Influence of Certain Natural Bioactive Compounds on Glycemic Control: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Unripe Avocado Extract—Mannoheptulose

3.1. General Characterization

3.2. The Effect on Glucose and Insulin Levels

3.2.1. In Vitro Studies

3.2.2. Animal Studies

3.2.3. Human Studies

3.3. The Comparison with Antidiabetic Medications

3.4. Mechanism of Action

3.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

4. β-Carotene

4.1. General Characterization

4.2. The Effect on Glucose and Insulin Levels

4.2.1. In Vitro Studies

4.2.2. Animal Studies

4.2.3. Human Studies

4.3. The Comparison with Antidiabetic Medications

4.4. Mechanisms of Action

4.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

5. Resveratrol

5.1. General Characterization

5.2. The Effect on Glucose and Insulin Levels

5.2.1. In Vitro Studies

5.2.2. Animal Studies

5.2.3. Human Studies

5.3. The Comparison with Antidiabetic Medications

5.4. Mechanisms of Action

5.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

6. Steviosides

6.1. General Characterization

6.2. The Effect on Glucose and Insulin Levels

6.2.1. In Vitro Studies

6.2.2. Animal Studies

6.2.3. Human Studies

6.3. The Comparison with Antidiabetic Medications

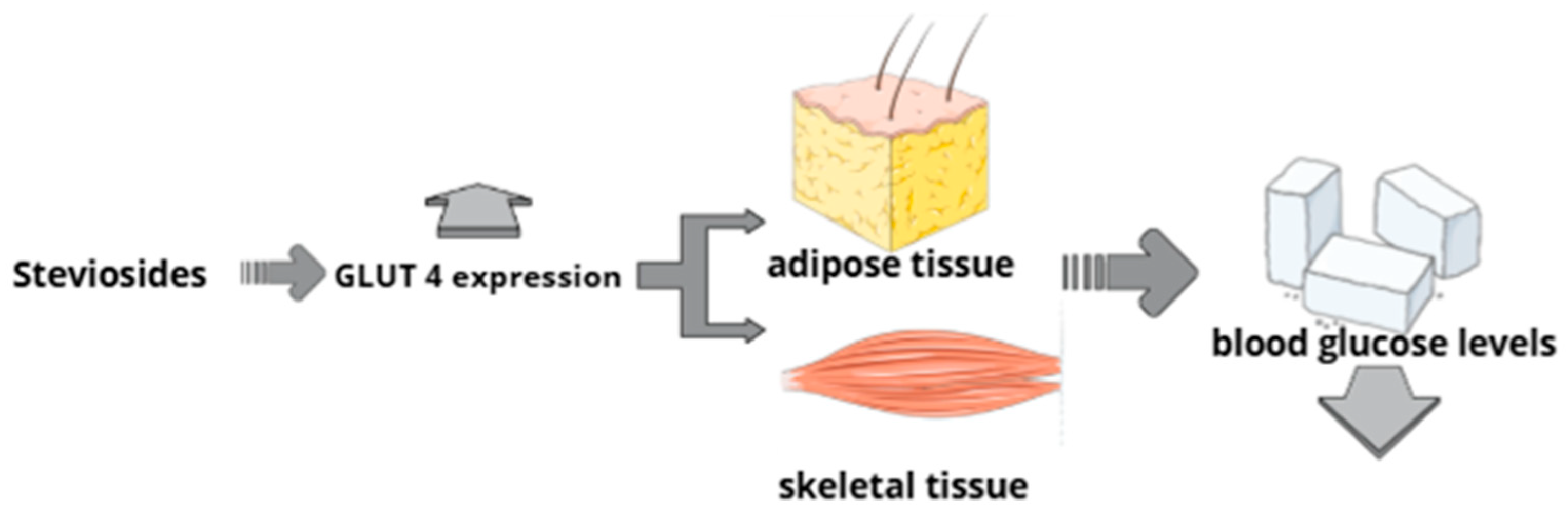

6.4. Mechanism of Action

6.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

7. Curcumin

7.1. General Characterization

7.2. The Effect on Glucose and Insulin Levels

7.2.1. In Vitro Studies

7.2.2. Animal Studies

7.2.3. Human Studies

7.3. The Comparison with Antidiabetic Medications

7.4. Mechanism of Action

7.5. Conclusions and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AEPAS | aqueous avocado seed extract |

| AEs | adverse events |

| AGE | advanced glycation end-products |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| AMP | adenosine monophosphate |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AMPKα1 | adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α1 subunit |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| AvX | avocado extract |

| Bax/Bcl-2 | Bcl-2-associated X protein/B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| Ca2+ | calcium ions |

| [Ca2+]i | intracellular calcium concentration |

| CAT | catalase |

| CD36 | cluster of differentiation 36 |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CREB | cAMP-response element-binding protein |

| CR | caloric restriction |

| CRM | caloric restriction mimetics |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| DASH | Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension |

| DCFDA | 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 |

| ERRα | Estrogen-related receptor alpha |

| FBG | fasting blood glucose |

| FGF15 | fibroblast growth factor 15 |

| FoxO1 | forkhead box O1 |

| FPG | fasting plasma glucose |

| FVJC | fruit and vegetable juice concentrate |

| G6Pase | glucose-6-phosphatase |

| Gac | carotenoid-rich Momordica cochinchinensis |

| GDM | gestational diabetes mellitus |

| GIR | glucose infusion rate |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLUT4 | glucose transporter type 4 |

| GSK-3β | glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| GSIS | glucose-stimulated insulin secretion |

| GTT | glucose tolerance test |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| HF | high-fat |

| HG | high glucose concentration |

| HK | hexokinase |

| HNF4α | Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 alpha |

| HOMA-B | Homeostatic Model Assessment for β-cell function |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance |

| HR | high concentration of resveratrol |

| hs-CRP | high-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| IKKβ | IκB kinase beta |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| IRS-1 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 |

| ITT | intention-to-treat |

| JC-1 | 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| K-ATP | ATP-sensitive potassium channel |

| KC | keratinocyte-derived chemokine |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LKB1 | liver kinase B1 |

| LR | low concentration of resveratrol |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MD | mean difference |

| MIP-1α | macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha |

| mRNA | messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| NRBC | naringenin and 2 µM β-carotene |

| Nrf-2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| OGTT | oral glucose tolerance test |

| PCOS | polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PEPCK | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PLC | receptor–phospholipase C |

| P53-AMC | p53-7-amino-4-methylcoumari |

| PON-1 | paraoxonase 1 |

| PPARα | proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PTT | pyruvate tolerance test |

| QUICKI | Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RQ | respiratory quotient |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RR | relative risk |

| RXR | retinoid X receptors |

| SCFA | short-chain fatty acid |

| SGLT1 | sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter |

| SHBG | sex hormone-binding globulin |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SR-B1 | scavenger receptor class B type 1 |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TUNEL | terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling |

| UCP1 | uncoupling protein 1 |

| WMD | weighted mean difference |

References

- Dutta, A.; Hossain, M.A.; Somadder, P.D.; Moli, M.A.; Ahmed, K.; Rahman, M.M.; Bui, F.M. Exploring the Therapeutic Targets of Stevioside in Management of Type 2 Diabetes by Network Pharmacology and in-Silico Approach. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí Del Moral, A.; Calvo, C.; Martínez, A. Ultra-processed food consumption and obesity-a systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.K.; Roth, G.S. Calorie Restriction Mimetics: Can You Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too? Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 20, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfahel, R.; Sawicki, T.; Jabłońska, M.; Przybyłowicz, K.E. Anti-Hyperglycemic Effects of Bioactive Compounds in the Context of the Prevention of Diet-Related Diseases. Foods 2023, 12, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobârcă, D.; Cătoi, A.F.; Gavrilaș, L.; Banc, R.; Miere, D.; Filip, L. Natural Bioactive Compounds in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic (Dysfunction)—Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uti, D.E.; Atangwho, I.J.; Alum, E.U.; Egba, S.I.; Ugwu, O.P.-C.; Ikechukwu, G.C. Natural Antidiabetic Agents: Current Evidence and Development Pathways from Medicinal Plants to Clinical use. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Khan, J.T.; Chowdhury, S.; Reberio, A.D.; Kumar, S.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A.; Flatt, P.R. Plant-Based Diets and Phytochemicals in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus and Prevention of Its Complications: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, D.K.; Roth, G.S. Glycolytic Inhibition: An Effective Strategy for Developing Calorie Restriction Mimetics. GeroScience 2020, 43, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.K.; Pistell, P.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yu, Y.; Massimino, S.; Davenport, G.M.; Hayek, M.; Roth, G.S. Characterization and Mechanisms of Action of Avocado Extract Enriched in Mannoheptulose as a Candidate Calorie Restriction Mimetic. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7367–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Manda, K.; Haridas, S.; Bhatt, A.N.; Saluja, D.; Dwarakanath, B.S. Chronic Dietary Administration of 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Does Not Compromise Neurobehavioral Functions at Tumor Preventive Doses in Mice. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2015, 5, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Hayek, M.; Massimino, S.; Davenport, G.; Arking, R.; Bartke, A.; Bonkowski, M.; Ingram, D. Mannoheptulose: Glycolytic Inhibitor and Novel Caloric Restriction Mimetic. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 553.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ingram, D.K.; Gumpricht, E.; De Paoli, T.; Teong, X.T.; Liu, B.; Mori, T.A.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Roth, G.S. Effects of an Unripe Avocado Extract on Glycaemic Control in Individuals with Obesity: A Double-Blinded, Parallel, Randomised Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, R.K.; Smith, D.L.; Sossong, A.M.; Kaushik, S.; Poosala, S.; Spangler, E.L.; Roth, G.S.; Lane, M.; Allison, D.B.; de Cabo, R.; et al. Chronic Ingestion of 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Induces Cardiac Vacuolization and Increases Mortality in Rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 243, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, E.P. Mannoheptulose and Insulin Inhibition. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1968, 150, 455–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.F.; Wolff, F.W. Trial of Mannoheptulose in Man. Metabolism 1970, 19, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktora, J.K.; Johnson, B.F.; Penhos, J.C.; Rosenberg, C.A.; Wolff, F.W. Effect of Ingested Mannoheptulose in Animals and Man. Metabolism 1969, 18, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, I.Y.; Khattab, A.R.; Selim, N.M.; Sobeh, M.; Elhawary, S.S.; Bishbishy, M.H.E. Metabolomics-Based Profiling of 4 Avocado Varieties Using HPLC–MS/MS and GC/MS and Evaluation of Their Antidiabetic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, U.S.M. Phytochemical Screening and In Vitro Antioxidant and Anti-Diabetic Potentials of Persea Americana Mill. (Lauraceae) Fruit Extract. Univers. J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehikioya, C.O.; Osagie, A.M.; Omage, S.O.; Omage, K.; Azeke, M.A. Carbohydrate Digestive Enzyme Inhibition, Hepatoprotective, Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Benefits of Persea Americana. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, L.L.; Flickinger, E.A.; France, J.; Davenport, G.M.; Shoveller, A.K. Mannoheptulose has differential effects on fasting and postprandial energy expenditure and respiratory quotient in adult Beagle dogs fed diets of different macronutrient contents. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, M.A.; Davenport, G.M.; Atkinson, J.L.; Duncan, I.J.H.; Shoveller, A. Dietary Avocado-Derived Mannoheptulose Results in Increased Energy Expenditure After a 28 Day Feeding Trial in Cats. ResearchGate 2024, 12, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.A.; Edwards, C.G.; Thompson, S.V.; Hannon, B.A.; Burke, S.K.; Walk, A.D.M.; Mackenzie, R.W.A.; Reeser, G.E.; Fiese, B.H.; Burd, N.A.; et al. Avocado Consumption, Abdominal Adiposity, and Oral Glucose Tolerance Among Persons with Overweight and Obesity. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2513–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A.C.; Senn, M.K.; Rotter, J.I. Associations between Avocado Intake and Lower Rates of Incident Type 2 Diabetes in US Adults with Hispanic/Latino Ancestry. J. Diabetes Mellit. 2023, 13, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, D.; Guzman, G.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Avocado Consumption for 12 Weeks and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Overweight or Obesity and Insulin Resistance. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 1851–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamednia, S.; Shouhani, Z.; Tavakol, S.; Montazeri, N.; Amirkhan-Dehkordi, M.; Karimi, M.A.; Bastamkhani, M.; Tabrizy, H.C.; Amirsasan, R.; Vakili, J.; et al. Effects of Avocado Products on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adults: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeloro, B.M.; Barbalho, S.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; Raimundo, R.D.; Stevanato, B.L.; Assumpção, M.C.B.; Casangel, E.M.D.; Ito, E.H.; Barros, M.C.; Porto, A.A.; et al. Is Avocado Beneficial for Lipid Profiles? An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 69, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouamé, N.M.; Koffi, C.; N’Zoué, K.S.; Yao, N.A.R.; Doukouré, B.; Kamagaté, M. Comparative Antidiabetic Activity of Aqueous, Ethanol, and Methanol Leaf Extracts of Persea Americana and Their Effectiveness in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2019, 2019, 5984570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.A.; Amanze, J.C.; Oni, A.I.; Grant, S.; Iyobhebhe, M.; Elebiyo, T.C.; Rotimi, D.; Asogwa, N.T.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Ajiboye, B.O.; et al. Antidiabetic Activity of Avocado Seeds (Persea Americana Mill.) in Diabetic Rats via Activation of PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasaputra, D.; Wargasetia, T.; Elizabeth, E. Effects of Metformin, Avocado Seed, and Diabetic Ingredients Infusion to Weight and Fasting Blood Glucose on Sucrose Diet Rats. Glob. Med. Health Commun. GMHC 2019, 7, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Corbin, K.L.; Bogart, A.M.; Whitticar, N.B.; Waters, C.D.; Schildmeyer, C.; Vann, N.W.; West, H.L.; Law, N.C.; Wiseman, J.S.; et al. Reducing Glucokinase Activity Restores Endogenous Pulsatility and Enhances Insulin Secretion in Islets from Db/Db Mice. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3747–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, G.; Kraicer, P.F. Metabolic Effects of Insulin Blockade by D-Mannoheptulose in the Sand Rat (Psammomys Obesus) and the Rat. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1972, 19, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, Y.; Fatima, S.N.; Shahid, S.M.; Mahboob, T. Nephroprotective Effects of B-Carotene on ACE Gene Expression, Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Status in Thioacetamide Induced Renal Toxicity in Rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 29, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Eggersdorfer, M.; Wyss, A. Carotenoids in Human Nutrition and Health. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 652, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, N.E.; Focsan, A.L.; Gao, Y.; Kispert, L.D. The Endless World of Carotenoids—Structural, Chemical and Biological Aspects of Some Rare Carotenoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronel, J.; Pinos, I.; Amengual, J. β-Carotene in Obesity Research: Technical Considerations and Current Status of the Field. Nutrients 2019, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, G.; Machate, D.J.; Freitas, K.D.C.; Hiane, P.A.; Maldonade, I.R.; Pott, A.; Asato, M.A.; Candido, C.J.; Guimarães, R.d.C.A. β-Carotene: Preventive Role for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampousi, A.-M.; Lundberg, T.; Löfvenborg, J.E.; Carlsson, S. Vitamins C, E, and β-Carotene and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimbalkar, V.; Joshi, U.; Shinde, S.; Pawar, G. In-Vivo and in-Vitro Evaluation of Therapeutic Potential of β- Carotene in Diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021, 20, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.A.; Greenway, F.L.; Zhang, D.; Ghosh, S.; Coulter, C.R.; James, S.L.; He, Y.; Cusimano, L.A.; Rebello, C.J. Naringenin and β-Carotene Convert Human White Adipocytes to a Beige Phenotype and Elevate Hormone- Stimulated Lipolysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1148954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, N.; Gao, Z. β-Carotene Regulates Glucose Transport and Insulin Resistance in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus by Increasing the Expression of SHBG. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szybiak-Skora, W.; Cyna, W.; Lacka, K. New Insights in the Diagnostic Potential of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG)—Clinical Approach. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojnić, B.; Serrano, A.; Sušak, L.; Palou, A.; Bonet, M.L.; Ribot, J. Protective Effects of Individual and Combined Low Dose Beta-Carotene and Metformin Treatments against High-Fat Diet-Induced Responses in Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateel, R.; Kashyap, N.N.; Reddy, S.K.; Shetty, S.; Kumari, M.K.; Ullal, S.D.; Holla, S.N.; Aroor, A.; Hill, M.A.; Belle, V.S.; et al. Chronic β-Carotene, Magnesium, and Zinc Supplementation Together with Metformin Attenuates Diabetes-Related Complications in Aged Rats. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 50, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-Y.; Hou, W.-C.; Hsu, S.-J.; Liaw, C.-C.; Huang, C.; Shih, M.-C.M.; Shen, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-F.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, O.K.; et al. Consumption of Carotenoid-Rich Momordica Cochinchinensis (Gac) Aril Improves Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetic Mice Partially through Taste Receptor Type 1 Mediated Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Secretion. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 11415–11431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canas, J.A.; Damaso, L.; Altomare, A.; Killen, K.; Hossain, J.; Balagopal, P.B. Insulin Resistance and Adiposity in Relation to Serum β-Carotene Levels. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 58–64.e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemi, Z.; Alizadeh, S.-A.; Ahmad, K.; Goli, M.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Effects of Beta-Carotene Fortified Synbiotic Food on Metabolic Control of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Double-Blind Randomized Cross-over Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.W.; Sun, Z.H.; Tong, W.W.; Yang, K.; Guo, K.Q.; Liu, G.; Pan, A. Dietary Intake and Circulating Concentrations of Carotenoids and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Observational Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, K.; Rajia, S.; Yeasmin, M.; Morshed, M.; Haque, R. Synergistic Effect of β-Carotene and Metformin on Antihyperglycemic and Antidyslipidemic Activities in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.M.; Ameer, M.A.; Goyal, A. Vitamin A Toxicity. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Kapur, A.; Gibson, B.; Bubb, K.; Alrawashdeh, M.; Cipkala-Gaffin, J. Preoperative Delirium Nursing Model Initiatives to Determine the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium Among Elderly Orthopaedic Patients. Orthop. Nurs. 2021, 40, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niekerk, A.; Wrzesinski, K.; Steyn, D.; Gouws, C. A Novel NCI-H69AR Drug-Resistant Small-Cell Lung Cancer Mini-Tumor Model for Anti-Cancer Treatment Screening. Cells 2023, 12, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Bautista, S.A.; Mehta, S.; Briceño, C.A. Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis with Bilateral Orbital Vein Involvement and Diffuse Ischemic Retinopathy. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2023, 86, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabandehloo, H.; Seyyedebrahimi, S.; Esfahani, E.N.; Razi, F.; Meshkani, R. Resveratrol Supplementation Decreases Blood Glucose without Changing the Circulating CD14 + CD16 + Monocytes and Inflammatory Cytokines in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutr. Res. 2018, 54, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Resveratrol: An Overview of Its Anti-Cancer Mechanisms. Life Sci. 2018, 207, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeczka, A.; Kordowitzki, P. Resveratrol and SIRT1: Antiaging Cornerstones for Oocytes? Nutrients 2022, 14, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Resveratrol Therapy on Glucose Metabolism, Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Renal Function in the Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Protocol. Medicine 2022, 101, e30049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshivhase, A.M.; Matsha, T.; Raghubeer, S. Resveratrol Attenuates High Glucose-Induced Inflammation and Improves Glucose Metabolism in HepG2 Cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Scott, E.; Brown, V.A.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P.; Brown, K. Clinical Trials of Resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianetto, S.; Ménard, C.; Quirion, R. Neuroprotective Action of Resveratrol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoliga, J.M.; Baur, J.A.; Hausenblas, H.A. Resveratrol and Health—A Comprehensive Review of Human Clinical Trials. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1129–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowski, L.D.; Yoshimoto, M.; da Silva Bellucco, F.T.; Belangero, S.I.N.; Christofolini, D.M.; Pacanaro, A.N.X.; Bortolai, A.; de Smith, M.A.C.; Squire, J.A.; Melaragno, M.I. Cytogenetic Molecular Delineation of a Terminal 18q Deletion Suggesting Neo-Telomere Formation. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 53, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radeva, L.; Yoncheva, K. Resveratrol—A Promising Therapeutic Agent with Problematic Properties. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoliga, J.M.; Blanchard, O. Enhancing the Delivery of Resveratrol in Humans: If Low Bioavailability Is the Problem, What Is the Solution? Molecules 2014, 19, 17154–17172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajima, R.; Sakakibara, Y.; Sakurai-Yamatani, N.; Muraoka, M.; Saga, Y. Formal Proof of the Requirement of MESP1 and MESP2 in Mesoderm Specification and Their Transcriptional Control via Specific Enhancers in Mice. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2021, 148, dev194613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jevtovic, F.; Krassovskaia, P.M.; Chaves, A.B.; Zheng, D.; Treebak, J.T.; Houmard, J.A. Effect of Resveratrol on Insulin Action in Primary Myotubes from Lean Individuals and Individuals with Severe Obesity. Am. J. Physiol.—Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E398–E406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Mitochondrial Function and Protects against Metabolic Disease by Activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Ren, B.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, F. The Effect of Resveratrol on Blood Glucose and Blood Lipids in Rats with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2021, 2021, 2956795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, M.M.; Vestergaard, P.F.; Clasen, B.F.; Radko, Y.; Christensen, L.P.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Møller, N.; Jessen, N.; Pedersen, S.B.; Jørgensen, J.O.L. High-Dose Resveratrol Supplementation in Obese Men. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, B.I.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Influence of Age and Dose on the Effect of Resveratrol for Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Molecules 2022, 27, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhaleem, I.A.; Brakat, A.M.; Adayel, H.M.; Asla, M.M.; Rizk, M.A.; Aboalfetoh, A.Y. The Effects of Resveratrol on Glycemic Control and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Patients with T2DM: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Clin. 2022, 158, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frendo-Cumbo, S.; MacPherson, R.E.K.; Wright, D.C. Beneficial Effects of Combined Resveratrol and Metformin Therapy in Treating Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Vázquez, M.; Antonieta, G. Effects of Combined Resveratrol Plus Metformin Therapy in Db/Db Diabetic Mice. J. Metab. Syndr. 2016, 5, 1001.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, B.I.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Hypoglycemic Effect of Resveratrol: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaito, A.; Posadino, A.M.; Younes, N.; Hasan, H.; Halabi, S.; Alhababi, D.; Al-Mohannadi, A.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Eid, A.H.; Nasrallah, G.K.; et al. Potential Adverse Effects of Resveratrol: A Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Ha, J. AMPK Activators: Mechanisms of Action and Physiological Activities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.L.; Gomes, A.P.; Ling, A.J.Y.; Duarte, F.V.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; North, B.J.; Agarwal, B.; Ye, L.; Ramadori, G.; Teodoro, J.S.; et al. SIRT1 Is Required for AMPK Activation and the Beneficial Effects of Resveratrol on Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ding, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Xia, Q.; Yin, K.; Song, S.; Wang, Z.; et al. Natural Products Targeting AMPK Signaling Pathway Therapy, Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1534634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A.M.; Huber, F.M.; Hoelz, A. Structural and Functional Analysis of Human SIRT1. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhan, L.; Wang, M.; Shi, R.; Yuan, X.; Gao, X.; Liu, X.; Zang, J.; Liu, W.; et al. Resveratrol-Induced Sirt1 Phosphorylation by LKB1 Mediates Mitochondrial Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Hao, J. Resveratrol Mitigates Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction via SIRT1/PPAR-α/PGC-1 Pathway. Mol. Genet. Genomics MGG 2025, 300, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasbullah, A.M.; Binesh, A.; Venkatachalam, K. Resveratrol as a Regulator of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Glucose Stability in Diabetes. Anti-Inflamm. Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, T.; Zhu, T.; Hu, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, C.; et al. Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni as a Sweet Herbal Medicine: Traditional Uses, Potential Applications, and Future Development. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1638147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteliuk, V.; Rybchuk, L.; Bayliak, M.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, O. Natural Sweetener Stevia Rebaudiana: Functionalities, Health Benefits and Potential Risks. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1412–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohinejad, S.; Koubaa, M.; Gharibzahedi, S.M.T. Drying Technologies for Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni: Advances, Challenges, and Impacts on Bioactivity for Food Applications—A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1131/2011 of 11 November 2011 Amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Steviol Glycosides Text with EEA Relevance. 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/1131/oj/eng (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Grinberga, J.; Beitane, I. A Review: Alternatives to Substitute Fructose in Food Products for Patients with Diabetes. In Research for Rural Development; Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies: Jelgava, Latvia, 2023; Volume 38, pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch-Siemińska, M.; Wawerska, K.; Gawroński, J. The Potential of Plant Tissue Cultures to Improve the Steviol Glycoside Profile of Stevia (Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni) Regenerants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashad, N.M.; Abdelsamad, M.A.E.; Amer, A.M.; Sitohy, M.Z.; Mousa, M.M. The Impact of Stevioside Supplementation on Glycemic Control and Lipid Profile in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 31, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xue, L.; Guo, C.; Han, B.; Pan, C.; Zhao, S.; Song, H.; Ma, Q. Stevioside Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance and Adipose Tissue Inflammation by Downregulating the NF-κB Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 417, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Navale, A. The Natural Sweetener Stevia: An Updated Review on Its Phytochemistry, Health Benefits, and Anti-Diabetic Study. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2024, 20, e010523216398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana-Paucar, A.M. Steviol Glycosides from Stevia Rebaudiana: An Updated Overview of Their Sweetening Activity, Pharmacological Properties, and Safety Aspects. Molecules 2023, 28, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, L.; Mustapha, A.T.; Yu, X.; Zhou, C.; Okonkwo, C.E. Natural and Low-Caloric Rebaudioside A as a Substitute for Dietary Sugars: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 615–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, P.B.; Gregersen, S.; Poulsen, C.R.; Hermansen, K. Stevioside Acts Directly on Pancreatic 13 Cells to Secrete Insulin: Actions Independent of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate and Adenosine Triphosphate-Sensitive K+—Channel Activity. Metabolism 2000, 49, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toskulkao, C.; Sutheerawattananon, M.; Piyachaturawat, P. Inhibitory Effect of Steviol, a Metabolite of Stevioside, on Glucose Absorption in Everted Hamster Intestine in Vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 1995, 80, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Qi, H.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. Transmembrane Transport of Steviol Glucuronide and Its Potential Interaction with Selected Drugs and Natural Compounds. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 86, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasker, S.; Madhav, H.; Chinnamma, M. Molecular Evidence of Insulinomimetic Property Exhibited by Steviol and Stevioside in Diabetes Induced L6 and 3T3L1 Cells. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, C.; Zambonin, L.; Rizzo, B.; Maraldi, T.; Angeloni, C.; Vieceli Dalla Sega, F.; Fiorentini, D.; Hrelia, S. Glycosides from Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni Possess Insulin-Mimetic and Antioxidant Activities in Rat Cardiac Fibroblasts. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 3724545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruiz, J.C.; Moguel-Ordoñez, Y.B.; Matus-Basto, A.J.; Segura-Campos, M.R. Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Activity of Stevia Rebaudiana Extracts (Var. Morita) and Their Incorporation into a Potential Functional Bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 7894–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, J.M.; Król, E.; Krejpcio, Z. Steviol Glycosides Supplementation Affects Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Fed STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. Nutrients 2021, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, N.; Naika, M.; Khanum, F.; Kaul, V.K. Antioxidant, Anti-Diabetic and Renal Protective Properties of Stevia rebaudiana. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2013, 27, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritu, M.; Nandini, J. Nutritional Composition of Stevia Rebaudiana, a Sweet Herb, and Its Hypoglycaemic and Hypolipidaemic Effect on Patients with Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4231–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, C.C.B.; Rafiq, S.; Jeppesen, P.B. Effect of Steviol Glycosides on Human Health with Emphasis on Type 2 Diabetic Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare, M.; Zeinalabedini, M.; Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S.; Bellissimo, N.; Azadbakht, L. Effect of Stevia on Blood Glucose and HbA1C: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2024, 18, 103092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deenadayalan, A.; Subramanian, V.; Paramasivan, V.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Rengasamy, G.; Sadagopan, J.C.; Rajagopal, P.; Jayaraman, S. Stevioside Attenuates Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle by Facilitating IR/IRS-1/Akt/GLUT 4 Signaling Pathways: An In Vivo and In Silico Approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aal, R.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.S.; Ali, L. Stevia Improves the Antihyperglycemic Effect of Metformin in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats: A Novel Strategy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Bull. Pharm. Sci. Assiut Univ. 2019, 42, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumon, M.M.H.; Mostofa, M.; Jahan, M.; Kayesh, M.E.H.; Haque, M. Comparative Efficacy of Powdered Form of Stevia (Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni) Leaves and Glimepiride in Induced Diabetic Rats. Bangladesh J. Vet. Med. 2009, 6, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-Y.; Park, M.; Lee, H.-J. Stevia (Stevia Rebaudiana) Extract Ameliorates Insulin Resistance by Regulating Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress in the Skeletal Muscle of Db/Db Mice. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasti, A.N.; Nikolaki, M.D.; Synodinou, K.D.; Katsas, K.N.; Petsis, K.; Lambrinou, S.; Pyrousis, I.A.; Triantafyllou, K. The Effects of Stevia Consumption on Gut Bacteria: Friend or Foe? Microorganisms 2022, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, R.; Shinozaki, Y.; Ohta, T. Sodium–Glucose Cotransporters: Functional Properties and Pharmaceutical Potential. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, B.; Peng, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhan, S.; Yang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, W. Research on the Effects of Different Sugar Substitutes-Mogroside V, Stevioside, Sucralose, and Erythritol-On Glucose, Lipid, and Protein Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Food Res. Int. Ott. Ont 2025, 209, 116262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwell, M. Stevia, Nature’s Zero-Calorie Sustainable Sweetener: A New Player in the Fight Against Obesity. Nutr. Today 2015, 50, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Hu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Mei, S.; Zhu, G.; Yue, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S. Structure, Properties, and Biomedical Activity of Natural Sweeteners Steviosides: An Update. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, R.; Li, K.; Bai, X.; Qi, N.; Qu, H.; Li, G. Effects and Mechanisms of Steviol Glycosides on Glucose Metabolism: Evidence From Preclinical Studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelczyńska, M.; Moszak, M.; Wesołek, A.; Bogdański, P. The Preventive Mechanisms of Bioactive Food Compounds against Obesity-Induced Inflammation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: From Kitchen to Clinic. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Ghosh, S.; Negm, S.H.; Salem, H.M.; Fahmy, M.A.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Ibrahim, E.H.; et al. Curcumin, an Active Component of Turmeric: Biological Activities, Nutritional Aspects, Immunological, Bioavailability, and Human Health Benefits—A Comprehensive Review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1603018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, J.M.; Kim, E.-K.; Lee, J.O.; Lee, S.K.; Jung, J.H.; You, G.Y.; Park, S.H.; Suh, P.-G.; Kim, H.S. Curcumin Stimulates Glucose Uptake through AMPK-P38 MAPK Pathways in L6 Myotube Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 223, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, N.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, C. Curcumin Protects Islet Cells from Glucolipotoxicity by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and NADPH Oxidase Activity Both in Vitro and in Vivo. Islets 2019, 11, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Zhou, X.; Fujimoto, S.; Fukuda, K.; Toyoda, K.; Nishi, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Yamada, K.; Yamada, Y.; et al. Curcumin Inhibits Glucose Production in Isolated Mice Hepatocytes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2008, 80, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, X. Curcumin Protects Islet Beta Cells from Streptozotocin-induced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Injury via Its Antioxidative Effects. Endokrynol. Pol. 2022, 73, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, L.; Li, D. Curcumin Improves Insulin Sensitivity in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice through Gut Microbiota. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Nishikawa, S.; Ikehata, A.; Dochi, K.; Tani, T.; Takahashi, T.; Imaizumi, A.; Tsuda, T. Curcumin Improves Glucose Tolerance via Stimulation of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Secretion. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Nuo Feng, J.; Jin, T. 1654-P: Hepatic FGF21 Is Required for Curcumin and Resveratrol to Exert Their Metabolic Beneficial Effect in Male Mice. Diabetes 2023, 72, 1654-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.N.; Shao, W.; Yang, L.; Pang, J.; Ling, W.; Liu, D.; Wheeler, M.B.; He, H.H.; Jin, T. Hepatic Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Is Required for Curcumin or Resveratrol in Exerting Their Metabolic Beneficial Effect in Male Mice. Nutr. Diabetes 2025, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuengsamarn, S.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Luechapudiporn, R.; Phisalaphong, C.; Jirawatnotai, S. Curcumin Extract for Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghari, K.M.; Saleh, P.; Salekzamani, Y.; Dolatkhah, N.; Aghamohammadzadeh, N.; Hashemian, M. The Effect of Curcumin and High-Content Eicosapentaenoic Acid Supplementations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Double-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehzad, M.J.; Ghalandari, H.; Nouri, M.; Askarpour, M. Effects of Curcumin/Turmeric Supplementation on Glycemic Indices in Adults: A Grade-Assessed Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, Y.-J.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wu, M.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Horng, Y.-S.; Wu, H.-C. Effects of Curcumin on Glycemic Control and Lipid Profile in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Kim, Y. Is Curcumin Intake Really Effective for Chronic Inflammatory Metabolic Disease? A Review of Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, J.; Haedi, A.R.; Zhou, M. The Effect of Curcumin Supplementation on Glycemic Indices in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Meta-Analyses. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2024, 175, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, A.M.; Elbahy, D.A.; Ahmed, A.R.; Thabet, S.A.; Refaei, R.A.; Ragab, I.; Elmahdy, S.M.; Osman, A.S.; Abouelella, A.M. Comparison of the Efficacy of Curcumin and Its Nano Formulation on Dexamethasone-Induced Hepatic Steatosis, Dyslipidemia, and Hyperglycemia in Wistar Rats. Heliyon 2024, 10, e41043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxo, D.F.; Arcaro, C.A.; Gutierres, V.O.; Costa, M.C.; Oliveira, J.O.; Lima, T.F.O.; Assis, R.P.; Brunetti, I.L.; Baviera, A.M. Curcumin Combined with Metformin Decreases Glycemia and Dyslipidemia, and Increases Paraoxonase Activity in Diabetic Rats. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghhi, F.; Ghaznavi, H.; Sheervalilou, R.; Razavi, M.; Sepidarkish, M. Effects of Metformin and Curcumin in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Factorial Clinical Trial. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgalaboni, K.; Mashaba, R.G.; Phoswa, W.N.; Lebelo, S.L. Curcumin Attenuates Hyperglycemia and Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Quantitative Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; He, L.; Liu, L.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, F.; Cao, D.; He, Y. A Comprehensive Review on the Benefits and Problems of Curcumin with Respect to Human Health. Molecules 2022, 27, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiren, G.; Severcan, Ç.; Severcan, S.M.; Paşaoğlu, H. The Effect of Curcumin on PI3K/Akt and AMPK Pathways in Insulin Resistance Induced by Fructose. Turk. J. Biochem. 2024, 49, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servida, S.; Piontini, A.; Gori, F.; Tomaino, L.; Moroncini, G.; De Gennaro Colonna, V.; La Vecchia, C.; Vigna, L. Curcumin and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Overview with Focus on Glycemic Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; You, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Du, M.; Zou, T. Curcumin Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis and Obesity in Association with Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Mice. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takikawa, M.; Kurimoto, Y.; Tsuda, T. Curcumin Stimulates Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Secretion in GLUTag Cells via Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II Activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 435, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. Curcumin Anti-Diabetic Effect Mainly Correlates with Its Anti-Apoptotic Actions and PI3K/Akt Signal Pathway Regulation in the Liver. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyari, M.; Ghoflchi, S.; Hashemy, S.I.; Hashemi, S.F.; Reihani, A.; Hosseini, H. The PI3K/Akt Pathway: A Target for Curcumin’s Therapeutic Effects. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, R.; Mokhtari, Y.; Yousefi, A.; Bashash, D. The PI3K/Akt Signaling Axis and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM): From Mechanistic Insights into Possible Therapeutic Targets. Cell Biol. Int. 2024, 48, 1049–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, X.; Ma, J. Curcumin Inhibits High Glucose-induced Inflammatory Injury in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells through the ROS-PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 19, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliyari, M.; Hashemy, S.I.; Hashemi, S.F.; Reihani, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Hosseini, H.; Sahebkar, A. Targeting the Akt Signaling Pathway: Exploiting Curcumin’s Anticancer Potential. Pathol.—Res. Pract. 2024, 261, 155479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-K.; Lin, S.-R.; Chang, C.-H.; Tsai, M.-J.; Lee, D.-N.; Weng, C.-F. Natural Phenolic Compounds Potentiate Hypoglycemia via Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, N.; Kolibabka, M.; Busch, S.; Bugert, P.; Kaiser, U.; Lin, J.; Fleming, T.; Morcos, M.; Klein, T.; Schlotterer, A.; et al. The DPP4 Inhibitor Linagliptin Protects from Experimental Diabetic Retinopathy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.P.; Pratley, R.E. GLP-1 Analogs and DPP-4 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Therapy: Review of Head-to-Head Clinical Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, G.; Olawale, F.; Liu, J.; Lee, D.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Chaffin, N.; Alake, S.; Lucas, E.A.; Zhang, G.; Egan, J.M.; et al. Curcumin Mitigates Gut Dysbiosis and Enhances Gut Barrier Function to Alleviate Metabolic Dysfunction in Obese, Aged Mice. Biology 2024, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Yao, Y.; Gao, P.; Bu, S. The Therapeutic Efficacy of Curcumin vs. Metformin in Modulating the Gut Microbiota in NAFLD Rats: A Comparative Study. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 555293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MH Form | MH Dosage | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh avocado fruit | 2.15–12.83 g (33–200 mg/kg) | No significant changes | Significant decrease in insulin levels in 5 of 8 participants (p < 0.05) | [16] |

| MH solution (pilot + cross-over) | 5–20 g/day | Increase of ~15% (1.5–4 h), return to normal after approx. 6 h | No increase, although sometimes a weakened early insulin response | [15] |

| AvX | 10 g/day (~190 mg MH, ~2 mg/kg) | No significant changes in glucose AUC | Tendency to reduce insulin AUC, especially in participants with hyperinsulinemia | [12] |

| Model | Dosage/Exposure | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 insulin-resistant liver cells | 15 μM β-carotene | ↑ Glucose consumption (~1.49×), compared to metformin (0.1 μg/mL) (1.72×) | Insulin-like | [38] |

| L6 skeletal muscle cells | Not specified | ↑ Glucose uptake (~1.4×), comparable to insulin (1.47×); low cytotoxicity | Insulin-mimetic | |

| Human adipocytes (co-treatment) | β-carotene + naringenin | ↑ GLUT4, UCP1, adiponectin expression; ↑ PPARα, PPARγ, PGC-1α | ↑ Insulin sensitivity, ↑ thermogenesis | [39] |

| Gestational diabetes in vitro model | β-carotene | ↑ SHBG expression → ↑ GLUT4 → improved glucose transport | Improved insulin responsiveness | [40] |

| Model | Dosage/Treatment | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFD-induced obese mice | β-carotene 3 mg/kg/day | ↓ Hepatic fat, ↑ glucose utilization | ↑ Insulin sensitivity | [42] |

| HFD mice + metformin | β-carotene + metformin | Synergistic effect: ↑ glucose oxidation | ↑ Insulin signaling, ↑ metabolic gene expression | |

| Aged diabetic rats | β-carotene + Mg + Zn + metformin | Better glycemic control vs. metformin alone | ↑ Insulin sensitivity | [43] |

| T2D mice fed Gac fruit aril | High in β-carotene | ↓ FBG, ↑ glucose tolerance | ↑ GLP-1 (~2×), ↑ β-cell function | [44] |

| GLP-1 receptor KO mice + Gac aril | High in β-carotene | Glycemia reduction | Confirms GLP-1-mediated mechanism |

| Model | Dosage/Treatment | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 adults (30–70 y/o) with T2D, on hypoglycemics, BMI < 35 | 800 mg/day (2 × 400 mg), 8 weeks | Significant decrease in fasting glucose (−31.84 ± 47.6 mg/dL); no change in HbA1c | Not reported | [53] |

| 24 obese males (18–70 y/o), BMI > 30 | 1500 mg/day (3 × 500 mg), 4 weeks | No significant change in glucose or HbA1c | Not reported | [68] |

| 472 elderly patients (>60 y/o) with T2D | 500 mg/day, 6 months | HbA1c decreased > 2%; improved SIRT1 and AMPK expression; increased G6Pase activity | Improved insulin sensitivity (based on SIRT1/AMPK pathway) | [56] |

| Meta-analysis: 921 subjects (45–59 y/o and ≥60 y/o) | 250–500 mg/day as optimal dose | Significant improvement in glycemic control (↓ glucose, HbA1c) | Improved insulin sensitivity (↓ HOMA-IR), especially in ≥60 y.o. group | [69] |

| Meta-analysis: 871 T2D patients | ≥500 mg/day | Significant improvement in glycemic control (↓ glucose, HbA1c) | Not reported | [70] |

| Model | Dosage/ Treatment | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 adults | 1 g/day powdered stevia leaf, 60 days | Significant decrease in FBG (form 156.61 ± 31.32 to 123.55 ± 22.94 mg/dL) and postprandial glucose (from 225.17 ± 43.86 to 200.60 ± 43.80 mg/dL); no change in control group | Not reported | [101] |

| 150 participants: 40 with T2D, 60 obese, 50 healthy controls | 4 mg/kg b.w./day, 24 weeks | Improved glycemic control, ↓ HbA1c, ↓ LDL, ↓ triglycerides; weight gain in obese group | Decreased fasting serum insulin; improved insulin sensitivity | [88] |

| Meta-analyses of 7 RCTs, including 462 participants with hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia | Various doses (200–1500 mg/day) and durations across studies (4 h–2 years) | No statistically significant changes in FBG or HbA1c, though a downward trend was observed | No reported | [102] |

| Meta-analyses of 26 RCTs including 1439 individuals with T2D, IR, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or healthy subjects | Various doses (13.2–4000 mg/day) and durations across studies (1 day–2 years) | Significant reduction in FBG (WMD = −3.84; 95% CI: −7.15 to −0.53; p = 0.02), especially in individuals with high BMI or T2D | Some improvement in insulin sensitivity in subjects with T2D or high BMI | [103] |

| Model | Dosage/Treatment | Effect on Glucose | Effect on Insulin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 240 prediabetic subjects, 9-month double-blind RCT | Curcumin extract, 750 mg twice daily (9 months) | Prevented T2D development (0% vs. 16.4% in placebo, p < 0.001); improved glucose regulation across 3, 6, and 9 months | ↑ HOMA-β (61.58 vs. 48.72; p < 0.01); ↓ HOMA-IR (3.22 vs. 4.04; p < 0.001); ↑ adiponectin (22.46 vs. 18.45; p < 0.01) | [125] |

| 100 T2D patients; EPA + nano-curcumin co-administration | EPA (500 mg) + nano-curcumin (80 mg) daily, 12 weeks | Reduced hs-CRP; improved TAC; overall metabolic improvement | ↓ Insulin [MD: −1.44 (−2.70, −0.17)] | [126] |

| Meta-analysis of 59 RCTs | Curcumin/turmeric ≥ 500 mg/day; ≥12 weeks | ↓ Fasting glucose (WMD −4.60 mg/dL; 95% CI −5.55, −3.66); ↓ HbA1c (WMD −0.32%; 95% CI −0.45, −0.19) | ↓ Fasting insulin (WMD −0.87 µIU/mL; 95% CI –1.46, −0.27); ↓ HOMA-IR (WMD −0.33; 95% CI −0.43, −0.22) | [127] |

| Women with PCOS | 500–1500 mg/day, 6–12 weeks | ↓ Fasting glucose (MD: −2.77; 95% CI: −4.16, −1.38); improved lipid profile | ↓ Fasting insulin (MD: −1.33; 95% CI: −2.18, −0.49); ↓ HOMA-IR (MD: −0.32; 95% CI: −0.52, −0.12) | [128,129] |

| Umbrella review of 22 meta-analyses | Various curcumin doses | ↓ FBG and HbA1c | ↓ Insulin and HOMA-IR | [130] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pelczyńska, M.; Szymon, S.; Konieczny, M.; Bączyk, H.; Szyszko, J.; Cholewa, K.; Bogdański, P. Influence of Certain Natural Bioactive Compounds on Glycemic Control: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2026, 18, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010052

Pelczyńska M, Szymon S, Konieczny M, Bączyk H, Szyszko J, Cholewa K, Bogdański P. Influence of Certain Natural Bioactive Compounds on Glycemic Control: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010052

Chicago/Turabian StylePelczyńska, Marta, Starosta Szymon, Michał Konieczny, Hubert Bączyk, Jakub Szyszko, Krzysztof Cholewa, and Paweł Bogdański. 2026. "Influence of Certain Natural Bioactive Compounds on Glycemic Control: A Narrative Review" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010052

APA StylePelczyńska, M., Szymon, S., Konieczny, M., Bączyk, H., Szyszko, J., Cholewa, K., & Bogdański, P. (2026). Influence of Certain Natural Bioactive Compounds on Glycemic Control: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 18(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010052