Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Aims of the Study

3. Materials and Methods

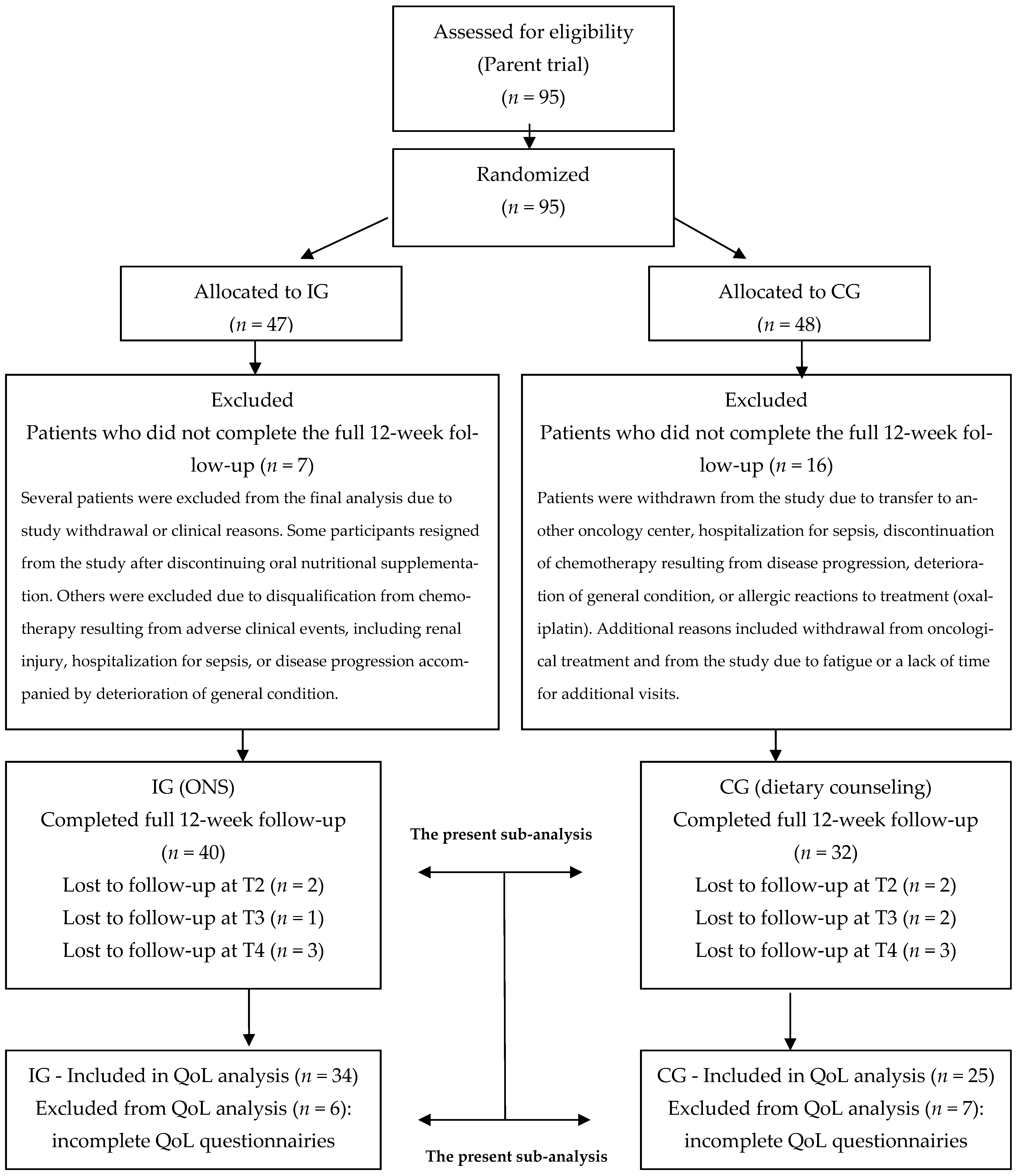

3.1. Relationship to Parent Study and Selection of QoL Subsample

3.2. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Histologically confirmed diagnosis of CRC, clinical stage II–IV according to TNM UICC 2010 [18].

- Eligibility for first-line chemotherapy according to regimens including: 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) or 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan (FOLFIRI), and other regimens; full chemotherapy dose (no dose reduction).

- Performance status ≥ 80% on the Karnofsky scale.

- Asymptomatic pre-cachexia associated with cancer, diagnosed according to the SCRINIO Working Group.

- No contraindications to oral nutrition and practical feasibility of oral feeding.

- No severe, uncontrolled comorbidities such as diabetes, liver failure, or renal failure (stage 2 according to KDOQI).

- Signed informed consent for participation.

3.4. Exclusion Criteria

- Diagnosis of malignant neoplasm in clinical stage I according to TNM UICC 2010 [18].

- Disqualification from oncological treatment.

- Overt cancer cachexia or anorexia–cachexia syndrome.

- Poor performance status—Karnofsky scale < 80% or WHO/ECOG 2–4.

- Contraindications to oral feeding or high-protein nutrition (e.g., liver or renal failure).

- Regular nutritional support at the time of study enrollment.

- Patient non-compliance at the time of study enrollment.

3.5. Quality of Life

3.5.1. FAACT

- Subscale scores are calculated by summing the item scores, multiplying by the number of items in the subscale, and dividing by the number of items answered.

- The Trial Outcome Index (TOI) is obtained by summing PWB, FWB, and ACS scores.

- The FACT-G total score is obtained by summing PWB, SWB, EWB, and FWB scores.

- The FAACT total score is obtained by summing PWB, SWB, EWB, FWB, and ACS scores.

3.5.2. Karnofsky Scale

3.5.3. Nutritional Status

- NRS-2002 includes three categories: impaired nutritional status (assessed by BMI, unintentional weight loss, and food intake relative to needs), disease severity, and age. A score ≥ 3 indicates nutritional risk and the need for nutritional intervention.

- SGA includes five categories: weight history, dietary intake, gastrointestinal symptoms, functional capacity, disease/comorbidities relative to nutritional needs, and physical examination. Each is rated on a 1–7 scale. Patients are classified as: well nourished (6–7), moderately malnourished (3–5), or severely malnourished (1–2).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

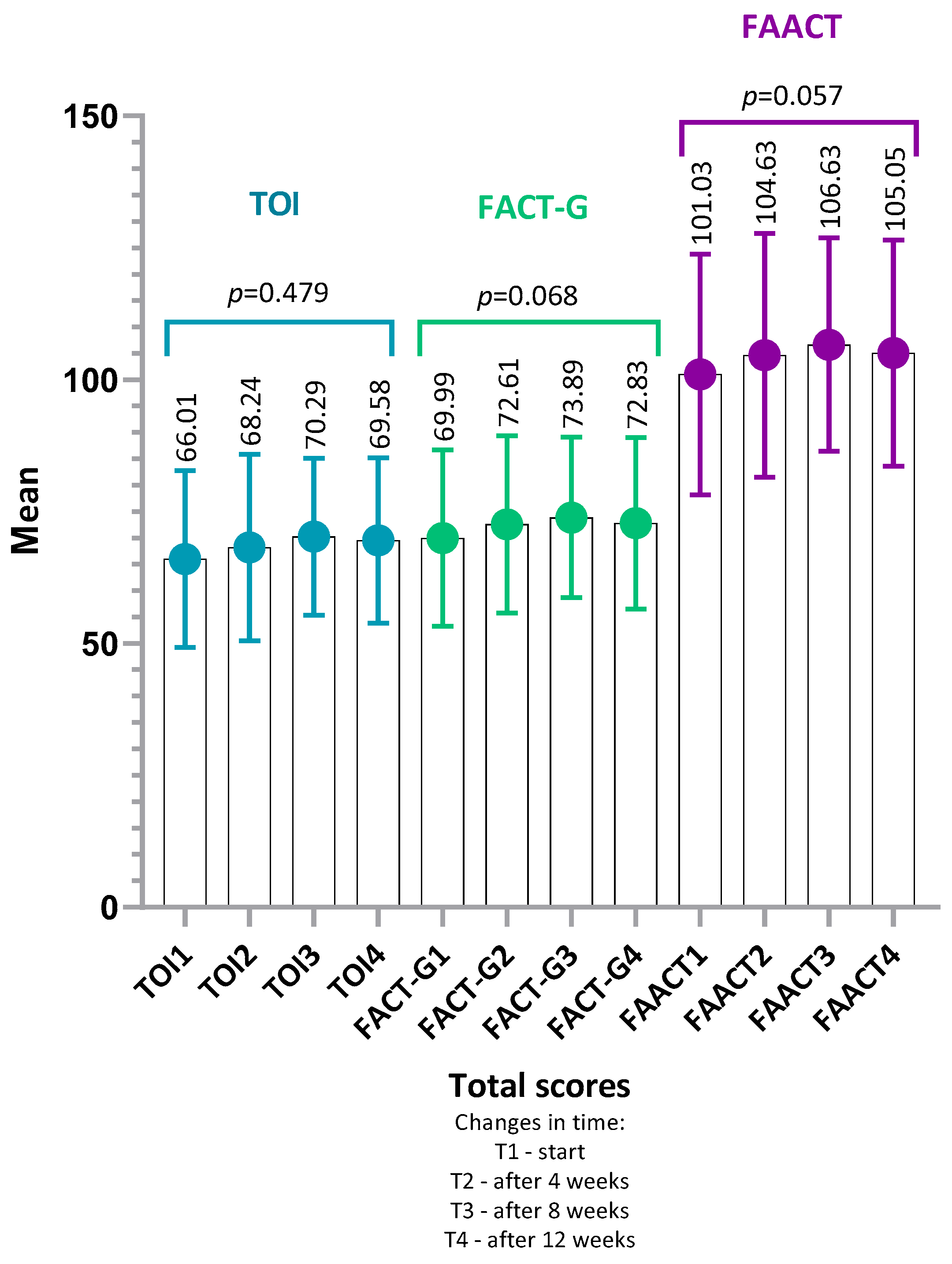

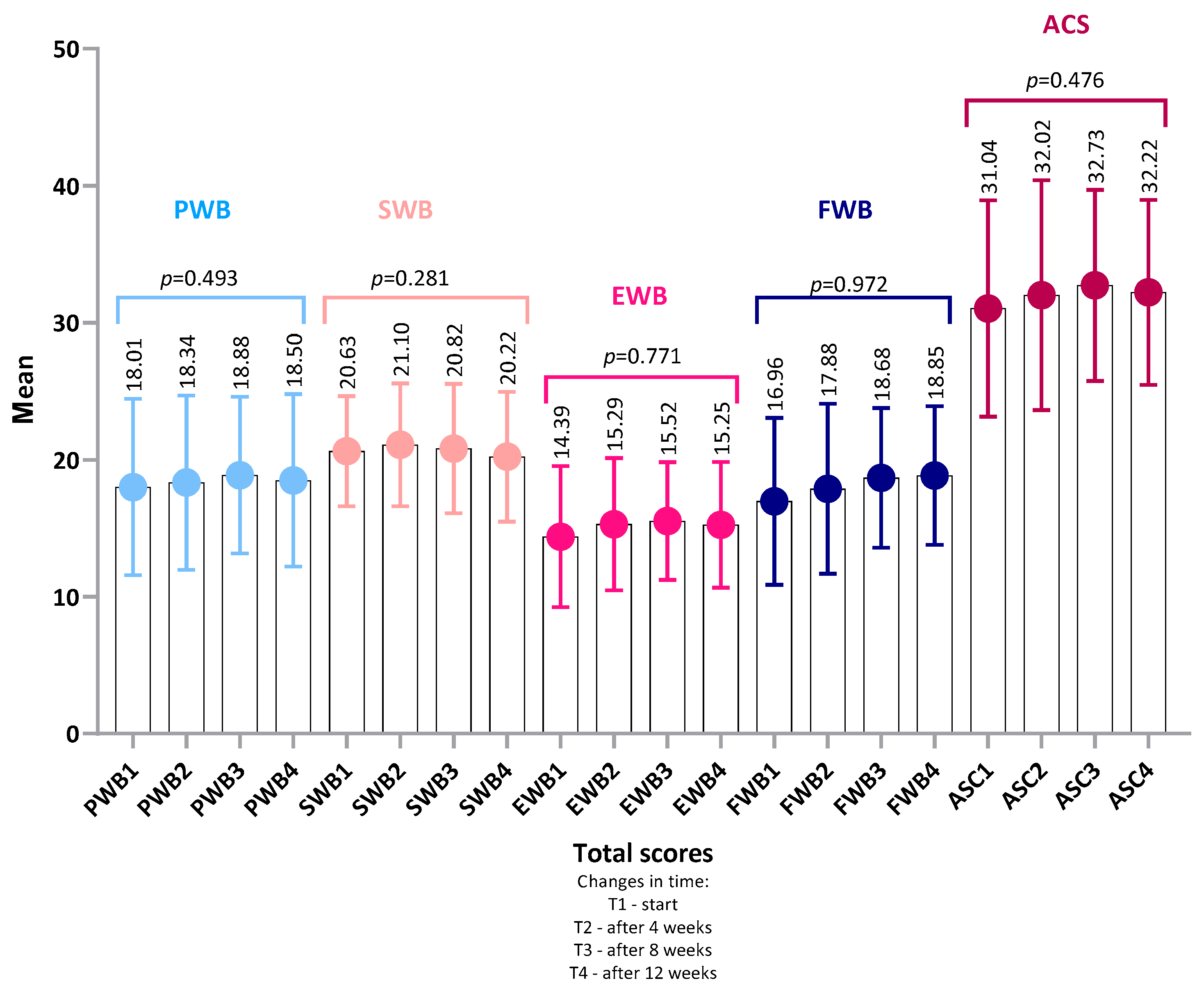

4.1. FAACT Results—Total Group

4.1.1. Analysis of Item-Level Results Within Each Category FAACT

4.1.2. Minimally Important Differences (MID)—FAACT

- FAACT (global score): improvement was significantly more frequent in IG (32%) than in CG (8%) (p = 0.03, OR = 5.50, 95% CI: 1.10–27.62, φ = 0.25).

- PWB (Physical Well-Being): improvement was significantly more frequent in IG (32%) than in CG (8%) (p = 0.03, OR = 5.50, 95% CI: 1.10–27.62, φ = 0.25).

- EWB (Emotional Well-Being): improvement was markedly more frequent in IG (38%) than in CG (4%) (p = 0.002, OR = 14.86, 95% CI: 1.79–123.36, φ = 0.36).

- In FWB, the proportion of improvement in IG (29%) was higher than in CG (8%), with results approaching significance (p = 0.05, OR = 4.79, 95% CI: 0.95–24.27, φ = 0.22).

- In ACS, deterioration was less frequent in IG (3%) compared with CG (20%), also reaching borderline significance (p = 0.07, OR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.01–1.11, φ = 0.22).

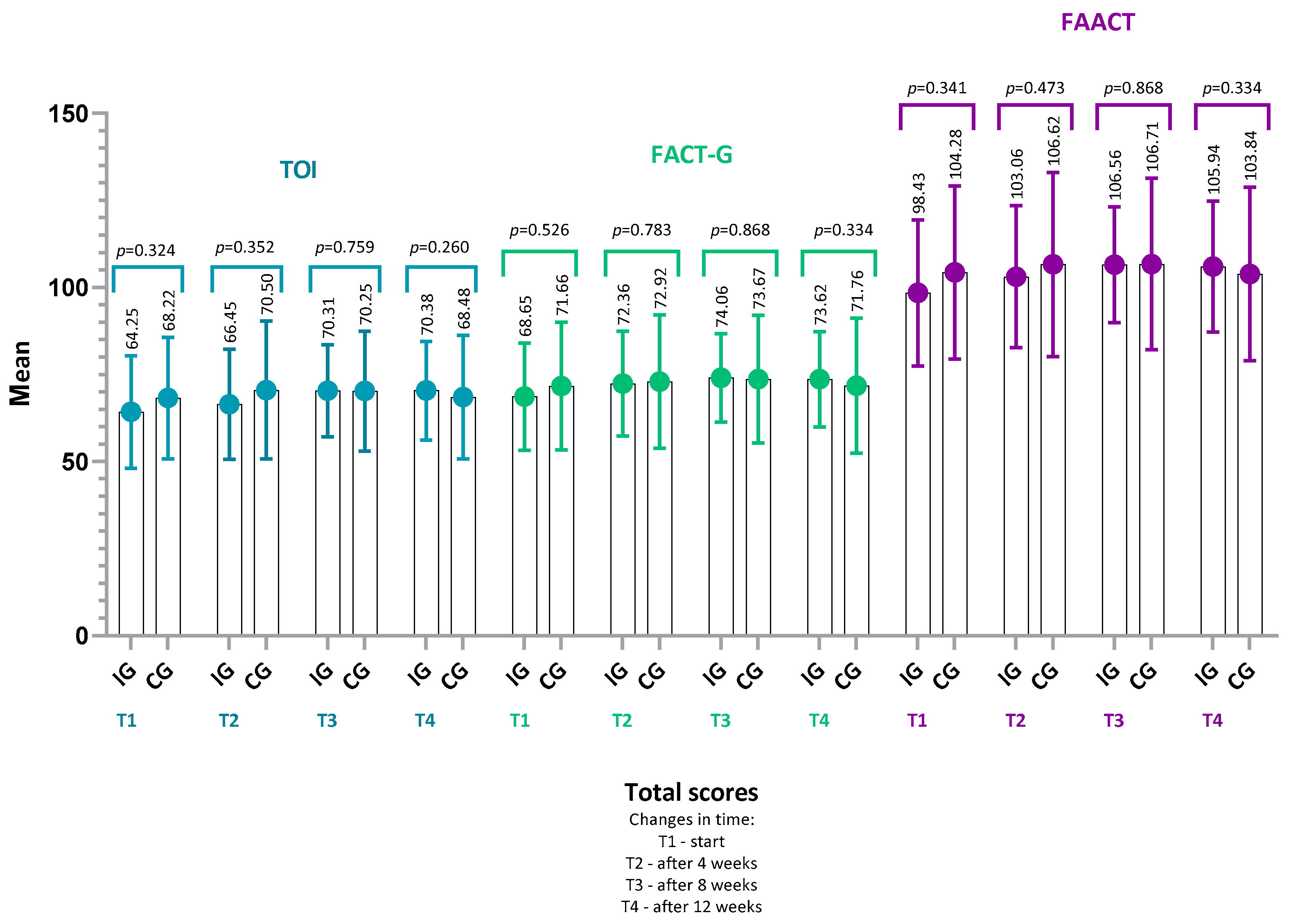

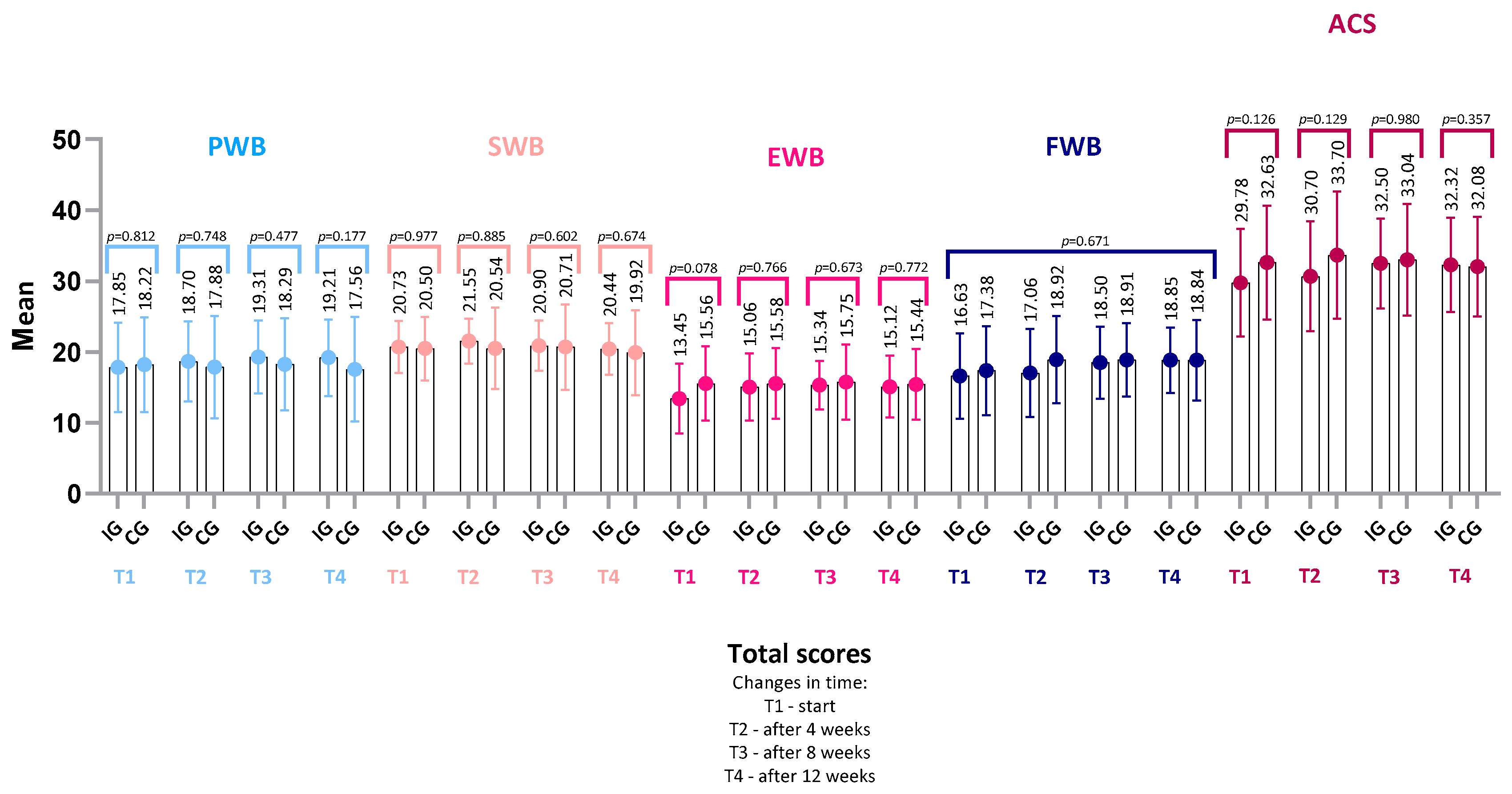

4.2. FAACT Results—IG vs. CG

- FACT-G score (IG: p = 0.22, r = 0.22; CG: p = 0.14, r = 0.30),

- TOI (Trial Outcome Index) (IG: p = 0.17, r = 0.24; CG: p = 0.29, r = 0.22),

- or in any of the FAACT subscales: PWB, SWB, EWB, FWB, ACS (all p > 0.05 for both groups).

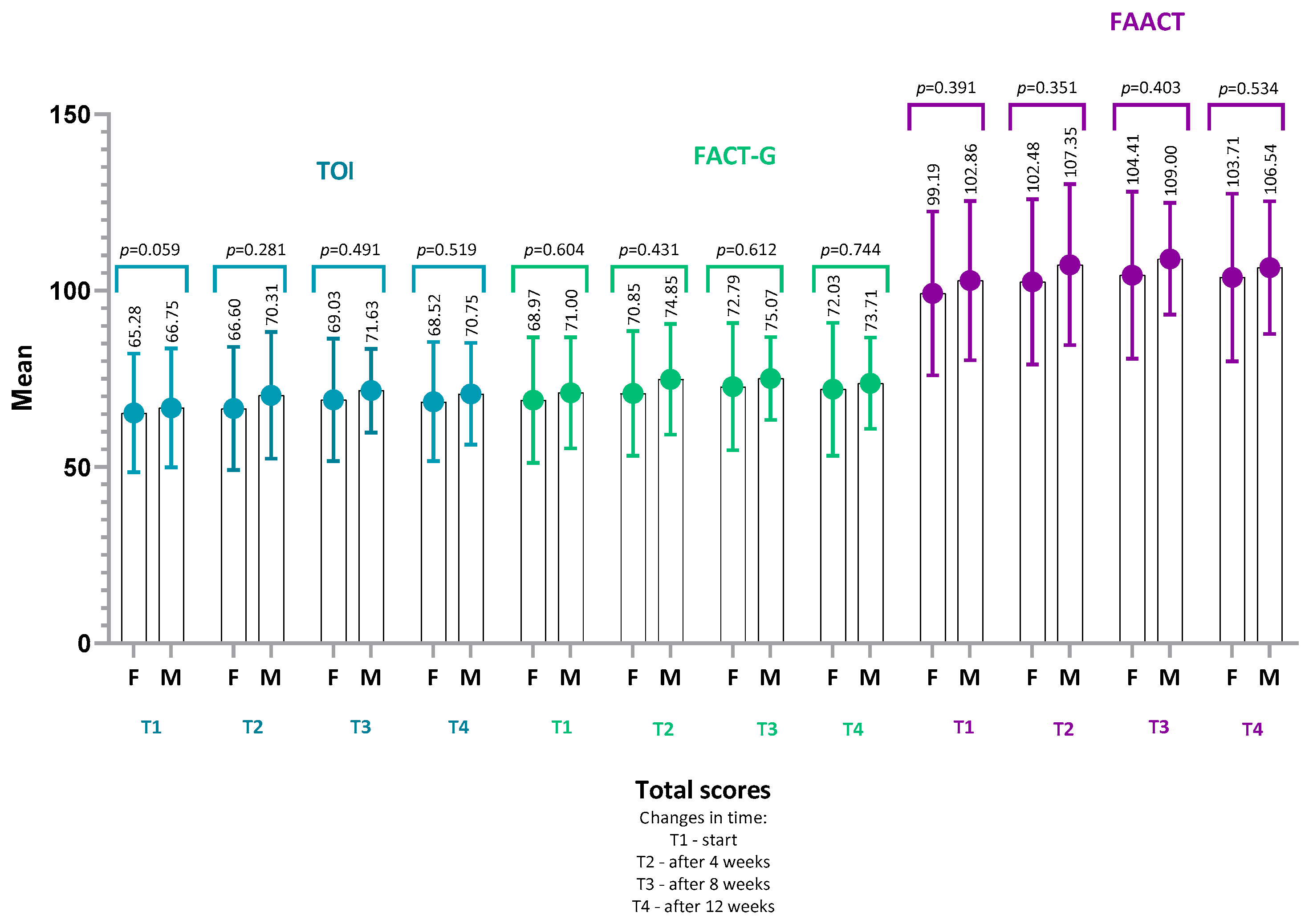

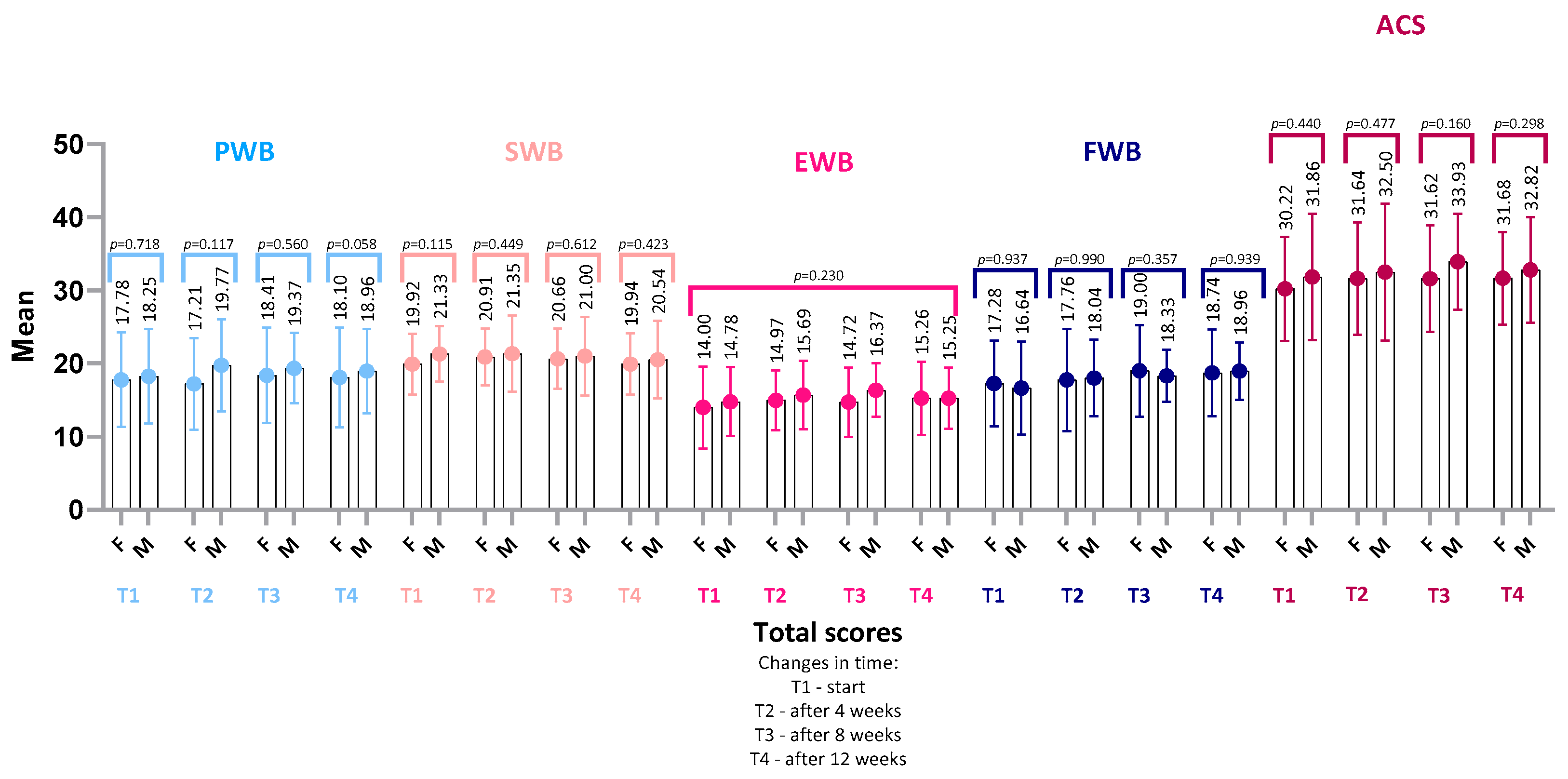

4.3. FAACT Results—Women vs. Men

4.4. Performance Status—Karnofsky Scale

4.5. Nutritional Status

4.6. The Association Between Quality of Life and Functional Performance, Nutritional Status and Appetite

4.6.1. Baseline (T1)—Overall Group

- The global FAACT score correlated positively with better nutritional status assessed by SGA (ρ = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.02–0.46, p = 0.03), higher functional performance (Karnofsky, ρ = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.11–0.52, p = 0.01), and better appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.29–0.65, p < 0.001).

- The FACT-G score was significantly associated with SGA (ρ = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.01–0.45, p = 0.04), functional performance (Karnofsky, ρ = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.01–0.45, p = 0.04), and appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.16–0.56, p < 0.001).

- TOI correlated positively with SGA (ρ = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.02–0.46, p = 0.03), Karnofsky (ρ = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.08–0.51, p = 0.01), and appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.29–0.65, p < 0.001).

- The ACS (anorexia–cachexia symptoms) was higher in patients with better nutritional status (SGA, ρ = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.00–0.44, p = 0.049), greater functional performance (Karnofsky, ρ = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.17–0.57, p < 0.001), and VAS (ρ = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.42–0.72, p < 0.001).

- Physical Well-Being (PWB) correlated positively with appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.14–0.55, p < 0.001) but negatively with NRS2002 (ρ = –0.28, 95% CI: −0.48–−0.05, p = 0.02), suggesting that malnutrition was associated with poorer physical functioning.

- Emotional Well-Being (EWB) correlated with functional performance (Karnofsky, ρ = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.07–0.50, p = 0.01) and appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.19–0.58, p < 0.001).

- Functional Well-Being (FWB) correlated positively with appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.05–0.48, p = 0.01).

- Social/Family Well-Being (SWB) correlated positively with appetite (VAS, ρ = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.04–0.47, p = 0.02).

4.6.2. End of Observation (T4)—Overall Group

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale (FAACT Additional Concerns) |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CG | Control Group |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Performance Status) |

| EWB | Emotional Well-Being |

| FAACT | Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy |

| FACT-G | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General |

| FOLFOX-4 | 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin regimen |

| FOLFIRI | 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan regimen |

| FWB | Functional Well-Being |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| IG | Intervention Group |

| KDOQI | Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative |

| KPS | Karnofsky Performance Status |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| MID | Minimally Important Difference |

| NRS-2002 | Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 |

| ONS | Oral Nutritional Supplements |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PWB | Physical Well-Being |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RR | Risk Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SGA | Subjective Global Assessment |

| SWB | Social/Family Well-Being |

| T1–T4 | Study Time Points: baseline and weeks 4, 8, and 12 |

| TNM (UICC) | Tumor–Node–Metastasis (Union for International Cancer Control) |

| TOI | Trial Outcome Index |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| XELOX | Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin Regimen |

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Gray, N.M.; Hall, S.J.; Browne, S.; Macleod, U.; Mitchell, E.; Lee, A.J.; Johnston, M.; Wyke, S.; Samuel, L.; Weller, D.; et al. Modifiable and fixed factors predicting quality of life in people with colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1697–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau, L.T.; Chan, S.W. Exploring the quality of life and the impact of the disease among patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev. 2011, 9, 2324–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, S.K.; Meng, X.; Youl, P.; Aitken, J.; Dunn, J.; Baade, P. A five-year prospective study of quality of life after colorectal cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1551–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, M.A.; Taal, B.G.; Aaronson, N.K.; te Velde, A. Quality of life in colorectal cancer. Stoma vs. nonstoma patients. Dis. Colon Rectum 1995, 38, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F.; Mariani, L. Defining and classifying cancer cachexia: A proposal by the SCRINIO Working Group. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2009, 33, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarricone, R.; Ricca, G.; Nyanzi-Wakholi, B.; Medina-Lara, A. Impact of cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome on health-related quality of life and resource utilisation: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 99, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, J.E.S.; Zapata, J.L.; Duarte, M.C.P.; Acevedo, V.V.; Calle, J.A.Z.; Montoya, A.R.; Cardona, L.S.G. Factors associated with quality of life among colorectal cancer patients: Cross-sectional study. Cancer Control 2024, 31, 10732748241302915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadis, D.; Giakoustidis, A.; Papadopoulos, V.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Watson, M. Quality of life, distress and psychological adjustment in patients with colon cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 68, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, O.; Mclauchlan, J.; McCombie, A.; Glyn, T.; Frizelle, F. Quality of life in early-onset colorectal cancer patients: Systematic review. BJS Open 2023, 7, zrad030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayers, P.; Machin, D. Quality of Life: The Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation of Patient-Reported Outcomes; John Wiley and sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tudela, L.L. Health-related quality of life. Aten. Primaria 2009, 41, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT). Available online: https://www.facit.org/measures/faact (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Orive, M.; Anton-Ladislao, A.; Lázaro, S.; Gonzalez, N.; Bare, M.; de Larrea, N.F.; Redondo, M.; Bilbao, A.; Sarasqueta, C.; Aguirre, U.; et al. Anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life, and mortality among colorectal patients: 5-year follow-up. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7943–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziętarska, M.; Krawczyk-Lipiec, J.; Kraj, L.; Zaucha, R.; Małgorzewicz, S. Chemotherapy-Related Toxicity, Nutritional Status and Quality of Life in Precachectic Oncologic Patients with, or without, High Protein Nutritional Support: A Prospective, Randomized Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobin, L.H.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 7th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FAACT English Downloads. Available online: https://www.facit.org/measure-english-downloads/faact-english-downloads (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- FAACT Scoring Downloads. Available online: https://www.facit.org/measures-scoring-downloads/faact-scoring-downloads (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1937, 32, 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K.X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, G.H.; Halton, J.H. Note on an exact treatment of contingency, goodness of fit and other problems of significance. Biometrika 1951, 38, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers, 5th ed.; Oliver and Boyd: Edinburgh, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Cella, D.; Hahn, E.A.; Dineen, K. Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Qual. Life Res. 2002, 11, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Note on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1927, 22, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika 1908, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauss, C.F. Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in Sectionibus Conicis Solem Ambientium; Perthes et Besser: Hamburg, Germany, 1809. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, J.L.; Lehmann, E.L. Estimates of location based on rank tests. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1955, 19, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fieller, E.C.; Hartley, H.O.; Pearson, E.S. Tests for rank correlation coefficients. I. Biometrika 1957, 44, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishara, A.J.; Hittner, J.B. Confidence intervals for correlations when data are not normal. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G.; Babington Smith, B. The problem of m rankings. Ann. Math. Stat. 1939, 10, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; Rosnow, R.L. Essentials of Behavioral Research: Methods and Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramér, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K.J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1990, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.; Cella, D.; Yost, K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhandiramge, J.; Orchard, S.G.; Warner, E.T.; van Londen, G.J.; Zalcberg, J.R. Functional decline in the cancer patient: A review. Cancers 2022, 14, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; Nipp, R.D.; Rushing, C.N.; Samsa, G.P.; Locke, S.C.; Kamal, A.H.; Cella, D.F.; Abernethy, A.P. Correlation between the international consensus definition of the Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome (CACS) and patient-centered outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.C.H.; von Meyenfeldt, M.F.; Moses, A.G.W.; van Geenen, R.; Roy, A.; Gouma, D.J.; Giacosa, A.; van Gossum, A.; Bauer, J.; Barber, M.D.; et al. Effect of a protein- and energy-dense n-3 fatty acid–enriched oral supplement on loss of weight and lean tissue in cancer cachexia: A randomised double-blind trial. Gut 2003, 52, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsso, C.E.; Caretero, A.; Scopel Poltronieri, T.; Arends, J.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Kiss, N.; Laviano, A.; Prado, C.M. Effects of high-protein supplementation during cancer therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 120, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, X.; He, Y.L.; Tian, Y.L.; Chen, T.L.; Yu, J.Y. Summary of evidence on nutritional management for patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauwhoff-Buskermolen, S.; Ruijgrok, C.; Ostelo, R.W.J.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Verheul, H.M.W.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Langius, J.A.E. The assessment of anorexia in patients with cancer: Cut-off values for the FAACT-A/CS and the VAS for appetite. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.; Kordatou, Z.; Barriuso, J.; Lamarca, A.; Weaver, J.; Cipriano, C.; Papaxoinis, G.; Backen, A.; Mansoor, W. Early recognition of anorexia through patient-generated assessment predicts survival in patients with oesophagogastric cancer. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.; Meng, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Xi, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Sui, X.; Wu, G. Impact of oral nutritional supplements in post-discharge patients at nutritional risk following colorectal cancer surgery: A randomised clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Spiro, A.; Ahern, R.; Emery, P.W. Oral nutritional interventions in malnourished patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa-nguansai, S.; Pintasiri, P.; Tienchaiananda, P. Efficacy of oral nutritional supplement in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Talebi, S.; Khosravinia, D.; Mohammadi, H. Oral nutritional supplementation in cancer patients: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 47, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.S.; Chang, V.T.; Fairclough, D.L.; Cogswell, J.; Kasimis, B. Longitudinal quality of life in advanced cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2003, 25, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, L.A.; Nuzzo, M.; Rosa, C.; DI Guglielmo, F.C.; DI Tommaso, M.; Trignani, M.; Borgia, M.; Allajbej, A.; Patani, F.; DI Carlo, C.; et al. Quality of life in early breast cancer patients: A prospective observational study using the FACT-B questionnaire. Vivo 2021, 35, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharour, L.A.; Omari, O.A.I.; Salameh, A.B.; Yehia, D. Health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 25, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribaudo, J.; Cella, D.; Hahn, E.; Lloyd, S.; Tchekmedyian, N.; Von Roenn, J.; Leslie, W. Re-validation and shortening of the Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. 2000, 9, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, C.R.C.; Bergmann, A.; Lima, J.T.d.O.; Lima, W.R.P.; de Britto, M.C.; de Mello, M.J.G.; Thuler, L.C.S. Prospective analysis of health-related quality of life in older adults with cancer. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esbensen, B.A.; Osterlind, K.; Hallberg, I.R. Quality of life of elderly persons with cancer: A 6-month follow-up. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2007, 21, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghousi, D.; Jafari, E.; Nikbakht, H.; Nasiri, B.; Shamshirgaran, M.; Aminisani, N. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019, 10, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Gender differences in psychosocial outcomes and coping strategies of patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | IG (N = 40) | CG (N = 32) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 72.62 ± 10.56 | 71.28 ± 11.68 | 0.639 |

| Sex, female/male, n | 17/23 | 19/13 | 0.155 |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | G2: 34 (85%) G3: 4 (10%) G4: 2 (5%) | G2: 29 (90.6%) G3: 3 (9.4%) G4: 0 (0%) | 0.305 |

| Metastases, n (%) | 34 (85%) | 31 (97%) | 0.096 |

| Colostomy, n (%) | 21 (52.5%) | 6 (18.75%) | 0.003 |

| Chemotherapy regimen, n (%) | FOLFOX: 14 (35%) FOLFIRI: 4 (10%) Other: 22 (55%) | FOLFOX: 10 (31.3%) FOLFIRI: 5 (15.6%) Other: 17 (53.1%) | 0.765 |

| SD T1 | MID 0.5 × SD | MID+ * (n) | MID− ** (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAACT | 22.82 | 11.41 | 13 | 8 |

| FACT-G | 16.70 | 8.35 | 14 | 8 |

| PWB | 6.44 | 3.22 | 13 | 10 |

| SWB | 4.03 | 2.01 | 10 | 11 |

| EWB | 5.15 | 2.57 | 14 | 8 |

| FWB | 6.10 | 3.05 | 12 | 4 |

| ACS | 7.89 | 3.95 | 16 | 6 |

| Scale | Outcome | CG (n = 25) | IG (n = 34) | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | φ | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAACT | Improvement | 2/25 | 11/34 | 0.03 | 5.5 | [1.1, 27.62] | 0.29 | Improvement is significantly more common in IG |

| FAACT | Deterioration | 3/25 | 5/34 | 1.0 | 1.26 | [0.27, 5.87] | 0.04 | |

| FACT-G | Improvement | 5/25 | 9/34 | 0.76 | 1.44 | [0.42, 4.98] | 0.08 | No significant differences |

| FACT-G | Deterioration | 4/25 | 4/34 | 0.71 | 0.7 | [0.16, 3.12] | 0.06 | |

| PWB | Improvement | 2/25 | 11/34 | 0.03 | 5.5 | [1.1, 27.62] | 0.29 | Improvement is significantly more common in IG |

| PWB | Deterioration | 6/25 | 4/34 | 0.30 | 0.42 | [0.11, 1.69] | 0.16 | |

| SWB | Improvement | 5/25 | 5/34 | 0.73 | 0.69 | [0.18, 2.7] | 0.07 | No significant differences |

| SWB | Deterioration | 6/25 | 5/34 | 0.50 | 0.55 | [0.15, 2.04] | 0.12 | |

| EWB | Improvement | 1/25 | 13/34 | 0.002 | 14.86 | [1.79, 123.36] | 0.40 | Improvement is significantly more common in IG |

| EWB | Deterioration | 5/25 | 3/34 | 0.26 | 0.39 | [0.08, 1.8] | 0.16 | |

| FWB | Improvement | 2/25 | 10/34 | 0.05 | 4.79 | [0.95, 24.27] | 0.26 | No significant differences |

| FWB | Deterioration | 2/25 | 2/34 | 1.00 | 0.72 | [0.09, 5.48] | 0.04 | |

| ACS | Improvement | 6/25 | 10/34 | 0.77 | 1.32 | [0.41, 4.28] | 0.06 | No significant differences |

| ACS | Deterioration | 5/25 | 1/34 | 0.07 | 0.12 | [0.01, 1.11] | 0.28 |

| KPS Overall Group | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 | 1 (1.4%, 0.2–7.5%) | 1 (1.5%, 0.3–8.0%) | 1 (1.7%, 0.3–8.9%) | 0 (0.0%, 0.0–6.1%) |

| 80 | 8 (11.1%, 5.7–20.4%) | 7 (10.4%, 5.2–20.0%) | 8 (13.3%, 6.9–24.2%) | 8 (13.6%, 7.0–24.5%) |

| 90 | 38 (52.8%, 41.4–63.9%) | 36 (53.7%, 41.9–65.1%) | 30 (50.0%, 37.7–62.3%) | 31 (52.5%, 40.0–64.7%) |

| 100 | 25 (34.7%, 24.8–46.2%) | 23 (34.3%, 24.1–46.3%) | 21 (35.0%, 24.2–47.6%) | 20 (33.9%, 23.1–46.6%) |

| Group | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | p-Value 1 | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 92.08 ± 6.91 | 92.09 ± 6.86 | 91.67 ± 7.85 | 92.04 ± 6.64 | 0.37 | 0.02 |

| (90.25–93.91) | (90.27–93.91) | (89.59–93.75) | (90.28–93.80) | |||

| 90 (70–100) | 90 (70–100) | 90 (60–100) | 90 (80–100) | |||

| CG | 93.75 ± 6.09 | 94.14 ± 5.68 | 93.60 ± 5.68 | 92.50 ± 6.76 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| (91.24–96.26) | (91.80–96.48) | (91.26–95.94) | (89.71–95.29) | |||

| 90 (80–100) | 90 (80–100) | 90 (80–100) | 90 (80–100) | |||

| IG | 90.75 ± 7.30 | 90.53 ± 7.33 | 90.29 ± 8.57 | 91.71 ± 6.64 | 0.52 | 0.02 |

| (88.12–93.38) | (87.89–93.17) | (87.20–93.38) | (89.32–94.10) | |||

| 90 (70–100) | 90 (70–100) | 90 (70–100) | 90 (80–100) | |||

| p-value 2 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.65 | ||

| r | 0.23 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.06 | ||

| (CG vs. IG) |

| BMI Category | n | PWB | SWB | EWB | FWB | ACS | FACT-G | TOI | FAACT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤18.9 | 7 | 13.43 ± 5.68 CI: 8.18–18.68 15.00 (5.00–20.00) | 18.86 ± 3.08 CI: 16.01–21.71 18.00 (14.00–24.00) | 13.14 ± 2.73 CI: 10.62–15.66 12.00 (10.00–18.00) | 14.86 ± 4.38 CI: 10.81–18.91 14.00 (9.00–21.00) | 26.43 ± 6.02 CI: 20.86–32.00 25.00 (19.00–36.00) | 60.29 ± 10.44 CI: 50.63–69.95 57.00 (45.00–75.00) | 54.71 ± 14.23 CI: 41.55–67.87 52.00 (37.00–76.00) | 86.71 ± 15.61 CI: 72.27–101.15 81.00 (70.00–109.00) |

| >18.9–24.9 | 31 | 19.23 ± 5.73 CI: 17.13–21.33 20.00 (6.00–28.00) | 20.48 ± 4.16 CI: 18.95–22.01 21.00 (9.00–28.00) | 14.97 ± 4.81 CI: 13.21–16.73 16.00 (3.00–24.00) | 16.68 ± 6.14 CI: 14.43–18.93 16.00 (0.00–28.00) | 31.10 ± 6.79 CI: 28.61–33.59 31.00 (17.00–44.00) | 71.35 ± 15.91 CI: 65.51–77.19 71.00 (29.00–108.00) | 67.00 ± 14.92 CI: 61.53–72.47 65.00 (41.00–100.00) | 102.45 ± 20.67 CI: 94.87–110.03 100.00 (56.00–152.00) |

| ≥25–29.9 | 24 | 17.92 ± 7.48 CI: 14.76–21.08 19.00 (5.00–28.00) | 21.33 ± 4.35 CI: 19.49–23.17 23.50 (11.00–28.00) | 13.25 ± 6.44 CI: 10.53–15.97 13.00 (0.00–24.00) | 17.12 ± 6.96 CI: 14.18–20.06 16.50 (1.00–28.00) | 32.83 ± 9.05 CI: 29.01–36.65 31.50 (15.00–48.00) | 69.62 ± 19.58 CI: 61.35–77.89 67.00 (32.00–103.00) | 67.88 ± 18.91 CI: 59.90–75.86 65.00 (39.00–104.00) | 102.46 ± 26.89 CI: 91.11–113.81 100.00 (57.00–151.00) |

| ≥30 | 10 | 17.70 ± 5.62 CI: 13.68–21.72 18.00 (8.00–24.00) | 20.60 ± 3.41 CI: 18.16–23.04 19.50 (16.00–26.00) | 16.20 ± 3.39 CI: 13.77–18.63 15.50 (11.00–21.00) | 18.90 ± 4.84 CI: 15.44–22.36 19.50 (11.00–27.00) | 29.80 ± 8.80 CI: 23.50–36.10 29.00 (14.00–43.00) | 73.40 ± 14.58 CI: 62.97–83.83 72.50 (48.00–94.00) | 66.40 ± 17.44 CI: 53.92–78.88 66.50 (33.00–94.00) | 103.20 ± 22.24 CI: 87.29–119.11 102.00 (62.00–137.00) |

| p-value 1 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.83 | 0.64 | |

| η2 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| BMI Category | n | PWB | SWB | EWB | FWB | ACS | FACT-G | TOI | FAACT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤18.9 | 3 | 16.33 ± 6.11 CI: −4.61–37.27 15.00 (11.00–23.00) | 19.33 ± 4.16 CI: 8.86–29.80 18.00 (16.00–24.00) | 12.67 ± 6.43 CI: −9.53–34.87 10.00 (8.00–20.00) | 15.67 ± 4.73 CI: 3.37–27.97 14.00 (12.00–21.00) | 24.00 ± 4.00 CI: 14.00–34.00 24.00 (20.00–28.00) | 64.00 ± 21.38 CI: −5.74–133.74 57.00 (47.00–88.00) | 56.00 ± 14.73 CI: 12.50–99.50 53.00 (43.00–72.00) | 88.00 ± 25.24 CI: 6.30–169.70 81.00 (67.00–116.00) |

| >18.9–24.9 | 26 | 18.50 ± 6.10 CI: 16.04–20.96 19.50 (4.00–28.00) | 20.23 ± 4.34 CI: 18.44–22.02 20.00 (10.00–28.00) | 14.85 ± 4.24 CI: 13.14–16.56 15.00 (6.00–24.00) | 18.42 ± 5.02 CI: 16.40–20.44 17.50 (8.00–28.00) | 31.31 ± 7.46 CI: 28.30–34.32 32.50 (16.00–48.00) | 72.00 ± 15.84 CI: 65.61–78.39 72.50 (28.00–107.00) | 68.23 ± 15.73 CI: 61.88–74.58 70.50 (41.00–103.00) | 103.31 ± 21.45 CI: 94.65–111.97 104.50 (57.00–155.00) |

| ≥25–29.9 | 19 | 18.21 ± 6.91 CI: 14.88–21.54 18.00 (6.00–28.00) | 21.16 ± 4.00 CI: 19.34–22.98 22.00 (14.00–28.00) | 15.47 ± 5.21 CI: 12.96–17.98 15.00 (6.00–24.00) | 19.16 ± 5.79 CI: 16.37–21.95 21.00 (6.00–28.00) | 34.00 ± 5.93 CI: 31.14–36.86 32.00 (25.00–44.00) | 74.00 ± 18.98 CI: 64.83–83.17 72.00 (38.00–104.00) | 71.37 ± 16.66 CI: 63.33–79.41 72.00 (40.00–99.00) | 108.00 ± 23.86 CI: 97.17–118.83 104.00 (66.00–147.00) |

| ≥30 | 11 | 19.64 ± 6.39 CI: 15.35–23.93 19.00 (6.00–28.00) | 18.82 ± 6.85 CI: 13.91–23.73 20.00 (1.00–28.00) | 16.55 ± 4.03 CI: 13.85–19.25 16.00 (12.00–24.00) | 20.18 ± 3.79 CI: 17.64–22.72 20.00 (15.00–28.00) | 33.55 ± 5.26 CI: 30.02–37.08 32.00 (26.00–40.00) | 75.18 ± 11.21 CI: 67.66–82.70 71.00 (64.00–103.00) | 73.36 ± 13.44 CI: 64.33–82.39 71.00 (55.00–96.00) | 108.73 ± 15.34 CI: 98.44–119.02 102.00 (91.00–143.00) |

| p-value 1 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.93 | |

| η2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ziętarska, M.; Małgorzewicz, S. Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy. Nutrients 2026, 18, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020191

Ziętarska M, Małgorzewicz S. Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020191

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiętarska, Monika, and Sylwia Małgorzewicz. 2026. "Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020191

APA StyleZiętarska, M., & Małgorzewicz, S. (2026). Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy. Nutrients, 18(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020191