Simple Summary

This study provides an up-to-date estimate of Australia’s cancer burden attributable to modifiable risk factors. The results highlighted that one third of cancer deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost are preventable through addressing common risk factors. This research is timely, comprehensive in its scope of risk factors and cancer types, uses DALYs for a holistic cancer burden assessment, and includes detailed sex-specific analysis. The results provide crucial evidence for targeted public health measures that reduce preventable risks.

Abstract

Understanding the relative contribution of modifiable risk factors to cancer morbidity and mortality is crucial for designing effective cancer prevention and control strategies. Our study estimated cancer-related deaths and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in Australia using data from the Global Burden of Diseases 2021 study. In 2021, an estimated 20,409 cancer deaths (37.5%) and 431,575 cancer DALYs lost (37.9%) in Australia were attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors. Males had higher modifiable risk attributed to cancer death and DALY rates than females. Behavioral risks accounted for 25.0% of cancer deaths and 26.5% of DALYs. Metabolic risks and environmental/occupational risks accounted for 9.4% and 9.3% of deaths, respectively. Smoking remained the leading attributable risk factor, accounting for 12.2% cancer deaths and 13.1% DALYs lost. Dietary risks accounted for 40.0% of colorectal cancer deaths and DALYs lost. Cervical, larynx, liver, lung, and colorectal cancers had a high proportion of deaths and DALYs lost attributed to modifiable risks. Liver and nasopharyngeal cancers had the highest burden attributed to alcohol use (39.1% and 39.0%, respectively), while 21.3% liver cancer deaths were attributed to drug use. Strengthening public health interventions, such as multi-disciplinary approaches to promote a healthy lifestyle, is required.

1. Introduction

While advancements in diagnosis and treatment have improved cancer outcomes, the overall burden of cancer continues to grow [1]. A substantial portion of this burden is attributable to modifiable risk factors that encompass a wide range of lifestyle factors and environmental exposures [1,2,3]. Targeting these modifiable risk factors is likely to provide one of the most effective and cost-efficient strategies for reducing both cancer incidence and mortality [4]. Understanding the magnitude of these preventable cancer burdens is therefore crucial for informing public health strategies and reducing the impact of cancer on population health.

An extensive body of research from Australia has explored the contribution of various risk factors to cancer incidence and mortality [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, this literature has largely focused on a limited number of cancer types and specific risk factors, predominantly smoking, alcohol, and overweight/obesity [5,6,7,9,10,11,12,14,16]. Few studies have investigated the contribution of modifiable risk factors to the non-fatal burden of cancer (disability) [6,17]. Overall, recent detailed evidence within the Australian/local context is lacking—this is particularly important given that attributable risks vary significantly by setting (e.g., sociocultural, environmental, economic, and health system responses). The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) framework provides a unique opportunity for analysis of the proportion of cancer deaths and cancer-related burden attributable to a wide range of risk factors for a more comprehensive list of cancer types. Yet, no recent GBD studies have explored this for the Australian population. While recent GBD studies have examined disease burden and risk factors globally or within Australia, they often lack sufficient detail. Some analyses are limited by a lack of cancer-specific information [18,19], a focus on specific age groups [18], or do not disaggregate results at the national level for Australia [1,20]. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive and nationally tailored analysis of modifiable cancer risk factors in Australia. The most recent comprehensive study, using GBD2015 data [17], assessed the broader impact of behavioral/lifestyle risks and environmental/occupational exposures on the overall cancer burden in Australia. Given shifts in population risk profiles, including the potential impacts of screening, diagnoses, cancer prevention strategies, and cancer services, updated analyses using more recent GBD data are warranted. Furthermore, the GBD enables a direct comparison of risk–cancer pairs within a consistent global framework and provides standardized attributable fractions that may not be routinely available from national cancer registries. The GBD study’s consistent methodology and regular updates also enable longitudinal analysis over a period stretching back to 1990. While the Australian Burden of Disease studies, which are produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), provide disease burden estimates, they lack global comparability and cover a wide set of risk–cancer pairs.

This study aims to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date assessment of preventable cancer deaths and DALYs lost in the Australian context by quantifying the cancer burden attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors, using data and methodology of the GBD2021 study. The GBD2021 study provides global cancer burden estimates, including incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, and risk factor attributions. We emphasized risk attributable to cancer deaths and DALYs lost, the latter often overlooked in the available evidence. DALYs provide a comprehensive measure of the overall disease burden (both fatal and non-fatal burden), combining years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability [21].

2. Materials and Methods

The GBD2021 study employed a systematic approach to quantify health loss from major diseases, injuries, and risk factors across populations worldwide. The study leveraged a wide array of data sources, including disease registries, vital registration systems, household surveys, hospital records, clinical data, reports, and scientific literature. These data were collated and analyzed using standardized methods. Subsequently, these data underwent rigorous quality control and further standardization processes to ensure their accuracy and comparability. The GBD employed Bayesian meta-regression disease modeling (DisMod-MR 2.1) and causes of death ensemble modeling (CODEm) methods to calculate fatal and non-fatal health metrics over time [22].

The GBD2021 study includes estimates for the global burden of disease due to cancers, including both common and rare malignancies, allowing exploration of the impact of various exposures on cancer burden. Within the GBD database, the relationship between each risk factor and health outcomes can be analyzed to estimate the relative risk of each risk factor on the outcome (e.g., incidence, deaths, or DALYs). The population attributable fraction (PAF), which accounts for the competing risk of death, risk factor interdependence, and statistical uncertainty, is then used to predict the proportion of health risk that could be reduced if exposure to the risk factor is lowered to the minimum level. A detailed description of the GBD study aims, methodology, data sources, and analytic tools has been reported previously [23].

To handle the non-independent, synergistic effects of multiple risk factors (e.g., how diet and obesity together increase cancer burden more than the sum of their individual effects), GBD uses a hierarchical, counterfactual approach [23]. This method attributes the burden sequentially, giving priority to risks that are more causally “upstream,” such as metabolic risks over behavioral ones, and it uses a joint exposure distribution to avoid double-counting the burden. This allows GBD to produce internally consistent estimates of the total attributable burden across all risk factors, ensuring that the total burden attributed to all risks does not exceed 100% of the overall disease burden [23].

For our study on cancer burden attributable to risk factors in Australia in 2021, results were extracted and compiled from the GBD Compare (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/cancer) and Global Health Exchange websites (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/) accessed on 13 January 2025. Our outcomes of interest were cancer deaths and DALYs lost. One DALY represents one year of “healthy life” lost due to illness/disability and/or premature death [21]. From the GBD database, we extracted data for causes identified as “neoplasms”, measurements of “death” and “DALY”, and location specified as “Australia”, with metrics including “number”, “percent”, and “rate”. “Risk factors” included all GBD risk factors (explored at both level 1 to understand the role of the three major GBD risk classifications, and levels 2 and 3 for detailed insights into specific risks). The three GBD level-1 risk categories are behavioral, metabolic, and environmental/occupational risks. Behavioral risks include tobacco (smoking, second-hand smoke and chewing tobacco), dietary risks (diet high in processed meat, diet high in red meat, diet high in sodium, diet low in calcium, diet low in fiber, diet low in fruit, diet low in milk, diet low in vegetables, diet low in whole grains), high alcohol use, drug use, physical inactivity, and unsafe sex. Metabolic risks include high body mass index (BMI) and high fasting plasma glucose. Environmental/occupational risks include occupational carcinogens, particulate matter pollution, and residential radon. Overall, 23 specific cancer types (and all cancers combined) and 27 risks (all risks combined, 3 GBD level-1 risks, 8 GBD level-2 risks, and 15 GBD level-3 risks) were included (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of GBD risks and cancer types included in the attributable cancer burden estimation of Australia in 2021.

A total of 159 risk–cancer combinations were estimated. The list of risk factors at the GBD hierarchy (levels 1, 2, and 3) and risk–cancer combinations is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Possible risk–cancer pairs estimated in the GBD 2021 for Australia.

The attributable risk effect measure was estimated as the proportion of cancer deaths and DALYs that can be attributed to a specific risk factor (e.g., DALYs lost due to cancer attributable to behavioral risk factors). The risk-attributed metrics were computed along with a 95% Uncertainty Interval (UI, calculated as the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile values). The results were summarized as estimated numbers, attributed percentages, and age-standardized rates per million population, and presented by sex (male, female, and both).

3. Results

3.1. Cancer-Related Deaths and DALYs Lost in Australia

In 2021, the estimated total number of cancer deaths in Australia was 54,428 (95% UI: 49,281–57,750). Cancer contributed to almost a third of all deaths in Australia (31.1%) in the same year, with a higher proportion of deaths among males than females (33.8% vs. 27.9%). Cancer DALYs lost overall were estimated to be 1,139,729 years (95% UI: 1,057,124–1,195,026), with males experiencing higher DALYs lost than females (652,347 vs. 487,381 years). Lung cancer was the leading cause of death in both sexes, with a significantly higher proportion in males (6.6%) compared to females (5.0%). Prostate cancer in males (4.8%) and breast cancer in females (4.3%) were the second leading causes of cancer deaths in each sex. Colorectal, liver, and pancreatic cancers also contributed significantly to both deaths and the loss of healthy life years across both sexes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated cancer-related deaths and DALYs lost in Australia in 2021.

3.2. Risk-Attributable Cancer Deaths in Australia

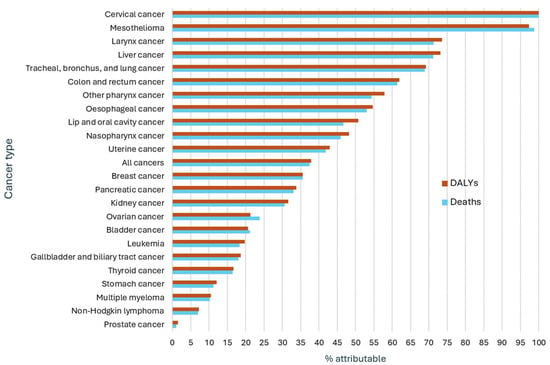

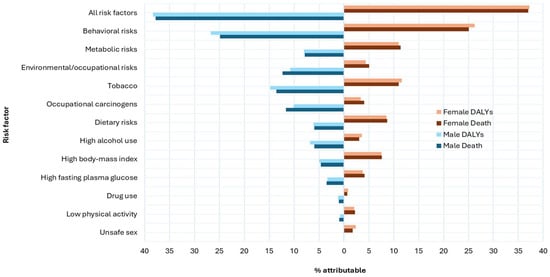

In Australia in 2021, an estimated 20,409 (37.5%) cancer deaths (37.8% in males and 37.0% in females) were attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors. Males had higher risk-attributable cancer death rates compared to females (548.7/million vs. 342.7/million people). Behavioral risks combined (tobacco, dietary risks, high alcohol use, drug use, physical inactivity, and unsafe sex) contributed to 13,600 (25%) cancer deaths, corresponding to 298.4 deaths per million population. Behavioral risks made the greatest contributions to deaths from cancer of the cervix (100%), larynx (63.7%), liver (63.0%), other pharynx (oropharynx and hypopharynx, excluding nasopharynx) (54.4%), esophagus (53.0%), and colorectum (51.6%). Metabolic risks and environmental/occupational risks accounted for 9.4% and 9.3% of cancer deaths (108.2 and 103.1 deaths per million people, respectively). Metabolic risk factors contributed most to deaths from pancreatic (27.0%), kidney (25.8%), liver (21.4%), and colorectal (20.7%) cancers, while environmental/occupational risk factors contributed greatly to mesothelioma (98.8%) and lung cancer (39.1%). Cancer deaths attributed to environmental/occupational risks were higher in males than females (12.3% vs. 5.1%), whereas deaths attributed to metabolic risks were higher in females than males (7.9% vs. 11.4%) (Table 4, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Risk-attributable cancer deaths in Australia in 2021.

Figure 1.

Cancer-related deaths and DALYs lost attributed to all GBD risk factors in Australia in 2021, both sexes.

Figure 2.

All cancer deaths and DALYs lost attributed to selected GBD risk factors in Australia in 2021.

Almost all mesothelioma and cervical cancer deaths were attributed to modifiable risks. Nearly 100% of cervical cancer deaths were attributable to unsafe sex. Across both sexes, larynx (71.3%), liver (71.2%), lung (68.9%), and colorectal (61.5%) cancers also exhibited high-risk-attributable deaths. Risk-attributable death rates were higher in males than females for cancers of the larynx, lip and oral cavity, liver, nasopharyngeal, esophagus, other pharynx, and lung. Stomach cancer, multiple myeloma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma had the lowest proportions of risk factor attributable deaths across both sexes (11.2%, 10.2% and 7.0%, respectively). Only 1.0% of prostate cancer deaths were attributable to modifiable risk factors (Table 4, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Regarding specific risk factors, smoking was the largest contributor to all cancer deaths in both sexes (13.3% in males and 10.8% in females). Approximately 4511 lung cancer deaths in 2021 were attributable to smoking alone, accounting for 44.7% of lung cancer deaths in males. Dietary risks combined accounted for about 39.5% of colorectal cancer deaths in both sexes. Diet low in vegetables accounted for 21.0% esophageal cancer deaths, and a diet low in whole grains accounted for 17.0% of colorectal cancer deaths. Drug use is a highly attributable risk for liver cancer deaths (21.3%). Alcohol use is attributed to 6.0% of all cancer deaths in males, mainly for liver, lip, and oral cavity, and nasopharyngeal cancers. High BMI contributed to 7.6% of all cancer deaths in females, primarily towards uterine and kidney cancers (Table 4, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

3.3. Risk-Attributable Cancer DALYs Lost in Australia

Approximately 431,575 (37.9%) of DALYs lost due to cancer in Australia in 2021 (38.3% in males and 37.2% in females) were attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors. The pattern for cancer DALYs lost attributable to risk factors was similar to patterns observed for risk-attributable cancer deaths. Behavioral, metabolic, and environmental/occupational risks accounted for 302,471 (26.5%), 105,916 (9.3%), and 91,965 (8.1%) of all cancer DALYs lost, respectively. DALYs lost from cervical cancer due to unsafe sex (100%) and from mesothelioma due to occupational carcinogens (97.4%) topped the list. Larynx, liver, lung, and colorectal cancers also had high proportions of risk-attributed DALYs lost (73.6%, 73.2%, 69.2%, and 62.0%, respectively) (Table 5, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 5.

Risk-attributable cancer DALYs lost in Australia in 2021.

Similar to risk-attributable cancer deaths, smoking stands out as the highest contributor to cancer DALYs lost, accounting for 149,615 (13.1%) DALYs lost in Australia in 2021 across both sexes, with a greater contribution in males than females. Smoking-attributable DALYs lost were also high for cancers of the larynx (58.4%), lung (47.9%), other pharynx (29.0%), and esophagus (22.6%). Other notable behavioral risks contributing to high DALYs lost included dietary risks and alcohol use, accounting for 7.1% and 5.4% of all cancer DALYs, respectively. Dietary risks accounted for 39.7% of colorectal cancer DALYs lost, with a diet high in red meat contributing 17.2% and a diet low in whole grains contributing 17.8%. A diet low in vegetables was a significant contributor to DALYs lost in esophageal cancer (20.8%). Alcohol use accounted for 41.6%, 41.2%, and 40.3% of DALYs lost due to nasopharyngeal, other pharynx, and liver cancers, respectively. Occupational carcinogens and high BMI contributed to 82,345 (7.2%) and 69,055 (6.1%) all cancer DALYs lost, respectively. Other notable risk—attributable impacts on DALYs lost included occupational carcinogens with lung cancer (30.7%), high BMI with kidney cancer (26.5%), high fasting plasma glucose with pancreatic cancer (23.6%), drug use with liver cancer (22.4%), and a diet low in vegetables with esophageal cancer (20.8%) (Table 5, Figure 1 and Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study provides an up-to-date examination of cancer burden in Australia attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors. The results highlighted that a significant portion of cancer burden in Australia is preventable through addressing common modifiable risk factors. The novelty of this study lies in its timeliness (using the latest GBD 2021 data), its comprehensiveness (in terms of risk factors and cancer types), its emphasis on DALYs lost for a holistic cancer burden assessment, and its detailed, sex-specific analysis that directly addresses identified limitations in the existing Australian literature. It provides critical, current evidence on the preventable portion of cancer deaths and DALYs, which can inform targeted public health measures and lead to significant public health gains at a population level.

In 2021, cancer was responsible for 31% of all deaths and 17% of healthy life years lost in Australia. Notably, 38% of all cancer deaths and cancer-related DALYs lost were attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors. The results are in line with the 2024 Australian Burden of Disease study, showing 39.9% DALYs of cancer were due to modifiable risk factors [24]. While the Australian Burden of Disease study [24] provides a means to interactively explore broader disease burdens and the risk factors with more recent and ongoing analysis of trends, our study provides comprehensive details of how these risk factors contribute specifically to cancer-related deaths and DALYs lost.

Behavioral risk factors continue to play a critical role in driving the cancer burden in Australia. Our study findings indicate that behavioral risk factors (including tobacco and alcohol use, as well as dietary habits) were major contributors to cancer-related deaths and DALYs lost. Cervical cancer-related deaths and DALYs lost were almost entirely associated with preventable risks: unsafe sexual practices (HPV infection). While Australia’s HPV vaccination program is widely considered successful in reducing cervical cancer, challenges persist in achieving higher vaccine coverage. Key barriers include absenteeism, issues with consent form return, and general vaccine hesitancy [25]. Furthermore, significant disparities in vaccine uptake exist among Indigenous populations due to social, cultural, information, and communication-related barriers [26]. Therefore, implementing measures to enhance the program’s reach and address these specific barriers is crucial for maximizing its impact.

Furthermore, dietary habits and low physical activity significantly contributed to colorectal cancer deaths and DALYs lost. These findings align with results of previous studies, both globally and specific to Australia [1,3,19]. This reflects broader global health patterns, where lifestyle factors are increasingly recognized as key contributors to non-communicable diseases, including cancer [1]. This underscores the considerable potential for cancer prevention through effective strategies that address these risks, such as multi-disciplinary interventions to promote healthy lifestyles and “fat” tax policies [27]. It is also important to view lifestyle and behavioral risks through the lens of the profound influence social, economic, and commercial factors have on shaping health behaviors. For instance, limited access to affordable and healthy food options and the absence of safe and accessible spaces for physical activity are not merely individual choices but rather consequences of broader structural inequities [28]. This implies that targeting only the “behavior” without addressing its social and economic determinants could make it difficult to reduce the risk factors.

Tobacco control measures implemented in Australia over recent decades [29] have resulted in a decline in the smoking-attributable cancer burden [30,31]. The success of these tobacco control measures provides valuable lessons for scaling up and transferring successful public health strategies towards tackling other modifiable risk factors. However, our study and a previous study [32] demonstrated that smoking continues to be the leading single modifiable risk factor for lung cancer and the overall cancer burden. This could reflect the consequences of high smoking rates in the mid-late 1900s to early 2000s, due to relatively long lead times for smoking-related cancers. Furthermore, the reduction in smoking-attributable cancer burden may not be uniform across different population subgroups. For example, tobacco use accounted for 37% of the cancer burden for Indigenous Australians in 2018, while it accounted for 9.2% of the cancer burden in the general population [33]. Another study showed that although smoking-attributable lung cancer has reduced over time, high underlying risk estimates were observed among disadvantaged, remote, and Indigenous female Queenslanders [34]. Smoking rates have also not declined as much in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups as they have in the general population [35], and vaping and tobacco pouches are increasing among younger people [36]. Further targeted smoking cessation strategies are needed specifically targeting these population groups.

Our study shows that excessive alcohol consumption is linked to a high proportion of liver and esophageal cancer deaths and DALYs, while drug use is considerably linked with liver cancer burden. A study conducted in New South Wales, Australia, revealed that for each additional seven alcoholic beverages consumed weekly, the relative risk of mortality from alcohol-related cancers increases by 12%, accounting for 3.4% of all cancer fatalities [37]. These findings underscore the importance of strengthening public health measures aimed at reducing alcohol and drug use. Efforts such as public awareness campaigns, pricing and restricting promotions, and warning labels on alcohol products highlighting the link between alcohol and cancer are needed.

Our analysis suggested that adopting behavior modifications such as a healthy diet, smoking cessation, reduced alcohol consumption, and increased physical activity could have prevented 52% of colorectal cancer deaths and lost DALYs. The importance of interventions targeting multiple risk factors in combination has been previously suggested. A study from Australia highlighted the value of managing multiple risk factors to improve cancer survival in primary care for older individuals, rather than considering individual risk factors in isolation [38]. Promoting physical activity as a component of cancer prevention programs in Australia is also crucial, a finding supported by our study and previous research [8,39,40] showing that physical inactivity contributes to cancer burden. Furthermore, some risk reduction interventions can have a synergistic effect on other cancer prevention efforts, such as screening. For example, a cross-sectional study of 1685 Australian women aged 44–48 and 64–68 years demonstrated that effectively targeting multiple risk factors (current smoking, not working, obesity, anxiety, poor physical health, no children, no partner, receiving income support payments, and low overall health service use) could potentially reduce overall non-participation in cervical cancer screening by 74% [41].

In line with a previous global estimate of cancer burden using GBD2019 data [1], our study indicated that metabolic risk factors (high BMI and high fasting plasma glucose) have seen the largest increases in cancer burden, while behavioral and environmental/occupational risks declined between 2010 and 2021 in Australia (results not reported). Our study also highlighted the strong link between high fasting plasma glucose and pancreatic cancer. Another study showed that high BMI attributed to cancer mortality has increased in the Asia-Pacific region [42]. These trends emphasize the need for continuous monitoring of cancer trends and their association with specific risk factors to inform more targeted prevention efforts. This includes monitoring the potential need to shift investment towards risk reduction and prevention strategies and developing public health campaigns to address these changing risk profiles. In addition to behavioral interventions, addressing obesogenic environments through urban planning (e.g., controlling fast food density), restricting the marketing of junk food in all forms of media (especially to children to reduce patterned behaviors), and providing subsidies for healthy food to low-income families could help.

Our results highlighted notable sex-specific differences in the cancer deaths and DALYs lost attributed to risk factors, with the overall burden being greater for males. Some risk factors also affected one sex more significantly than the other and varied by cancer site. For example, the smoking- and alcohol-attributable burden of lung, liver, and laryngeal cancers was higher in males, while high BMI contributed more to the cancer burden in females. Previous evidence showed that the burden of smoking [7,9,10,16] and alcohol consumption is often higher in men [9], while high BMI contributes to cancer burden slightly more in women [6,10], especially in postmenopausal women [5]. Although some of these disparities may be related to physiological and/or lifestyle differences [43,44], the findings underscore the need to examine cancer control efforts through a gendered lens. Prevention strategies targeting men that challenge social norms have the potential to reduce cancer burden [45].

Our findings show that a substantial portion of the cancer burden (62% of deaths and DALYs lost) was not attributed to any of the GBD risk factors examined, suggesting they may be unavoidable or risk factors that are yet unknown. This implies that merely preventing the reported risk factors would not eliminate all cancer deaths and/or DALYs lost. Instead, a combination of interventions across the cancer control continuum is required, including early detection and timely diagnosis, as well as quality cancer treatment and survivorship care. It is also worth noting that the contribution of modifiable risk factors for some cancers, such as prostate cancer, is small and cannot be controlled merely with primary prevention measures. The Lancet Commission on Prostate Cancer indicates that the rise in prostate cancer cases cannot be entirely mitigated through lifestyle modifications or public health initiatives, as there is a significant genetic risk of prostate cancer [46]. This evidence underscores the importance of considering family history and genetic testing in these cohorts of patients. Public health initiatives promoting screening among high-risk groups, such as providing information and tools for people over 50 to make informed decisions about screening, would also reduce cancer deaths and DALYs.

Finally, social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic disadvantage, education, housing, employment, and access to nutritious food and healthcare, may create the conditions in which health decisions are made, with economically disadvantaged communities often facing limited access to health-promoting resources [28,47,48]. Moreover, structural and commercial determinants—including urban planning, marketing practices by tobacco and alcohol industries, and inequities in healthcare access—create environments of elevated risk for marginalized populations [49]. Equity-focused public health policies and cross-sectoral collaboration are essential for reducing cancer disparities and shifting the focus from individual behavior to systemic drivers of health inequity [50].

This study has some limitations. The GBD study relies on modeling and estimation techniques, which may introduce some uncertainty into the reported findings. The GBD modeling techniques interpolate and extrapolate data where direct measurements are sparse or unavailable. The PAFs are calculated using the modeled exposure data and assumed effect sizes from the literature, which may not perfectly reflect the nuances of a particular local context, such as unique environmental factors, genetic predispositions, or social determinants of health. Therefore, the interpretation of the estimated attributable fractions should be approached cautiously, as they represent a probabilistic estimate rather than an exact causal relationship. This also implies that the GBD statistical estimates do not diminish the value of cancer registries, national health surveys, and well-designed research studies; rather, they can be used to supplement the evidence we can draw from such sources, especially when there is a lack of data. Some known and unknown modifiable risk factors, such as e-cigarette use, UV exposure, infections, and screening uptake, were not included in the GBD estimates, which may lead to an underreporting of the preventable burden of cancer in this study, particularly for some of the less prevalent/less studied cancers. Additionally, the results may not fully capture the complex interplay of multiple risk factors in cancer. Although the GBD modeling techniques address the interactive effects of risk factors (e.g., tobacco and alcohol, diet and obesity) using a hierarchical, counterfactual framework approach, the complexity of biological and social interactions means that this framework is a simplified representation of reality [19]. For example, some interactions may not be fully captured, or the data used to model the exposure-response relationships may have biases or be insufficient. Furthermore, there are no GBD subnational estimates for Australia, and hence, we were unable to further investigate disparities. Australia has a universal public health insurance scheme, Medicare, that funds public hospital care and provides subsidized access to private medical services. Although the system aims to provide all residents with access to high-quality cancer care, cancer outcomes vary across some population groups. Previous evidence shows significant disparities in cancer burden in Indigenous, remote, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and/or people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds [33,34,51,52]. Another limitation when analyzing risk-attributable cancer deaths is that advancements in cancer treatment may have reduced mortality. Notably, data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [53] shows that between 2000 and 2024, the age-adjusted cancer mortality rate in Australia declined from 255 to 194 deaths per 100,000 people, while the age-adjusted cancer incidence rate rose from 582 to 624 cases per 100,000 people. Finally, while melanoma burden attributable to UV exposure was not included in this estimate, Australia has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in the world and UVR exposure is an established risk factor [54]. This is why public health campaigns in Australia, such as the “Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, Slide” campaign, have been so focused on promoting sun protection [55]. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the need for continued efforts to reduce the impact of modifiable risk factors on mortality and healthy life lost due to cancer. The results indicate that initiatives aimed at minimizing exposure to cancer risk factors at the population level would have a substantial impact on reducing the burden of cancer.

5. Conclusions

We provide a comprehensive examination of the contribution of modifiable risk factors to Australia’s cancer burden derived from GBD2021 data, which offers valuable insights for targeting risk reduction and cancer prevention strategies tailored to the Australian context. This study reinforces the need for continued efforts to address modifiable risk factors to reduce cancer burden and reiterates the importance of reliable, comprehensive cancer data in informing policy and practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T., B.D., T.H.H.D.N. and K.B.; methodology, T.T. and K.B.; software, T.T.; validation, T.H.H.D.N. and K.B.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T.; resources, K.B. and D.R.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T. and K.B.; writing—review and editing, B.D., L.M., P.W., T.H.H.D.N., S.B., D.R. and K.B.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, K.B.; project administration, T.T.; funding acquisition, T.T. and K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The GBD study is funded through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. T.T. and K.B. are supported through Cancer Council SA Research Fellowships.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data used in this study are aggregated Australia GBD2021 data and do not contain any personally identifiable information. Ethical approval was not required as the study uses data available in the public domain. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were extracted from the Global Health Exchange website (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/, accessed on 13 January 2025). Further interactive exploration of GBD2021 results on cancer burden can be done here: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/cancer. The GBD data and tools guide can be accessed here: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/about-gbd/gbd-data-and-tools-guide. To view, download, and use GBD results, click here: https://www.healthdata.org/data-tools-practices/interactive-visuals/gbd-results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- GBD 2019 Cancer Risk Factors Collaborators. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Institute NSW. Cancer Risk Factors. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/about-cancer/cancer-basics/cancer-risk-factors (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Hu, J.; Dong, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, R.; Teixeira, W.; He, X.; Ye, D.-W.; Ti, G. Cancer burden attributable to risk factors, 1990–2019: A comparative risk assessment. iScience 2024, 27, 109430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, D.; Gurney, J. Preventing cancer: The only way forward. Lancet 2022, 400, 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, M.E.; Vajdic, C.M.; Canfell, K.; MacInnis, R.J.; Banks, E.; Byles, J.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Taylor, A.W.; Mitchell, P.; Giles, G.G.; et al. The preventable burden of breast cancers for premenopausal and postmenopausal women in Australia: A pooled cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 2383–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, M.E.; Vajdic, C.M.; Canfell, K.; MacInnis, R.; Hull, P.; Magliano, D.J.; Banks, E.; Giles, G.G.; Cumming, R.G.; Byles, J.E.; et al. The burden of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors: The Australian cancer-PAF cohort consortium. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; Arriaga, M.E.; Canfell, K.; MacInnis, R.J.; Byles, J.E.; Banks, E.; Shaw, J.E.; Mitchell, P.; Giles, G.G.; Magliano, D.J.; et al. The preventable burden of endometrial and ovarian cancers in Australia: A pooled cohort study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 153, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; Canfell, K.; MacInnis, R.; Arriaga, M.E.; Banks, E.; Magliano, D.J.; Giles, G.G.; Cumming, R.G.; Byles, J.E.; Mitchell, P.; et al. The future burden of lung cancer attributable to current modifiable behaviours: A pooled study of seven Australian cohorts. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; Canfell, K.; MacInnis, R.J.; Banks, E.; Byles, J.E.; Giles, G.G.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Hirani, V.; Gill, T.K.; et al. The Future Burden of Head and Neck Cancers Attributable to Modifiable Behaviors in Australia: A Pooled Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; MacInnis, R.J.; Canfell, K.; Giles, G.G.; Hull, P.; Shaw, J.E.; Cumming, R.G.; Gill, T.K.; Banks, E.; Mitchell, P.; et al. The future burden of kidney and bladder cancers preventable by behavior modification in Australia: A pooled cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.F.; Sarich, P.E.A.; Vaneckova, P.; Wade, S.; Egger, S.; Ngo, P.; Joshy, G.; Goldsbury, D.E.; Yap, S.; Feletto, E.; et al. Cancer incidence and cancer death in relation to tobacco smoking in a population-based Australian cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 1076–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajdic, C.M.; MacInnis, R.J.; Canfell, K.; Hull, P.; Arriaga, M.E.; Hirani, V.; Cumming, R.G.; Mitchell, P.; Byles, J.E.; Giles, G.G.; et al. The Future Colorectal Cancer Burden Attributable to Modifiable Behaviors: A Pooled Cohort Study. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018, 2, pky033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.N.; Whiteman, D.C.; Webb, P.M.; Neale, R.E.; Reid, A.; Norman, R.; Fritschi, L. The future excess fraction of cancer due to lifestyle factors in Australia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 75, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; MacInnis, R.J.; Canfell, K.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Banks, E.; Giles, G.G.; Byles, J.E.; Gill, T.K.; Mitchell, P.; et al. Thyroid cancers potentially preventable by reducing overweight and obesity in Australia: A pooled cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteman, D.C.; Webb, P.M.; Green, A.C.; Neale, R.E.; Fritschi, L.; Bain, C.J.; Parkin, D.M.; Wilson, L.F.; Olsen, C.M.; Nagle, C.M.; et al. Cancers in Australia in 2010 attributable to modifiable factors: Summary and conclusions. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, M.E.; Vajdic, C.M.; MacInnis, R.J.; Canfell, K.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Byles, J.E.; Giles, G.G.; Taylor, A.W.; Gill, T.K.; et al. The burden of pancreatic cancer in Australia attributable to smoking. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melaku, Y.A.; Appleton, S.L.; Gill, T.K.; Ogbo, F.A.; Buckley, E.; Shi, Z.; Driscoll, T.; Adams, R.; Cowie, B.C.; Fitzmaurice, C. Incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and risk factors of cancer in Australia and comparison with OECD countries, 1990–2015: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 52, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Australia Collaborators. Pre-COVID life expectancy, mortality, and burden of diseases for adults 70 years and older in Australia: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2024, 47, 101092. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Australia Collaborators. The burden and trend of diseases and their risk factors in Australia, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Disease (GBD): Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). 2021. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/about-gbd (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2162–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/australian-burden-of-disease-study-2024/contents/interactive-data-on-risk-factor-burden/changes-in-risk-factors-over-time (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Swift, C.; Dey, A.; Rashid, H.; Clark, K.; Manocha, R.; Brotherton, J.; Beard, F. Stakeholder Perspectives of Australia’s National HPV Vaccination Program. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.E.; Kenzie, L.; Letendre, A.; Bill, L.; Shea-Budgell, M.; Henderson, R.; Barnabe, C.; Guichon, J.R.; Colquhoun, A.; Ganshorn, H.; et al. Barriers and supports for uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination in Indigenous people globally: A systematic review. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisnowski, J.; Street, J.M.; Merlin, T.; Fürnsinn, C. Improving food environments and tackling obesity: A realist systematic review of the policy success of regulatory interventions targeting population nutrition. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrnioti, G.; Eden, C.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Alston, C.; Syrnioti, A.; Newman, L.A. Social Determinants of Cancer Disparities. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8094–8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.S.; Weber, M.; Feletto, E.; Smith, M.A.; Yu, X.Q. Cancer burden and control in Australia: Lessons learnt and challenges remaining. Ann. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Mu, H.; Yu, P.; Deng, C. Changing trends in lung cancer disease burden between China and Australia from 1990 to 2019 and its predictions. Thorac. Cancer 2025, 16, e15430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adair, T.; Hoy, D.; Dettrick, Z.; Lopez, A.D. Tobacco consumption and pancreatic cancer mortality: What can we conclude from historical data in Australia? Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Respiratory Tract Cancers Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of respiratory tract cancers and associated risk factors from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1030–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and National Indiginous Australian Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Peroamnace Framewrok: Tier 1-Health Status and Outcomes: 1.08 Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-08-cancer (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Cramb, S.M.; Baade, P.D.; White, N.M.; Ryan, L.M.; Mengersen, K.L. Inferring lung cancer risk factor patterns through joint Bayesian spatio-temporal analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015, 39, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Insights into Australian Smokers, 2021–2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/insights-australian-smokers-2021-22 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey/contents/summary (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Sarich, P.; Canfell, K.; Egger, S.; Banks, E.; Joshy, G.; Grogan, P.; Weber, M.F. Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns and cause-specific mortality in an Australian cohort of 181,607 participants aged 45 years and over. Public Health 2025, 239, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirani, V.; Naganathan, V.; Blyth, F.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Gnjidic, D.; Stanaway, F.F.; Seibel, M.J.; Waite, L.M.; Handelsman, D.J.; Cumming, R.G. Multiple, but not traditional risk factors predict mortality in older people: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age 2014, 36, 9732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, L.F.; Page, A.N.; Dunn, N.A.; Pandeya, N.; Protani, M.M.; Taylor, R.J. Population attributable risk of modifiable risk factors associated with invasive breast cancer in women aged 45–69 years in Queensland, Australia. Maturitas 2013, 76, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L.; Milne, R.L.; Moore, M.M.; Bigby, K.J.; Sinclair, C.; Brenner, D.R.; Moore, S.C.; Matthews, C.E.; Bassett, J.K.; Lynch, B.M. Estimating cancers attributable to physical inactivity in Australia. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2024, 27, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, S.C.; Butterworth, P.; Jacomb, P.; Tait, R.J. Personal factors influence use of cervical cancer screening services: Epidemiological survey and linked administrative data address the limitations of previous research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, C.L.; Batty, G.D.; Lam, T.H.; Barzi, F.; Fang, X.; Ho, S.C.; Jee, S.H.; Ansary-Moghaddam, A.; Jamrozik, K.; Ueshima, H.; et al. Body-mass index and cancer mortality in the Asia-Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration: Pooled analyses of 424,519 participants. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.B.; McGlynn, K.A.; Devesa, S.S.; Freedman, N.D.; Anderson, W.F. Sex Disparities in Cancer Mortality and Survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdas, P.M.; Cheater, F.; Marshall, P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 49, 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy, M.; Saab, M.M.; Hegarty, J.; Von Wagner, C.; O’mAhony, M.; Murphy, M.; Drummond, F.J. Promoting men’s knowledge of cancer risk reduction: A systematic review of interventions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N’DOw, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: Planning for the surge in cases. Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, S.; Collin, J.; Daube, M.; Depoux, A.; Freudenberg, N.; Gilmore, A.B.; Johns, P.; Laar, A.; Marten, R.; McKee, M.; et al. Commercial determinants of health: Future directions. Lancet 2023, 401, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialon, M. An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy-Nichols, J.; Jones, A.; Buse, K. Taking on the Commercial Determinants of Health at the level of actors, practices and systems. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 981039. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, L.F.; Green, A.C.; Jordan, S.J.; Neale, R.E.; Webb, P.M.; Whiteman, D.C. The proportion of cancers attributable to social deprivation: A population-based analysis of Australian health data. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 67, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW). Cancer Data in Australia. 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia/contents/overview (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Olsen, C.M.; Wilson, L.F.; Green, A.C.; Bain, C.J.; Fritschi, L.; Neale, R.E.; Whiteman, D.C. Cancers in Australia attributable to exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation and prevented by regular sunscreen use. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Council. Skin Cancer Prevention Campaigns: Slip, Slop, Slap, Seek, Slide. Available online: https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/causes-and-prevention/sun-safety/campaigns-and-events/slip-slop-slap-seek-slide (accessed on 21 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).