Unraveling Future Trends in Free School Lunch and Nutrition: Global Insights for Indonesia from Bibliometric Approach and Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliometric Findings

3.1.1. Time Distribution of Research

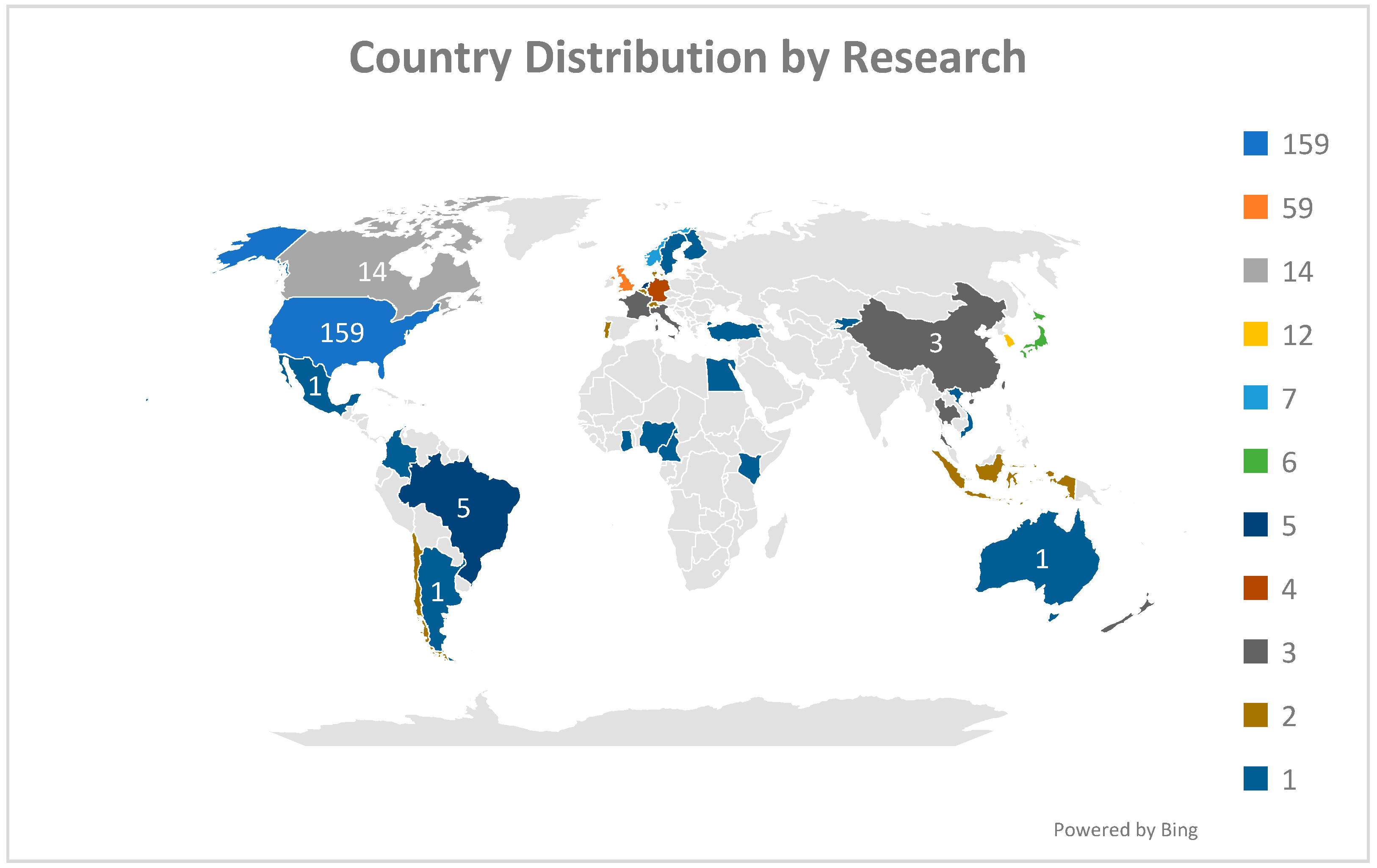

3.1.2. Country Distribution of Research

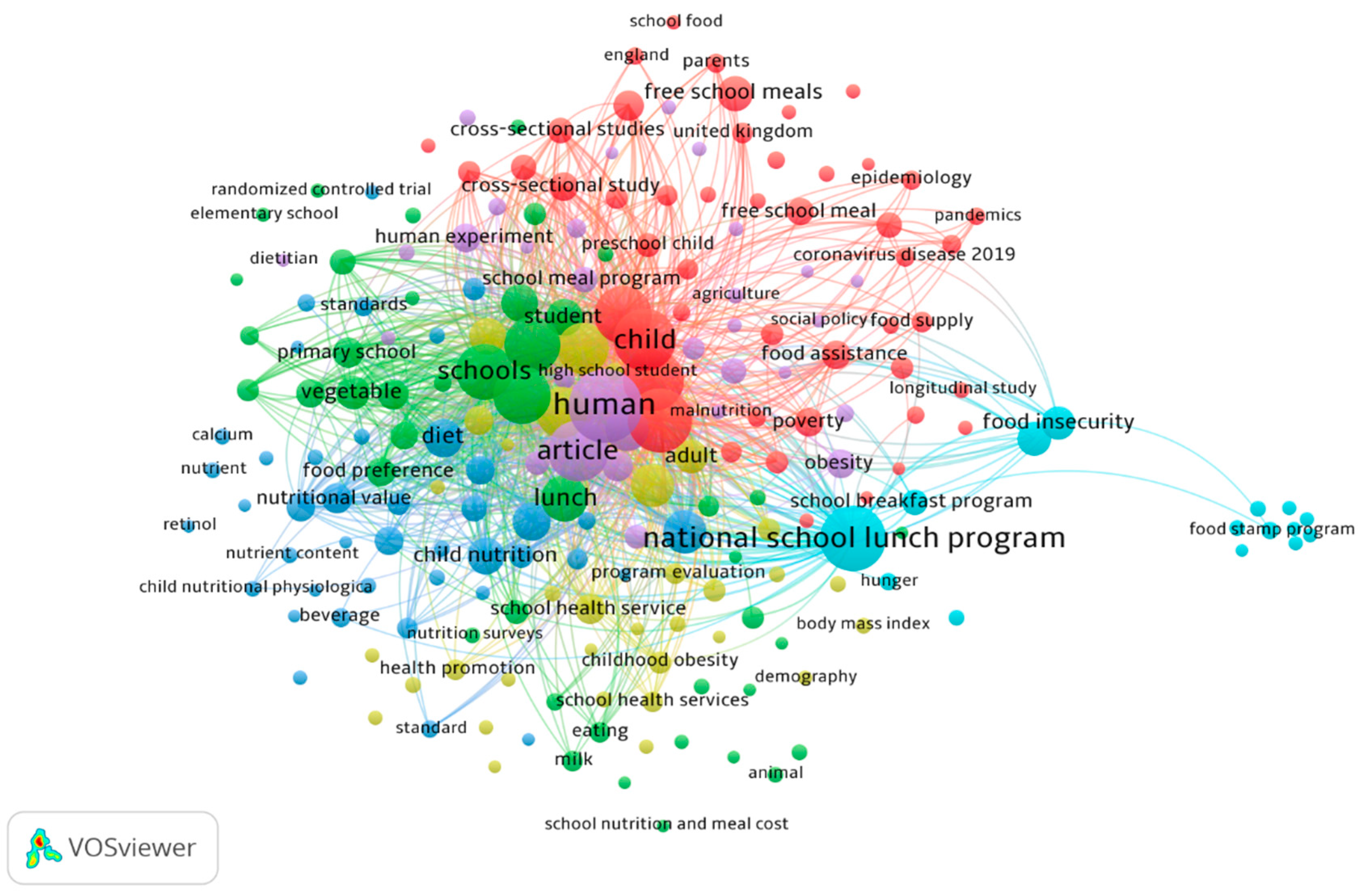

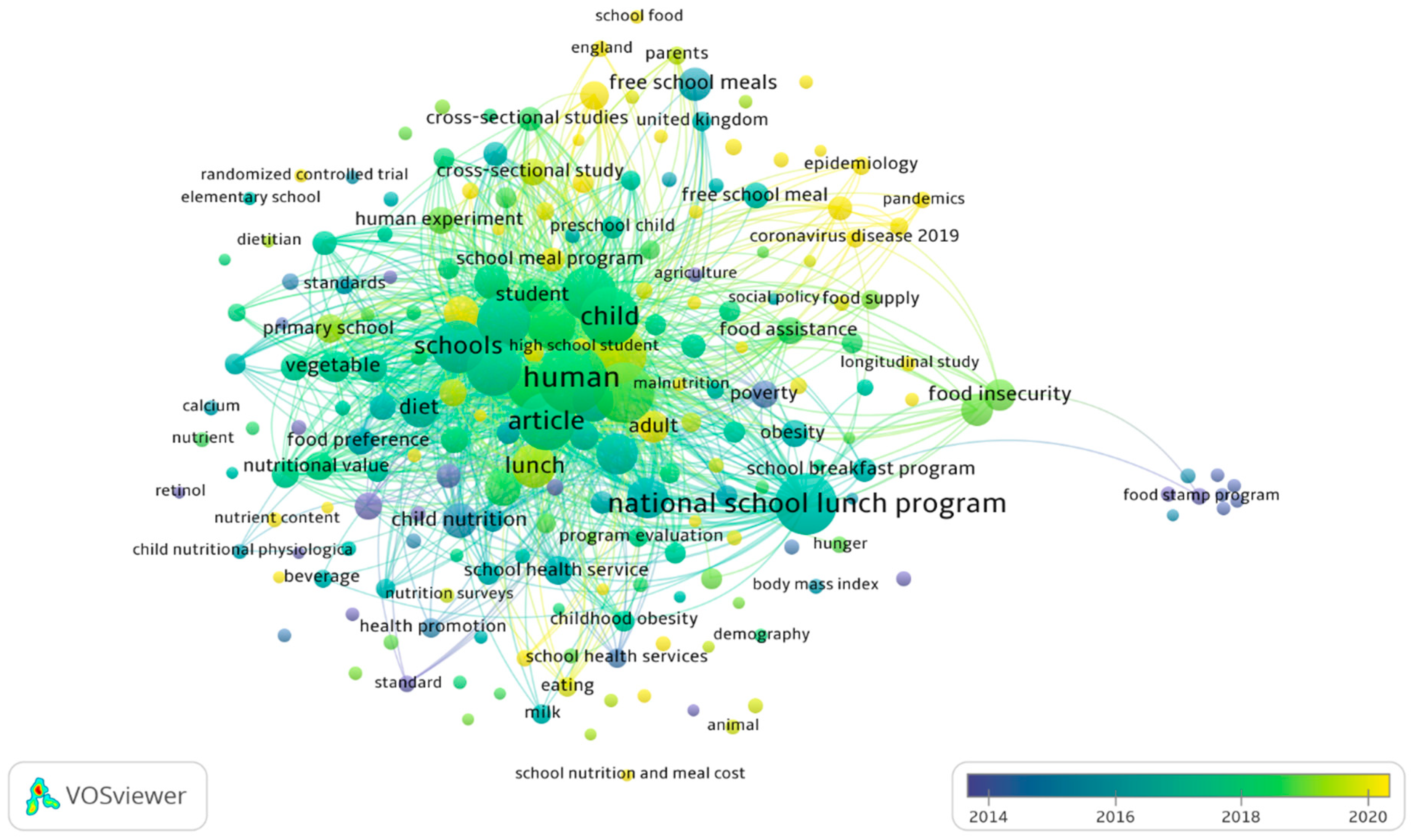

3.1.3. Keywords Clusterization and Trend

3.1.4. Early Research Focus (2014–2016, Purple-Blue Keywords)

3.1.5. Mid-Period Research Themes (2016–2018, Green Keywords)

3.1.6. Recent Trends and Emerging Topics (2018–Ongoing, Yellow Keywords)

3.2. Literature Review

3.2.1. Existing Guideline for School Lunch Program

3.2.2. Purpose of School Lunch Program

3.2.3. The Price of the Program: Universal vs. Subsidized

3.2.4. Appropriate Targeting for Program Participant (Equality, Demographic, Justice, or Equity)

3.2.5. Revealed Impacts of School Lunch Program on Nutrition and Health

3.2.6. Key Success Factors

3.2.7. Barriers to a Successful School Lunch Program

3.3. Implication for Indonesian School Lunch Program: Redefining Purposes

3.3.1. Redefining the Purpose of School Lunch Program for Indonesia

3.3.2. Cost Models in the MBG Program: Universal vs. Subsidized

3.3.3. Targeting Beneficiaries in the MBG Program: Equity and Justice Perspective

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naspolini, N.F.; Schüroff, P.A.; Vanzele, P.A.R.; Pereira-Santos, D.; Valim, T.A.; Bonham, K.S.; Fujita, A.; Passos-Bueno, M.R.; Beltrão-Braga, P.C.B.; Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F.; et al. Exclusive Breastfeeding Is Associated with the Gut Microbiome Maturation in Infants According to Delivery Mode. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2493900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/joint-child-malnutrition-estimates-unicef-who-wb (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ashar, H.; Laksono, A.D.; Supadmi, S.; Kusumawardani, H.D.; Yunitawati, D.; Purwoko, S.; Khairunnisa, M. Factors Related to Stunting in Children under 2 Years Old in the Papua, Indonesia: Does the Type of Residence Matter? Saudi Med. J. 2024, 45, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendana, P.; Kim, S.-Y. Maternal Factors and Breastfeeding Practices Associated with Stunting among Indonesian Children Aged 6 to 23 Months. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2025, 37, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yantri, N.F.; Simbolon, D.; Agustina, D.; Syaefatul, D.; Firnawati, F.; Hertipa, F.; Febryanti, F.; Putri, O.J. The Proportion of Animal Protein Consumption with A Prevalence of Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight in Toddlers in Indonesia. Proceeding Int. Conf. Health Polytech. Jambi 2025, 5, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Azriani, D.; Masita; Qinthara, N.S.; Yulita, I.N.; Agustian, D.; Zuhairini, Y.; Dhamayanti, M. Risk Factors Associated with Stunting Incidence in under Five Children in Southeast Asia: A Scoping Review. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.; Alaaraj, N.; Ahmed, S.; Alyafei, F.; Hamed, N. Early and Long-Term Consequences of Nutritional Stunting: From Childhood to Adulthood. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, D.; Gentilini, U.; Schultz, L.; Bedasso, B.; Singh, S.; Okamura, Y.; Iyengar, H.T.; Blakstad, M. School Meals, Social Protection, and Human Development: Revisiting Trends, Evidence, and Practices in South Asia and Beyond; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- An Agenda to Combat Child Hunger; Strengthen Equity School Feeding and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://schoolmealscoalition.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/ODI_School_feeding_and_the_SDGs.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Open Knowledge Repository. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstreams/66305c9b-a4c8-52c2-89c9-19d1b219862d/download (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Busey, E.A.; Chamberlin, G.; Mardin, K.; Perry, M.; Taillie, L.S.; Dillman Carpentier, F.R.; Popkin, B.M. National Policies to Limit Nutrients, Ingredients, or Categories of Concern in School Meals: A Global Scoping Review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2024, 8, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.A.; Harvey, S.P.; Spaeth, K.; Sullivan, D.K.; Lambourne, K.; Kunkel, G.H. Farm to School, School to Home: An Evaluation of a Farm to School Program at an Urban Core Head Start Preschool Program. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2014, 9, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C.; Power, M.; Moss, R.H.; Lockyer, B.; Burton, W.; Doherty, B.; Bryant, M. Are Free School Meals Failing Families? Exploring the Relationship between Child Food Insecurity, Child Mental Health and Free School Meal Status during COVID-19: National Cross-Sectional Surveys. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. The Reliability of Free School Meal Eligibility as a Measure of Socio-Economic Disadvantage: Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study in Wales. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 66, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, G.A.; Faulks, J.; Swift, J.A.; Mhesuria, J.; Jethwa, P.; Pearce, J. Factors Associated with Universal Infant Free School Meal Take up and Refusal in a Multicultural Urban Community. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnham, J.C.; McKevitt, S.; Vamos, E.P.; Laverty, A.A. Evidence Use in the UK’s COVID-19 Free School Meals Policy: A Thematic Content Analysis. Policy Des. Pract. 2023, 6, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, A.; Bayes, N.; Bradley, S.; Kay, A.D.; Jones, P.G.W.; Ryan, D.J. A Mixed-Method Process Evaluation of an East Midlands County Summer 2021 Holiday Activities and Food Programme Highlighting the Views of Programme Co-Ordinators, Providers, and Parents. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 912455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guio, A.-C. Free School Meals for All Poor Children in Europe: An Important and Affordable Target? Child. Soc. 2023, 37, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C.; Roos, E.; Brug, J.; Behrendt, I.; Ehrenblad, B.; Yngve, A.; te Velde, S.J. Role of Free School Lunch in the Associations between Family-Environmental Factors and Children’s Fruit and Vegetable Intake in Four European Countries. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vik, F.N.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Øverby, N.C. Free School Meals as an Approach to Reduce Health Inequalities among 10-12- Year-Old Norwegian Children. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineman, A.; Ekwueme, M.C.; Bigayimpunzi, L.; Martin-Daihirou, A.; de Gois V N Rodrigues, E.L.; Etuge, P.; Warner, Y.; Kessler, H.; Mitchell, A. School Meal Programs in Africa: Regional Results from the 2019 Global Survey of School Meal Programs. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 871866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Abe, S.; Zhang, C.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Hernandez, E.; Nozue, M.; Yoon, J. Comparison of the Nutrient-Based Standards for School Lunches among South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, D.; Choi, Y.; Lee, H. Universal Welfare May Be Costly: Evidence from School Meal Programs and Student Fitness in South Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hernandez, M.A.; Deng, G. Large-Scale School Meal Programs and Student Health: Evidence from Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyzy, A.M. School Attendance: Demographic Differences and the Effect of a Primary School Meal Programme in Kyrgyzstan. Educ. Res. Eval. 2019, 25, 381–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlizzi, A.; Delgrossi, M.E.; Cafiero, C. National Food Security Assessment through the Analysis of Food Consumption Data from Household Consumption and Expenditure Surveys: The Case of Brazil’s Pesquisa de Orçamento Familiares 2008/09. Food Policy 2017, 72, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Souza Machado, T.; Cristina Apolinario Borges, C.; Coelho Ribeiro Mendonca, F.; Cristina Euzebio Pereira Dias de Oliveira, B. Parasitological Evaluation of Lettuce Served in School Meals at a Federal State School in Rio DE Janeiro, Brazil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2020, 49, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C. Developments in National Policies for Food and Nutrition Security in Brazil. Dev. Policy Rev. 2009, 27, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, O.; Lee, U.; Kwon, S. Evaluation of Educational School Meal Programs in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. J. Nutr. Health 2017, 50, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, V.; Hore, B. ‘Right Nutrition, Right Values’: The Construction of Food, Youth and Morality in the UK Government 2010–2014. Camb. J. Educ. 2016, 46, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.E.; Gosliner, W.; Olarte, D.A.; Ritchie, L.D.; Schwartz, M.B.; Polacsek, M.; Hecht, C.E.; Hecht, K.; Turner, L.; Patel, A.I.; et al. Universal School Meals during the Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Parent Perceptions from California and Maine. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1561–1579.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, V.; Wittman, H.; Jones, A.D.; Blesh, J. Public Policies for Agricultural Diversification: Implications for Gender Equity. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 718449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, Z.; Cohen, J.F.W.; Sessom-Parks, L.; Lessard, D.; Cooper, M.; Hager, E. Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on School Food Service Revenue: Analysis of Public Local Education Agencies in Maryland. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Le Grand, J. Should the U.S. National School Lunch Program Continue Its In-kind Food Benefit? A School District-level Analysis of Funding Efficiency and Equity. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, R.G.; Gibb, K. Using Economic Analysis to Increase Civic Engagement. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Joo, M. The Effects of Direct Certification in the US National School Lunch Program on Program Participation. J. Soc. Soc. Work. Res. 2020, 11, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kim, Y.; Barnidge, E. Seasonal Difference in National School Lunch Program Participation and Its Impacts on Household Food Security. Health Soc. Work 2016, 41, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Jablonski, B.B.R. Universal Free School Meals: Examining Factors Influencing Adoption of the Community Eligibility Provision. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2024, 47, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Dickson, E. The Exceptions to Child Exceptionalism: Racialised Migrant ‘Deservingness’ and the UK’s Free School Meal Debates. Crit. Soc. Policy 2024, 44, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Nutrition Guidelines and Standards for School Meals: A Report from 33 Low and Middle-Income Countries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Global Child Nutrition Foundation. School Meal Programs Around the World: Report Based on the Global Survey of School Meal Programs; Global Child Nutrition Foundation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’ACqua, F.M. Economic Adjustment and Nutrition Policies: Evaluation of a School-Lunch Programme in Brazil. Food Nutr. Bull. 1991, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spill, M.K.; Trivedi, R.; Thoerig, R.C.; Balalian, A.A.; Schwartz, M.B.; Gundersen, C.; Odoms-Young, A.; Racine, E.F.; Foster, M.J.; Davis, J.S.; et al. Universal Free School Meals and School and Student Outcomes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2424082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity Research in the United States: Where We Have Been and Where We Need to Go. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, I.; Heflin, C. Participation in the National School Lunch Program and Food Security: An Analysis of Transitions into Kindergarten. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 47, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A. Do School Food Programs Improve Child Dietary Quality? Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrestal, S.; Potamites, E.; Guthrie, J.; Paxton, N. Associations among Food Security, School Meal Participation, and Students’ Diet Quality in the First School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.A. Who Feels the Calorie Crunch and When? The Impact of School Meals on Cyclical Food Insecurity. J. Public Econ. 2018, 166, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Barnidge, E.; Kim, Y. Children Receiving Free or Reduced-Price School Lunch Have Higher Food Insufficiency Rates in Summer. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2161–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vik, F.N.; Næss, I.K.; Heslien, K.E.P.; Øverby, N.C. Possible Effects of a Free, Healthy School Meal on Overall Meal Frequency among 10-12-Year-Olds in Norway: The School Meal Project. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, V.R.; Jessiman, P.E.; Breheny, K.; Campbell, R.; Jago, R.; Leonard, N.; Robinson, M.; Strong, S.; Kidger, J. A Mixed Methods, Quasi-Experimental Evaluation Exploring the Impact of a Secondary School Universal Free School Meals Intervention Pilot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirtcheva, D.M.; Powell, L.M. National School Lunch Program Participation and Child Body Weight. East. Econ. J. 2013, 39, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capogrossi, K.; You, W. The Influence of School Nutrition Programs on the Weight of Low-Income Children: A Treatment Effect Analysis. Health Econ. 2017, 26, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hooker, N.H. Childhood Obesity and Schools: Evidence from the National Survey of Children’s Health. J. Sch. Health 2010, 80, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, S.; Gola, A.A. Analyzing the Association between Student Weight Status and School Meal Participation: Evidence from the School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study. Nutrients 2020, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Localio, A.M.; Knox, M.A.; Basu, A.; Lindman, T.; Walkinshaw, L.P.; Jones-Smith, J.C. Universal Free School Meals Policy and Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023063749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holford, A.; Rabe, B. Universal Free School Meals and Children’s Bodyweight. Impacts by Age and Duration of Exposure. J. Health Econ. 2024, 98, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethmann, D.; Cho, J.I. The Impacts of Free School Lunch Policies on Adolescent BMI and Mental Health: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in South Korea. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 18, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-H. Food Preparation for the School Lunch Program and Body Weight of Elementary School Children in Taiwan. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Figlio, D.N.; Winicki, J. Food for Thought: The Effects of School Accountability Plans on School Nutrition. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.D. Why Nutritious Meals Matter in School. Phi Delta Kappan 2020, 102, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrogue, C.; Orlicki, M.E. Do In-School Feeding Programs Have an Impact on Academic Performance and Dropouts? The Case of Public Schools in Argentina. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2013, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, E.; Lau, C. Can the English Baccalaureate Act as an Educational Equaliser? Assess Educ. 2020, 27, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Chen, T.-A. The Contribution of the USDA School Breakfast and Lunch Program Meals to Student Daily Dietary Intake. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Strait, K.; Hildebrand, D.; Amaya, L.; Joyce, J. Variability in Dietary Quality of an Elementary School Lunch Menu with Changes in National School Lunch Program Nutrition Standards. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa064_020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.E.; Sahota, P.; Christian, M.S.; Cocks, K. A Qualitative Study Exploring Pupil and School Staff Perceptions of School Meal Provision in England. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnham, J.C.; Chang, K.; Rauber, F.; Levy, R.B.; Laverty, A.A.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; White, M.; von Hinke, S.; Millett, C.; Vamos, E.P. Evaluating the Impact of the Universal Infant Free School Meal Policy on the Ultra-Processed Food Content of Children’s Lunches in England and Scotland: A Natural Experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Tucker, K.L. Dietary Quality of the US Child and Adolescent Population: Trends from 1999 to 2012 and Associations with the Use of Federal Nutrition Assistance Programs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Schwartz, M.B. Documented Success and Future Potential of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.T.; Widome, R.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N.; Harnack, L.J. Changes in Association between School Foods and Child and Adolescent Dietary Quality during Implementation of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 47, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry-McElrath, Y.M.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D. Foods and Beverages Offered in US Public Secondary Schools through the National School Lunch Program from 2011–2013: Early Evidence of Improved Nutrition and Reduced Disparities. Prev. Med. 2015, 78, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, J.; Odoms-Young, A.; Yaroch, A.L.; Hayman, L.L.; Loiacono, B.; Herman, A.; Fitzgibbon, M.L. Society of Behavioral Medicine Position Statement: Retain School Meal Standards and Healthy School Lunches. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Manore, M.M.; Schuna, J.M., Jr.; Patton-Lopez, M.M.; Branscum, A.; Wong, S.S. Promoting Healthy Diet, Physical Activity, and Life-Skills in High School Athletes: Results from the WAVE Ripples for Change Childhood Obesity Prevention Two-Year Intervention. Nutrients 2018, 10, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gearan, E.C.; Monzella, K.; Gola, A.A.; Figueroa, H. Adolescent Participants in the School Lunch Program Consume More Nutritious Lunches but Their 24-Hour Diets Are Similar to Nonparticipants. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, J.L.; Savaiano, D.A. Effect of School Wellness Policies and the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act on Food-Consumption Behaviors of Students, 2006-2016: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bean, M.K.; Brady Spalding, B.; Theriault, E.; Dransfield, K.-B.; Sova, A.; Dunne Stewart, M. Salad Bars Increased Selection and Decreased Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables 1 Month after Installation in Title I Elementary Schools: A Plate Waste Study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, K.W.; Watson, K.; Zakeri, I.; Ralston, K. Exploring Changes in Middle-School Student Lunch Consumption after Local School Food Service Policy Modifications. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yoder, G.; Lee, N.Y.; Yan, S.; Wolfersteig, W. Racial Disparities in School Lunch Program Participation and Cigarette Use: Evidence from Arizona Youth Survey Data. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.K.; Gearan, E.C.; Schwartz, C. Added Sugars in School Meals and the Diets of School-Age Children. Nutrients 2021, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeratichamroen, A.; Praditsorn, P.; Churak, P.; Srisangwan, N.; Sranacharoenpong, I.; Ponprachanuvut, P.; Chammari, A.; Sranacharoenpong, K.; Chammari, K. Applying the Concept of Thai Nutrient Profiling as a Model for the Thai School Lunch Planner. J. Public Health Dev. 2024, 22, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.; Thorlton, J. Access to Fresh Fruits and Vegetables in School Lunches: A Policy Analysis. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisangwan, N.; Churak, P.; Praditsorn, P.; Ponprachanuvut, P.; Keeratichamroen, A.; Chammari, K.; Sranacharoenpong, K. Using SWOT Analysis to Create Strategies for Solving Problems in Implementing School Lunch Programs in Thailand. J. Health Res. 2023, 37, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, S.; Acciai, F.; Au, L.E.; Yedidia, M.J.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P. Parental Perceptions of the Nutritional Quality of School Meals and Student Meal Participation: Before and after the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronitawati, P.; Setiawan, B.; Sinaga, T. The Influence of Nutritionist-Based Food Service Delivery System on Food and Nutrient Quality of School Lunch Program in Primary Schools in Indonesia. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2020, 66, S450–S455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajbhandari-Thapa, J.; Bennett, A.; Keong, F.; Palmer, W.; Hardy, T.; Welsh, J. Effect of the Strong4Life School Nutrition Program on Cafeterias and on Manager and Staff Member Knowledge and Practice, Georgia, 2015. Public Health Rep. 2017, 132, 48S–56S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, O.; Lee, Y. Effects of Students’ Satisfaction with School Meal Programs on School Happiness in South Korea. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2018, 12, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, M.M. The Right to Taste: Conceptualizing the Nourishing Potential of School Lunch. Food Foodways 2018, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.; Dundas, R.; Torsney, B. School and Local Authority Characteristics Associated with Take-up of Free School Meals in Scottish Secondary Schools, 2014. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption by School Lunch Participants: Implications for the Success of New Nutrition Standards; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peckham, J.G.; Kropp, J.D.; Mroz, T.A.; Haley-Zitlin, V.; Granberg, E.M.; Hawthorne, N. Socioeconomic and Demographic Determinants of the Nutritional Content of National School Lunch Program Entrée Selections. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-Y.; List, J.A.; Samek, A. Got Milk? Using Nudges to Reduce Consumption of Added Sugar. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, R.; Read, M.; Henderson, K.E.; Schwartz, M.B. Removing Competitive Foods v. Nudging and Marketing School Meals: A Pilot Study in High-School Cafeterias. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, A.; Yin, L.; O’Sullivan, B.; Ruetz, A.T. Historical Lessons for Canada’s Emerging National School Food Policy: An Opportunity to Improve Child Health. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusser, W.M.; Cumberland, W.G.; Browdy, B.L.; Lange, L.; Neumann, C. A School Salad Bar Increases Frequency of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among Children Living in Low-Income Households. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, J.M.; Harris, K.; Mailey, E.L.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Rosenkranz, S.K. Acceptability and Feasibility of Best Practice School Lunches by Elementary School-Aged Children in a Serve Setting: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabas, L. The School Food Plan: Putting Food at the Heart of the School Day. Nutr. Bull. 2014, 39, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.E.; Cohen, J.; Canterberry, M.; Carton, T.W. Factors Associated with School Lunch Consumption: Reverse Recess and School “Brunch”. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.L.; McKee, S.L.; Burkholder, K.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Schwartz, M.B. USDA’s Summer Meals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Participants and Non-Participants in 2021. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 495–508.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.N.; Soldavini, J.; Grover, K.; Jilcott Pitts, S.; Martin, S.L.; Thayer, L.; Ammerman, A.S.; Lane, H.G. “let’s Use This Mess to Our Advantage”: Calls to Action to Optimize School Nutrition Program beyond the Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petchoo, J.; Kaewchutima, N.; Tangsuphoom, N. Nutritional Quality of Lunch Meals and Plate Waste in School Lunch Programme in Southern Thailand. J. Nutr. Sci. 2022, 11, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Gao, R.; Bawuerjiang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Cai, M. Food and Nutrients Intake in the School Lunch Program among School Children in Shanghai, China. Nutrients 2017, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishdorj, A.; Capps, O., Jr.; Murano, P.S. Nutrient Density and the Cost of Vegetables from Elementary School Lunches. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 254S–260S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaki, S.F.; Moore, C.E.; Chen, T.-A.; Weber Cullen, K. Younger Elementary School Students Waste More School Lunch Foods than Older Elementary School Students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, J.G.; Kropp, J.D.; Mroz, T.A.; Haley-Zitlin, V.; Granberg, E.M. Selection and Consumption of Lunches by National School Lunch Program Participants. Appetite 2019, 133, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.L.; Brady, P.; Askelson, N.; Ryan, G.; Delger, P.; Scheidel, C. What Do Parents Think about School Meals? An Exploratory Study of Rural Middle School Parents’ Perceptions. J. Sch. Nurs. 2022, 38, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.W.; Kesack, A.; Daly, T.P.; Elnakib, S.A.; Hager, E.; Hahn, S.; Hamlin, D.; Hill, A.; Lehmann, A.; Lurie, P.; et al. Competitive Foods’ Nutritional Quality and Compliance with Smart Snacks Standards: An Analysis of a National Sample of U.s. Middle and High Schools. Nutrients 2024, 16, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, J.; Amevinya, G.S.; Holdsworth, M.; Savy, M.; Laar, A. Nutritional Quality and Diversity in Ghana’s School Feeding Programme: A Mixed-Methods Exploration through Caterer Interviews in the Greater Accra Region. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Power, E.; Holland, M.R. Canada’s Missed Opportunity to Implement Publicly Funded School Meal Programs in the 1940s. Crit. Public Health 2020, 30, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boling, P.; Blackburn, E.; Paine, J.; Smith, R. Farm-to-School in Indiana: The Local Politics of Feeding Children. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calancie, L.; Soldavini, J.; Dawson-McClure, S. Partnering to Strengthen School Meals Programs in a Southeastern School District. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2018, 12, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleef, E.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Seidell, J.; Vingerhoeds, M.H.; Polet, I.A.; Zeinstra, G.G. Which Factors Promote and Prohibit Successful Implementation and Normalization of a Healthy School Lunch Program at Primary Schools in the Netherlands? J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2022, 41, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Indonesia’s Strategic Development Initiatives. Mengkaji Ulang Program Makan Bergizi Gratis Makan Bergizi Gratis: Menilik Tujuan, Anggaran Dan Tata Kelola Program; CISDI: Central Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Juliannisa, I.A.; Rahma, H.; Mulatsih, S.; Fauzi, A. Regional Vulnerability to Food Insecurity: The Case of Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Purpose | Country |

|---|---|

| Improve children’s health and nutrition | Africa, China, Kyrgyzstan |

| Improve healthier meal choices | UK, South Korea |

| Reduce socioeconomic disparities | Africa, U.S. |

| Agricultural objectives | Africa, Brazil |

| Addressing food insecurity | U.S. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abadi, M.N.P.; Basrowi, R.W.; Gunawan, W.B.; Arasy, M.P.; Nurjihan, F.; Sundjaya, T.; Pratiwi, D.; Hardinsyah, H.; Astuti Taslim, N.; Nurkolis, F. Unraveling Future Trends in Free School Lunch and Nutrition: Global Insights for Indonesia from Bibliometric Approach and Critical Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172777

Abadi MNP, Basrowi RW, Gunawan WB, Arasy MP, Nurjihan F, Sundjaya T, Pratiwi D, Hardinsyah H, Astuti Taslim N, Nurkolis F. Unraveling Future Trends in Free School Lunch and Nutrition: Global Insights for Indonesia from Bibliometric Approach and Critical Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(17):2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172777

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbadi, Muhammad Naufal Putra, Ray Wagiu Basrowi, William Ben Gunawan, Mutiara Putri Arasy, Felasiana Nurjihan, Tonny Sundjaya, Dessy Pratiwi, Hardinsyah Hardinsyah, Nurpudji Astuti Taslim, and Fahrul Nurkolis. 2025. "Unraveling Future Trends in Free School Lunch and Nutrition: Global Insights for Indonesia from Bibliometric Approach and Critical Review" Nutrients 17, no. 17: 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172777

APA StyleAbadi, M. N. P., Basrowi, R. W., Gunawan, W. B., Arasy, M. P., Nurjihan, F., Sundjaya, T., Pratiwi, D., Hardinsyah, H., Astuti Taslim, N., & Nurkolis, F. (2025). Unraveling Future Trends in Free School Lunch and Nutrition: Global Insights for Indonesia from Bibliometric Approach and Critical Review. Nutrients, 17(17), 2777. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172777