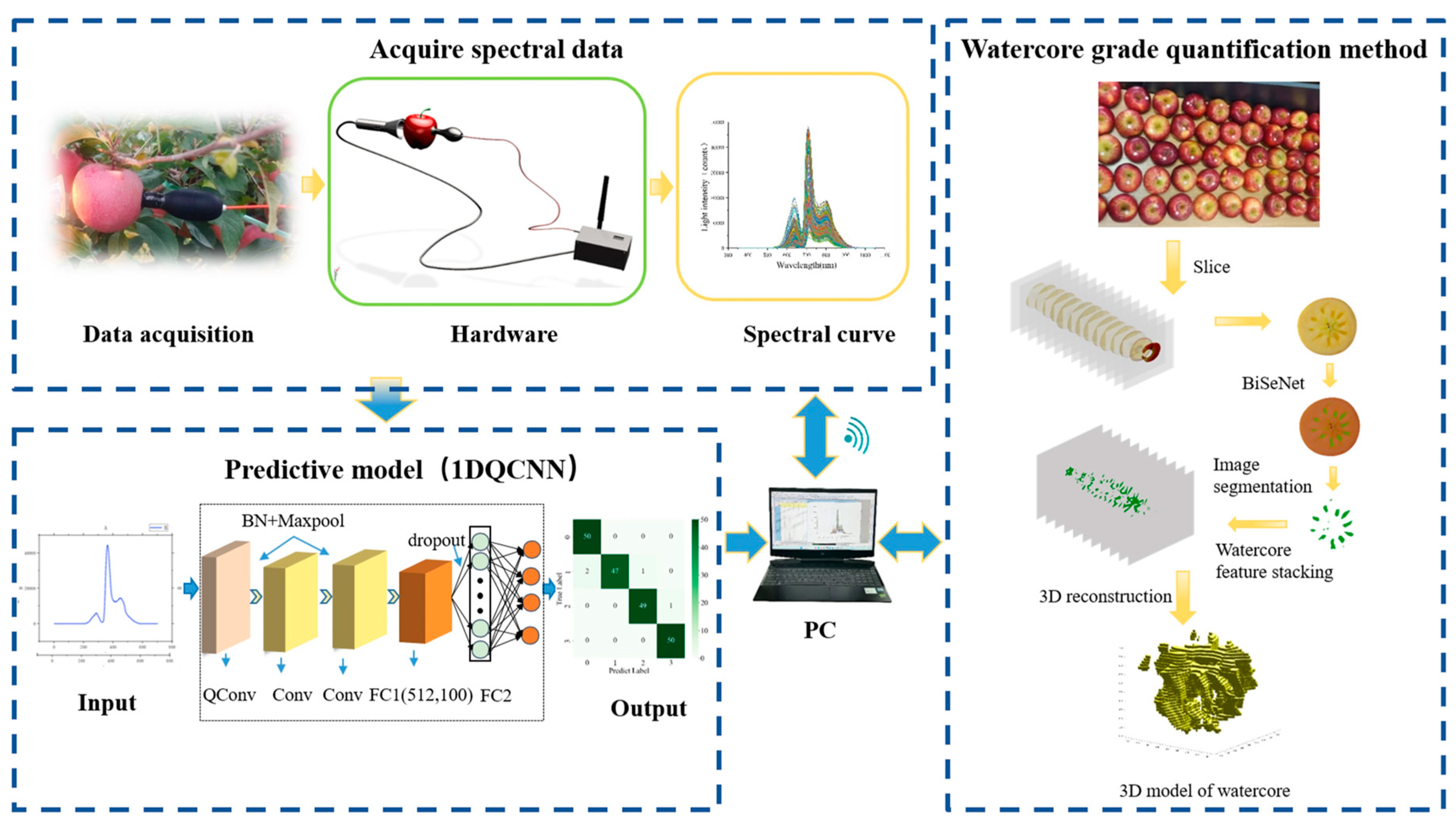

Design of a Portable Nondestructive Instrument for Apple Watercore Grade Classification Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

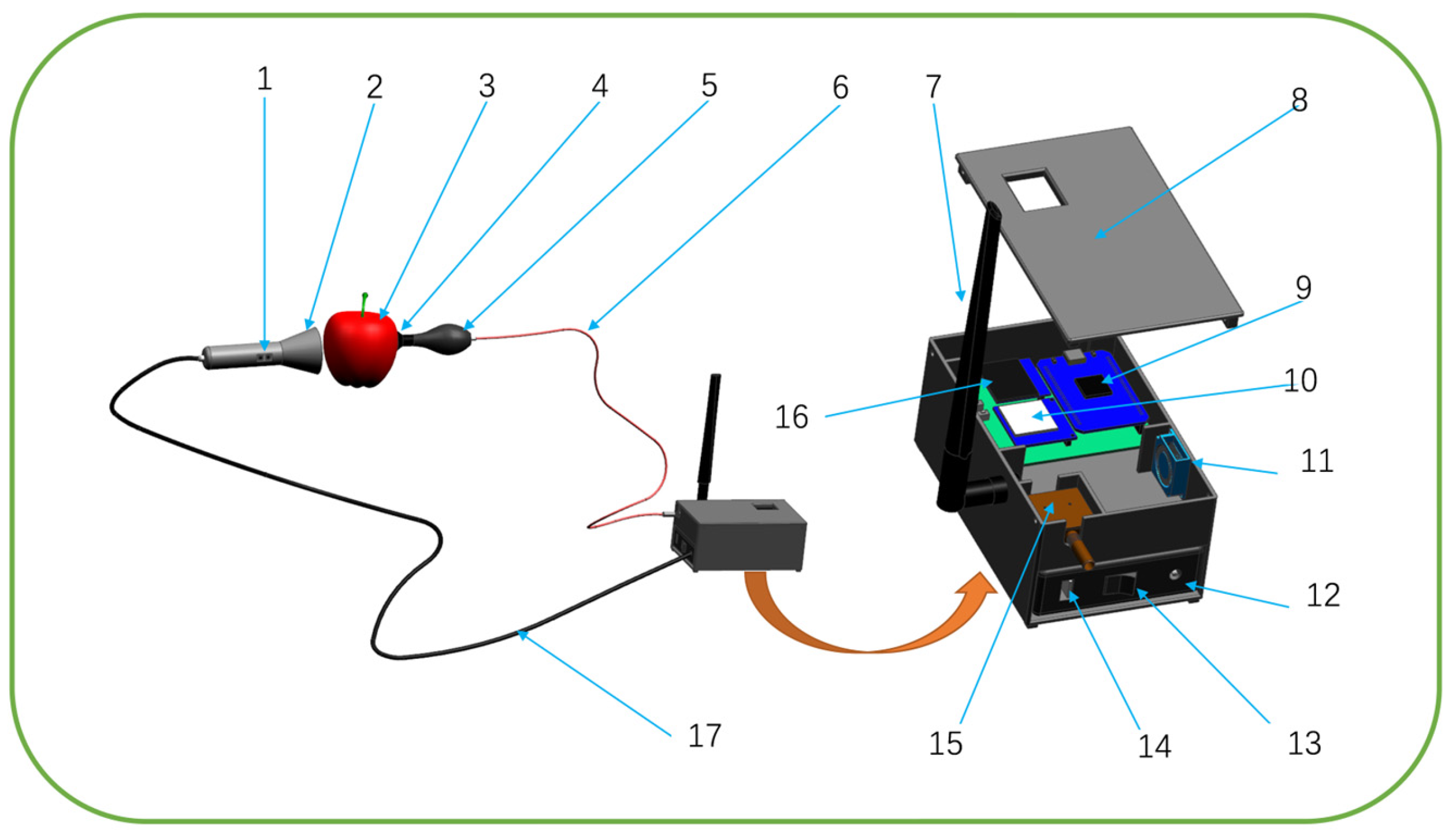

2. Instrument Design

2.1. Working Principle

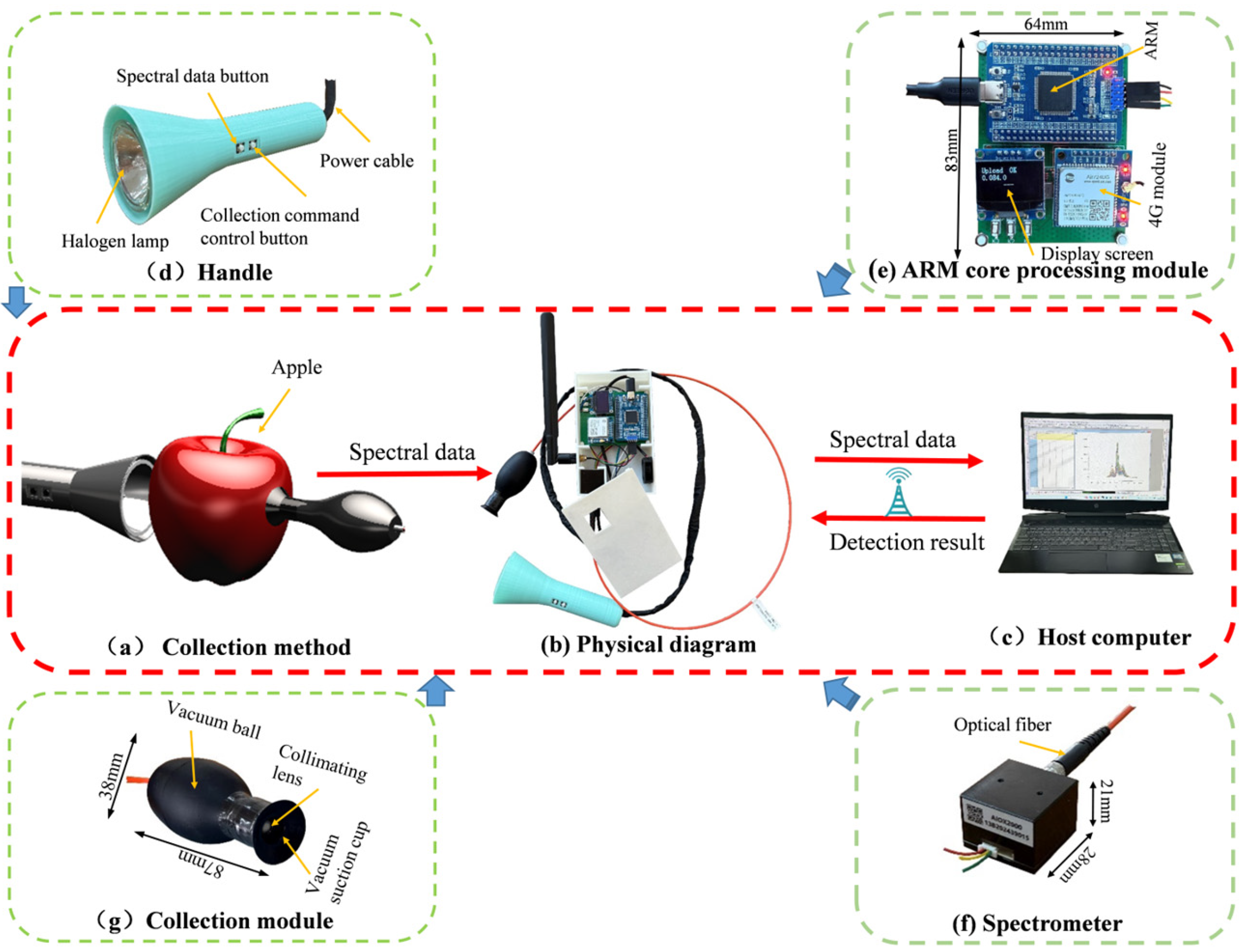

2.2. Hardware Design

2.2.1. The Design of ARM Processing Module

2.2.2. The Design of the Spectral Acquisition Module

2.2.3. Selection of Spectrometers and Other Accessories

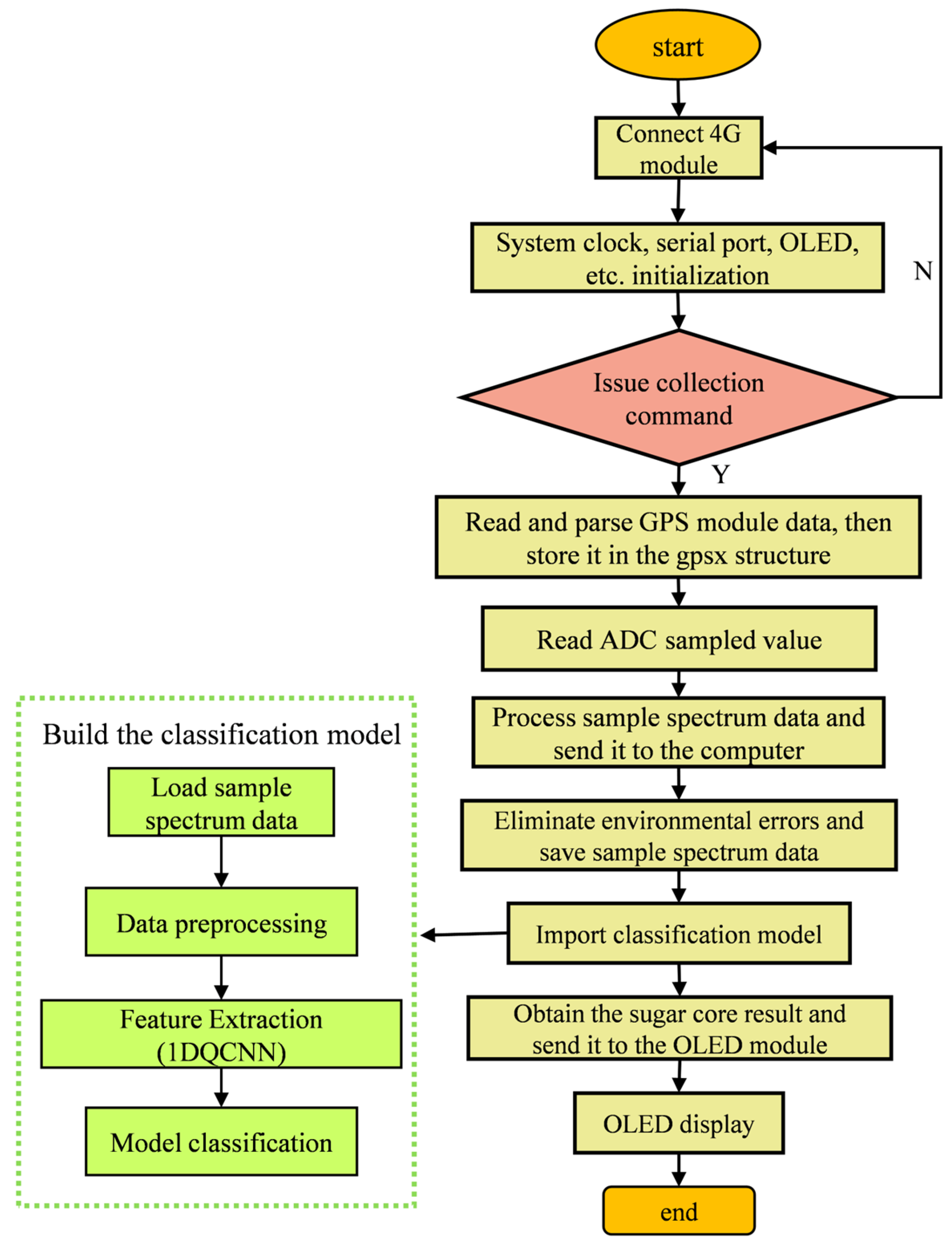

2.3. Main Program Design

3. Development of Watercore Classification Model

3.1. Sample Data Collection

3.1.1. Instrument Acquisition Method

3.1.2. Data Collection

3.2. New Method for Quantifying Apple Watercore Levels

3.3. Apple Watercore Level Classification Method Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy Technology

Convolutional Neural Network

3.4. Results and Discussion

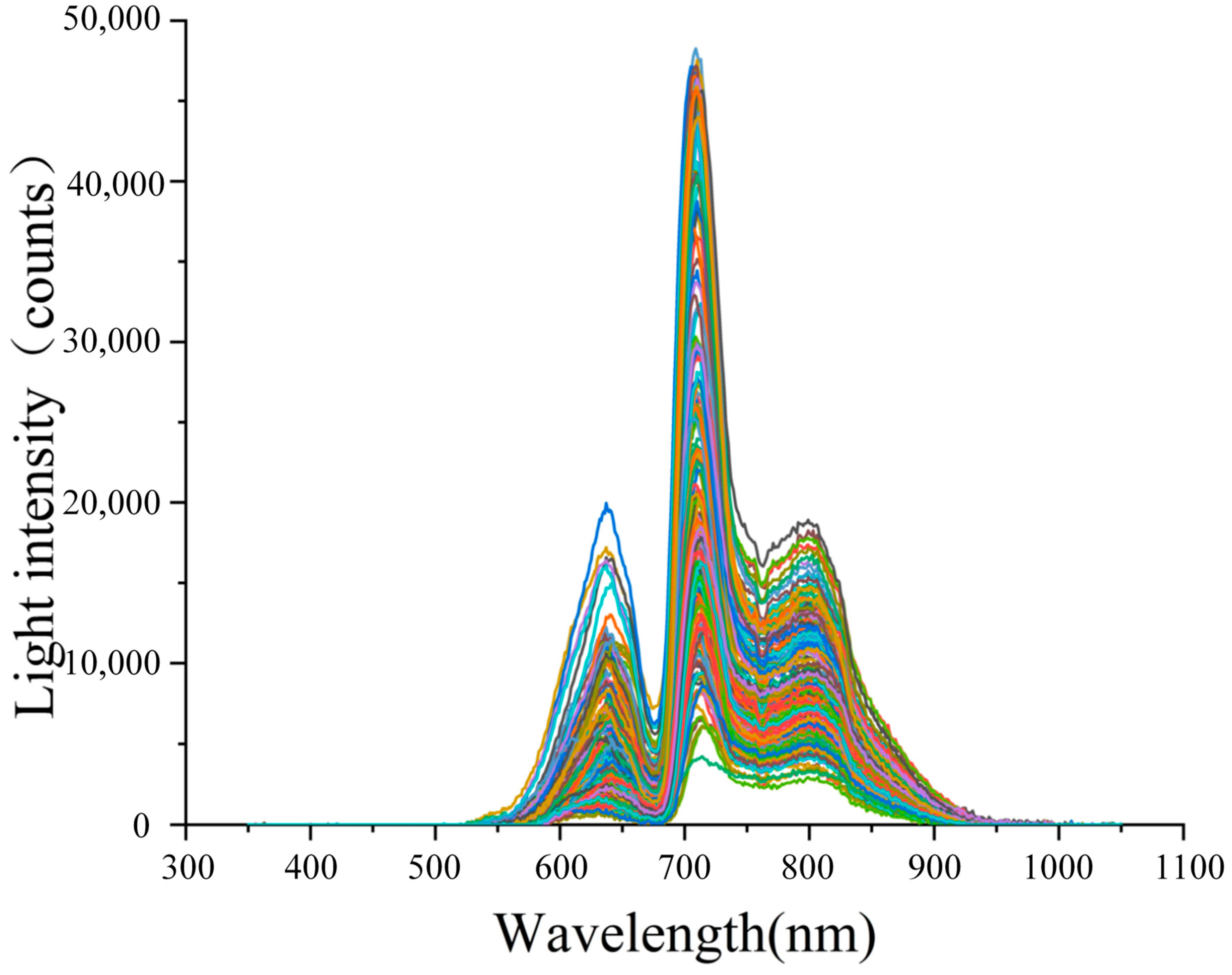

3.4.1. Data Collection Results

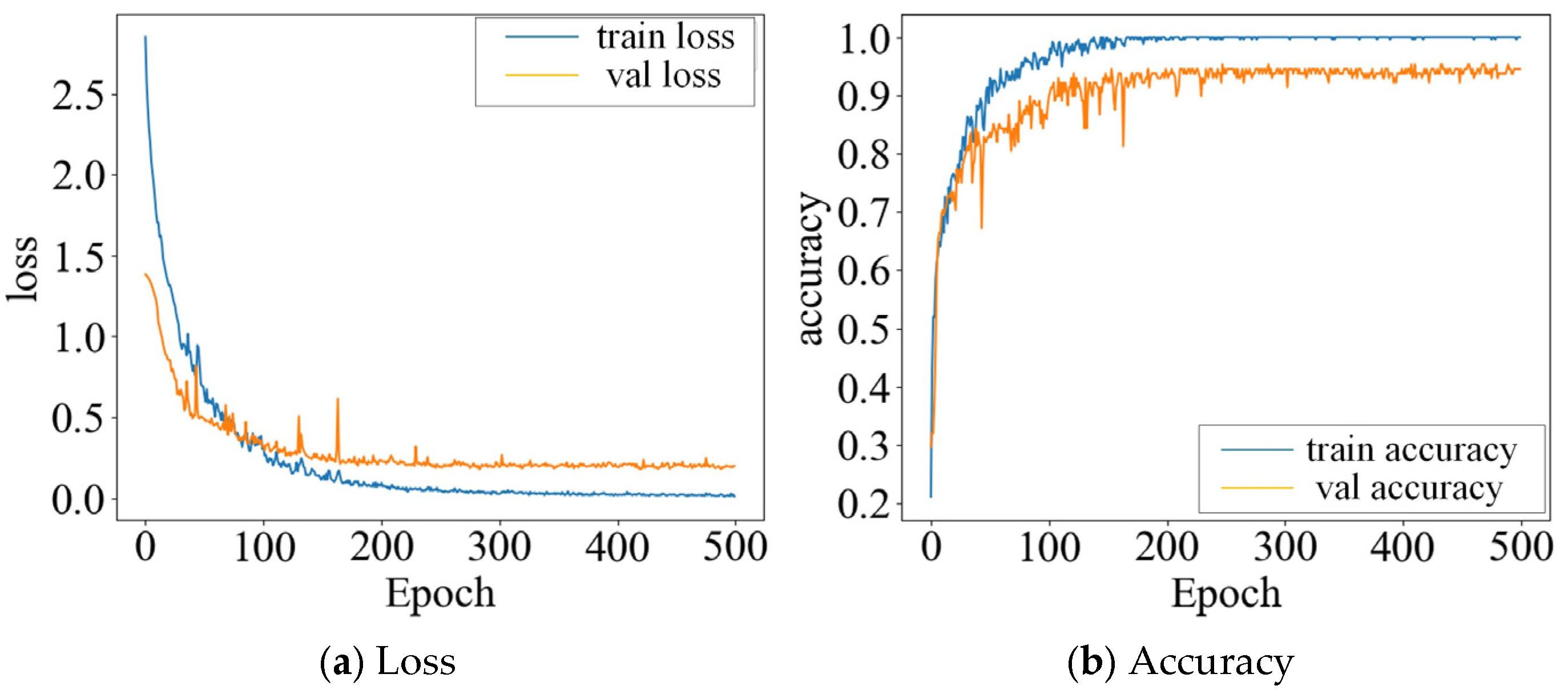

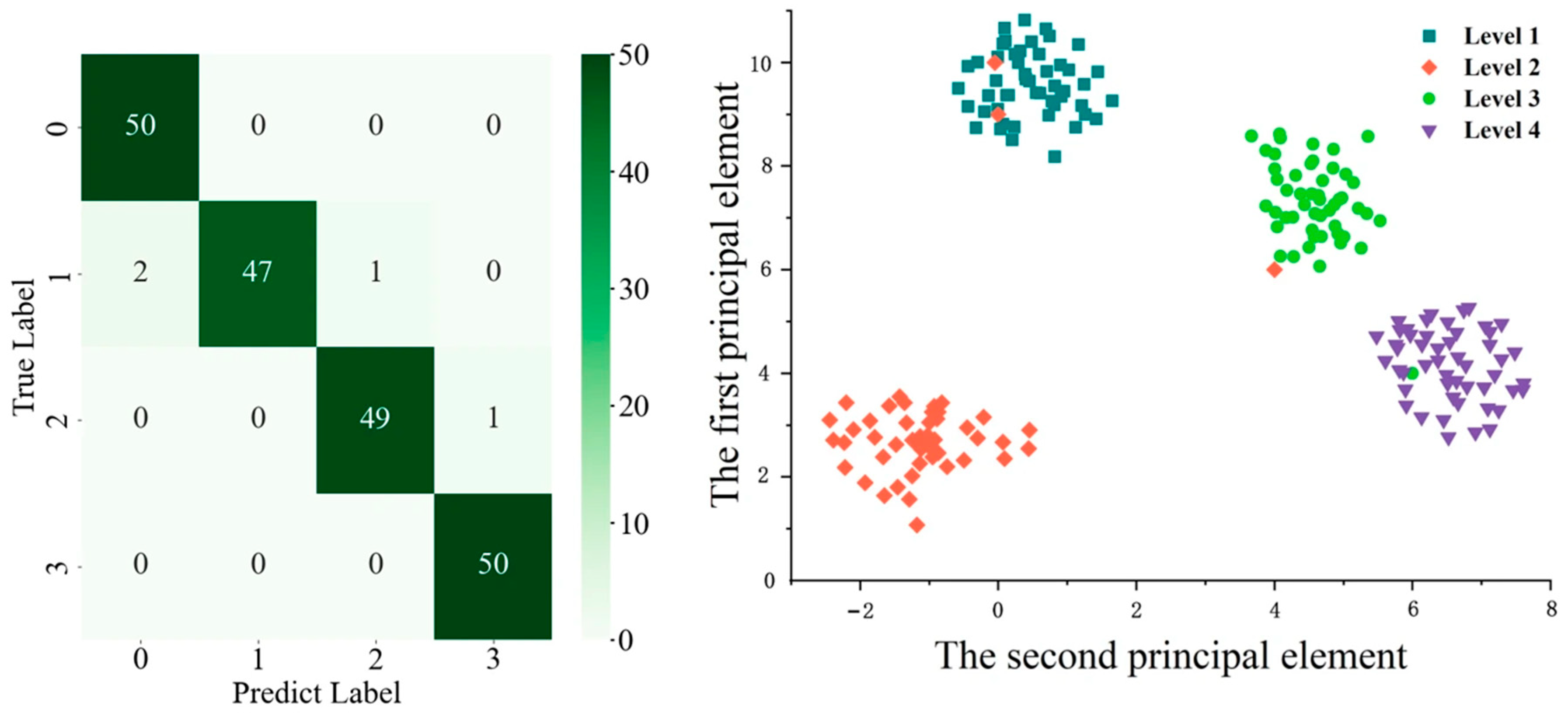

3.4.2. 1DQCNN Training Results

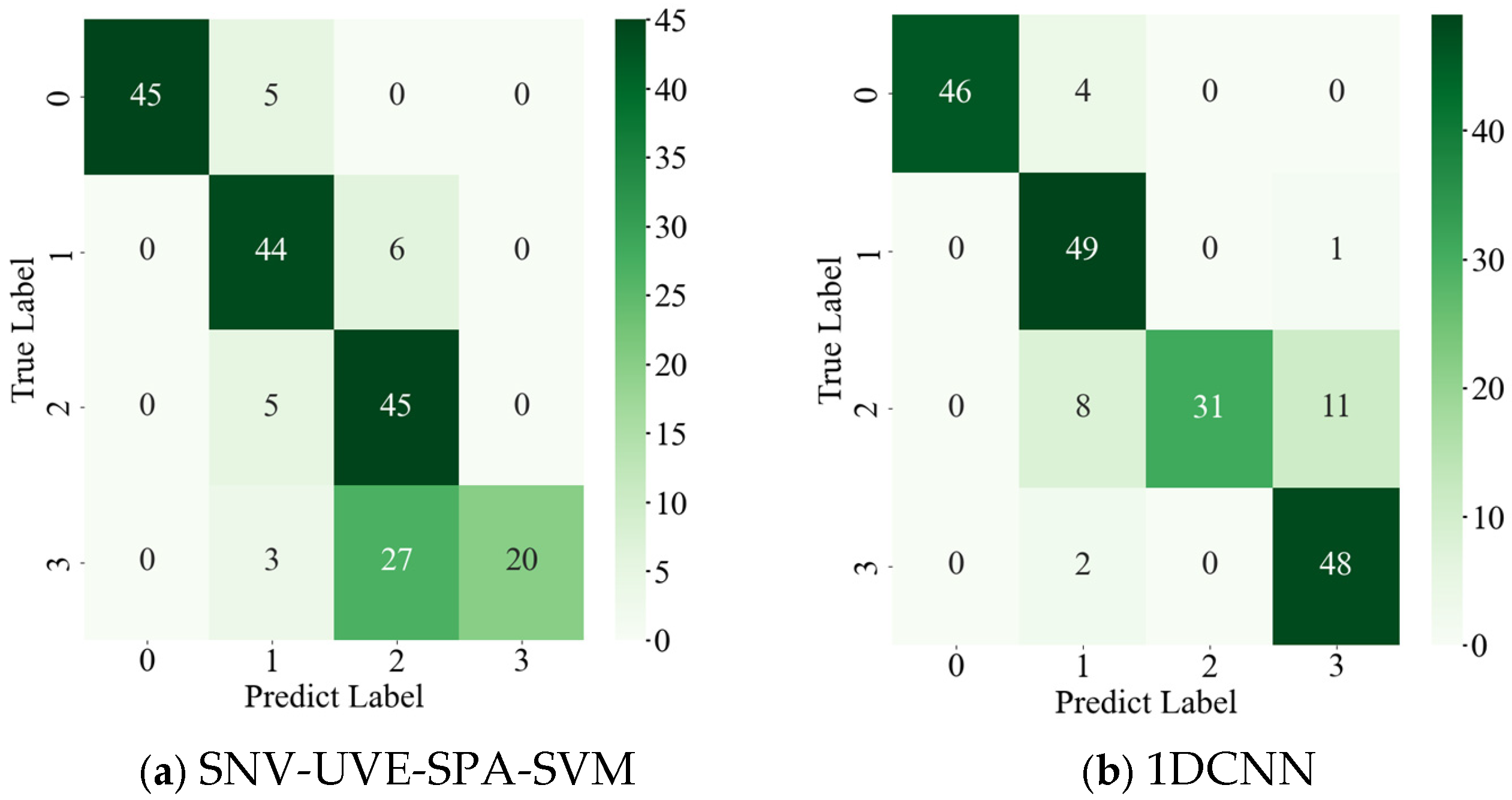

3.5. Comparison of Recognition Effects Between Traditional Methods and 1DCNN

4. Experimental Verification

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ke, B.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J. Assessing the Efficiency and Potential of China’s Apple Industry. Math. Probl. Eng. 2024, 2024, 7816792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Weng, F.; Shi, F.; Shao, L.; Huo, X. The evolutionary characteristics of apple production layout in China from 1978 to 2016. Ciência Rural 2021, 51, e20200688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muder, A.; Garming, H.; Dreisiebner-Lanz, S.; Kerngast, K.; Rosner, F.; Klosterneuburg, K.H.B.U.B.F.W.U.O.; Kličková, K.; Kurthy, G.; Cimer, K.; Bertazzoli, A.; et al. Apple production and apple value chains in Europe. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 87, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschida, A.; Stadlbauer, V.; Schwarzinger, B.; Maier, M.; Pitsch, J.; Stübl, F.; Müller, U.; Lanzerstorfer, P.; Himmelsbach, M.; Wruss, J.; et al. Nutrients, bioactive compounds, and minerals in the juices of 16 varieties of apple (Malus domestica) harvested in Austria: A four-year study investigating putative correlations with weather conditions during ripening. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D. Analysis of factors affecting the growth, development, and quality of apple fruits. Northwest Hortic. 2019, 3, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Guo, H.; Li, Q.; Kou, Z.; Li, Y. The influence of soil depth and tree age on soil enzyme activities and stoichiometry in apple orchards. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yi, J. Impact of Different Varieties on the Degree of Watercore and Quality of Apples: A Correlation Analysis. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Han, X.; Song, S.; Wang, H.; Xie, P.; Yang, H.; Li, S.; Wu, Y. Fruit quality characters and causes of watercore apple in high altitude areas of Guizho. J. South. Agric. 2021, 52, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Nie, J.; Li, J.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Kuang, L. Analysis and suggestions on the development of china’s apple industry. China Fruits 2014, 5, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ge, K.; Liu, Z.; Chen, N.; Ouyang, A.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, M. Non-destructive online detection of early moldy core apples based on Vis/NIR transmission spectroscopy. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Mei, N.; Zhang, S. Non-Destructive Detection Method of Apple Watercore: Optimization Using Optical Property Parameter Inversion and MobileNetV3. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, J.; Liu, C.; Feng, T. Non-destructive assessment of apple internal quality using rotational hyperspectral imaging. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, D.; Ren, X.; Ma, H. Nondestructive detection of apple watercore disease based on electric features. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yin, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, P.; Ma, Y.; Wu, H.; Hu, D.; Lu, Q. Apple Watercore Grade Classification Method Based on ConvNeXt and Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Agriculture 2025, 15, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, J.; Chu, X.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D. Research and application progress of near-infrared spectroscopy technology in china in the last five years. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 52, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Hu, J. Combination of interactance and transmittance modes of Vis/NIR spectroscopy improved the performance of PLS-DA model for moldy apple core. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 126, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, N.; Huck, C.W. Analyzing the Quality Parameters of Apples by Spectroscopy from Vis/NIR to NIR Region: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2023, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Sun, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Luan, Y. Application of Hyperspectral Imaging as a Nondestructive Technology for Identifying Tomato Maturity and Quantitatively Predicting Lycopene Content. Foods 2023, 12, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Choi, Y.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Tilahun, S.; Jeong, H. Prediction of Tannin Content and Quality Parameters in Astringent Persimmons Using Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1260644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Sun, Y.; Yu, D.; Lv, Y.; Han, Y. Identification of fig maturity based on near infrared spectroscopy and partial least square discriminant analysis. Food Mach. 2020, 36, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Sang, W.; Yang, C.; Zou, X. Application of nondestructive detection of fruit by near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging. Packag. Food Mach. 2024, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhshian, R.; Emadi, B.; Khojastehpour, M.; Golzarian, M.R.; Sazgarnia, A. Non-destructive evaluation of maturity and quality parameters of pomegranate fruit by visible/near infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Mazzoni, L.; Gagliardi, F.; Balducci, F.; Duca, D.; Toscano, G.; Mezzetti, B.; Capocasa, F. Application of the non-destructive NIR technique for the evaluation of strawberry fruits quality parameters. Foods 2020, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Égei, M.; Takács, S.; Palotás, G.; Palotás, G.; Szuvandzsiev, P.; Daood, H.G.; Helyes, L.; Pék, Z. Prediction of soluble solids and lycopene content of processing tomato cultivars by Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 845317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghooshkhaneh, N.; Golzarian, M.; Mollazade, K. VIS-NIR spectroscopy for detection of citrus core rot caused by Alternaria alternata. Food Control 2023, 144, 109320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W.; Fan, S.; Li, J. Online detection of apples with moldy core using the Vis/NIR full-transmittance spectra. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xiang, S.; He, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, J. Prediction of Soluble Solids Content in Mature Apples Based on Visible/Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Functional Linear Regression Model. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2024, 44, 1905–1912. Available online: https://www.gpxygpfx.com/EN/10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2024)07-1905-08 (accessed on 3 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Guo, P.; Ma, Y. Identification of apple watercore based on ConvNeXt and Vis/NIR spectra. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 142, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wu, Q.; Yan, J.; Luo, X.; Xu, H. On-line evaluation of watercore in apples by visible/near infrared spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2019 ASABE Annual International Meeting; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2019; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J. Online Detection of Watercore Apples by Vis/NIR Full‑Transmittance Spectroscopy Coupled with ANOVA Method. Foods 2021, 10, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, C.; Guo, P.; Wu, H.; Hu, D. An OCRNet-Based Method for Assessing Apple Watercore in Cold and Cool Regions of Yunnan Province. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2021); PMLR: Melbourne, Australia, 2021; Volume 139, pp. 10096–10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Qin, B. Development of a Portable Nondestructive Testing Instrument for Apple Sugar Content. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wang, Q.; Tian, X.; Yang, G.; Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, W. Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solids content of apples using a developed portable Vis/NIR device. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 193, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zou, Y.; Sun, C.; Jayan, H.; Jiang, S.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zou, X. Nondestructive determination of edible quality and watercore degree of apples by portable Vis/NIR transmittance system combined with CARS-CNN. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 4058–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, Q. Design and Test of Portable Red Globe Grape Extraction Multi-quality Visible/Near Infrared Detector. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, S.; Huang, W. Optimization of Whole-Transmission Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Model for Online Detection of Apple Whole Fruit Sugar Content. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2022, 42, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, M.; Ali, S.; Wu, J.; Shi, J.; Ouyang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Zou, X. Nondestructive monitoring storage quality of apples at different temperatures by near‑infrared transmittance spectroscopy. Food Sci. Nutr 2020, 8, 3793–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, H.; Xie, L.; Ying, Y. Effect of Measurement Position on Prediction of Apple Soluble Solids Content (SSC) by an On-line Near-Infrared (NIR) System. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Yan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Proteomic analysis reveals dynamic regulation of fruit development and sugar and acid accumulation in apple. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 884–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Guo, P.; Ma, Y.; Wu, H.; Hu, D.; Lu, Q. Nondestructive detection of apple watercore disease content based on 3D watercore model. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Fu, C.; Gao, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, W. Research on the Identification Method of Maize Seed Origin Using NIR Spectroscopy and GAF-VGGNet. Agriculture 2024, 14, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M. Multi-Scale Spatial Attention-Based Multi-Channel 2D Convolutional Network for Soil Property Prediction. Sensors 2024, 24, 4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Sun, Y. Application of Convolutional Neural Networks in Image Recognition. Softw. Eng. 2019, 22, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Xiong, J.; Wang, G. Universal approximation with quadratic deep networks. Neural Netw. 2020, 124, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification Model | Evaluation Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Points | Accuracy | Recall Rate | |

| 1DQCNN | 0.9799 | 0.9805 | 0.98 |

| 1DCNN | 0.8695 | 0.8944 | 0.87 |

| SNV-UVE-SPA-SVM | 0.7853 | 0.8381 | 0.785 |

| Watercore Level | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Quantity (pcs) | 56 | 53 | 50 | 41 |

| Measured Quantity(pcs) | 55 | 50 | 48 | 39 |

| Accuracy(%) | 0.98 | 0.943 | 0.96 | 0.951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Yin, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, D. Design of a Portable Nondestructive Instrument for Apple Watercore Grade Classification Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121357

Wu H, Lin Y, Zhang W, Cao Z, Zhao C, Yin Z, Lu Y, Liu L, Hu D. Design of a Portable Nondestructive Instrument for Apple Watercore Grade Classification Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121357

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Haijian, Yong Lin, Wenbin Zhang, Zikang Cao, Chunlin Zhao, Zhipeng Yin, Yue Lu, Liju Liu, and Ding Hu. 2025. "Design of a Portable Nondestructive Instrument for Apple Watercore Grade Classification Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121357

APA StyleWu, H., Lin, Y., Zhang, W., Cao, Z., Zhao, C., Yin, Z., Lu, Y., Liu, L., & Hu, D. (2025). Design of a Portable Nondestructive Instrument for Apple Watercore Grade Classification Based on 1DQCNN and Vis/NIR Spectroscopy. Micromachines, 16(12), 1357. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121357