Toxins and the Kidneys: A Two-Way Street

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nephrotoxin-Mediated Acute Kidney Injury

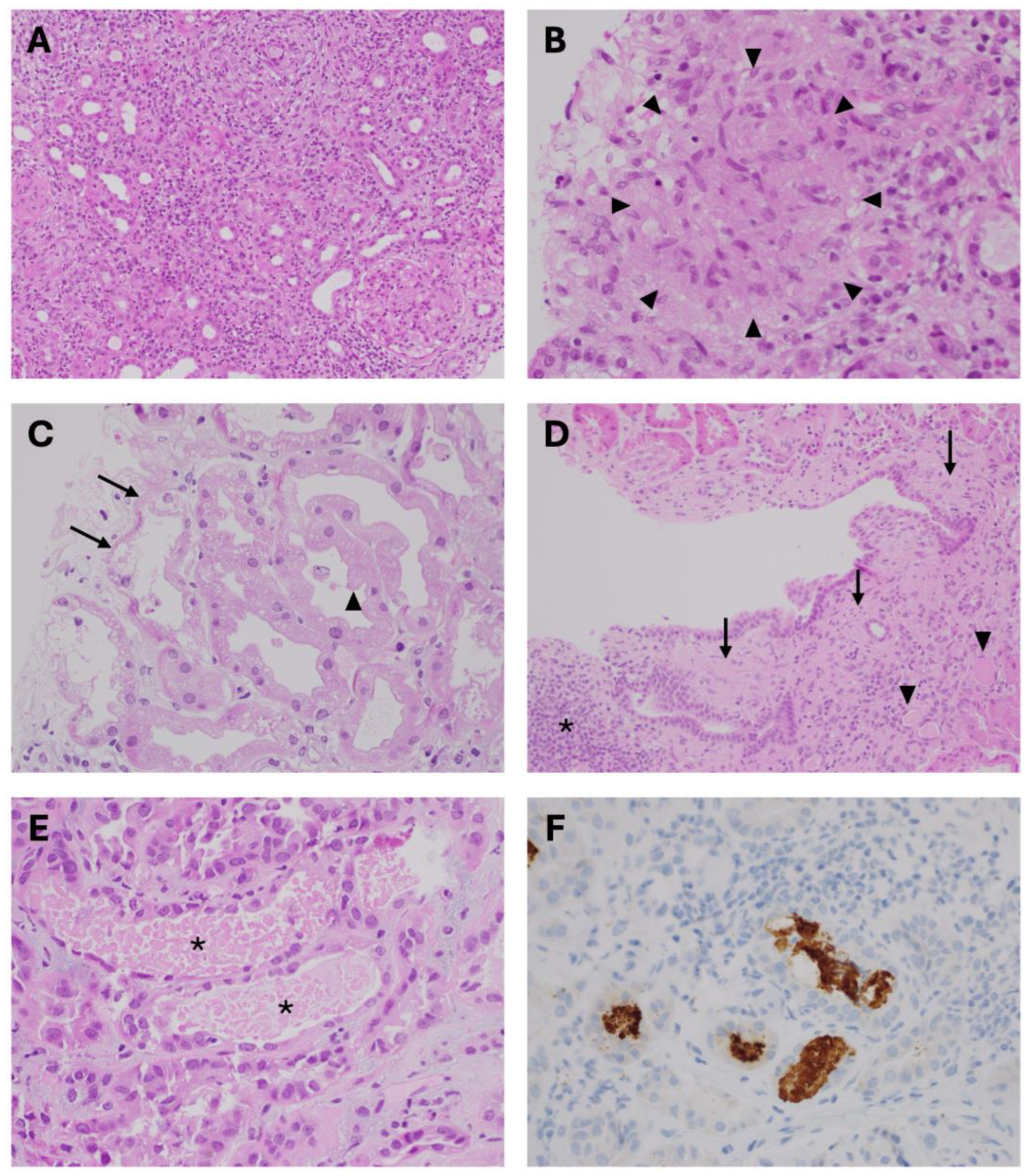

2.1. Exogenous Nephrotoxins Affecting Renal Tubulo-Interstitial Compartment

2.2. Endogenous Nephrotoxins Affecting Renal Tubular Cells

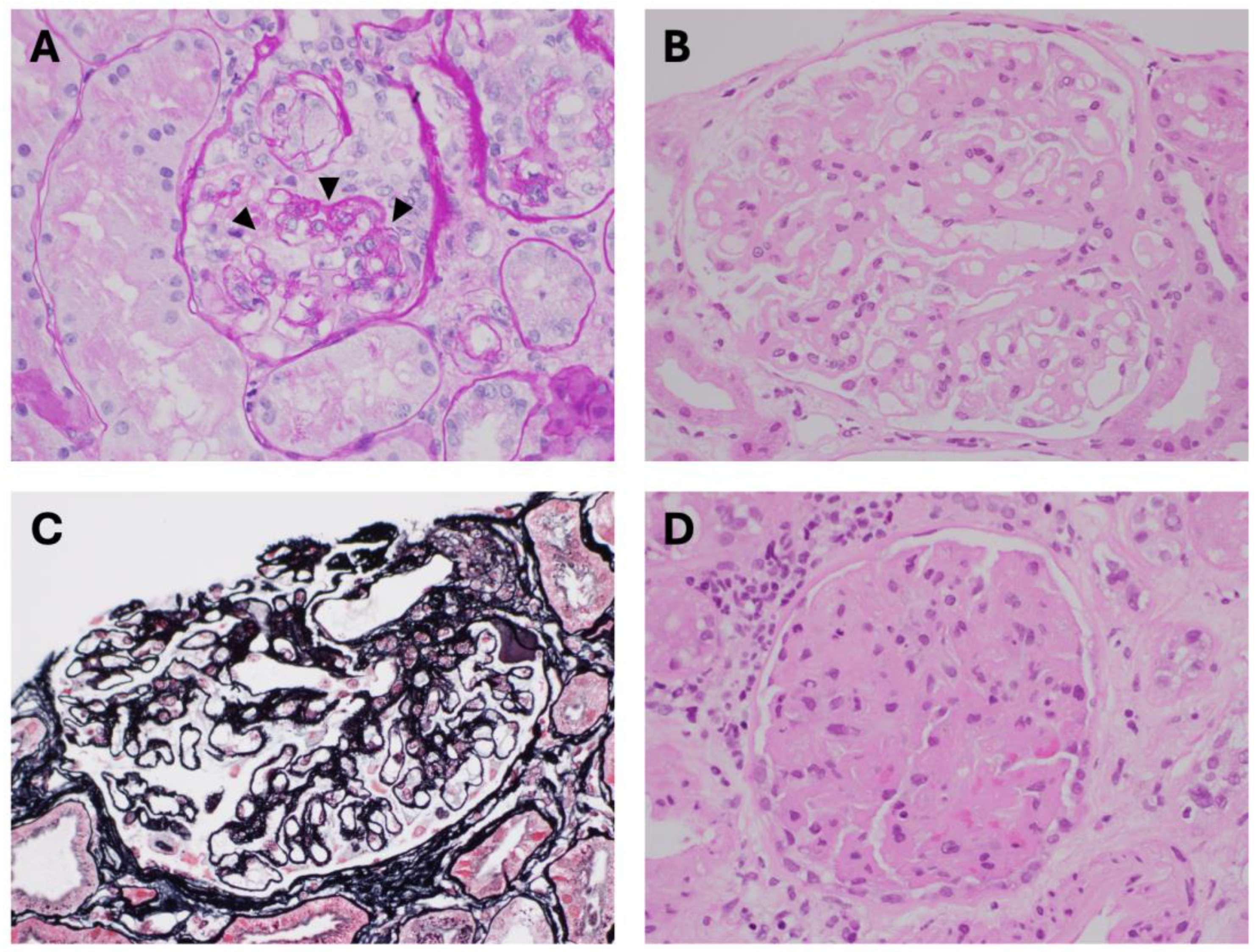

2.3. Nephrotoxins Affecting Glomeruli and Renal Microvasculature

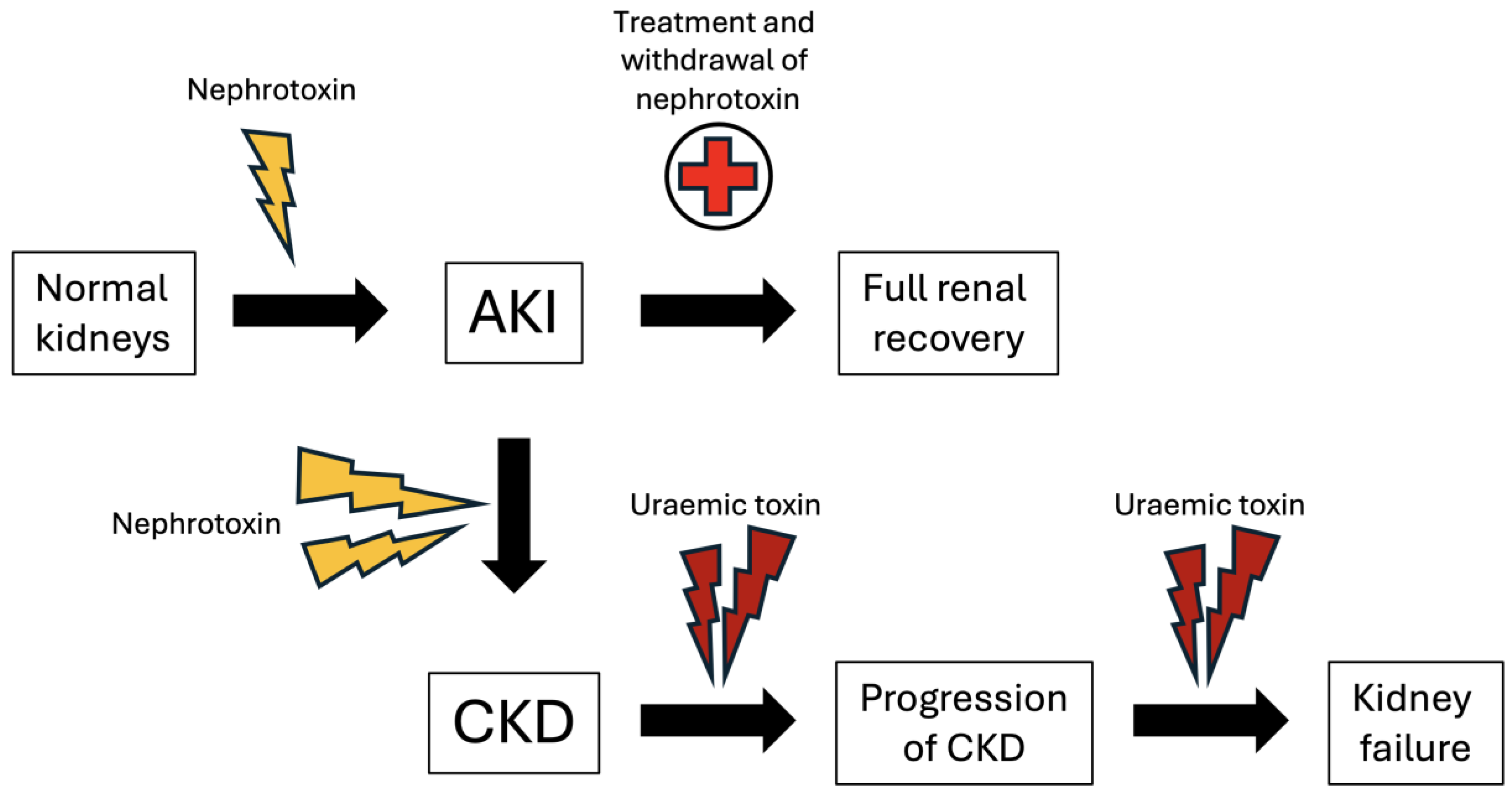

3. AKI to CKD Transition and Accumulation of Uraemic Toxins

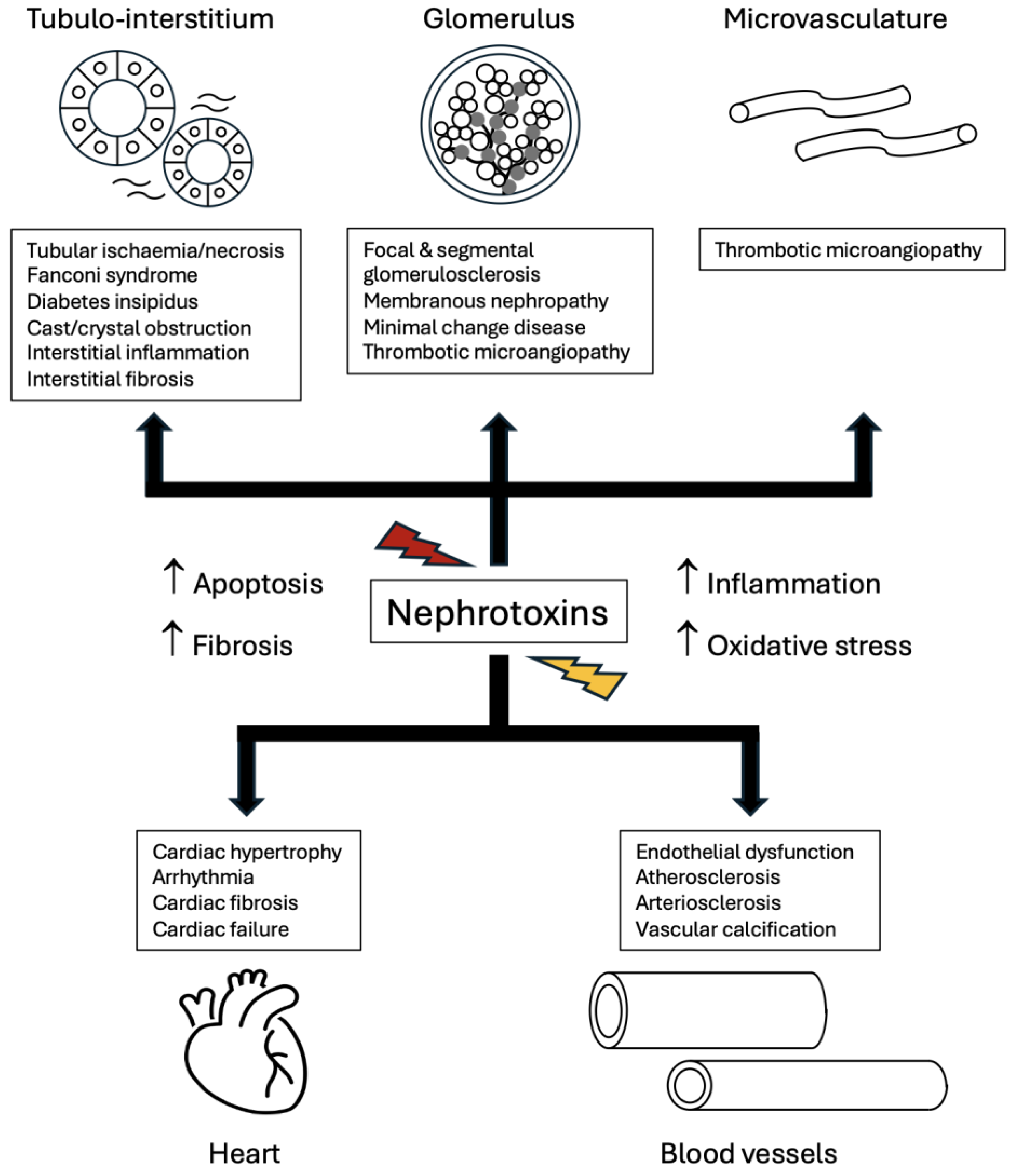

4. Uraemic Toxins Affecting Kidneys and Beyond

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostermann, M.; Lumlertgul, N.; Jeong, R.; See, E.; Joannidis, M.; James, M. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 2025, 405, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Koreeda, D.; Kobayashi, S.; Yano, T.; Tatsuta, K.; Mima, T.; Shigematsu, T.; Ohya, M. Acute kidney injury: Epidemiology, outcomes, complications, and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, D.; Sud, K. Acute kidney injury and disease: Long-term consequences and management. Nephrology 2018, 23, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.L.; Awdishu, L.; Davenport, A.; Murray, P.T.; Macedo, E.; Cerda, J.; Chakaravarthi, R.; Holden, A.L.; Goldstein, S.L. Phenotype standardization for drug-induced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.S.; Eggers, P.W.; Star, R.A.; Kimmel, P.L. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikizler, T.A.; Parikh, C.R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Liu, K.D.; Coca, S.G.; Garg, A.X.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Siew, E.D.; Wurfel, M.M.; et al. A prospective cohort study of acute kidney injury and kidney outcomes, cardiovascular events, and death. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmena, R.; Ascaso, J.F.; Redon, J. Chronic kidney disease as a cardiovascular risk factor. J. Hypertens 2020, 38, 2110–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D.S.; Levine, B.B.; McCluskey, R.T.; Gallo, G.R. Renal failure and interstitial nephritis due to penicillin and methicillin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1968, 279, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A.; Markowitz, G.S. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2010, 6, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakashita, K.; Murata, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Oohashi, K.; Sato, Y.; Kitazono, M.; Wada, A.; Takamori, M. A case series of acute kidney injury during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.R.; Trott, S.A.; Philbrick, J.T. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Am. J. Nephrol. 1992, 12, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, J.; Brown, C.; Chotirmall, S.; Dorman, A.; Conlon, P.; Walshe, J. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced acute interstitial nephritis in renal allografts; clinical course and outcome. Clin. Nephrol. 2009, 72, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, B.; Giebel, S.; McCarron, M.; Prasad, B. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor-induced acute interstitial nephritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomjit, N.; Ungprasert, P. Acute kidney injury associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 101, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, I.J.; Marshall, M.R.; Pilmore, H.; Manley, P.; Williams, L.; Thein, H.; Voss, D. Proton pump inhibitors and acute interstitial nephritis: Report and analysis of 15 cases. Nephrology 2006, 11, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Ghamrawi, R.; Chengappa, M.; Goksu, B.N.B.; Kottschade, L.; Finnes, H.; Dronca, R.; Leventakos, K.; Herrmann, J.; Herrmann, S.M. Acute interstitial nephritis and checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Single center experience of management and drug rechallenge. Kidney 2020, 360, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Jiang, L.; Su, T.; Liu, G.; Yang, L. Overview of aristolochic acid nephropathy: An update. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 42, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.; Shortland, J.R.; Maddocks, J.L. Interstitial nephritis associated with frusemide. J. R. Soc. Med. 1986, 79, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Carter-Monroe, N.; Atta, M.G. Granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Clin. Kidney J. 2015, 8, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Alamo, B.; Cases-Corona, C.; Fernandez-Juarez, G. Facing the challenge of drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nephron 2022, 147, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaut, M.; Schentag, J.; Jusko, W. Nephrotoxicity with gentamicin or tobramycin. Lancet 1979, 314, 526–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, X. Gentamicin aggravates renal injury by affecting mitochondrial dynamics, altering renal transporters expression, and exacerbating apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 412, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, A.; Kawanishi, K.; Morikawa, S.; Nakano, T.; Kodama, M.; Mitobe, M.; Taneda, S.; Koike, J.; Ohara, M.; Nagashima, Y.; et al. Biopsy-proven vancomycin-induced acute kidney injury: A case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlitz, L.C.; Mohan, S.; Stokes, M.B.; Radhakrishnan, J.; D’Agati, V.D.; Markowitz, G.S. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity: Acute tubular necrosis with distinctive clinical, pathological, and mitochondrial abnormalities. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leowattana, W. Antiviral drugs and acute kidney injury (AKI). Infect. Disord.—Drug Targets 2019, 19, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkok, A.; Edelstein, C.L. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 967826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, C.M.; Ueberroth, J.; Page, S.M.; Sehra, S.M. Acute tubular necrosis caused by zoledronic acid infusion in a patient with osteoporosis. Am. J. Ther. 2021, 29, e146–e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, R.; Dangas, G.D.; Weisbord, S.D. Contrast-associated acute kidney injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2146–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, F. Advances in the pathogenesis and prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoul, M.; Drüeke, T.B. Β2 Microglobulin Amyloidosis: An update 30 years later. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 31, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esson, M.L.; Schrier, R.W. Diagnosis and treatment of acute tubular necrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rajput, M.; Kumar, R.; Prasad, P.; Verma, H.; Mahajan, S.; Suri, J.; Batra, V. Postpartum renal cortical necrosis: Experience from a tertiary care center in India. J. Nephrol. 2025, 38, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockenhauer, D.; Bichet, D.G. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Slatter, T.; Walker, R. Lithium-induced kidney injury and fibrosis: A versatile model to explore cellular pathways of injury and repair. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurell, M.; Svalander, C.; Wallin, L.; Alling, C. Renal function and biopsy findings in patients on long-term lithium treatment. Kidney Int. 1981, 20, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.J.; Leader, J.P.; Bedford, J.J.; Gobe, G.; Davis, G.; Vos, F.E.; Dejong, S.; Schollum, J.B.W. Chronic interstitial fibrosis in the rat kidney induced by long-term (6-mo) exposure to lithium. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2013, 304, F300–F307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.M.; Gimenez, G.; Walker, R.J.; Slatter, T.L. Reduction of lithium induced interstitial fibrosis on co-administration with amiloride. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondo, L.; Abramowicz, M.; Alda, M.; Bauer, M.; Bocchetta, A.; Bolzani, L.; Calkin, C.V.; Chillotti, C.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Manchia, M.; et al. Long-term lithium treatment in bipolar disorder: Effects on glomerular filtration rate and other metabolic parameters. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, J.F.; Burfeind, K.G.; Malinoski, D.; Hutchens, M.P. Molecular mechanisms of rhabdomyolysis-induced kidney injury: From bench to bedside. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.C.; Zhang, S.; Pelger, C.B.; Lughmani, H.Y.; Haller, S.T.; Gunning, W.T.; Cooper, C.J.; Gong, R.; et al. Hemopexin accumulates in kidneys and worsens acute kidney injury by causing hemoglobin deposition and exacerbation of iron toxicity in proximal tubules. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Slambrouck, C.M.; Salem, F.; Meehan, S.M.; Chang, A. Bile cast nephropathy is a common pathologic finding for kidney injury associated with severe liver dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.R.P.; Williams, D.; Niewiadomski, O.D. Phosphate nephropathy: An avoidable complication of bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholder, R.; Sever, M.S.; Erek, E.; Lameire, N. Rhabdomyolysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000, 11, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mong, R.; Thng, S.Y.; Lee, S.W. Rhabdomyolysis following an intensive indoor cycling exercise: A series of 5 cases. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2021, 50, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, J.M.; Reed, G.; Knochel, J.P. Cocaine-associated rhabdomyolysis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1989, 297, 334–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montastruc, J. Rhabdomyolysis and statins: A pharmacovigilance comparative study between statins. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 2636–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, X.; Poch, E.; Grau, J.M. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.; Estienne, L.; Serpieri, N.; Ronchi, D.; Comi, G.P.; Moggio, M.; Peverelli, L.; Bianzina, S.; Rampino, T. Rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney Injury. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, A12–A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajema, I.M.; I Rotmans, J. Histological manifestations of rhabdomyolysis in the kidney. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, 2113–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knochel, J.P. Serum calcium derangements in rhabdomyolysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1981, 305, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N, M.H.; Pinto, C.J.; Poornima, J.; Rajput, A.K.; Bagheri, M.; Patil, B.; Nizamuddin, M. Classical paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria presenting with severe anemia and pigmented acute kidney injury. Cureus 2022, 14, e28448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattamis, A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Aydinok, Y. Thalassaemia. Lancet 2022, 399, 2310–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazinga, C.; Bednarski, O.; Aujo, J.C.; Lima-Cooper, G.; Oriba, D.L.; Plewes, K.; Conroy, A.L.; Namazzi, R. Acute kidney injury in severe malaria: A serious complication driven by hemolysis. Semin. Nephrol. 2025, 45, 151614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, W.C. Cephalosporin-induced hemolysis: A case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Hematol. 1992, 40, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, O.; Hoffmann, T.; Aslan, T.; Ahrens, N.; Kiesewetter, H.; Salama, A. Diclofenac-induced antibodies against RBCs and platelets: Two case reports and a concise review. Transfusion 2003, 43, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaçais, M.; Laparra, A.; Maria, A.T.J.; Kramkimel, N.; Perret, A.; Manson, G.; Comont, T.; Coutte, L.; Nardin, C.; Ouali, K.; et al. Drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemias related to immune checkpoint inhibitors, therapeutic management, and outcome. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, C.A.; Fan, B.E.; Lim, K.G.E.; Kuperan, P. Chronic dapsone use causing methemoglobinemia with oxidative hemolysis and dyserythropoiesis. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1715–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Fiorelli, G. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Lancet 2008, 371, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durani, U.; Hogan, W.J. Emergencies in haematology: Tumour lysis syndrome. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 188, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribrag, V.; Bron, D.; Rymkiewicz, G.; Hoelzer, D.; Jørgensen, J.; de Armas-Castellano, A.; Trujillo-Martín, M.; Fenaux, P.; Malcovati, L.; Bolaños, N.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in adults: Clinical practice guidelines from ERN-EuroBloodNet. Lancet Haematol. 2025, 12, e138–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.C.; Jones, D.P.; Pui, C.H. The Tumor lysis syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Kapanadze, T.; Weingärtner, N.; Walter, S.; Vogt, I.; Grund, A.; Schmitz, J.; Bräsen, J.H.; Limbourg, F.P.; Haffner, D.; et al. High phosphate-induced progressive proximal tubular injury is associated with the activation of Stat3/Kim-1 signaling pathway and macrophage recruitment. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullaro, G.; Kanduri, S.R.; Velez, J.C. Acute kidney injury in patients with liver disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniort, J.; Poyet, A.; Kemeny, J.-L.; Philipponnet, C.; Heng, A.-E. Bile cast nephropathy caused by obstructive cholestasis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 69, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, M.A.G.J.T.; Hilbrands, L.B.; Wetzels, J.F.M. Nephrotic syndrome induced by pamidronate. Med. Oncol. 2011, 28, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmer, M.; Amico, P.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Haschke, M.; Kummer, O.; Krähenbühl, S.; Mayr, M. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associated with long-term treatment with zoledronate in a myeloma patient. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 2366–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, Y.; Heibel, F.; Marcellin, L.; Chantrel, F.; Moulin, B.; Hannedouche, T. Acute renal failure and nephrotic syndrome with alpha interferon therapy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1997, 12, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jaffe, J.A.; Kimmel, P.L. Chronic nephropathies of cocaine and heroin abuse: A critical review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barri, Y.M.; Munshi, N.C.; Sukumalchantra, S.; Abulezz, S.R.; Bonsib, S.M.; Wallach, J.; Walker, P.D. Podocyte injury associated glomerulopathies induced by pamidronate. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, G.S.; Appel, G.B.; Fine, P.L.; Fenves, A.Z.; Loon, N.R.; Jagannath, S.; Kuhn, J.A.; Dratch, A.D.; D’Agati, V.D. Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis following treatment with high-dose pamidronate. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001, 12, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A.; Markowitz, G.S. Bisphosphonate nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roij van Zuijdewijn, C.; van Dorp, W.; Florquin, S.; Roelofs, J.; Verburgh, K. Bisphosphonate nephropathy: A case series and review of the literature. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 3485–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, D.S.; Kidd, E.G.; Shnitka, T.K.; Ulan, R.A. Gold nephropathy a clinical and pathologic study. Arthritis Rheum. 1970, 13, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.A.; Larsen, C.P.; Troxell, M.L. Membranous nephropathy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory Agents. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirim, A.B.; Hurdogan, O.; Oto, O.A.; Artan, A.S.; Suleymanova, V.; Demir, K.; Ormeci, A.C.; Ozluk, Y.; Ozturk, S.; Kilicaslan, I.; et al. NELL-1–associated membranous nephropathy induced by long-term penicillamine treatment in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 614–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, H.P.; Zeng, C.H.; Zheng, C.X.; Li, L.S.; Liu, Z.H. Mercury-induced membranous nephropathy: Clinical and pathological features. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, L.H.J.; Bonegio, R.G.; Lambeau, G.; Beck, D.M.; Powell, D.W.; Cummins, T.D.; Klein, J.B.; Salant, D.J. M-type phospholipase A2receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasare, R.S.; Andeen, N.K.; Al-Rabadi, L.F.; Burfeind, K.G.; Beck, L.H., Jr. Drug-induced membranous nephropathy: Piecing together clues to understand disease mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 36, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, J.; Perazella, M.A. Drug-induced glomerular disease: Attention required! Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, R.J. Secondary minimal change disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003, 18 (Suppl. 6), vi52–vi58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, A.V.; Masco, H.L.; Rifkin, S.I.; Acharya, M.K. Minimal-change disease and the nephrotic syndrome associated with lithium therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980, 92, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, D.S.; Patriquin, C.J.; Licht, C.; John, R.; Reich, H.N. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy: A review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 81, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.E.; Little, D.J.; Vesely, S.K.; George, J.N. Quinine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: A report of 19 patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; An, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, H. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with calcineurin inhibitors: A real-world analysis of postmarketing surveillance Data. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horino, T.; Ichii, O.; Shimamura, Y.; Terada, Y. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy caused by bevacizumab. Nephrology 2018, 23, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Pullman, J.M.; Coco, M. Cocaine and kidney injury: A kaleidoscope of pathology. Clin. Kidney J. 2014, 7, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Brassington, R.; Solez, K.; Bello, A. Chronic thrombotic microangiopathy presenting as acute nephrotic syndrome in a patient with renal cancer receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2024, 17, e255841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.S.; Kimmel, P.L. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: An integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int. 2012, 82, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perše, M.; Večerić-Haler, Ž. Cisplatin-induced rodent model of kidney injury: Characteristics and challenges. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1462802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L. Folic acid-induced animal model of kidney disease. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2021, 4, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Tang, C.; Cai, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, D.; Dong, Z. Rodent models of AKI-CKD transition. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2018, 315, F1098–F1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Widdop, R.E.; Ricardo, S.D. Transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: Mechanisms, models, and biomarkers. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2024, 327, F788–F805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Tan, R.J.; Liu, Y. Myofibroblast in kidney fibrosis: Origin, activation, and regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1165, 253–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shen, B.; Liu, X.; Fan, Y.; Qiu, J. Macrophages regulate renal fibrosis through modulating TGFβ superfamily signaling. Inflammation 2014, 37, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-y.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Coca, S.; Devarajan, P.; Ghahramani, N.; Go, A.S.; Hsu, R.K.; Ikizler, T.A.; Kaufman, J.; Liu, K.D.; et al. Post–acute kidney injury proteinuria and subsequent kidney disease progression: The assessment, serial evaluation, and subsequent sequelae in acute kidney injury (Assess-Aki) Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampe, B.; Zeisberg, M. Contribution of genetics and epigenetics to progression of kidney fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 29 (Suppl. 4), iv72–iv79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, W.; McGoohan, S.; Zeisberg, E.M.; Müller, G.A.; Kalbacher, H.; Salant, D.J.; Müller, C.A.; Kalluri, R.; Zeisberg, M. Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; De Smet, R.; Glorieux, G.; Argilés, A.; Baurmeister, U.; Brunet, P.; Clark, W.; Cohen, G.; De Deyn, P.P.; Deppisch, R.; et al. Review on uremic toxins: Classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Segre, J.A. Adapting Koch’s postulates. Science 2016, 351, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, A.; Vanholder, R.; Van Biesen, W.; Lameire, N. The removal of uremic toxins. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, S47–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.M.; Gullans, S.R.; Chin, W.W. Urea inducibility of Egr-1 in murine inner medullary collecting duct cells is mediated by the serum response element and adjacent ets motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 12903–12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.-Y.; Cohen, D.M. Urea-associated oxidative stress and Gadd153/CHOP induction. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1999, 276, F786–F793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Apolito, M.; Du, X.; Zong, H.; Catucci, A.; Maiuri, L.; Trivisano, T.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Campanozzi, A.; Raia, V.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Urea-induced ros generation causes insulin resistance in mice with chronic renal failure. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.J.; Hagge, W.W.; Wagoner, R.D.; Dinapoli, R.P.; Rosevear, J.W. Effects of urea loading in patients with far-advanced renal failure. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1972, 47, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, R.; Amato, D.; Vonesh, E.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Ramos, A.; Moran, J.; Mujais, S. Mexican nephrology collaborative study group effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, R.; Amato, D.; Vonesh, E.; Guo, A.; Mujais, S. Health-related quality of life predicts outcomes but is not affected by peritoneal clearance: The ADEMEX trial. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudville, N.; de Moraes, T.P. 2005 Guidelines on targets for solute and fluid removal in adults being treated with chronic peritoneal dialysis: 2019 update of the literature and revision of recommendations. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, F.; Ho, L.T. Dialysis-related amyloidosis: History and clinical manifestations. Semin. Dial. 2001, 14, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaweera, A.; Huang, L.; McMahon, L. Benefits and pitfalls of uraemic toxin measurement in peritoneal dialysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, T.; Ise, M. Indoxyl sulfate, a circulating uremic toxin, stimulates the progression of glomerular sclerosis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1994, 124, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Ise, M.; Hirata, M.; Endo, K.; Ito, Y.; Seo, H.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulfate stimulates renal synthesis of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and progression of renal failure. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1997, 63, S211–S214. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, H.; Bolati, D.; Adijiang, A.; Muteliefu, G.; Enomoto, A.; Nishijima, F.; Dateki, M.; Niwa, T. NF-κB plays an important role in indoxyl sulfate-induced cellular senescence, fibrotic gene expression, and inhibition of proliferation in proximal tubular cells. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2011, 301, C1201–C1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Yisireyili, M.; Nishijima, F.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulfate enhances p53-TGF-β1-Smad3 pathway in proximal tubular cells. Am. J. Nephrol. 2013, 37, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Honda, D.; Tanaka, H.; Wu, Q.; Endo, M.; Noguchi, T.; Kadowaki, D.; Ishima, Y.; Kotani, S.; et al. p-Cresyl sulfate causes renal tubular cell damage by inducing oxidative stress by activation of NADPH oxidase. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Yu, M.-A.; Ryu, E.S.; Jang, Y.-H.; Kang, D.-H. Indoxyl sulfate-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis of renal tubular cells as novel mechanisms of progression of renal disease. Lab. Investig. 2012, 92, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Chang, S.-C.; Wu, M.-S. Uremic toxins induce kidney fibrosis by activating intrarenal renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.-W.; Hsu, K.-H.; Lee, C.C.; Sun, C.-Y.; Hsu, H.-J.; Tsai, C.-J.; Tzen, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, M.-S. p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-J.; Pan, C.-F.; Chuang, C.-K.; Sun, F.-J.; Wang, D.-J.; Chen, H.-H.; Liu, H.-L.; Wu, C.-J. P-cresyl sulfate is a valuable predictor of clinical outcomes in pre-ESRD patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 526932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammens, B.; Evenepoel, P.; Keuleers, H.; Verbeke, K.; Vanrenterghem, Y. Free serum concentrations of the protein-bound retention solute p-cresol predict mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, B.K.; Claes, K.; Bammens, B.; de Loor, H.; Viaene, L.; Verbeke, K.; Kuypers, D.R.; Vanrenterghem, Y.; Evenepoel, P. p-Cresol and cardiovascular risk in mild-to-moderate kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Yoshida, M. Protein-bound uremic toxins: New culprits of cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease patients. Toxins 2014, 6, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Pathogenesis and mechanism of uremic vascular calcification. Cureus 2024, 16, e64771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumur, Z.; Shimizu, H.; Enomoto, A.; Miyazaki, H.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulfate upregulates expression of ICAM-1 and MCP-1 by oxidative stress-induced NF-ĸB activation. Am. J. Nephrol. 2010, 31, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J.R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Su, X.; Ni, J.; Du, R.; Zhang, R.; Jin, W. p-Cresyl sulfate promotes the formation of atherosclerotic lesions and induces plaque instability by targeting vascular smooth muscle cells. Front. Med. 2016, 10, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Hirose, Y.; Nishijima, F.; Tsubakihara, Y.; Miyazaki, H. ROS and PDFG-β receptors are critically involved in indoxyl sulfate actions that promote vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, C389–C396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Bertrand, E.; Cerini, C.; Faure, V.; Sampol, J.; Vanholder, R.; Berland, Y.; Brunet, P. The uremic solutes p-cresol and indoxyl sulfate inhibit endothelial proliferation and wound repair. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adijiang, A.; Goto, S.; Uramoto, S.; Nishijima, F.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulphate promotes aortic calcification with expression of osteoblast-specific proteins in hypertensive rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muteliefu, G.; Enomoto, A.; Jiang, P.; Takahashi, M.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulphate induces oxidative stress and the expression of osteoblast-specific proteins in vascular smooth muscle cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekawanvijit, S.; Adrahtas, A.; Kelly, D.J.; Kompa, A.R.; Wang, B.H.; Krum, H. Does indoxyl sulfate, a uraemic toxin, have direct effects on cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes? Eur. Hear. J. 2010, 31, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammens, B.; Evenepoel, P.; Verbeke, K.; Vanrenterghem, Y. Removal of middle molecules and protein-bound solutes by peritoneal dialysis and relation with uremic symptoms. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesaffer, G.; De Smet, R.; Lameire, N.; Dhondt, A.; Duym, P.; Vanholder, R. Intradialytic removal of protein-bound uraemic toxins: Role of solute characteristics and of dialyser membrane. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2000, 15, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, T.; Nomura, T.; Sugiyama, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Tsukushi, S.; Tsutsui, S. The protein metabolite hypothesis, a model for the progression of renal failure: An oral adsorbent lowers indoxyl sulfate levels in undialyzed uremic patients. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1997, 62, S23–S28. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, R.-H.; Kang, S.W.; Park, C.W.; Cha, D.R.; Na, K.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Yoon, S.A.; Han, S.Y.; Chang, J.H.; Park, S.K.; et al. A Randomized, controlled trial of oral intestinal sorbent AST-120 on renal function deterioration in patients with advanced renal dysfunction. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ospina, D.; Cote, M.R.; Bellido, L.C.; Calero, M.I.S.; Prieto, B.H.; Cuesta, S.D.; Herrera-Gómez, F.; Mujika-Marticorena, M.; Gonzalez-Parra, E.; Ortiz, M.J.I.; et al. Loop diuretics in anuric hemodialysis patients for the clearance of protein-bound uremic toxins. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfaf195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronov, P.A.; Luo, F.J.-G.; Plummer, N.S.; Quan, Z.; Holmes, S.; Hostetter, T.H.; Meyer, T.W. Colonic contribution to uremic solutes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirich, T.L.; Plummer, N.S.; Gardner, C.D.; Hostetter, T.H.; Meyer, T.W. Effect of increasing dietary fiber on plasma levels of colon-derived solutes in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xiong, Q.; Zhao, J.; Lin, X.; He, S.; Wu, N.; Yao, Y.; Liang, W.; Zuo, X.; Ying, C. Inulin-type fructan intervention restricts the increase in gut microbiome–generated indole in patients with peritoneal dialysis: A randomized crossover study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 1087–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tubulo-Interstitial Disease | Nephrotoxin |

|---|---|

| Acute interstitial nephritis | Antibiotics, e.g., penicillin, cephalosporins, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Proton pump inhibitors, e.g., omeprazole | |

| Lithium | |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors, e.g., pembrolizumab | |

| Aristolochia species | |

| Furosemide | |

| Acute tubular injury/necrosis | Exogenous |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Antibiotics, e.g., gentamicin, vancomycin | |

| Antivirals, e.g., acyclovir, tenofovir | |

| Antifungals, e.g., amphotericin B | |

| Cisplatin and carboplatin | |

| Zoledronic acid Iodinated contrast | |

| Fleet sodium phosphate | |

| Snake venom | |

| Endogenous | |

| Myoglobin | |

| Haemoglobin Bile salts | |

| Uric acid | |

| Phosphate | |

| Light chains |

| Glomerular Disease | Nephrotoxin |

|---|---|

| Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis | Zoledronic acid |

| Interferon | |

| Heroin | |

| Pamidronate | |

| Doxorubicin | |

| Calcineurin inhibitors, e.g., cyclosporin | |

| Anabolic steroids | |

| Membranous nephropathy | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Penicillamine | |

| Tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor | |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors, e.g., pembrolizumab | |

| Mercury | |

| Minimal change disease | Pamidronate Antibiotics, e.g., penicillin, cephalosporin, rifampicin Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs Lithium |

| Microvascular Disease | Nephrotoxin |

|---|---|

| Thrombotic microangiopathy | Quinine |

| Calcineurin inhibitors, e.g., cyclosporin | |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor, e.g., bevacizumab | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | |

| Gemcitabine | |

| Clopidogrel | |

| Cocaine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.L.; Longano, A.; McMahon, L.P. Toxins and the Kidneys: A Two-Way Street. Toxins 2025, 17, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120578

Huang LL, Longano A, McMahon LP. Toxins and the Kidneys: A Two-Way Street. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):578. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120578

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Louis L., Anthony Longano, and Lawrence P. McMahon. 2025. "Toxins and the Kidneys: A Two-Way Street" Toxins 17, no. 12: 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120578

APA StyleHuang, L. L., Longano, A., & McMahon, L. P. (2025). Toxins and the Kidneys: A Two-Way Street. Toxins, 17(12), 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120578