Food Allergy and Foodservice: A Comparative Study of Allergic and Non-Allergic Consumers’ Behaviors, Attitudes, and Risk Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Instrument

2.2. Target Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Margin of Error

3.2. Respondents’ Characteristics

3.3. Frequency of Consumption of Food Prepared in Foodservice Establishments (FSEs)

3.4. Barriers When Dining Out/Ordering Food

3.5. Cost of Dining Out/Ordering Food

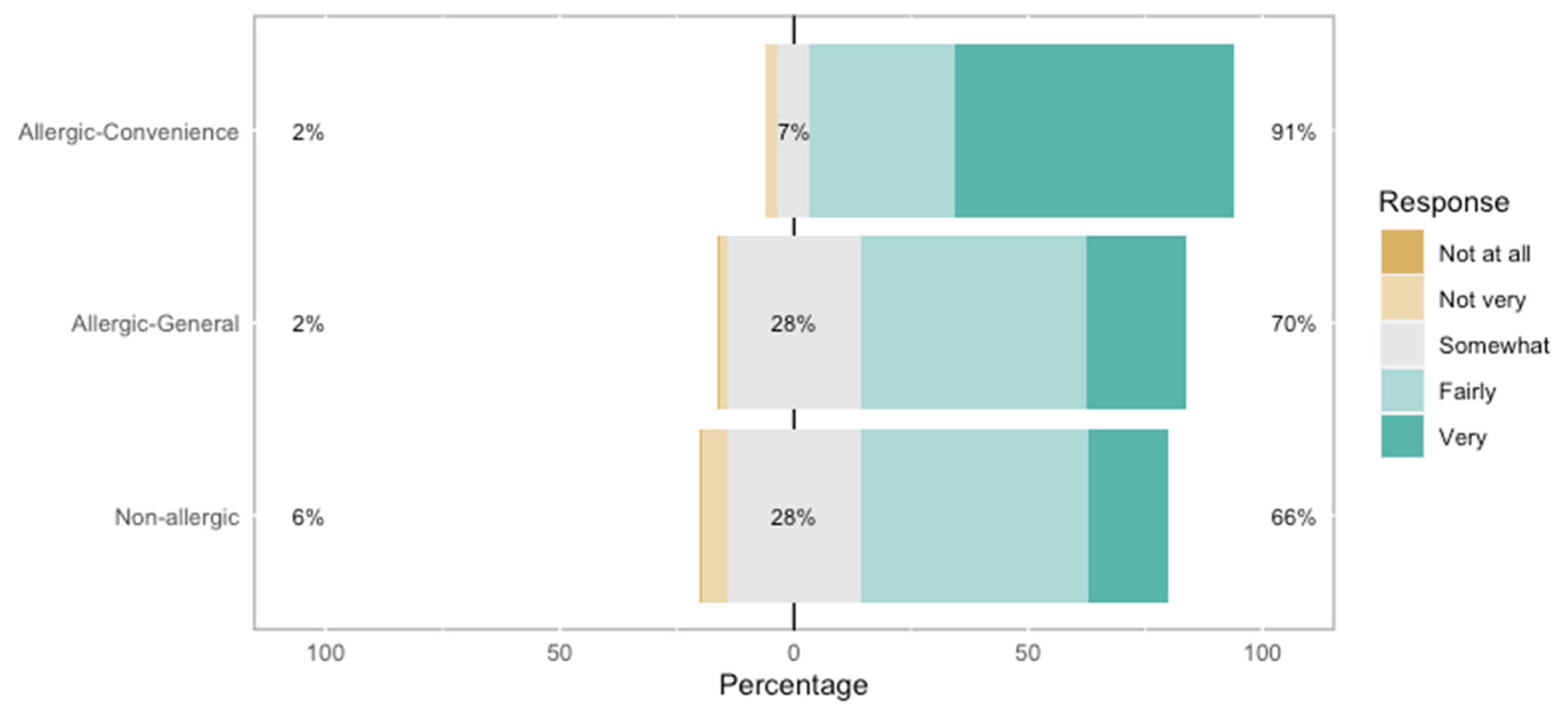

3.6. Selection of FSEs

3.7. Loyalty

3.8. Focus on the Experiences of Allergic Consumers When Dining Out or Ordering Food

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FSEs | Foodservice establishments |

| FA | Food-allergic |

References

- Sampath, V.; Sindher, S.B.; Alvarez Pinzon, A.M.; Nadeau, K.C. Can food allergy be cured? what are the future prospects? Allergy 2020, 75, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. The Prevalence of Food Allergies in Canada. 2016. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/food-allergies-intolerances/food-allergen-research-program/research-related-prevalence-food-allergies-intolerances.html (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Clarke, A.E.; Elliott, S.J.; St Pierre, Y.; Soller, L.; La Vieille, S.; Ben-Shoshan, M. Temporal trends in prevalence of food allergy in Canada. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1428–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, A.W.; Sampson, H.A.; Plaut, M.; Lack, G.; Akdis, C.A. Treatment for food allergy. Am. Acad. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 141, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Burks, A.W. Food allergy immunotherapy: Oral immunotherapy and epicutaneous immunotherapy. Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 75, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, J.A.; Kim, E.H. New approaches to food allergy immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 12, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravid, N.L.; Annuziato, R.A.; Ambrose, M.A.; Chuang, K.; Mullarkey, C.; Sicherer, S.H.; Shemesh, E.; Cox, A.L. mental health and quality-of-life concerns related to the burden of food allergy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. 2012, 32, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soller, L.; Ben-Shoshan, M.; Harrington, D.W.; Knoll, M.; Fragapane, J.; Joseph, L.; St. Pierre, Y.; La Vieille, S.; Wilson, K.; Elliott, S.J.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of food allergy in Canada: A focus on vulnerable populations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2015, 3, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriel, R.C.; Waqar, O.; Sharma, H.P.; Casale, T.B.; Wanget, J. Characteristics of food allergic reactions in united states restaurants. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosty, C.; Colli, M.D.; Gabrielli, S.; Clarke, A.E.; Morris, J.; Gravel, J.; Lim, R.; Chan, E.S.; Goldman, R.D.; O’Keefe, A.; et al. Impact of reaction setting on the management, severity, and outcome of pediatric food-induced anaphylaxis: A cross-sectional study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versluis, A.; Knulst, A.C.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Michelsen, A.; Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L.; Van Os-Medendorp, H. Frequency, severity and causes of unexpected allergic reactions to food: A systematic literature review. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sicherer, S.H.; Bakhl, K.; Wang, K.; Stoffels, G.; Oriel, R.C. Restaurant takeout practices of food allergic individuals and associated allergic reactions in the COVID-19 era. J. Allergy Immunol. Clin. Pract. 2022, 10, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Vasileiou, K.; Lucas, J.S. Conversations about food allergy risk with restaurant staff when eating out: A customer perspective. Food Control 2020, 108, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.J.; Arasi, S.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Baseggio Conrado, A.; Deschildre, A.; Gerdts, J.; Halken, S.; Muraro, A.; Patel, N.; Van Ree, R.; et al. Risk factors for severe reactions in food allergy: Rapid evidence review with meta-analysis. Eur. Acad. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 2634–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begen, F.M.; Barnett, J.; Barber, M.; Payne, R.; Gowland, M.H.; Lucas, J.S. Parents’ and caregivers’ experiences and behaviours when eating out with children with a food hypersensitivity. BioMed Cent. Public Health 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchforth, E.; Weaver, S.; Willars, J.; Wawrzkowicz, E.; Luyt, D. Dixon-Woods, M. A qualitative study of families of a child with a nut allergy. Chronic Illn. 2011, 7, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, G.A.; Warren, C.M.; Gupta, R.; Sindher, S.B.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; Nadeauet, K.C. Food allergy risks and dining industry—An assessment and a path forward. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1060932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftwich, J.; Barnett, J.; Muncer, K.; Shepherd, R.; Raats, M.M.; Hazel Gowland, M.; Lucas, J.S. The challenges for nut-allergic consumers of eating out. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begen, F.M.; Barnett, J.; Payne, R.; Roy, D.; Gowland, M.H.; Lucas, J.S. Consumer preferences for written and oral information about allergens when eating out. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janković, V.; Raljić, J.P.; Đorđević, V. Public protection–reliable allergen risk management. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 85, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.; Théolier, J.; Gerdts, J.; Benrejeb Godefroy, S. Dining out with food allergies: Two decades of evidence calling for enhanced consumer protection. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, D.; Sharma, D. Online food delivery portals during COVID-19 times: An analysis of changing consumer behavior and expectations. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Wen, H. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors about dining out with food allergies: A cross-sectional survey of restaurant customers in the United States. Food Control 2020, 107, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Calvo, R.; Hidalgo-Víquez, C.; Mora-Villalobos, V.; GonzalezVargas, M.G.; Alvarado, R.; Peña-Vasquez, M.; Barboza, N.; Redondo-Solano, M. Analysis of knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) regarding food allergies in social network users in Costa Rica. Food Control 2022, 138, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenblätter, J.; Schumacher, G.; Hirt, M.; Wild, J.; Catalano, L.; Schoenberg, S.; Baru, B.; Jent, S. How do food businesses provide information on allergens in non-prepacked foods? A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. Allergo J. Int. 2022, 31, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasha’s Law: UK Statutory Instruments. The Food Information (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2019/1218/made (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Alghafari, W.T.; Attar, A.A.; Alghanmi, A.A.; Alolayan, D.A.; Alamri, N.A.; Alqarni, S.A.; Alsahafi, A.M.; Arfaoui, L. Responses of consumers with food allergy to the new allergen-labelling legislation in Saudi Arabia: A preliminary survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5941–5952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Food and Drug Regulations. 2023. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/c.r.c.,_c._870/index.html (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Konstantinou, G.N.; Pampoukidou, O.; Sergelidis, D.; Fotoulaki, M. Managing food allergies in dining establishments: Challenges and innovative solutions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Lee, Y.M. Exploration of past experiences, attitudes and preventive behaviors of consumers with food allergies about dining out: A focus group study. Food Prot. Trends 2012, 32, 736–746. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.A.; Pistier, M. Food allergy in restaurants work group report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingate, T.G.; Jones, S.K.; Khakhar, M.K.; Bourdage, J.S. Speaking of allergies: Communication challenges for restaurant staff and customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, B.; Deng, A.; McLaurin, T. Food allergy knowledge, attitudes, and resources of restaurant employees. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2681–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, M. Serving up allergy labeling: Mitigating food allergen risks in restaurants. Or. Law Rev. 2018, 97, 109–182. [Google Scholar]

- Odisho, N.; Carr, T.F.; Cassell, H. Food Allergy: Labelling and exposure risks. J. Food Allergy 2020, 2, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Allergy Canada (FAC). How to Read Food Labels. 2024. Available online: https://foodallergycanada.ca/allergy-safety/food-labelling/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Brewer, M.S.; Rojas, M. Consumer attitudes toward issues in food safety. J. Food Saf. 2008, 28, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolek, S. Consumer knowledge, attitudes, and judgments about food safety: A consumer Analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 102, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Nikolic, A.; Mujcinovic, A.; Blazic, M.; Herljevic, D.; Goel, G.; Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Guiné, R.; Gonçalves, J.C.; et al. How do consumers perceive food safety risks? —Results from a multi-country survey. Food Control 2022, 142, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Clingenpeel, M.; Greenhawt, M.; Shaker, M. Reporting guidelines for allergy and immunology survey research. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 130, 674–680.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Dennis, M.; Higgins, L.A.; Lee, A.R.; Sharrett, M.K. Gluten-free diet survey: Are Americans with coeliac disease consuming recommended amounts of fiber, iron, calcium and grain foods? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 8, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, S.L. Sampling: Design and Analysis, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrix, X.M. What Is Non-Probability Sampling? Everything You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/non-probability-sampling/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Hedt, B.L.; Pagano, M. Health indicators: Eliminating bias from convenience sampling estimators. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, J.; Robert, M.-C. Challenges and path forward on mandatory allergen labeling and voluntary precautionary allergen labeling for a global company. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 101, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryer, J.; Speerschneider, K. R Package, Version 1.3.5.; Likert: Analysis and Visualization Likert Items; Albany (New York), the United States. 2016. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=likert (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Statistics Canada. 2024. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241217/dq241217c-eng.htm (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Allen, C.W.; Bidarkar, M.S.; van Nunen, S.A.; Campbell, D.E. Factors impacting parental burden in food-allergic children. J. Pediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.; Waserman, S.; Gerdts, J.; Povolo, B.; Bonvalot, Y.; La Vieille, S. A survey of allergic consumers and allergists on precautionary allergen labelling: Where do we go from here? Nutrients 2025, 17, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanich, N.; Weiss, C.; Furlong, T.J.; Sicherer, S.H. Food allergic consumer (FAC) experience in restaurants and food establishments. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Sauer, K.L.; Wen, H.; Bisges, E. Myers, L. Dining experiences of customers with food allergies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, A57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandabach, K.H.; Ellsworth, A.; Vanleeuwen, D.M.; Blanch, G.; Waters, H.L. Restaurant managers’ knowledge of food allergies: A comparison of differences by chain or independent affiliation, type of service and size. J. Culin. Sci. 2005, 4, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Kwon, J. Food allergy risk communication in restaurants. Food Prot. Trends 2016, 36, 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Park, E.; Tao, C.-W.; Chae, B.; Li, X.; Kwon, J. Exploring user-generated content related to dining experiences of consumers with food allergies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Sozen, E.; Wen, H. A qualitative study of food choice behaviors among college students with food allergies in the US. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1732–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, M.; Dorosti, A.; Rahnama, A.; Hoseinpour, A. Evaluation of factors affecting customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 5039–5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. How reputation creates loyalty in the restaurant sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaihani, F.M.F.; Ali, N.Z. Factors affecting customer loyalty in the restaurant service industry in Kuwait city, Kuwait. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, J.L. To Eat or Not to Eat: How Ohio can foster confidence between restaurants and food allergic individuals. Univ. Dayt. Law Rev. 2016, 41, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Kwon, J. Restaurant servers’ risk perceptions and risk communication- related behaviors when serving customers with food allergies in the U.S. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.B.; Hattersley, S.; Allen, K.J.; Beyer, K.; Chan, C.H.; Godefroy, S.B.; Hodgson, R.; Mills, E.N.C.; Muñoz-Furlong, A.; Schnadt, S.; et al. Can we define a tolerable level of risk in food allergy? Report from a EuroPrevall/UK Food Standards Agency workshop. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.H.; Rajagopal, L. Food allergy knowledge, attitudes, practices, and training of foodservice workers at a university foodservice operation in the midwestern United States. Food Control 2013, 31, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen, A.R.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Bonanno, A.; Bremer, M.G.E.G. Financial burden of allergen free food preparation in the catering business. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2016, 8, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, J.M.; Manning, L. “May Contain” Allergen Statements: Facilitating or frustrating consumers? J. Consum. Policy 2018, 40, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affidia. Italy: Girl Died from Allergic Reaction to Dairy-Contaminated Vegan Tiramisu. 2023. Available online: https://affidiajournal.com/en/italy-girldied-from-allergic-reaction-to-dairy-contaminated-vegan-tiramisu (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Wen, H.; Lee, Y.M. Effects of message framing on food allergy communication: A cross-sectional study of restaurant customers with food allergies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, J.M.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Grasso, D. “Know before You Serve” Developing a Food-Allergy Fact Sheet. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.; Sicherer, S.H. Food allergy management from the perspective of restaurant and food establishment personnel. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 98, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, S.A. Food allergy risk management: More customers, less liability. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2012, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevel, R.W.R.; Cochrane, S.A. Food safety assurance systems. In Management of Allergen in Food Industry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.; Théolier, J.; Lizée1, K.; Povolo, B.; Gerdts, J.; Godefroy, S.B. “Vegan” and “plant-based” claims: Risk implications for milk- and egg-allergic consumers in Canada. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Plant-Based Protein Market: Global and Canadian Market Analysis. 2019. Available online: https://nrc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2019-10/Plant_protein_industry_market_analysis_summary.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Yang, L.G.; Brewster, R.K.; Donnell, M.T.; Hirani, R.N. Risk characterisation of milk protein contamination in milk-alternative ice cream products sold as frozen desserts in the United States. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2022, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiner, D.J. Convenience samples from online respondent pools: A case study of the sosci panel. Stud. Commun. Media 2014, 5, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Adams, A.E.; Elsasser, S. Digital inequality and place: The effects of technological diffusion on internet proficiency and usage across rural, suburban, and urban counties. Sociol. Inq. 2009, 79, 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | No Food Allergies | Food-Allergic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience | General | ||

| Sample size | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Weighted sample size | N/A | 390 | 610 |

| Age (most common) | 35–54 years (41%) | 35–54 years (47%) | 35–54 years (37%) |

| Income (most common) | <CAD 100,000 (52%) | >CAD 100,000 (61%) | <CAD 100,000 (62%) |

| F (50%); M (49.9%); Other/no answer (0.1%) | F (72%); M (26%); Other/no answer (2%) | F (35.8%); M (63.9%); Other/no answer (0.3%) | |

| Respondent status | N/A | Adult with food allergy (57%); Parent of child with food allergy (43%) | Adult with food allergy (68%); Parent of child with food allergy (32%) |

| Date of food allergy diagnosis (most common) 1 | >10 years from survey (59%) | Within 5 years from survey (42%) | |

| Diagnosed by 1 | Allergist/immunologist (86%); Family physician (25%) | Allergist immunologist (51%); Family physician (53%) | |

| Number of allergies (most common) 1 | Multiple (75%) | Single (56%) | |

| Allergen (most common) 1 | Peanuts (61%); Tree nuts (61%) | Peanuts (35%); Tree nuts (26%) | |

| Allergen (least common) | Mustard (4%) | Mustard (3%) | |

| Prescribed epinephrine autoinjector (most common) 1 | Yes (93%) | Yes (54%) | |

| Service Format | Frequency | No Food Allergies 1 | Food-Allergic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience 2 | General 3 | |||

| Dining in a restaurant | ≥1× week | 27% | 14% (*) | 26% |

| <1× week 4 | 68% | 73% | 72% | |

| Never | 5% | 13% (*) | 2% (*) | |

| Ordering take-out or delivery directly from a restaurant | ≥1× week | 34% | 19% (*) | 35% |

| <1× week 4 | 59% | 61% | 57% | |

| Never | 7% | 20% (*) | 8% | |

| Ordering delivery through a 3rd-party service | ≥1× week | 20% | 6% (*) | 29% (*) |

| <1× week 4 | 45% | 28% (*) | 46% | |

| Never | 35% | 66% (*) | 25% (*) |

| Establishment Type | Frequency | No Food Allergies 1 | Food-Allergic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience 2 | General 3 | |||

| Fast food/quick service | ≥1× week | 41% | 21% (*) | 41% |

| <1× week | 57% | 63% | 56% | |

| Never | 2% | 16% (*) | 3% | |

| Full-service chains | ≥1× week | 10% | 6% (*) | 11% |

| <1× week | 78% | 80% | 79% | |

| Never | 12% | 14% | 10% | |

| Independent (e.g., smaller, privately owned restaurants) | ≥1× week | 17% | 7% (*) | 18% |

| <1× week 4 | 77% | 74% | 77% | |

| Never | 6% | 19% (*) | 5% | |

| Specific type of international cuisine | ≥1× week | 14% | 4% (*) | 15% |

| <1× week 4 | 78% | 52% (*) | 75% | |

| Never | 8% | 44% (*) | 10% | |

| No Food Allergies 1 | Food-Allergic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience 2 | General 3 | ||

| When dining out | |||

| Barrier #1 | Cost/too expensive (65%) | Risk of cross-contamination with food allergens (79%) | Cost/too expensive (45%) |

| Barrier #2 | Prefer home-cooked meals (30%) | Lack of access to ingredient information for menu items (73%) | Risk of cross-contamination with food allergens (37%) |

| Barrier #3 | Not convenient (24%) | Meals are not guaranteed to be safe (69%) | My child has had/I have had an allergic reaction in the past (35%) |

| When ordering food | |||

| Barrier #1 | Cost/too expensive (60%) | Risk of cross-contamination with food allergens (73%) | Cost/too expensive (43%) |

| Barrier #2 | Prefer home-cooked meals (25%) | Lack of access to ingredient information for menu items (66%) Not confident the restaurant will understand my child’s/my specific food allergy (66%) | Risk of cross-contamination with food allergens (38%) |

| Barrier #3 | Dining out/ordering food from a restaurant is unhealthy (23%) | Meals are not guaranteed to be safe (65%) | Meals are not guaranteed to be safe (36%) |

| No Food Allergies 1 | Food-Allergic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience 2 | General 3 | ||

| Factor #1 | Has great-tasting food (82%) | Willingly accommodates food allergies and dietary observations/restrictions/aversions (98%) | Has great-tasting food (79%) |

| Factor #2 | Is reasonably priced (77%) | Is an establishment I feel safe eating at/ordering food from (97%) | Always gets my order correct (77%) |

| Factor #3 | Uses fresh, good-quality ingredients (73%) | Is always consistent (89%) | Uses fresh, good-quality ingredients (75%) |

| Food-Allergic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Convenience 1 | General 2 | |

| Reason #1 | Communication/staff’s ability to communicate (24%) | Accommodation/willingness to accommodate (20%) |

| Reason #2 | Accommodation/willingness to accommodate (23%) Prefer a familiar/trusted restaurant (23%) | Taking precautions (19%) |

| Reason #3 | Taking precautions (21%) | Type of allergy (12%) |

| Food-Allergic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Convenience 1 | General 2 | |

| Reason #1 | Lack of accommodation (40%) | Lack of accommodation (21%) |

| Reason #2 | Negative previous experiences (21%) | Lack of trust/fear (20%) |

| Reason #3 | Communication/staff’s ability to communicate (19%) | Ability to guarantee safety (19%) |

| No Food Allergies | Food-Allergic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General | Convenience | ||

| Barriers to dining out or ordering food | |||

| Cost | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Risk of allergen cross-contamination | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Meals are not guaranteed to be safe | ✓ | ✓ | |

| FSE selection factors | |||

| Taste | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ingredient quality | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Consistency, serving correct order | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Availability of ingredient information | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Willingness to accommodate | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Perceptions when dining out or ordering food | |||

| FSEs do not understand seriousness of food allergy | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Feel safe when dining out | ✓ | ✓ | |

| There are many safe options | ✓ | ||

| Feeling of safety when dining out or ordering food | |||

| Willingness to accommodate (FSE) | N/A | ✓ | ✓ |

| Taking precautions (consumer with food allergy) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Availability of ingredient information (FSE) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dedicated area to prepare meals for consumers with food allergy (FSE) | ✓ | ✓ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shirani, F.; Dominguez, S.; Théolier, J.; Gerdts, J.; Reid, K.; La Vieille, S.; Godefroy, S. Food Allergy and Foodservice: A Comparative Study of Allergic and Non-Allergic Consumers’ Behaviors, Attitudes, and Risk Perceptions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182916

Shirani F, Dominguez S, Théolier J, Gerdts J, Reid K, La Vieille S, Godefroy S. Food Allergy and Foodservice: A Comparative Study of Allergic and Non-Allergic Consumers’ Behaviors, Attitudes, and Risk Perceptions. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182916

Chicago/Turabian StyleShirani, Fatemeh, Silvia Dominguez, Jérémie Théolier, Jennifer Gerdts, Kate Reid, Sébastien La Vieille, and Samuel Godefroy. 2025. "Food Allergy and Foodservice: A Comparative Study of Allergic and Non-Allergic Consumers’ Behaviors, Attitudes, and Risk Perceptions" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182916

APA StyleShirani, F., Dominguez, S., Théolier, J., Gerdts, J., Reid, K., La Vieille, S., & Godefroy, S. (2025). Food Allergy and Foodservice: A Comparative Study of Allergic and Non-Allergic Consumers’ Behaviors, Attitudes, and Risk Perceptions. Nutrients, 17(18), 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182916