Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Broadening the Scope of Supportive Care: Early Palliative Care

1.2. Shift from Prognostic to Needs-Based Determination for Referral to Palliative Care

1.3. Agency and Uncertainty

2. Integrating Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care

2.1. Overview

2.2. Component 1: Modern Control Theory: Perspectives on Personal Agency and Uncertainty in Palliative Care

2.3. Component 2: Optimal Matching of Need and Provision of Supportive Care

2.4. Component 3: Dimensions of Hope in the Context of Palliative Care

3. Overview of the New Integrative Theory of Hope

4. Integration of the Components: A Hypothetical Narrative with Implications for Psycho-Social Processes in Palliative Care

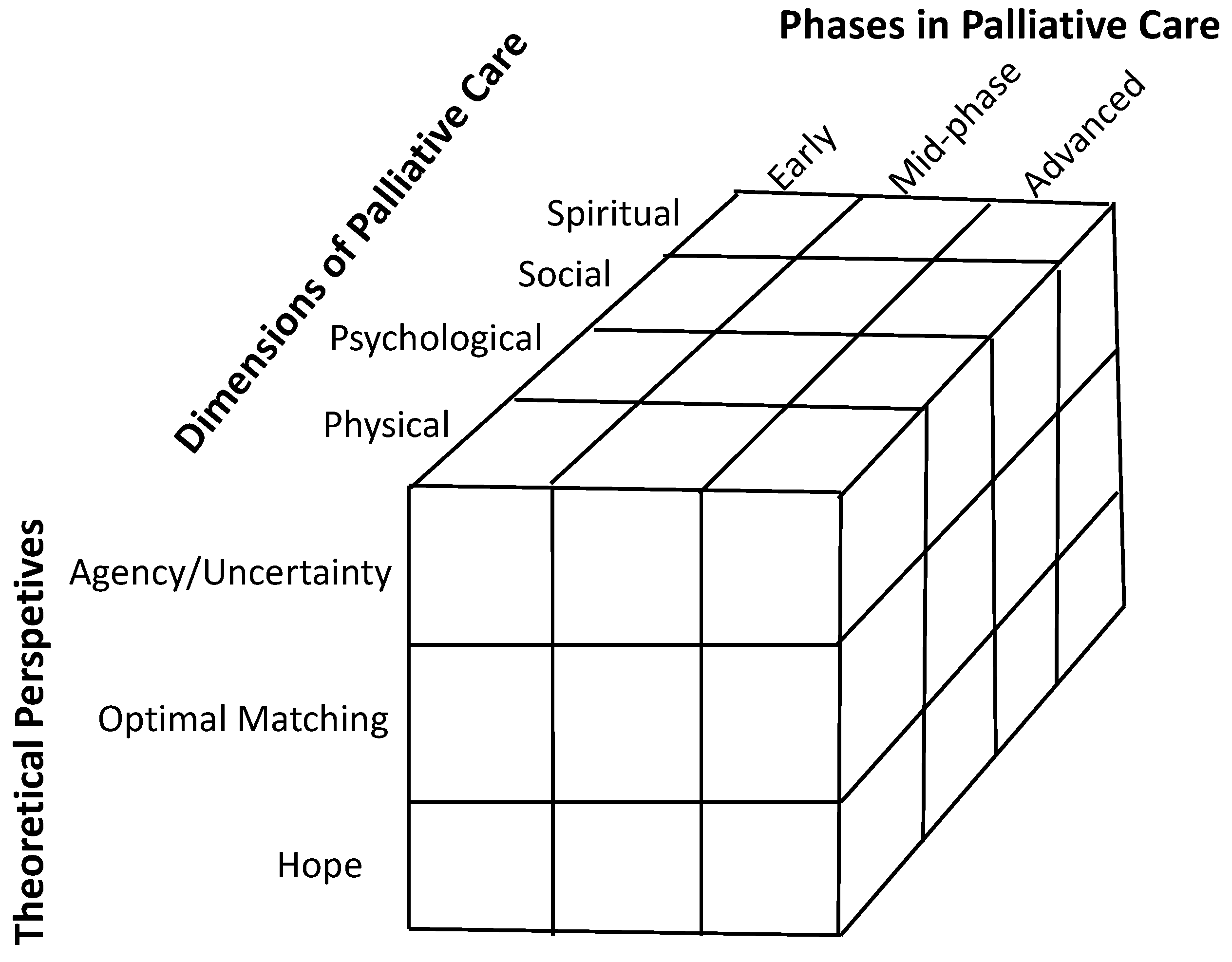

4.1. Integration of Psychosocial Components with Phases of Palliative Care

4.2. Integration of Psychosocial Components with the Dimensions of Palliative Care

5. Future Directions and the Challenge of Health Disparities

5.1. Future Directions

5.2. Health Disparities in Palliative Care

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hui, D.; De La Rosa, A.; Chen, J.; Dibaj, S.; Delgado Guay, M.; Heung, Y.; Liu, D.; Bruera, E. State of palliative care services at US cancer centers: An updated national survey. Cancer 2020, 126, 2013–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 316, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, D.; Tanuseputro, P.; Perez, R.; Pond, G.R.; Seow, H. Early initiation of palliative care is associated with reduced late-life acute-hospital use: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayastha, N.; LeBlanc, T.W. When to integrate palliative care in the trajectory of cancer care. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rücker, G.; Friederich, H.; Villalobos, M.; Thomas, M.; Hartmann, M. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD011129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Sekaran, S.; Kochhar, H.; Khan, A.; Gupta, I.; Mago, A.; Maskey, U.; Marzban, S. Hospice vs palliative care: A comprehensive review for primary care physician. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 4168–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2015, 4, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kissane, D.W.; Watson, M.; Breitbart, W. Psycho-Oncology in Palliative and End of Life Care; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, L.; Riba, M. Psychiatric care in oncology and palliative medicine: New challenges and future perspectives. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 452–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L.B.; Brenner, K.O.; Shalev, D.; Jackson, V.A.; Seaton, M.; Weisblatt, S.; Jacobsen, J.C. To accompany, always: Psychological elements of palliative care for the dying patient. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.; Gründel, M.; Mehnert, A. Psycho-oncology and palliative care: Two concepts that fit into comprehensive cancer care. In Palliative Care in Oncology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, S.; Antunes, B.; Kelly, M.P.; Barclay, S. End-of-life care quality measures: Beyond place of death. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, spcare-003841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolchin, D.W.; Brooks, F.A.; Knowlton, T. The state of palliative care education in United States physical medicine and rehabilitation residency programs. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.K.J.; Klein, W.M.P.; Arora, N. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: A conceptual taxonomy. Med. Decis. Mak. 2011, 31, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Santacroce, S.J.; Chen, D.; Song, L. Illness uncertainty, coping, and quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2020, 29, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.; Sonet, E. Does patient activation level affect the cancer patient journey? Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1276–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuosmanen, L.; Hupli, M.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Haavisto, E. Patient participation in shared decision-making in palliative care—An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 3415–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stajduhar, K.; Funk, L.; Jakobsson, E.; Öhlén, J. A critical analysis of health promotion and ‘empowerment’ in the context of palliative family care-giving. Nurs. Inq. 2010, 17, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.; Thomas, R.; Howell, D.; Dubouloz Wilner, C. Empowering cancer survivors in managing their own health: A paradoxical dynamic process of taking and letting go of control. Qual. Health Res. 2023, 33, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, G.C. Three Philosophical Moralists: Mill, Kant, and Sartre; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sacks, R.; Overton, V.; Parrotta, C.D. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehling, S.; Kissane, D.W. Existential distress in cancer: Alleviating suffering from fundamental loss and change. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 2525–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J. “Letting go”: From ancient to modern perspectives on relinquishing personal control—A theoretical perspective on religion and coping with cancer. J. Relig. Health 2017, 56, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Serpentini, S.; Philip, E.J.; Yang, M.; Salamanca-Balen, N.; Heitzmann Ruhf, C.A.; Catarinella, A. Social relationship coping efficacy: A new construct in understanding social support and close personal relationships in persons with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.; Philip, E.; Yang, M.; Heitzmann, C. Matching of received social support with need for support in adjusting to cancer and cancer survivorship. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelsky, J. Law’s Relations: A relational Theory of Self, Autonomy, and Law; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca-Balen, N.; Merluzzi, T.V. Hope, uncertainty, and control: A theoretical integration in the context of serious illness. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2622–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, D. Fulfilling Your Dreams with the Seven Spiritual Laws of Success; Share Guide: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2001; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B. Growing by letting go: Nonattachment and mindfulness as qualities of advanced psychological development. J. Adult Dev. 2020, 27, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9 Tips to Release Control and Trust the Universe [Internet]. Available online: https://chopra.com/articles/9-tips-to-release-control-and-trust-the-universe (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Salamanca-Balen, N.; Philip, E.J.; Salsman, J.M. “Letting go”—Relinquishing control of illness outcomes to God and quality of life: Meaning/peace as a mediating mechanism in religious coping with cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadot, P. What is Ancient Philosophy? Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, D.; Kumano, H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 18, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Levin, M.E.; Plumb-Vilardaga, J.; Villatte, J.L.; Pistorello, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and contextual behavioral science: Examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T.; et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieng, M.; Butow, P.; Costa, D.S.J.; Morton, R.; Menzies, S.; Mireskandari, S.; Tesson, S.; Mann, G.J.; Cust, A.E.; Kasparian, N.A. Psychoeducational intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence in people at high risk of developing another primary melanoma: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4405–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Balen, N.; Qiu, M.; Merluzzi, T.V. COVID-19 pandemic stress, tolerance of uncertainty and well-being for persons with and without cancer. Psychol. Health 2021, 38, 1402–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, S.A.; Kurita, K.; Taylor-Ford, M.; Agus, D.B.; Gross, M.E.; Meyerowitz, B.E. Intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive complaints, and cancer-related distress in prostate cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutrona, C.; Shaffer, P.; Wesner, K.; Gardner, K. Optimally matching support and perceived spousal sensitivity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E.; Liebig, B.; Schweighoffer, R. Care coordination in palliative home care: Who plays the key role? Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, E.J.; Merluzzi, T.V. Psychosocial issues in post-treatment cancer survivors: Desire for support and challenges in identifying individuals in need. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2016, 34, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Nairn, R.C. Adulthood and aging: Transitions in health and health cognition. In Life-Span Perspectives on Health and Illness; Whitman, T., Merluzzi, T., White, R., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1999; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, N.; Shah, R. Communication about advanced progressive disease, prognosis, and advance care plans. In Psycho-Oncology in Palliative and End of Life Care; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, H.; Applebaum, A.J.; Zaider, T. Carer, partner, and family-centered support. In Psycho-Oncology in Palliative and End of Life Care; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Berendes, D.; Keefe, F.J.; Somers, T.J.; Kothadia, S.M.; Porter, L.S.; Cheavens, J.S. Hope in the context of lung cancer: Relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 40, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, J.P.C.; da Silva, A.G.; Soares, I.A.; Ashmawi, H.A.; Vieira, J.E. Resilience and hope during advanced disease: A pilot study with metastatic colorectal cancer patients. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A.; Irving, L.M.; Sigmon, S.T.; Yoshinobu, L.; Gibb, J.; Langelle, C.; Harney, P. The will and the ways. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herth, K. Development and refinement of an instrument to measure hope. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1991, 5, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, A.; Arnold, R.M.; Schenker, Y. Holding hope for patients with serious illness. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2021, 326, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.L.; Miller, V.; Walter, J.K.; Carroll, K.W.; Morrison, W.E.; Munson, D.A.; Kang, T.I.; Hinds, P.S.; Feudtner, C. Regoaling: A conceptual model of how parents of children with serious illness change medical care goals. BMC Palliat. Care 2014, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Vachon, D.O.; Heitzmann, C.A. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: The critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliat. Support. Care 2011, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellehear, A. Spirituality and palliative care: A model of needs. Palliat. Med. 2000, 14, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnecke, E.; Salvador Comino, M.R.; Kocol, D.; Hosters, B.; Wiesweg, M.; Bauer, S.; Welt, A.; Heinzelmann, A.; Müller, S.; Schuler, M.; et al. Electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) improve the assessment of underrated physical and psychological symptom burden among oncological inpatients. Cancers 2023, 15, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipp, H.; Haasenritter, J.; Hach, M.; Becker, D.; Schütze, D.; Engler, J.; Bösner, S.; Kuss, K. State-wide implementation of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in specialized outpatient palliative care teams (ELSAH): A mixed-methods evaluation and implications for their sustainable use. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J. Racial/Ethnic Minority Patients May Be Less Likely Than White Patients to Receive Palliative Care during Breast Cancer Treatment; American Association for Cancer Research Online Newsletter: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Initial Phase and Goals | Mid-Level Phase and Goals | Advanced Phase and Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agency—Uncertainty |

|

|

|

| Optimal Matching: Patient–Provider–Carer |

|

|

|

| Hope |

|

|

|

| Control | Low | Q3. Hope vested in Transcendence Outcomes uncertain, vested in others, external forces medical science, God, the Universe Letting go, adaptive, disengagement, trust | Q4. Hope vested in Acceptance Outcomes certain, controlled by others, external forces Acceptance, benefit finding, meaning making, disengagement, denial, despair |

| High | Q2. Hope vested in Endurance Outcomes uncertain but vested in persistent, personal effort Endurance, resilience, exhaustion | Q1. Hope vested in Self-Efficacy Outcomes vested in agency, prior successes in similar situations Self-efficacy, confidence | |

| Uncertainty | |||

| High | Low | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merluzzi, T.V.; Salamanca-Balen, N.; Philip, E.J.; Salsman, J.M.; Chirico, A. Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care. Cancers 2024, 16, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020342

Merluzzi TV, Salamanca-Balen N, Philip EJ, Salsman JM, Chirico A. Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care. Cancers. 2024; 16(2):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020342

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerluzzi, Thomas V., Natalia Salamanca-Balen, Errol J. Philip, John M. Salsman, and Andrea Chirico. 2024. "Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care" Cancers 16, no. 2: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020342

APA StyleMerluzzi, T. V., Salamanca-Balen, N., Philip, E. J., Salsman, J. M., & Chirico, A. (2024). Integration of Psychosocial Theory into Palliative Care: Implications for Care Planning and Early Palliative Care. Cancers, 16(2), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020342