Dynamics of h-Shaped Pulse to GHz Harmonic State in a Mode-Locked Fiber Laser

Abstract

1. Introduction

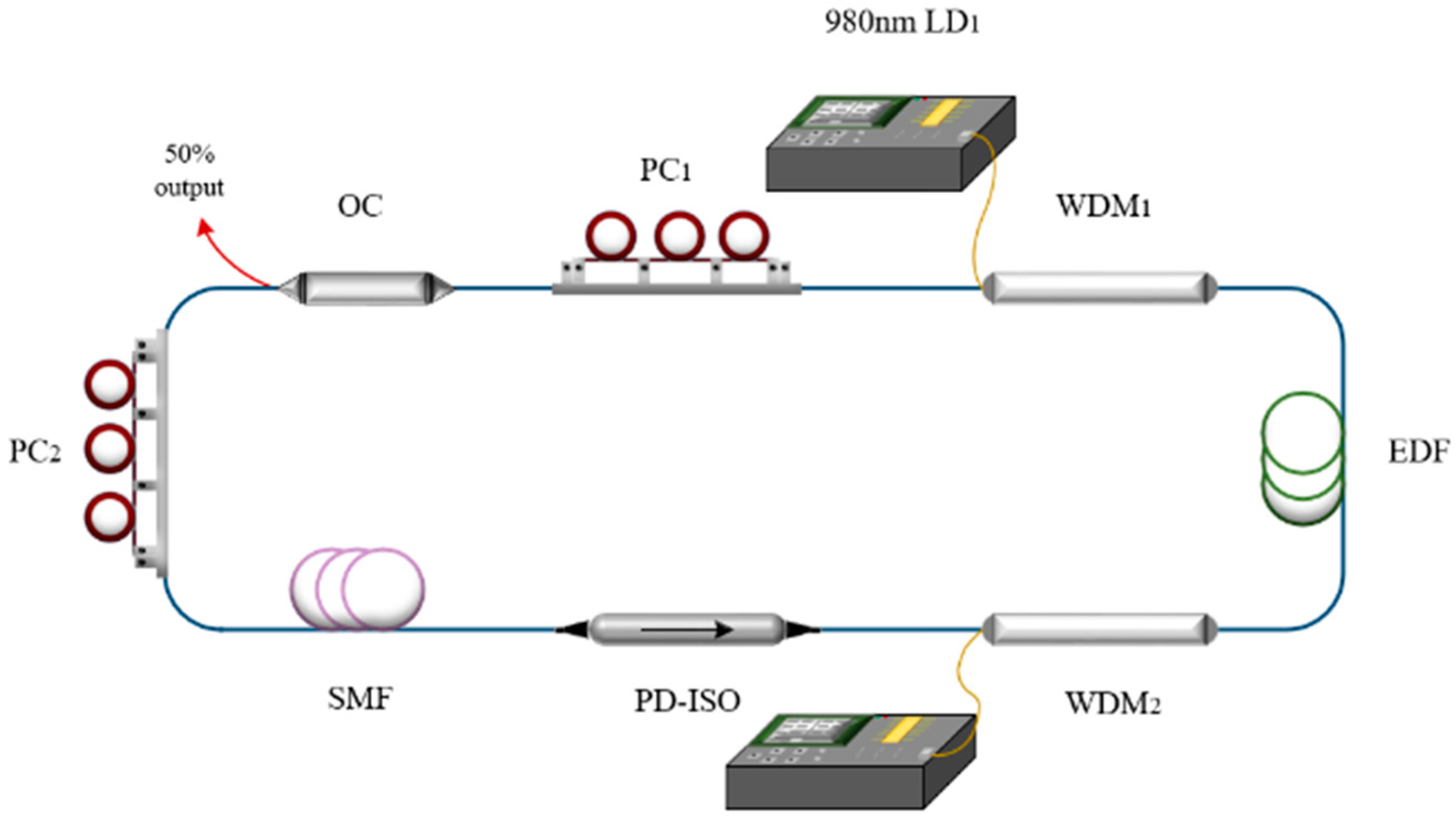

2. Methods

3. Results

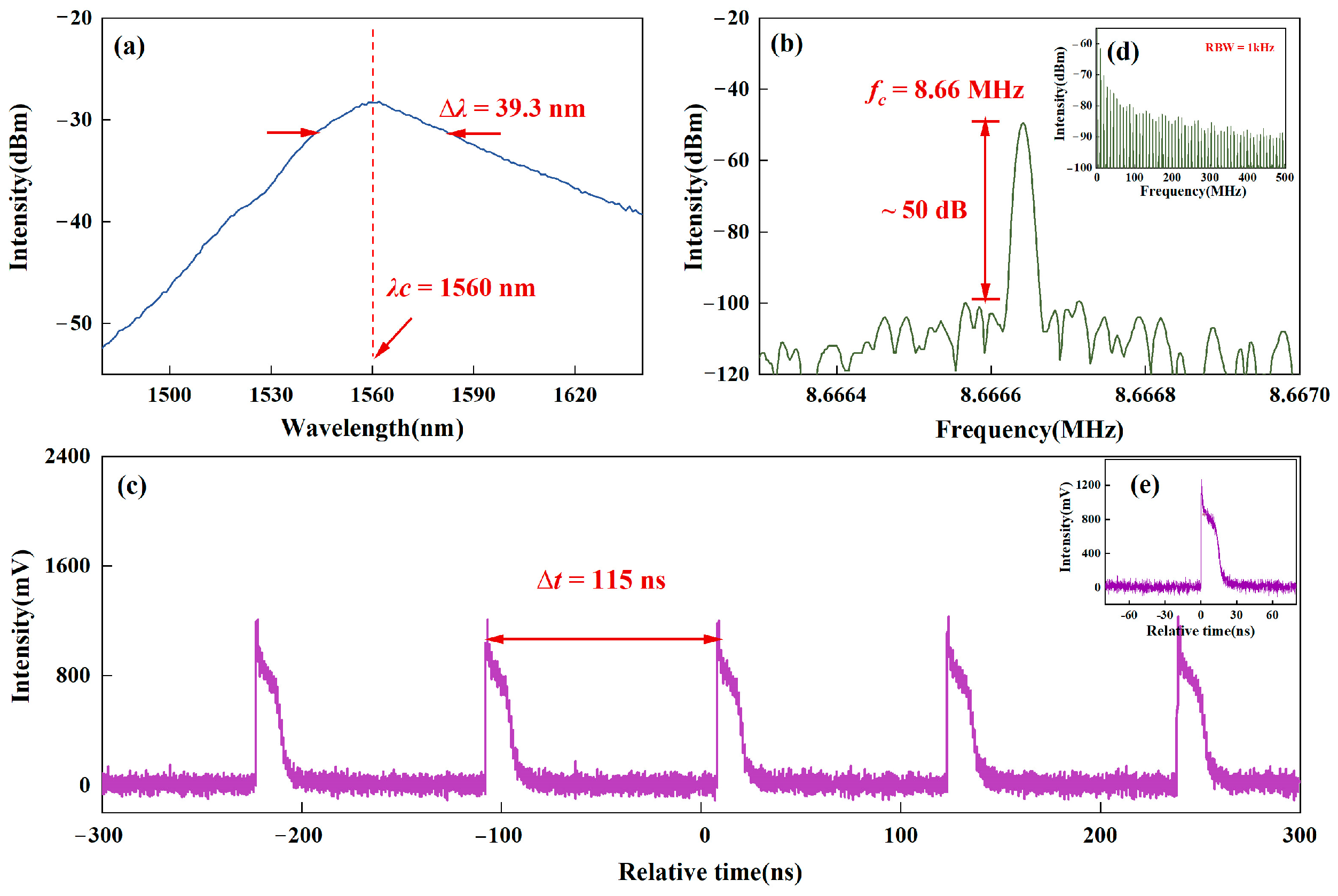

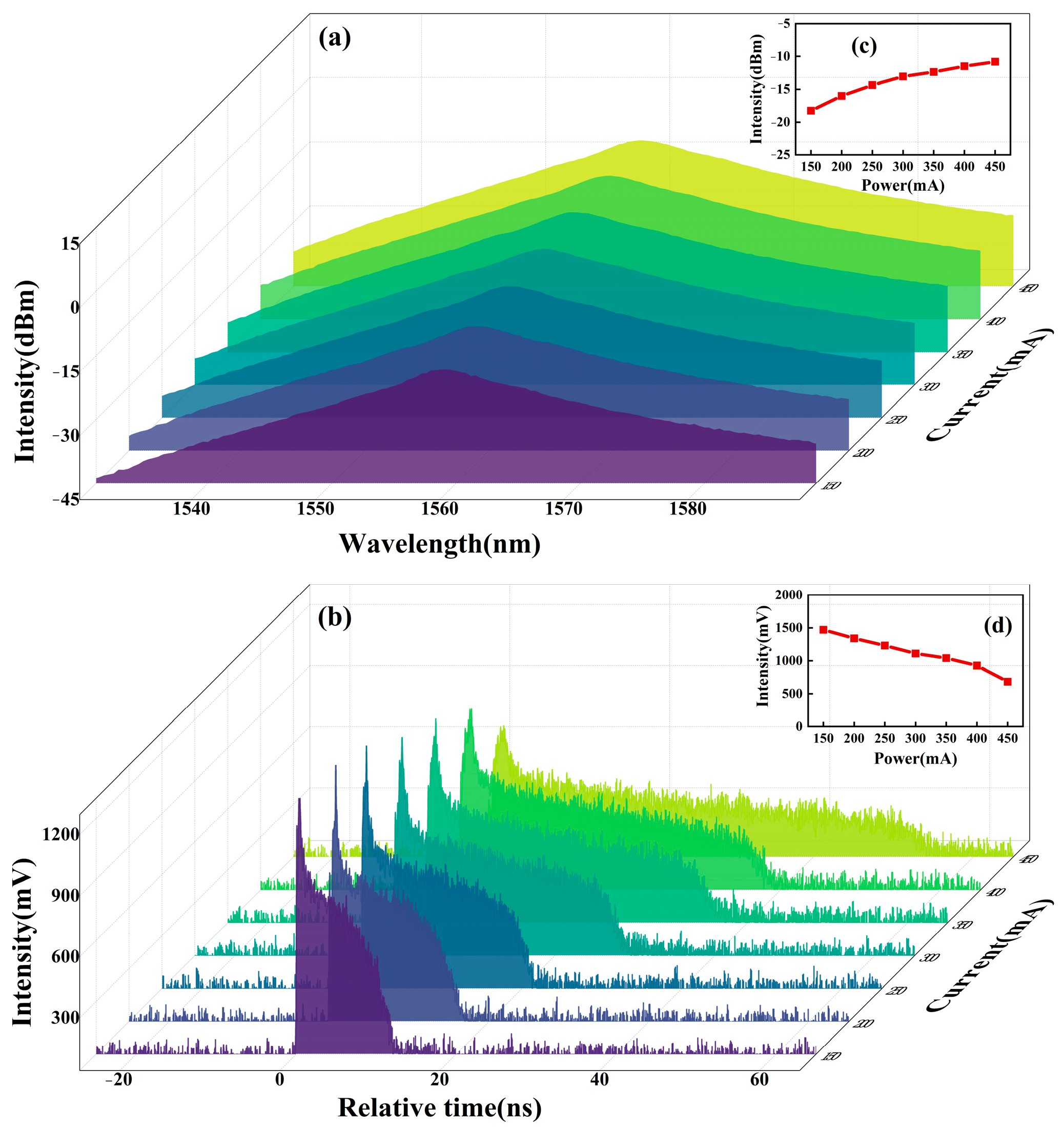

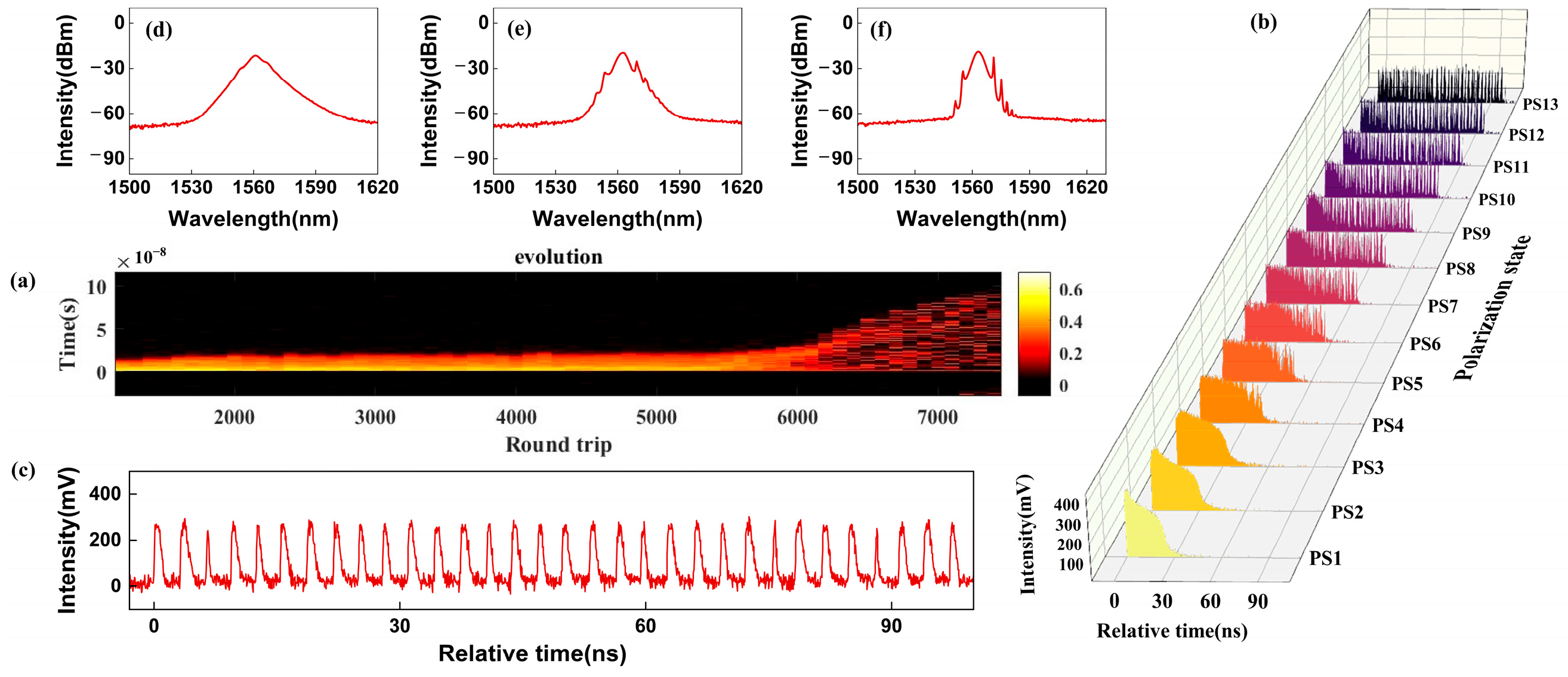

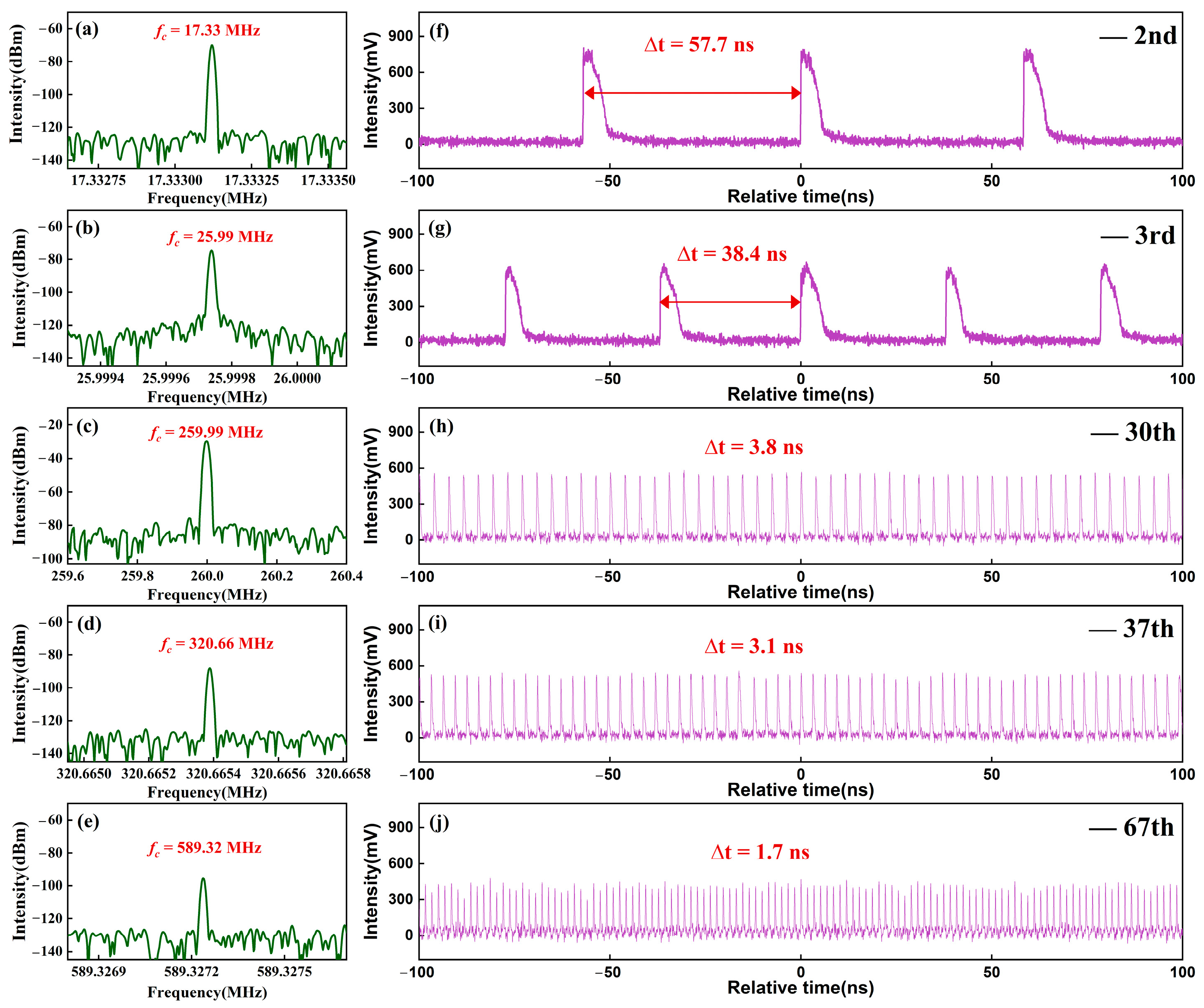

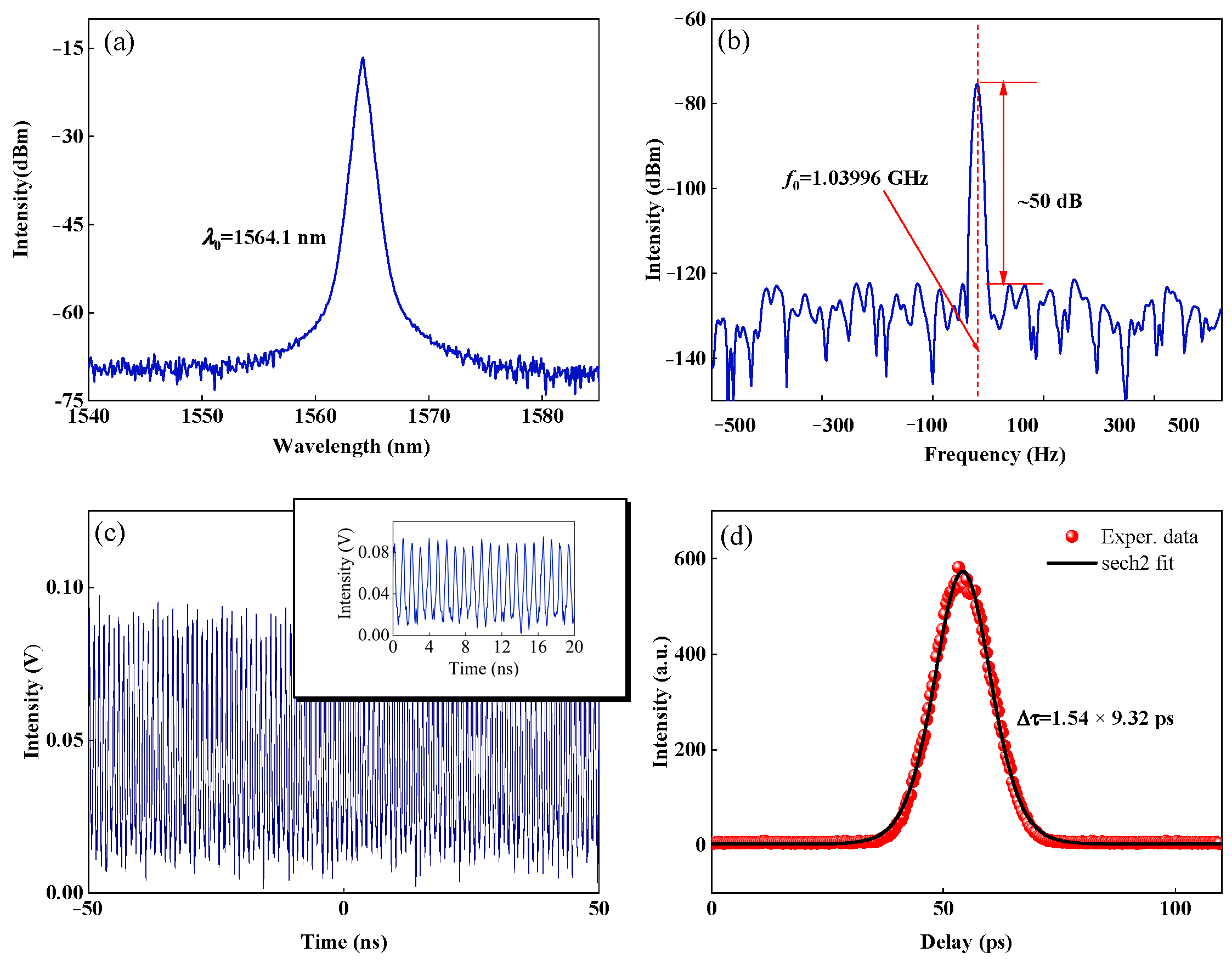

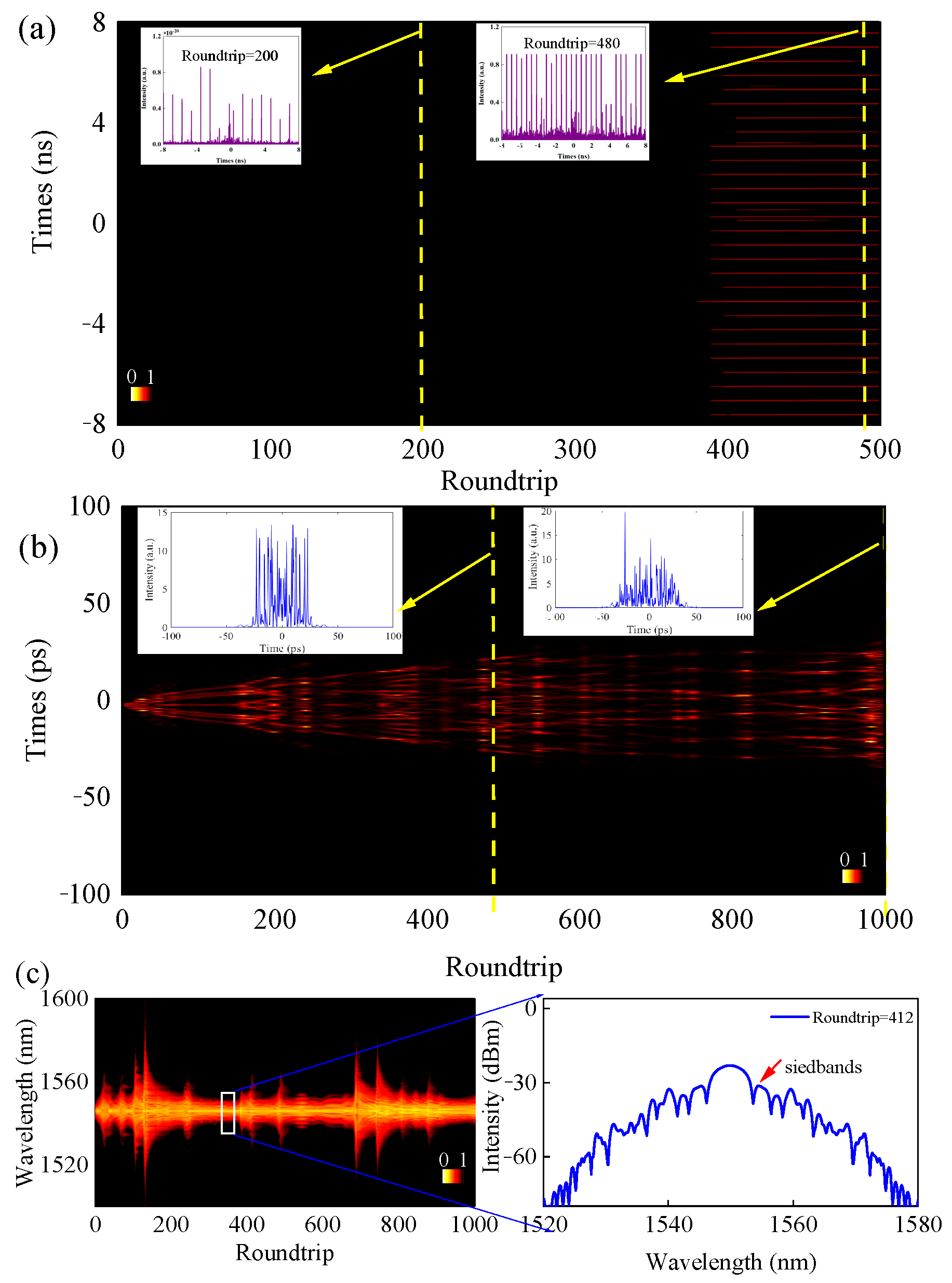

3.1. Experimental Results

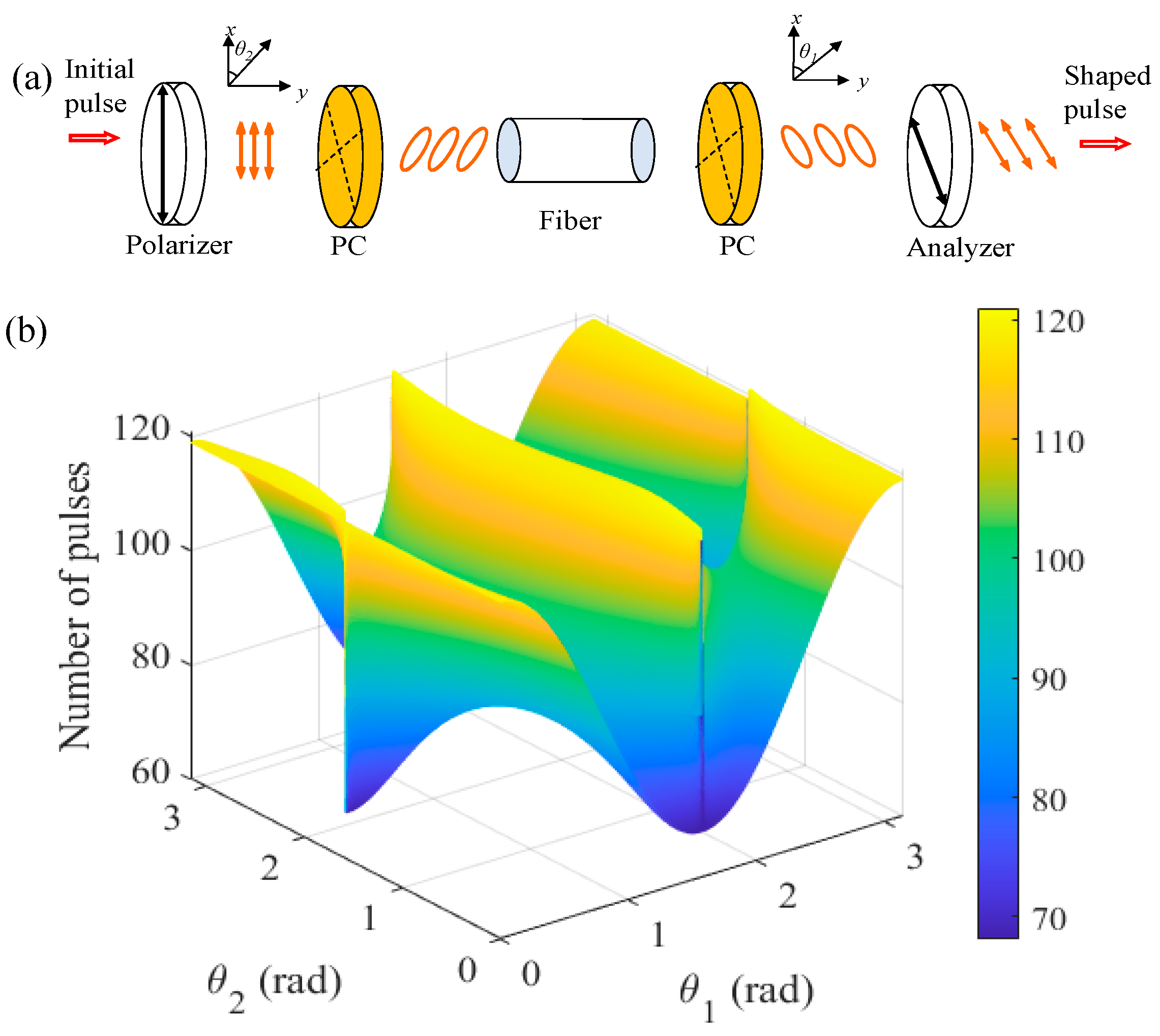

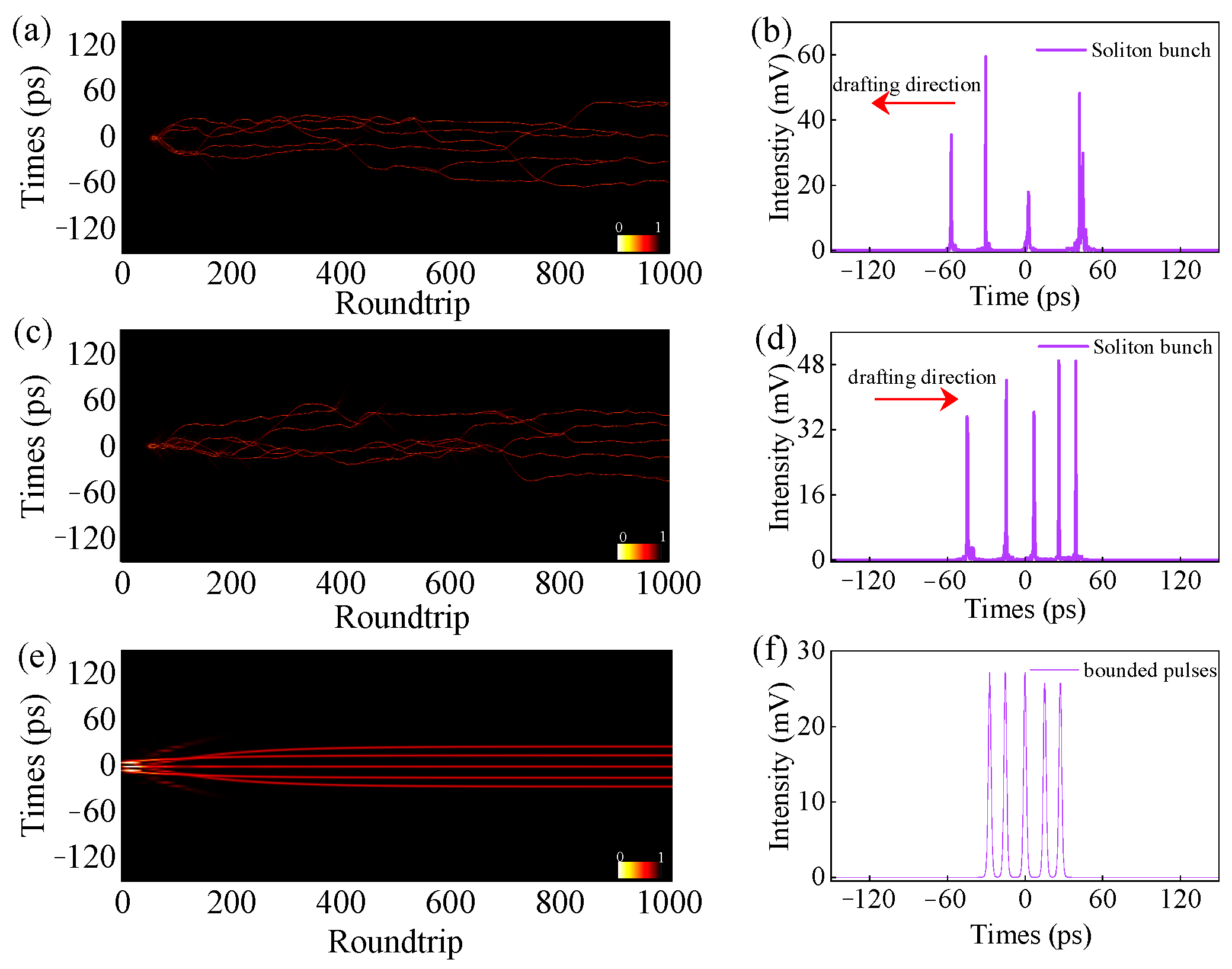

3.2. Simulation and Discussion

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mao, D.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Y.; Zeng, C.; Yun, L.; Luo, Z.; Li, T.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, J. Phase-matching-induced near-chirp-free solitons in normal-dispersion fiber lasers. Light-Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.R.; Qi, M.T.; Li, X.P.; Xue, Z.; Lu, C.H.; Cheng, J.W.; Han, D.D.; Li, L. Optical nonlinearity of violet phosphorus and applications in fiber laser. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2024, 41, 014202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Yang, G.; Li, D.; Luo, P.; Wang, R.; Du, Y.; Mao, D.; Zhao, J. Self-synchronized multi-color Q-switched fiber laser using a parallel-integrated fiber Bragg grating. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2024, 22, 061402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, C.; Du, Y.; He, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, J. Synchronized multi-wavelength soliton fiber laser via intracavity group delay modulation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gao, B.; Wen, H.; Ma, C.; Huo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, G.; Liu, L. Pure-high-even-order dispersion bound solitons complexes in ultra-fast fiber lasers. Light-Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qi, M.; Li, X.; Xue, Z.; Cheng, J.; Lu, C.; Han, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F. Soliton interaction in a MXene-based mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 38688–38698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulimany, K.; Lib, O.; Masri, G.; Klein, A.; Fridman, M.; Grelu, P.; Gat, O.; Steinberg, H. Bidirectional soliton rain dynamics induced by casimir-like interactions in a graphene mode-locked fiber laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 133902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.K.; Erkintalo, M.; Murdoch, S.G.; Coen, S. Ultraweak long-range interactions of solitons observed over astronomical distances. Nat. Photon. 2013, 7, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.W.; Jia, K.L.; Ji, S.K.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.Y. Soliton rains with isolated solitons induced by acoustic waves in a nonlinear multimodal interference-based fiber laser. Laser Phys. 2023, 33, 035101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herink, G.; Kurtz, F.; Jalali, B.; Solli, D.R.; Ropers, C. Real-time spectral interferometry probes the internal dynamics of femtosecond soliton molecules. Science 2017, 356, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrianov, A.; Kim, A. Widely stretchable soliton crystals in a passively mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 25202–25216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarov, A.; Leblond, H.; Sanchez, F. Passive harmonic mode-locking in a fiber laser with nonlinear polarization rotation. Opt. Commun. 2006, 267, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.X.; Haus, H.A.; Ippen, E.P.; Wong, W.S.; Sysoliatin, A. Gigahertz-repetition-rate mode-locked fiber laser for continuum generation. Opt. Lett. 2000, 25, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xue, Z.; Pang, L.; Xiao, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, W. Saturable absorption properties and ultrafast photonics applications of HfS3. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Jia, K.; Chen, L.; Chen, G.; Hu, G.; Wu, T.; Li, H.; He, J.; Zhou, Z. Dual-comb soliton rains based on polarization multiplexing in a single-walled carbon nanotube mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2024, 22, 051402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, L.; Tang, D.; Shen, D. Cavity-birefringence-dependent h-shaped pulse generation in a thulium-holmium-doped fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Du, G.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, P.; Wang, J.; Dong, F.; Lue, Q.; Guo, C.; Ruan, S. Frequency domain resolved investigation of unitary h-shaped pulses. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 14842–14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, G. Higher-order nonlinear effects on optical soliton propagation and their interactions. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2024, 41, 074204. [Google Scholar]

- Grelu, P.; Belhache, F.; Gutty, F.; Soto-Crespo, J.M. Relative phase locking of pulses in a passively mode-locked fiber laser. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2003, 20, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svelto, O.; Hanna, D.C. Principles of Lasers; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| (θ1, θ2)/rad | N | Λ/(m·s)−1 | 2δG/m−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (2.31, 1.8) | 5 | 1.03 × 103 | 8.8 × 10−7 |

| (0.3, 0.72) | 12 | 1.31 × 103 | 3.7 × 10−7 |

| (1.9, 0.76) | 28 | 7.7 × 103 | 1.5 × 10−7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xuan, L.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, J. Dynamics of h-Shaped Pulse to GHz Harmonic State in a Mode-Locked Fiber Laser. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121358

Wang L, Hu G, Wang Y, Chen G, Xuan L, Zhou Z, Yu J. Dynamics of h-Shaped Pulse to GHz Harmonic State in a Mode-Locked Fiber Laser. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121358

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lin, Guoqing Hu, Yan Wang, Guangwei Chen, Liang Xuan, Zhehai Zhou, and Jun Yu. 2025. "Dynamics of h-Shaped Pulse to GHz Harmonic State in a Mode-Locked Fiber Laser" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121358

APA StyleWang, L., Hu, G., Wang, Y., Chen, G., Xuan, L., Zhou, Z., & Yu, J. (2025). Dynamics of h-Shaped Pulse to GHz Harmonic State in a Mode-Locked Fiber Laser. Micromachines, 16(12), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121358