Associations Between Dietary Intakes of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Blood Levels, and Pain Interference in People with Migraine: A Path Analysis of Randomized Trial Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

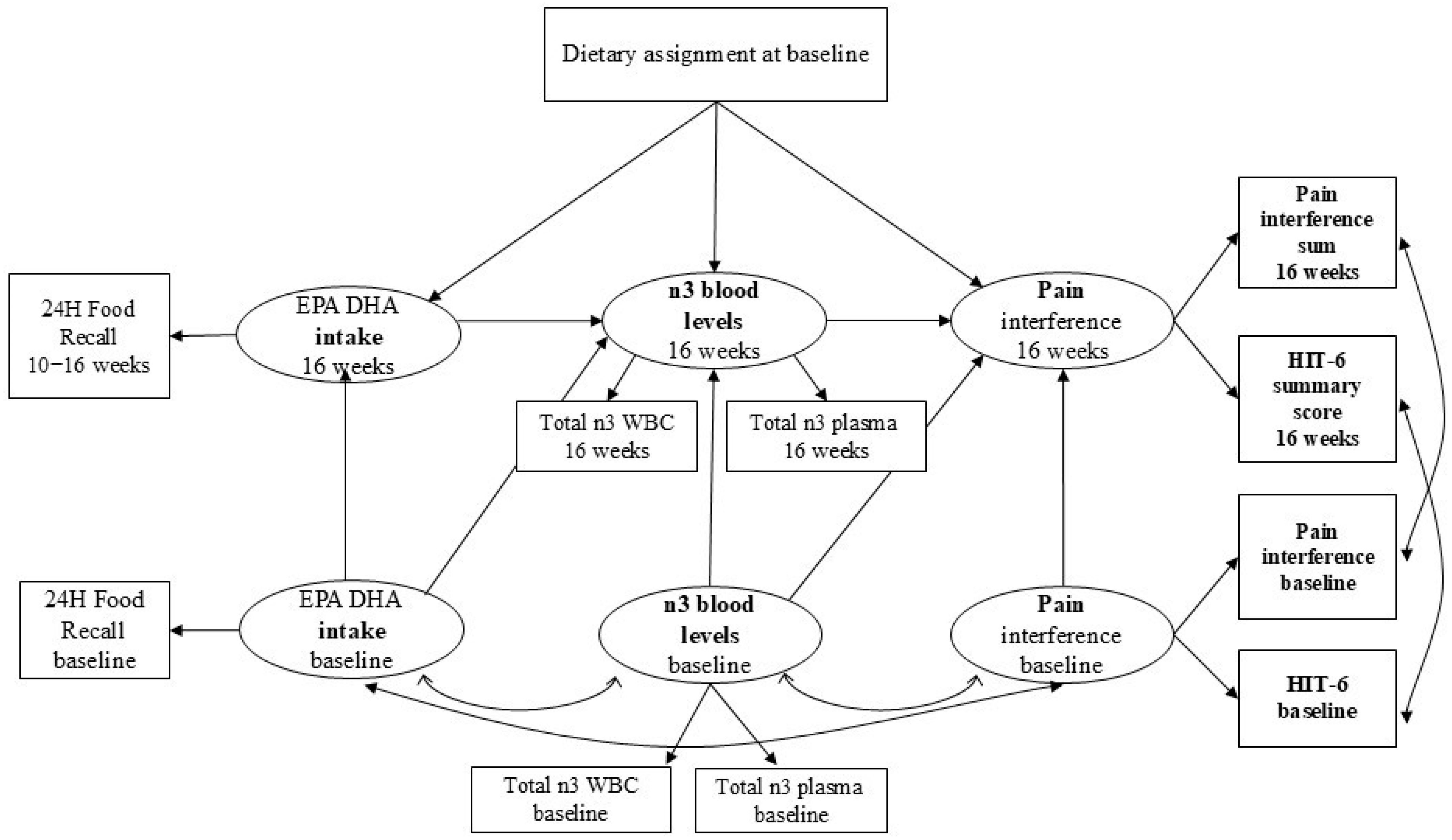

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Description of Sample

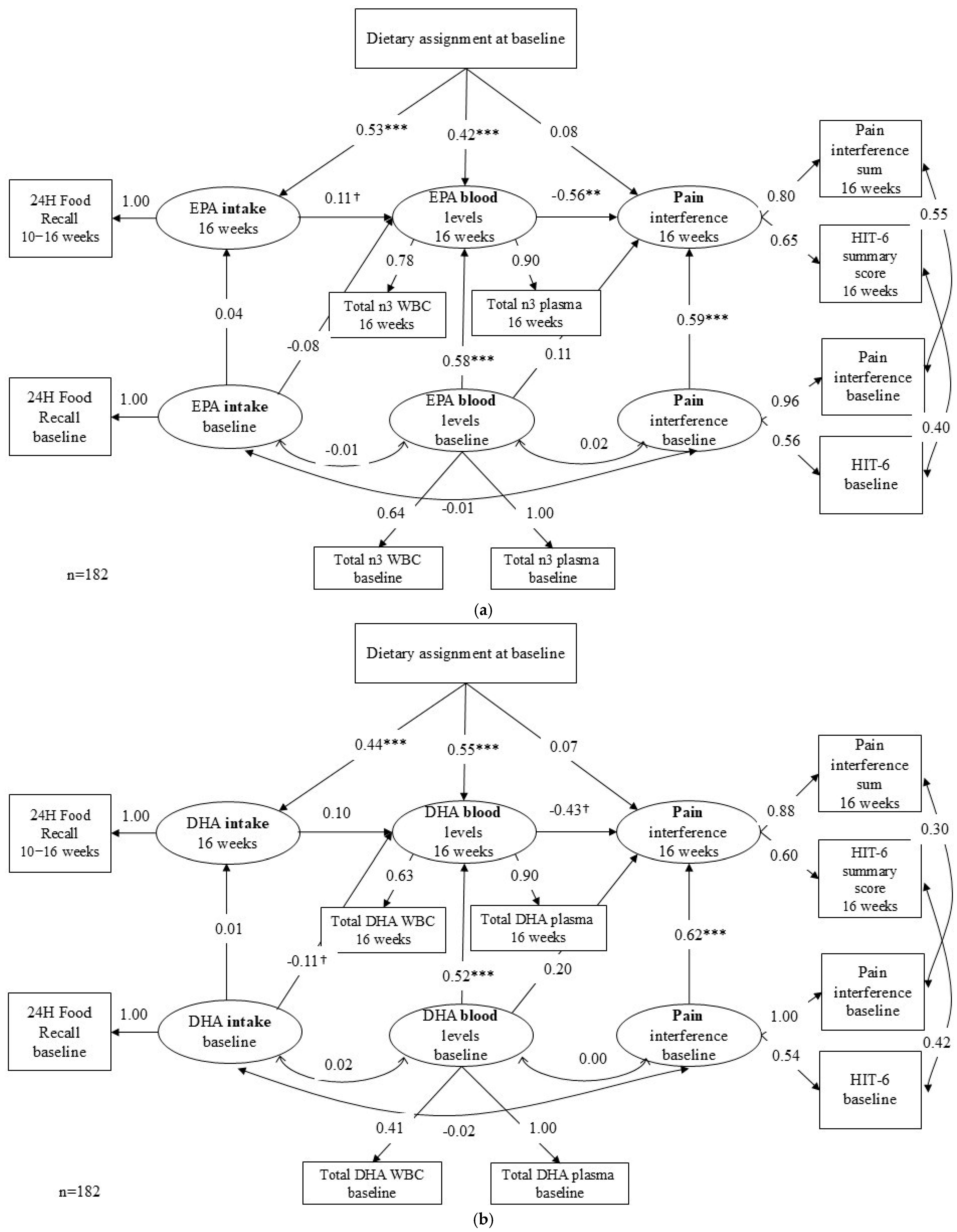

3.2. Model Results

3.2.1. Path 1 & 2: Diet Assignment to Food Intake to Blood n-3 Level

3.2.2. Path 3: Blood n-3 to Pain Interference

3.2.3. Indirect Effect and Direct Effect

3.2.4. Sensitivity Analysis Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Previous Studies

4.3. Study Limitations and Strengths

4.4. Next Steps and Gaps

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robbins, M.S. Diagnosis and management of headache: A review. JAMA 2021, 325, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailani, J.; Burch, R.C.; Robbins, M.S.; the Board of Directors of the American Headache Society. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2021, 61, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, D.C.; Yugrakh, M.S.; Lee, L.K.; Bell, J.; Cohen, J.M.; Lipton, R.B. Burden of Illness Among People with Migraine and ≥4 Monthly Headache Days While Using Acute and/or Preventive Prescription Medications for Migraine. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2020, 26, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houts, C.R.; Wirth, R.J.; McGinley, J.S.; Gwaltney, C.; Kassel, E.; Snapinn, S.; Cady, R. Content Validity of HIT-6 as a Measure of Headache Impact in People with Migraine: A Narrative Review. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2020, 60, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwedt, T.J.; Sahai-Srivastava, S.; Murinova, N.; Birlea, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Digre, K.; Lopez, K.; Mullally, W.; Blaya, M.T.; Pippitt, K.; et al. Determinants of pain interference and headache impact in patients who have chronic migraine with medication overuse: Results from the MOTS trial. Cephalalgia 2021, 41, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, L.; Anderson, D.R.; Blankson, M.L.; Channamsetty, V.; Blaz, J.W.; Nguyen-Louie, T.T.; Scholle, S.H. Evaluation of a Chronic Pain Screening Program Implemented in Primary Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2118495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.C.; Fillingim, R.B.; Ohrbach, R.; Patel, K.V. Assessment of Psychosocial and Functional Impact of Chronic Pain. J. Pain 2016, 17, T21–T49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haywood, K.L.; Mars, T.S.; Potter, R.; Patel, S.; Matharu, M.; Underwood, M. Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.; Pourkazemi, F.; Turton, J.; Rooney, K. Dietary Interventions Are Beneficial for Patients with Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Bruggink, L.; Malfliet, A.; Hayes, C.; Hodson, F.J.; Collins, C.E. Diet and Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: The State of the Art and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.E.; Faurot, K.R.; Zamora, D.; Suchindran, C.M.; MacIntosh, B.A.; Gaylord, S.; Ringel, A.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Feldstein, A.E.; Mori, T.A.; et al. Targeted alteration of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for the treatment of chronic headaches: A randomized trial. Pain 2013, 154, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.E.; Zamora, D.; Faurot, K.R.; MacIntosh, B.; Horowitz, M.; Keyes, G.S.; Yuan, Z.-X.; Miller, V.; Lynch, C.; Honvoh, G.; et al. Dietary alteration of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids for headache reduction in adults with migraine: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2021, 374, n1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora, D.; Kenney, K.; Horowitz, M.; Cole, W.R.; MacIntosh, B.A.; Ar0rieux, J.P.; Dunlap, M.; Palsson, O.S.; Davis, C.; Moore, C.B.; et al. A High Omega-3, Low Omega-6 Diet Reduces Headache Frequency and Intensity in Persistent Post-Traumatic Headache: A Randomized Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2025, 42, 1719–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. n-3 PUFA and inflammation: From membrane to nucleus and from bench to bedside. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C.; Balas, L.; Bazan, N.G.; Brenna, J.T.; Chiang, N.; da Costa Souza, F.; Dalli, J.; Durand, T.; Galano, J.M.; Lein, P.J.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, G.; Hayashi, K.; Morishita, N.; Takeshita, M.; Ishii, C.; Suzuki, S.; Ishimine, R.; Kasuga, A.; Nakazawa, H.; Takamatsu, T.; et al. Experimental and Clinical Investigation of Cytokines in Migraine: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkum, J.M. Migraine Triggers and Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Review and Synthesis. Headache 2016, 56, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, E.; Montagnana, M.; Lippi, G. Platelets and migraine. Thromb. Res. 2014, 134, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. The Differential Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patan, M.J.; Kennedy, D.O.; Husberg, C.; Hustvedt, S.O.; Calder, P.C.; Middleton, B.; Khan, J.; Forster, J.; Jackson, P.A. Differential Effects of DHA- and EPA-Rich Oils on Sleep in Healthy Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redivo, D.D.B.; Jesus, C.H.A.; Sotomaior, B.B.; Gasparin, A.T.; Cunha, J.M. Acute antinociceptive effect of fish oil or its major compounds, eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on diabetic neuropathic pain depends on opioid system activation. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 111992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurot, K.R.; Park, J.; Miller, V.; Honvoh, G.; Domeniciello, A.; Mann, J.D.; Gaylord, S.A.; Lynch, C.E.; Palsson, O.; Ramsden, C.E.; et al. Dietary fatty acids improve perceived sleep quality, stress, and health in migraine: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 4, 1231054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.D.; Faurot, K.R.; MacIntosh, B.; Palsson, O.S.; Suchindran, C.M.; Gaylord, S.A.; Lynch, C.; Johnston, A.; Maiden, K.; Barrow, D.A.; et al. A sixteen-week three-armed, randomized, controlled trial investigating clinical and biochemical effects of targeted alterations in dietary linoleic acid and n-3 EPA+DHA in adults with episodic migraine: Study protocol. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 128, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, B.A.; Ramsden, C.E.; Honvoh, G.; Faurot, K.R.; Palsson, O.S.; Johnston, A.D.; Lynch, C.; Anderson, P.; Igudesman, D.; Zamora, D.; et al. Methodology for altering omega-3 EPA+DHA and omega-6 linoleic acid as controlled variables in a dietary trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3859–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2004, 24 (Suppl. S1), 9–160.

- Kosinski, M.; Bayliss, M.S.; Bjorner, J.B.; Ware, J.E.; Garber, W.H.; Batenhorst, A.; Cady, R.; Dahlöf, C.G.H.; Dowson, A.; Tepper, S. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: The HIT-6. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, A.K.; Coeytaux, R.R.; Devellis, R.F.; Finkel, A.G.; Mann, J.D.; Kahn, K. Psychometric properties of the HIT-6 among patients in a headache-specialty practice. Headache 2005, 45, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houts, C.R.; McGinley, J.S.; Wirth, R.J.; Cady, R.; Lipton, R.B. Reliability and validity of the 6-item Headache Impact Test in chronic migraine from the PROMISE-2 study. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smelt, A.F.; Assendelft, W.J.; Terwee, C.B.; Ferrari, M.D.; Blom, J.W. What is a clinically relevant change on the HIT-6 questionnaire? An estimation in a primary-care population of migraine patients. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houts, C.R.; Wirth, R.J.; McGinley, J.S.; Cady, R.; Lipton, R.B. Determining Thresholds for Meaningful Change for the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) Total and Item-Specific Scores in Chronic Migraine. Headache 2020, 60, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S.; et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HealthMeasures. Pain Interference Scoring Manual. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Pain_Interference_Scoring_Manual.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Nagaraja, V.; Mara, C.; Khanna, P.P.; Namas, R.; Young, A.; Fox, D.A.; Laing, T.; McCune, W.J.; Dodge, C.; Rizzo, D.; et al. Establishing clinical severity for PROMIS((R)) measures in adult patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiotis, P.P.; Welsh, S.O.; Cronin, F.J.; Kelsay, J.L.; Mertz, W. Number of days of food intake records required to estimate individual and group nutrient intakes with defined confidence. J. Nutr. 1987, 117, 1638–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Olendzki, B.C.; Pagoto, S.L.; Hurley, T.G.; Magner, R.P.; Ockene, I.S.; Schneider, K.L.; Merriam, P.A.; Hebert, J.R. Number of 24-hour diet recalls needed to estimate energy intake. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, N.; Sekikawa, A.; Miura, K.; Evans, R.W.; Okuda, N.; Fujiyoshi, A.; Yoshita, K.; Chan, Q.; Okami, Y.; Kadota, A.; et al. Circulating plasma phospholipid fatty acid levels as a biomarker of habitual dietary fat intake: The INTERMAP/INTERLIPID Study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Tinker, L.F.; Huang, Y.; Neuhouser, M.L.; McCann, S.E.; Seguin, R.A.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Curb, J.D.; Prentice, R.L. Factors relating to eating style, social desirability, body image and eating meals at home increase the precision of calibration equations correcting self-report measures of diet using recovery biomarkers: Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihejirika, S.A.; Chiang, A.H.; Singh, A.; Stephen, E.; Chen, H.; Ye, K. A multi-level gene-diet interaction analysis of fish oil and 14 polyunsaturated fatty acid traits identifies the FADS and GPR12 loci. HGG Adv. 2025, 6, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-F.; Liu, W.-C.; Zailani, H.; Yang, C.-C.; Chen, T.-B.; Chang, C.-M.; Tsai, I.J.; Yang, C.-P.; Su, K.-P. A 12-week randomized double-blind clinical trial of eicosapentaenoic acid intervention in episodic migraine. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 118, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.d.A.; Louçana, P.M.C.; Nasi, E.P.; Sousa, K.M.d.H.; Sá, O.M.d.S.; Silva-Néto, R.P. A double- blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (OPFA ω-3) for the prevention of migraine in chronic migraine patients using amitriptyline. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.E.; O’Connell, N.; Pierce, C.R.; Estave, P.; Penzien, D.B.; Loder, E.; Zeidan, F.; Houle, T.T. Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation vs headache education for adults with migraine: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, T.; Chibueze, J.; Pester, B.D.; Saini, R.; Bar, N.; Edwards, R.R.; Adams, M.C.B.; Silver, J.K.; Meints, S.M.; Burton-Murray, H. Age, Race, Ethnicity, and Sex of Participants in Clinical Trials Focused on Chronic Pain. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, C.E.; Younis, S.; Deen, M.; Khan, S.; Ghanizada, H.; Ashina, M. Migraine induction with calcitonin gene-related peptide in patients from erenumab trials. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Li, N.; Dou, H.; Han, H.; Suo, M.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Rong, R.; et al. Circulating CGRP as a diagnostic biomarker in female migraine patients: A single-center case-control study. J. Headache Pain 2025, 26, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total | Intervention | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 38.3 (12.0) | 39.1 (11.8) | 36.9 (12.5) |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 29.2 (7.5) | 29.0 (7.7) | 29.5 (7.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or living with a partner | N (%) | 119 (66.5) | 76 (63.9) | 43 (71.7) |

| Single or widowed or divorced/separated | N (%) | 60 (33.5) | 43 (36.1) | 17 (28.3) |

| Highest education level | ||||

| High school or less | N (%) | 13 (7.2) | 9 (7.4) | 4 (6.8) |

| Undergraduate degree | N (%) | 109 (60.6) | 72 (59.5) | 37 (62.7) |

| Graduate degree | N (%) | 58 (32.2) | 40 (33.1) | 18 (30.5) |

| Income | ||||

| $41K and more | N (%) | 108 (61.0) | 76 (65.0) | 32 (53.3) |

| $40K and less | N (%) | 69 (39.0) | 41 (35.0) | 28 (46.7) |

| Race | ||||

| White | N (%) | 138 (75.8) | 91 (74.6) | 47 (78.3) |

| Black/African American | N (%) | 33 (18.1) | 22 (18.0) | 11 (18.3) |

| Asian/Native American/Pacific Islander | N (%) | 11 (6.0) | 9 (7.4) | 2 (3.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | N (%) | 161 (88.5) | 109 (89.3) | 52 (86.7) |

| Male | N (%) | 21 (11.5) | 13 (10.7) | 8 (13.3) |

| Latent Variables | Observed Variables | N | Min | Max | Mean (SD) | Difference (W16 − W0) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-3 intake | |||||||

| EPA intake (g) | 0.2 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 179 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 (0.1) | |||

| Week 16 | 143 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 (0.3) | |||

| DHA intake (g) | 0.6 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 179 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.1 (0.1) | |||

| Week 16 | 143 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.7 (0.7) | |||

| n-3 biomarkers | |||||||

| Blood EPA | |||||||

| EPA n3 WBC level (log ng/mL) | 1.6 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 168 | 0.3 | 11.5 | 2.4 (1.9) | |||

| Week 16 | 135 | 0.5 | 17.7 | 4.0 (3.4) | |||

| EPA n3 Plasma level (log ng/mL) | 8.4 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 172 | 2.2 | 43.7 | 11.6 (6.3) | |||

| Week 16 | 125 | 2.9 | 63.2 | 19.9 (13.0) | |||

| Blood DHA | DHA n3 WBC level (log ng/mL) | 2.6 | <0.01 | ||||

| Baseline | 168 | 1.02 | 40.4 | 6.5 (5.4) | |||

| Week 16 | 135 | 1.03 | 43.1 | 9.3 (6.8) | |||

| DHA n3 Plasma level (log ng/mL) | 19.2 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 172 | 12.0 | 109.1 | 35.4 (13.2) | |||

| Week 16 | 125 | 11.7 | 136.8 | 54.1 (25.8) | |||

| Pain Interference | |||||||

| Hit-6 score (36–78) | −4.1 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 182 | 40.0 | 78.0 | 62.7 (5.3) | |||

| Week 16 | 138 | 38.0 | 78.0 | 59.0 (7.0) | |||

| PROMIS pain interference t-score | −4.6 | <0.01 | |||||

| Baseline | 182 | 41.6 | 75.6 | 59.0 (6.8) | |||

| Week 16 | 138 | 41.6 | 75.6 | 54.5 (8.1) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, J.; Kadro, Z.O.; Honvoh, G.D.; Domeniciello, A.F.; Ramsden, C.E.; Faurot, K.R.; Miller, V.E. Associations Between Dietary Intakes of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Blood Levels, and Pain Interference in People with Migraine: A Path Analysis of Randomized Trial Data. Nutrients 2026, 18, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010003

Park J, Kadro ZO, Honvoh GD, Domeniciello AF, Ramsden CE, Faurot KR, Miller VE. Associations Between Dietary Intakes of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Blood Levels, and Pain Interference in People with Migraine: A Path Analysis of Randomized Trial Data. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010003

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jinyoung, Zachary O. Kadro, Gilson D. Honvoh, Anthony F. Domeniciello, Christopher E. Ramsden, Keturah R. Faurot, and Vanessa E. Miller. 2026. "Associations Between Dietary Intakes of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Blood Levels, and Pain Interference in People with Migraine: A Path Analysis of Randomized Trial Data" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010003

APA StylePark, J., Kadro, Z. O., Honvoh, G. D., Domeniciello, A. F., Ramsden, C. E., Faurot, K. R., & Miller, V. E. (2026). Associations Between Dietary Intakes of Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Blood Levels, and Pain Interference in People with Migraine: A Path Analysis of Randomized Trial Data. Nutrients, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010003