Efficacy and Safety of Placental Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualification Standards

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. PICO Criteria

- P—Menopausal women;I—Placental extract treatment;C—Placebo or sham treatment;O—Change in menopausal symptom severity and safety profile.

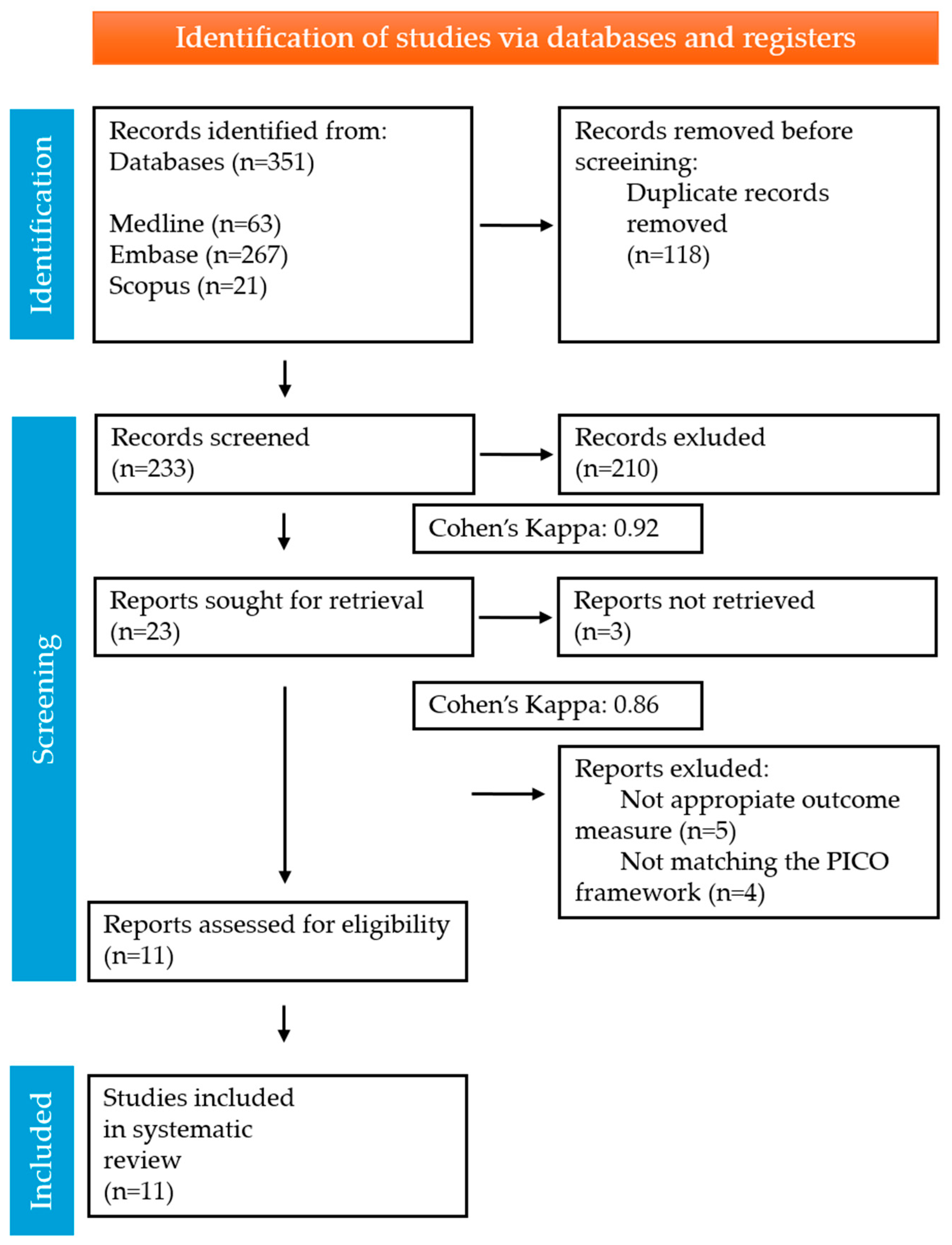

2.4. Data Selection

2.5. Selection of Title and Abstract

2.6. Selection of Full Text

2.7. Procedure for Gathering Data

2.8. Assessment of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Basic Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Primary Outcomes

3.3.1. Menopausal Severity Scores

Kupperman Menopausal Index

Simplified Menopausal Index

Menopause Rating Scale

3.3.2. Somatic Symptoms

3.3.3. Vasomotor Symptoms

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

3.4.1. Aesthetics

3.4.2. Psychological Symptoms

3.5. Hormonal Changes and Cardiovascular Effects

3.6. Adverse Events, Side Effects

4. Discussion

- Strengths and Limitations

- Implications for Practice

- Implications for Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRS | Menopause Rating Scale |

| GCS | Greene Climacteric Scale |

| KMI | Kupperman Index |

| SMI | Simplified Menopausal Index |

| HRT | Hormone Replacement Therapy |

| pMSCs | Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| FSS | Fatigue Severity Scale |

| HFS | Hot Flash Score |

| ZSDS | Zung ’s Self-Rating Depression Scale |

| STAI | Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory |

References

- Nelson, H.D. Menopause. Lancet 2008, 371, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaulikar, V. Menopause transition: Physiology and symptoms. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 81, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, C.; Simpson, P. Menopause: Physiology, definitions, and symptoms. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 38, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, K.; Ruebig, A.; Potthoff, P.; Schneider, H.P.; Strelow, F.; Heinemann, L.A.; Do, M.T. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) scale: A methodological review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, C.; O’Neill, S.M.; King, R.; Battistutta, D.; Khoo, S.K. Greene Climacteric Scale: Norms in an Australian population in relation to age and menopausal status. Climacteric 2005, 8, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaplaine, R.W.; Bottomy, J.R.; Blatt, M.; Wiesbader, H.; Kupperman, H.S. Effective control of the surgical menopause by estradiol pellet implantation at the time of surgery. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1952, 94, 323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.T.; Kotani, K. An inverse relation between the Simplified Menopausal Index and biological antioxidant potential. Climacteric 2013, 16, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Manabe, A.; Okada, M.; Kurioka, H.; Kanasaki, H.; Miyazaki, K. Efficacy and safety of oral estriol for managing postmenopausal symptoms. Maturitas 2000, 34, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneswaran, K.; Hamoda, H. Hormone replacement therapy—Current recommendations. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 81, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwam, C.; Ohanele, C.; Hamby, J.; Chughtai, N.; Mufti, Z.; Ma, X. Human placental extract: A potential therapeutic in treating osteoarthritis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, J.J.; Sakoda, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hisamichi, K.; Kaku, T.; Tamada, K. Preventive and therapeutic potential of placental extract in contact hypersensitivity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Park, D.S.; Jang, J.Y.; Lee, I.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, G.S.; Oh, C.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, H.J.; Han, B.S.; et al. Human Placenta Hydrolysate Promotes Liver Regeneration via Activation of the Cytokine/Growth Factor-Mediated Pathway and Anti-oxidative Effect. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh Soltani, S.; Forogh, B.; Ahmadbeigi, N.; Hadizadeh Kharazi, H.; Fallahzadeh, K.; Kashani, L.; Karami, M.; Kheyrollah, Y.; Vasei, M. Safety and efficacy of allogenic placental mesenchymal stem cells for treating knee osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, D.H.; Na, J.; Im, S.I.; Oh, C.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.K.; Han, H.J.; Seok, J.; Choi, S.Y.; Ko, E.J.; et al. Antioxidant effect of human placenta hydrolysate against oxidative stress on muscle atrophy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagae, M.; Nagata, M.; Teramoto, M.; Yamakawa, M.; Matsuki, T.; Ohnuki, K.; Shimizu, K. Effect of Porcine Placenta Extract Supplement on Skin Condition in Healthy Adult Women: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.K.; Choi, W.S.; Yum, K.S.; Song, S.W.; Ock, S.M.; Park, S.B.; Kim, M.J. Efficacy and safety of human placental extract solution on fatigue: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 130875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, D.H.; Na, J.; Choi, M.J.; Lee, B.C.; Oh, C.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, B.J. Anti-apoptotic effects of human placental hydrolysate against hepatocyte toxicity in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2569–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purevdorj, T.; Arata, M.; Nii, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Noguchi, H.; Takeda, A.; Aoki, H.; Inui, H.; Kagawa, T.; Kinouchi, R.; et al. Porcine Placental Extract Improves the Lipid Profile and Body Weight in a Post-Menopausal Rat Model Without Affecting Reproductive Tissues. Nutrients 2025, 17, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Chung, H.H.; Kang, S.B. Efficacy and safety of human placenta extract in alleviating climacteric symptoms: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Res. 2009, 35, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, C.; Yoon, S.H.; Choi, H. Effect of porcine placental extract on menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Ahn, K.-H.; Park, H.-T.; Song, J.-Y.; Hong, S.-C.; Kim, T. A Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Parallel, Non-Inferiority Clinical Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Unicenta and Melsmon for Menopausal Symptom Improvement. Medicina 2023, 59, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanohara, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Masunaga, S.; Ohishi, M.; Komatsu, Y.; Nagase, M. Effect of porcine placental extract on the mild menopausal symptoms of climacteric women. Climacteric 2017, 20, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Yamazaki, R.; Yoshikawa, C.; Takano, F.; Takuma, K.; Sugiura, K.; Inoue, M. Efficacy of porcine placental extract on climacteric symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2013, 16, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.-H.; Lee, E.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Cho, S.-J.; Hong, Y.-S.; Park, S.-B. Effect of human placental extract on menopausal symptoms, fatigue, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged Korean women. Menopause 2008, 15, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Kim, D.I.; Yoon, S.H.; Choi, C.M.; Yoo, J.E. Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial on Hominis placenta extract pharmacopuncture for hot flashes in peri- and post-menopausal women. Integr. Med. Res. 2022, 11, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Yamazaki, R.; Yoshikawa, C.; Takano, F.; Sugiura, K.; Inoue, M. Efficacy of porcine placental extract on shoulder stiffness in climacteric women. Climacteric 2013, 16, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Yamazaki, R.; Yoshikawa, C.; Takuma, K.; Sugiura, K.; Inoue, M. Efficacy of porcine placental extracts with hormone therapy for postmenopausal women with knee pain. Climacteric 2012, 15, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, C.; Koike, K.; Takano, F.; Sugiur, K.; Suzuki, N. Efficacy of porcine placental extract on wrinkle widths below the eye in climacteric women. Climacteric 2014, 17, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, M.A.; Erbil, N. The effect of menopausal symptoms on women’s daily life activities. Menopausal Rev. 2023, 22, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xie, Z.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, M.; Wu, J.; Shu, K.; Shi, H.; Xie, M.; Lv, S.; et al. Changes in menopausal symptoms comparing oral estradiol versus transdermal estradiol. Climacteric 2024, 27, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.L.; Lee, H.K.; Chon, H.S.; Pae, H.O.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, Y.I.; Kim, S. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Fermented Soybean-Lettuce Powder for Improving Menopausal Symptoms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, D.; Sugawara, T.; Hirota, T.; Nakamura, Y. Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 on Mild Menopausal Symptoms in Middle-Aged Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Cabre, H.E.; Eckerson, J.M.; Candow, D.G. Creatine Supplementation in Women’s Health: A Lifespan Perspective. Nutrients 2021, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, M.L.; Oliveira, M.N.; Vieira-Potter, V.J. Adipocyte Metabolism and Health after the Menopause: The Role of Exercise. Nutrients 2023, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupperman, H.S.; Blatt, M.H.G.; Wiesbader, H.; Filler, W. Comparative clinical evaluation of estrogenic preparations by the menopausal and amenorrheal indices. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1953, 13, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canário, A.C.G.; Cabral, P.U.; Spyrides, M.H.; Giraldo, P.C.; Eleutério, J.; Gonçalves, A.K. The impact of physical activity on menopausal symptoms in middle-aged women. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 118, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Men, K. The relationship between physical activity and the severity of menopausal symptoms: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; Kagawa, S.; Saito, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Tsuyuguchi, M.J.M.T. Clinical treatment test of Melsmon on menopausal disorder. Medicat. Treat 1981, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, T. Menopausal index. Obs. Gynecol. Ther. 1998, 76, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, Y.; Nagamatsu, T.; Kitabatake, Y.; Sensui, H. Effects of stretching on menopausal and depressive symptoms in middle-aged women: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2016, 23, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţiţ, D.M.; Pallag, A.; Iovan, C.; Furău, G.; Furău, C.; Bungău, S. Somatic-vegetative Symptoms Evolution in Postmenopausal Women Treated with Phytoestrogens and Hormone Replacement Therapy. Iran J. Public Health 2017, 46, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Tan, S.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hong, Z. The effect of diet and exercise on climacteric symptomatology. Asia Pac J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 31, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodis, H.N.; Mack, W.J.; Henderson, V.W.; Shoupe, D.; Budoff, M.J.; Hwang-Levine, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, M.; Dustin, L.; Kono, N.; et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, E. The Blatt-Kupperman menopausal index: A critique. Maturitas 1998, 29, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Study Design | Number of Patients | Dose of Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Study | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2009) [20] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 108 | 100 mg human placental extract 3 times/week s.c. | 4 weeks | KMI score, vasomotor symptoms |

| Lee et al. (2020) [21] | Multicenter, Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 100 | 400 mg porcine placental extract p.o./day | 12 weeks | KMI score |

| Kim et al. (2023) [22] | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel, non-inferiority clinical study | 141 | 2 mL human placenta extract subcutaneous injection 3 times/week | 12 days | KMI score, hormonal changes, vasomotor symptoms |

| Kitanohara et al. (2017) [23] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | 50 | 300 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | SMI score, serum estradiol, follicle stimulating hormone, vasomotor, psychological and somatic symptoms |

| Koike et al. (2013) [24] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 76 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | SMI score, Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale, the Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, vasomotor symptoms |

| Nagae et al. (2020) [15] | Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study | 20 | 200 mg porcine placenta extract/day p.o. | 4 weeks | SMI score, skin quality parameters |

| Kong et al. (2008) [25] | Randomized, controlled trial | 84 | First 2 weeks: 4 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; second 2 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; last 4 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract once a week (total 32 mL) | 8 weeks | Menopausal Rating Scale (MRS), Fatigue Severity Scale, Visual Analog Scale to assess the degree of fatigue, 17 beta-estradiol level |

| Choi et al. (2022) [26] | Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 128 | 2 mL human placental extract subcutaneous injection twice weekly | 9 weeks | Hot flash score, the Menopausal Rating Scale, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, and estradiol (E2) levels |

| Koike et al. (2013) [27] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 66 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | Shoulder stiffness by the Visual Analog Scale |

| Koike et al. (2012) [28] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 48 | 3150 mg porcine placental extract daily p.o. with hormone replacement therapy or estrogen-alone therapy | 12 weeks | Knee pain by the Visual Analog Scale |

| Yoshikawa et al. (2014) [29] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study and retrospective comparison | 167 | Group 1: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; Group 2: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | Wrinkle widths |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | KMI Score Before and After Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2009) [20] | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 108 | 100 mg human placental extract subcutaneous injection 3 times/week | 4 weeks | 36/24 | The degree of decrease in the KMI score was significantly greater in the human placental extract group than in the placebo group (−12.30 ± 10.44 vs. −7.15 ± 9.11, p = 0.012) after 4 weeks of treatment |

| Lee et al. (2020) [21] | Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial | 100 | 400 mg porcine placental extract per os | 12 weeks | 35/17–18 | KMI significantly decreased after 12 weeks in patients whose BMI was 23 kg/m2 or above and in early menopausal women compared to the placebo group |

| Kim et al. (2023) [22] | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel, non-inferiority clinical trial | 141 | 2 mL human placenta extract subcutaneous injection 3 times/week | 12 days | 31/16 | The effects of the two human placenta extracts do not differ significantly in terms of KMI |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | SMI Score Before and After Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kitanohara et al. (2017) [23] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | 150 | 300 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | 36/22 | After 12 weeks, the porcine placental extract group’s overall SMI score had improved significantly more than the placebo group’s (p = 0.031). The porcine placental extract group’s vasomotor, psychological, and somatic symptoms considerably improved after 12 weeks (p < 0.05). |

| Koike et al. (2013) [24] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 76 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | 50/21 | SMI significantly decreased after 24 weeks compared to the control group. |

| Nagae et al. (2020) [15] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 20 | 200 mg porcine placenta extract/day p.o. | 4 weeks | 50/40 | Skin barrier function (transepidermal water loss) significantly decreased after 4 weeks of porcine placental extract treatment. No significant difference was found in the SMI score compared to the placebo group. |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koike et al. (2013) [27] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 66 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | Six capsules of porcine placental extract per day was significantly effective in reducing the Visual Analog Scale |

| Koike et al. (2012) [28] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 48 | 3150 mg porcine placental extract daiy p.o. with hormone replacement therapy or estrogen-alone therapy | 12 weeks | Treatment with porcine placental extract was significantly effective in reducing the VAS score for knee pain |

| Kitanohara et al. (2017) [23] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | 50 | 300 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | The porcine placental extract group’s vasomotor, psychological, and somatic symptoms considerably improved at 12 weeks (p < 0.05) |

| Koike et al. (2013) [24] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 76 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | Reductions in the subscale scores of SMI for joint pain: at 24 weeks and at 28 weeks (4 weeks after therapy) |

| Kong et al. (2008) [25] | Randomized, controlled trial | 84 | First 2 weeks: 4 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; second 2 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; last 4 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract once a week (total 32 mL) | 8 weeks | Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) score at the end of the study period was significantly decreased from baseline; the mean total Menopause Rating Scale score of the human placental extract group at 8 weeks was significantly lower than that of the placebo group; the mean total Menopause Rating Scale and three subscale scores in the two groups at the end of the study period were significantly lower than the scores at baseline; Visual Analog Scale score in the human placental extract group was significantly decreased at the end 8 weeks |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al. (2022) [26] | Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 128 | 2 mL human placental extract subcutaneous injection twice weekly | 9 weeks | Hot flash score decreased significantly at 9 weeks. One month after 9 weeks, the score of the placental extract group was reduced, but the score increased in the control group. |

| Kim et al. (2023) [22] | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel, non-inferiority, clinical study | 141 | 2 mL human placenta extract subcutaneous injection 3 times/week | 12 days | Both placental extract groups (Melsmon and Unicenta) showed statistically significant improvements in the frequency of daytime hot flashes, frequency of nighttime hot flashes, total score of daytime hot flashes, and score of nighttime hot flashes. There were no statistically significant differences in the evaluation of facial flashes. |

| Kitanohara et al. (2017) [23] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | 50 | 300 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | The porcine placental extract group’s vasomotor, psychological, and somatic symptoms considerably improved at 12 weeks (p < 0.05). |

| Koike et al. (2013) [24] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 76 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | Reductions in the subscale scores of SMI for joint pain: 63.3% at 24 weeks, 58.3% at 28 weeks (4 weeks after therapy). Significantly effective in reducing hot flashes, insomnia, irritability, depression, fatigue, and joint pain at 12 weeks (p < 0.01) and 24 weeks (p< 0.01). |

| Lee et al. (2009) [20] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 108 | 100 mg human placental extract 3 times/week s.c. | 4 weeks | Vasomotor troubles significantly decreased at 4 weeks. |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoshikawa et al. [29] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study and retrospective comparison | 167 | Group 1.: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; Group 2.: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | 12 weeks of porcine placental extract treatment caused a significant reduction in wrinkle widths below the eye in subjects treated with three capsules of porcine placental extact per day (p < 0.05), as well as in subjects treated with six capsules of porcine placenal extract per day (p < 0.01) compared with untreated subjects. Treatment with three capsules of porcine placental extract per day was significantly effective in reducing the wrinkle widths below the eye both at 12 weeks (p < 0.05) and 24 weeks (p < 0.01) compared with the baseline. |

| Nagae et al. (2020) [15] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 20 | 200 mg porcine placenta extract/day p.o. | 4 weeks | Simplified Menopausal Index over 4 weeks showed a trend toward higher values in the test group than in the placebo group, which did not reach significance (p = 0.079). Arm skin transepidermal water loss was observed, with a significant difference for 4 weeks. Arm skin elasticity was significantly greater in the test group than in the placebo group (p = 0.017). |

| Author (Year) | Study Type | Number of Patients | Porcine/Human Placental Extract | Duration of Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kong et al. (2008) [25] | Randomized, controlled trial | 84 | First 2 weeks: 4 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; second 2 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract 2 times/week s.c.; last 4 weeks: 2 mL human placental extract once a week (total 32 mL) | 8 weeks | Fatigue Severity Scale score (3.2 ± 1.4) at the end of the study period was significantly decreased from baseline |

| Kitanohara et al. (2017) [23] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study | 50 | 300 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 12 weeks | The porcine placental extract group’s vasomotor, psychological, and somatic symptoms considerably improved at 12 weeks (p < 0.05) |

| Koike et al. (2013) [24] | Open-label, randomized, controlled study | 76 | First 12 weeks: 1050 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o.; second 12 weeks: 2100 mg porcine placental extract/day p.o. | 24 weeks | Significantly effective in reducing the total SMI, ZSDS, STAI-1, and STAI-2 scores at week 12 and week 24; significantly effective in reducing hot flashes, insomnia, irritability, depression, fatigue, and joint pain at 12 weeks and 24 weeks; reductions in the subscale scores of SMI for irritability, depression: 75.3%, 61.2% at 24 weeks, 60.3%, 51.2% at 28 weeks (4 weeks after therapy); insomnia subscale score reduction: 74.7% at 24 weeks, 57.9% at 28 weeks (4 weeks after therapy) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papp, S.; Tűű, L.; Nas, K.; Telkes, Z.; Keszthelyi, L.; Keszthelyi, M.; Ács, N.; Várbíró, S.; Török, M. Efficacy and Safety of Placental Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243857

Papp S, Tűű L, Nas K, Telkes Z, Keszthelyi L, Keszthelyi M, Ács N, Várbíró S, Török M. Efficacy and Safety of Placental Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243857

Chicago/Turabian StylePapp, Sára, László Tűű, Katalin Nas, Zsófia Telkes, Lotti Keszthelyi, Márton Keszthelyi, Nándor Ács, Szabolcs Várbíró, and Marianna Török. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety of Placental Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243857

APA StylePapp, S., Tűű, L., Nas, K., Telkes, Z., Keszthelyi, L., Keszthelyi, M., Ács, N., Várbíró, S., & Török, M. (2025). Efficacy and Safety of Placental Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 17(24), 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243857