Bioenhancer Assessment of Black Pepper with Turmeric on Self-Reported Pain Ratings in Adults: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statement of Ethics and Approval

2.2. Participants

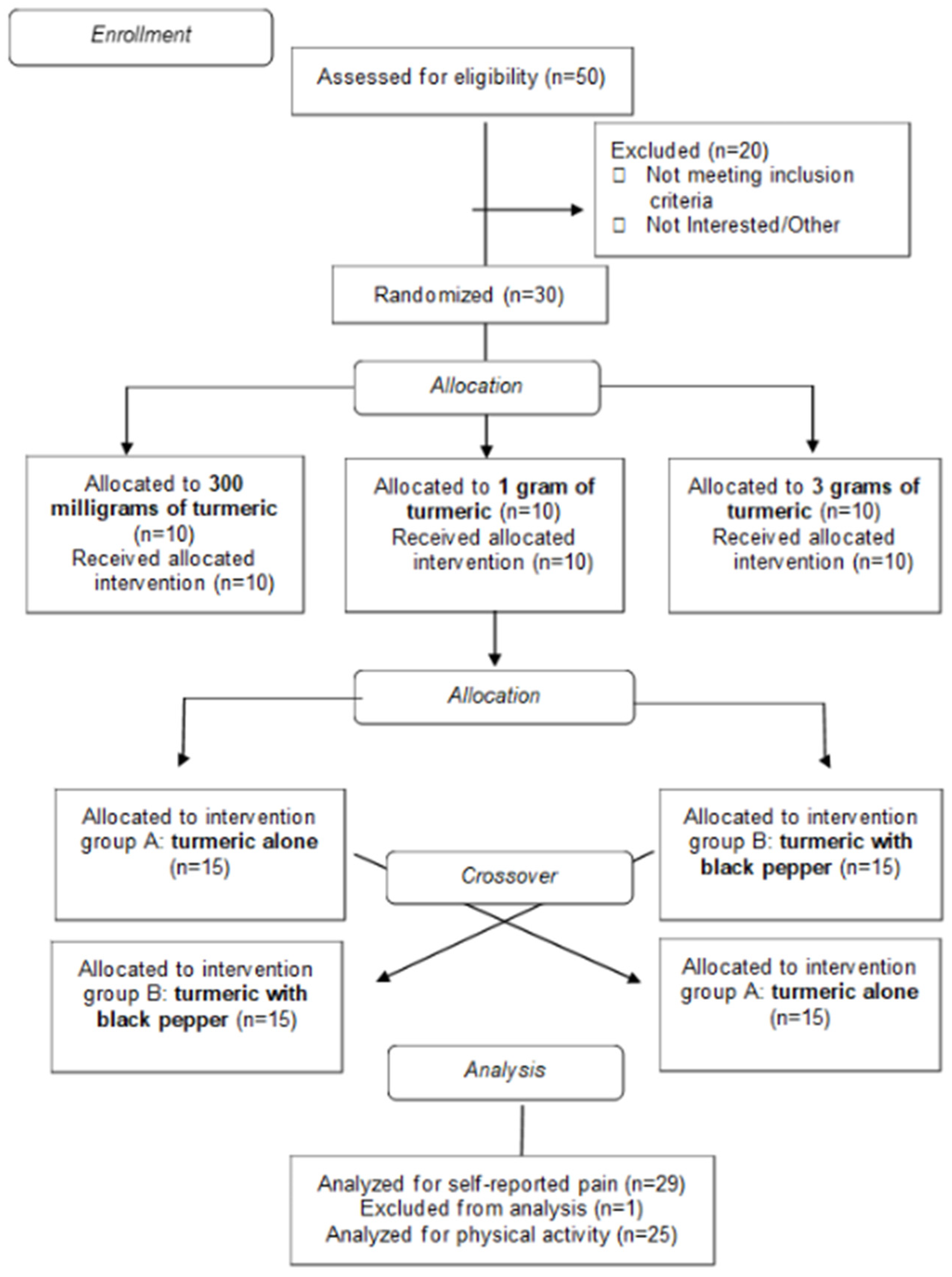

2.3. Experimental Design and Study Overview

2.4. Nutrition Intervention

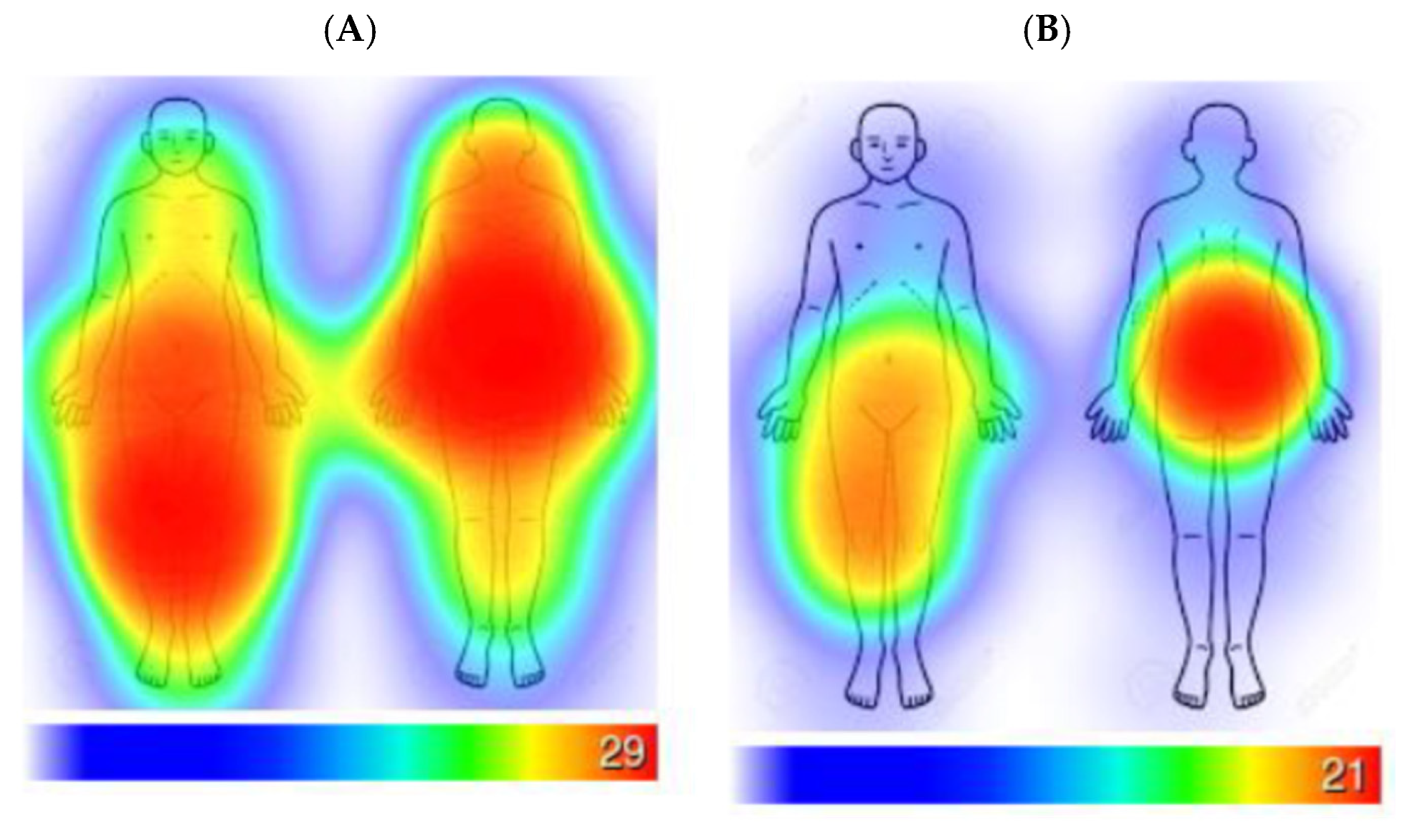

Self-Reported Pain Ratings

2.5. Physical Activity Monitoring

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Turmeric Alone Versus Turmeric with Black Pepper

3.2. Physical Activity

3.3. Turmeric Amount Comparisons

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Black Pepper |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- Mills, S.E.E.; Nicolson, K.P.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain: A review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e273–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikard, S.M.; Strahan, A.E.; Schmit, K.M.; Guy, G.P., Jr. Chronic Pain Among Adults—United States, 2019-2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonezzi, C.; Fornasari, D.; Cricelli, C.; Magni, A.; Ventriglia, G. Not All Pain is Created Equal: Basic Definitions and Diagnostic Work-Up. Pain Ther. 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, W.C.; Dorflinger, L.; Edmond, S.N.; Islam, L.; Heapy, A.A.; Fraenkel, L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Fam. Pract. 2017, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.L.; Grandpre, J.; Katz, D.L.; Shenson, D. The impact of key modifiable risk factors on leading chronic conditions. Prev. Med. 2019, 120, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A.; Parascandolo, I. Role of Nutrition in the Management of Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 2223–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.; Demmers, T.A.; Plourde, H.; Arrey, K.; Armour, B.; Ferland, G.; Kakinami, L. Identifying Barriers of Arthritis-Related Disability on Food Behaviors to Guide Nutrition Interventions. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanittum, P.; Kunyanone, N.; Brown, J.; Sangkomkamhang, U.S.; Barnes, J.; Seyfoddin, V.; Marjoribanks, J. Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD002124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, P.; Cerdá, B.; Arcusa, R.; Marhuenda, J.; Yamedjeu, K.; Zafrilla, P. Effect of Ginger on Inflammatory Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its’ Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishehbor, F.; Rezaeyan Safar, M.; Rajaei, E.; Haghighizadeh, M.H. Cinnamon Consumption Improves Clinical Symptoms and Inflammatory Markers in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, K. Turmeric: Potential Health Benefits. Nutr. Today 2020, 55, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Singh, A.; Jones, G.; Winzenberg, T.; Ding, C.; Chopra, A.; Das, S.; Danda, D.; Laslett, L.; Antony, B. Efficacy and Safety of Turmeric Extracts for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paultre, K.; Cade, W.; Hernandez, D.; Reynolds, J.; Greif, D.; Best, T.M. Therapeutic effects of turmeric or curcumin extract on pain and function for individuals with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e000935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqsa; Ali, S.; Summer, M.; Yousaf, S.; Nazakat, L.; Noor, S. Pharmacological and immunomodulatory modes of action of medically important phytochemicals against arthritis: A molecular insight. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasriadi, N.; Dasuni Wasana, P.W.; Vajragupta, O.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Towiwat, P. Mechanistic Insight into the Effects of Curcumin on Neuroinflammation-Driven Chronic Pain. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke-Okoro, U.J.; Raffa, R.B.; Pergolizzi, J.V., Jr.; Breve, F.; Taylor, R., Jr.; NEMA Research Group. Curcumin in turmeric: Basic and clinical evidence for a potential role in analgesia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 43, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkov, K.; Ackova, D.G.; Cvetkovski, A.; Ruskovska, T.; Vidovic, B.; Atalay, M. Piperine: Old Spice and New Nutraceutical? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atal, C.K.; Zutshi, U.; Rao, P.G. Scientific evidence on the role of Ayurvedic herbals on bioavailability of drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1981, 4, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johri, R.K.; Zutshi, U. An Ayurvedic formulation ’Trikatu’ and its constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1992, 37, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K. Black pepper and its pungent principle-piperine: A review of diverse physiological effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.K. The effects of black pepper on the intestinal absorption and hepatic metabolism of drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghwal, M.; Goswami, T.K. Piper nigrum and piperine: An update. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Sahebkar, A. Piperine and Its Role in Chronic Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 928, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Abbasi, B.H.; Fazal, H.; Khan, M.A.; Afridi, M.S. Effect of reverse photoperiod on in vitro regeneration and piperine production in Piper nigrum L. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2014, 337, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Levin, C.E.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, J.S.; Ohnisi-Kameyama, M.; Kozukue, N. Analysis by HPLC and LC/MS of pungent piperamides in commercial black, white, green, and red whole and ground peppercorns. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3028–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Patel, P.V. SurveySignal. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2014, 33, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, S.J.W.; Hasmi, L.; Drukker, M.; van Os, J.; Delespaul, P.A.E.G. Use of the experience sampling method in the context of clinical trials. BMJ Ment Health 2016, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, I.; Mertens, L.; Poppe, L.; Crombez, G.; Vetrovsky, T.; Van Dyck, D. The variability of emotions, physical complaints, intention, and self-efficacy: An ecological momentary assessment study in older adults. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngueleu, A.-M.; Barthod, C.; Best, K.L.; Routhier, F.; Otis, M.; Batcho, C.S. Criterion validity of ActiGraph monitoring devices for step counting and distance measurement in adults and older adults: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yeung, W.-T.M.; Kaye, J.A.; Beattie, Z. Step Count Standardization: Validation of Step Counts from the Withings Activite using PiezoRxD and wGT3X-BT. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) in conjunction with the 43rd Annual Conference of the Canadian Medical and Biological Engineering Society, Montreal, QC, Canada , 20–24 July 2020; pp. 4608–4611. [Google Scholar]

- Freedson, P.S.; Melanson, E.; Sirard, J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS® 9.4; SAS Institute Inc: Cary, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle, P.J.; Heagerty, P.J.; Liang, K.-y.; Zeger, S.L.; Diggle, P.J.; Heagerty, P.J.; Liang, K.-y.; Zeger, S.L. Analysis of variance methods. In Analysis of Longitudinal Data; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; p. 17-21, 114-125. [Google Scholar]

- Detry, M.A.; Ma, Y. Analyzing Repeated Measurements Using Mixed Models. JAMA 2016, 315, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J. Interpreting Outcomes 3-Clinical Meaningfulness: Linking Evidence to Practice. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euasobhon, P.; Atisook, R.; Bumrungchatudom, K.; Zinboonyahgoon, N.; Saisavoey, N.; Jensen, M.P. Reliability and responsivity of pain intensity scales in individuals with chronic pain. Pain 2022, 163, e1184–e1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; Beaton, D.; Cleeland, C.S.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Ader, D.N.; et al. Interpreting the Clinical Importance of Treatment Outcomes in Chronic Pain Clinical Trials: IMMPACT Recommendations. J. Pain 2008, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, F.; Braun, C.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Rittner, H.; Tian, Y.K.; Cai, X.Y.; Ye, D.W. Role of curcumin in the management of pathological pain. Phytomedicine 2018, 48, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Patchva, S.; Koh, W.; Aggarwal, B.B. Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its miraculous biological activities. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 39, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Girisa, S.; BharathwajChetty, B.; Vishwa, R.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Curcumin Formulations for Better Bioavailability: What We Learned from Clinical Trials Thus Far? ACS Omega 2023, 8, 10713–10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.Y. The spice for joint inflammation: Anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in treating osteoarthritis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 3029–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, K.R.; Golightly, Y.M. Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: Why and when. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 29, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, R.J.; Mullins, P.M.; Bhattacharyya, N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain 2021, 163, e328–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannes, C.B.; Le, T.K.; Zhou, X.; Johnston, J.A.; Dworkin, R.H. The Prevalence of Chronic Pain in United States Adults: Results of an Internet-Based Survey. J. Pain 2010, 11, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Variable | Baseline Data |

|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) [% of sample] | 27/2; [93.1%]/[6.9%] |

| Age (years) | 54.34 ± 6.8 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.31 ± 5.5 * |

| Overall baseline numeric pain ratings (scale: 0–10) | 4.3 ± 2.2 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Durham, L.; Oster, R.A.; Ithurburn, M.; Reynolds, C.; Hill, J.O.; Smith, D.L., Jr. Bioenhancer Assessment of Black Pepper with Turmeric on Self-Reported Pain Ratings in Adults: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2026, 18, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020223

Durham L, Oster RA, Ithurburn M, Reynolds C, Hill JO, Smith DL Jr. Bioenhancer Assessment of Black Pepper with Turmeric on Self-Reported Pain Ratings in Adults: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020223

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurham, Leandra, Robert A. Oster, Matthew Ithurburn, Chelsi Reynolds, James O. Hill, and Daniel L. Smith, Jr. 2026. "Bioenhancer Assessment of Black Pepper with Turmeric on Self-Reported Pain Ratings in Adults: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Clinical Trial" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020223

APA StyleDurham, L., Oster, R. A., Ithurburn, M., Reynolds, C., Hill, J. O., & Smith, D. L., Jr. (2026). Bioenhancer Assessment of Black Pepper with Turmeric on Self-Reported Pain Ratings in Adults: A Randomized, Cross-Over, Clinical Trial. Nutrients, 18(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020223