Maternal Determinants of Human Milk Leptin and Their Associations with Neonatal Growth Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.2. Leptin Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Linear Regression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

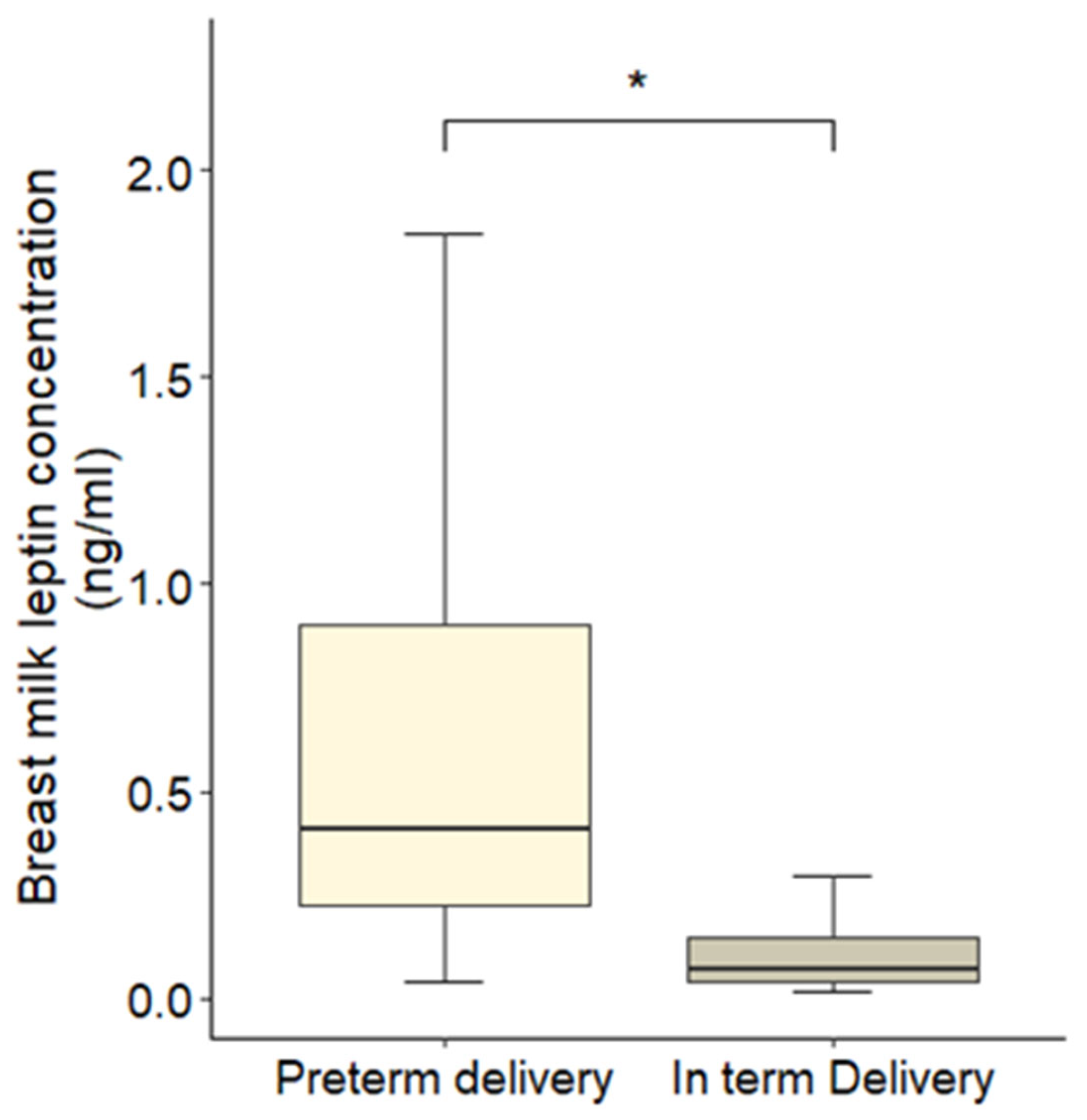

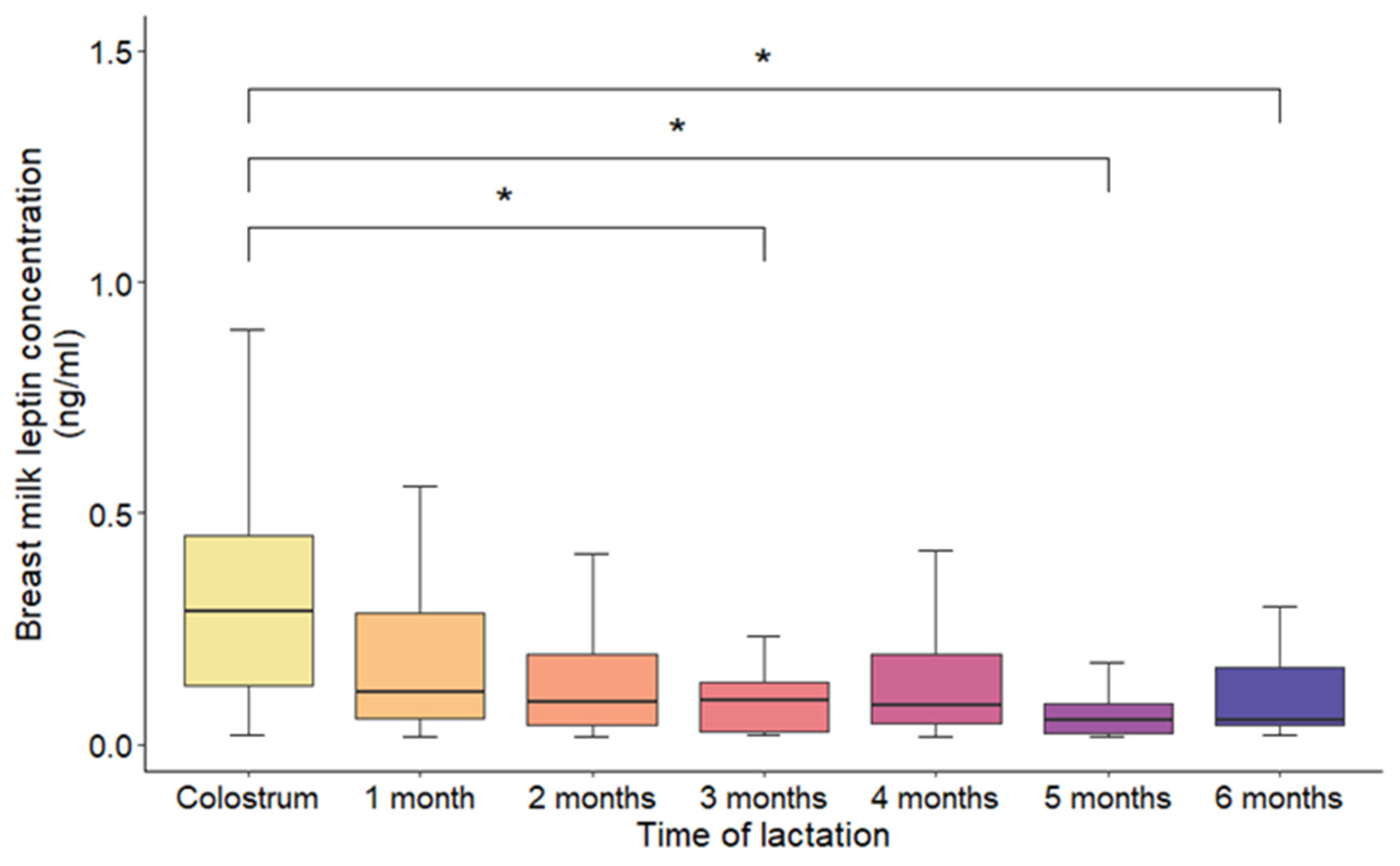

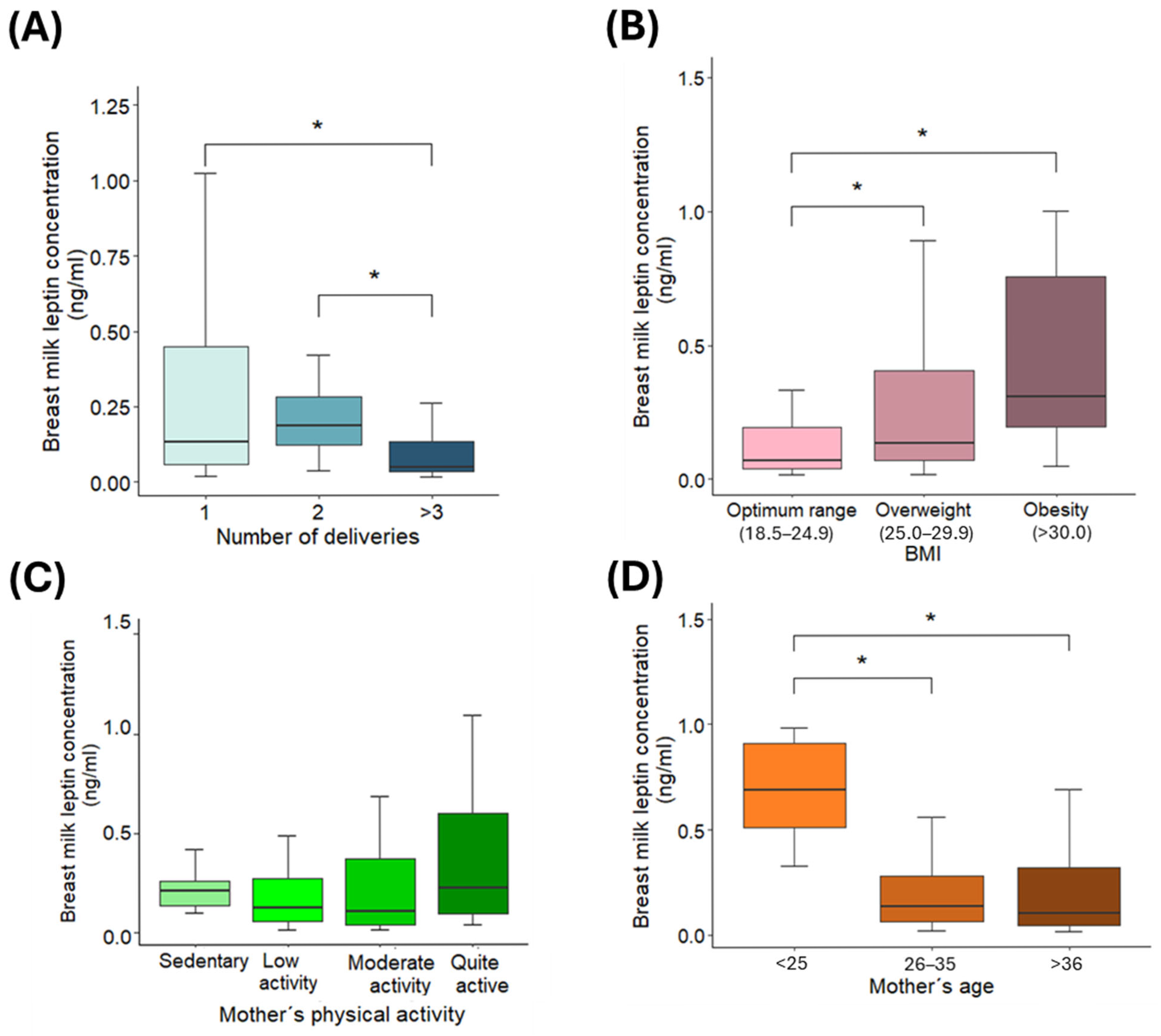

3.2. Variations in Leptin Concentrations

3.3. Linear Regression Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBM | Human Breast Milk |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

Appendix A

| Predictor Variable | Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF) | Degrees of Freedom (df) | GVIF1/(2·df) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.05 | 1 | 1.02 |

| Physical activity | 1.20 | 3 | 1.03 |

| Delivery type (term/preterm) | 1.15 | 1 | 1.07 |

References

- Lönnerdal, B. Breast Milk: A Truly Functional Food. Nutrition 2000, 16, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delplanque, B.; Gibson, R.; Koletzko, B.; Lapillonne, A.; Strandvik, B. Lipid Quality in Infant Nutrition: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prell, C.; Koletzko, B. Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.R.; Ling, P.R.; Blackburn, G.L. Review of Infant Feeding: Key Features of Breast Milk and Infant Formula. Nutrients 2016, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwolińska, D.; Namieśnik, J.; Kot-Wasik, A.; Hewelt-Belka, W. Chemistry of Human Breast Milk-A Comprehensive Review of the Composition and Role of Milk Metabolites in Child Development. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 11881–11896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, O.; Morrow, A.L. Human Milk Composition: Nutrients and Bioactive Factors. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, L.E.; Virmani, M.D.; Rosa, F.; Munblit, D.; Matazel, K.S.; Elolimy, A.A.; Yeruva, L. Role of Human Milk Bioactives on Infants’ Gut and Immune Health. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 604080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, O.M.; Gavrieli, A.; Mantzoros, C.S. Leptin Applications in 2015: What Have We Learned about Leptin and Obesity? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2015, 22, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Soskic, S.; Essack, M.; Arya, S.; Stewart, A.J.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Leptin and Obesity: Role and Clinical Implication. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 585887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkiewicz-Darol, E.; Adamczyk, I.; Łubiech, K.; Pilarska, G.; Twarużek, M. Leptin in Human Milk-One of the Key Regulators of Nutritional Programming. Molecules 2022, 27, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, M.; Considine, R.V.; Van Gaal, L.F. Human Leptin: From an Adipocyte Hormone to an Endocrine Mediator. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2000, 143, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houseknecht, K.L.; Baile, C.A.; Matteri, R.L.; Spurlock, M.E. The Biology of Leptin: A Review. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Zhao, S.; Garvey, W.T. Leptin, An Adipokine With Central Importance in the Global Obesity Problem. Glob. Heart 2018, 13, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, R.; Fewtrell, M.; Wells, J.C.K.; Dib, S. The Association between Maternal Factors and Milk Hormone Concentrations: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1390232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, O.; Sánchez, J.; Palou, A.; Picó, C. A Physiological Role of Breast Milk Leptin in Body Weight Control in Developing Infants. Obesity 2006, 14, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseknecht, K.L.; McGuire, M.K.; Portocarrero, C.P.; McGuire, M.A.; Beerman, K. Leptin Is Present in Human Milk and Is Related to Maternal Plasma Leptin Concentration and Adiposity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 240, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, F.K.; Önal, E.E.; Aral, Y.Z.; Adam, B.; Dilmen, U.; Ardiçolu, Y. Breast Milk Leptin: Its Relationship to Maternal and Infant Adiposity. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 21, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, E.A.; Largado, F.; Borja, J.B.; Kuzawa, C.W. Maternal Characteristics Associated with Milk Leptin Content in a Sample of Filipino Women and Associations with Infant Weight for Age. J. Hum. Lact. 2015, 31, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, C.A.; Koenig, W.; Rothenbacher, D.; Genuneit, J. Determinants of Leptin in Human Breast Milk: Results of the Ulm SPATZ Health Study. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez Lleó, C.I.; Soler, C.; Soriano, J.M.; San Onofre, N. CastelLact Project: Exploring the Nutritional Status and Dietary Patterns of Pregnant and Lactating Women-A Comprehensive Evaluation of Dietary Adequacy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Fente, C.; Barreiro, R.; López-Racamonde, O.; Cepeda, A.; Regal, P. Association between Breast Milk Mineral Content and Maternal Adherence to Healthy Dietary Patterns in Spain: A Transversal Study. Foods 2020, 9, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramiro-Cortijo, D.; Herranz Carrillo, G.; Singh, P.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; Ruvira, S.; Martín-Trueba, M.; Martin, C.R.; Arribas, S.M. Maternal and Neonatal Factors Modulating Breast Milk Cytokines in the First Month of Lactation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuzaki, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Sagawa, N.; Hosoda, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Mise, H.; Nishimura, H.; Yoshimasa, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Mori, T.; et al. Nonadipose Tissue Production of Leptin: Leptin as a Novel Placenta-Derived Hormone in Humans. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabiell, X.; Piñeiro, V.; Tomé, M.A.; Peinó, R.; Diéguez, C.; Casanueva, F.F. Presence of Leptin in Colostrum and/or Breast Milk from Lactating Mothers: A Potential Role in the Regulation of Neonatal Food Intake. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 4270–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, S.; Hechler, C.; Gebauer, C.; Kiess, W.; Kratzsch, J. Leptin in Maternal Serum and Breast Milk: Association with Infants’ Body Weight Gain in a Longitudinal Study over 6 Months of Lactation. Pediatr. Res. 2011, 70, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D.A.; Demerath, E.W. Relationship of Insulin, Glucose, Leptin, IL-6 and TNF-α in Human Breast Milk with Infant Growth and Body Composition. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, N.J.; Hyde, M.J.; Gale, C.; Parkinson, J.R.C.; Jeffries, S.; Holmes, E.; Modi, N. Effect of Maternal Body Mass Index on Hormones in Breast Milk: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D.A.; George, B.; Williams, M.; Whitaker, K.; Allison, D.B.; Teague, A.; Demerath, E.W. Associations between Human Breast Milk Hormones and Adipocytokines and Infant Growth and Body Composition in the First 6 Months of Life. Pediatr. Obes. 2017, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, N.J.; Kampmann, B.; Mehring Le-Doare, K. Human Breast Milk: A Review on Its Composition and Bioactivity. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, F.; Liguori, S.A.; Fissore, M.F.; Oggero, R. Breast Milk Hormones and Their Protective Effect on Obesity. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2009, 2009, 327505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J.; Woo, J.G.; Geraghty, S.R.; Altaye, M.; Davidson, B.S.; Banach, W.; Dolan, L.M.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Morrow, A.L. Adiponectin Is Present in Human Milk and Is Associated with Maternal Factors. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróblewski, A.; Strycharz, J.; Świderska, E.; Drewniak, K.; Drzewoski, J.; Szemraj, J.; Kasznicki, J.; Śliwińska, A. Molecular Insight into the Interaction between Epigenetics and Leptin in Metabolic Disorders. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielicki, J.; Huch, R.; von Mandach, U. Time-Course of Leptin Levels in Term and Preterm Human Milk. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 151, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilers, E.; Ziska, T.; Harder, T.; Plagemann, A.; Obladen, M.; Loui, A. Leptin Determination in Colostrum and Early Human Milk from Mothers of Preterm and Term Infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2011, 87, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resto, M.; O’Connor, D.; Leef, K.; Funanage, V.; Spear, M.; Locke, R. Leptin Levels in Preterm Human Breast Milk and Infant Formula. Pediatrics 2001, 108, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatmethakul, T.; Schmelzel, M.L.; Johnson, K.J.; Walker, J.R.; Santillan, D.A.; Colaizy, T.T.; Roghair, R.D. Postnatal Leptin Levels Correlate with Breast Milk Leptin Content in Infants Born before 32 Weeks Gestation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsky, J.; Mitrova, K.; Karpisek, M.; Mazoch, J.; Durilova, M.; Fisarkova, B.; Stechova, K.; Prusa, R.; Nevoral, J. Adiponectin, AFABP, and Leptin in Human Breast Milk during 12 Months of Lactation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilcol, Y.O.; Hizli, Z.B.; Ozkan, T. Leptin Concentration in Breast Milk and Its Relationship to Duration of Lactation and Hormonal Status. Int. Breastfeed J. 2006, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkiewicz-Darol, E.; Łubiech, K.; Adamczyk, I. Influence of Lactation Stage on Content of Neurotrophic Factors, Leptin, and Insulin in Human Milk. Molecules 2024, 29, 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, X.; Mu, Y.; Chen, P.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dai, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; et al. Maternal Characteristics and Prevalence of Infants Born Small for Gestational Age. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2429434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Goruk, S.; Becker, A.B.; Subbarao, P.; Mandhane, P.J.; Turvey, S.E.; Lefebvre, D.; Sears, M.R.; Field, C.J.; Azad, M.B. Adiponectin, Leptin and Insulin in Breast Milk: Associations with Maternal Characteristics and Infant Body Composition in the First Year of Life. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Cui, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, L. Association between Maternal Metabolic Profiles in Pregnancy, Dietary Patterns during Lactation and Breast Milk Leptin: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyermann, M.; Brenner, H.; Rothenbacher, D. Adipokines in Human Milk and Risk of Overweight in Early Childhood: A Prospective Cohort Study. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, I.Y.; Shilina, N.M.; Gmoshinskaya, M.V.; Ivanushkina, T.A. The Study of Breast Milk IGF-1, Leptin, Ghrelin and Adiponectin Levels as Possible Reasons of High Weight Gain in Breast-Fed Infants. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 65, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.M.; Brei, C.; Stecher, L.; Much, D.; Brunner, S.; Hauner, H. The Relationship between Breast Milk Leptin and Adiponectin with Child Body Composition from 3 to 5 Years: A Follow-up Study. Pediatr. Obes. 2017, 12, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, S.; Schmid, D.; Zang, K.; Much, D.; Knoeferl, B.; Kratzsch, J.; Amann-Gassner, U.; Bader, B.L.; Hauner, H. Breast Milk Leptin and Adiponectin in Relation to Infant Body Composition up to 2 Years. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhshi, A.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Rooki, H.; Vakili, R.; Hashemy, S.I.; Mirhafez, S.R.; Shakeri, M.T.; Kashanifar, R.; Pourbafarani, R.; Mirzaei, H.; et al. Comparative Measurement of Ghrelin, Leptin, Adiponectin, EGF and IGF-1 in Breast Milk of Mothers with Overweight/Obese and Normal-Weight Infants. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D.A.; Schneider, C.R.; Pavela, G. A Narrative Review of the Associations between Six Bioactive Components in breastmilk and Infant Adiposity. Obesity 2016, 24, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan Castell, M.F.; Peraita-Costa, I.; Soriano, J.M.; Llopis-Morales, A.; Morales-Suarez-Varela, M. A Review of the Relationship Between the Appetite-Regulating Hormone Leptin Present in Human Milk and Infant Growth. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundar, N.O.; Anal, O.; Dundar, B.; Ozkan, H.; Caliskan, S.; Büyükgebiz, A. Longitudinal Investigation of the Relationship between Breast Milk Leptin Levels and Growth in Breast-Fed Infants. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 18, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, C.; Oliver, P.; Sánchez, J.; Miralles, O.; Caimari, A.; Priego, T.; Palou, A. The Intake of Physiological Doses of Leptin during Lactation in Rats Prevents Obesity in Later Life. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağiran Yilmaz, F.; Özçelik, A.Ö. The Relationships between Leptin Levels in Maternal Serum and Breast Milk of Mothers and Term Infants. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doneray, H.; Orbak, Z.; Yildiz, L. The Relationship between Breast Milk Leptin and Neonatal Weight Gain. Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockway, M.M.; Daniel, A.I.; Reyes, S.M.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Granger, M.; McDermid, J.M.; Chan, D.; Refvik, R.; Sidhu, K.K.; Musse, S.; et al. Human Milk Bioactive Components and Child Growth and Body Composition in the First 2 Years: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulou, M.; Panigrahi, S.K.; Jaconia, G.D.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C.; Smiley, R.M.; Page-Wilson, G. Pregnancy-Specific Adaptations in Leptin and Melanocortin Neuropeptides in Early Human Gestation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e5156–e5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson-Hall, U.; de Maré, H.; Askeli, F.; Börjesson, M.; Holmäng, A. Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Association with Changes in Fat Mass and Adipokines in Women of Normal-Weight or with Obesity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becic, T.; Studenik, C.; Hoffmann, G. Exercise Increases Adiponectin and Reduces Leptin Levels in Prediabetic and Diabetic Individuals: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <25 | 8 (4.3) |

| 25–35 | 118 (63.4) | |

| >36 | 60 (32.3) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.5–24.9 | 55 (50.5) |

| 25–29.9 | 41 (37.6) | |

| >30 | 13 (11.9) | |

| Physical activity | Sedentary | 11 (7.5) |

| Low activity | 66 (44.9) | |

| Moderate activity | 55 (37.4) | |

| Quite active | 15 (10.2) | |

| Delivery type | Term | 109 (58.6) |

| Preterm | 77 (41.4) | |

| Number of deliveries | 1 | 101 (54.6) |

| 2 | 52 (28.1) | |

| ≥3 | 32 (17.3) | |

| Lactation stage | Colostrum | 36 (13.7) |

| 1 month | 107 (40.9) | |

| 2 months | 23 (8.8) | |

| 3 months | 33 (12.6) | |

| 4 months | 21 (8.0) | |

| 5 months | 10 (3.8) | |

| 6 months | 32 (12.2) |

| Spearman’s ρ | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn weight | −0.582 | 8.05 × 10−17 |

| Newborn length | −0.576 | 1.59 × 10−15 |

| Head circumference | −0.562 | 3.51 × 10−14 |

| Predictor | β | SE | 95% CI | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interceptor | 1.291 | 0.360 | 0.585 to 1.997 | 3.59 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.031 | 0.009 | 0.013 to 0.049 | 3.40 | 0.001 |

| Physical activity | |||||

| Low activity | −1.862 | 0.247 | −2.346 to −1.378 | −7.53 | <0.001 |

| Moderate activity | −1.952 | 0.250 | −2.442 to −1.462 | −7.80 | <0.001 |

| Quite active | −1.820 | 0.267 | −2.343 to −1.297 | −6.83 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (ref: Term group) | |||||

| Preterm group | 0.524 | 0.100 | 0.328 to 0.720 | 5.23 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Garro-Aguilar, Y.; Astigarraga, E.; Barreda-Gómez, G.; Martinez, O.; Simón, E. Maternal Determinants of Human Milk Leptin and Their Associations with Neonatal Growth Parameters. Nutrients 2026, 18, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020192

Garro-Aguilar Y, Astigarraga E, Barreda-Gómez G, Martinez O, Simón E. Maternal Determinants of Human Milk Leptin and Their Associations with Neonatal Growth Parameters. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020192

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarro-Aguilar, Yaiza, Egoitz Astigarraga, Gabriel Barreda-Gómez, Olaia Martinez, and Edurne Simón. 2026. "Maternal Determinants of Human Milk Leptin and Their Associations with Neonatal Growth Parameters" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020192

APA StyleGarro-Aguilar, Y., Astigarraga, E., Barreda-Gómez, G., Martinez, O., & Simón, E. (2026). Maternal Determinants of Human Milk Leptin and Their Associations with Neonatal Growth Parameters. Nutrients, 18(2), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020192