Psycho-Educational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Advanced Patients and Their Caregivers: Lessons Learned from a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

- to evaluate the QoL, caregiver burden, and physical performance;

- to evaluate the acceptability of the intervention among dyads.

2.2. Participants and Setting

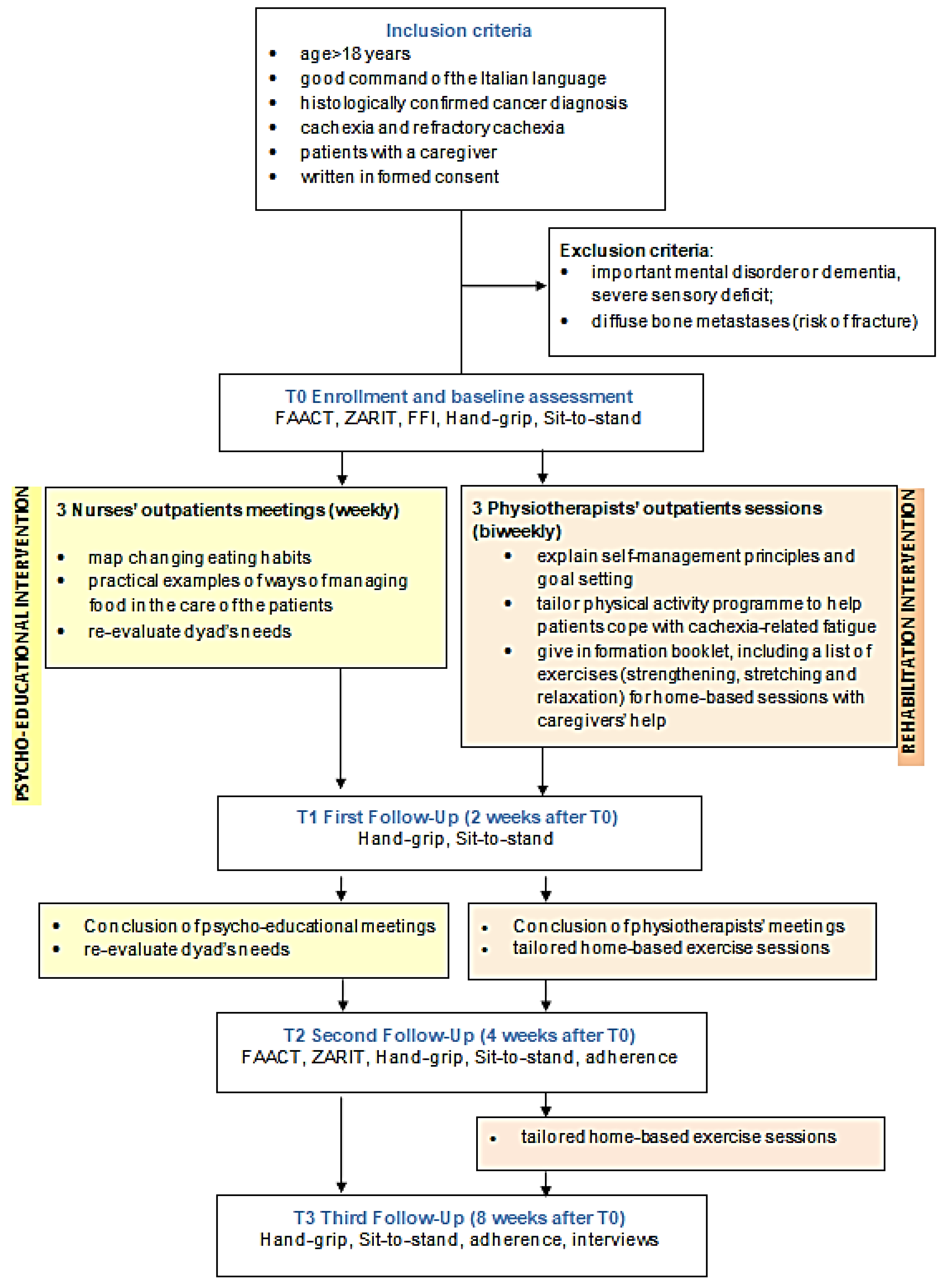

2.3. Intervention

2.4. The Psycho-Educational Intervention

2.5. The Rehabilitative Component

2.6. Outcomes

- patient upper limb physical performance was measured by a hand-grip strength test [33],

- patient lower limb physical performance was measured by a 30 s sit-to-stand test [34],

- the acceptability of the intervention among dyads—patients and caregivers—was evaluated by ad hoc, semi-structured interviews carried out by external researchers. The FAACT and Zarit Burden Scale were self-reported questionnaires, while the hand-grip strength test and the 30-s sit-to-stand test were assessed by physiotherapists, according to the standardized scale recommendations. These evaluations aimed to collect descriptive data to establish the power calculations required for a future full-scale study. Qualitative secondary aims included the exploration of the acceptability, perceived benefits, concerns, strengths, and weaknesses of the intervention from the point of view of interviewed dyads and healthcare professionals (HPs) (see File S2). Ad hoc, semi-structured interviews of the dyads were conducted one month after the intervention by an external research medical doctor (GFM) with formal training and six years of experience in qualitative research in PC and by the principal investigator (LB) of the study. Both researchers did not take part in the delivery of the intervention; the participants did not know them before the interviews, and the intervention was announced by the recruiters (PC professionals during ordinary care).

2.7. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

2.8. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Data

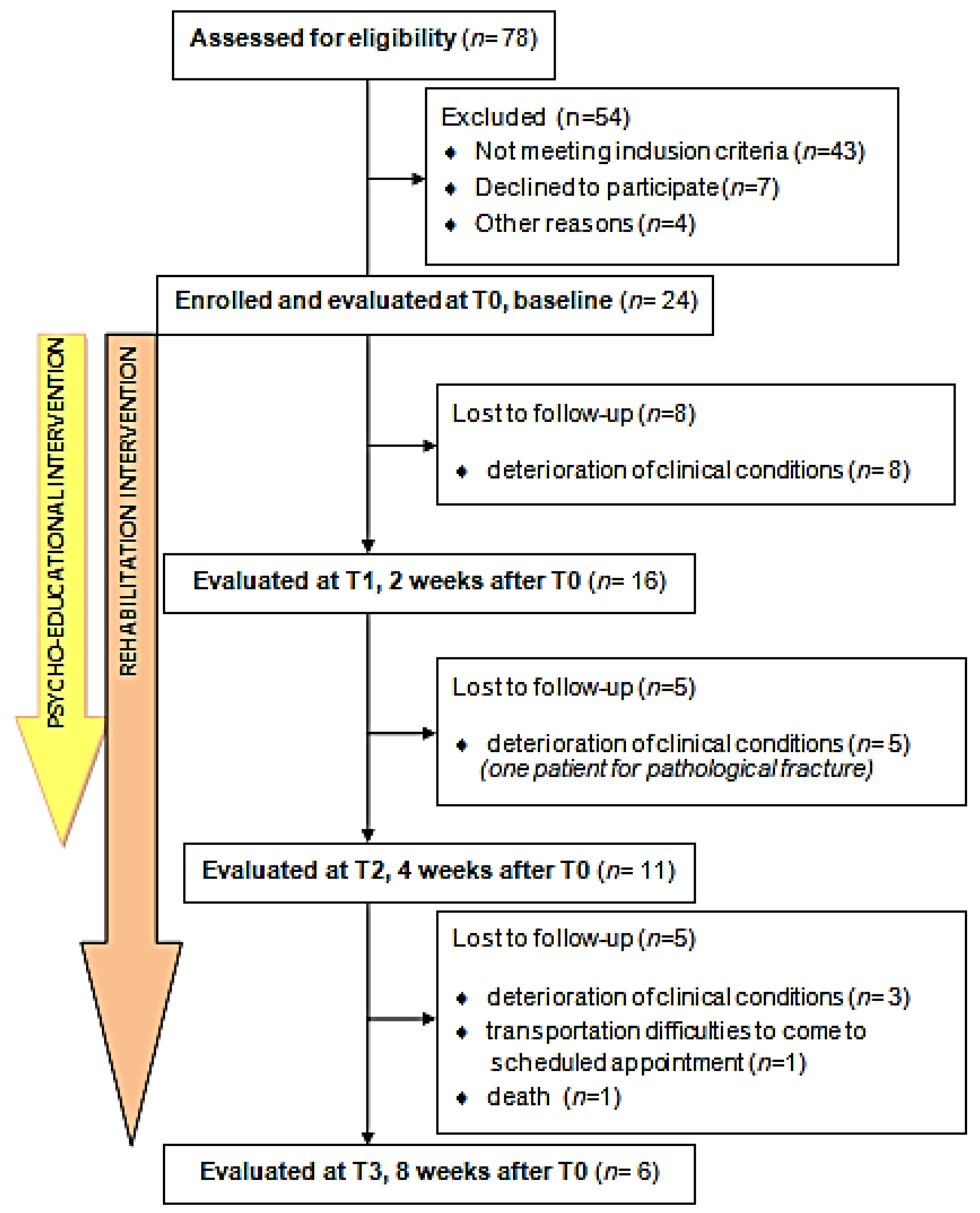

3.2. Feasibility Data

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.4. Qualitative Analysis

3.4.1. Bimodal Intervention

3.4.2. Psycho-Educational Intervention

3.4.3. Physiotherapist Intervention

3.4.4. Inter-Professional Collaboration

3.4.5. Dyad as the Intervention’s Target

3.4.6. Suggestions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearon, K.; Arends, J.; Baracos, V. Understanding the Mechanisms and Treatment Options in Cancer Cachexia. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Strasser, F.; Gonella, S.; Solheim, T.S.; Madeddu, C.; Ravasco, P.; Buonaccorso, L.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Baldwin, C.; Chasen, M.; et al. Cancer Cachexia in Adult Patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines(☆). ESMO Open. 2021, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition—A Consensus Report from the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and Classification of Cancer Cachexia: An International Consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddocks, M.; Hopkinson, J.; Conibear, J.; Reeves, A.; Shaw, C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Practical Multimodal Care for Cancer Cachexia. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 10, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, E.; Hui, D. Palliative Care Research: Lessons Learned by Our Team over the Last 25 Years. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J. Struggling with Nutrition in Patients with Advanced Cancer: Nutrition and Nourishment-Focusing on Metabolism and Supportive Care. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. S2), ii27–ii34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, C.; Cramer, A.; Kestenbaum, A.; Durazo, C.; Downey, A.; Russell, M.; Geluz, J.; Ma, J.D.; Roeland, E.J. Evidence-Based Palliative Care Approaches to Non-Pain Physical Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 34, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Dev, R.; Bruera, E. The Last Days of Life: Symptom Burden and Impact on Nutrition and Hydration in Cancer Patients. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 9, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Murton, A.J.; Wilcock, A. Therapeutic Exercise in Cancer Cachexia. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2012, 17, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Jones, L.W.; Wilcock, A. Immunological and Hormonal Effects of Exercise: Implications for Cancer Cachexia. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 7, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, A.J.; Silva, V.; Sawaris Neto, L.; Teixeira Basmage, J.P.; Peccin, M.S.; Maddocks, M. Exercise for Cancer Cachexia in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD010804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheville, A.L.; Girardi, J.; Clark, M.M.; Rummans, T.A.; Pittelkow, T.; Brown, P.; Hanson, J.; Atherton, P.; Johnson, M.E.; Sloan, J.A.; et al. Therapeutic Exercise during Outpatient Radiation Therapy for Advanced Cancer: Feasibility and Impact on Physical Well-Being. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 89, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberholzer, R.; Hopkinson, J.B.; Baumann, K.; Omlin, A.; Kaasa, S.; Fearon, K.C.; Strasser, F. Psychosocial Effects of Cancer Cachexia: A Systematic Literature Search and Qualitative Analysis. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2013, 46, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.; McKenna, H.; Fitzsimons, D.; McCance, T. The Experience of Cancer Cachexia: A Qualitative Study of Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Family Members. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B. Psychosocial Impact of Cancer Cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B. The Emotional Aspects of Cancer Anorexia. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2010, 4, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, F.; Binswanger, J.; Cerny, T.; Kesselring, A. Fighting a Losing Battle: Eating-Related Distress of Men with Advanced Cancer and Their Female Partners. A Mixed-Methods Study. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.; McKenna, H.; Fitzsimons, D.; McCance, T. Fighting over Food: Patient and Family Understanding of Cancer Cachexia. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2009, 36, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Maeda, I.; Morita, T.; Okajima, Y.; Hama, T.; Aoyama, M.; Kizawa, Y.; Tsuneto, S.; Shima, Y.; Miyashita, M. Eating-Related Distress and Need for Nutritional Support of Families of Advanced Cancer Patients: A Nationwide Survey of Bereaved Family Members. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B. The Psychosocial Components of Multimodal Interventions Offered to People with Cancer Cachexia: A Scoping Review. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 8, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertocchi, E.; Frigo, F.; Buonaccorso, L.; Bassi, M.C.; Venturelli, F.; Tanzi, S. Cancer Cachexia: A Scoping Review on Non-Pharmacological Interventions. EAPC Online Congress, Oral Communication, Abstract ID: OA03:04, 2022.

- Buonaccorso, L.; Bertocchi, E.; Autelitano, C.; Allisen Accogli, M.; Denti, M.; Fugazzaro, S.; Martucci, G.; Costi, S.; Tanzi, S. Psychoeducational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Patients and Their Caregivers: Protocol for a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e042883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Guaitoli, P.R.; Jansma, E.P.; de Vet, H.C.W. Nutrition screening tools: Does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, M.; Apolone, G.; Tanzi, S.; Falco, F.; Rondini, E.; Guberti, M.; Fanello, S.; Cavuto, S.; Savoldi, L.; Piro, R.; et al. Early Integration of Palliative Care Feasible and Acceptable for Advanced Respiratory and Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients? A Phase 2 Mixed-Methods Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Zaider, T.I.; Li, Y.; Hichenberg, S.; Schuler, T.; Lederberg, M.; Lavelle, L.; Loeb, R.; Del Gaudio, F. Randomized Controlled Trial of Family Therapy in Advanced Cancer Continued Into Bereavement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margola, D.; Fenaroli, V.; Sorgente, A.; Lanz, M.; Costa, G. The Family Relationships Index (FRI): Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis in an Italian Community Sample. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 35, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, J.M.; Cella, D.; Hahn, E.A.; Lloyd, S.R.; Tchekmedyian, N.S.; Von Roenn, J.; Leslie, W.T. Re-Validation and Shortening of the Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) Questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. 2000, 9, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, W.; Carrara, R.; Danford, L.; Logemann, J.A.; Cella, D. Quality of Life and Nutrition in the Patient With Cancer. Integr. Nutr. Your Cancer Program 2002, 17, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattat, R.; Cortesi, V.; Izzicupo, F.; Del Re, M.L.; Sgarbi, C.; Fabbo, A.; Bergonzini, E. The Italian Version of the Zarit Burden Interview: A Validation Study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/hand-held-dynamometer-grip-strength (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Available online: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/30-second-sit-stand-test (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Renjith, V.; Yesodharan, R.; Noronha, J.A.; Ladd, E.; George, A. Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grote, M.; Maihöfer, C.; Weigl, M.; Davies-Knorr, P.; Belka, C. Progressive Resistance Training in Cachectic Head and Neck Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Feasibility Trial. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillon, M. Patients with advanced-stage cancer may benefit from telerehabilitation. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Meth 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Fenlon, D.R.; Foster, C.L. Outcomes of a Nurse-Delivered Psychosocial Intervention for Weight- and Eating-Related Distress in Family Carers of Patients with Advanced Cancer. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2013, 19, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Fenlon, D.R.; Okamoto, I.; Wright, D.N.M.; Scott, I.; Addington-Hall, J.M.; Foster, C. The Deliverability, Acceptability, and Perceived Effect of the Macmillan Approach to Weight Loss and Eating Difficulties: A Phase II, Cluster-Randomized, Exploratory Trial of a Psychosocial Intervention for Weight- and Eating-Related Distress in People with Advanced Cancer. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2010, 40, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Richardson, A. A Mixed-Methods Qualitative Research Study to Develop a Complex Intervention for Weight Loss and Anorexia in Advanced Cancer: The Family Approach to Weight and Eating. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatematsu, N.; Naito, T.; Okayama, T.; Tsuji, T.; Iwamura, A.; Tanuma, A.; Mitsunaga, S.; Miura, S.; Omae, K.; Mori, K.; et al. Development of Home-Based Resistance Training for Older Patients with Advanced Cancer: The Exercise Component of the Nutrition and Exercise Treatment for Advanced Cancer Program. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 952–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiskemann, J.; Clauss, D.; Tjaden, C.; Hackert, T.; Schneider, L.; Ulrich, C.M.; Steindorf, K. Progressive Resistance Training to Impact Physical Fitness and Body Weight in Pancreatic Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pancreas 2019, 48, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltoni, M.; Nanni, O.; Pirovano, M.; Scarpi, E.; Indelli, M.; Martini, C.; Monti, M.; Arnoldi, E.; Piva, L.; Ravaioli, A.; et al. Successful validation of the palliative prognostic score in terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 1999, 17, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, K.H.; Courneya, K.S.; Matthews, C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Galvão, D.A.; Pinto, B.M.; Irwin, M.L.; Wolin, K.Y.; Segal, R.J.; Lucia, A.; et al. American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2010, 42, 1409–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Variables | N = 24 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean, years (±SD) | 65.96 (±10.61) |

| Sex | M (n,%) | 15 (62.5%) |

| F (n,%) | 9 (37.5%) | |

| Education | P Primary school (n,%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Secondary school (n,%) | 6 (28.6%) | |

| High school (n,%) | 11 (55.4%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree (n,%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| Occupation | Employed (n,%) | 9 (37.5%) |

| Retired (n,%) | 13 (54.2%) | |

| Other (n,%) | 2 (8.4%) | |

| Family unit | Live alone (n,%) | 2 (8.4%) |

| Live with others (n,%) | 22 (91.7%) | |

| Diagnosis | Pancreatic cancer (n,%) | 6 (25.0%) |

| Lung cancer (n,%) | 5 (20.8%) | |

| Renal cancer (n,%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| Upper GI cancer (n,%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| Bladder cancer (n,%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| Other (n,%) | 5 (20.8%) | |

| Time from diagnosis at enrollment | Years, mean (±SD) | 2.42 (±4.90) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | 70 (n,%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| 80 (n,%) | 13 (56.5%) | |

| 90 (n,%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Cachexia | Reversible (n,%) | 20 (83.3%) |

| Refractory cachexia (n,%) | 4 (16.7%) | |

| Body Mass Index | Usual value, mean (±SD) | 26.68 (±4.74) |

| Current value, mean (±SD) | 22.12 (±4.41) | |

| Weight loss | Usual value, mean kg (±SD) | 79.17 (±18.11) |

| Current value, mean kg (±SD) | 66.00 (±15.80) | |

| Withdrawals from the study | Deterioration of clinical conditions (n, %) | 16 (66.7%) |

| Death (n, %) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Difficulties to come to follow-up (transportation) (n,%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| N of patients dead within 3 months from enrollment | (n,%) | 12 (50.0%) |

| Treatment | Compliant (N out of 24) | Percentage (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Psycho-educational | 20 | 83.3 (62.6–95.3) |

| Rehabilitation | 6 | 25.0 (9.8–46.7) |

| Overall | 6 | 25.0 (9.8–46.7) |

| Assessment | T0 Mean (±SD) | T1 Mean (±SD) | T2 Mean (±SD) | T3 Mean (±SD) | Difference T2–T0 Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAACT score (patients QoL) | (n = 24) 18.42 (± 5.81) | (n = 6) 15.17 (± 2.93) | (n = 6) 1.00 (± 4.94) | ||

| ZARIT score (caregivers burden) | (n = 24) 24.08 (± 12.95) | (n = 6) 18.33 (± 9.44) | (n = 6) 0.50 (± 6.47) | ||

| Hand-grip (patients upper limbs performance) | (n = 23) 23.96 (± 9.57) | (n = 16) 23.16 (± 7.12) | (n = 10) 24.44 (± 7.67) | (n = 5) 20.69 (± 10.57) | (n = 10) −0.37 (± 2.53) |

| Sit-to-stand (N of repetition in 30 s) (patients lower limbs performance) | (n = 23) 8.13 (± 3.66) | (n = 14) 7.79 (± 2.39) | (n = 10) 7.90 (± 4.82) | (n = 5) 9.80 (± 2.28) | (n = 10) −0.70 (± 3.06) |

| Assessment | T0 Mean (±SD) | T1 Mean (±SD) | T2 Mean (±SD) | T3 Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAACT score (patients QoL) | (n = 6) 15.50 (± 4.32) | (n = 6) 15.17 (± 2.93) | ||

| ZARIT score (caregivers burden) | (n = 6) 17.83 (± 13.26) | (n = 4) 17.50 (± 11.96) | ||

| Hand-grip (patients upper limbs performance) | (n = 6) 21.90 (± 8.77) | (n = 6) 21.97 (± 6.99) | (n = 6) 21.29 (± 8.50) | (n = 5) 20.69 (± 10.57) |

| Sit-to-stand (N of repetition in 30 s) (patients lower limbs performance) | (n = 6) 9.17 (± 1.47) | (n = 6) 8.50 (± 1.05) | (n = 6) 9.50 (± 2.51) | (n = 5) 9.80 (± 2.28) |

| Stages or Aspects of the Intervention | Dyads (Patient + Caregiver) N = 6 | HPs (3 PC Nurse + 2 PT) N = 5 |

|---|---|---|

| Bimodal intervention |

“We wanted to help our father with food, so we were very happy” (D3, caregiver)

“My physician told me about the project, then my husband also came and we talked about it together, because I was afraid to weigh on my husband. She helped us” (D2, patient)

“I thought that there was research and that I agreed, at least every patient if he confesses his pain can favor others. I agreed from the beginning. Helping the community” (D3, patient)

“It was not challenging with the therapies, because the nursed changed the days according to the therapies, I’m really good, there has never been a problem” (D2, patient) |

“If you have a high number of patients, it might be possible to schedule fixed timetables for this kind of patients” (FG, I3, nurse)

“Having periodic meetings helped (…) as they have a different point of view (…) and might have a deeper knowledge of the patients” (FG, I2, physiotherapist) “In some cases we had the chance to exchange opinions on patients and caregivers more, and this made a difference” (FG, I3, nurse) |

| Psychoeducational intervention |

“Certain things that were negative to me, I realized that in the conditions in which she was, they were not” (D2, caregiver) “It was the first time we talked so thoroughly about food. Before we talked about it in a medical way, but this intervention is not everywhere, it is not an aspect to be underestimated” (D3, caregiver) Appreciation of the information about CC (booklet) “I didn’t even know what cachexia was” (D2, patient) “I even went to the dictionary to look, otherwise you remain ignorant” (D2, caregiver) “Having instructions on what not to do to facilitate the work of clinicians was fundamental. So knowing what to do so as not to ruin a path is very important” (D3, caregiver) “Have personalized information, because maybe you hear someone who has had the same experience but tells you wrong things; you feel abandoned, even talking about it right away, it’s important” (D5, caregiver) Positive impact on the relationship about food that continues over time “Many times we do not eat the same things; I continue to cook for him, while I had to change my diet, so we make two different menus. But it doesn’t bother us” (D1, patient) “At the beginning you stayed a bit like that, what is it for… it’s a new thing, but with the passage of time it has helped us a lot actually” (D2, caregiver) “I continued to follow the advice they gave me, it was very useful, even after, and I kept talking about it with my daughter. She still asks me ‘Did you do this exercise’” (D4, patient) Positive perception of the nursing role within PC “We already knew the nurse, so we were pleased that she was all inside PC (D3) “She told us that some things she would talk about it with the physician, pleased us we felt followed” (D5, caregiver) |

“We had to explain more times that we weren’t dieticians, and clarify the real objectives of the meetings” (FG, I4, nurse)

|

| PT intervention |

“I tried to adapt based on how I was, the pain, how I felt, as the PT told me” (D3, patient) “It is something that serves, it is the right thing that helps him not to lose calories, we always do the exercises according to the days” (D3, caregiver) “She explained to me the various reasons why I have to do the exercises. The various exercises he gave me he told me to do even more, and I did them, but without getting tired” (D4, patient)

“These last few weeks, I gave up gymnastics because I already had so many problems” (D2, patient) |

|

| Inter-professional collaboration | No specific difficulties perceived |

“Better understanding of (…) patient comprehension of their disease helped our intervention” (…) (FG, I1, physiotherapist) “They (the nurses delivering the psychosocial intervention) might have a better understanding of their hopes, and periodic meetings helped us treating them accordingly” (FG, I1, physiotherapist)” |

| Dyad as the intervention’s target |

“For my daughter it was useful to see how they helped me in eating and doing the exercises, seeing me engaged” (D4, patient) | - Family members were often motivated and encouraging to patients “Facing some difficult topics with the presence of a family member often was helpful for the patient. Caregivers were often the ones who made more questions” (FG, I2, physiotherapist) “On some problems [the caregivers] helped us (…) to understand some problems that were emerging during the day and which could be the right strategies to better cope with them” (FG, I4, nurse) |

| Suggestions |

"Make groups for example on how to cook, do them together as they do for example in other centers” (D5, patient) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buonaccorso, L.; Fugazzaro, S.; Autelitano, C.; Bertocchi, E.; Accogli, M.A.; Denti, M.; Costi, S.; Martucci, G.; Braglia, L.; Bassi, M.C.; et al. Psycho-Educational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Advanced Patients and Their Caregivers: Lessons Learned from a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. Cancers 2023, 15, 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072063

Buonaccorso L, Fugazzaro S, Autelitano C, Bertocchi E, Accogli MA, Denti M, Costi S, Martucci G, Braglia L, Bassi MC, et al. Psycho-Educational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Advanced Patients and Their Caregivers: Lessons Learned from a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. Cancers. 2023; 15(7):2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072063

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuonaccorso, Loredana, Stefania Fugazzaro, Cristina Autelitano, Elisabetta Bertocchi, Monia Allisen Accogli, Monica Denti, Stefania Costi, Gianfranco Martucci, Luca Braglia, Maria Chiara Bassi, and et al. 2023. "Psycho-Educational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Advanced Patients and Their Caregivers: Lessons Learned from a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial" Cancers 15, no. 7: 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072063

APA StyleBuonaccorso, L., Fugazzaro, S., Autelitano, C., Bertocchi, E., Accogli, M. A., Denti, M., Costi, S., Martucci, G., Braglia, L., Bassi, M. C., & Tanzi, S. (2023). Psycho-Educational and Rehabilitative Intervention to Manage Cancer Cachexia (PRICC) for Advanced Patients and Their Caregivers: Lessons Learned from a Single-Arm Feasibility Trial. Cancers, 15(7), 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072063