient chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.; Picus, J.; Trinkhaus, K.; Fournier, C.C.; Suresh, R.; James, J.S.; Tan, B.R. Gemcitabine with carboplatin for advanced biliary tract cancers: A phase II single-institution study. HPB 2010, 12, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shroff, R.T.; Kennedy, E.B.; Bachini, M.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Crane, C.; Edeline, J.; El-Khoueiry, A.; Feng, M.; Katz, M.H.; Primrose, J.; et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Biliary Tract Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuse, J.; Kasuga, A.; Takasu, A.; Kitamura, H.; Nagashima, F. Role of chemotherapy in treatments for biliary tract cancer. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 2012, 19, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baraka, B.; Ponda, D.J.; Hanna, J.; Gomez, D.; Aithal, G.; Arora, A. Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carboplatin/Gemcitabine Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer: A Single UK Centre Experience. Cancers 2025, 17, 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193102

Baraka B, Ponda DJ, Hanna J, Gomez D, Aithal G, Arora A. Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carboplatin/Gemcitabine Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer: A Single UK Centre Experience. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaraka, Bahaaeldin, Dwiti Jatin Ponda, Jennifer Hanna, Dhanny Gomez, Guruprasad Aithal, and Arvind Arora. 2025. "Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carboplatin/Gemcitabine Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer: A Single UK Centre Experience" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193102

APA StyleBaraka, B., Ponda, D. J., Hanna, J., Gomez, D., Aithal, G., & Arora, A. (2025). Efficacy and Toxicity Profile of Carboplatin/Gemcitabine Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer: A Single UK Centre Experience. Cancers, 17(19), 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193102