Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Testing of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

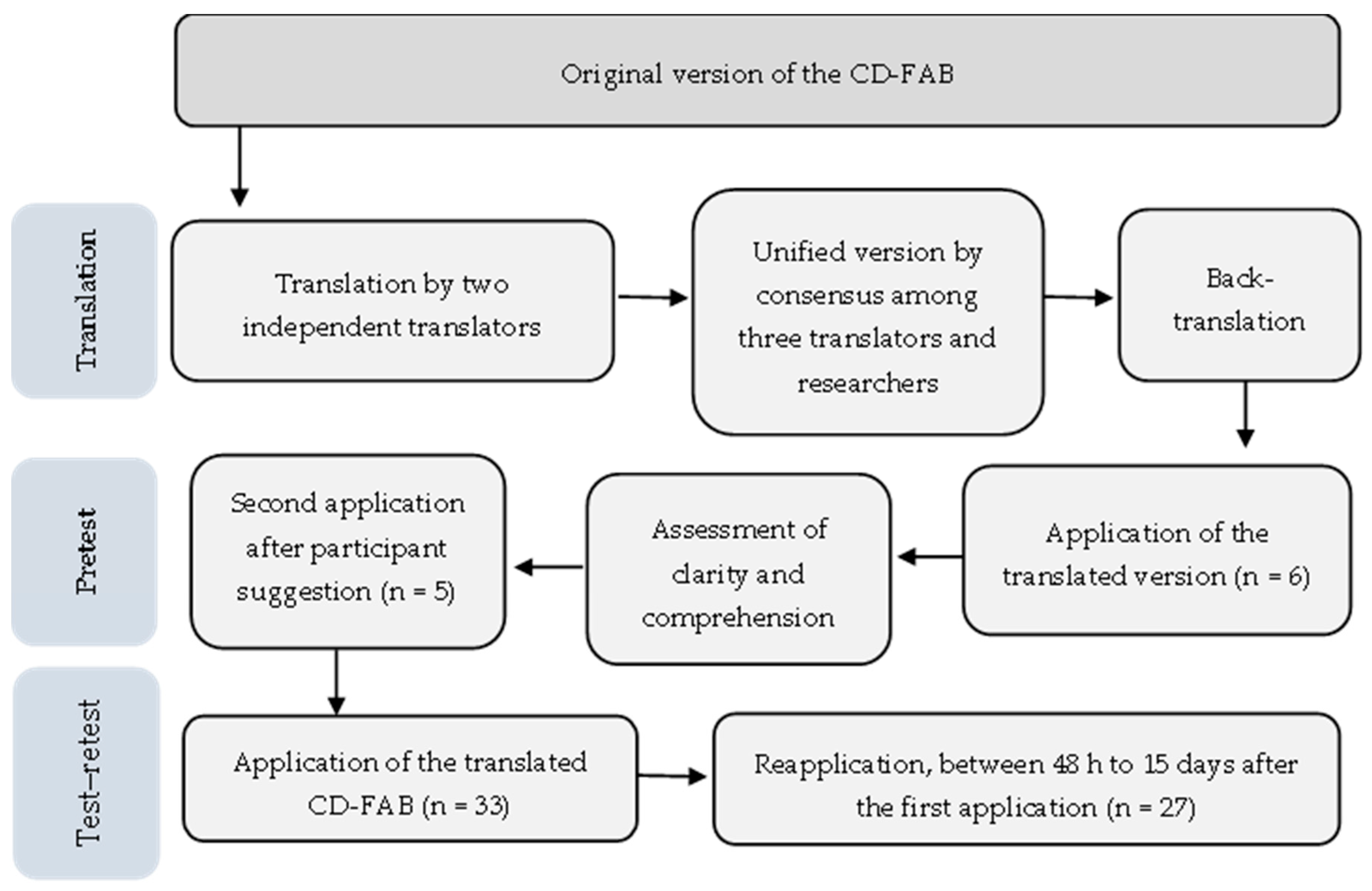

2.2. Translation and Cultural Adaptation of the CD-FAB

2.3. Pretest

2.4. Psychometric Evaluation of the Brazilian Version of CD-FAB

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pretest

3.2. Reproducibility and Internal Consistency of the CD-FAB-BR

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sahin, Y. Celiac Disease in Children: A Review of the Literature. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzlinger, A.; Branchi, F.; Elli, L.; Schumann, M. Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease—Forever and for All? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elli, L.; Leffler, D.; Cellier, C.; Lebwohl, B.; Ciacci, C.; Schumann, M.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Chetcuti Zammit, S.; Sidhu, R.; Roncoroni, L.; et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines Guidelines for Best Practices in Monitoring Established Coeliac Disease in Adult Patients. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Publishing. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo, C.M. Eating and Weight Disorders; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781317821878. [Google Scholar]

- Satherley, R.; Howard, R.; Higgs, S. Disordered Eating Practices in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Appetite 2015, 84, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, R.; Mahdavi, R.; Shirmohammadi, M.; Nikniaz, Z. Eating Disorders, Body Image Dissatisfaction and Their Association with Gluten-Free Diet Adherence among Patients with Celiac Disease. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikniaz, Z.; Beheshti, S.; Abbasalizad Farhangi, M.; Nikniaz, L. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence and Odds of Eating Disorders in Patients with Celiac Disease and Vice-Versa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberland, M.; Rochette, S.; Carbonneau, N.; Gagnon-Girouard, M.P. Development and Validation of the Eating Beliefs and Behaviors Questionnaire for Gastrointestinal Disorders (EBBQ-GID). Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 74, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokatly Latzer, I.; Lerner-Geva, L.; Stein, D.; Weiss, B.; Pinhas-Hamiel, O. Disordered Eating Behaviors in Adolescents with Celiac Disease. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.E.; Basnayake, C.; Hebbard, G.S.; Salzberg, M.R.; Kamm, M.A. Prevalence of Disordered Eating in Adults with Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 34, e14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The Assessment of Binge Eating Severity among Obese Persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric Features and Clinical Correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmstead, M.P.; Polivy, J. Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Eating Disorder Inventory for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1983, 2, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passananti, V.; Siniscalchi, M.; Zingone, F.; Bucci, C.; Tortora, R.; Iovino, P.; Ciacci, C. Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Adults with Celiac Disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 491657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Zybert, P.; Chen, Z.; Lebovits, J.; Wolf, R.L.; Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R. Food Avoidance beyond the Gluten-Free Diet and the Association with Quality of Life and Eating Attitudes and Behaviors in Adults with Celiac Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Bery, A.; Esposito, P.; Zickgraf, H.; Adams, D.W. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Characteristics and Prevalence in Adult Celiac Disease Patients. Gastro Hep Adv. 2022, 1, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, R.L.; Lebwohl, B.; Lee, A.R.; Zybert, P.; Reilly, N.R.; Cadenhead, J.; Amengual, C.; Green, P.H.R. Hypervigilance to a Gluten-Free Diet and Decreased Quality of Life in Teenagers and Adults with Celiac Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satherley, R.M.; Howard, R.; Higgs, S. Development and Validation of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 6930269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholmie, Y.; Lee, A.R.; Satherley, R.M.; Schebendach, J.; Zybert, P.; Green, P.H.R.; Lebwohl, B.; Wolf, R. Maladaptive Food Attitudes and Behaviors in Individuals with Celiac Disease and Their Association with Quality of Life. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toruş, R.; Ede, G.; Serin, Y.; Tayhan Kartal, F. Çölyak Hastalığı Besin Tutum ve Davranışları Ölçeği’nin Türkçe’ye Uyarlanması: Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Avrasya Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2023, 6, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abber, S.R.; Burton Murray, H. Does Gluten Avoidance in Patients with Celiac Disease Increase the Risk of Developing Eating Disorders? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 2790–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Lebwohl, B.; Lebovits, J.; Wolf, R.L.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Green, P.H.R. Factors Associated with Maladaptive Eating Behaviors, Social Anxiety, and Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FENACELBRA. Prevalência Da Doença Celíaca No Brasil. Available online: https://www.fenacelbra.com.br/prevalencia-da-doenca-celiaca (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Machado, J.; Gandolfi, L.; Coutinho de Almeida, F. Parámetros Antropométricos Como Indicadores de Riesgo Para La Salud En Universitarios. Nutr. Clínica Y Dietética Hosp. 2013, 33, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.d.S.; Uenishi, R.H.; Domingues, A.d.S.; Nakano, E.Y.; Botelho, R.B.A.; Raposo, A.; Zandonadi, R.P. Gluten-Free Diet Adherence Tools for Individuals with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Tools Compared to Laboratory Tests. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; Beltrán-Cárdenas, C.E.; André, T.G.; Gomes, I.C.; Macêdo-Callou, M.A.; Braga-Rocha, É.M.; Mye-Takamatu-watanabe, E.A.; Rahmeier-Fietz, V.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.d.J.; et al. Prevalence of Adverse Reactions to Glutenand People Going on a Gluten-Free Diet:A Survey Study Conducted in Brazil. Medicina 2020, 56, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NEEDs Center. Protocol for the Use of the EcSatter Inventory 2.0; NEEDs Center: Andover, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McIntire, S.A.; Miller, L.A. Test-Retest Reliability. In Foundations of Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Dusi, R.; Botelho, R.B.A.; Nakano, E.Y.; de Queiroz, F.L.N.; Zandonadi, R.P. Translation of the Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding Questionnaire into Brazilian Portuguese: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, B.; Satter, E. Use of an Observational Comparative Strategy Demonstrated Construct Validity of a Measure to Assess Adherence to the Satter Division of Responsibility in Feeding. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1143–1156.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, B.; Mitchell, D.C. Valid and Reliable Measure of Adherence to Satter Division of Responsibility in Feeding. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEEDs Center. EcSI-2.0-Translation-Guide-2. Available online: https://www.needscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ecSI-2.0-Translation-Guide-2.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bartlett, J.W.; Frost, C. Reliability, Repeatability and Reproducibility: Analysis of Measurement Errors in Continuous Variables. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 31, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales, 5th ed.; Oxford, Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 1, ISBN 9780199685219. [Google Scholar]

- Stevelink, S.A.M.; Van Brakel, W.H. The Cross-Cultural Equivalence of Participation Instruments: A Systematic Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, C.B.; Ambrogi, F.; Sardanelli, F. Sample Size Calculation for Data Reliability and Diagnostic Performance: A Go-to Review. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2024, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, R.G.; Menezes, A.; Horovitz, L.; Jones, E.C.; Warren, R.F. A Comparison of Two Time Intervals for Test-Retest Reliability of Health Status Instruments. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780199231881. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780195165678. [Google Scholar]

- Nisihara, R.; Techy, A.C.M.; Staichok, C.; Roth, T.C.; de Biassio, G.F.; Cardoso, L.R.; da Silva Kotze, L.M. Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Comparative Study with Healthy Individuals. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20231090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwautz, A.; Wagner, G.; Berger, G.; Sinnreich, U.; Grylli, V.; Huber, W.D. Eating Pathology in Adolescents with Celiac Disease. Psychosomatics 2008, 49, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, C.; Almilaji, O.; Nicholas, D.; Kirkham, S.; Surgenor, S.L.; Williams, I.; Snook, J. Evolving Patterns in the Presentation of Coeliac Disease over the Last 25 Years. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenhead, J.W.; Wolf, R.L.; Lebwohl, B.; Lee, A.R.; Zybert, P.; Reilly, N.R.; Schebendach, J.; Satherley, R.; Green, P.H.R. Diminished Quality of Life among Adolescents with Coeliac Disease Using Maladaptive Eating Behaviours to Manage a Gluten-Free Diet: A Cross-Sectional, Mixed-Methods Study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Leffler, D. Celiac Disease: An Underappreciated Issue in Womens Health. Women’s Health 2010, 6, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satherley, R.M.; Howard, R.; Higgs, S. The Prevalence and Predictors of Disordered Eating in Women with Coeliac Disease. Appetite 2016, 107, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Foo, D.H.P.; Hon, Y.K. Sample Size Determination for Conducting a Pilot Study to Assess Reliability of a Questionnaire. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2024, 49, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Response Options and Items | English Original | Translation 1 | Translation 2 | Translation 1–2 | English Back-Translation | Revised Translation After Pretest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directions | Instructions: This questionnaire is designed to explore food attitudes and beliefs in coeliac disease. | Instruções: Este questionário foi pensado pra explorar atitudes alimentares e crenças na doença celíaca. | Instruções: este questionário é projetado para explorar atitudes e crenças alimentares relacionadas à doença celíaca. | Este questionário foi desenvolvido para explorar atitudes e crenças alimentares relacionadas à doença celíaca | This questionnaire was developed to explore dietary attitudes and beliefs related to coeliac disease. | Este questionário foi desenvolvido para explorar atitudes e crenças alimentares relacionadas à doença celíaca. |

| Some questions may not apply to you; this is because we are trying to assess a range of beliefs about coeliac disease and managing the gluten-free diet. | Algumas perguntas podem não se aplicar a você; isso ocorre porque estamos tentando avaliar uma série de crenças sobre a doença celíaca e o manejo da dieta sem glúten. | Algumas perguntas podem não se aplicar a você; isso ocorre porque estamos tentando avaliar uma variedade de crenças sobre a doença celíaca e sobre como administrar a dieta livre de glúten. | Algumas perguntas podem não se aplicar a você; isso ocorre porque estamos tentando avaliar uma série de crenças sobre a doença celíaca e como gerenciar a dieta sem glúten. | Some questions may not apply to you; this happens because we are trying to evaluate a range of beliefs about coeliac disease and how to manage a gluten-free diet. | Algumas perguntas podem não se aplicar a você; isso ocorre porque estamos tentando avaliar uma série de crenças sobre a doença celíaca e como gerenciar a dieta sem glúten. | |

| Please fill out the form below as accurately, honestly, and completely as possible. | Por favor, preencha o formulário abaixo da forma mais precisa, honesta e completa possível. | Por favor, preencha o formulário abaixo da forma mais precisa, honesta e completa possível. | Por favor, preencha o formulário abaixo da forma mais precisa, honesta e completa possível. | Please fill out the form below as accurately, truthfully, and completely as possible. | Por favor, preencha o formulário abaixo da forma mais precisa, honesta e completa possível. | |

| There are no right or wrong answers. | Não existem respostas certas ou erradas. | Não há respostas certas ou erradas. | Não existem respostas certas ou erradas. | There are no right or wrong answers. | Não existem respostas certas ou erradas. | |

| All of your responses are confidential. | Todas as suas respostas são confidenciais. | Todas as tuas respostas são confidenciais. | Todas as suas respostas são confidenciais. | All your responses will be kept confidential by the researchers. | Todas as suas respostas são confidenciais. | |

| Please tick the box that best describes your response to the question. | Por favor, assinale a caixa que melhor descreve a sua resposta à questão. | Por favor, marque a caixa que melhor descreve sua resposta para a questão. | Por favor, marque a caixa que melhor descreve sua resposta para a questão. | Please mark the option that best describes your answer to each question. | Por favor, marque a caixa que melhor descreve sua resposta para a questão. | |

| Response options | Strongly agree (7) | Concordo muito (7) | Concordo muito (7) | Concordo muito (7) | strongly agree (7) | Concordo totalmente (7) |

| Agree (6) | Concordo (6) | Concordo (6) | Concordo (6) | Agree (6) | Concordo (6) | |

| Somewhat agree (5) | Concordo um pouco (5) | Concordo de alguma forma (5) | Concordo de alguma forma (5) | Slightly agree (5) | Concordo de alguma forma (5) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | Não concordo e nem discordo (4) | Nem concordo nem discordom (4) | Nem concordo nem discordo (4) | Neither agree nor disagree (4) | Nem concordo nem discordo (4) | |

| Somewhat disagree (3) | Discordo um pouco (3) | Discordo de alguma forma (3) | Discordo de alguma forma (3) | Slightly disagree (3) | Discordo de alguma forma (3) | |

| Disagree (2) | Discordo (2) | Discordo (2) | Discordo (2) | Disagree (2) | Discordo (2) | |

| Strongly disagree (1) | Discordo muito (1) | Discordo muito (1) | Discordo muito (1) | Strongly disagree (1) | Discordo totalmente (1) | |

| Items | 1—Because of my coeliac disease… | 1—Em razão da minha doença celíaca… | 1—Devido à minha doença celíaca… | 1—Devido a minha doença celíaca… | 1—Due to coeliac disease… | Devido à doença celíaca… |

| I get concerned being near others when they are eating gluten. | Eu fico preocupado estando perto de outras pessoas quando elas estão comendo glúten | Eu fico preocupado de estar perto de outras pessoas quando elas estão comendo glúten. | Eu fico preocupado de estar perto de outras pessoas quando elas estão comendo glúten. | I worry about being around other people when they are eating food that contains gluten. | eu fico preocupado de estar perto de outras pessoas quando elas estão comendo glúten. | |

| I am afraid to eat outside my home. | Eu tenho medo de comer fora da minha casa. | Eu tenho medo de comer fora de casa. | Eu tenho medo de comer fora de casa. | I am afraid of eating out. | eu tenho medo de comer fora de casa. | |

| I am afraid to touch gluten-containing foods. | Eu tenho medo de encostar em comidas que contêm gluten. | Eu tenho medo de entrar em contato com comidas que contêm glúten. | Eu tenho medo de entrar em contato com comidas que contêm glúten. | I am afraid of having contact with food that contains gluten. | eu tenho medo de entrar em contato com comidas que contêm glúten. | |

| I get worried when eating with strangers. | Eu fico preocupado quando como algo com pessoas estranhas. | Eu fico preocupado quando estou comendo com estranhos. | Eu fico preocupado quando como com estranhos. | I get worried when I am eating with strangers. | eu fico preocupado quando como com estranhos. | |

| I find it hard to eat gluten-free foods that look like the gluten-containing foods that made me ill in the past. | Acho difícil comer alimentos sem glúten que se pareçam com os alimentos que contêm glúten que me deixaram doente no passado. | Eu tenho dificuldade de comer comidas sem glúten que se parecem com as comidas com glúten que me adoeceram no passado. | Acho difícil comer alimentos sem glúten que parecem com os alimentos que contêm glúten que me deixaram doente no passado. | I found it is difficult to eat gluten-free foods that are similar to foods that contain gluten that have made me sick in the past. | acho difícil comer alimentos sem glúten que parecem com os alimentos que contêm glúten que me deixaram doente no passado. | |

| I will only eat food that I have prepared myself. | Eu só vou comer comida que eu mesmo preparei. | Eu só como comida que eu mesmo preparei. | Eu só como comida que eu mesmo preparei. | I only eat food prepared by myself. | Só como comida que eu mesmo preparo. | |

| My concerns about cross-contamination prevent me from going to social events involving food. | Minhas preocupações com a contaminação cruzada me impedem de ir a eventos sociais que envolvam alimentos. | Minhas preocupações sobre contaminação cruzada me impedem de ir a eventos sociais que envolvem comida. | Minhas preocupações com a contaminação cruzada me impedem de ir a eventos sociais que envolvam alimentos. | My concern with cross-contamination from gluten is attending social events that serve food. | Minhas preocupações com a contaminação cruzada me impedem de ir a eventos sociais que envolvam alimentos. | |

| 2—Despite having coeliac disease… | 2—Apesar de ter doença celíaca… | 2—Apesar de ter doença celíaca… | 2—Apesar de ter doença celíaca… | Despite having coeliac disease… | Apesar de ter doença celíaca… | |

| I enjoy going out for meals as much as I did before my diagnosis *. | Eu gosto de sair pra comer tanto quanto gostava antes de ser diagnosticada(o). | Eu gosto de sair para comer tanto quanto gostava de sair antes do meu diagnóstico. | Eu gosto de sair pra comer tanto quanto gostava antes de ser diagnosticada(o). | I like to go out to eat as much as I liked before the diagnosis. | Eu gosto de sair para comer tanto quanto gostava antes de ser diagnosticada(o). | |

| I am comfortable eating gluten-free food from other people’s kitchens *. | Sinto-me confortável comendo alimentos sem glúten da cozinha de outras pessoas *. | Eu fico confortável comendo comidas sem glúten da cozinha de outras pessoas *. | Sinto-me confortável comendo alimentos sem glúten da cozinha de outras pessoas *. | I feel comfortable eating gluten-free food prepared by other people. | Sinto-me confortável comendo alimentos sem glúten da cozinha de outras pessoas. | |

| Being contaminated by gluten in the past has not stopped me from enjoying restaurants *. | Estar contaminado por glúten no passado não me impediu de desfrutar de restaurantes *. | Ser contaminado(a) pelo glúten no passado não me impediu de apreciar restaurantes. | Ser contaminado(a) pelo glúten no passado não me impediu de apreciar restaurantes. | In the past, gluten contamination has not stopped me from enjoying eating in restaurants. | Mesmo já tendo me contaminado com glúten, não deixei de aproveitar a ida a restaurantes | |

| If I ask questions, I can normally find gluten-free food to eat *. | Se eu fizer perguntas, normalmente consigo encontrar alimentos sem glúten para comer *. | Se eu perguntar, eu posso encontrar normalmente comida sem glúten para comer. | Se eu fizer perguntas, normalmente consigo encontrar alimentos sem glúten para comer *. | If I ask around, I can usually find gluten-free food. | Se eu pergunto diretamente aos funcionários do local, geralmente consigo encontrar alimentos sem glúten para comer. | |

| Reverse items with * and add all scores to make total score. | Inverta os itens com * e some todas as pontuações para obter a pontuação total. | Inverta os itens com * e some todas as pontuações para obter a pontuação total. | Inverta os itens com * e some todas as pontuações para obter a pontuação total. | Invert items with * and add all the scores to get the total score. | Inverta os itens com * e some todas as pontuações para obter a pontuação total. |

| CD-FAB-BR (n = 27) | |

|---|---|

| Tests means (SD 1) | 45.07 (12.03) |

| Retest means (SD) | 45.03 (13.57) |

| ICC 2 (95% CI) | 0.928 (0.842–0.967) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, C.d.S.; Nakano, E.Y.; Zandonadi, R.P. Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Testing of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale in Brazil. Nutrients 2026, 18, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010162

Ribeiro CdS, Nakano EY, Zandonadi RP. Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Testing of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale in Brazil. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Camila dos Santos, Eduardo Yoshio Nakano, and Renata Puppin Zandonadi. 2026. "Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Testing of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale in Brazil" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010162

APA StyleRibeiro, C. d. S., Nakano, E. Y., & Zandonadi, R. P. (2026). Cultural Adaptation and Reliability Testing of the Coeliac Disease Food Attitudes and Behaviours Scale in Brazil. Nutrients, 18(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010162