Intervention Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy at Japanese Company Cafeterias as a Practical Approach to Decrease Dietary Na/K and Prevent Hypertension

Abstract

1. Introduction

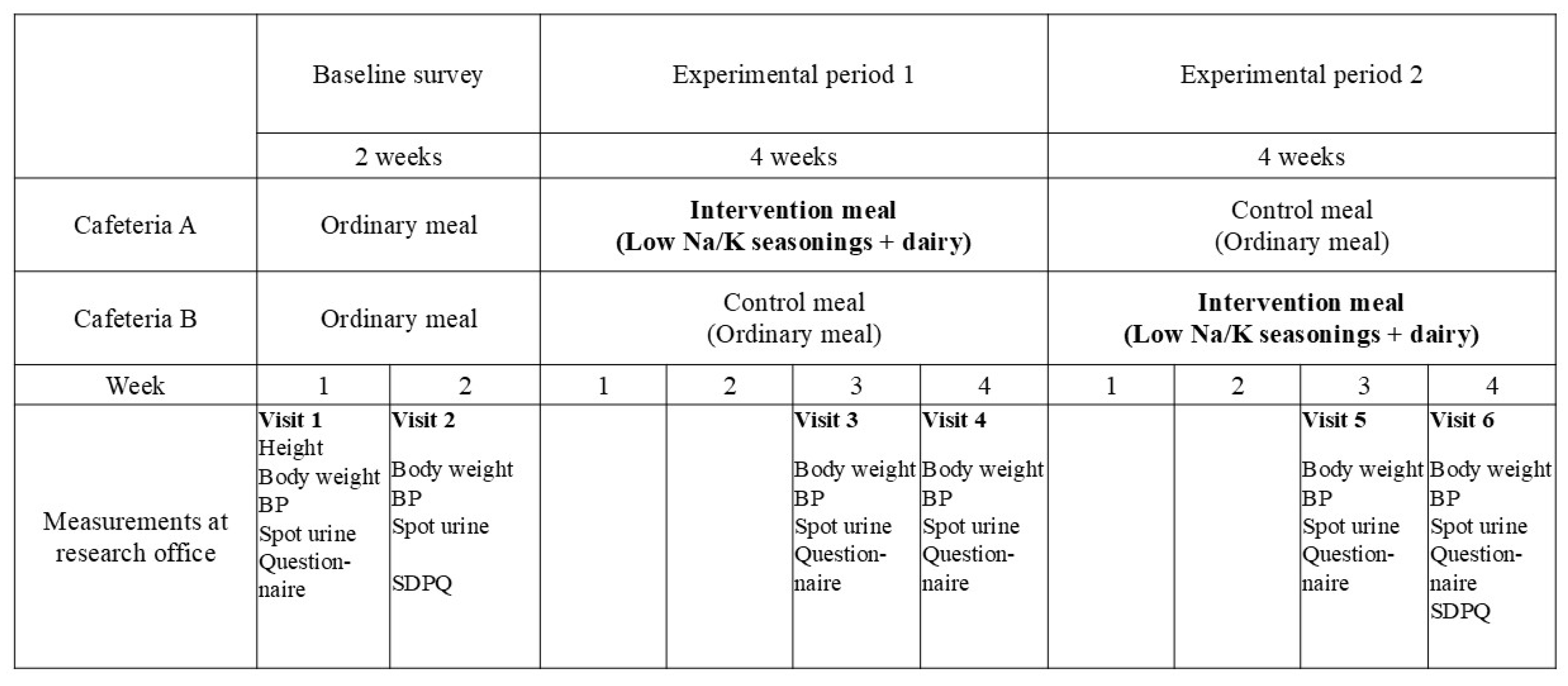

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

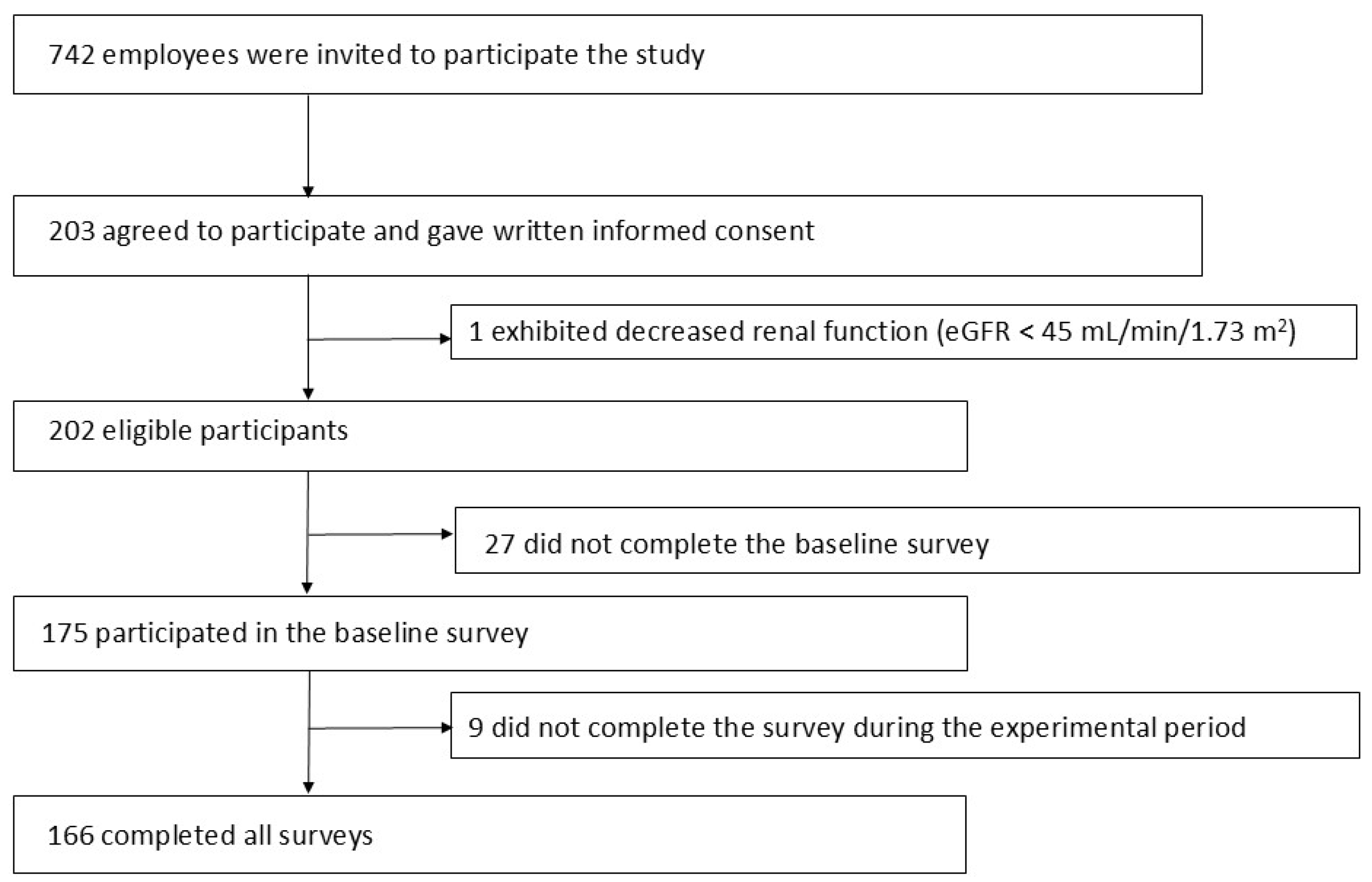

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements of the Na and K in the Meals

2.4. Outcomes and Measurements

2.5. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Baseline Survey

3.3. Na Content, K Content, and Na/K Ratio of the Cafeteria Meals Served

3.4. Cafeteria and Dairy Use

3.5. Measurements in the Control and Intervention Periods

3.6. Taste Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SDPQ | Short dietary propensity questionnaire |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- Kearney, P.M.; Whelton, M.; Reynolds, K.; Muntner, P.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005, 365, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.; Ng, C.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Kong, G.; Lin, C.; Chin, Y.H.; Lim, W.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Quek, J.; Fu, C.E.; et al. The global burden of metabolic disease: Data from 2000 to 2019. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 414–428 e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Nagai, M.; Ohkubo, T. Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan: Where are we now? Circ. J. 2013, 77, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozawa, A. Attributable fractions of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 21, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium; Magnussen, C.; Ojeda, F.M.; Leong, D.P.; Alegre-Diaz, J.; Amouyel, P.; Aviles-Santa, L.; De Bacquer, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A.; et al. Global Effect of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_14156.html (accessed on 26 November 2024). (In Japanese)

- WHO Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241504836 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- WHO Guideline: Potassium Intake for Adults and Children. Available online: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/potassium_intake/en/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- INTERSALTCooperative Research Group INTERSALT: An international study of electrolyte excretion blood pressure Results for 24 hour urinary sodium potassium excretion INTERSALTCooperative Research Group. BMJ 1988, 297, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Kogure, M.; Nakaya, N.; Hirata, T.; Tsuchiya, N.; Nakamura, T.; Narita, A.; Suto, Y.; Honma, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Miyagawa, K.; et al. Sodium/potassium ratio change was associated with blood pressure change: Possibility of population approach for sodium/potassium ratio reduction in health checkup. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 44, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.J.; Moore, T.J.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Vogt, T.M.; Cutler, J.A.; Windhauser, M.M.; et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, F.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Vollmer, W.M.; Appel, L.J.; Bray, G.A.; Harsha, D.; Obarzanek, E.; Conlin, P.R.; Miller, E.R.; Simons-Morton, D.G.; et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorling, E.; Niebuhr, D.; Kroke, A. Cost-effectiveness of salt reduction to prevent hypertension and CVD: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1993–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, F.C.; Morris, C.D.; Weinberger, M.H. Compliance to a low-salt diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 698S–703S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meader, N.; King, K.; Wright, K.; Graham, H.M.; Petticrew, M.; Power, C.; White, M.; Sowden, A.J. Multiple Risk Behavior Interventions: Meta-analyses of RCTs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e19–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Specter, S.E. Poverty and obesity: The role of energy density and energy costs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagahata, T.; Nakamura, M.; Ojima, T.; Kondo, I.; Ninomiya, T.; Yoshita, K.; Arai, Y.; Ohkubo, T.; Murakami, K.; Nishi, N.; et al. Relationships among Food Group Intakes, Household Expenditure, and Education Attainment in a General Japanese Population: NIPPON DATA2010. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, R.C.; Marklund, M.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Cobb, L.K.; Dalcin, A.T.; Henry, M.; Appel, L.J. Potassium-Enriched Salt Substitutes as a Means to Lower Blood Pressure: Benefits and Risks. Hypertension 2020, 75, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.-Y.; Hu, Y.-W.; Yue, C.-S.J.; Wen, Y.-W.; Yeh, W.-T.; Hsu, L.-S.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Pan, W.-H. Effect of potassium-enriched salt on cardiovascular mortality and medical expenses of elderly men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Wu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Tian, M.; Huang, L.; Li, Z.; et al. Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Jin, A.; Neal, B.; Feng, X.; Qiao, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Duan, P.; Cao, L.; et al. Salt substitution and salt-supply restriction for lowering blood pressure in elderly care facilities: A cluster-randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifelli, C.J.; Fulgoni, K.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Hess, J.M. Disparity in Dairy Servings Intake by Ethnicity and Age in NHANES 2015–2018. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2012–2016; Consumption. Available online: https://statline.rivm.nl/#/RIVM/nl/dataset/50038NED/table?ts=1641557938587 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Okuda, N.; Okayama, A.; Miura, K.; Yoshita, K.; Miyagawa, N.; Saitoh, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Sakata, K.; Chan, Q.; Elliott, P.; et al. Food Sources of Dietary Potassium in the Adult Japanese Population: The International Study of Macro-/Micronutrients and Blood Pressure (INTERMAP). Nutrients 2020, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.; Dyer, A.; Stamler, R. The INTERSALT study: Results for 24 hour sodium and potassium; by age and sex. J. Hum. Hypertens. 1989, 3, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Stamler, J.; Rose, G.; Elliott, P.; Dyer, A.; Marmot, M.; Kesteloot, H.; Stamler, R. Findings of the International Cooperative INTERSALT Study. Hypertension 1991, 17, I9–I15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.A.; Appel, L.J.; Okuda, N.; Brown, I.J.; Chan, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ueshima, H.; Kesteloot, H.; Miura, K.; Curb, J.D.; et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: The INTERMAP study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, N.; Higashiyama, A.; Tanno, K.; Yonekura, Y.; Miura, M.; Kuno, H.; Nakajima, T.; Nagahata, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Kosami, K.; et al. Na and K Intake from Lunches Served in a Japanese Company Cafeteria and the Estimated Improvement in the Dietary Na/K Ratio Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy to Prevent Hypertension. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, N.; Itai, K.; Okayama, A. Usefulness of a Short Dietary Propensity Questionnaire in Japan. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2018, 25, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueshima, H.; Okayama, A.; Saitoh, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Rodriguez, B.; Sakata, K.; Okuda, N.; Choudhury, S.; Curb, J. Differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors between Japanese in Japan and Japanese-Americans in Hawaii: The INTERLIPID study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2003, 17, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, N.; Miura, M.; Itai, K.; Morikawa, T.; Sasaki, J. Use of Lightly Potassium-Enriched Soy Sauce at Home Reduced Urinary Sodium-to-Potassium Ratio. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamura, T.; Miura, K.; Kadowaki, T.; Ueshima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Hashimoto, T. A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, S.; Arima, H.; Arima, S.; Asayama, K.; Dohi, Y.; Hirooka, Y.; Horio, T.; Hoshide, S.; Ikeda, S.; Ishimitsu, T.; et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019, 42, 1235–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Trieu, K.; Yoshimura, S.; Neal, B.; Woodward, M.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Li, Q.; Lackland, D.T.; Leung, A.A.; Anderson, C.A.M.; et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2020, 368, m315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Beneficial effects of potassium on human health. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburto, N.J.; Hanson, S.; Gutierrez, H.; Hooper, L.; Elliott, P.; Cappuccio, F.P. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013, 346, f1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, D.A.; Kazaks, A.G.; Geerling, J.C.; Stern, J.S.; Graudal, N.A. Normal range of human dietary sodium intake: A perspective based on 24-hour urinary sodium excretion worldwide. Am. J. Hypertens. 2013, 26, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisle, F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashiyama, A.; Okuda, N.; Kojima, K.; Morimoto, F.; Sugio, K.; Ueda, M.; Yonekura, Y.; Tanno, K.; Okayama, A. Knowledge on association between blood pressure and intake of sodium and potassium among Japanese workers. JJCDP 2023, 58, 229–238. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Jayedi, A.; Zargar, M.S. Dietary calcium intake and hypertension risk: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, L.; Weekes, J.; Carpenter, L. Effect of magnesium supplementation on blood pressure: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Z.; Rashidi Pour Fard, N.; Clark, C.C.T.; Haghighatdoost, F. Dairy products consumption and the risk of hypertension in adults: An updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1962–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Stamler, J.; Dennis, B.; Moag-Stahlberg, A.; Okuda, N.; Robertson, C.; Zhao, L.; Chan, Q.; Elliott, P. Nutrient intakes of middle-aged men and women in China, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States in the late 1990s: The INTERMAP study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2003, 17, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Leitner, G.; Merin, U. The Interrelationships between Lactose Intolerance and the Modern Dairy Industry: Global Perspectives in Evolutional and Historical Backgrounds. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7312–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, N.; Stamler, J.; Brown, I.J.; Ueshima, H.; Miura, K.; Okayama, A.; Saitoh, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Sakata, K.; Yoshita, K.; et al. Individual efforts to reduce salt intake in China, Japan, UK, USA: What did people achieve? The INTERMAP Population Study. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 2385–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Reducing population salt intake worldwide: From evidence to implementation. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 52, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.J.; Wang, J.; Sharkey, A.L.; Dowling, E.A.; Curtis, C.J.; Kessler, K.A. US Food Industry Progress Toward Salt Reduction, 2009–2018. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán, R.; Coltell, O.; Portolés, O.; Asensio, E.M.; Sorlí, J.V.; Ortega-Azorín, C.; González, J.I.; Sáiz, C.; Fernández-Carrión, R.; Ordovas, J.M.; et al. Bitter, Sweet, Salty, Sour and Umami Taste Perception Decreases with Age: Sex-Specific Analysis, Modulation by Genetic Variants and Taste-Preference Associations in 18 to 80 Year-Old Subjects. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahata, T.; Takahashi, N.; Fujii, M.; Asanuma, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Okayama, A.; Okuda, N. An event to experience alterations in the perception of saltiness applying adaptation to sodium chloride at a local health festival site, effectiveness of eating lightly flavored dishes first. JJCDP 2023, 58, 254–261. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- GBD Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, N.; Okayama, A.; Miura, K.; Yoshita, K.; Saito, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Sakata, K.; Miyagawa, N.; Chan, Q.; Elliott, P.; et al. Food sources of dietary sodium in the Japanese adult population: The international study of macro-/micronutrients and blood pressure (INTERMAP). Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Men (n = 102) | Women (n = 64) | p | Total (n = 166) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 44.8 | (11.3) | 43.5 | (12.0) | 0.493 | 44.3 | (11.5) | |

| Age group | 22–39 years | 35 | (34.3) | 26 | (40.6) | 0.210 | 61 | (36.7) |

| 40–49 years | 28 | (27.5) | 10 | (15.6) | 38 | (22.9) | ||

| 50–66 years | 39 | (38.2) | 28 | (43.8) | 67 | (40.4) | ||

| Awareness of hypertension a | 29 | (28.4) | 9 | (14.1) | 0.032 | 38 | (22.9) | |

| Use of antihypertensives | 13 | (12.7) | 3 | (4.7) | 0.087 | 16 | (9.6) | |

| Smoke | Current smoker | 16 | (15.7) | 4 | (6.3) | 0.001 | 20 | (12.0) |

| Never smoker | 57 | (55.9) | 57 | (89.1) | 114 | (68.7) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 29 | (28.4) | 3 | (4.7) | 32 | (19.3) | ||

| Having a low-salt diet | 20 | (19.6) | 10 | (15.6) | 0.516 | 30 | (18.1) | |

| Milk/yogurt consumption b, n (%) | ||||||||

| Do not consume | 16 | (15.7) | 6 | (9.4) | 0.556 | 22 | (13.3) | |

| ≤1 cup/week | 18 | (17.6) | 11 | (17.2) | 29 | (17.5) | ||

| 2–3 cups/week | 17 | (16.7) | 16 | (25.0) | 33 | (19.9) | ||

| 4–5 cups/week | 15 | (14.7) | 7 | (10.9) | 22 | (13.3) | ||

| 1 cup/day | 28 | (27.5) | 21 | (32.8) | 49 | (29.5) | ||

| ≥2 cups/day | 8 | (7.8) | 3 | (4.7) | 11 | (6.6) | ||

| Cafeteria use Cafeteria A | 61 | (59.8) | 21 | (32.8) | 0.001 | 82 | (49.4) | |

| Cafeteria B | 41 | (40.2) | 43 | (67.2) | 84 | (50.6) | ||

| Cafeteria use (/week), mean (SD) | 4.2 | (1.2) | 3.6 | (1.3) | 0.002 | 4 | (1.3) | |

| Men | Women | p | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 120.6 | (12.8) | 108.0 | (16.2) | <0.001 | 115.7 | (15.4) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.0 | (11.1) | 70.6 | (11.6) | <0.001 | 75.8 | (12.0) |

| BP category (including participants using antihypertensives) a | |||||||

| Normal BP (SBP < 120 and DBP < 80), n (%) | 45 | (44.1) | 49 | (76.6) | 0.001 | 94 | (56.6) |

| High normal BP (SBP 120–129 and/or DBP < 80), n (%) | 11 | (10.8) | 1 | (1.6) | 12 | (7.2) | |

| Elevated BP (SBP 130–139 and/or DBP 80–89), n (%) | 32 | (31.4) | 11 | (17.2) | 43 | (25.9) | |

| Hypertension (SBP ≥ 140 and/or DBP ≥ 90), n (%) | 14 | (13.7) | 3 | (4.7) | 17 | (10.2) | |

| Hypertension b, n (%) | 23 | (22.5) | 6 | (9.4) | 0.001 | 29 | (17.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 | (3.1) | 22.5 | (3.6) | 0.002 | 23.5 | (3.4) |

| Estimated 24 h urinary Na excretion c (mmol/24 h) | 160.1 | (31.6) | 144.5 | (25.9) | 0.001 | 154.1 | (30.4) |

| Estimated 24 h urinary K excretion c (mmol/24 h) | 38.7 | (9.0) | 33.8 | (6.5) | <0.001 | 36.8 | (8.4) |

| Urinary Na/K (mmol/mmol) | 4.01 | (1.89) | 4.20 | (2.00) | 0.549 | 4.09 | (1.93) |

| Na (mmol/Serving) | K (mmol/Serving) | Na/K Ratio (mmol/mmol) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | p | Mean | (SD) | p | Mean | (SD) | p | |

| Main dish for the Japanese set menu | |||||||||

| Control | 47.9 | (23.6) | 0.013 | 8.4 | (3.4) | <0.001 | 6.3 | (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 40.0 | (18.7) | 11.5 | (3.5) | 3.5 | (1.3) | |||

| Miso soup for the Japanese set menu | |||||||||

| Control | 26.8 | (3.4) | 0.413 | 1.4 | (0.2) | <0.001 | 19.2 | (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 26.4 | (4.0) | 3.5 | (0.6) | 7.7 | (1.2) | |||

| Japanese set menu (main dish + miso soup) | |||||||||

| Control | 74.2 | (23.6) | 0.008 | 9.9 | (3.4) | <0.001 | 8.2 | (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 66.4 | (18.4) | 15.1 | (4.7) | 4.6 | (1.2) | |||

| Noodle (soup and topping) | |||||||||

| Control | 80.4 | (14.8) | 0.008 | 4.1 | (1.5) | <0.001 | 22.7 | (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Intervention | 71.8 | (14.7) | 11.8 | (3.4) | 6.6 | (2.6) | |||

| Dairy (provided in the intervention meal period) a | |||||||||

| Regular milk (200 mL) | 3.8 | 7.9 | 0.5 | ||||||

| Low-fat milk (200 mL) | 4.1 | 9.2 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Low-fat yogurt (200 mL) | 3.9 | 8.5 | 0.5 | ||||||

| Control | Intervention | Difference (Intervention—Control) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SE) | (95%CI) | ||

| Cafeteria use (/week) | ||||||||

| Men | 4.4 | (0.9) | 4.3 | (1.0) | −0.07 | (0.1) | (−0.18, 0.04) | 0.232 |

| Women | 3.9 | (1.2) | 4.0 | (1.1) | 0.13 | (0.1) | (−0.08, 0.35) | 0.216 |

| Total | 4.2 | (1.1) | 4.2 | (1.0) | 0.01 | (0.1) | (−0.10, 0.11) | 0.868 |

| Use of dairy at the cafeteria in the intervention meal period (/week) | ||||||||

| Men | 4.3 | (1.2) | ||||||

| Women | 4.1 | (1.4) | ||||||

| Total | 4.2 | (1.3) | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| Men | 24.1 | (3.1) | 24.1 | (3.0) | 0.0 | (0.0) | (−0.1, 0.0) | 0.471 |

| Women | 22.46 | (3.66) | 22.54 | (3.65) | 0.08 | (0.03) | (0.00, 0.15) | 0.039 |

| Total | 23.5 | (3.4) | 23.5 | (3.3) | 0.0 | (0.0) | (−0.0, 0.1) | 0.410 |

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| Men | 120.5 | (10.8) | 121.0 | (11.8) | 0.6 | (0.6) | (−0.6, 1.8) | 0.333 |

| Women | 108.2 | (13.9) | 109.1 | (15.6) | 0.9 | (0.8) | (−0.7, 2.49) | 0.261 |

| Total | 115.7 | (13.4) | 116.4 | (14.6) | 0.7 | (0.5) | (−0.2, 1.5) | 0.141 |

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| Men | 78.8 | (9.6) | 79.2 | (9.6) | 0.4 | (0.5) | (−0.5, 1.3) | 0.371 |

| Women | 72.0 | (9.4) | 72.9 | (10.7) | 0.9 | (0.5) | (−0.2, 2.0) | 0.100 |

| Total | 76.2 | (10.0) | 76.8 | (10.5) | 0.6 | (0.4) | (−0.1, 1.3) | 0.089 |

| Urinary Na/K ratio (mmol/mmol) | ||||||||

| Men | 4.15 | (2.20) | 3.94 | (2.13) | −0.21 | (0.19) | (−0.59, 0.16) | 0.266 |

| Women | 4.02 | (2.24) | 3.31 | (1.39) | −0.71 | (0.24) | (−1.20, −0.22) | 0.005 |

| Total | 4.10 | (1.89) | 3.69 | (1.76) | −0.40 | (0.15) | (−0.11, −0.70) | 0.008 |

| Estimated 24 h urinary Na excretion (mmol/24 h) | ||||||||

| Men | 168.2 | (32.8) | 167.2 | (34.1) | −1.0 | (2.5) | (−6.1, 4.0) | 0.686 |

| Women | 149.1 | (28.7) | 141.7 | (31.5) | −7.4 | (3.0) | (−1.5, −13.3) | 0.015 |

| Total | 160.8 | (32.5) | 157.3 | (35.3) | −3.5 | (1.9) | (−7.3, 0.3) | 0.072 |

| Estimated 24 h urinary K excretion (mmol/24 h) | ||||||||

| Men | 39.6 | (9.1) | 41.9 | (10.5) | 2.2 | (0.2) | (0.7, 3.7) | 0.005 |

| Women | 35.3 | (6.5) | 36.9 | (7.2) | 1.6 | (0.8) | (0.0, 3.2) | 0.047 |

| Total | 38.0 | (8.5) | 40.0 | (9.7) | 2.0 | (0.6) | (0.9, 3.1) | 0.001 |

| Men | Women | pa (Men vs. Women) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Control meal | |||||||

| Fine | 79 | (82.3) | 33 | (58.9) | 0.001 | 112 | (73.7) |

| Strong | 13 | (13.5) | 22 | (39.3) | 35 | (23.0) | |

| Light | 4 | (4.2) | 1 | (1.8) | 5 | (3.3) | |

| Intervention meal | |||||||

| Fine | 72 | (73.5) | 35 | (62.5) | 0.117 | 107 | (69.5) |

| Strong | 21 | (21.4) | 20 | (35.7) | 41 | (26.6) | |

| Light | 5 | (5.1) | 1 | (1.8) | 6 | (3.9) | |

| pb (control vs. intervention) | 0.122 | 0.819 | 0.277 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okuda, N.; Higashiyama, A.; Tanno, K.; Yonekura, Y.; Miura, M.; Kuno, H.; Nakajima, T.; Tahara, E.; Morimoto, F.; Sugio, K.; et al. Intervention Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy at Japanese Company Cafeterias as a Practical Approach to Decrease Dietary Na/K and Prevent Hypertension. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243856

Okuda N, Higashiyama A, Tanno K, Yonekura Y, Miura M, Kuno H, Nakajima T, Tahara E, Morimoto F, Sugio K, et al. Intervention Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy at Japanese Company Cafeterias as a Practical Approach to Decrease Dietary Na/K and Prevent Hypertension. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243856

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkuda, Nagako, Aya Higashiyama, Kozo Tanno, Yuki Yonekura, Makoto Miura, Hiroshi Kuno, Toru Nakajima, Eiji Tahara, Fukiko Morimoto, Kozue Sugio, and et al. 2025. "Intervention Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy at Japanese Company Cafeterias as a Practical Approach to Decrease Dietary Na/K and Prevent Hypertension" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243856

APA StyleOkuda, N., Higashiyama, A., Tanno, K., Yonekura, Y., Miura, M., Kuno, H., Nakajima, T., Tahara, E., Morimoto, F., Sugio, K., Kojima, K., Nagahata, T., Taniguchi, H., & Okayama, A. (2025). Intervention Using Low-Na/K Seasonings and Dairy at Japanese Company Cafeterias as a Practical Approach to Decrease Dietary Na/K and Prevent Hypertension. Nutrients, 17(24), 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243856