Ultra-Processed Food and Chronic Kidney Disease Risk: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

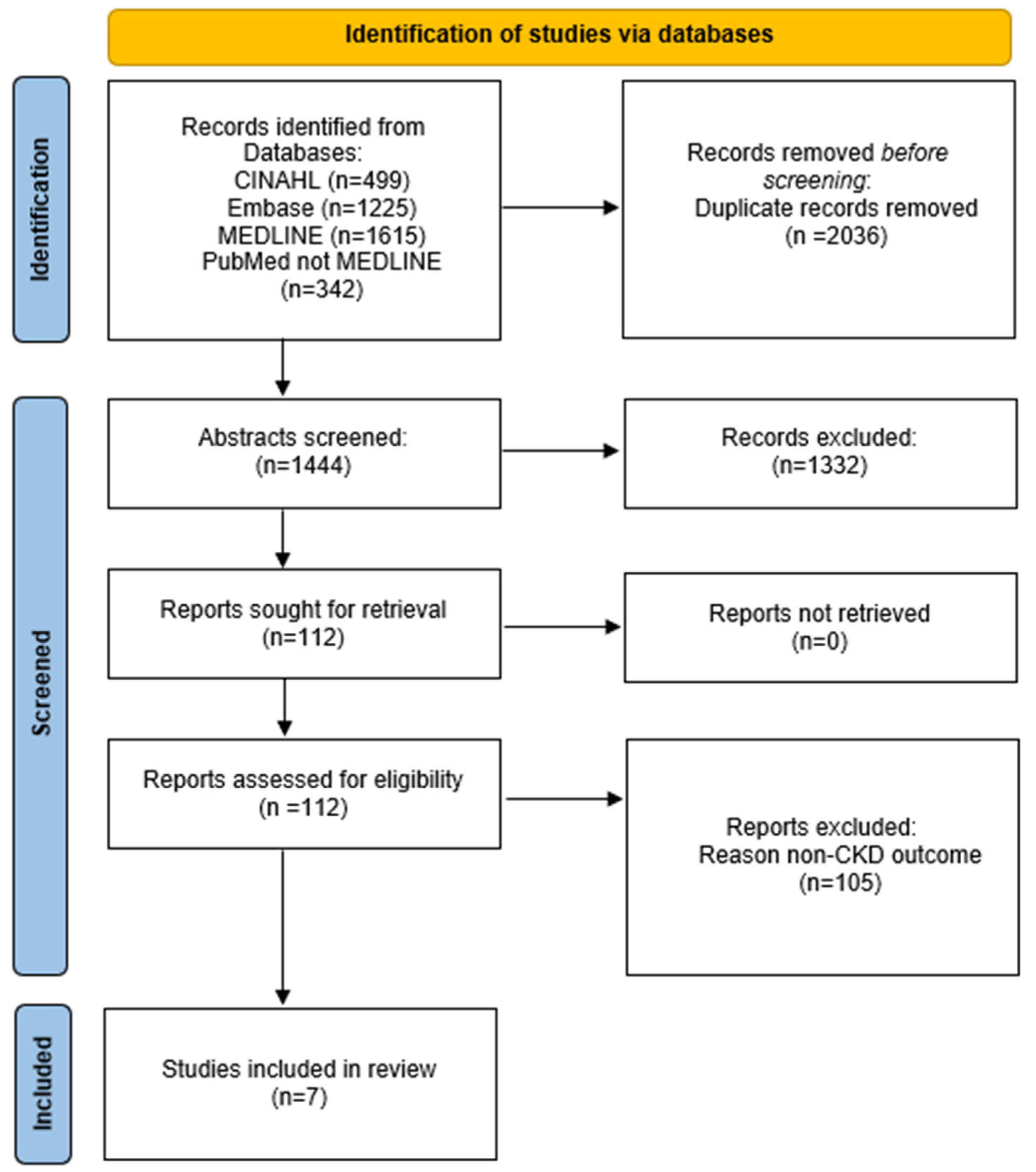

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Register

2.2. Data Sources and Searches

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Exposure Definition

3.3. Outcome Definition

3.4. Risk of Bias

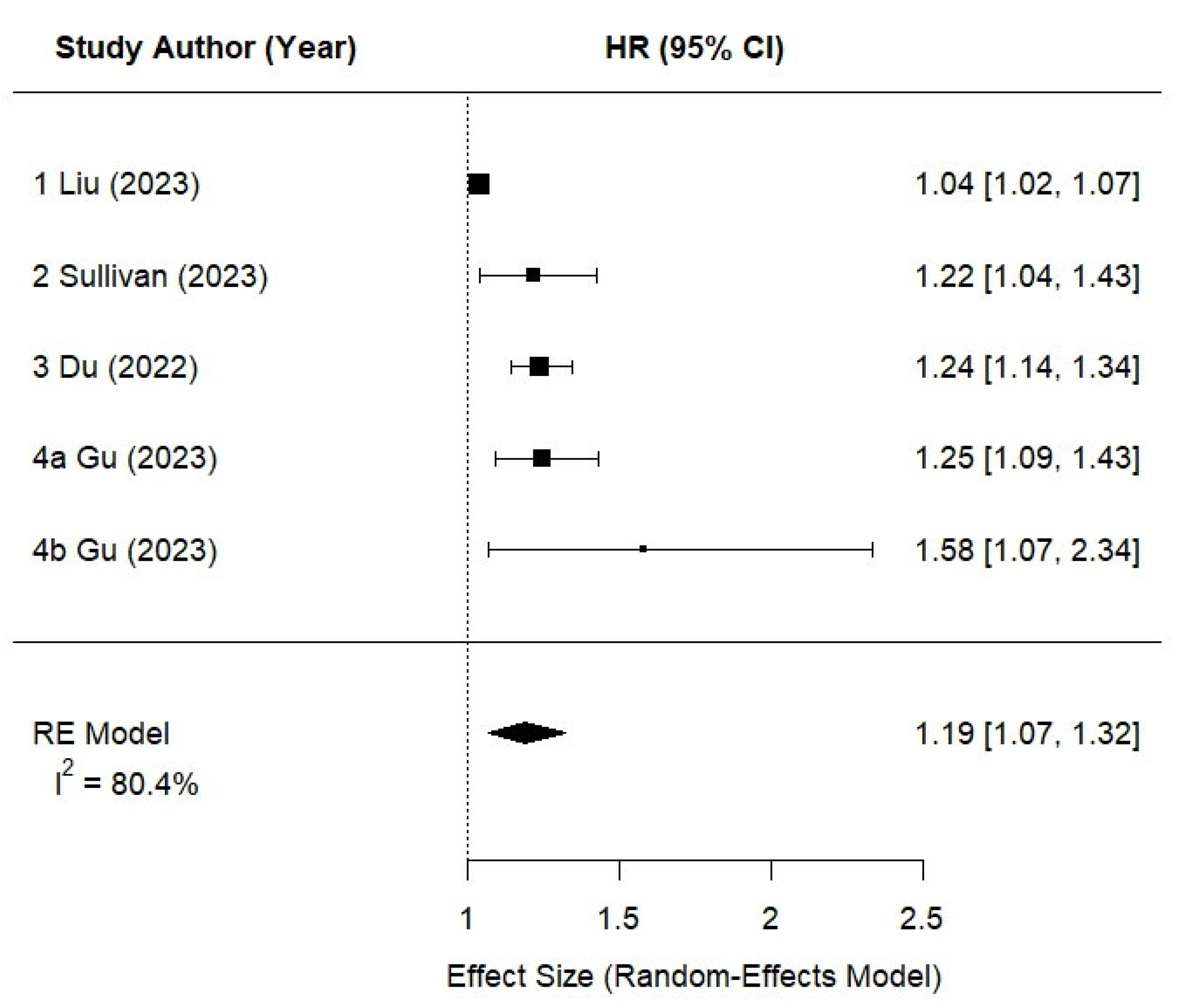

3.5. Meta-Analysis Findings

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. (2011) 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristic, D.; Bender, D.; Jaeger, H.; Heinz, V.; Smetana, S. Towards a definition of food processing: Conceptualization and relevant parameters. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; San-Cristobal, R.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Castaner, O.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gomez, A.M.; Warnberg, J.; et al. Use of Different Food Classification Systems to Assess the Association between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Cardiometabolic Health in an Elderly Population with Metabolic Syndrome (PREDIMED-Plus Cohort). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, M.J.; Forde, C.G.; Mullally, D.; Gibney, E.R. Ultra-processed foods in human health: A critical appraisal. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Steele, E.; Khandpur, N.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Monteiro, C.A. Association between dietary contribution of ultra-processed foods and urinary concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol in a nationally representative sample of the US population aged 6 years and older. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Castro, I.R.; Cannon, G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Puppo, F.; Del Bo, C.; Vinelli, V.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Martini, D. A Systematic Review of Worldwide Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods: Findings and Criticisms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Machado, P.; Santos, T.; Sievert, K.; Backholer, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Huse, O.; Bell, C.; Scrinis, G.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Lin, Y.; Deierlein, A.L.; Vaidean, G.; Parekh, N. Trends in food consumption by degree of processing and diet quality over 17 years: Results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, K.E.; Kelly, J.T.; Palmer, S.C.; Khalesi, S.; Strippoli, G.F.M.; Campbell, K.L. Healthy Dietary Patterns and Incidence of CKD: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews; Eden, J., Levit, L., Berg, A., Morton, S., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avesani, C.M.; Cuppari, L.; Nerbass, F.B.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P. Ultraprocessed foods and chronic kidney disease—Double trouble. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, sfad103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2024.

- Kelly, S.E.; Greene-Finestone, L.S.; Yetley, E.A.; Benkhedda, K.; Brooks, S.P.J.; Wells, G.A.; MacFarlane, A.J. NUQUEST-NUtrition QUality Evaluation Strengthening Tools: Development of tools for the evaluation of risk of bias in nutrition studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, H.; Ajabshir, S.; Alizadeh, S. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension and risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.T.J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3; Updated February 2022; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Rey-García, J.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Bayan-Bravo, A.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption is Associated with Renal Function Decline in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; Duan, M.J.; Dekker, L.H.; Carrero, J.J.; Avesani, C.M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; de Borst, M.H.; Navis, G.J. Ultra-processed food consumption and kidney function decline in a population-based cohort in the Netherlands. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Kim, H.; Crews, D.C.; White, K.; Rebholz, C.M. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Incident CKD: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 589–598.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kityo, A.; Lee, S.-A. The Intake of Ultra-Processed Foods and Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease: The Health Examinees Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, S.; Meng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; et al. Consumption of ultraprocessed food and development of chronic kidney disease: The Tianjin Chronic Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation and Health and UK Biobank Cohort Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, S.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Zhou, C.; Hou, F.F.; Qin, X. Relationship of ultra-processed food consumption and new-onset chronic kidney diseases among participants with or without diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2023, 49, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, V.K.; Appel, L.J.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Tan, T.C.; Brown, J.; Ricardo, A.C.; Schrauben, S.J.; Hsu, C.Y.; Shah, V.O.; Unruh, M.; et al. Changes in Diet Quality, Risk of CKD Progression, and All-Cause Mortality in the CRIC Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 81, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, V.K.; Appel, L.J.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Kim, H.; Unruh, M.L.; Lash, J.P.; Trego, M.; Sondheimer, J.; Dobre, M.; Pradhan, N.; et al. Ultraprocessed Foods and Kidney Disease Progression, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in the CRIC Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 82, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauben, S.J.; Apple, B.J.; Chang, A.R. Modifiable Lifestyle Behaviors and CKD Progression: A Narrative Review. Kidney360 2022, 3, 752–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebholz, C.M.; Young, B.A.; Katz, R.; Tucker, K.L.; Carithers, T.C.; Norwood, A.F.; Correa, A. Patterns of Beverages Consumed and Risk of Incident Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzbashian, E.; Asghari, G.; Mirmiran, P.; Zadeh-Vakili, A.; Azizi, F. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Nephrology 2016, 21, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Chen, J.; Du, S.; Kim, H.; Yu, B.; Wong, K.E.; Boerwinkle, E.; Rebholz, C.M. Metabolomic Markers of Ultra-Processed Food and Incident CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerbass, F.B.; Calice-Silva, V.; Pecoits-Filho, R. Sodium Intake and Blood Pressure in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Salty Relationship. Blood Purif. 2018, 45, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Tan, M.; Ma, Y.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt Reduction to Prevent Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Jules, D.E.; Jagannathan, R.; Gutekunst, L.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Sevick, M.A. Examining the Proportion of Dietary Phosphorus From Plants, Animals, and Food Additives Excreted in Urine. J. Ren. Nutr. 2017, 27, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikizler, T.A.; Burrowes, J.D.; Byham-Gray, L.D.; Campbell, K.L.; Carrero, J.J.; Chan, W.; Fouque, D.; Friedman, A.N.; Ghaddar, S.; Goldstein-Fuchs, D.J.; et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in CKD: 2020 Update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 76, S1–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, L.E.; Hall, K.D.; Herrick, K.A.; Reedy, J.; Chung, S.T.; Stagliano, M.; Courville, A.B.; Sinha, R.; Freedman, N.D.; Hong, H.G.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling of an Ultraprocessed Dietary Pattern in a Domiciled Randomized Controlled Crossover Feeding Trial. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, T.P.; de Moraes, M.M.; Afonso, C.; Santos, C.; Rodrigues, S.S.P. Food Processing: Comparison of Different Food Classification Systems. Nutrients 2022, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiweiss-Sande, R.; Chui, K.; Evans, E.W.; Goldberg, J.; Amin, S.; Sacheck, J. Robustness of Food Processing Classification Systems. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.E.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Subar, A.F.; Reedy, J.; Schap, T.E.; Wilson, M.M.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. The National Cancer Institute’s Dietary Assessment Primer: A Resource for Diet Research. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Grams, M.E.; Crews, D.C.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.J.; Rebholz, C.M. Dietary patterns and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Song, M.; Eliassen, A.H.; Wang, M.; Fung, T.T.; Clinton, S.K.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Tabung, F.K.; et al. Optimal dietary patterns for prevention of chronic disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: An international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Parekh, N.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A.; Chang, V.W. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Giovannucci, E.L. Ultra-processed foods and health: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 10836–10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Titan, S. Measurement and Estimation of GFR for Use in Clinical Practice: Core Curriculum 2021. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 78, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grams, M.E.; Sang, Y.; Ballew, S.H.; Matsushita, K.; Astor, B.C.; Carrero, J.J.; Chang, A.R.; Inker, L.A.; Kenealy, T.; Kovesdy, C.P.; et al. Evaluating Glomerular Filtration Rate Slope as a Surrogate End Point for ESKD in Clinical Trials: An Individual Participant Meta-Analysis of Observational Data. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1746–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamant, M.; Vidal-Petiot, E.; Metzger, M.; Haymann, J.P.; Letavernier, E.; Delatour, V.; Karras, A.; Thervet, E.; Boffa, J.J.; Houillier, P.; et al. Performance of GFR estimating equations in African Europeans: Basis for a lower race-ethnicity factor than in African Americans. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Wang, D.; Sang, Y.; Crews, D.C.; Doria, A.; Estrella, M.M.; Froissart, M.; et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C-Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braden, G.L.; Chapman, A.; Ellison, D.H.; Gadegbeku, C.A.; Gurley, S.B.; Igarashi, P.; Kelepouris, E.; Moxey-Mims, M.M.; Okusa, M.D.; Plumb, T.J.; et al. Advancing Nephrology: Division Leaders Advise ASN. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Neto, A.W.; Osté, M.C.J.; Sotomayor, C.G.; van den Berg, E.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Berger, S.P.; Gans, R.O.B.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Navis, G.J. Mediterranean Style Diet and Kidney Function Loss in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, H.; Schiotz, P.O.; Kruse, A.; Stahl Skov, P. Comparison of intestinal mast cell and basophil histamine release in children with food allergic reactions. Allergy 1989, 44, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osté, M.C.J.; Duan, M.-J.; Gomes-Neto, A.W.; Vinke, P.C.; Carrero, J.-J.; Avesani, C.; Cai, Q.; Dekker, L.H.; Navis, G.J.; Bakker, S.J.L.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and risk of all-cause mortality in renal transplant recipients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1646–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnabel, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Alles, B.; Touvier, M.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Buscail, C.; Julia, C. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Mortality Among Middle-aged Adults in France. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hu, E.A.; Rebholz, C.M. Ultra-processed food intake and mortality in the USA: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994). Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Campà, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Alvarez-Alvarez, I.; Mendonça, R.D.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019, 365, l1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Levin, A. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.; Ansari, S.; Meza, N.; Anderson, A.H.; Srivastava, A.; Waikar, S.; Charleston, J.; Weir, M.R.; Taliercio, J.; Horwitz, E.; et al. Risk Factors for CKD Progression: Overview of Findings from the CRIC Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.M.; Comeau, M.E.; Casperson, S.; Slavin, J.L.; Johnson, G.H.; Messina, M.; Raatz, S.; Scheett, A.J.; Bodensteiner, A.; Palmer, D.G. Dietary Guidelines Meet NOVA: Developing a Menu for A Healthy Dietary Pattern Using Ultra-Processed Foods. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, G.; Ravandi, B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Barabási, A.L. Machine learning prediction of the degree of food processing. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Any study including the following:

| Narrative reviews Systematic reviews Meta-analysis Letters to the editor Conference proceedings Abstracts |

| Study Duration | No restriction | No restriction |

| Sample Size | No restriction | Studies with insufficient reporting outcomes |

| Intervention/Exposure | Ultra-processed food or highly processed | Studies assessing only unprocessed, minimally processed, or other food exposures without UPF focus |

| Comparator | None | None |

| Outcomes | Chronic kidney disease (CKD) incidence, prevalence, and disease progression as measured by change in eGFR | Studies reporting only non-CKD outcomes |

| Date of Publication | After 1 January 2009 | Prior to 1 January 2009 |

| Publication Status | Article published in peer-reviewed journals | Non-peer-reviewed sources, unpublished studies, conference abstracts |

| Language of Publication | English | Languages other than English |

| Country | No restriction | No restriction |

| Study Participants | Human subjects | Studies on non-human subjects, pediatric populations (participants ≤ 19 years old), or exclusively gestational outcomes (e.g., pregnancy-specific kidney outcomes) |

| Age of Study Participants | Adults ≥ 20 years (based on mean/median if available or mid-point of reported age range) | Participants ≤ 19 years (based on mean/median if available or mid-point of reported age range) |

| Publication Details | Sample Description (Size, Age, Length of Follow-Up, Cohort, Location) | Dietary Assessment | Kidney Function | Adjustment | Comparison | OR, RR, or HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Liu et al., 2023 [28] | N = 153,985, age (mean): 55.9 ± 8.0 years, follow-up (median): 12.1 years, UK Biobank, UK | 24 h recall [baseline] | Self-report data and data linkage with primary care, hospital admissions, and death registry records based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) coding system | Adjusted for age, sex, race, Townsend Deprivation Index, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, history of hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, healthy diet score, total energy, c-reactive protein, eGFR, urine albumin/creatinine ratio | T3 vs. T1 | per 10% increment, adjusted HR: 1.04; (1.01; 1.06) [total population] adjusted HR: 1.11; (1.05; 1.17) [with diabetes] adjusted HR: 1.03; (1.00; 1.05) [without diabetes] |

| 2. Sullivan et al., 2023 [30] | N = 2616, age: (mean) 58 ± 11 years, follow-up (median): 7 years, CRIC, USA | FFQ [baseline, 2, 7-year follow-up] | ≥50% decrease in eGFR or initiation of kidney replacement therapy [2021 CKD-EPI equation without race] | Adjusted for age, sex, race, total energy intake, education, income, smoking status, physical activity, study site, eGFR, proteinuria, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, number of blood pressure medications, diabetic status, antiplatelet medication use, lipid-lowering medication, Healthy Eating Index-2015 score | T3 vs. T1 | HR: 1.22 (1.04–1.42) p = 0.01 |

| 3. Du et al., 2022 [25] | N = 14,679, age: 45–64, follow-up (median): 32 (24) years, ARIC Cohort, USA | FFQ [baseline (1987–1989) and visit 3 (1993–1995)] | (1) reduced kidney function (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) accompanied by ≥25% eGFR decline at any follow-up study visit relative to baseline; (2) hospitalization involving CKD stage 3+ diagnosis defined by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9/10 code, identified through active surveillance of the ARIC cohort; (3) death involving CKD stage 3+ diagnosis defined by ICD 9/10 code, identified through linkage to the National Death Index; or (4) end-stage kidney disease defined as dialysis or transplantation, identified by linkage to the USRDS registry | Adjusted for age, sex, race, total energy intake, education level, smoking status, physical activity score | Q4 vs. Q1 | Visit-based definition HR: 1.22, (1.09, 1.37) p trend = 0.009 Composite-based definition HR: 1.19 (1.09, 1.29) p < 0.0001 |

| 4a. Gu et al., 2023 [27] | N = 23,775, age (mean): 33.6–47.5 years, follow-up (median): 4 years, TCLSIH cohort, Tianjin China | FFQ [baseline] | eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, albumin-to-creatinine ratio 30 mg/g, or as having a clinical diagnosis of CKD [MDRD study equation] | Adjusted for age, sex, education level, employment status, household income, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, physical activity, dietary pattern, total energy intake, family history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, other kidney disease, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, albumin, eGFR | Q4 vs. Q1 | HR: 1.58 (1.07, 2.34) p = 0.02 |

| 4b. Gu et al., 2023 [27] | N = 102,332, age (mean): 55–58, follow-up (median): 10.1 years, UK Biobank, UK | 24 h recall [baseline] | eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or as having a clinical diagnosis of CKD, which was ascertained based on information from medical and death records. [MDRD study equation] Incident CKD was ascertained based on information from medical and death records | Adjusted for age, sex, education level, Townsend deprivation index, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, physical activity, healthy dietary score, total energy intake, family history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, other kidney disease, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, eGFR | Q4 vs. Q1 | HR: 1.25 (1.09, 1.43) p < 0.001 |

| 5. Cai et al., 2022 [24] | N = 78,346, age: 45.8 ± 12.6, mean follow-up 3.6 ± 0.9 years, Lifelines Cohort, Netherlands | FFQ [baseline] (2006–2011) | Composite outcome [≥ 30% eGFR decline or incident CKD (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2)] at the second study visit [2009 CKD-EPI equation] | Adjusted for age, sex, baseline eGFR, history of diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease, physical activity, smoking total energy intake, education level, Mediterranean diet score, energy-adjusted protein, carbohydrate and fat intake | Q4 vs. Q1 | OR: 1.27 (1.09–1.47) p = 0.003 Highest quartile had more rapid eGFR decline (β, −0.17; 95% CI, −0.23 to −0.11; p < 0.001) |

| 6. Rey-Garcia et al., 2021 [23] | N = 1312, age: 67 ± 5.5 years, follow-up: 6 years, Seniors-ENRICA-1, Spain | Diet history [baseline] 2008–2010 | SCr increased or an eGFR decreased beyond that expected for age. Change in eGFR beyond that expected for age was calculated in 3 steps: (i) eGFR based on baseline creatinine and age in 2015; (ii) eGFR in 2015 based on both SCr and eGFR in 2015; and (iii) subtracting ii from i [2009 CKD-EPI equation] | Adjusted for age, sex, total energy intake, education level, smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, time spent watching television, total fiber intake, number of chronic conditions, number of medications, history of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, body mass index | T3 vs. T1 | OR: 1.74 (1.14–2.66) p = 0.026 |

| 7. Kityo et al., 2022 [26] | N = 134,544, age (mean): 52 years, follow-up: N/A, HEXA cohort, Korea | FFQ [baseline] | eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [2009 CKD-EPI equation] | Adjusted for age, sex, total energy intake, education level, income, smoking, drinking status, physical activity, body mass index, history of hypertension, high blood sugar, prevalent cardiovascular disease | Q4 vs. Q1 | PR: 1.16 (1.07, 1.25) p = 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonberg, K.E.; Maski, M.R.; Scott, T.M.; Naumova, E.N. Ultra-Processed Food and Chronic Kidney Disease Risk: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Recommendations. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091560

Leonberg KE, Maski MR, Scott TM, Naumova EN. Ultra-Processed Food and Chronic Kidney Disease Risk: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Recommendations. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091560

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonberg, Kristin E., Manish R. Maski, Tammy M. Scott, and Elena N. Naumova. 2025. "Ultra-Processed Food and Chronic Kidney Disease Risk: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Recommendations" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091560

APA StyleLeonberg, K. E., Maski, M. R., Scott, T. M., & Naumova, E. N. (2025). Ultra-Processed Food and Chronic Kidney Disease Risk: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Recommendations. Nutrients, 17(9), 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091560