Mobility of Carriers in Strong Inversion Layers Associated with Threshold Voltage for Gated Transistors

Abstract

1. Introduction

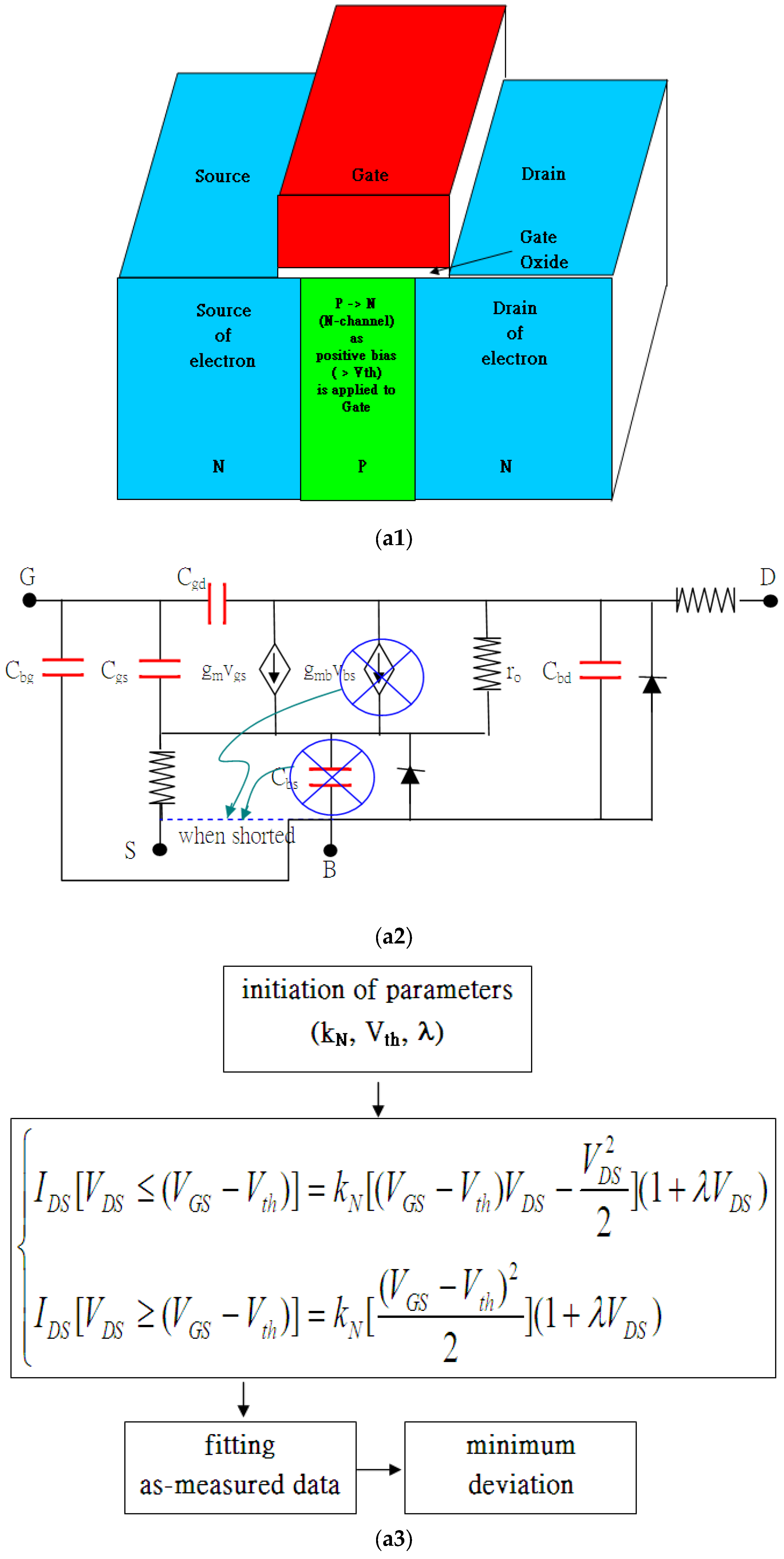

1.1. Modified Conventional Formula and Model

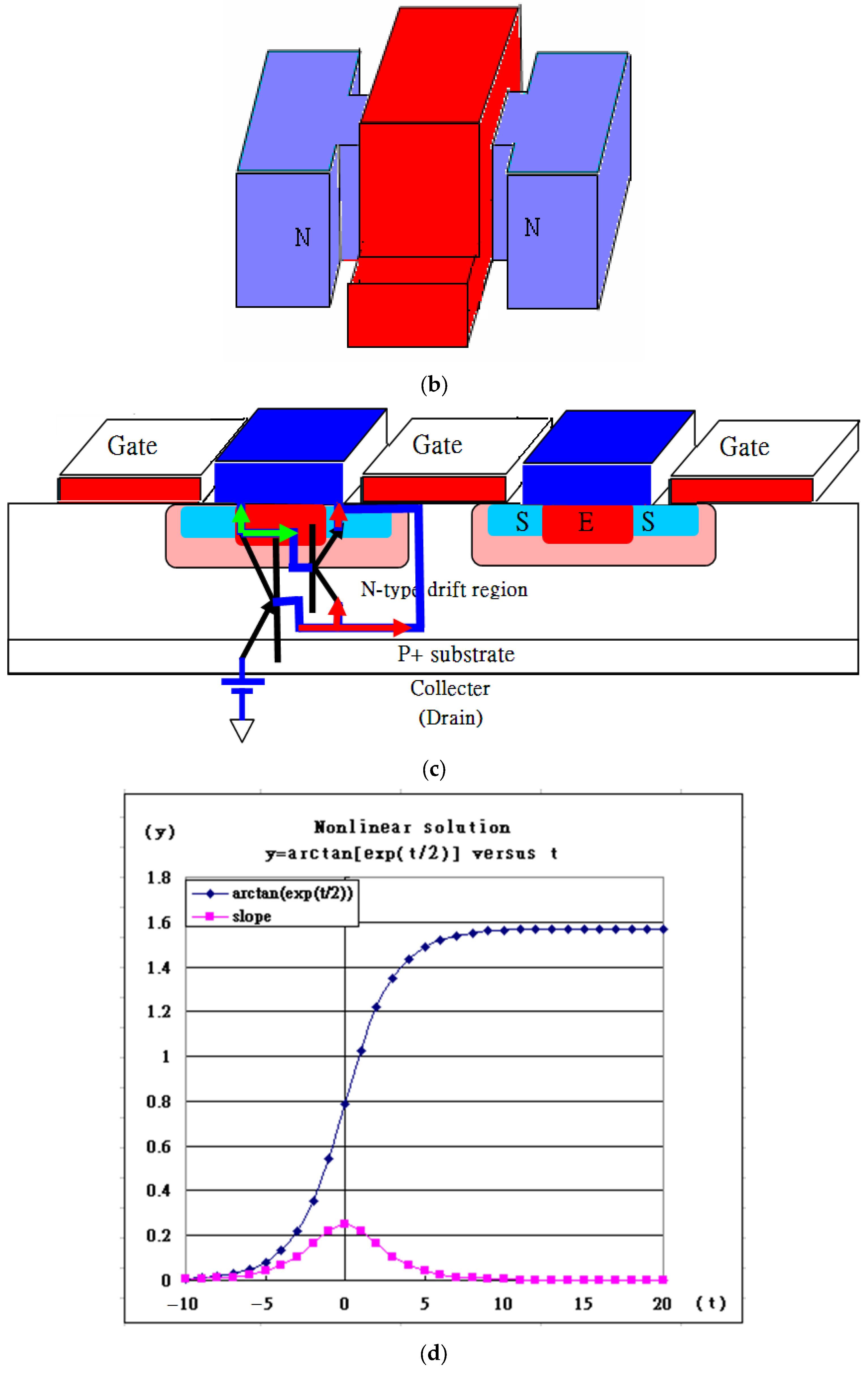

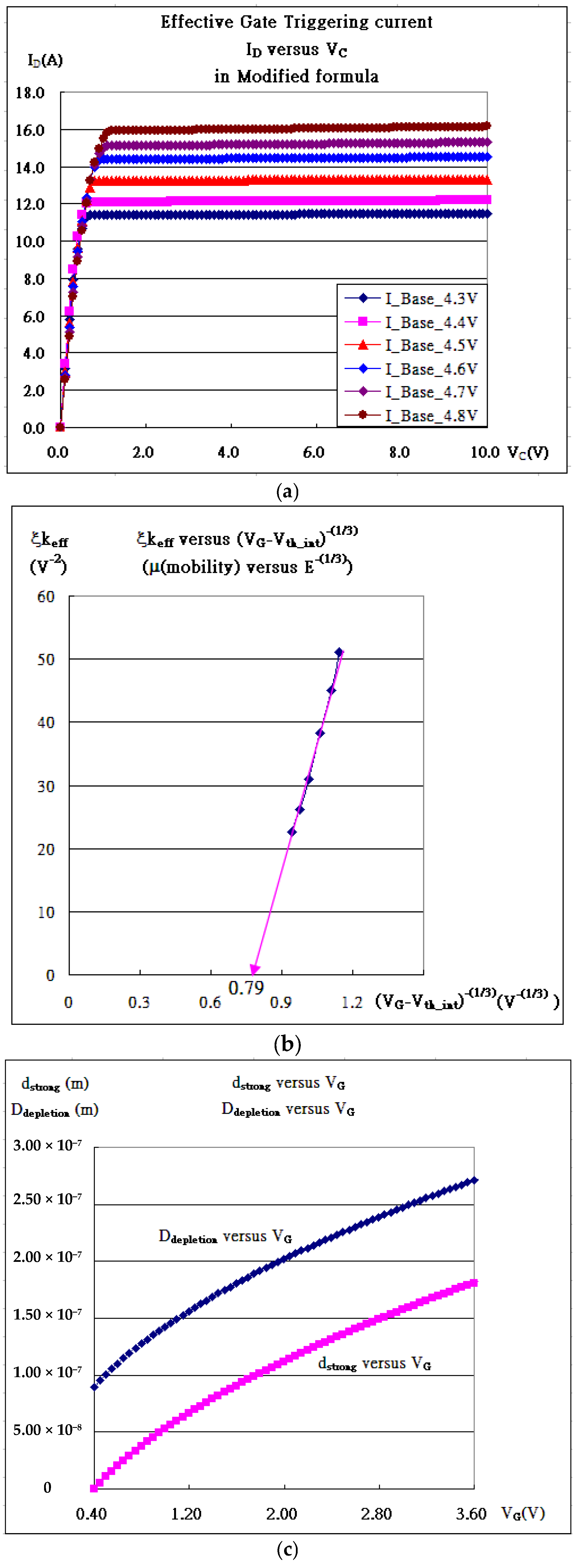

1.2. Isolated Gate Bipolar Transistor

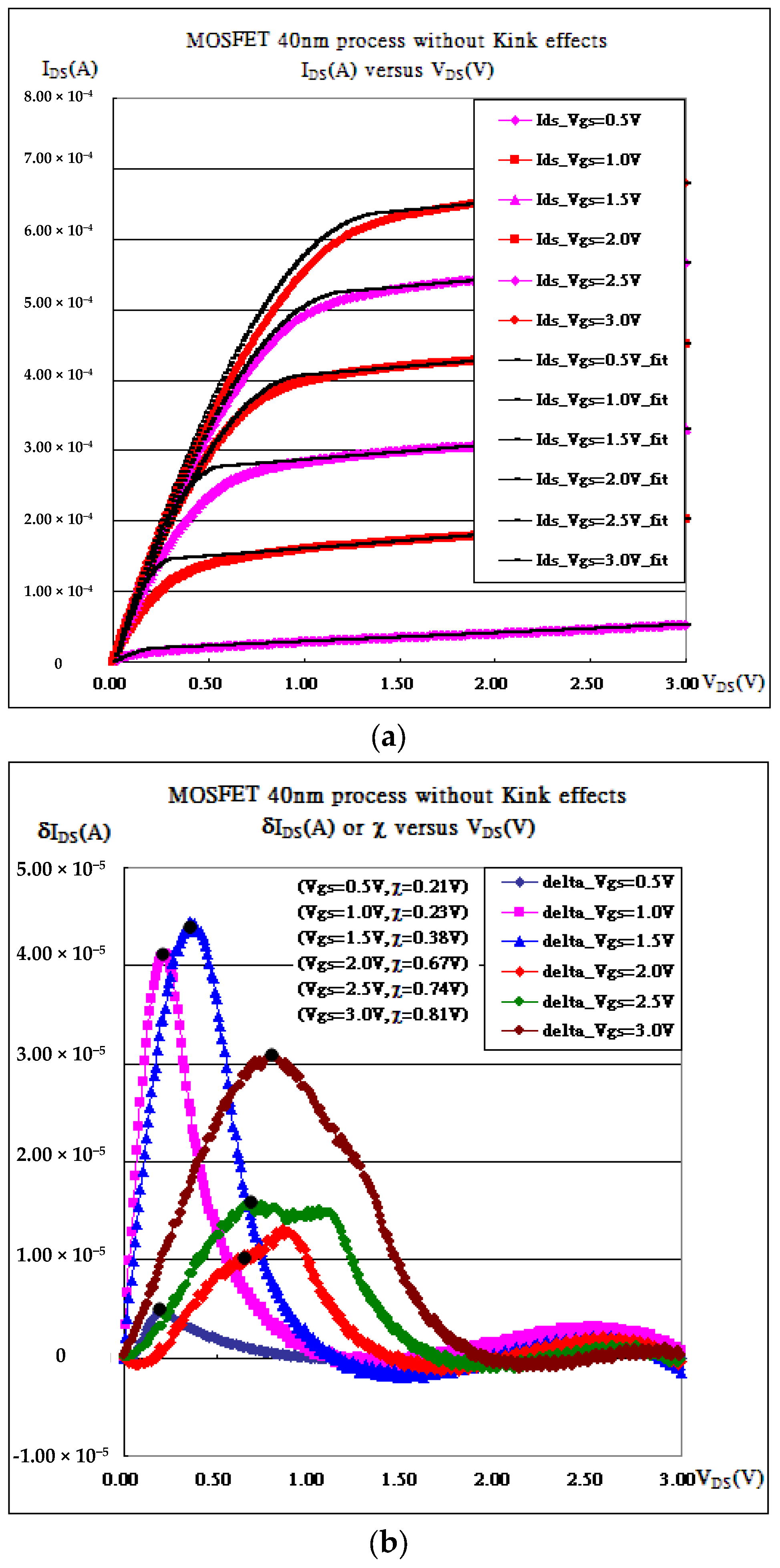

1.3. Kink Effect

1.4. Various Possibilities of Kinks

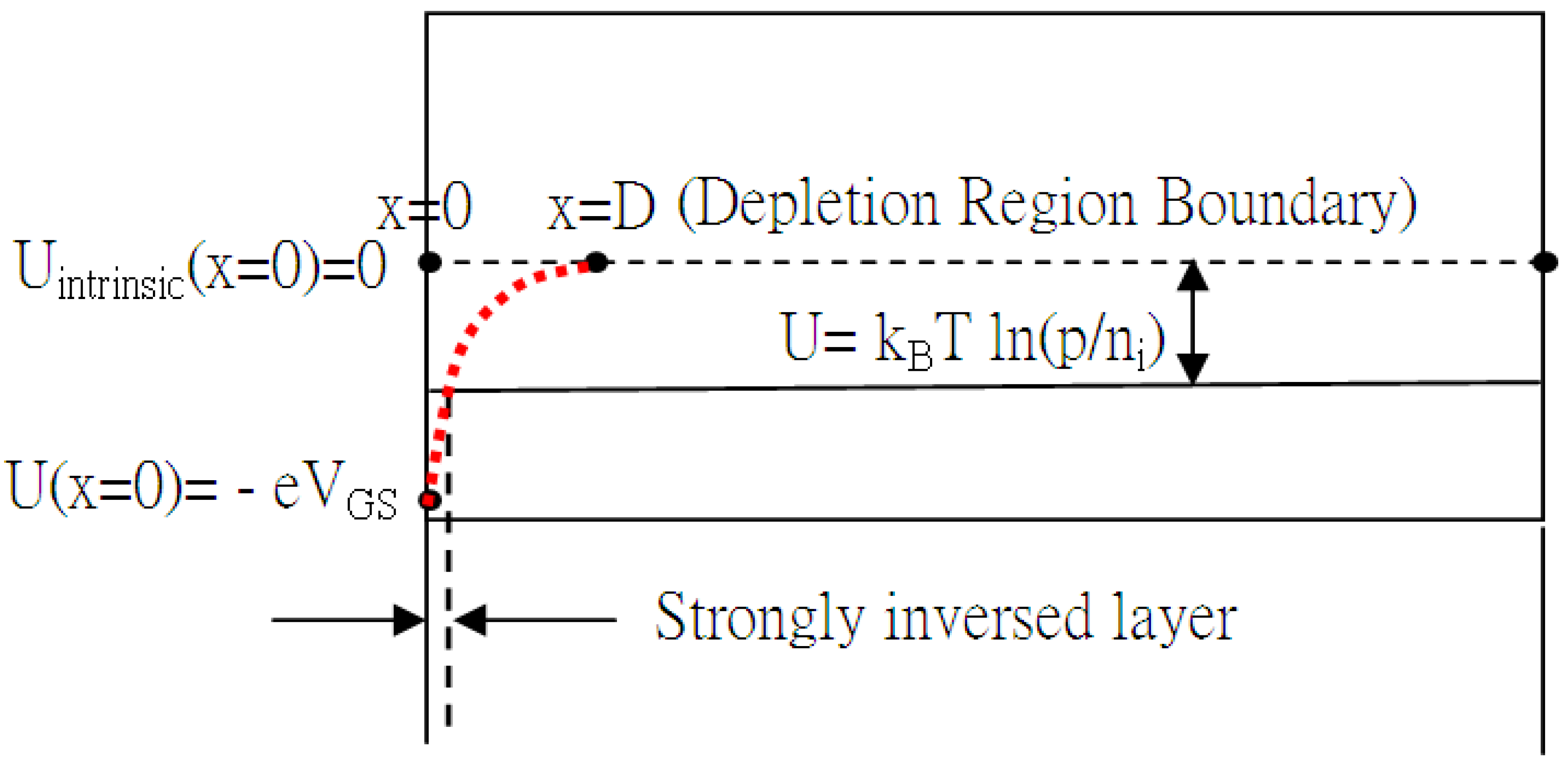

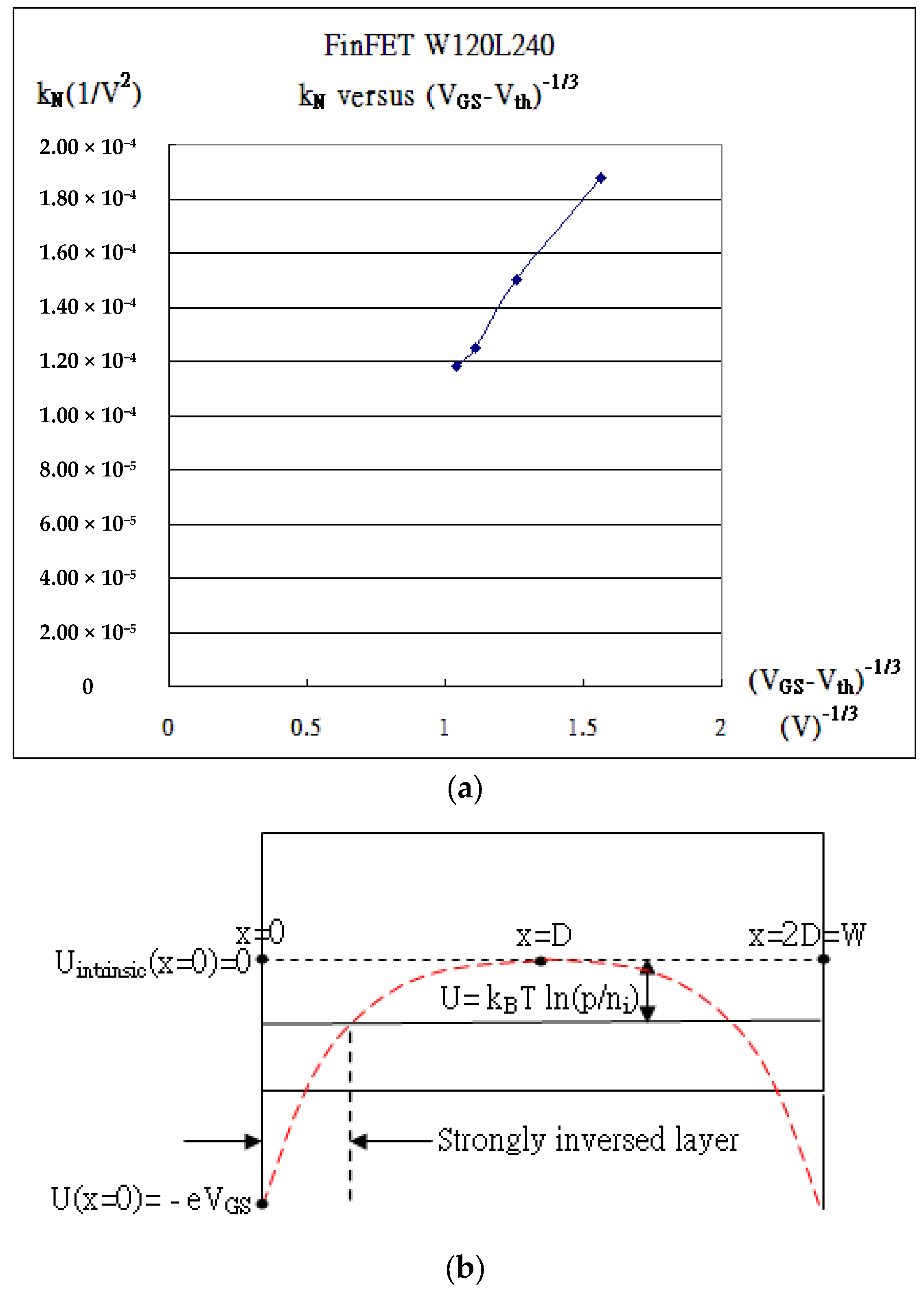

2. Threshold Voltage and the Strong Inversion Layer

3. Current–Voltage Formulas Associated with Threshold Voltage

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, H.-C.; Chi, S.-C. Conclusive Model-Fit Current–Voltage Characteristic Curves with Kink Effects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, G.; Raffo, A.; Vadalà, V.; Vannini, G.; Caddemi, A. A New Study on the Temperature and Bias Dependence of the Kink Effects in S22 and h21 for the GaN HEMT Technology. Electronics 2018, 7, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, B.J. Fundamentals of Power Semiconductor Devices; Current Gain; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Chapter 7.4; pp. 533–563. ISBN 9780387473147. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, P.; Fu, G.; Zhang, D. Modeling Inductive Switching Characteristics of High-Speed Buffer Layer IGBT. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 3075–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, J. Physics-Based Trench-Gate Field-Stop IGBT Modeling With Optimization-Based Parameter Extraction for Device Parameters. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2021, 68, 6305–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Iannuzzo, F.; Blaabjerg, F. A New Lumped-Charge Modeling Method for Power Semiconductor Devices. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 3989–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, G. A Novel Lumped-Charge Model for Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor Based on Dynamic Charge Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 9717–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, A.R., Jr. Analytical modeling of device-circuit interactions for the power insulated gate bipolar transistor (IGBT). In Proceedings of the 1988 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2–7 October 1988; Volume 1, pp. 606–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, R.; Hoffmann, K. An analytical model of IGBTs with low emitter efficiency. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), Monterey, CA, USA, 18–20 May 1993; pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ammous, A.; Ammous, K.; Morel, H.; Allard, B.; Bergogne, D.; Sellami, F.; Chante, J. Electrothermal modeling of IGBTs: Application to short-circuit conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2000, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesh, M.; Yok, S.; Naot, T.; Wataru, S. High Accurate IGBT/IEGT Compact Modeling for Prediction of Power Efficiency and EMI Noise. In Proceedings of the 2019 31st International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), Shanghai, China, 19–23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Tsukamoto, N. High Accurate Representation of Turn-on Switching Characteristics by New IGBT and FWD Compact Models for High Power Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 32nd International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), Vienna, Austria, 13–18 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tone, A.; Miyaoku, Y.; Miura-Mattausch, M.; Kikuchihara, H.; Feldmann, U.; Saito, T.; Mizoguchi, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Mattausch, H.J. HiSIM_IGBT2: Modeling of the Dynamically Varying Balance Between MOSFET and BJT Contributions During Switching Operations. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, Y. Improved Parameterization Methodology for a Field-Stop Trench-Gate IGBT Physical Model by Switching Feature Partitioning. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 3983–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.A.; Claudio, A.; Cotorogea, M.; González, L.H.; Aguayo, J. Reconfigurable Special Test Circuit of physics-based IGBT models parameter extraction. Solid-State Electron. 2010, 54, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibante, R.; Araújo, A.; Carvalho, A. Finite-Element Modeling and Optimization-Based Parameter Extraction Algorithm for NPT-IGBTs. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Takahashi, T.; Suzuki, K.; Tarutani, M. The second-generation 600V RC-IGBT with optimized FWD. In Proceedings of the 28th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), Prague, Czech Republic, 12–16 June 2016; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.; Caiafa, A.; Santi, E.; Hudgins, J.; Palmer, P. Characterization and modeling of high-voltage field-stop igbts. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2003, 39, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, L.H. The sine-Gordon kink. In Quantum Field Theory; The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1985; p. 402. ISBN 0-521-23764-5. [Google Scholar]

- David, J.; Jackson, B. Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley, & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975; p. 654. ISBN 0-471-43132-X. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.-C.; Chi, S.-C.; Yang, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.-T. A Conclusive Algorithm with Kink Effects for Fitting 3-D FinFET and Planar MOSFET Characteristic Curves. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeghbroeck, B. Priciples of Semiconductor Devices, Chapter 7.6 Advanced MOSFET Issues. Available online: https://truenano.com/PSD20/chapter7/ch7_6.htm (accessed on 1 May 2023).

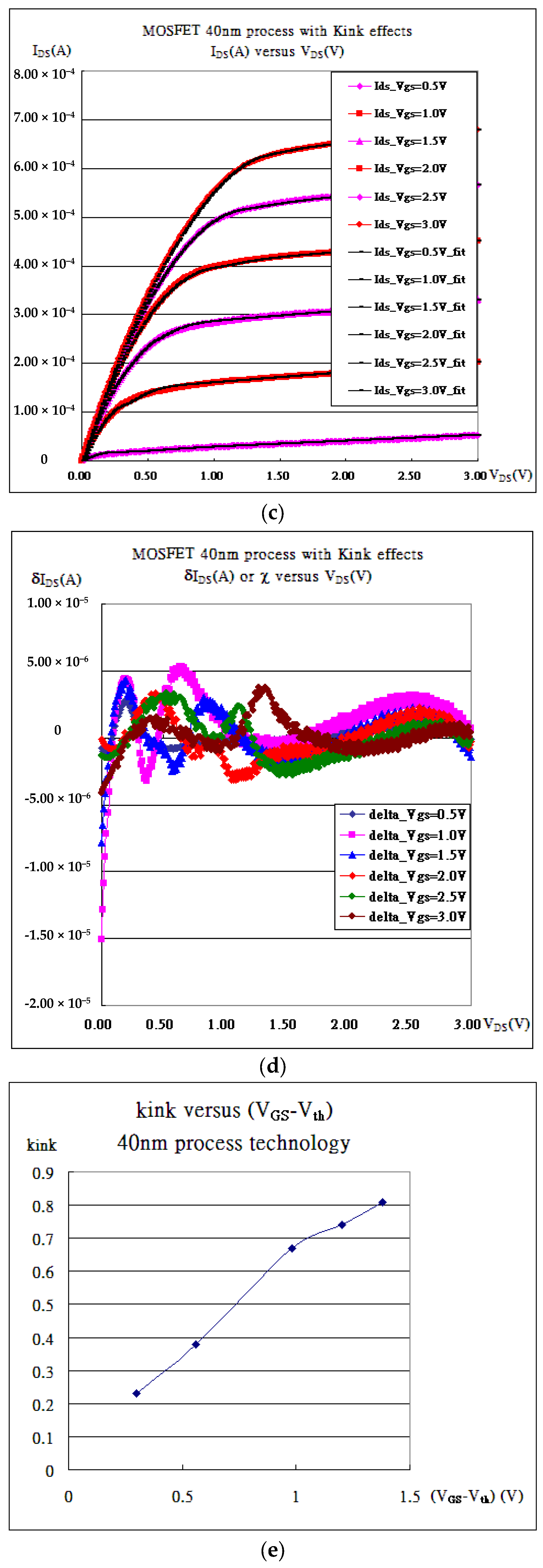

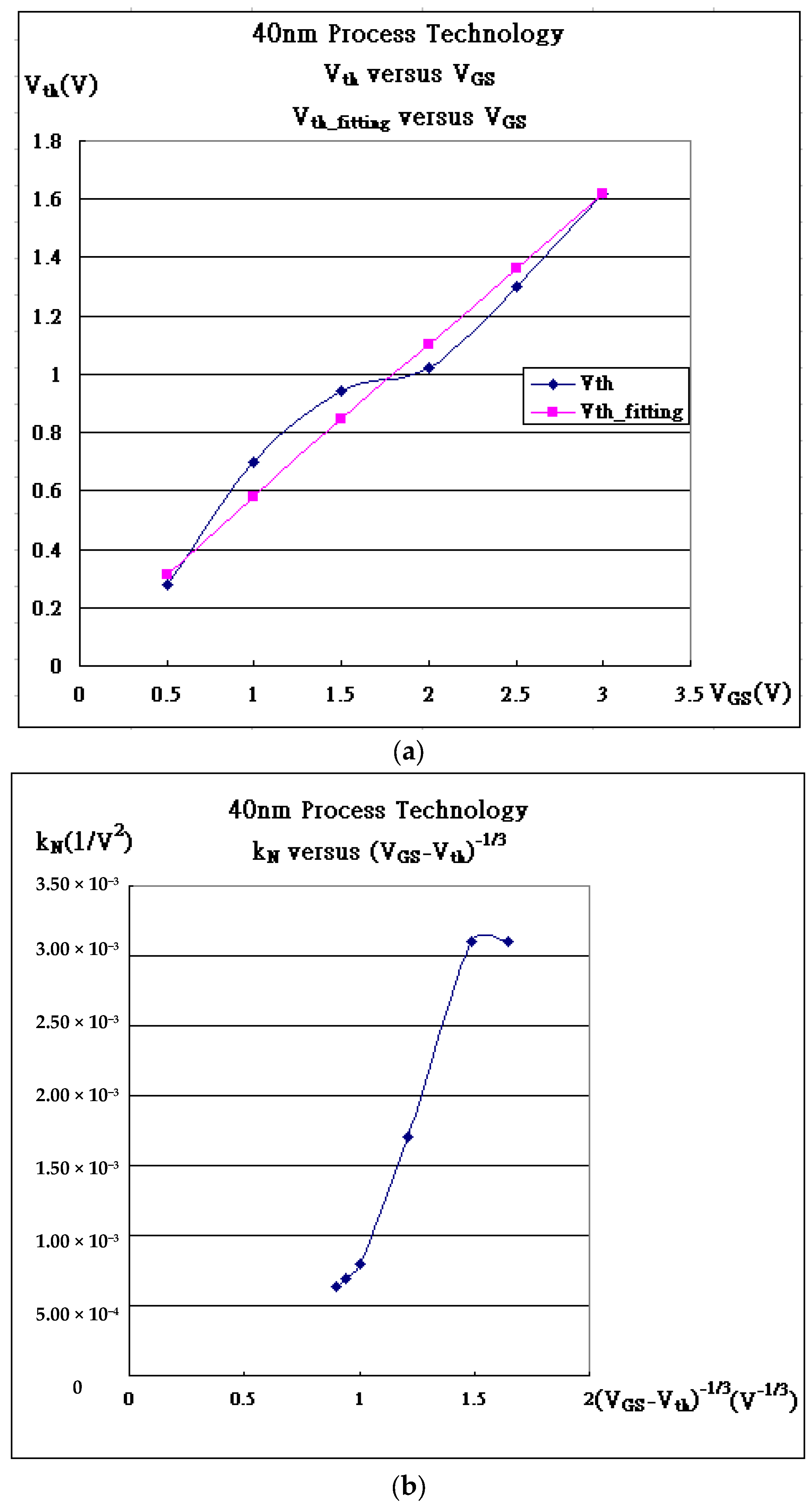

| Gate Bias(V) | kN (A/V2) | Vth_fit (V) | λ (1/V) | Kink (VDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGS = 0.50 V | 6.50 × 10−4 | 0.28 | 0.738 | 0.21 |

| VGS = 1.00 V | 3.10 × 10−3 | 0.70 | 0.151 | 0.23 |

| VGS = 1.50 V | 1.70 × 10−3 | 0.94 | 0.083 | 0.38 |

| VGS = 2.00 V | 8.00 × 10−4 | 1.02 | 0.059 | 0.67 |

| VGS = 2.50 V | 6.90 × 10−4 | 1.30 | 0.047 | 0.74 |

| VGS = 3.00 V | 6.30 × 10−4 | 1.62 | 0.043 | 0.81 |

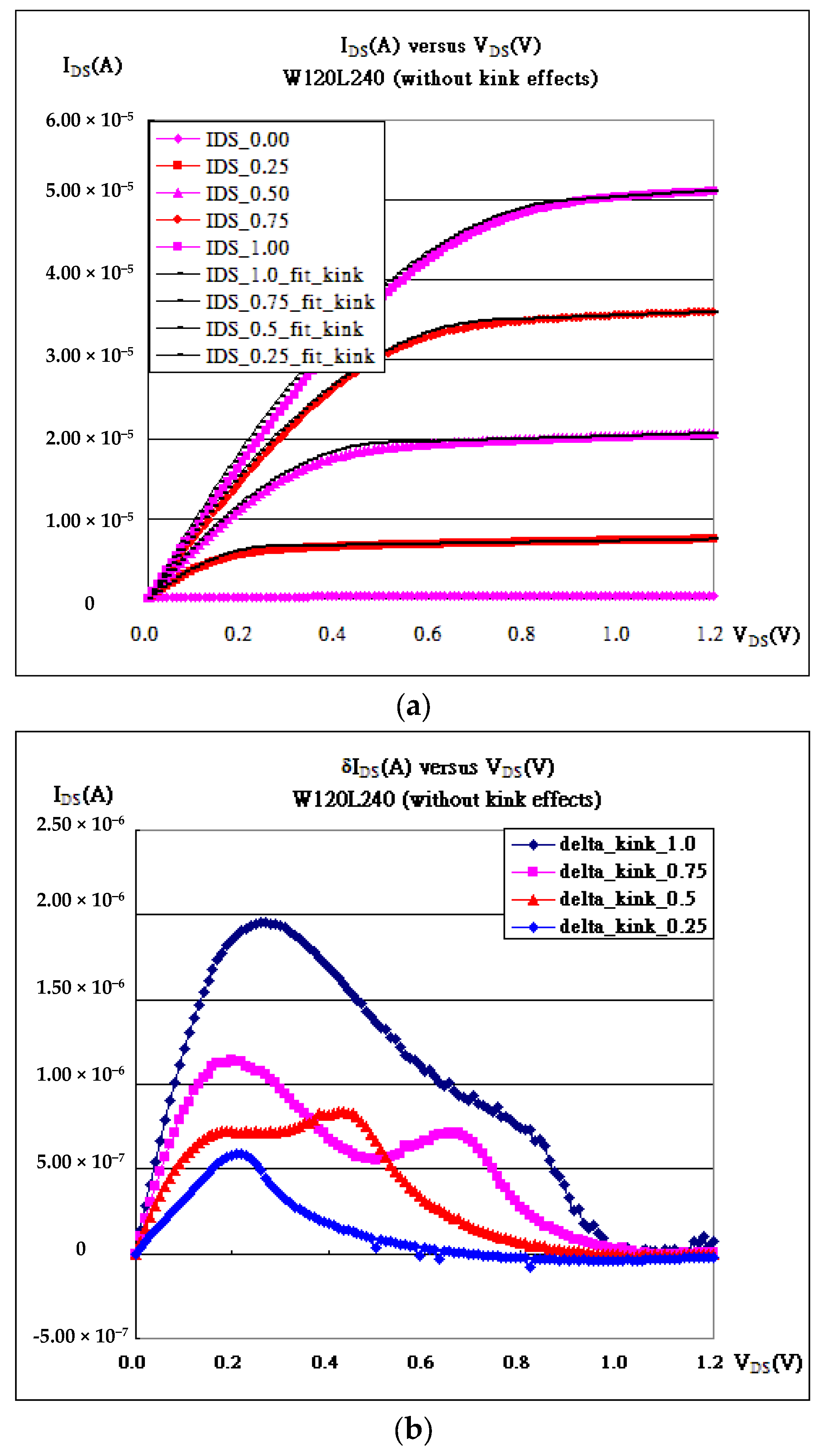

| Gate Bias (V) | kN (A/V2) | Vth_fit (V) | λ (1/V) | Kink (VDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGS = 0.25 V | 1.88 × 10−4 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| VGS = 0.50 V | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| VGS = 0.75 V | 1.25 × 10−4 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| VGS = 1.00 V | 1.18 × 10−4 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.53 |

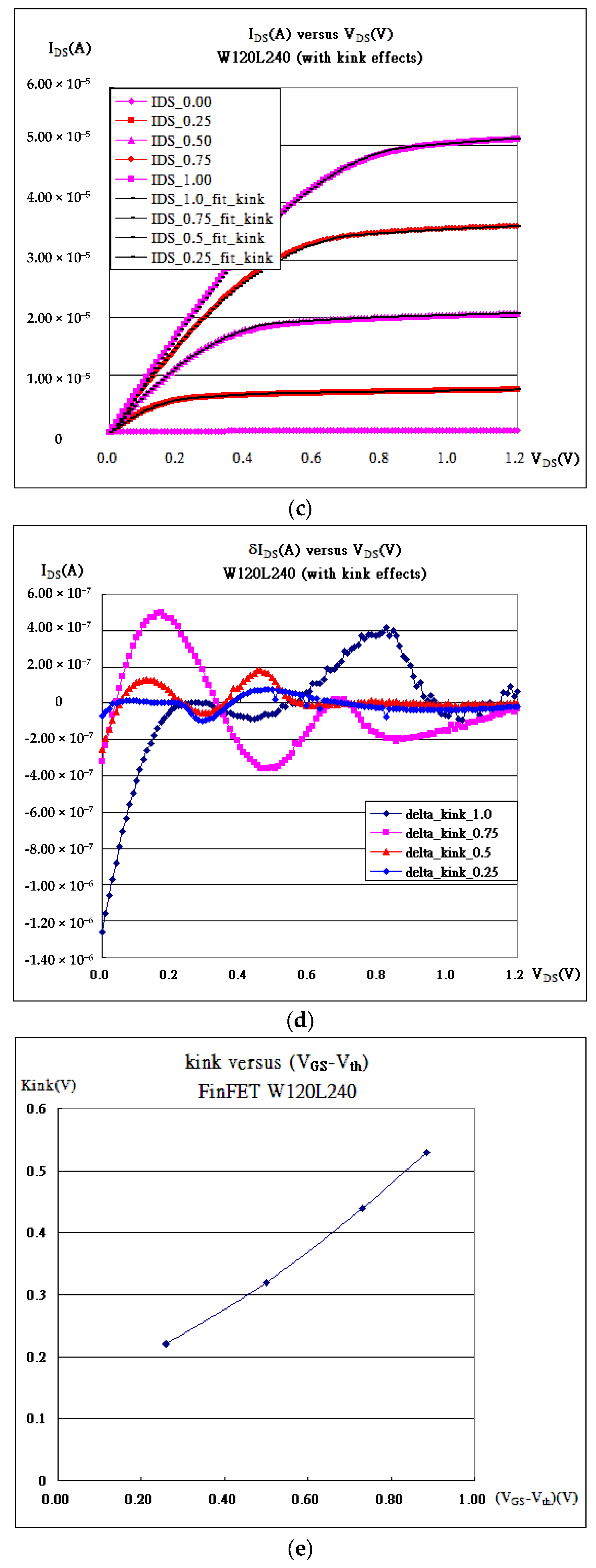

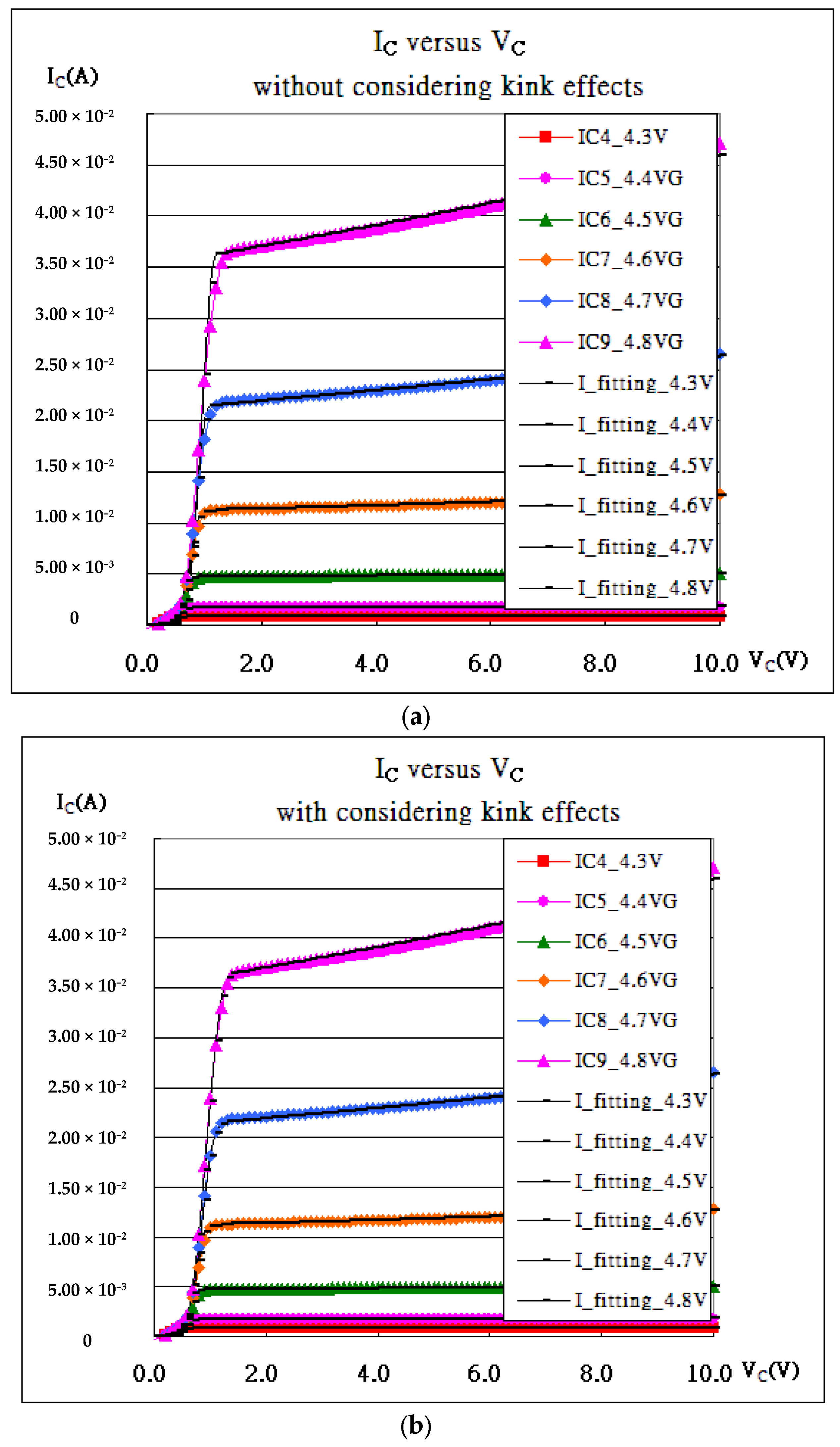

| Gate Bias (V) | ξkN (1/V2) | Vth_fit (V) | λ (1/V) | Io (A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

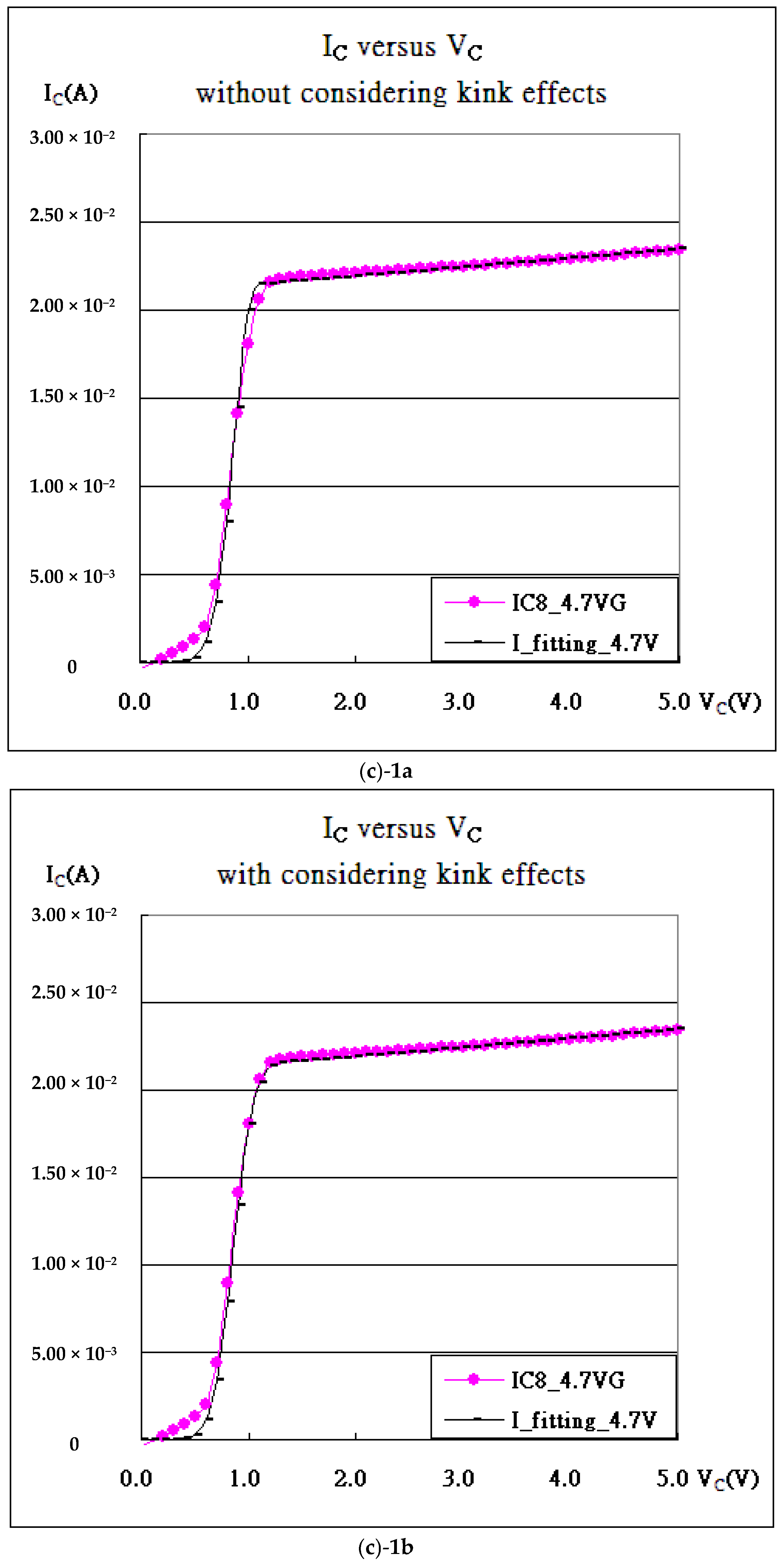

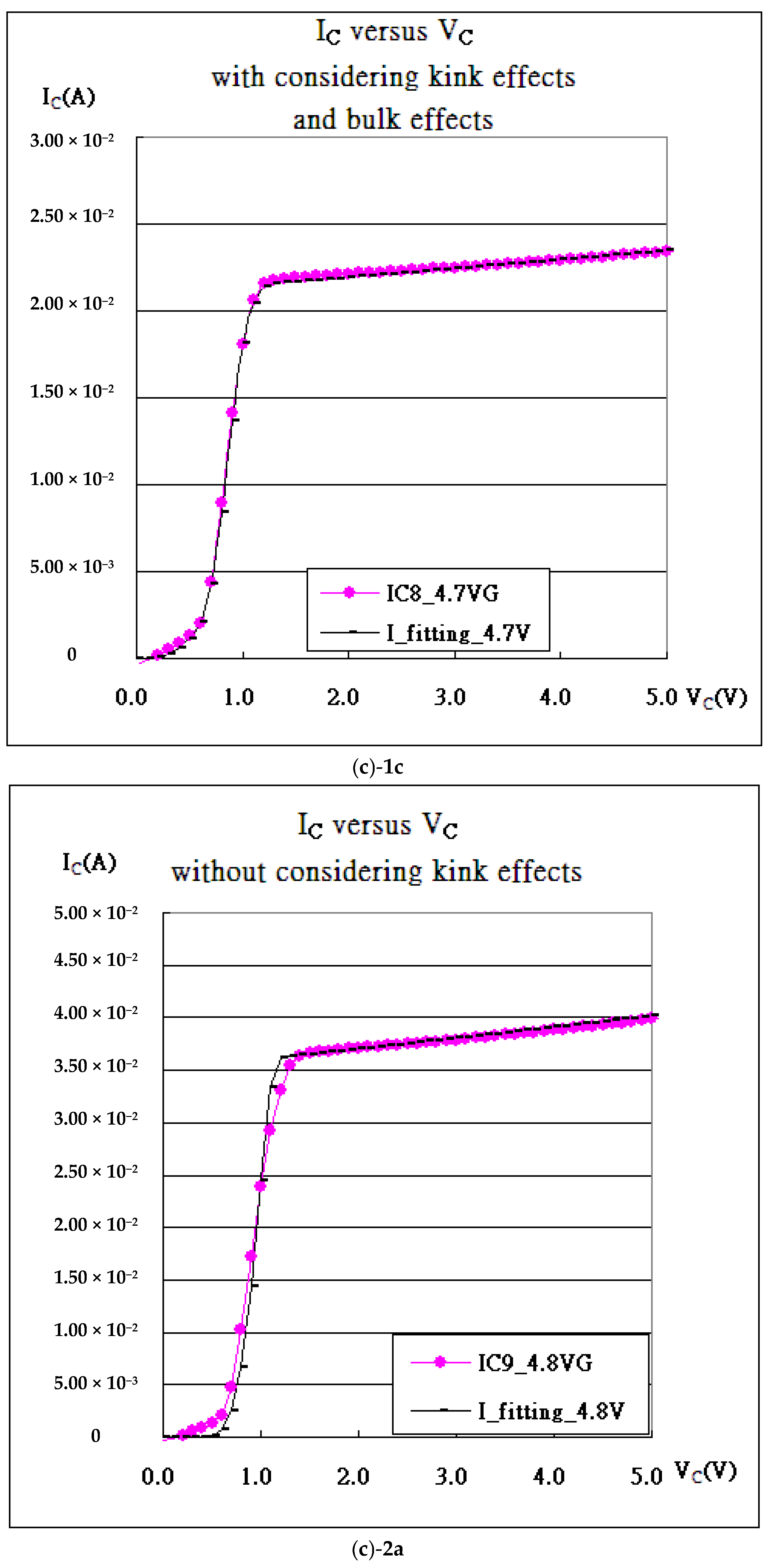

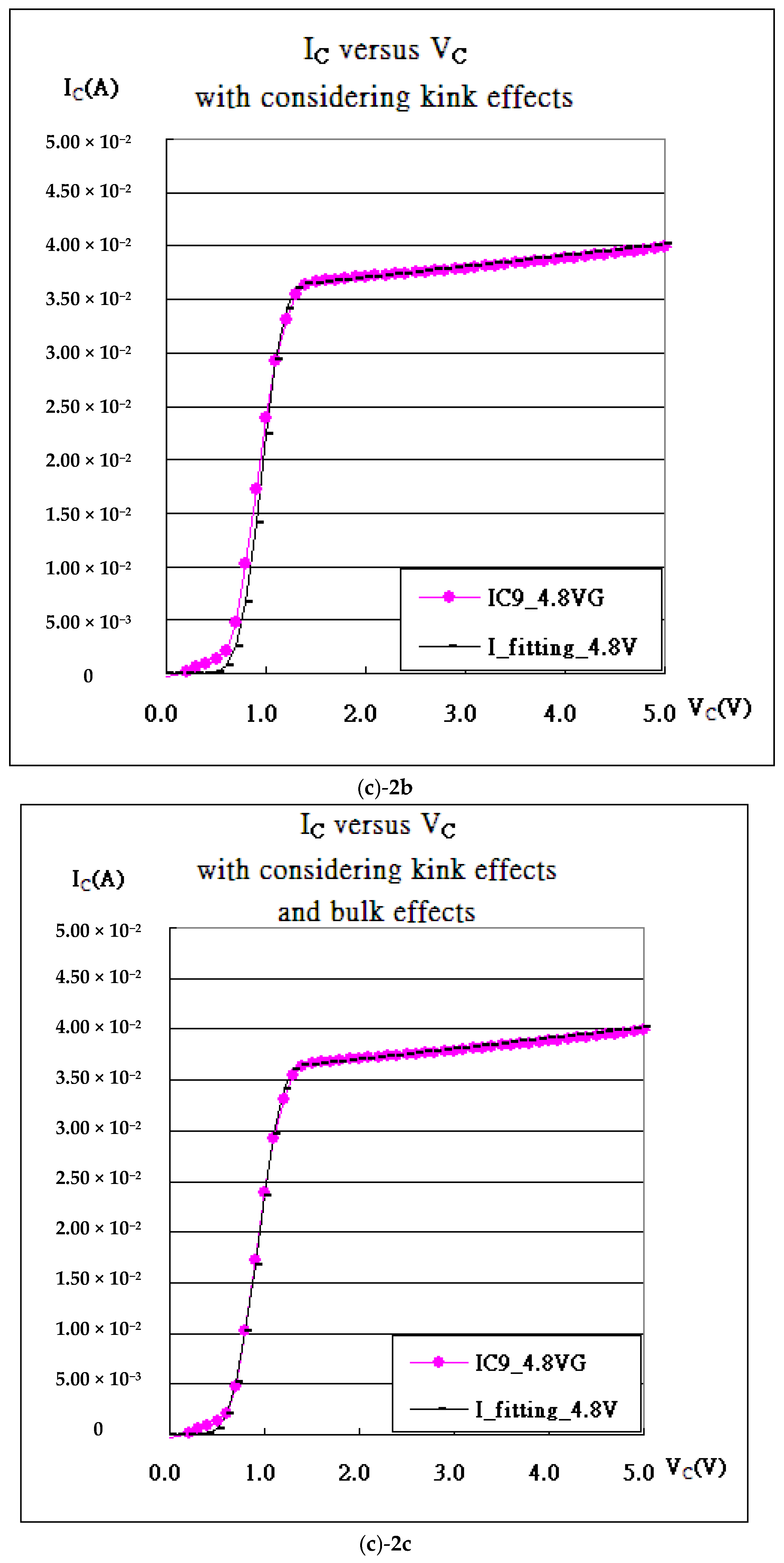

| VGS = 4.3 V | 51.142 | 3.63257 | 0.00065 | 9.29 × 10−9 |

| VGS = 4.4 V | 45.023 | 3.66703 | 0.00068 | 9.29 × 10−9 |

| VGS = 4.5 V | 38.201 | 3.66687 | 0.00070 | 8.35 × 10−9 |

| VGS = 4.6 V | 31.062 | 3.63793 | 0.00101 | 6.31 × 10−9 |

| VGS = 4.7 V | 26.195 | 3.62690 | 0.00151 | 5.90 × 10−9 |

| VGS = 4.8 V | 22.625 | 3.61557 | 0.00170 | 4.50 × 10−9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, H.-C.; Chi, S.-C.; Huang, B.-H.; Lai, T.-C.; Yang, H.-Y. Mobility of Carriers in Strong Inversion Layers Associated with Threshold Voltage for Gated Transistors. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121393

Yang H-C, Chi S-C, Huang B-H, Lai T-C, Yang H-Y. Mobility of Carriers in Strong Inversion Layers Associated with Threshold Voltage for Gated Transistors. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121393

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Hsin-Chia, Sung-Ching Chi, Bo-Hao Huang, Tung-Cheng Lai, and Han-Ya Yang. 2025. "Mobility of Carriers in Strong Inversion Layers Associated with Threshold Voltage for Gated Transistors" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121393

APA StyleYang, H.-C., Chi, S.-C., Huang, B.-H., Lai, T.-C., & Yang, H.-Y. (2025). Mobility of Carriers in Strong Inversion Layers Associated with Threshold Voltage for Gated Transistors. Micromachines, 16(12), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121393