Consumption of the Food Groups with the Revised Benefits in the New WIC Food Package: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

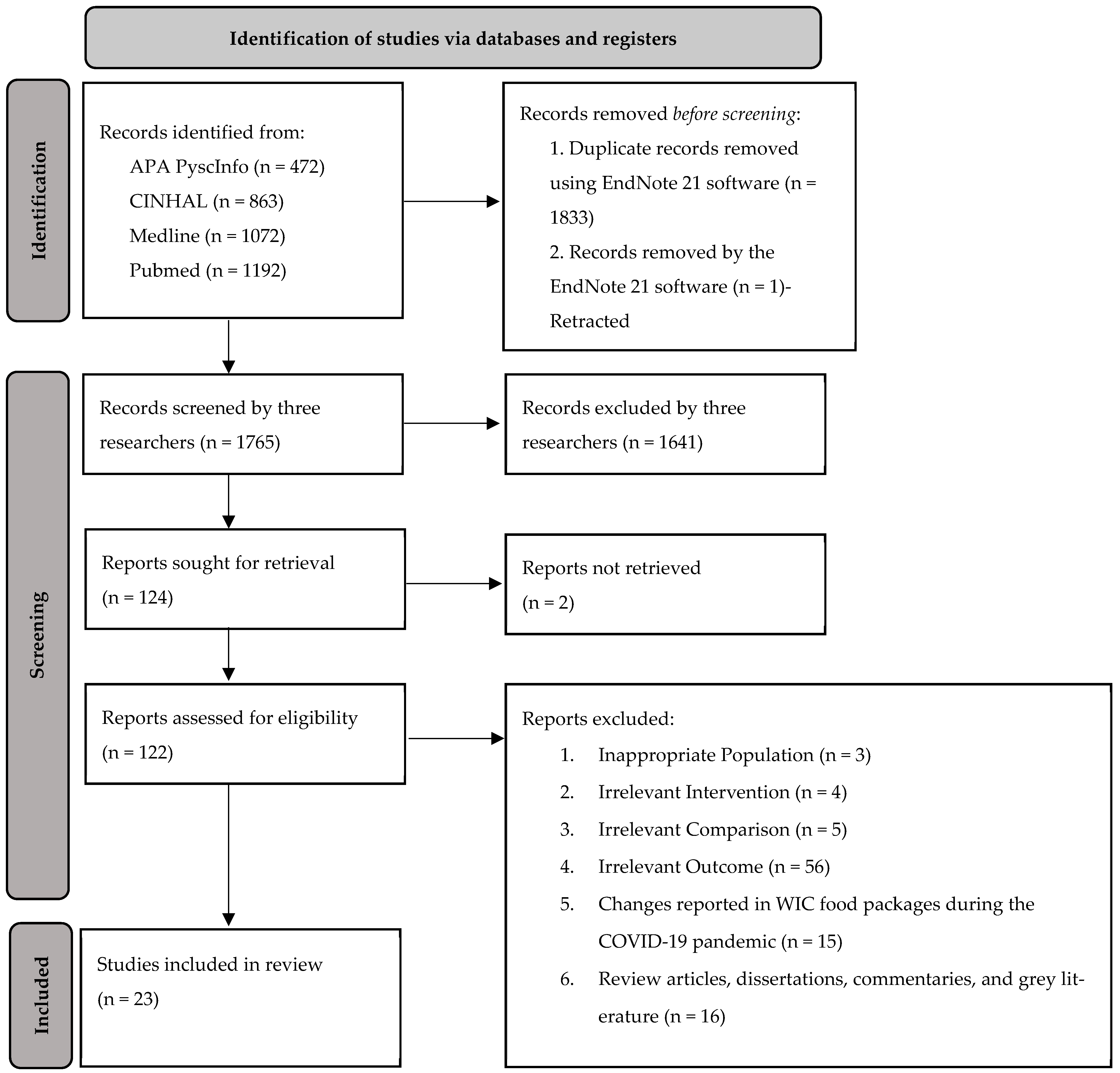

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Fruits and Vegetables

4.2. Infant Fruits and Vegetables

4.3. Juice

4.4. Milk and Dairy Products

4.5. Limitations of the Research Reviewed

4.6. Policy Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Proposed Rule: Revisions in the WIC Food Packages; Food and Nutrition Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/fr-112122 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Final Rule: Revisions in the WIC Food Packages; Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/fr-041824 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Review of WIC Food Packages: Improving Balance and Choice: Final Report; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramani, M.; Ogunwole, S.M.; Caulfield, L.E.; Sharma, R.; Zhang, A.; Gross, S.M.; Hurley, K.M.; Lerman, J.L.; Bass, E.B.; Bennett, W.L. Maternal, infant, and child health outcomes associated with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Alsuliman, M.A.; Wright, M.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X. Fruit and vegetable purchases and consumption among WIC participants after the 2009 WIC food package revision: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D.J.; Byker Shanks, C.; Houghtaling, B. The impact of the 2009 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package revisions on participants: A systematic review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1832–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handu, D.; Moloney, L.; Wolfram, T.; Ziegler, P.; Acosta, A.; Steiber, A. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics methodology for conducting systematic reviews for the evidence analysis library. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.E.; Ritchie, L.D.; Spector, P.; Gomez, J. Revised WIC food package improves diets of WIC families. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, T.; Luedicke, J.; Henderson, K.E.; Tripp, A.S. Grocery store beverage choices by participants in federal food assistance and nutrition programs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, T.; Luedicke, J.; Tripp, A.S.; Henderson, K.E. Effects of reduced juice allowances in food packages for the Women, Infants, and Children program. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiasson, M.A.; Findley, S.E.; Sekhobo, J.P.; Scheinmann, R.; Edmunds, L.; Faly, A.; McLeod, N. Changing WIC changes what children eat. Obesity 2013, 21, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Luedicke, J.; Henderson, K.E.; Schwartz, M.B. The positive effects of the revised milk and cheese allowances in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.L.; Takayama, J.I.; Halpern-Felsher, B.; Badiner, N.; Barker, J.C. Understanding how Latino parents choose beverages to serve to infants and toddlers. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.; Odoms-Young, A.M.; Schiffer, L.A.; Kim, Y.; Berbaum, M.L.; Porter, S.J.; Blumstein, L.B.; Bess, S.L.; Fitzgibbon, M.L. The 18-Month impact of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package revisions on diets of recipient families. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odoms-Young, A.M.; Kong, A.; Schiffer, L.A.; Porter, S.J.; Blumstein, L.; Bess, S.; Berbaum, M.L.; Fitzgibbon, M.L. Evaluating the initial impact of the revised special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food packages on dietary intake and home food availability in African-American and Hispanic families. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, T.; Luedicke, J. Incentivizing fruit and vegetable purchases among participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiqari, L.; Torre, L.; Gazmararian, J.A. Exploring the impact of the new WIC food package on low-fat milk consumption among WIC recipients: A pilot study. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshed, A.B.; Davis, S.M.; Greig, E.A.; Myers, O.B.; Cruz, T.H. Effect of WIC food package changes on dietary intake of preschool children in New Mexico. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2015, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reat, A.M.; Crixell, S.H.; Friedman, B.J.; Von Bank, J.A. Comparison of food intake among infants and toddlers participating in a South Central Texas WIC program reveals some improvements after WIC package changes. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Tripp, A.S. The healthfulness of food and beverage purchases after the federal food package revisions: The case of two New England States. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishdorj, A.; Capps, O., Jr. The impact of policy changes on milk and beverage consumption of Texas WIC children. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2017, 46, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, C.; McLaughlin, P.W.; Diggs, L. Individual and store characteristics associated with brand choices in select food category redemptions among WIC participants in Virginia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, J.F.; Catellier, D.J.; Jacquier, E.F.; Eldridge, A.L.; Johnson, W.L.; Lutes, A.C.; Anater, A.S.; E Quann, E. WIC and non-WIC infants and children differ in usage of some WIC-provided foods. J. Nutr. 2018, 148 (Suppl. 3), 1547S–1556S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.; Hollingsworth, B.A.; Busey, E.A.; Wandell, J.L.; Miles, D.R.; Poti, J.M. Federal nutrition program revisions impact low-income households’ food purchases. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercammen, K.A.; Moran, A.J.; Zatz, L.Y.; Rimm, E.B. 100% juice, fruit, and vegetable intake among children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and nonparticipants. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, e11–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, A.; Huffman, F.G. Beverage intake and its effect on body weight status among WIC preschool-age children. J. Obes. 2019, 2019, 3032457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamner, H.C.; Paolicelli, C.; Casavale, K.O.; Haake, M.; Bartholomew, A. Food and beverage intake from 12 to 23 months by WIC status. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.F.; Anater, A.S.; Hampton, J.C.; Catellier, D.J.; Eldridge, A.L.; Johnson, W.L.; E Quann, E. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children is associated with several changes in nutrient intakes and food consumption patterns of participating infants and young children, 2008 compared with 2016. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Park, K.; Tang, C.; McLaughlin, P.W.; Stacy, B. Women, Infants, and Children cash value benefit redemption choices in the electronic benefit transfer era. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryar, C.D.; Wambogo, E.A.; Scanlon, K.S.; Terry, A.L.; Ogden, C.L. Trends in food consumption among children aged 1–4 years by participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, United States, 2005–2018. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Fulgoni, V.L., III; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Mitmesser, S.H. Dietary intakes of EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids among US childbearing-age and pregnant women: An analysis of NHANES 2001–2014. Nutrients 2018, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Uesugi, K.; Greene, H.; Bess, S.; Reese, L.; Odoms-Young, A. Preferences and perceived value of WIC foods among WIC caregivers. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, J.; Gleason, S.F. Comparison of WIC benefit redemptions in Michigan indicates higher utilization among Arab American families. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46 (Suppl. 3), S45–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.P.; Whaley, S.E.; Gradziel, P.H.; Crocker, N.J.; Ritchie, L.D.; Harrison, G.G. Mothers prefer fresh fruits and vegetables over jarred baby fruits and vegetables in the new Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Interim Final Rule: Revisions in the WIC Food Packages; Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/interim-rule-revisions-wic-food-packages#:~:text=*%20Dec.,1%2C%202010 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Clemens, R.; Drewnowski, A.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Toner, C.D.; Welland, D. Squeezing fact from fiction about 100% fruit juice. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6 (Suppl. 2), 236S–243S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). The 2010 Dietary Guidelines; USDHHS: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/dietary-guidelines/previous-dietary-guidelines/2010 (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). WIC EBT Activities; Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/ebt/activities (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Zaltz, D.A.; Weir, B.W.; Neff, R.A.; Benjamin-Neelon, S.E. Projected impact of replacing juice with whole fruit in early care and education. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 68, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Graves, L.; McGowan, B.; Mayfield, B.J.; Connolly, B.A.; Stevens, W.; Abbott, A. A scoping review of household factors contributing to dietary quality and food security in low-income households with school-age children in the United States. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 914–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, M.M.; Freese, R.; Shults, J.; Stallings, V.A.; Virudachalam, S. Impact of the 2009 WIC food package changes on maternal dietary quality. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Park, K.; Tang, C. App usage associated with full redemption of WIC food benefits: A propensity score approach. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Park, K. The Association of WIC App Usage and WIC Participants’ Redemption Outcomes; Healthy Eating Research: Durham, NC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://healthyeatingresearch.org (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Vasan, A.; Kenyon, C.C.; Feudtner, C.; Fiks, A.G.; Venkataramani, A.S. Association of WIC participation and electronic benefits transfer implementation. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, C.; Park, K.; Harrison, K.; McLaughlin, P.W.; Stacy, B. The role of generic price look-up code in WIC benefit redemptions. J. Public Policy Mark. 2022, 41, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, L.D.; Whaley, S.E.; Spector, P.; Gomez, J.; Crawford, P.B. Favorable impact of nutrition education on California WIC families. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42 (Suppl. 3), S2–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Category | Proposed Changes | Substitution | Final Revisions Based on Public Comment | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juice | Reduced allowance of 100% juice (maximum allowance is 64 oz b/1.89 L) | $3 CVB a | Finalize as proposed | To encourage the consumption of whole forms of fruits and vegetables instead of juice; 100% juice had lower dietary fiber than whole fruits and vegetables. |

| Milk | Reduced by 2 to 4 quarts per month for children; reduced by 6 to 8 quarts per month for pregnant and breastfeeding participants | Lactose-free milk; plain or sweetened yogurt or reduced-fat yogurt; soy-based beverages, yogurt, and cheese; milk-based cheese | Finalize as proposed | 1. To “promote nutrition security and equity. Ensure additional options for participants with special dietary needs and preferences across all State agencies”. 2. To be “consistent with the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) for total sugar allowance”. 3. To allow for “flexibility, variety, and choice” for participants with allergies, lactose intolerance, or a vegan diet. Soy-based beverages are considered part of the dairy group as they have equivalent nutritional content to milk. The rule includes nutrient-minimum specifications for calcium, protein, and vitamin D. |

| Infant Fruits and Vegetables | Reduced allowance (from 256 oz/7.57 L to 128/3.78 L oz per month for both fully breastfed and partially breastfed/fully formula-fed infants) | $10 (64 oz/1.89 L) or $20 CVV c (full 128 oz/3.78 L) | Finalize as proposed | To bring the amount of infant fruits and vegetables allowed to an appropriate level for daily consumption for infants (6–11 months). |

| Canned Fish | Reduced the amount of canned fish to fully breastfeeding participants from 30 oz/850 g to 20 oz/567 g | Legumes and peanut butter at 3 month-rotations | Finalize as proposed | To maintain cost neutrality. |

| Concept | Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Keyword(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Food assistance | Women infants and children; WIC; special supplement * nutrition program for women, infants, and children; food program |

| Food packaging | Food package * | |

| 2 | Consumer behavior | Allowance * |

| Food security | Food intake | |

| Food preferences | Food consumption/consum * | |

| Diet, food, and nutrition | Redeem | |

| Child nutritional physiological phenomena | Redemption, purchase | |

| Feeding behavior | Choice | |

| Choice behavior | Dietary practice | |

| Diet, food, and nutrition | Nutrition program | |

| Recommended dietary allowances | Eating habit *, benefit, diet *, nutrition * | |

| 3 | Mothers | Child * |

| Female | Baby/babies | |

| Child, Preschool | Women/woman/female */mother * |

| Author(s) | Year | Setting/Location | Food Category | Outcome | Result Summary | Quality * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whaley et al. [9] | 2012 | California | F&V b | Consumption | Fruit and vegetable consumption increased from 2009 to 2010. | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | Whole milk consumption decreased in caregivers and children, while low-fat milk consumption increased from 2009 to 2010. | ||||

| Andreyeva et al. [10] | 2012 | New England States | Juice | Redemption | WIC-only households purchased more 100% fruit juice beverages (by volume) than WIC households receiving SNAP c benefits. | Positive |

| Andreyeva et al. [11] | 2013 | New England States | Juice | Redemption | Total purchases of 100% juice decreased by 23.5% from 2009 to 2010. | Positive |

| Chiasson et al. [12] | 2013 | New York State | Milk | Consumption | Whole milk consumption decreased, while low-fat milk consumption increased in 2011 compared to 2008 among WIC children aged 2–4 y e. | Positive |

| F&V | Consumption | Daily fruit and vegetable intake increased among WIC children aged 1–4 y. | ||||

| Andreyeva et al. [13] | 2014 | New England States | Milk | Redemption | Whole milk redemption decreased substantially among WIC households from 2009 to 2010. | Positive |

| Cheese | Redemption | Substantial decrease in WIC-eligible cheese purchases. | ||||

| Beck et al. [14] | 2014 | California | Juice | Consumption | WIC caregivers were confused about why WIC provides juice yet counseled parents to avoid giving children juice. | Neutral |

| Kong et al. [15] | 2014 | Chicago | Milk | Consumption | Consumption of reduced-fat milk significantly increased for African American and Hispanic children and mothers; whole milk intake significantly decreased for all groups. | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | Consumption of fruit juice was reduced among Hispanic mothers. | ||||

| F&V | Consumption | No significant change in fruit and vegetable consumption from 2009 to 2011 in the WIC mother–child dyads. | ||||

| Odoms-Young et al. [16] | 2014 | Chicago | F&V | Consumption | Consumption of fruit increased among Hispanic mothers from 2009 to 2010. No changes in the consumption of vegetables among WIC mothers and children. | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | Consumption of low-fat dairy products increased among Hispanic mothers and children and African American children. | ||||

| Juice | Consumption | Consumption reduced in Hispanic mothers but no significant change in Hispanics or African American children or African American mothers. | ||||

| Andreyeva and Luedicke [17] | 2015 | New England States | F&V | Redemption | Increase in purchases of fresh fruits and both fresh and frozen vegetables from 2009 to 2010 among WIC households. Three times more spent purchasing fresh fruits than fresh vegetables. | Positive |

| Meiqari et al. [18] | 2015 | Atlanta | Milk | Consumption | Consumption of low-fat milk among WIC children significantly increased one to four weeks after the implementation but no significant change in WIC mothers’ consumption. | Positive |

| Morshed et al. [19] | 2015 | New Mexico | F&V | Consumption | Consumption of vegetables, excluding potatoes, decreased from 2008 to 2010 among preschool children in WIC households, while fruit consumption remained unchanged. | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | Consumption of lower-fat milk significantly increased. | ||||

| Juice | Consumption | No significant change in the consumption of fruit juice. | ||||

| Reat et al. [20] | 2015 | Texas | F&V | Consumption | No observed change in fruit and vegetable consumption among WIC toddlers (1–2 y) between 2009 and 2011. | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | No significant change in juice consumption among WIC infants (6–12 m f) and toddlers (1–2 y). | ||||

| Infant F&V | Consumption | No significant change observed in the consumption of infant fruits and vegetables among WIC infants (6–12 m). | ||||

| Andreyeva et al. [21] | 2016 | New England States | Milk | Redemption | Decreased volume of whole milk purchased from 2009 to 2010 among WIC households. | Positive |

| Juice | Redemption | Decreased volume of 100% juice purchased. | ||||

| Ishdorj and Capps [22] | 2017 | Texas | Milk | Consumption | Significant decrease in the consumption of whole milk among WIC children from 2008–2009 to 2010–2011, with an increase in the amount of lower-fat milk consumed. | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | The frequency of consumption of 100% juice increased. | ||||

| Zhang et al. [23] | 2017 | Virginia | Infant F&V | Redemption | Minority participants redeemed higher-priced brands of infant fruits and vegetables. | Positive |

| Guthrie et al. [24] | 2018 | National | F&V | Consumption | Among 12–23.9 m olds, fewer WIC children consumed fruit compared to both lower- and higher-income nonparticipants. No difference in the consumption of vegetables (higher-income 12–47.9 m). | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | Compared to non-WIC children, WIC children aged 12–23.9 m drank more whole milk, while children aged 24–47.9 m drank more low-fat and non-fat milk. | ||||

| Juice | Consumption | WIC infants and children were more likely to consume 100% juice compared to non-WIC. | ||||

| Infant F&V | Consumption | WIC 6- to 11.9-mo-olds were more likely to consume infant vegetables than lower-income nonparticipants. No difference was observed in fruit consumption. | ||||

| Cheese | Consumption | No significant difference was observed in cheese consumption among WIC children and lower-income nonparticipants. | ||||

| Ng et al. [25] | 2018 | National | F&V | Redemption | Increased purchases of fruits and vegetables from 2008 to 2014 among WIC households with preschoolers. | Positive |

| Milk | Redemption | Decreased purchases of high-fat milk. | ||||

| Juice | Redemption | Decreased purchases of 100% juice. | ||||

| Vercammen et al. [26] | 2018 | National | F&V | Consumption | No difference in consumption of whole fruit and total vegetables between WIC children (2–4 y) and non-WIC children. | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | WIC children consumed significantly more 100% fruit juice than nonparticipants, exceeding the age-specific American Academy of Pediatrics maximum intake for juice. | ||||

| Charvet et al. [27] | 2019 | Florida | Milk | Consumption | No significant difference in the consumption of milk between non-Hispanic black and Hispanic WIC children (3–4.9 y). | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | WIC children consumed over twice the recommended amount of 100% fruit juice daily. Non-Hispanic Black children consumed more 100% fruit juice than Hispanic children. | ||||

| Hamner et al. [28] | 2019 | National | F&V | Consumption | WIC children (12–23 m) consumed more fruits and vegetables, excluding white potatoes, than non-WIC children. | Positive |

| Juice | Consumption | WIC children consumed more 100% fruit juice than non-WIC children. | ||||

| Milk | Consumption | No significant differences in consumption of whole, reduced-fat, low-fat, nonfat, or total milk by WIC participation status. | ||||

| Guthrie et al. [29] | 2020 | National | F&V | Consumption | WIC children (12–47.9 m) consumed more fruits and vegetables in 2016 compared to 2008. | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | A greater percentage of WIC children (12–47.9 m) consumed whole milk from 2008 to 2016, and a smaller percentage of WIC children (12–47.9 m) consumed reduced-fat milk. However, a greater percentage of WIC children (24–47.9 m) consumed more low-fat milk compared from 2008 to 2016. | ||||

| Juice | Consumption | A smaller percentage of WIC children (12–23.9 m) consumed 100% fruit juice from 2008 to 2016. No significant change in the 100% fruit juice consumption in WIC infants and children (24–47.9 m). | ||||

| Infant F&V | Consumption | WIC infants consumed more infant fruits and vegetables in 2016 compared to 2008. | ||||

| Cheese | Consumption | A greater percentage of WIC children consumed cheese in 2016 than in 2008, with no statistical significance. | ||||

| Zhang et al. [30] | 2022 | Virginia | F&V | Redemption | Fresh fruits and vegetables accounted for 77.3% of CVB d redemptions. Non-Hispanic white and Black WIC households redeemed a smaller share of CVB than Hispanic households. | Positive |

| Fryar et al. [31] | 2023 | National | F&V | Consumption | The percentage of WIC children (1–4 y) who consumed whole fruit significantly increased from 2005–2006 to 2017–2018. No significant change in vegetable consumption. | Positive |

| Milk | Consumption | WIC children had a significant increase in low-fat and non-fat milk consumption. But a lower percentage of WIC children consumed whole milk from 2005–2006 to 2017–2018. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Patel, P.T.; Neupane, B.; Lowery, C.M.; Alkhalifah, F.; Mahdavi, F.; Sarino, E.M. Consumption of the Food Groups with the Revised Benefits in the New WIC Food Package: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050856

Zhang Q, Patel PT, Neupane B, Lowery CM, Alkhalifah F, Mahdavi F, Sarino EM. Consumption of the Food Groups with the Revised Benefits in the New WIC Food Package: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(5):856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050856

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qi, Priyanka T. Patel, Bidusha Neupane, Caitlin M. Lowery, Futun Alkhalifah, Faezeh Mahdavi, and Esther May Sarino. 2025. "Consumption of the Food Groups with the Revised Benefits in the New WIC Food Package: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 17, no. 5: 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050856

APA StyleZhang, Q., Patel, P. T., Neupane, B., Lowery, C. M., Alkhalifah, F., Mahdavi, F., & Sarino, E. M. (2025). Consumption of the Food Groups with the Revised Benefits in the New WIC Food Package: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 17(5), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050856