The Principle and Development of Optical Maskless Lithography Based Digital Micromirror Device (DMD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief History of DMD-Based Maskless Lithography

3. System and Principle of DMD-Based Maskless Lithography

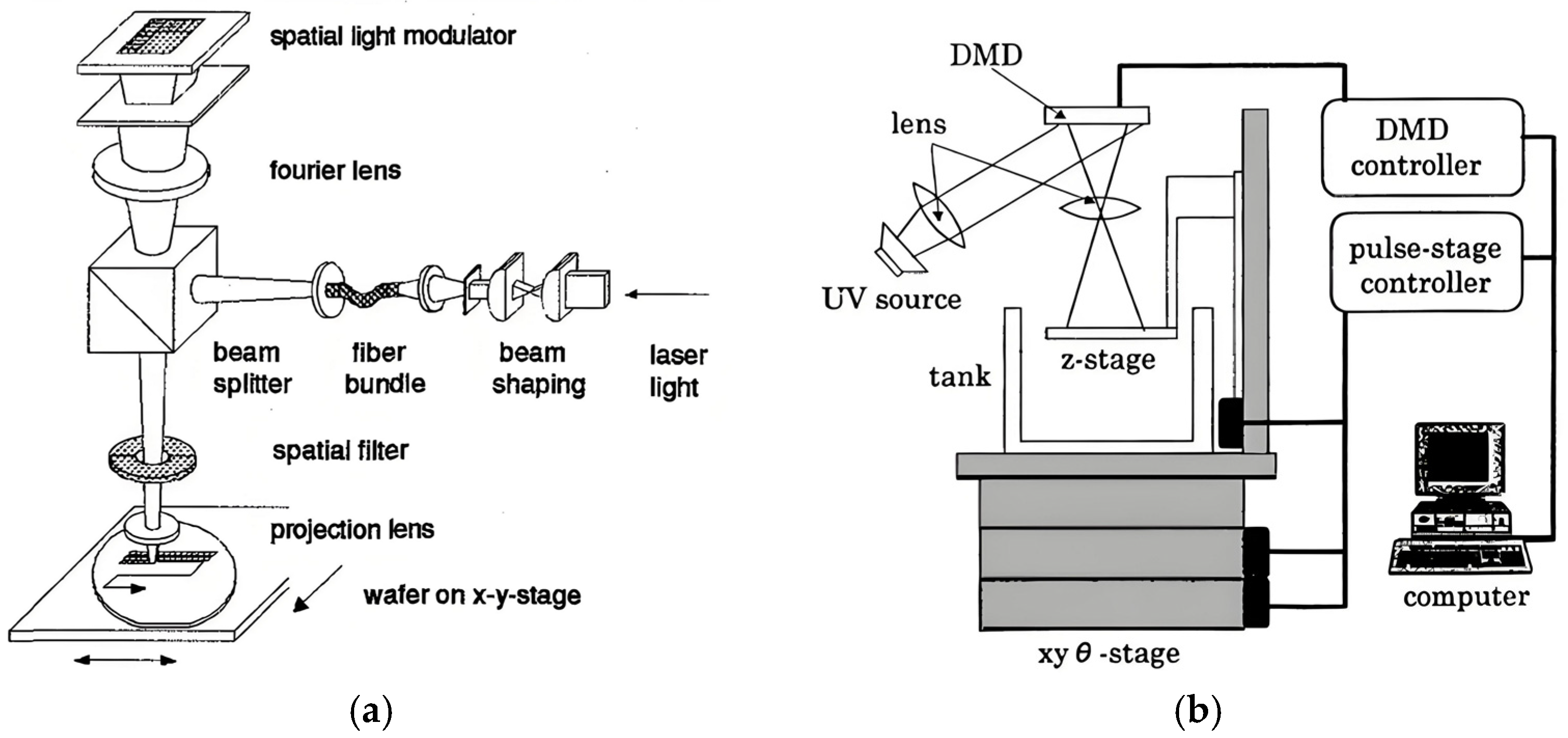

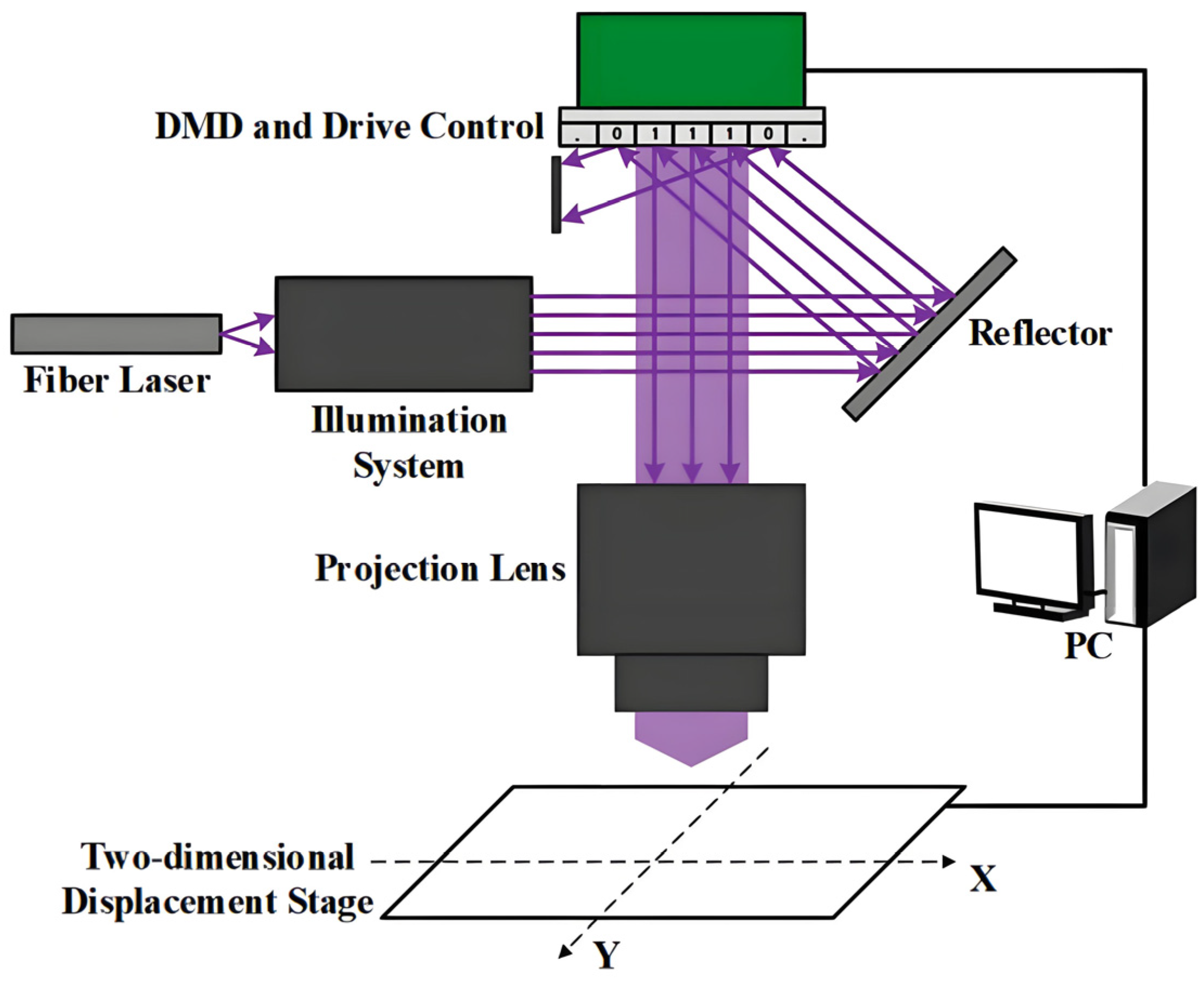

3.1. System Overview

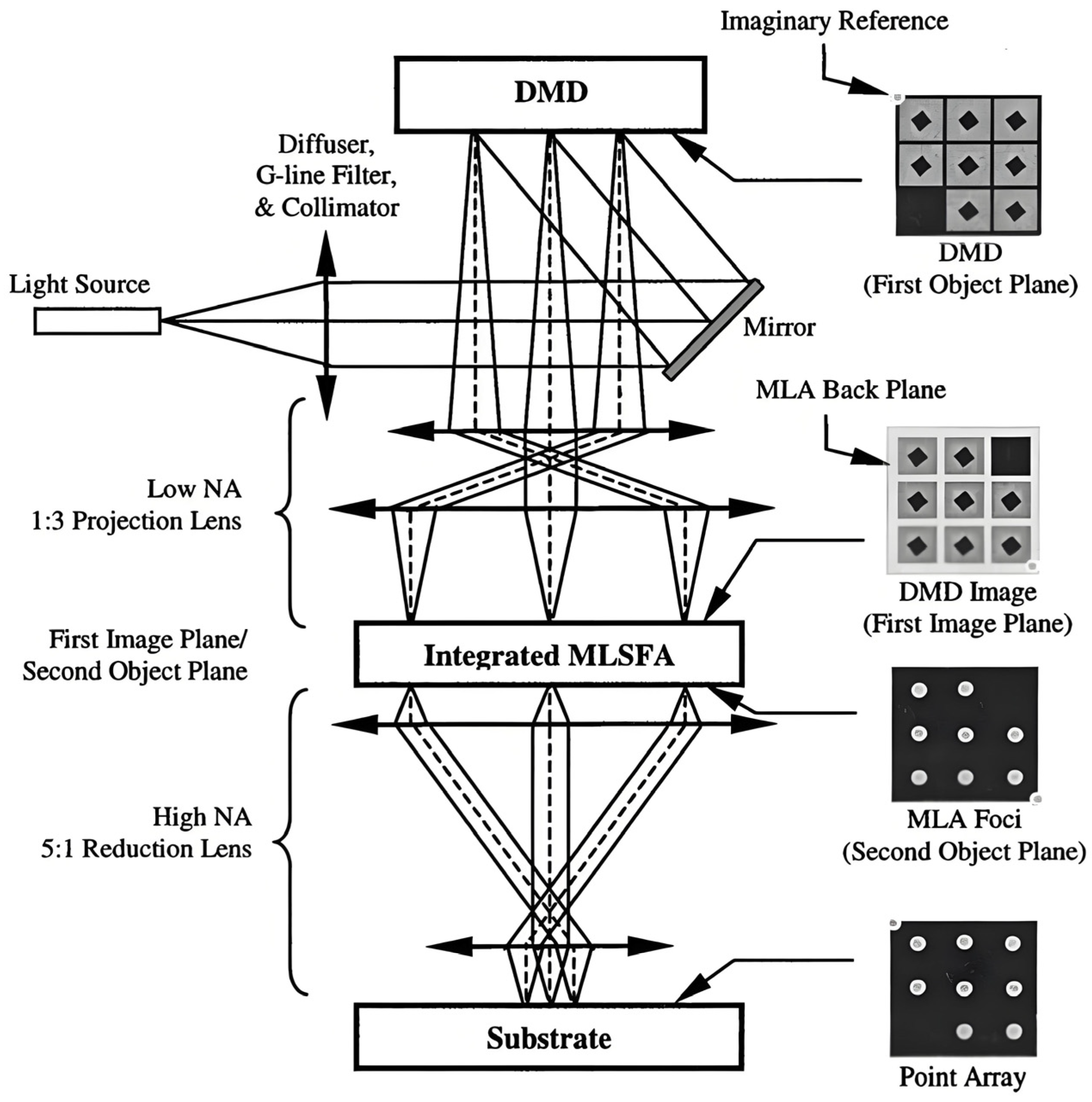

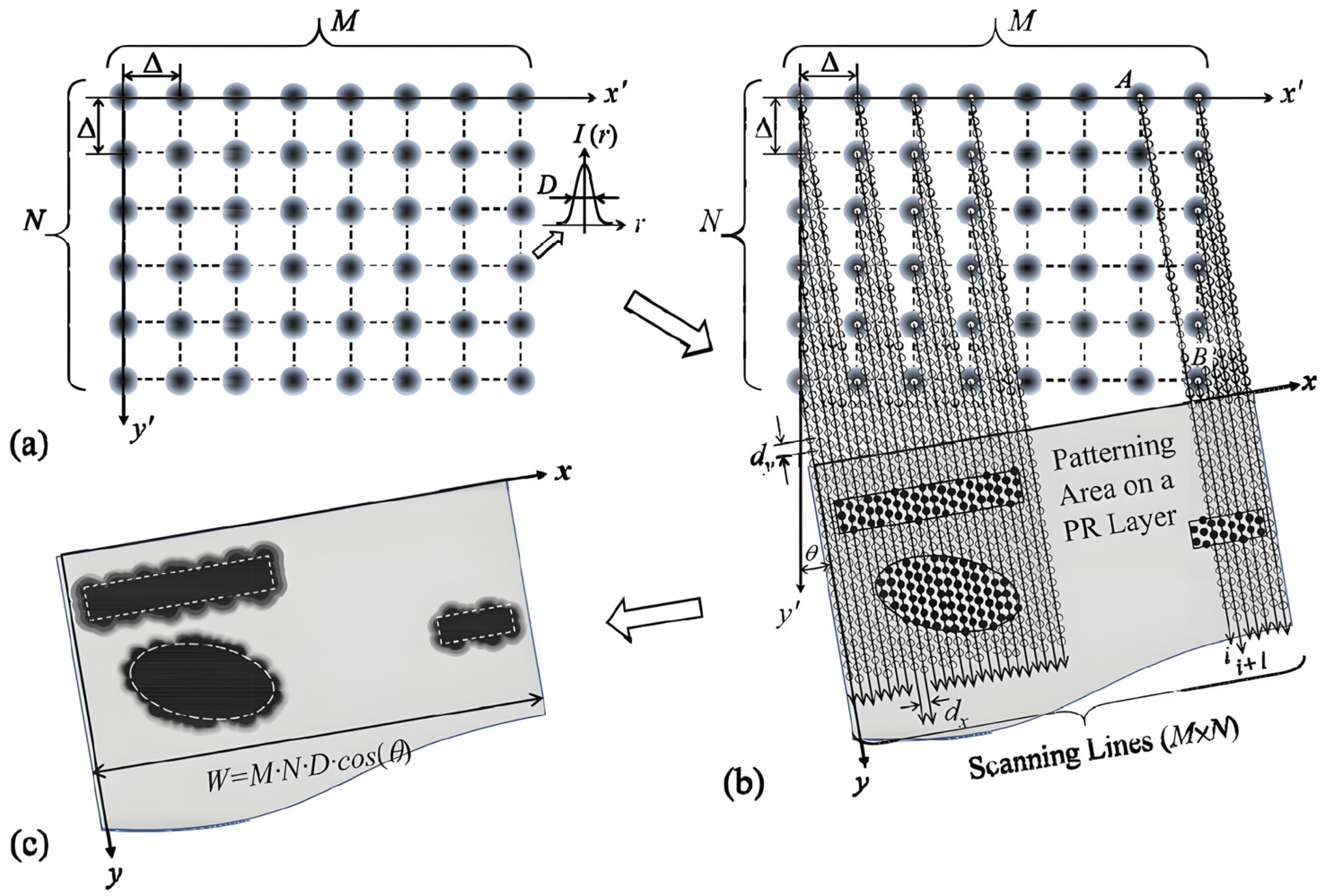

3.2. Point Array Generation

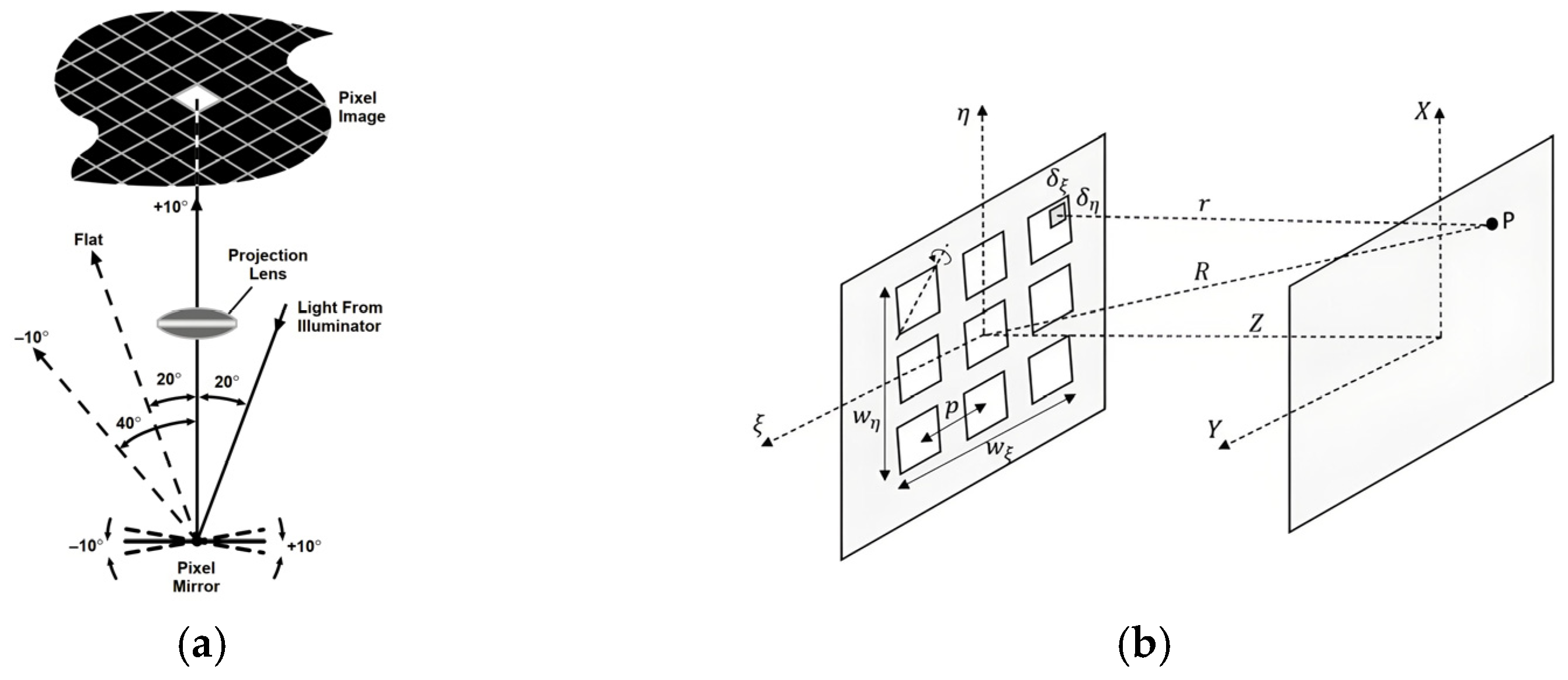

3.3. The Operation Principle

3.4. DMD and System Imaging Model

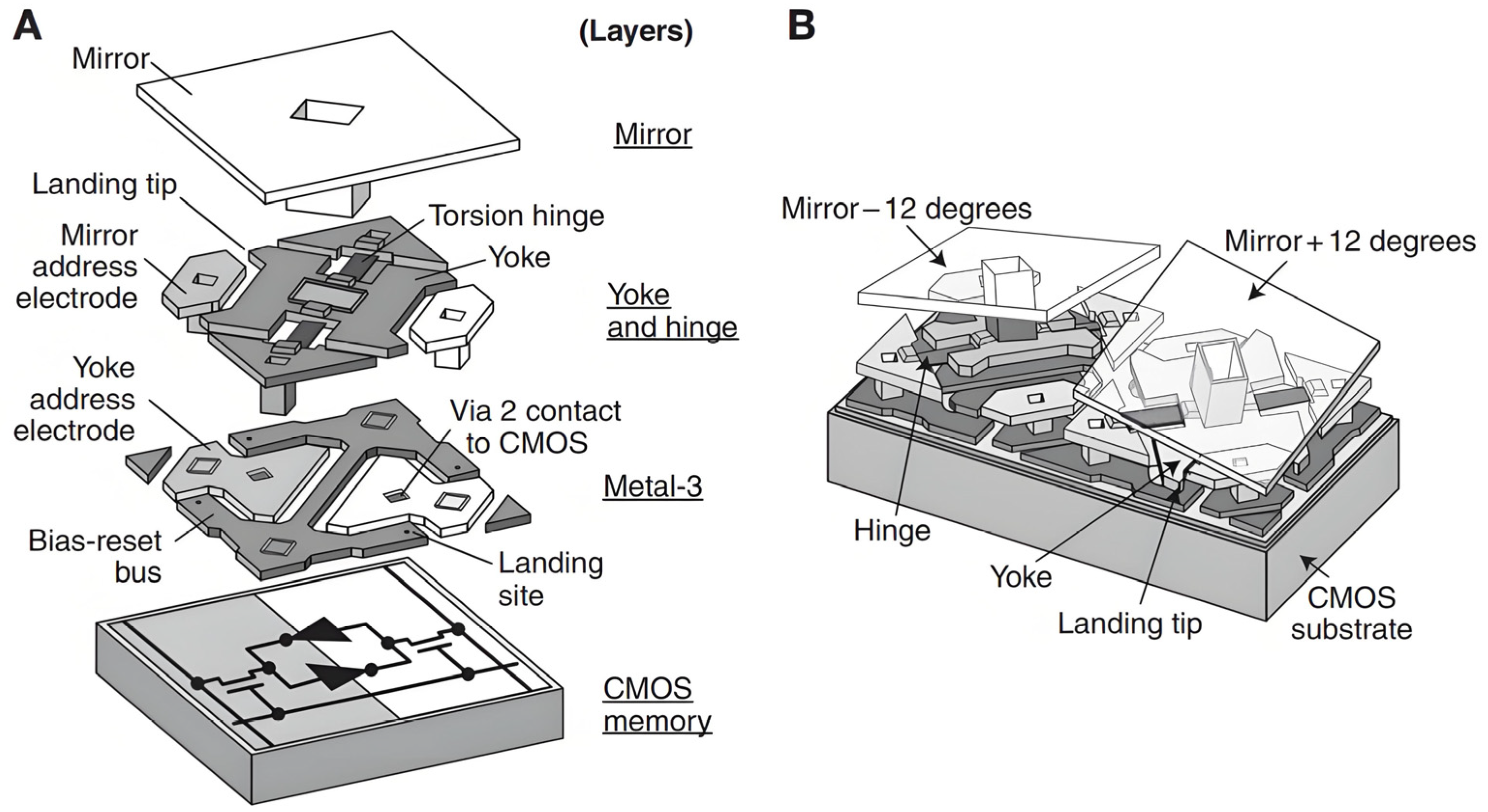

3.4.1. DMD and Characterizations

3.4.2. Imaging Model

3.5. Exposure Model

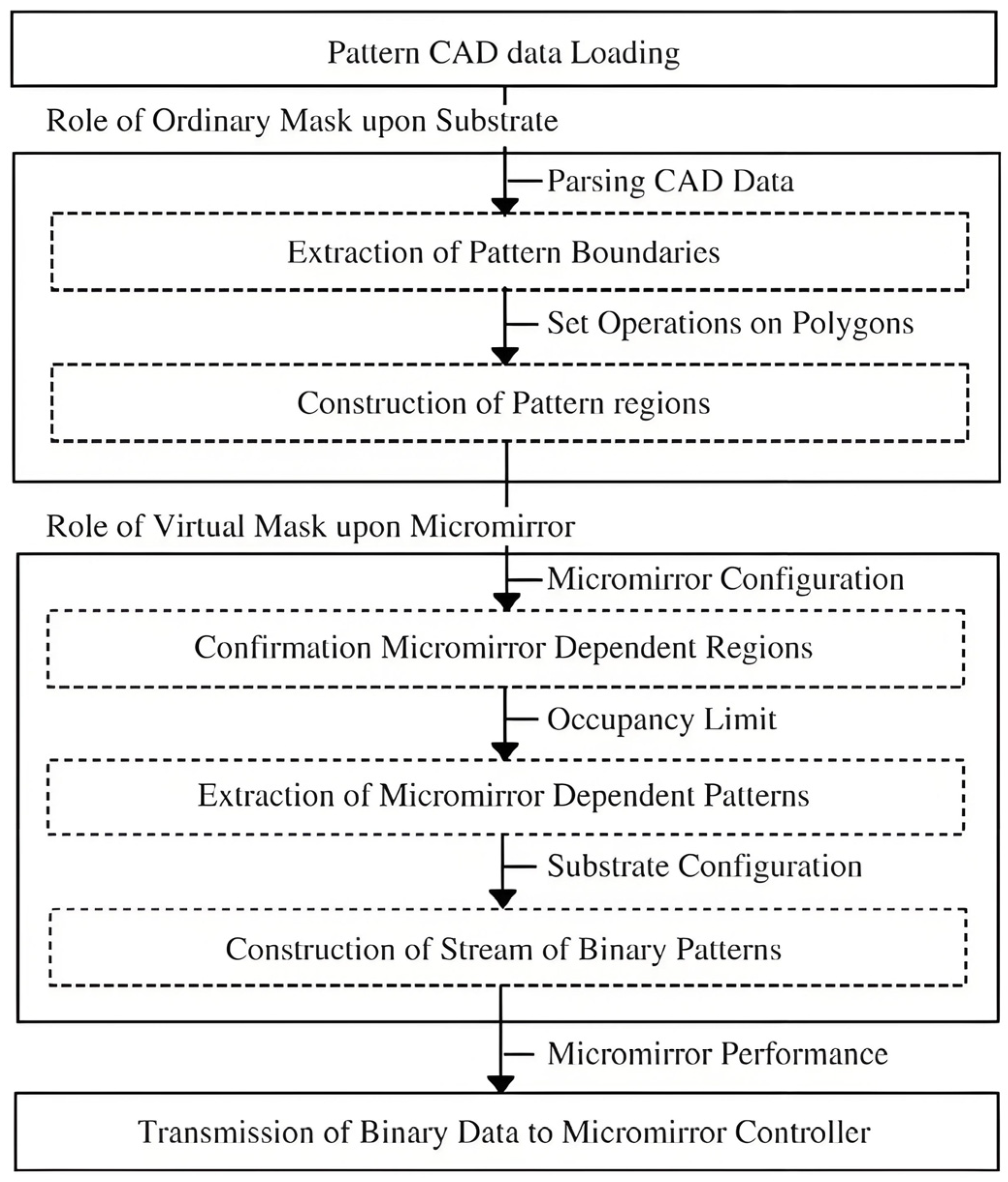

3.6. Digital Pattern Generation

4. The Recent Progress

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, B.J. Optical Lithography: Here Is Why, 2nd ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, R.; Patel, A.; Gil, D.; Smith, H.I. Maskless lithography. Mater. Today 2005, 8, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Klenk, D. Development of MOEMS technology in maskless lithography. In Proceedings of the Emerging Digital Micromirror Device Based Systems and Applications; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009; pp. 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, T.; Pickard, D.; Rafferty, B.; Crosland, N.; Adam, D.; Schubert, G. Maskless electron beam lithography: Prospects, progress, and challenges. Microelectron. Eng. 2002, 61, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yuan, D.; Das, S. Large-area microlens arrays fabricated on flexible polycarbonate sheets via single-step laser interference ablation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2010, 21, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.I.; Menon, R.; Patel, A.; Chao, D.; Walsh, M.; Barbastathis, G. Zone-plate-array lithography: A low-cost complement or competitor to scanning-electron-beam lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2006, 83, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.; Menon, R.; Carter, D.; Smith, H.I. Lithographic patterning and confocal imaging with zone plates. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2000, 18, 2881–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Setoyama, J. A UV-exposure system using DMD. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 2000, 83, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.F.; Feng, Z.; Yang, R.; Mei, W. High-resolution maskless lithography by the integration of micro-optics and point array technique. In Proceedings of the MOEMS Display and Imaging Systems; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, K.J.; Gao, Y.Q.; Li, F. Maskless lithography based on DMD. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 552, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D.; Duncan, W.M.; Slaughter, J. Emerging digital micromirror device (DMD) applications. In Proceedings of the MOEMS Display and Imaging Systems; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2003; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.F.; Feng, Z.; Yang, R.; Ishikawa, A.; Mei, W. High-resolution maskless lithography. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2003, 2, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Yang, J. A rasterization method for generating exposure pattern images with optical maskless lithography. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 2209–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J.H.; Cambron, S.D.; Walsh, K.M.; McNamara, S. Maskless grayscale lithography using a positive-tone photodefinable polyimide for MEMS applications. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2011, 20, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Luo, N.; Zhang, W. Fabrication of continuous relief micro-optic elements using real-time maskless lithography technique based on DMD. Opt. Laser Technol. 2014, 56, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chan, K.F.; Feng, Z.; Akihito, I.; Mei, W. Design and fabrication of microlens and spatial filter array by self-alignment for maskless lithography systems. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2003, 2, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.-H.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.-E.; Han, S.; Lee, H.-S.; Kwon, S.; Park, W. Fine-tuned grayscale optofluidic maskless lithography for three-dimensional freeform shape microstructure fabrication. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 5162–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldbaur, A.; Waterkotte, B.; Schmitz, K.; Rapp, B.E. Maskless projection lithography for the fast and flexible generation of grayscale protein patterns. Small 2012, 8, 1570–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Wang, K.; Gui, K.; Guo, H.; Zhuang, S. Parallel detection experiment of fluorescence confocal microscopy using DMD. Scanning 2016, 38, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammohan, A.; Dwivedi, P.K.; Martinez-Duarte, R.; Katepalli, H.; Madou, M.J.; Sharma, A. One-step maskless grayscale lithography for the fabrication of 3-dimensional structures in SU-8. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 153, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansotte, E.J.; Carignan, E.C.; Meisburger, W.D. High speed maskless lithography of printed circuit boards using digital micromirrors. In Proceedings of the Emerging Digital Micromirror Device Based Systems and Applications III; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barbucha, R.; Mizeraczyk, J. Recent progress in direct exposure of interconnects on PCBs. Circuit World 2016, 42, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Liou, W.-T.; Jung, C.-W.; Chen, G.; Ho, J.-C.; Chen, J.; Lee, C.-C. P-178: Flexible AMOLED Display Fabricated by Mask-less Digital Lithography Technology. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2019, 50, 1903–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Yi, J.; Cho, S.-H.; Kang, N.-H.; Cho, M.-W.; Shin, B.-S.; Choi, B. SLM-based maskless lithography for TFT-LCD. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 7835–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltmann, R.; Doleschal, W.; Gehner, A.; Kück, H.; Melcher, R.; Paufler, J.; Zimmer, G. New system for fast submicron optical direct writing. Microelectron. Eng. 1996, 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, L.; Deparnay, A.; Maschke, G.; Längle, M.; Brunner, R. MOEMS-based lithography for the fabrication of micro-optical components. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2005, 4, 041601–041605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fang, N.; Wu, D.; Zhang, X. Projection micro-stereolithography using digital micro-mirror dynamic mask. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2005, 121, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Kim, H. Delta lithography method to increase CD uniformity and throughput of SLM-based maskless lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2010, 87, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, W.; Takeshita, T.; Peng, Y.; Ogino, H.; Shibata, H.; Kudo, Y.; Maeda, R.; Sawada, R. Maskless lithographic fine patterning on deeply etched or slanted surfaces, and grayscale lithography, using newly developed digital mirror device lithography equipment. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 51, 06FB05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumpuang, S.; Hara, S. A MOSFET fabrication using a maskless lithography system in clean-localized environment of minimal fab. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2015, 28, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, S. The next generation of maskless lithography. In Proceedings of the Emerging Digital Micromirror Device Based Systems and Applications VIII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; p. 976102. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Han, C.; Jeon, H. Submicrometer-scale pattern generation via maskless digital photolithography. Optica 2020, 7, 1788–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Lu, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, J. Lithographic pattern quality enhancement of DMD lithography with spatiotemporal modulated technology. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Dong, X.-Z.; Guo, M.; Jin, F.; Wang, T.-W.; Duan, X.-M.; Zhao, Z.-S.; Zheng, M.-L. Achieving narrow gaps in micro-nano structures fabricated by maskless optical projection lithography. Appl. Phys. Express 2023, 16, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syu, Y.-S.; Huang, Y.-B.; Jiang, M.-Z.; Wu, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Maskless lithography for large area patterning of three-dimensional microstructures with application on a light guiding plate. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 12232–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Zemel, M.; Klosner, M. Large-area high-resolution lithography and photoablation systems for microelectronics and optoelectronics fabrication. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1681–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Kanatake, T.; Ishikawa, A. Moving Exposure System and Method for Maskless Lithography System. U.S. Patent 6379867B1, 30 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, W. Point Array Maskless Lithography. U.S. Patent 6473237B2, 29 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, H.; Kang, D.W.; Hahn, J.W. Analysis of the line pattern width and exposure efficiency in maskless lithography using a digital micromirror device. Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 3145–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.; Kang, D.W.; Song, Y.-T.; Hahn, J.W. Experimental analysis of pattern line width in digital maskless lithography. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2012, 11, 023004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G.; Lee, W.-S.; Chang, W.S.; Yoo, H. Method for improving the speed and pattern quality of a DMD maskless lithography system using a pulse exposure method. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 22487–22500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstrom, T.; Bleeker, A.; Hintersteiner, J.; Troost, K.; Freyer, J.; van der Mast, K. OML: Optical maskless lithography for economic design prototyping and small-volume production. In Proceedings of the Optical Microlithography XVII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; pp. 777–787. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D.; Gemmink, J.W.; Pain, L.; Postnikov, S.V. Status and future of maskless lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2006, 83, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Sun, Q.; Shi, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Weng, Z.; Xu, J. Method for improving illumination uniformity of a digital mask-less scanning lithography system. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 185, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosner, M.; Jain, K. Massively parallel, large-area maskless lithography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 2880–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.-L.; Wu, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. Enhanced corner sharpness in DMD-based scanning maskless lithography using optical proximity correction and genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 45357–45372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-F.; Wu, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-C. High performance DMD lithography based on oblique scanning, pulse lighting, and optical distortion calibration. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 183, 112388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, D.-H.; Chien, H.-L.; Lee, Y.-C. Maskless lithography based on digital micromirror device (DMD) and double sided microlens and spatial filter array. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 113, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.L.; Chiu, Y.H.; Lee, Y.C. Maskless lithography based on oblique scanning of point array with digital distortion correction. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2021, 136, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miau, T.-H.; Lee, Y.-C. Optimization of pattern quality in DMD scanning maskless lithography: A parametric study of the OS3L exposure algorithm. Microelectron. Eng. 2025, 298, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, V.; Saggau, P. Digital micromirror devices: Principles and applications in imaging. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013, 2013, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Mehrl, D. Characterization of the digital micromirror devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2014, 61, 4210–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Abreu, M.; Cabral, A.; Rebordão, J. Characterization of light diffraction by a digital micromirror device. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2407, 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Wong, K.S. Manipulating spatial light fields for micro-and nano-photonics. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2012, 44, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Kim, H. Influence of dynamic sub-pixelation on exposure intensity distribution under diffraction effects in spatial light modulation based lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2012, 98, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Dong, X.-Z.; Zheng, M.-L.; Jin, F.; Liu, J.; Duan, X.-M.; Zhao, Z.-S. Multi-scale structure patterning by digital-mask projective lithography with an alterable projective scaling system. Aip Adv. 2018, 8, 065317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, L.; Luo, N.; Chen, T.; Sun, C.; Chen, M. Research on improving the transverse resolution of binary optical element by digital-division-mask technique. Optik 2010, 121, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Tan, M.; Liu, M.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, R.; Liu, H. Technology of static oblique lithography used to improve the fidelity of lithography pattern based on DMD projection lithography. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 157, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-F.; Huang, Y.-J. Resolution enhancement using pulse width modulation in digital micromirror device-based point-array scanning pattern exposure. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2016, 79, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Deng, Q.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hu, S. Dose-modulated maskless lithography for the efficient fabrication of compound eyes with enlarged field-of-view. IEEE Photonics J. 2019, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, G. Linewidth control by overexposure in laser lithography. Opt. Appl. 2008, 38, 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-T.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Guo, X.; Duan, X.-M. Deep learning-driven digital inverse lithography technology for DMD-based maskless projection lithography. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 180, 111578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Pu, D.-l.; Chen, L.-s. The research of micro–nano laser patterning system based on digital micromirror device. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N J. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 2014, 228, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Du, J.; Guo, Y.; Du, C.; Cui, Z.; Yao, J. Simulation of DOE fabrication using DMD-based gray-tone lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2006, 83, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wu, S.-Y.; Kohn Jr, R.N.; Becker, M.F.; Heinzen, D. Grayscale laser image formation using a programmable binary mask. Opt. Eng. 2012, 51, 108201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, X.; Gao, F.; Luo, B.; Duan, X.; Du, J.; Qiu, C. Imaging simulation of maskless lithography using a DMD. In Proceedings of the Advanced Microlithography Technologies; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2005; pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, H.; Tan, X.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.; Song, L.; Wang, Z. Diffraction analysis of digital micromirror device in maskless photolithography system. J. Micro/Nanolithogr. MEMS MOEMS 2014, 13, 043016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, H.; Kang, D.W.; Hahn, J.W. Analysis of the effective reflectance of digital micromirror devices and process parameters for maskless photolithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lu, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Wu, G.; Liu, C.; Liu, H. Measurement and compensation of a stitching error in a DMD-based step-stitching photolithography system. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 9074–9081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Jing, X.; Liao, N. Design method for the high optical efficiency and uniformity illumination system of the projector. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 12502–12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ren, B.; Tang, Y.; Wu, D.; Pan, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, J. Method for improving pattern quality of digital lithography system using curvature blur dynamic exposure technique. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 187, 112839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lin, J.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wen, S.; Yin, Y.; Lan, C.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Genetic algorithm-based optical proximity correction for DMD maskless lithography. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 23598–23607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, Y.; Ren, B.; Wu, D.; Pan, J.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, J. DMD digital lithography optimization based on a hybrid genetic algorithm and improved exposure model. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 30407–30418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Li, J. Edge smoothness enhancement in DMD scanning lithography system based on a wobulation technique. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 21958–21968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, L.; Wang, B.; Wen, K.; Lei, L. Simulation of the effect of incline incident angle in DMD maskless lithography. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 844, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, L.J. Digital light processing for high-brightness high-resolution applications. In Proceedings of the Projection Displays III; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1997; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, H.H. On the diffraction theory of optical images. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1953, 217, 408–432. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Kim, H. Spatial light modulation based 3D lithography with single scan virtual layering. Microelectron. Eng. 2011, 88, 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, F.H.; Neureuther, A.R.; Tuttle, J.A.; Walker, E.J. Modeling projection printing of positive photoresists. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1975, 22, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Jones, D.; Lopez, G. Comprehensive modeling of the lithographic errors in laser direct write. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2019, 37, 061603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-F.; Huang, Q.-A. Comprehensive simulations for ultraviolet lithography process of thick SU-8 photoresist. Micromachines 2018, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Du, J.; Duan, X.; Luo, B.; Tang, X.; Guo, Y.; Cui, Z.; Du, C.; Yao, J. Enhanced dill exposure model for thick photoresist lithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2005, 78, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Yang, J.; Du, J.; Guo, Y.; Du, C. Simulation of optical lithography process for fabricating diffractive optics. In Proceedings of the Holography, Diffractive Optics, and Applications; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2002; pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Onanuga, T.; Erdmann, A. 3D simulation of light exposure and resist effects in laser direct write lithography. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices (SISPAD), Nuremberg, Germany, 6–8 September 2016; pp. 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Yang, X.; Gao, F.; Guo, Y. Simulation and analysis for microstructure profile of optical lithography based on SU-8 thick resist. Microelectron. Eng. 2007, 84, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Park, K.; Kim, H.; Seo, M. Lithographic data generation algorithm based on micromirror cell decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2006 SICE-ICASE International Joint Conference, Busan, Republic of Korea, 18–21 October 2006; pp. 2179–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Lee, T.; Kim, H. Parameters affecting pattern fidelity and line edge roughness under diffraction effects in optical maskless lithography using a digital micromirror device. In Proceedings of the Optical Design and Testing V; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; pp. 454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kanatake, T. High Resolution Point Array. U.S. Patent 6870604, 22 March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, K.; Quenzer, H.J.; Jürss, M.; Wagner, B. Micro-optic fabrication using one-level gray-tone lithography. In Proceedings of the Miniaturized Systems with Micro-Optics and Micromechanics II; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1997; pp. 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Cheng, D. P-9.8: Design Method of LCoS Projection System Based on Multiplexing of Imaging and Illumination Optical Paths. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2024, 55, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Q.; Wang, P.Q.; Shi, Z.J.; Luo, N.N. Research and Design on Digital Mask Lithography Control System. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 416, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Kim, H. Lithography upon micromirrors. Comput.-Aided Des. 2007, 39, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Park, K.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.; An, C.; Seo, M. Region-based Pattern Generating System for Maskless Photolithography. Inst. Control Robot. Syst. 2005, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Song, J.; An, C. Region-based pattern generation scheme for DMD based maskless lithography. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Graphics Recognition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Kim, H.; Park, M. Maskless lithographic pattern generation system upon micromirrors. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 2006, 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jin, Y.; Kim, H.; Seo, M. Proposal of Distributed Architecture for Micromirror Image Generation in Maskless Optolithography System. In Proceedings of the 2006 SICE-ICASE International Joint Conference, Busan, Republic of Korea, 18–21 October 2006; pp. 662–666. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Jin, F.; Dong, X.-Z.; Zheng, M.-L.; Zhao, Z.-S.; Duan, X.-M. λ/12 super resolution achieved in maskless optical projection nanolithography for efficient cross-scale patterning. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 3915–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-H.R.; Vijaya Kumar, B.; Sankaranarayanan, A.C. 2^16 shades of gray: High bit-depth projection using light intensity control. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 27937–27950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, H.; Hyun, B.-R.; Xu, K.; Kwok, H.-S.; Liu, Z. High-power AlGaN deep-ultraviolet micro-light-emitting diode displays for maskless photolithography. Nat. Photonics 2025, 19, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ren, B.; Tang, Y.; Wu, D.; Pan, J.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, J. Edge smoothing optimization method in DMD digital lithography system based on dynamic blur matching pixel overlap technique. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 2114–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, N.; Chen, D. Edge smoothness enhancement of digital lithography based on the DMDs collaborative modulation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2024, 34, 075011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ma, X.; Zhang, S.; Lin, M.; Porras-Díaz, N.; Arce, G.R. Block-based inverse lithography technology with adaptive level-set algorithm. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 182, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, D.; Pan, J.; Shao, Y.; He, S. Dynamic diversity-driven hierarchical PSO method for edge distortion compensation in digital lithography mask optimization. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 196, 109379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.; Lee, Y. Three dimensional maskless ultraviolet exposure system based on digital light processing. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2020, 21, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Su, Y.; Wang, F.; Liang, Y. A flexible self-calibration method for large-stroke motion stage by using the multi-region stitching strategy based on least square algorithm. Appl. Phys. Express 2020, 13, 056501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Su, Y.; Liang, Y. Precise fabrication of large-area microstructures by digital oblique scanning lithography strategy and stage self-calibration technique. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 096501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.W.; Kang, M.; Hahn, J.W. Keystone error analysis of projection optics in a maskless lithography system. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 16, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-K.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.-L.; Xu, J.; Li, J.-H. Analysis and correction of the distortion error in a DMD based scanning lithography system. Opt. Commun. 2019, 434, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Zhao, S.; Cong, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Y.; Liu, H. Ultra-pixel precision correction method for maskless lithography projection distortion. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 39208–39221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkubo, A.; Chu, J.; Lee, J.; Cho, S.; Joo, W.; Bae, S. On-machine laser spot diagnostics by scanning linear image sensor for maskless lithography system. In Proceedings of the Optical Manufacturing and Testing XIV; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; pp. 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Miau, T.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Lee, Y.C. High-precision alignment system for DMD-based maskless lithography in multilayer exposure applications. Precis. Eng. 2025, 96, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, T.; Jiang, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, H. Path planning of pattern transfer based on dual-operator and a dual-population ant colony algorithm for digital mask projection lithography. Entropy 2020, 22, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingzhi, W.; Tailin, H.; Xu, J.; Yuhan, Y.; Jun, H. Application of Improved Genetic Algorithm in Path Planning of Step DMD Digital Mask Lithography. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 27–29 June 2020; pp. 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.P.; Qu, X.; Soman, P.; Hribar, K.C.; Lee, J.W.; Chen, S.; He, S. Rapid fabrication of complex 3D extracellular microenvironments by dynamic optical projection stereolithography. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblich, M.; Kraus, M.; Stumpf, D.; Werner, L.; Hillmer, H.; Brunner, R. Variable ring-shaped lithography for the fabrication of meso-and microscale binary optical elements. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 2049–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Cao, J.; Zhao, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, R.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H. Cross-scale and cross-precision structures/systems fabricated by high-efficiency and low-cost hybrid 3D printing technology. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariwala, A.S.; Schwerzel, R.E.; Nikoue, H.A.; Rosen, D.W. Exposure controlled projection lithography for microlens fabrication. In Proceedings of the Advanced Fabrication Technologies for Micro/Nano Optics and Photonics V; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; pp. 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.H.; Kwatra, A.; Jariwala, A.S.; Rosen, D.W. Real-Time Selective Monitoring of Exposure Controlled Projection Lithography; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, K.; Nakai, K.; Matsui, H.; Nagao, T.; Norimitsu, Y. Novel exposure system for FOWLP and MCM photolithopraphy process. In Proceedings of the IEEE CPMT Symposium Japan 2014, Kyoto, Japan, 4–6 November 2014; pp. 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, F.-L.; Kahle, R.; Kunz, M.; Kunz, T.; Kossev, J.; Müller, T.; Pentz, M.; Dietterle, M.; Ostmann, A. Process modules for high-density interconnects in panel-level packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 10, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.K. Evolution of maskless digital lithography: Game changer for advanced semiconductor packaging. MR Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, C.; Lee, H.-N.; Kim, C.K. Development of photolithography process for printed circuit board using liquid crystal mask in place of photomask. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 51, 09MF16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-W. Maskless lithography laser source target light dose reversed mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Computer Symposium (ICS), Tainan, Taiwan, 17–19 December 2020; pp. 330–334. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, N.; Xiao, H.; Ma, L.; Meng, Q. A low-cost digital lithography system supporting visual focusing and its application on optical fiber. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 16th International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS), Xiamen, China, 25–29 April 2021; pp. 563–566. [Google Scholar]

- Galiullin, A.A.; Pugachev, M.V.; Duleba, A.I.; Kuntsevich, A.Y. Cost-Effective Laboratory Matrix Projection Micro-Lithography System. Micromachines 2023, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.K.; Raunio, J.-P.; Karjalainen, M.T.; Ryynänen, T.; Lekkala, J. Novel method for intensity correction using a simple maskless lithography device. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2013, 194, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Nagao, T.; Norimitsu, Y.; Majima, S. Laser based direct exposure to photo materials used in advanced semiconductor packaging. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2018, 31, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal, S.L.; Cirino, G.A.; Montagnoli, A.N.; Sobrinho, A.A.; Rubert, J.B.; Hospital, M.; Mansano, R.D. Microlens array fabricated by a low-cost grayscale lithography maskless system. Opt. Eng. 2013, 52, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, M.; Qiu, J.; Ye, H. Fabrication of high fill-factor aspheric microlens array by dose-modulated lithography and low temperature thermal reflow. Microsyst. Technol. 2018, 25, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Moon, S.K.; Seo, M. Hybrid layering scanning-projection micro-stereolithography for fabrication of conical microlens array and hollow microneedle array. Microelectron. Eng. 2016, 153, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirino, G.; Amaral, F.; Lopera, S.; Montagnolil, A.; Arruda, A.; Mansano, R.; Monteiro, D. Wavefront sensor sampling plane fabricated by maskless grayscale lithography. In Proceedings of the Micro-Optics 2014; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Liu, C.; Huang, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, R.; Lu, Z. DMD maskless digital lithography based on stepwise rotary stitching. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2023, 33, 045003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faniayeu, I.; Mizeikis, V. Vertical split-ring resonator perfect absorber metamaterial for IR frequencies realized via femtosecond direct laser writing. Appl. Phys. Express 2017, 10, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Lachmayer, R.; Roth, B. Maskless lithography for versatile and low cost fabrication of polymer based micro optical structures. OSA Contin. 2020, 3, 2808–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L. Development of multi-dimensional cell co-culture via a novel microfluidic chip fabricated by DMD-based optical projection lithography. IEEE Trans. Nanobioscience 2019, 18, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.; Park, W. Microsized 3D hydrogel printing system using microfluidic maskless lithography and single axis stepper motor. BioChip J. 2020, 14, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, F.; Mao, H.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, J.; Wang, L.; Malmstadt, N.; Chen, Y. In-situ transfer vat photopolymerization for transparent microfluidic device fabrication. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Critical Stage | Time Period | Representative Work | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Inception | 1996–2000 | - Seltmann et al. (1996): Submicron optical direct-write system based on programmable SLM [25]. - Takahi & Setoyama (2000): First application of DMD in UV exposure [8]. | - Verified ML’s microfabrication potential. - Laid the foundation for DMD-based ML by solving early SLM cost and flexibility issues. |

| Performance Breakthrough | 2003–2005 | - Chan et al. (2003): High-resolution ML system with TI’s SVGA DMD [9,12]. - Yang et al. (2003): MLSFA-integrated system for noise reduction [16]. - Erdmann et al. (2005): DMD as switchable mask for parallel processing [26]. - Sun et al. (2005): DMD-based projection micro-stereolithography (PmSL) [27]. | - Significantly improved resolution (down to 1.5 μm L/S). - Realized parallel processing and expanded ML to 3D microfabrication. |

| Industrial Adaptation | 2009–2012 | - Kim et al. (2009): DMD-based ML for TFT-LCD manufacturing [24]. - Seo & Kim (2010): Delta lithography method (DLM) for CD uniformity [28]. - Hansotte et al. (2011): Gray-level DMD tech for PCB lithography [21]. - Iwasaki et al. (2012): Dual-lens DMD system for uneven substrates [29]. | - Adapted ML to high-volume industries (TFT-LCD, PCB, MEMS). - Transformed ML from a lab tool to an industrial-grade technology. |

| Cost and Efficiency Optimization | 2014–2019 | - Khumpuang et al. (2015): “Minimal fab” with DLP-based ML [30]. - Diez (2016): Next-generation Maskless Aligner (MLA) [31]. - Lee et al. (2018): GPU-accelerated rasterization for data processing [13]. | - Reduced application costs (no full cleanroom required). - Broke through high-volume production bottlenecks, expanding ML’s adoption. |

| Cutting-Edge Expansion | 2020–Present | - Kang et al. (2020): 180 nm line width with 200× objective [32]. - Guo et al. (2021): Spatiotemporal modulation (STPL) for ultra-high fidelity [33]. - Liu et al. (2023): Femtosecond laser ML for 243 nm gaps [34]. - Syu et al. (2023): Large-area 3D patterning for advanced displays [35]. | - Pushed ML to submicron/nanoscale resolution. - Expanded ML to cutting-edge fields (nanophotonics, advanced displays). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Cui, G.; Xu, G. The Principle and Development of Optical Maskless Lithography Based Digital Micromirror Device (DMD). Micromachines 2025, 16, 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121356

Li X, Cui G, Xu G. The Principle and Development of Optical Maskless Lithography Based Digital Micromirror Device (DMD). Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121356

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xianjie, Guodong Cui, and Guili Xu. 2025. "The Principle and Development of Optical Maskless Lithography Based Digital Micromirror Device (DMD)" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121356

APA StyleLi, X., Cui, G., & Xu, G. (2025). The Principle and Development of Optical Maskless Lithography Based Digital Micromirror Device (DMD). Micromachines, 16(12), 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121356