Eating Disorder Symptoms in the Context of Perfectionism and Sociocultural Internalization: A Profile Analysis and Mediation Approach

Abstract

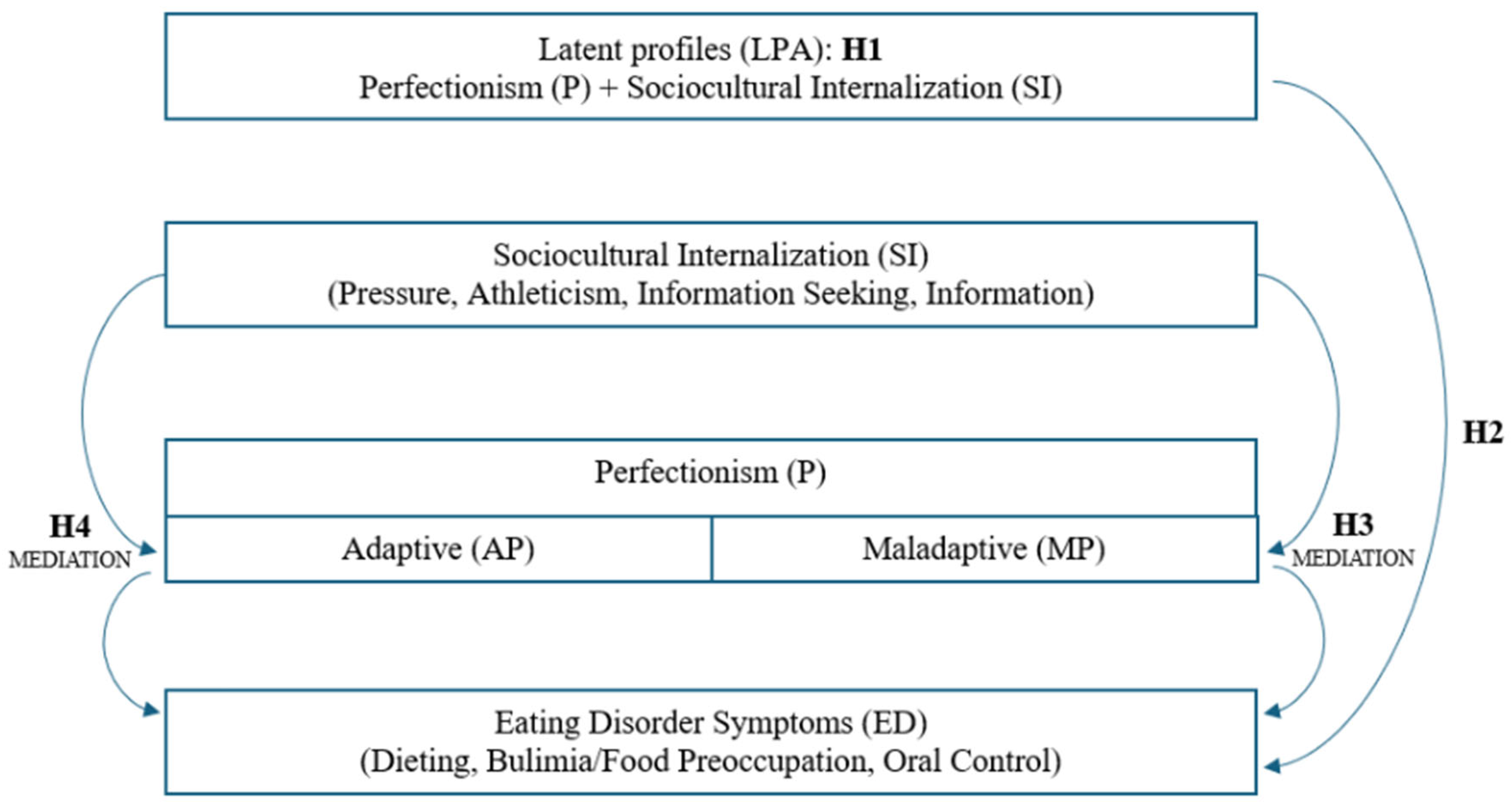

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

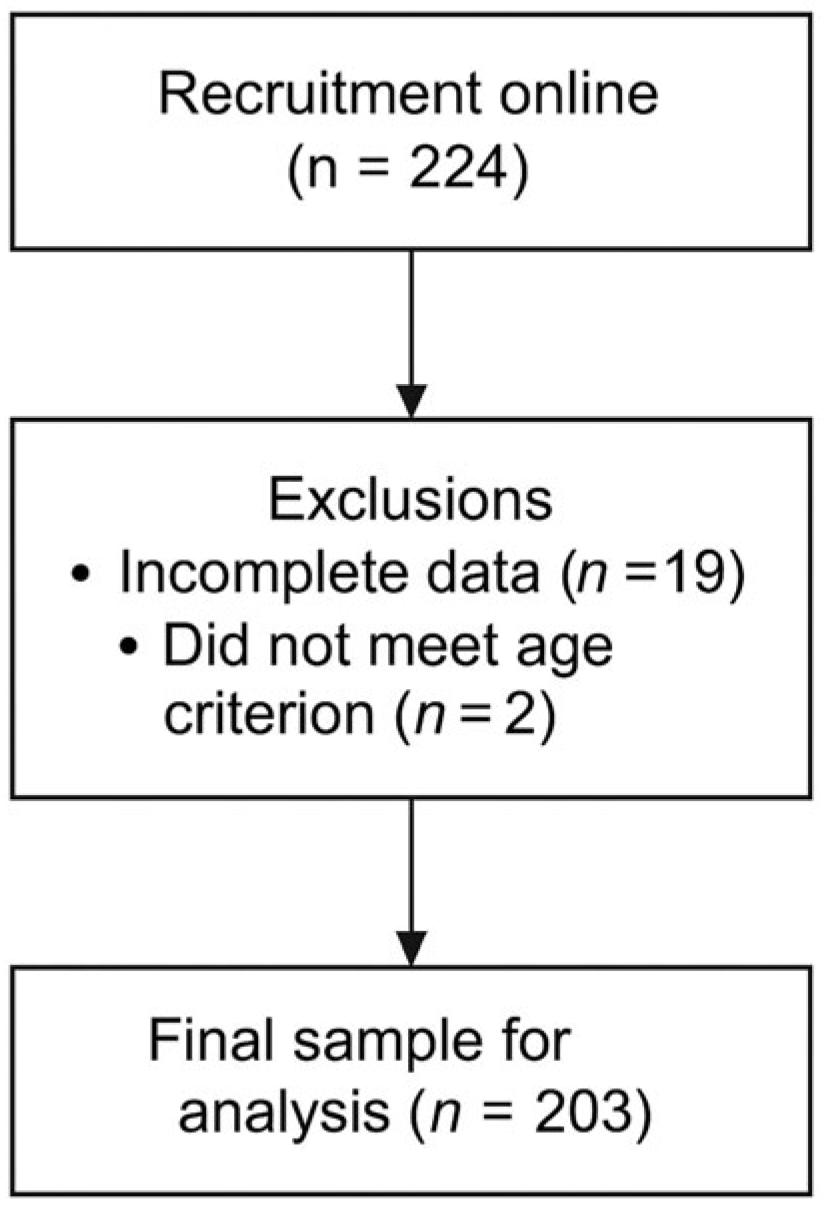

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Eating Disorder Risk

2.3.2. Perfectionism

2.3.3. Sociocultural Internalization

2.3.4. Demographics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Latent Profile Analysis

3.2. Profiles and Eating Disorders

3.3. Mediating Role of Perfectionism

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

5. Implications for Practice

- Psychoeducational programs aimed at developing critical thinking regarding media messages and cultural norms;

- Strategies to strengthen psychological resilience and promote a realistic body image;

- Therapeutic interventions addressing maladaptive perfectionism mechanisms, such as fear of evaluation and excessively high self-imposed standards.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Bulik, C.M. Risk factors for eating disorders. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Wajda, Z.; Lizińczyk, S.; Ściegienny, A. Bonding with parents, body image, and sociocultural attitudes toward appearance as predictors of eating disorders among young girls. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 590542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, P.K.; Forney, K.J. Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.Q. The internalization of moral norms. Sociometry 1964, 27, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeln, R. Beauty Sick: How the Cultural Obsession with Appearance Hurts Girls and Women; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stice, E.; van Ryzin, M.J. A prospective test of the temporal sequencing of risk factor emergence in the dual pathway model of eating disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbierik, L.; Bacikova-Sleskova, M.; Petrovova, V. The role of social appearance comparison in body dissatisfaction of adolescent boys and girls. Eur. J. Psychol. 2023, 19, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Lennon, S.J. Mass media and self-esteem, body image, and eating disorder tendencies. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2007, 25, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynthia, M.; Bulik, M.A. Eating disorders in immigrants: Two case reports. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamachek, D.E. Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psychol. J. Hum. Behav. 1978, 15, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Caelian, C.F.; Flett, G.L.; Sherry, S.B.; Collins, L.; Flynn, C.A. Perfectionism in children: Associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S.C.; Gleaves, D.H.; Hutchinson, A.D. Anorexia nervosa and perfectionism: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. (Ed.) The Psychology of Perfectionism: Theory, Research, Applications; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Świerczyńska, J. Coexistence of the features of perfectionism and anorexia readiness in school youth. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Karvinen, K.; McCreary, D.R. Personality correlates of a drive for muscularity in young men. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafran, R.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, R.; Farr, M.; Hiramatsu, I.; Quinton, S. Symptoms of muscle dysmorphia and eating disorders in men, and the mediating effects of perfectionism. Behav. Med. 2016, 42, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassaroli, S.; Apparigliato, M.; Bartelli, S.; Boccalari, L.; Fiore, F.; Lamela, C.; Scarone, S.; Ruggiero, G.M. Perfectionism as a mediator between perceived criticism and eating disorders. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2011, 16, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Contentezza, R.; Casella, M.; Cernigliaro, A.; Cosentini, I.; Drago, G.; Coco, G.L.; Semola, M.R.; Gullo, S. Social and individual factors associated with eating disorders risk among adolescents in secondary schools of Sicily (South-Italy). Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2025, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, O.; Detopoulou, P.; Fappa, E.; Perrea, A.; Levidi, D.; Dedes, V.; Tzoutzou, M.; Gioxari, A.; Panoutsopoulos, G. Eating attitudes, stress, anxiety, and depression in dietetic students and association with body mass index and body fat percent. Diseases 2024, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K. Sociocultural appearance standards and risk factors for eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogoza, R.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Garner, D.M. Analysis of the EAT-26 in a nonclinical sample. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2016, 18, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczucka, K. Polski Kwestionariusz Perfekcjonizmu Adaptacyjnego i Dezadaptacyjnego. Psychol. Społeczna 2010, 5, 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.K.; van den Berg, P.; Roehrig, M.; Guarda, A.S.; Heinberg, L.J. The Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Lizińczyk, S. The Polish adaptation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance SATAQ-3 Questionnaire. Health Psychol. Rep. 2020, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tein, J.Y.; Coxe, S.; Cham, H. Statistical Power to Detect the Correct Number of Classes in Latent Profile Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2013, 20, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, J.M. Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: Graphical causal models for observational data. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 1, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.P.; Nelson, L.D.; Simonsohn, U. False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackpole, R.; Greene, D.; Bills, E.; Egan, S.J. The association between eating disorders and perfectionism in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B.F.; Kiss, H.; Gráczer, A.; Fitzpatrick, K.M. Risk of disordered eating in emerging adulthood: Media, body and weight-related correlates among Hungarian female university students. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E83–E89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashy, J.; Culbert, K.M. The role of distinct facets of perfectionism and sociocultural idealization of thinness on disordered eating symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 38, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 25.09 (3.52) |

| BMI, M (SD) | 22.18 (5.14) |

| Height, M (SD) | 1.66 (0.07) |

| Body weight, M (SD) | 61.58 (15.38) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Primary education | 3 (1.5%) |

| Basic vocational education | 2 (1.0%) |

| Secondary education | 36 (17.7%) |

| Currently pursuing higher education | 85 (41.9%) |

| Higher education | 77 (37.9%) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed | 84 (41.4%) |

| Unemployed | 2 (1.0%) |

| Student | 55 (27.1%) |

| Student and employed | 61 (30.0%) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.5%) |

| Place of residence, n (%) | |

| Rural area | 24 (11.8%) |

| City up to 100.000 inhabitants | 44 (21.7%) |

| City from 100.000 to 250.000 inhabitants | 31 (15.3%) |

| City from 250.000 to 500.000 inhabitants | 44 (21.7%) |

| City over 500.000 inhabitants | 60 (29.6%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 59 (29.1%) |

| In an informal relationship | 106 (52.2%) |

| In a formal relationship/married | 35 (17.2%) |

| Other | 3 (1.5%) |

| Model | Classes | LogLik | AIC | AWE | BIC | CAIC | CLC | KIC | SABIC | ICL | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | −1580 | 3199 | 3418 | 3262 | 3281 | 3162 | 3221 | 3201 | −3284 | 0.837 |

| 1 | 3 | −1530 | 3112 | 3413 | 3198 | 3224 | 3062 | 3141 | 3116 | −3228 | 0.859 |

| 2 | 2 | −1545 | 3141 | 3430 | 3224 | 3249 | 3093 | 3169 | 3144 | −3237 | 0.890 |

| 2 | 3 | −1524 | 3123 | 3563 | 3249 | 3287 | 3049 | 3164 | 3129 | −3271 | 0.903 |

| 3 | 2 | −1490 | 3048 | 3442 | 3161 | 3195 | 2982 | 3085 | 3053 | −3192 | 0.783 |

| 3 | 3 | −1479 | 3040 | 3515 | 3176 | 3217 | 2960 | 3084 | 3046 | −3226 | 0.767 |

| 6 | 2 | −1404 | 2917 | 3555 | 3099 | 3154 | 2809 | 2975 | 2925 | −3106 | 0.932 |

| 6 | 3 | −1367 | 2901 | 3864 | 3176 | 3259 | 2737 | 2987 | 2913 | −3185 | 0.943 |

| Profile1 (n = 47) | Profile 2 (n = 140) | Profile 3 (n = 16) | Post Hoc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | H(2) | p | η2 | |

| Maladaptive perfectionism | 62.51 | 55.00 | 51.00 | 112.76 | 93.50 | 43.75 | 123.88 | 92.00 | 39.75 | 28.16 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 1–2 p < 0.001; 1–3 p = 0.001 |

| Adaptive perfectionism | 96.40 | 64.00 | 16.00 | 98.56 | 65.50 | 19.00 | 148.53 | 74.00 | 9.75 | 10.95 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 1–3 p = 0.006 2–3 p = 0.004 |

| Internalization—Pressure | 30.87 | 14.00 | 6.00 | 118.61 | 33.00 | 19.00 | 165.63 | 45.50 | 8.50 | 99.04 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 1–2 p < 0.001 1–3 p < 0.001 2–3 p = 0.007 |

| Internalization—Athleticism | 54.95 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 109.51 | 13.00 | 6.00 | 174.53 | 18.00 | 3.50 | 57.08 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 1–2–3 p < 0.001 |

| Internalization—Information Seeking | 61.79 | 10.00 | 9.00 | 108.86 | 17.00 | 7.00 | 160.06 | 22.00 | 3.50 | 39.70 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 1–2 p < 0.001 1–3 p < 0.001 2–3 p = 0.003 |

| Internalization—Information | 29.64 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 122.16 | 13.00 | 8.00 | 138.16 | 15.00 | 4.00 | 95.04 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 1–2 p < 0.001 1–3 p < 0.001 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Maladaptive perfectionism | 65.02 | 33.34 | 94.16 | 27.49 | 100.44 | 30.79 |

| Adaptive perfectionism | 63.43 | 15.10 | 64.42 | 13.68 | 74.25 | 5.89 |

| Internalization—Pressure | 15.04 | 3.28 | 34.27 | 12.18 | 46.19 | 8.50 |

| Internalization—Athleticism | 8.45 | 4.06 | 13.07 | 4.21 | 18.06 | 1.57 |

| Internalization—Information Seeking | 12.45 | 6.65 | 17.18 | 4.96 | 21.94 | 3.40 |

| Internalization—Information | 6.23 | 0.43 | 14.02 | 5.63 | 15.00 | 3.85 |

| Profile 1 (n = 47) | Profile 2 (n = 140) | Profile 3 (n = 16) | Post Hoc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | Mean Rank | Mdn | IQR | H(2) | p | η2 | |

| ED | 76.13 | 9.00 | 10.00 | 105.51 | 13.50 | 12.00 | 147.31 | 20.50 | 15.50 | 19.18 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 1–2 p = 0.009 1–3 p < 0.001 2–3 p = 0.021 |

| Dieting | 78.62 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 104.43 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 149.41 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 18.18 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 1–2 p = 0.027 1–3 p < 0.001 2–3 p = 0.011 |

| Bulimia/food preoccupation | 76.28 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 106.37 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 139.31 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 17.22 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 1–2 p = 0.005 1–3 p < 0.001 2–3 p = 0.086 |

| Oral control | 93.77 | 0.14 | 0.57 | 102.73 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 119.81 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 2.53 | 0.283 | <0.01 | |

| CI 95% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Effect a | B | SE | t | p | LL | UL |

| Model 1—Internalization—Pressure | a | 1.22 | 0.13 | 9.09 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 1.49 |

| b | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.75 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| c | 0.34 | 0.04 | 7.56 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.44 | |

| c’ | 0.21 | 0.05 | 4.13 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.31 | |

| c–c’ | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.20 | |||

| Model 2—Internalization—Athleticism | a | 2.00 | 0.45 | 4.47 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 2.89 |

| b | 0.14 | 0.02 | 7.05 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.19 | |

| c | 0.58 | 0.15 | 3.94 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.87 | |

| c’ | 0.28 | 0.14 | 2.07 | 0.040 | 0.01 | 0.56 | |

| c–c’ | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.47 | |||

| Model 3—Internalization—Information Seeking | a | 1.56 | 0.36 | 4.27 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 2.28 |

| b | 0.14 | 0.02 | 7.06 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.18 | |

| c | 0.48 | 0.12 | 4.04 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.71 | |

| c’ | 0.25 | 0.11 | 2.27 | 0.024 | 0.03 | 0.47 | |

| c–c’ | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.36 | |||

| Model 4—Internalization—Information | a | 2.08 | 0.35 | 5.90 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 2.78 |

| b | 0.15 | 0.02 | 7.08 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.19 | |

| c | 0.40 | 0.12 | 3.35 | 0.001 | 0,17 | 0.64 | |

| c’ | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.464 | −0.14 | 0.32 | |

| c–c’ | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.46 | |||

| CI 95% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Effect a | B | SE | t | p | LL | UL |

| Model 1—Internalization—Pressure | a | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.97 | 0.051 | −0.01 | 0.27 |

| b | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.74 | 0.084 | −0.01 | 0.17 | |

| c | 0.34 | 0.04 | 7.56 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.44 | |

| c’ | 0.33 | 0.04 | 7.29 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.42 | |

| c–c’ | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | |||

| Model 2—Internalization—Athleticism | a | 0.80 | 0.20 | 4.09 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 1.19 |

| b | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.49 | 0.138 | −0.02 | 0.18 | |

| c | 0.58 | 0.15 | 3.94 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.86 | |

| c’ | 0.51 | 0.15 | 3.38 | 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.81 | |

| c–c’ | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.16 | |||

| Model 3—Internalization—Information Seeking | a | −0.07 | 0.17 | −0.42 | 0.673 | −0.40 | 0.26 |

| b | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.68 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.23 | |

| c | 0.48 | 0.12 | 4.04 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.71 | |

| c’ | 0.49 | 0.12 | 4.18 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.72 | |

| c–c’ | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.02 | |||

| Model 4—Internalization—Information | a | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.89 | 0.376 | −0.18 | 0.47 |

| b | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.31 | 0.022 | 0.02 | 0.22 | |

| c | 0.40 | 0.12 | 3.35 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.64 | |

| c’ | 0.39 | 0.12 | 3.24 | 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.62 | |

| c–c’ | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szymajda, K.; Chęć, M.; Michałowska, S. Eating Disorder Symptoms in the Context of Perfectionism and Sociocultural Internalization: A Profile Analysis and Mediation Approach. Nutrients 2026, 18, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010161

Szymajda K, Chęć M, Michałowska S. Eating Disorder Symptoms in the Context of Perfectionism and Sociocultural Internalization: A Profile Analysis and Mediation Approach. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzymajda, Karolina, Magdalena Chęć, and Sylwia Michałowska. 2026. "Eating Disorder Symptoms in the Context of Perfectionism and Sociocultural Internalization: A Profile Analysis and Mediation Approach" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010161

APA StyleSzymajda, K., Chęć, M., & Michałowska, S. (2026). Eating Disorder Symptoms in the Context of Perfectionism and Sociocultural Internalization: A Profile Analysis and Mediation Approach. Nutrients, 18(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010161