Assessing Kidney Injury Biomarkers and OTA Exposure in Urine of Lebanese Adolescents Amid Economic Crisis and Evolving Dietary Patterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Population Characteristics

2.2. Food Groups Consumption and Comparison to Three Different Diets’ Recommendations

Food Groups Consumption

2.3. Dietary Exposure Analysis

2.4. Exposure and Renal Data

2.4.1. Mycotoxin Biomarkers

2.4.2. Kidney Injury Biomarkers

2.4.3. Renal Function Indicators

2.5. Correlations

2.6. Probable OTA Dietary Intake

2.7. Risk Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Design and Data Collection

5.2. Ethical Considerations

5.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

5.4. Data Collection

5.4.1. Sociodemographic, Medical, and Anthropometric Data

5.4.2. Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)

5.4.3. 24-Hour Recalls

5.4.4. Average Consumption

5.4.5. Food Contamination Data

5.4.6. Dietary Exposure Calculation

5.4.7. Urine Samples

5.5. Materials and Chemicals

5.6. ELISA Tests

5.6.1. Human Lipocalin-2 (NGAL)

5.6.2. Human Kim-1

5.6.3. N-Acetylglucosaminidase (Beta-NAG) Activity Assay (NAG)

5.7. HPLC Quantification of OTA and OTα

5.7.1. Samples Preparation

5.7.2. HPLC Analysis

5.8. Interpretation of OTA Exposure Risk

5.8.1. Probable Daily Intake

5.8.2. Margin of Exposure

5.8.3. Weekly Exposure to OTA

5.9. Interpretation of Kidney Injury Biomarkers Results

5.10. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marin, S.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V. Mycotoxins: Occurrence, Toxicology, and Exposure Assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlovsky, P.; Suman, M.; Berthiller, F.; De Meester, J.; Eisenbrand, G.; Perrin, I.; Oswald, I.P.; Speijers, G.; Chiodini, A.; Recker, T.; et al. Impact of food processing and detoxification treatments on mycotoxin contamination. Mycotoxin Res. 2016, 32, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, C.P.; Gong, Y.Y. Mycotoxins and human disease: A largely ignored global health issue. Carcinogenesis 2009, 31, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, E.; Schatzmayr, G.; Tassis, P.; Tzika, E.; Marin, D.; Taranu, I.; Tabuc, C.; Nicolau, A.; Aprodu, I.; Puel, O.; et al. Current Situation of Mycotoxin Contamination and Co-occurrence in Animal Feed—Focus on Europe. Toxins 2012, 4, 788–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Ochratoxin A: General Overview and Actual Molecular Status. Toxins 2010, 2, 461–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Toscano, P.; Van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Moretti, A.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Brera, C.; Rortais, A.; Goumperis, T.; Robinson, T. Aflatoxin B1 Contamination in Maize in Europe Increases Due to Climate Change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 12, 24328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A.; Manderville, R.A. Ochratoxin A: An overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 61–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. International Agency for Research on Cancer Iarc Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks To Humans. In Larc Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 80, pp. 27–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer-Rohr, I.; Schlatter, J.; Dietrich, D.R. Kinetic Parameters and Intraindividual Fluctuations of ochratoxin A plasma levels in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 2000, 74, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, V.S.; Ferguson, M.A.; Bonventre, J.V. Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 48, 463–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ráduly, Z.; Szabó, A.; Mézes, M.; Balatoni, I.; Price, R.G.; Dockrell, M.E.; Pócsi, I.; Csernoch, L. New perspectives in application of kidney biomarkers in mycotoxin induced nephrotoxicity, with a particular focus on domestic pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1085818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malir, F.; Ostry, V.; Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A.; Malir, J.; Toman, J. Ochratoxin A: 50 Years of Research. Toxins 2016, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, H.; Betbeder, A.-M.; Creppy, E.; Pallardy, M.; Azouri, H. Ochratoxin A Levels in Human Plasma and Foods in Lebanon. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubra, L.; Sarkis, D.; Hilan, C.; Verger, P. Occurrence of total aflatoxins, ochratoxin A and deoxynivalenol in foodstuffs available on the Lebanese market and their impact on dietary exposure of children and teenagers in Beirut. Food Addit. Contaminants. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2009, 26, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubrane, K.; EL Khoury, A.; Lteif, R.; Rizk, T.; Kallassy, M.; Hilan, C.; Maroun, R. Occurrence of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A in Lebanese cultivated wheat. Mycotoxin Res. 2011, 27, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, F.; Nasreddine, L.; Hilan, C.; Bartosik, M.; Parent-Massin, D. Dietary exposure to aflatoxins, ochratoxin A and deoxynivalenol from a total diet study in an adult urban Lebanese population. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 73, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubrane, K.; Mnayer, D.; El Khoury, A.; El Khoury, A.; Awad, E. Co-occurrence of Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and Ochratoxin A (OTA) in Lebanese stored wheat. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1547–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daou, R.; Joubrane, K.; Khabbaz, L.R.; Maroun, R.G.; Ismail, A.; El Khoury, A. Aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A in imported and Lebanese wheat and -products. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2021, 14, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.F.; Kordahi, R.; Dimassi, H.; El Khoury, A.; Daou, R.; Alwan, N.; Merhi, S.; Haddad, J.; Karam, L. Aflatoxin B1 in rice: Effects of storage duration, grain type and size, production site, and season. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives Ochratoxin A. Safety Evaluation of Certain Mycotoxins in Food; WHO Food Additives Series 47: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury, A.; Daou, R.; Atoui, A.; Hoteit, M. Mycotoxins in Lebanese Food Basket; Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth: Beirut, Lebanon, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Peredo, G.B.; Montaño-Castellón, I.; Gutiérrez-Peredo, A.J.; Lopes, M.B.; Tapioca, F.P.M.; Guimaraes, M.G.M.; Montaño-Castellón, S.; Guedes, S.A.; da Costa, F.P.M.; Mattoso, R.J.C.; et al. The urine protein/creatinine ratio as a reliable indicator of 24-h urine protein excretion across different levels of renal function and proteinuria: The TUNARI prospective study. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, A.; Boyer, O.; Hodson, E.; Bagga, A.; Gipson, D.S.; Samuel, S.; Wetzels, J.; Alhasan, K.; Banerjee, S.; Bhimma, R.; et al. IPNA clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 38, 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain; Schrenk, D.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.-C.; Nebbia, C.S.; et al. Risk Assessment of Ochratoxin A in Food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kőszegi, T.; Poór, M.; Manderville, R.A.; Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A. Ochratoxin A: Molecular Interactions, Mechanisms of Toxicity and Prevention at the Molecular Level. Toxins 2016, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresca, M.; Mahfoud, R.; Pfohl-Leszkowicz, A.; Fantini, J. The Mycotoxin Ochratoxin A Alters Intestinal Barrier and Absorption Functions but Has No Effect on Chloride Secretion. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2001, 176, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzinger, E.; Ziegler, K. Ochratoxin A from a toxicological perspective. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 23, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Dohnal, V.; Huang, L.; Kuca, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.; Yuan, Z. Metabolic Pathways of Ochratoxin A. Curr. Drug Metab. 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.-C.; Nebbia, C.S.; et al. Risks for animal health related to the presence of ochratoxin A (OTA) in feed. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrik, J.; Žanić-Grubišić, T.; Barišić, K.; Pepeljnjak, S.; Radić, B.; Ferenčić, Ž.; Čepelak, I. Apoptosis and oxidative stress induced by Ochratoxin A in rat kidney. Arch. Toxicol. 2004, 77, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, M.B.; Marin, S.; Tarragó, M.; Cano-Sancho, G.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V. Ochratoxin A and Its Metabolite Ochratoxin Alpha in Urine and Assessment of the Exposure of Inhabitants of Lleida, Spain. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Muñoz, K.; Degen, G. Ochratoxin A and Its Metabolites in Urines of German Adults—An Assessment of Variables in Biomarker Analysis. Toxicol Lett. 2017, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, M.; Faisal, Z.; Zand, A.; Bencsik, T.; Lemli, B.; Kunsági-Máté, S.; Szente, L. Removal of Zearalenone and Zearalenols from Aqueous Solutions Using Insoluble Beta-Cyclodextrin Bead Polymer. Toxins 2018, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, N.; Jutabha, P.; Endou, H. Molecular Mechanism of Ochratoxin A Transport in the Kidney. Toxins 2010, 2, 1381–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlender, V.; Breljak, D.; Ljubojević, M.; Flajs, D.; Balen, D.; Brzica, H.; Domijan, A.-M.; Peraica, M.; Fuchs, R.; Anzai, N.; et al. Low doses of Ochratoxin A upregulate the protein expression of organic anion transporters Oat1, Oat2, Oat3 and Oat5 in rat kidney cortex. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 239, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ráduly, Z.; Price, R.G.; Dockrell, M.E.C.; Csernoch, L.; Pócsi, I. Urinary Biomarkers of Mycotoxin Induced Nephrotoxicity—Current Status and Expected Future Trends. Toxins 2021, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Biomarker Qualification Letter of Intent (LOI) Template. 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/135910/download (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Rached, E.; Hoffmann, D.; Blumbach, K.; Weber, K.; Dekant, W.; Mally, A. Evaluation of Putative Biomarkers of Nephrotoxicity after Exposure to Ochratoxin A In Vivo and In Vitro. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 103, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, M.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Attina, T.; Naidu, M.; Rajendiran, K.; Warady, B.; Furth, S.; Vento, S.; Trachtman, H.; et al. Serially Assessed Bisphenol A and Phthalate Exposure and Association with Kidney Function in Children with Chronic Kidney Disease in the US and Canada: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. PLoS Med 2020, 17, e1003384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de León-Martínez, L.D.; Díaz-Barriga, F.; Barbier, O.; Ortíz, D.L.G.; Ortega-Romero, M.; Pérez-Vázquez, F.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Evaluation of emerging biomarkers of renal damage and exposure to aflatoxin-B1 in Mexican indigenous women: A pilot study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 12205–12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mousawi, M.; Tlais, S.; Alkatib, A.; Hussein, H.S.H. Consumption and Effect of Artificial Sweeteners and Artificially Sweetened Products on Lebanese Population. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 5, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudrimont, I.; Sostaric, B.; Yenot, C.; Betbeder, A.M.; Dano, S.; Sanni, A.; Steyn, P.S.; Creppy, E. Aspar-tame Prevents the Karyomegaly Induced by Ochratoxin A in Rat Kidney. Arch. Toxicol. 2001, 75, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.; Hong, X.; Li, L.; Qin, X.; Fu, H.; Liu, Y. Chronic alcohol consumption aggravates acute kidney injury through integrin β1/JNK signaling. Redox Biol. 2024, 77, 103386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergent, T.; Garsou, S.; Schaut, A.; De Saeger, S.; Pussemier, L.; Van Peteghem, C.; Larondelle, Y.; Schneider, Y.-J. Differential modulation of Ochratoxin A absorption across Caco-2 cells by dietary hplnols, used at realistic intestinal concentrations. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 159, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.A.; Cai, Y. Nuts, especially walnuts, have both antioxidant quantity and efficacy and exhibit significant potential health benefits. Food Funct. 2011, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solfrizzo, M.; Gambacorta, L.; Visconti, A. Assessment of Multi-Mycotoxin Exposure in Southern Italy by Urinary Multi-Biomarker Determination. Toxins 2014, 6, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ayoubi, M.; Salman, M.; Gambacorta, L.; Darra, N.; Solfrizzo, M. Assessment of Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A in Lebanese Students and Its Urinary Biomarker Analysis. Toxins 2021, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.; Brereton, P.; MacDonald, S. Assessment of Dietary Exposure to Ochratoxin A in the UK Using a Duplicate Diet Approach and Analysis of Urine and Plasma Samples. Food Addit. Contam. 2002, 18, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, K.; Blaszkewicz, M.; Degen, G.H. Simultaneous analysis of Ochratoxin A and its major metabolite ochratoxin alpha in plasma and urine for an advanced biomonitoring of the mycotoxin. J. Chromatogr. B 2010, 878, 2623–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennekou, S.H.; Allende, A.; Bearth, A.; Casacuberta, J.; Castle, L.; Coja, T.; Crépet, A.; Halldorsson, T.; Hoogenboom, L.; Knutsen, H.; et al. Statement on the use and interpretation of the margin of exposure approach. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Toh, Q.; Teo, B. Normalisation of urinary biomarkers to creatinine for clinical practice and research—When and why. Singap. Med. J. 2015, 56, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall (n = 442) N (%) | Male (n = 196) N (%) | Female (n = 246) N (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age category | 10–13 years | 172 (38.9%) | 95 (48.5%) | 77 (31.3%) | <0.001 * |

| 14–18 years | 270 (61.1%) | 101 (51.5%) | 169 (68.7%) | ||

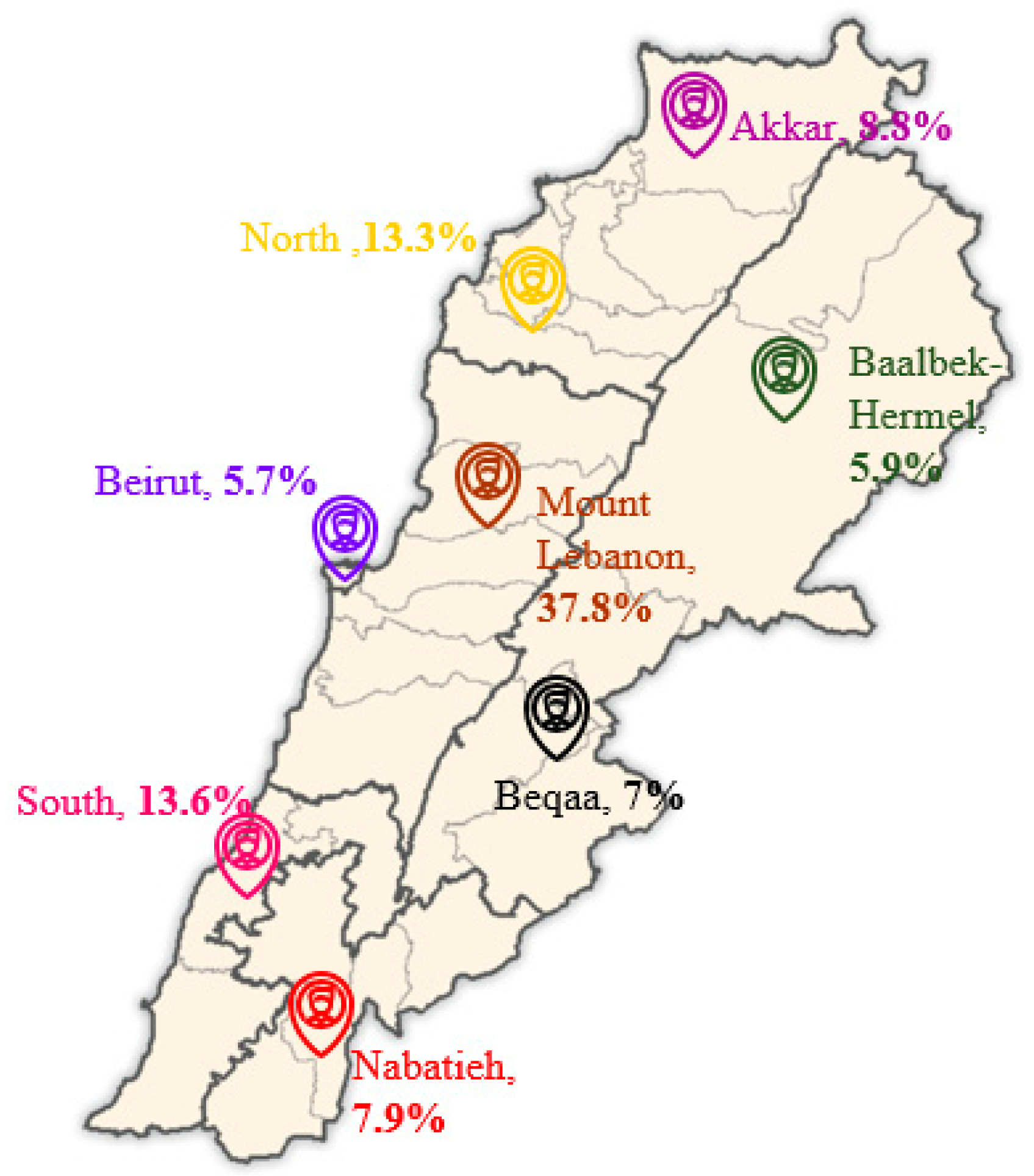

| Residence | Mount Lebanon | 167 (37.8%) | 85 (43.4%) | 82 (33.3%) | 0.588 |

| Beirut | 25 (5.7%) | 6 (3.1%) | 19 (7.7%) | ||

| South Lebanon | 60 (13.6%) | 20 (10.2%) | 40 (16.3%) | ||

| North Lebanon | 59 (13.3%) | 19 (9.7%) | 40 (16.3%) | ||

| Akkar | 39 (8.8%) | 15 (7.7%) | 24 (9.8%) | ||

| Nabatieh | 35 (7.9%) | 20 (10.2%) | 15 (6.1%) | ||

| Beqaa | 31 (7.0%) | 14 (7.1%) | 17 (6.9%) | ||

| Baalbek-Hermel | 26(5.9%) | 17 (8.7%) | 9 (3.7%) | ||

| Primary caregiver (n = 440) | Mother only | 15 (3.4%) | 7 (3.5%) | 8 (3.2%) | 0.255 |

| Father only | 8 (1.8%) | 4 (2.05%) | 4 (1.6%) | ||

| Both parents | 407 (92.5%) | 182 (93.3%) | 225 (91.8%) | ||

| Others | 10 (2.3%) | 2 (1.02%) | 8 (3.2%) | ||

| Education level | Elementary school level (grades 1–6) | 112 (25.3%) | 61 (31.1%) | 51 (20.7%) | <0.001 * |

| Intermediate school level (grades 7–9) | 119 (26.9%) | 67 (34.2%) | 52 (21.1%) | ||

| Secondary school level (grades 10–12)/vocational | 122 (27.6%) | 48 (24.5%) | 74 (30.1%) | ||

| University level | 89 (20.1%) | 20 (10.2%) | 69 (28%) | ||

| Illiterate | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Mother education level | Elementary school level (grades 1–6) | 72 (16.3%) | 30 (15.3%) | 42 (17.1%) | 0.707 |

| Intermediate school level (grades 7–9) | 106 (24%) | 45 (23%) | 61 (24.8%) | ||

| Secondary school level (grades 10–12)/vocational | 106 (24%) | 48 (24.5%) | 58 (23.6%) | ||

| University level | 140 (31.7%) | 64 (32.7%) | 76 (30.9%) | ||

| Illiterate | 18 (4.1%) | 9 (4.6%) | 9 (3.7%) | ||

| Father education level | Elementary school level (grades 1–6) | 101 (22.9%) | 45 (23%) | 56 (22.8%) | 0.822 |

| Intermediate school level (grades 7–9) | 104 (23.5%) | 40 (20.4%) | 64 (26%) | ||

| Secondary school level (grades 10–12)/vocational | 105 (23.8%) | 57 (29.1%) | 48 (19.5%) | ||

| University level | 113 (25.6%) | 46 (23.5%) | 67 (27.2%) | ||

| Illiterate | 19 (4.3%) | 8 (4.1%) | 11 (4.5%) | ||

| Working status (n = 441) | No | 413 (93.7%) | 180 (92.3%) | 233 (94.7%) | 0.314 |

| Yes | 28 (6.3%) | 15 (7.7%) | 13 (5.3%) |

| Variable | Overall (442) | Male (n = 196) | Female (n = 246) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Anthropometric values | ||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 53.66 | 16.08 | 54.61 | 18.83 | 52.91 | 13.49 | 0.289 | |

| Height (cm) | 157.57 | 12.37 | 159.44 | 14.83 | 156.09 | 9.76 | 0.007 * | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.24 | 4.52 | 20.95 | 4.87 | 21.47 | 4.22 | 0.234 | |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p-Value | ||

| BMI classification | Underweight | 20 | 4.5% | 15 | 7.7% | 5 | 2% | 0.072 |

| Healthy | 304 | 68.8% | 120 | 61.2% | 184 | 74.8% | ||

| Overweight | 64 | 14.5% | 25 | 12.8% | 39 | 15.9% | ||

| Obesity and severe obesity | 54 | 12.2% | 36 | 18.4% | 18 | 7.3% | ||

| Food Groups | Dietary Intake | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 446) | Female (n = 246) | Male (n = 196) | |||||

| Mean± | SD | Mean± | SD | Mean± | SD | p-Value | |

| Bread, cereals, and grains (g/d) | 333.98± | 163.25 | 296.01± | 139.34 | 381.62± | 178.27 | <0.001 * |

| Legumes (g/d) | 72.27± | 58.69 | 72.53± | 57.30 | 71.95± | 60.53 | 0.919 |

| Nuts and seeds (g/d) | 44.56± | 224.78 | 35.22± | 55.65 | 56.28± | 331.86 | 0.381 |

| Vegetables (g/d) | 236.64± | 148.77 | 249.24± | 157.26 | 220.82± | 136.14 | 0.046 * |

| Starchy vegetables (g/d) | 74.67± | 77.25 | 72.91± | 57.61 | 76.87± | 96.53 | 0.593 |

| Dairy products (g/d) | 205.28± | 177.28 | 183.83± | 179.82 | 232.19± | 170.71 | 0.004 * |

| Meat and Meat Products, Poultry, Fish, Eggs | |||||||

| Red meat (g/d) | 29.86± | 32.51 | 27.31± | 29.15 | 33.06± | 36.12 | 0.065 |

| Processed meat (g/d) | 6.93± | 14.17 | 6.20± | 11.11 | 7.85± | 17.25 | 0.225 |

| Poultry (g/d) | 34.52± | 35.43 | 33.18± | 30.91 | 36.20± | 40.41 | 0.375 |

| Fish (g/d) | 6.89± | 22.04 | 4.91± | 8.63 | 9.38± | 31.53 | 0.055 |

| Eggs (g/d) | 30.07± | 45.67 | 22.69± | 26.94 | 39.34± | 60.41 | <0.001 * |

| Fruits, Total | |||||||

| Fruits (g/d) | 253.62± | 192.07 | 260.62± | 202.76 | 244.83± | 177.86 | 0.391 |

| Fresh juices (100% fresh juices) (mL/d) | 50.77± | 74.86 | 53.58± | 81.04 | 47.23± | 66.34 | 0.376 |

| Sweets and Added Sugars | |||||||

| Sweets (g/d) | 94.51± | 70.76 | 89.35± | 69.68 | 100.97± | 71.76 | 0.086 |

| Added sugars, jams, honey, and molasses (g/d) | 21.45± | 22.42 | 18.43± | 14.96 | 25.23± | 28.81 | 0.003 * |

| Hot beverages (mL/d) | 163.15± | 168.96 | 167.41± | 169.85 | 157.80± | 168.11 | 0.553 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages (mL/d) | 142.37± | 173.67 | 129.62± | 172.64 | 158.36± | 174.07 | 0.084 |

| Alcoholic beverages (mL/d) | 2.56± | 23.60 | 2.08± | 24.04 | 3.15± | 23.09 | 0.637 |

| Added fats and oils (g/d) | 59.38± | 43.37 | 55.26± | 27.76 | 64.56± | 56.90 | 0.037 * |

| Food Groups | Dietary Intake | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–13 Years (n = 172) | 14–18 Years (n = 270) | p-Value | |||

| Mean± | SD | Mean± | SD | ||

| Bread, cereals, and, grains (g/d) | 337.06± | 154.95 | 332.01± | 168.58 | 0.752 |

| Legumes (g/d) | 70.44± | 57.57 | 73.44± | 59.47 | 0.602 |

| Nuts and seeds (g/d) | 30.38± | 58.62 | 53.59± | 283.62 | 0.290 |

| Vegetables (g/d) | 217.92± | 139.28 | 248.56± | 153.59 | 0.031 * |

| Starchy vegetables (g/d) | 70.31± | 78.21 | 77.44± | 76.65 | 0.345 |

| Dairy products(g/d) | 225.32± | 192.54 | 192.51± | 165.95 | 0.058 |

| Meat and Meat Products, Poultry, Fish, Eggs | |||||

| Red meat (g/d) | 26.65± | 26.93 | 31.91± | 35.51 | 0.098 |

| Processed meat (g/d) | 4.91± | 8.38 | 8.22± | 16.74 | 0.006 * |

| Poultry (g/d) | 31.33± | 38.34 | 36.55± | 33.36 | 0.131 |

| Fish (g/d) | 4.19± | 6.63 | 8.61± | 27.59 | 0.012 * |

| Eggs (g/d) | 31.30± | 54.71 | 29.29± | 38.92 | 0.653 |

| Fruits, Total | |||||

| Fruits (g/d) | 262.38± | 194.15 | 248.03± | 190.87 | 0.444 |

| Fresh juices (100% fresh juices) (mL/d) | 49.52± | 79.53 | 51.56± | 71.88 | 0.780 |

| Sweets and Added Sugars | |||||

| Sweets (g/d) | 93.11± | 65.77 | 95.40± | 73.88 | 0.740 |

| Added sugars, jams, honey, and molasses (g/d) | 17.91± | 14.95 | 23.70± | 25.87 | 0.003 * |

| Hot beverages (mL/d) | 129.80± | 123.37 | 184.39± | 189.63 | <0.001 * |

| Non-alcoholic beverages (mL/d) | 144.47± | 184.10 | 141.02± | 167.02 | 0.839 |

| Alcoholic beverages (mL/d) | .00± | .00 | 4.18± | 30.11 | 0.023 * |

| Added fats and oils (g/d) | 59.35± | 51.10 | 59.40± | 37.74 | 0.990 |

| Food Group | Dietary Intake (g/day) | Mean OTA (μg/kg) | EDI (ng/kg bw/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals and cereal-based products | 231.85 | 0.85 | 3.68 |

| Nuts and oilseeds | 11.26 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Legumes and pulses | 59.63 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Milk and dairy products | 110.85 | - | - |

| Fruits and fruit products | 16.38 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Herbs, spices, and condiments | 4.94 | 2.87 | 0.26 |

| Desserts and snacks | 56.21 | 0.33 | 0.35 |

| Stimulant beverages | 54.84 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages | 0.65 | - | - |

| Alcoholic beverages | 2.09 | 0.87 | 0.03 |

| Total | 4.92 |

| Mycotoxin Biomarker | ||

|---|---|---|

| OTα (μg/L) | OTA (μg/L) | |

| Positive samples | 238 (59.5%) | 57 (14.2%) |

| Mean | 3.54 | 1.01 |

| Kim-1 (pg/mL) | NGAL (pg/mL) | NAG (mU/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive samples n (%) | 344 (86%) | 400 (100%) | 400 (100%) |

| Mean | 325.7 | 57.4 | 175.3 |

| Ratio to urinary Cr | 0.38 ng/mg Cr | 0.08 ng/mg Cr | 1.71 mU/mg Cr |

| >Cut-off | 0 | 0 | 6 (1.5%) |

| Total Protein (mg/dL) | Creatinine (mg/dL) | TP/Creatinine | |

| Mean | 11.6 | 124.4 | 0.11 |

| >Cut-off | - | - | 21 (5.25%) |

| NGAL | Beans | 0.133 |

| Croissant | 0.131 | |

| Beer | 0.215 | |

| Wine | 0.144 | |

| Liquor/whiskey/vodka/gin/rum | 0.162 | |

| Kim-1 | Brown bread | 0.181 |

| Green peas | 0.159 | |

| Energy drinks | 0.139 | |

| Liquor/whiskey/vodka/gin/rum | 0.151 | |

| NAG | Regular breakfast cereal | 0.163 |

| Canola oil | 0.186 | |

| Beer | 0.169 | |

| Liquor/whiskey/vodka/gin/rum | 0.134 | |

| OTα | Peanuts | −0.150 |

| Almonds | −0.176 | |

| Walnuts | −0.180 | |

| Cake | −0.134 | |

| Chocolate bar | −0.138 | |

| Corn oil | 0.148 | |

| Canola oil | −0.158 | |

| Turkish coffee | 0.190 |

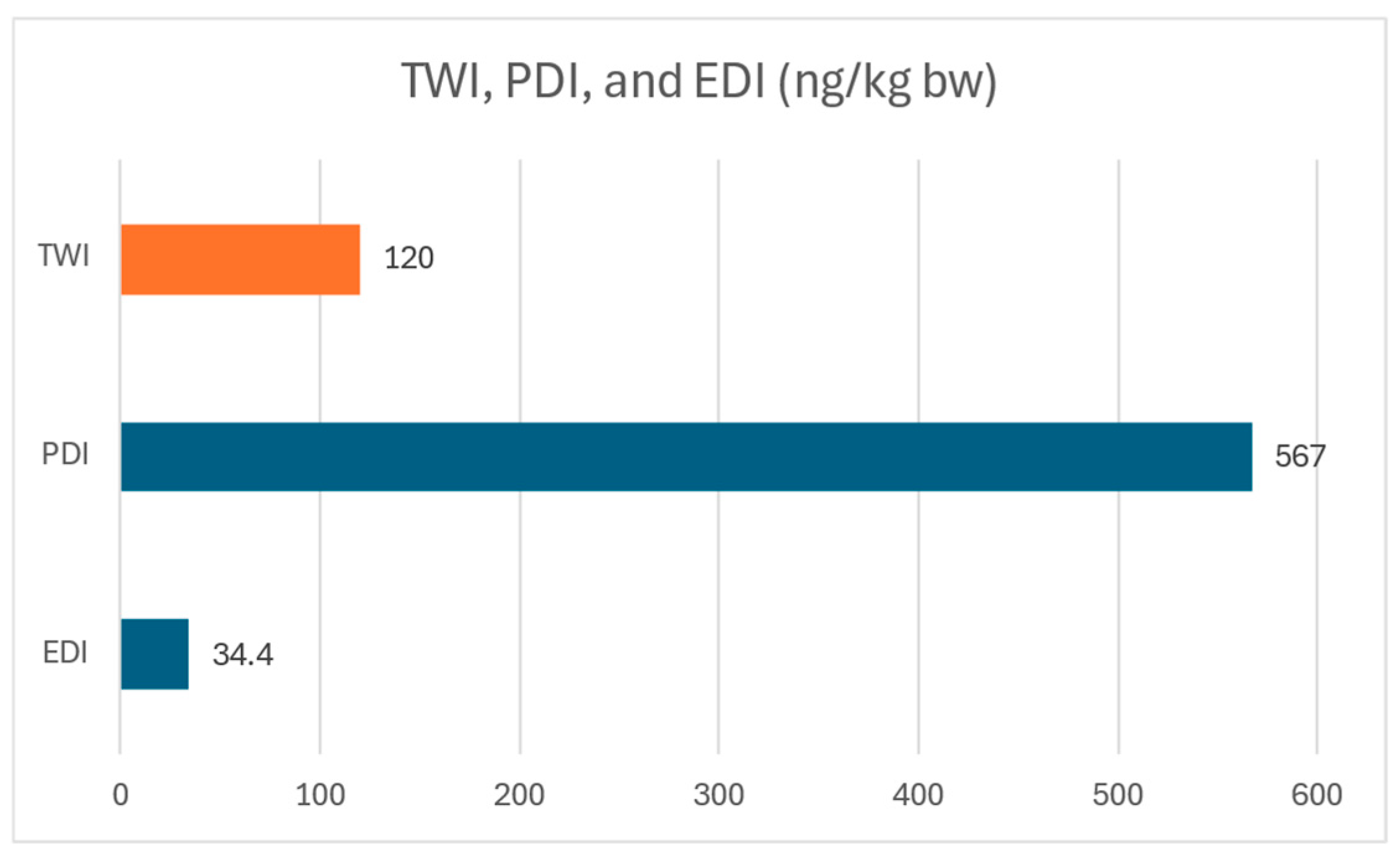

| Weekly Intake (ng/kg bw) | MOE Neoplastic | MOE Non-Neoplastic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDI (ng/kg bw/day) | 81 | 567 | 180 | 59 |

| EDI (ng/kg bw/day) | 4.92 | 34.44 | 2947 | 961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daou, R.; Hoteit, M.; Chémali, J.; Tzenios, N.; Fares, N.; El Khoury, A. Assessing Kidney Injury Biomarkers and OTA Exposure in Urine of Lebanese Adolescents Amid Economic Crisis and Evolving Dietary Patterns. Toxins 2025, 17, 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120577

Daou R, Hoteit M, Chémali J, Tzenios N, Fares N, El Khoury A. Assessing Kidney Injury Biomarkers and OTA Exposure in Urine of Lebanese Adolescents Amid Economic Crisis and Evolving Dietary Patterns. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120577

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaou, Rouaa, Maha Hoteit, Jad Chémali, Nikolaos Tzenios, Nassim Fares, and André El Khoury. 2025. "Assessing Kidney Injury Biomarkers and OTA Exposure in Urine of Lebanese Adolescents Amid Economic Crisis and Evolving Dietary Patterns" Toxins 17, no. 12: 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120577

APA StyleDaou, R., Hoteit, M., Chémali, J., Tzenios, N., Fares, N., & El Khoury, A. (2025). Assessing Kidney Injury Biomarkers and OTA Exposure in Urine of Lebanese Adolescents Amid Economic Crisis and Evolving Dietary Patterns. Toxins, 17(12), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120577