Abstract

Soy has a long history of consumption in Asia and was traditionally prepared by rinsing, cooking, and simmering, methods which remove estrogenic isoflavones (Isofls). Population studies have indicated that soy and/or Isofls may be associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer (BC), while in vitro and experimental data indicate dose-related proliferative effects of Isofls on breast cells. This review attempts to decipher the role of soy and Isofls in the risk of BC in women, since previous studies have suggested a lack of association with BC. Several dozen population studies conducted in Asian and Western countries were analyzed, as were data collected during in vitro animal and clinical trials of relevant doses of soy and Isofls. Although soy intake has been estimated well in Asian countries and could be related to preventive effects on BC risk, this has not been the case in the West, where the consumption of hidden soy is often omitted. However, in both cultures, the Isofl intake is misestimated, and the groups are misclassified. Indeed, in Asia, the origin of soy foods, i.e., homemade or industrial, has never been reported, and in the West, the amount of Isofls consumed in hidden soy has not been determined. Moreover, in most cohort studies, only a few subjects were exposed to active doses of Isofls on breast cells. Similarly, clinical interventions showed estrogenic effects of Isofls at relevant doses. Finally, population studies have not shown any convincing link between soy or Isofl intake and BC risk, likely because they have opposite effects on this pathology. Thus, based on in vitro, experimental, and clinical data, a deleterious effect of Isofls cannot be excluded when active doses are ingested, even if the soy food matrix can be protective.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a critical public health problem worldwide [1]. It is the second most common cancer diagnosed and a leading cause of death in women [1]. The reality of BC is complex [2,3,4], with some tumors sensitive to estrogens and expressing ERα and/or ERβ [2] and others expressing HER2, an epithelial growth factor [3], while others are classified as triple-negative BC (TNBC) [4]. TNBC comprises a variety of cancers, some of which can respond to estrogens and xenoestrogens via a transmembrane receptor—the G-Protein coupled Estrogen Receptor (GPER). The affinity of this last receptor for Isofls and several drugs used in BC management, such as tamoxifen or fulvestran, may lead to a multidrug-resistant pattern that makes treatment particularly difficult [5].

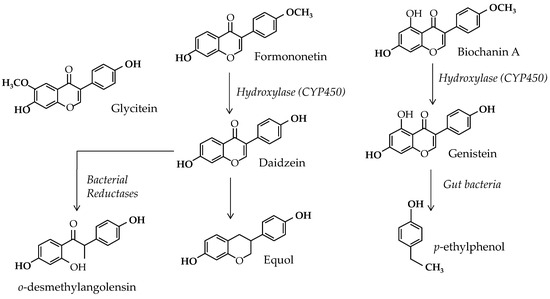

In this context, some authors continue to seek natural preventive or curative treatments and debate the potential effect of herbal medicines or functional foods to reduce BC risk [6]. The potential role of soy and Isofls in estrogen-dependent BC is part of this debate. Soy Isofls are weak estrogenic polyphenols belonging to the flavonoid family present in legumes, where they exert several crucial effects. Indeed, they have been shown to attract symbiotic organisms: rhizobium bacteria and mycorrhizae fungi [7]. These partners form nodules on legume roots that enable atmospheric nitrogen fixation and high-level protein synthesis [8]. These Isofls are also known to act as alert substances when the plant is attacked by pests [9]. Soy contains three types of Isofls, i.e., genistein, daidzein, and glycitein, but these substances can be obtained from precursors present in several clover species and alfalfa. They can also be transformed into active—equol—and inactive—o-desmethylangolensin and p-ethylphenol—metabolites by the gut microflora. The Isofls and their parent compounds are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Soy isoflavones and parent compounds, with metabolic links between them.

The effect of estrogenic Isofls on BC is still a subject of controversy. Indeed, results obtained from biological studies show discrepancies, in which some effects are beneficial, while others are deleterious [10]. Questions remain because in human populations, Isofls are associated with soy consumption [11]. Indeed, soy was shown to contain other substances that potentially prevent BC [12] and is usually consumed in a context where other BC inductors are reduced [13]. In addition, this legume is associated with traditional diets in Asia [14] and with a healthy diet in Western countries [15]. Therefore, confounding factors could bias the effects of both the food and the nutrient, as well as the interpretation of the results.

Indeed, it was recently determined that traditional and domestic Asian cooking methods can reduce Isofls in soy foods [16] thanks to basic water treatments. This reduction mainly occurs when soy is prepared at home by following family recipes. Population studies in Asian countries may miss this context when attempting to show the effect of soy and Isofls on health issues. In fact, in these studies, the estimation of exposure to Isofls is usually calculated from Isofl concentrations measured in industrially prepared soy foods obtained in marketplaces [17]. Worse, in some cases, the database used lacks values obtained from local soy foods [18]. At any rate, in these circumstances, the commercial soy foods were prepared at a large scale, with reduced water treatments. Consequently, these commercially available soy foods are most likely to contain higher amounts of Isofls than homemade soy foods. Since the food frequency questionnaires used in population studies usually do not assess the origin of the soy foods eaten by the participants, the estimated Isofl intake may be biased.

To resolve this problem, this review examines available relevant data on the roles of soy and Isofls in BC. The aim is to clarify the effects of soy and Isofls on BC risk.

2. Isoflavones and Breast Cancer In Vitro

2.1. Different Types of Breast Cancers

In vitro cell models are simplified systems that cannot always be superimposed on the in vivo situation. Many different types of BC can only be identified via specific target cells, i.e., canal, lobular, basal, and parenchymal cells [19]. Some are invasive and induce metastasis. These cancers are also characterized by many different receptor expressions. Among the crucial receptors presently considered in clinical approaches are the canonical estradiol receptors (ERs), from which tumors are then identified as being either ER+ or ER−. However, ER+ tumors can express various proportions of the two estradiol receptor forms: ERα and ERβ. While such a detailed description is not always assessed, it could be crucial since xenobiotics may have different affinities for these two receptors [20]. Indeed, Isofls have a higher affinity for ERβ. Additionally, these forms can be present at the nucleus in an active form, in the cytoplasm as a reserve form, or below the cell membrane as forms involved in rapid cell signaling [21]. Several isoforms of both ERs obtained by alternative splicing during transcriptional steps also exist. They can induce different reactions to xenobiotics depending on their resulting ligand binding abilities and the conformation of their activation functions [22]. The detection of PRs (both PR-A and PR-B) is also a clinical characteristic of breast tumors, since PR synthesis is under the control of an ER−-dependent transcriptional activity [23]. Therefore, a breast tumor can be identified as PR+ or PR− based on its ability to express these receptors. Note that in normal cells, the proportions of PR-A and PR-B are usually equal and that a significant imbalance is usually observed in tumor cells [24]. In addition, HER2 is also considered in clinical classification, as it is a growth factor receptor that worsens the prognosis of BC [25]. Again, clinical classification considers tumors that can be either HER2+ or HER2−. Finally, another estrogen receptor has been found in almost all BC cells, including in TNBC. It is called GPER and is a transmembrane estrogen receptor that is expressed in specific conditions in vitro [26]. For the moment, GPER is not clinically diagnosed, although it may be involved in several resistance pattern to various drugs [27]. Furthermore, in vitro, there seems to be two distinct pathways activated via GPER. At low doses, estradiol (E2) and other estrogens stimulate the EGFR-dependent pathway, inducing cell growth, but at high doses, ≥1 µM, they induce a cAMP-dependent pathway preferentially involved in cell apoptosis. The ligand-binding domain of GPER is large and can be filled with two molecules. It is likely that the GPER conformation differs depending on whether one or two ligands are bound to the binding domain. This may explain why the response via GPER is different according to the availability of the ligands. Isofls from soy have been shown to bind to ERα, ERβ [28], and GPER [29] at doses that can be achieved in vivo.

2.2. Methodological Limits of In Vitro Studies

2.2.1. Doses Tested

In vitro, cells are in survival conditions. They usually lack the main cell interactions that exist in vivo and are maintained in simple media that often lack the basic factors existing in vivo. More important, they are often submitted to doses of hormones, drugs, or xenobiotics that are very different from those existing in vivo. Indeed, if E2 is usually tested in the pM range, which is the normal range of concentrations in pre-menopausal women, other substances can be tested at pharmacological concentrations that are much higher than those occurring in vivo. This is often the case for Isofls. Indeed, several studies on the pharmacokinetics of Isofls [30,31] or the disposition of these compounds in breast tissue [32,33] showed that their concentrations are in the nM range and, at the very best, around 1 µM. These doses correspond to the sum of conjugated and aglycone substances, and the aglycones only represent 1/10 of the total Isofls [31]. At these doses, their effects can be either estrogenic or null. However, many studies looking for protective effects of Isofls on BC were and are still performed at doses from 10 to 500 µM [34,35]. Indeed, the scientists who used these doses probably assumed that the higher the dose, the more pronounced the effect. However, this assumption is wrong. Looking closer at the cell machinery, the signalization pathway has been found to depend on the dose of endocrine disruptor used [35]. Indeed, genistein from soy is known to be an inhibitor of tyrosine kinase, with an IC50 at 20 µM [36]. It was sold by chemical providers as a specific inhibitor of tyrosine kinase until the end of the 1990s. Since many intracellular pathways involve tyrosine kinase activity, it is not surprising to find that genistein at doses over 10 µM inhibits cell growth, and this effect has nothing to do with an estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effect. In this review, we will only consider works performed with physiologically relevant doses, and thus, always <5 µM.

2.2.2. Forms and Cocktails

Some studies have dealt with the estrogenic potency of soy or other legume extracts directly tested in vitro. The system used was either a yeast system transfected with basic estrogen receptor machinery [37] or a cell model. In some cases, several enzymatic reactions were preserved, such as in hepatocyte cultures [38], but in others, the cells were models for breast tissues [39]. Although such tests are used in pharmacology as a first screening step to check for the presence of active compounds in herbal preparations, they have numerous limits, one of which is linked to plant physiology. Indeed, in plants, the active compounds may not be in metabolic forms equivalent to those found in human consumers. Hence, in soy matter, Isofls are essentially in conjugated forms, i.e., glucosides, acetyl, or malonyl forms, which are all soluble in water. However, an extract is only a part of a plant, and its composition essentially depends on the solvent used for the extraction. If this solvent is organic and not edible, there is a risk that the extract will not reproduce what is absorbed during oral intake. Additionally, during the ingestion process, the gut and the liver sort the different substances of a mixture. As a result, the substances present in the blood are not in the same forms nor in the same proportions as in the plant. If there are different substances in an extract and if these substances do not have the same effect in a basic test, then their results could not be used to explain the in vivo situation in humans. Finally, extracts can be tested at pharmacological concentrations that are far from being reproducible in vivo. Therefore, in vitro tests performed with plant extracts have only indicative values and cannot be extrapolated to the in vivo situation.

As already mentioned, Isofls such as E2 are mainly present in the blood and lymph as well as breast tissue in conjugated forms. These are glucurono- and/or sulfo-conjugated Isofls that are physicochemically unable to enter a cell. This explains why the distribution volume of Isofls is low in animals and humans [40]. It is thought that some cell types, including hepatocytes, can free the aglycone forms in vitro [41], but this remains disputed for other cell lines, including breast cells. Indeed, the ability of a cell line to free xenoestrogens from their conjugating residues would be crucial to be considered in cell specificity approaches [42].

Additionally, after soy intake, many substances can reach a breast cell. This includes the three main Isofls from soy, i.e., genistein, daidzein, and glycitein, as well as the metabolites equol and o-desmethylangolensin. All these substances are of course under aglycone and mainly under conjugated forms. Therefore, before considering the effect of Isofls on BC cells in vitro, it should be remembered that they are cocktails of substances that reach the cells in vivo and that these cocktails can also include E2 and its other estrogenic metabolites, i.e., estrone (E1), estriol (E3), or estetrol (E4). Finally, eating soy food also results in the digestion of other substances such as saponins and sapogenins, carbohydrates, fibers, peptides, enzymes, complex polyphenols like tannins, phytic acids, minerals, and vitamins that can induce complex responses from the gut and interfere directly or via secondary messengers with target cell functioning.

2.3. Summary of Isoflavone Effects In Vitro on Breast Cancer Cells

The in vitro approach is the most convenient in many cases since it is easily affordable to many scientific teams. Thus, many data are available nowadays on these models, and in many cases, these studies were performed using high doses of Isofls and showed pro-apoptotic effects on BC cells. These studies were designed to explain the seemingly protective effect of soy and Isofl consumption in Asian populations on BC [43]. Although this protective effect will be analyzed later on in this review, scientists have looked for substantial arguments to explain how estrogenic substances could prevent estrogen-dependent diseases. The first approach dealt with a competitive process between the native E2 and the xenoestrogens from soy. In vitro, specific proportions of both E2 and Isofls were found, and they showed an inhibiting effect of the weak plant estrogens on the native E2 [44]. However, this phenomenon occurred when the proportions of E2 and Isofls reached a perfect balance, which depended on the relative affinities of the two types of substances with the ERs. Such a proportion could be maintained in vitro, but in vivo, both Isofl and E2 concentrations fluctuate with time [45,46]. Therefore, the relevant balance between the two types of compounds can only be achieved transiently. In addition, the mechanisms that were involved in BC prevention by high doses of Isofl were numerous. They dealt with antioxidant properties, anti-tyrosine and anti-protein kinase effects, Bcl-2 inhibition, Akt signaling inhibition, anti-angiogenic effects, anti-DNA topoisomerase effects, and NF-κB downregulation [47,48]. More recently, epigenetic footprints were observed at doses of genistein > 50 µM and daidzein > 100 µM [49]. All these effects cannot be achieved in vivo since Isofl concentrations, by the target cells, only reach 2 µM in exceptional conditions. Thus, we will not focus on them. Table 1 below shows the effect of soy Isofls in vitro when tested at physiologically relevant concentrations.

Table 1.

Effects of soy isoflavones on breast cancer cells in vitro.

Table 1 mainly shows that Isofls in aglycone forms and at physiological doses can induce cell growth or have no effect on cell proliferation. This depends on the availability of estrogen receptors. At doses achievable dietarily, they do not induce cell apoptosis or reduce BC cell proliferation.

3. Soy or Isoflavones and Breast Cancers in Animals

3.1. Toxicological Studies

As mentioned previously, soy Isofls undergo complex metabolism after ingestion, and this affects their forms and concentrations in blood, lymph, and cell environments. Thus, it could be helpful to develop BC cell cultures stimulated by plasma or lymph basic extracts [56]. However, to more accurately represent the human in vivo situation, tests can also be developed in animal models. In these cases, it is crucial to respect oral exposure to Isofls, since other routes can shunt metabolic reactions and deeply impair models’ metabolome [57]. The main limit of animal models is that they have their own metabolism. Indeed, rats, mice, monkeys, and pigs have different gut and liver enzymes, and this affects the resulting composition of the biological fluids that reach mammary cells in vivo [58]. Considering soy Isofls, one of the main differences between animal models and human beings is the ability of their gut flora to produce equol [5]. Indeed, rodents and monkeys are all equol producers, while only a portion of humans and pigs harbor the competent bacteria [58,59]. Moreover, the ability of liver enzymes to produce glucurono- and sulfo-conjugates of Isofls is not the same in rodents, non-human primates, pigs, or humans [58,59]. Although the conjugates are all considered to be ineffective, the proportion of aglycone forms directly impact the estrogenic potency of the Isofl in the different models [58,59]. Nevertheless, after an oral challenge, the microenvironment of BC cells is closer to that of human consumers than that in in vitro cell culture media.

3.1.1. Official Toxicological Studies

In 2008, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) of the USA published a comprehensive multigenerational, 2-year dietary study on the potential carcinogenic effect of genistein, one of the main forms of dietary soy Isofls [60]. The study was performed on Sprague Dawley rats and started during the gestation of dams. The dietary exposure concentrations were 0, 5, 100, and 500 ppm and led to serum genistein levels possibly occurring in human consumers. The ingestion rate was calculated for the animals at different periods of life. It was found to be 0, 0.5, 9, or 45 mg/kg body weight per day during female pregnancy and 0, 0.7, 15, or 75 mg/kg bw/day during lactation. A minimal transfer of genistein to pups was observed via the dams’ milk and after weaning; the exposure of animals prior to postnatal day (PND) 140 was approximately 0.4, 8, or 44 mg/kg bw/day for females and 0.4, 7, or 37 mg/kg bw/day for males. For the period between PND140 and the end of the study, mean ingested doses were approximately 0.3, 5, or 29 mg/kg bw/day for females and 0.2, 4, or 20 mg/kg bw/day for males. The study included three exposure arms:

- Continuous exposure from conception through the 2 years, designated F(1)C;

- Exposure from conception through PND 140 (20 weeks), followed by a control diet until 2 years, designated F(1)T140;

- Exposure from conception through weaning (PND 21), followed by a control diet until 2 years, designated F(3)T21. The animals of this group were a third generation of animals exposed to genistein from F0 pregnancy and issued from the multigenerational reproductive toxicology study of NTP USA [61].

For the study, 50 animals per sex were assigned to each exposure group in each arm of the study. Animals of the control groups that were moribund or that died prematurely were sampled for histopathology, and the observations were included in the study. The study showed that the survival was similar in all groups, ranging from 62 to 86% for males and 43 to 64% for females.

The mean body weights of 500 ppm F(1)C females and F(1)T140 animals were always lower than that of the control group. Females of the F(1)C, F(1)T140, and F(3)T21 groups fed 500 ppm genistein all showed the early onset of aberrant estrous cycles, suggesting early reproductive senescence. These phenomena were also observed in the F(3)T21 females at 5 and 100 ppm genistein. Pituitary gland weights were significantly increased in females of the F(1)C and F(1)T140 groups fed 500 ppm genistein, as was also the case in the females of the F(3)T21 group fed 100 ppm genistein. In F(1)C females, there was a significant positive trend in the incidences of mammary gland adenoma or adenocarcinoma with genistein doses. Moreover, the incidence of mammary gland adenoma or adenocarcinoma was significantly greater in the 500 ppm genistein-fed group than in the controls. Parallelly, the incidence of benign mammary fibroadenoma tended to decline with genistein doses in F(1)C females, and it was significantly reduced in the 500 ppm group compared with the controls. In F(1)T140 females fed 5 and 100 ppm genistein, the combined incidences of adenoma and adenocarcinoma tended to be reduced compared with the control or to the groups fed 500 ppm genistein. A positive trend was observed in the incidences of mammary adenoma or adenocarcinoma in F(3)T21 females. There were positive trends in the incidences of adenoma or carcinoma in the pars distalis of the pituitary gland of females in the F(1)C and F(1)T140 arms. The pars distalis contains the gonadotropic cells controlling reproductive cycles. Moreover, in the F(1)C group, the incidence of these adenomas or carcinomas of the pituitary gland was greater in the 500 ppm group than in the controls.

In F(1)C males, the incidences of combined adenoma or carcinoma of the pancreatic islets significantly increased dose-dependently, but this incidence was not significant in the 500 ppm group compared with the control group. Additionally, there was no evidence of a carcinogenic effect of 5, 100, or 500 ppm genistein in male Sprague Dawley rats exposed continuously for 2 years, from in utero life until PND140, or for the third generation from in utero life to weaning.

However, in female Sprague Dawley rats continuously exposed to genistein for 2 years, there was some evidence of carcinogenic activity of genistein based on an increased incidence of mammary adenoma or adenocarcinoma and pituitary neoplasms. In parallel, in these females, there was a significantly reduced incidence of benign mammary gland fibroadenoma when female rats were fed 500 ppm genistein. In female Sprague Dawley rats exposed to genistein from conception through to PND140 and then to a control diet until euthanasia, there was equivocal evidence of carcinogenic effect based on increased incidences of pituitary gland neoplasms. In female F(3)T21 offspring, issued from three prior generations of animals treated with genistein and exposed from conception through weaning to Isofls before shifting for 2 years to a control diet, there was equivocal evidence of carcinogenic activity of genistein based on increased incidences of mammary adenoma or adenocarcinoma. Exposure to genistein also accelerated the onset of aberrant estrous cycles in all female Sprague Dawley rats fed 500 ppm genistein.

The effects of genistein on estrous cycling and the incidences of common hormonally related spontaneous neoplasms of female Sprague Dawley rats were consistent with an estrogenic mechanism of toxicity. The study, which followed the OECD procedures, clearly indicated that genistein and its blood metabolites could induce mammary tumors after long-term continuous exposure to dietary achievable doses of genistein. Such an effect is carcinogenic and not only growth-promoting. As a result, considering the reliability of this toxicity evaluation, it can be said that genistein may not be safe for the mammary gland. This is true for continuous exposure to a diet containing significant amounts of genistein.

3.1.2. Studies Involving Tumorigenic Substances

The previous paragraph illustrates the ability of genistein to induce carcinoma and adenocarcinoma de novo. However, based on population studies, the question may also be to determine if Isofls from soy can or cannot prevent the tumorization process from normal cells to tumor cells in vivo. To answer this question, experimental carcinomas were induced and the effects of Isofl or soy extracts on this process were analyzed. In these cases, the recorded effects concerned the ability of the Isofl to prevent or accelerate the early cancerous process, while a proliferative effect would only indicate a growing effect on already-tumoral cells. Experiments have been performed by numerous scientists to date involving either purified Isofls, extracts enriched in Isofls, or soy proteins and even soy foods such as soy milk. The previous authors tended to answer several different questions. In some cases, they tried to determine a preventive effect, and soy or Isofl treatments were performed or started before the chemically induced cancerization. On the contrary, they could also try to determine if soy or Isofls could inhibit tumorization once the process was already induced. The following tables gather data already published so far. To try to homogenize these data with those of the USA NTP, the doses tested are expressed in mg/kg bw/day, and the plasma levels were estimated as accurately as possible. Table 2 gathers studies where soy or Isofls were administrated prior to carcinogenic treatment. In all cases, only studies dealing with oral exposure were considered to integrate the metabolic reactions occurring in the digestive tract.

Table 2.

Summary of studies on the oral administration of soy and/or soy isoflavones to rats prior to the chemical induction of mammary tumorigenesis.

From Table 2, it seems that low doses of genistein (1 to 25 mg/kg bw/day), given orally to dams’ nursing pups, would protect these pups during their adult life, even if according to [60], the genistein amounts transferred to pups was very low. This was seen via a lower incidence of mammary tumors in pups exposed in utero and neonatally until weaning. At higher doses (28 to 40 mg/kg bw/day), no effects were recorded. Additionally, the inhibition seemed significant only if the animals were followed for more than 20 weeks. After weaning but prior to DMBA, genistein had no effect or seemed to activate tumorization. Equol was not efficient when given orally and neonatally and until PND35. The effects of soy protein or a soy diet were not so clear. According to [65], gestational and neonatal exposure to low doses of genistein may induce early differentiation of the mammary tissue, which played a role against the tumorization process induced by DMBA. However, these experiments did not exclude a potential effect of Isofls on the bioavailability of DMBA nor an epigenetic effect on mammary cells preventing the synthesis of an oncogene such as MDM2, which is produced under DMBA treatment [77,78].

Table 3 gathers data obtained when soy or Isofls were administrated after the carcinogen.

Table 3.

Summary of studies on the oral administration of soy and/or soy isoflavones to rats mainly after the chemical induction of mammary tumorigenesis.

Again, Table 3 only gathers data obtained on rats fed known amounts of Isofls. One study by Gotoh et al. [85] reported a preventive effect of soy protein; miso; and biochanin A, a metabolic precursor of genistein, on MNU-induced mammary tumors, but the amount of Isofls could not be determined. Thus, the study does not appear in Table 3. Looking at the results presented in this table globally, the effects of Isofls or soy only administrated after the cancerogenic substances were not so clear. Hence, the study from Lamartiniere [65], which included a first exposure before the DMBA treatment, showed an inhibitory effect. Similarly, the study by Liu et al. [82] showed a slight inhibitory effect with Isofls delivered after DMBA, but only for a 3-week duration. Equally, a study from Ma et al. [83] conducted with high doses of a soy extract showed an inhibitory effect. In that case, at least two hypotheses could be made to explain these results: (1) the effects were linked to the doses used, and (2) the soy extract contained other substances that could be involved in the tumors’ regression [86]. However, the precise composition of the soy extract was not disclosed in the study, and therefore, it was difficult to determine what could be responsible for the inhibitory effect recorded.

Finally, it appears that only neonatal exposure to relatively low levels of genistein, i.e., those present in dams’ milk, would be able to counter the tumorization process induced by the cancerogenic compound DMBA [65]. Such an effect is observed later in a rat’s life and may involve the epigenetic regulation of either oncogenic or anti-oncogenic genes [87]. According to [88,89], a first explanation would be that early exposure to lactational genistein would enhance the maturation of the mammary gland in female pups, and this maturation process, dealing with mammary cell differentiation, would counteract the de-differentiation process involved in cell tumorization. Because the development stages of rats are different from those of humans, it is difficult to determine the equivalent period in humans’ lives. Indeed, rat exposure did not mimic the one produced by soy-based infant formula [61].

3.2. Humanized Rodent Models

Most studies performed on humanized rodent models were performed on athymic nude mice implanted with human BC cell lines. Such tests allow the human cells to be in contact with circulating forms of Isofls, although some differences can exist between the human and rodent situations in terms of concentrations, proportions of conjugates and aglycones, and proportions of sulfates and glucuronides [59]. At the very least, models can show that these circulating forms could be active. Provided that the tests were performed at dosages inducing relevant concentrations for human beings, they can be informative. Indeed, Isofl plasma levels were recently assayed in French women, including a subject consuming soy products several times a day [90]. The median and max levels of Isofl in these plasmas were 0.135 μM for genistein and 0.097 μM for daidzein in the general population and 1.73 μM of genistein and 0.99 μM of daidzein in the high-soy consumer. This means that a 2.62 µM concentration of total Isofls (including conjugated phytoestrogens) in plasma is achievable in the blood of soy-eating women. However, it is not possible to strictly derive a dose effect from the rodent model to human beings because the animal is immunodeficient. Indeed, it is well known that the immune system is crucial in the management of cancer cells [91]. Therefore, the model indicates a way of effect progression but not an efficient dose. Despite all these limits, it seemed important to check for the responses of such humanized models in the following table. Hence, Table 4 gathers only data obtained following oral route administration on mice models fed either soy extracts or Isofls, where doses were homogenized for comparisons, and on estrogen-dependent cancer cell lines only.

Table 4.

Summary of the effect of oral isoflavones on athymic nude mice implanted with estrogen-dependent human breast cancer cells.

Table 4 clearly shows that genistein and possibly daidzein in circulating forms could enhance the proliferation of human estrogen-dependent BC cells of the MCF-7 type at plasma doses ≥ 0.7 µM for genistein and ≥0.9 µM for daidzein [92,93,94,95,99,100,103,105,107]. The plasma levels, when available, help in comparing experiments with each other but cannot really help in defining an active dose for human beings. The results also indicated a negative interaction of two drugs classically used to treat estrogen-dependent BC in women, i.e., tamoxifen (TAM), an anti-estrogen, and letrozole, an anti-aromatase [55,96,102]. The effects were not observed for all athymic mice strains. The proliferation effect seemed to require a minimum duration of treatment, i.e., 15 weeks. When the duration was shorter, there was either no effect recorded or an inhibition of proliferation [101,106]. Some studies orally delivered pure compounds, either aglycones or in conjugated forms, but others tested more complex soy matrices containing small amounts of glycitein, a pure ERβ agonist, saponins, or peptides such as lunasin. When using soy matrices, the results were less clear and typically depended on the dosage of genistein and daidzein [97,98,103,105]. This did not exclude the action of other soy components, since the action of soy may result from an interaction of different molecules in an optimal proportion. Although in vitro the daidzein metabolite equol can induce cell proliferation, such a result was not observed on the athymic mice model [107]. Equol potentiated the action of genistein but had no effect per se. However, mice are universal equol producers; thus, when daidzein and soy matrices were tested, equol and its conjugates were present in the animals’ blood and in the cell vicinity.

Besides these tests involving estrogen-responsive BC cells, some experiments were performed on estrogen-non-responsive cells and, essentially, TNBC. A compilation of the main results is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of the effect of oral isoflavones on athymic nude mice implanted with estrogen-independent human BC cells.

Table 5 clearly shows that Isofls from soybean did not stimulate TNBC cells in athymic mice models. This effect may be in conflict with the activation phenomenon sometimes recorded in vitro with Isofls on TNBC. These were obtained via the EGFR-dependent pathway activated by GPER [51]. However, this stimulation pathway seems only to occur at low Isofl doses and GPER expression may not always occur at a sufficient level in implanted cells to exhibit any significant effect. Hence, for the moment, in vivo studies involving athymic mice and dealing with GPER pathways are still scarce [112]. They have been performed on mice implanted with SKBR3 cells.

3.3. Other Animal Models

3.3.1. Sow, Gilts, and Piglets

As mentioned earlier, rodents may not always be considered the best models for the human transposition of physiological effects. They may differ from humans essentially in terms of metabolic issues that play a role in xenobiotics’ bioavailability and actions. Regarding equol production, as well as conjugation reactions, pigs may be considered closer to humans than rodents. Unfortunately, there is little data on the effects of soy and/or Isofls on the mammary gland in this species. According to Ford et al. [113], genistein at doses ranging from 50 to 400 mg/day in i.m. injections, exerted an estrogenic effect on gilts, as observed on tissue modifications of the utero-vaginal tract. In [114], it was shown that these i.m. treatments led to genistein plasma concentrations below 1.4 µM. Such a dose was in the range of those tested in rodent models and plausibly occurring in the plasma of human soy consumers. Additionally, the oral treatment of gilts with 2.3 g genistein/day for 93 days significantly induced mammary parenchymal cell hyperplasia [115]. In the study, genistein plasma levels were about 0.63 µM, while daidzein plasma levels were about 0.33 µM. Finally, the feeding of female neonate piglets with soy-based infant formula containing high amounts of Isofls induced the expression of mammary genes involved in cell proliferation [116]. The formula led to genistein plasma levels close to 2 µM and daidzein plasma levels close to 1.3 µM. These plasma concentrations are in the same order of magnitude to those recorded in human infants fed soy-based infant formula [117]. The genes that were significantly upregulated in gilts’ mammary gland were insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10), and fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF18). Additionally, in [116], soy-based infant formula was shown to increase mammary terminal end bud (TEB) numbers in a neonatal piglet model fed during the postnatal period. A few months later, the same team showed that the proliferative effect of soy formulas on mammary tissues in female piglets could be related to the inhibition of some miRNAs that in turn increased the expression of some genes involved in the cell proliferation process. More precisely, soy formulas reduced the expressions of miRNA-1, -128, -133a, -193b, -206, and -27a, which increased the mRNA expressions of the genes Ccnd1, Tgfb3, Igf1r, and Tbx3. These data were consistent with enhanced cell proliferation and the suppression of the apoptotic processes in the developing mammary gland and confirm those of Lamartiniere [65] in rats. Finally, data collected on pig models showed that dietary doses of genistein and/or soy Isofls exhibited a proliferative effect on neonatal piglets and on gilts’ mammary gland and reproductive tracts. However, these effects were only partially estrogenic when compared with those induced by oral E2.

3.3.2. Non-Human Primates

Monkeys were sometimes used as models to decipher the effects of soy or Isofls on reproductive tissues. As mentioned previously, monkeys are universal equol producers and, as such, the results from studies performed on monkeys cannot be translated to human beings. In addition, they seem to be poorly sensitive to Isofls, as indicated by two studies published in 2006 [118,119]. One was performed on ovariectomized female monkeys as models of menopausal women, while the other was performed on pre-menopausal female cynomolgus monkeys. In [118], high doses of Isofls (509 mg/day of genistein + daidzein) and racemic equol (1020 mg/day) were tested on the mammary gland and uterine tissues of ovariectomized cynomolgus macaques. Despite high plasma concentrations of Isofls (2.5 µM) and equol (6.9 µM), no significant effects were recorded on the observed organs. In [119], no effect was recorded on pre-menopausal female monkey with an Isofl daily intake equivalent to 120 mg/day for women. This confirms that the female monkey is much less sensitive than women since, as will be seen later, effects have been recorded in pre-menopausal women’s breast tissue with only 50 mg Isofls/day and on reproductive issues with 45 to 50 mg/day [10]. Nevertheless, the effects of such doses in menopausal women are not so well established.

In addition, a study was published in 1998 on the effect of a soy protein isolate (SPI) containing proteins and soy Isofls [120]. It reported results obtained only on five female macaques (Macaca fascicularis). The study compared the effects of E2, SPI alone, and SPI + E2. SPI alone was not estrogenic on the uterus or mammary glands. The amount of Isofls in the SPI was unknown, and thus, the validity of transposition of the study to humans remains in doubt. Nevertheless, although great variability was observed in the criteria studied, E2 + SPI tended to show a lower estrogenic effect than E2 alone. This was observed for mammary epithelial hyperplasia grade, mammary gland thickness, and cell proliferation in mammary gland tissues. However, for mammary gland area, the effect of E2 + SPI seemed to be additive.

To confirm the low sensitivity of monkey models to Isofls, the study by Woods et al. [121] did not show any effect of equol on the mammary gland of post-menopausal macaques. Equol was given at a dose equivalent to 120 mg/day for a human. Similarly, Schwen et al. [122] showed no effect of high dosages of equol on the uterine tract of cynomolgus monkeys.

3.4. Summary of Animal Experiments

All animal experiments analyzed here involved oral exposure and therefore induced BC cell contact with a cocktail of aglycone and conjugated molecules derived from soy and Isofls. These results suggest that Isofls delivered via an oral route can also be active in human beings. To summarize the animal approaches, toxicological experiments demonstrated that genistein was carcinotoxic for the mammary and pituitary glands of Sprague Dawley rats at doses that can be relevant for humans. In mice with chemically induced mammary tumors whose estrogen receptor statuses were not always characterized, Isofls inhibited the tumor growth when they were delivered at low doses in utero and before weaning. The effect of soy food seemed to be more conclusive than that of isolated Isofls. When soy or isolated Isofls were given after the cancerogenic substance, the results were less clear. The preventive effects of soy and/or Isofls on chemically induced tumors may be due to an early differentiating effect and an epigenetic effect or effect on the bioavailability and/or metabolism of the cancerogenic substances that counteracted the tumor proliferation. In mice implanted with MCF-7 cells (ER+, PR+, HER2−, and GPER+), Isofls enhanced the BC cell proliferation. The results were less clear with soy, and in several cases, the soy matrix prevented BC cell growth. In SCID mice, the results were different from those obtained on Balb/c mice. In mice implanted with TNBC cells potentially expressing GPER, physiological doses had no effects, while high doses tended to inhibit cell growth, as observed in vitro. The effect may be due to an interaction with GPER. At high doses, Isofls stimulated the cAMP pathway, inducing BC cell apoptosis. Finally, the results obtained in rodent models sustain the idea that Isofls may be protective of BC in the early stage of tumor development but enhance tumor growth when it is present. This is in accordance with the data published by Moller et al. [123]. In pigs, the effect of soy and Isofls at dietary levels was partially estrogenic or affected the mammary gland and the reproductive tract. This mimicked the effects recorded in humans with doses of 45 to 55 mg/day [10]. Finally, non-human primates did not seem to be adequate models for humans because of a poor sensitivity to Isofls.

4. Soy or Isoflavones and Breast Cancers in Clinical Trials

Soy and Isofls were tested on the mammary gland of women, and it sounds sensible to examine their actions on pre- and post-menopausal women separately. To understand why, we must recall what occurs at menopause and what could be the consequences at the breast tissue level. Indeed, menopause is ovarian function arrest. Ovaries are the main sources of cycling secretion of E2 and progesterone (P). During fertile life, these hormones are mainly secreted sequentially, but both of them are involved in breast tissue proliferation, differentiation, and maintenance. To summarize, estrogens induce the development of ductal tissue, P helps with ductal branching and lobulo-alveolar development, and during pregnancy and lactation, prolactin regulates milk protein production. When sexual life starts at puberty, E2 and P levels increase in the blood to initiate breast development [124]. Hence, the role of E2 is to induce cell proliferation in both the mammary glands and the uterus, while P, associated with its two PRs, seems to be involved in differentiation processes. These proliferative effects are mediated by ERs and can also concern cancerous breast and uterine cells as long as they express the ERs or GPER. As will be seen in the following paragraphs, the functional availability of ERs and PRs seems to be related to the availability of E2 and its metabolites [125,126], and E2 associated with its ERs induces the synthesis of PRs [127]. In the peri-menopausal stage, the ovarian hormones are still synthesized but in a chaotic way. Thus, the cycles tend to be irregular until they completely disappear. During that period, the ERs and PRs are still present, although the levels of PRs start to decline. Post-menopause, the levels of ERs rise in normal tissue, and it is hypothesized that this increases the tissue sensitivity to the remaining E2. During that period, a supplementation of xenoestrogen tends to attenuate the variations in estrogen plasma levels and to induce the synthesis of the PRs. The large variations in blood E2 occurring peri-menopause can induce hot flushes or night sweats, for instance. Later, when the peri-menopause phase ends, the ovarian hormones are no longer synthesized. Small quantities of E2 and P are essentially derived from adrenal gland synthesis. E2 is also obtained from the aromatization of androgens in the adipose tissue and from brain local synthesis. In this context of E2 deficiency, the functional availability of ER-β and PRs tends to decrease [126]. ERβ is known to have a greater affinity for Isofls than ERα and to counteract its proliferative action. According to [128], the decrease in E2 at menopause directly affects the immune response of women, reducing it, and this increases the risk of tumor development. However, other hypotheses can be drawn to explain the importance of timing in the effect of estrogen supplementation in menopausal women [129,130]. For instance, epigenetic modifications of ER promoters can silence the ERs in specific tissues and not in others [131]. Whatever the mechanism invoked, they explain why the reactions of pre-, peri-, and post-menopausal women to estrogens can be different and should be considered separately.

4.1. Clinical Effect of Isoflavones on Breast of Pre-Menopausal Women

Several studies have been conducted on the effect of Isofls on breast tissue of pre-menopausal women. In such cases, estradiol production is still present, and a synergy is potentially possible between Isofls and the endogenous E2.

Chronologically, the first study reporting the effects of soy Isofls on the breast of pre-menopausal women was that of Petrakis et al. [132], which evaluated the influence of the long-term ingestion of a commercial soy protein isolate on breast biology. This was assessed through the examination of nipple aspirate fluid (NAF). The study involved 24 non-Asian women who underwent nipple aspiration of breast fluid and gave blood and 24 h urine samples every month for 1 year. No soy was authorized in months 1–3 and 10–12. Between months 4 and 9 the women had to consume 38 g of the soy protein isolate containing 38 mg of genistein daily. The biological markers investigated were NAF volume, gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) concentration, and NAF cytology. Moreover, plasma concentrations of E2, progesterone, sex hormone binding globulin, prolactin, cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured. Compliance was assessed via genistein and daidzein measurements in urine samples. In pre-menopausal women, there was a 2–6-fold increase in NAF volume during soy exposure compared with the period without soy. No changes were recorded in the biochemical markers followed except for E2. This hormone was erratically elevated throughout a “composite” menstrual cycle which occurred during the months of soy consumption. Still, during this period, a moderate decrease in the mean concentration of GCDFP-15 was observed. Additionally, epithelial hyperplasia was cytologically detected in 7 of the 24 women (29.2%) when they were consuming the soy protein isolate. This pilot study indicated that chronic daily consumption of a soy protein isolate containing 38 mg genistein had an estrogenic effect on the pre-menopausal female breast. In the study, daidzein was not monitored, but because daidzein usually reaches a dose that is 1/3 of the total Isofls in soybean, it could be hypothesized that the Isofl exposure was about 57 mg/day in aglycone equivalent.

Two years later, Mc Michael-Phillips et al. [133] examined the effect of a soy supplement containing 45 mg of genistein and daidzein in aglycone equivalent on the dynamic of breast growth. The proliferation rate and the expression of PRs of histologically normal breast epithelium was examine in 48 pre-menopausal women. The subjects were diagnosed with benign or malignant breast disease and were randomly assigned to receive either their normal diet alone or their diet daily supplemented with a 60 g soy bar. The challenge lasted for 14 days. Samples of normal breasts were biopsied and labeled with [3H]-thymidine to detect the number of cells in the S phase. The proliferation antigen Ki67 was searched for via immunocytochemistry. Genistein, daidzein, equol, enterolactone, and enterodiol were measured in serum samples collected before and after the soy intake. The Isofl concentrations of genistein and daidzein increased in the soy group, as measured at day 14. A strong correlation between Ki67 and the thymidine labeling index (r = 0.868, p < 0.001) was recorded. The soy supplementation significantly increased the proliferation rate of breast lobular epithelium cells at day 14 d when an adjustment was performed on the day of menstrual cycle and the age of the patient. The expression of the PRs was increased significantly in the soy group.

A third trial was published by Hargreaves et al. [134] a year later. It recorded the effect of 14 days of dietary supplementation with 60 g of soy containing 45 mg of Isofls (genistein + daidzein) in aglycone equivalents on the normal breasts of 84 pre-menopausal patients. The plasma concentrations of genistein, daidzein, and equol were shown to increase after soy supplementation to reach 261 ± 266 ng/mL, i.e., ≈1 µM (p ≤ 0.025). Nipple aspirate (NA) levels of genistein and daidzein were higher than paired serum levels before (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively) and after soy intake (p < 0.001 and p = 0.049, respectively). NA levels of apolipoprotein D decreased significantly, and pS2 levels increased with soy supplementation (p ≤ 0.002). These markers denote an estrogenic stimulus. The authors did not observe any effect of soy on breast epithelial cell proliferation, ER and PR status, apoptosis, mitosis, or Bcl-2 expression. They concluded that short-term dietary soy had a weak estrogenic effect on the breast and that no anti-estrogenic effect of soy on the breast was detected at the doses tested.

In all trials, Isofls were tested in a soy protein isolate. The active dose seemed to be in the range of 45 to 50 mg/day of Isofls in aglycone equivalents. Such doses are known to induce an Isofl plasma concentration between 1 and 1.5 µM.

Conversely, high doses of Isofls in food supplements tend to decrease mammary density in pre-menopausal women, as shown by Lu et al. [135]. The authors recruited 98 controls and 99 treated participants who received 136.6 mg of soy Isofls in aglycone equivalents 5 days/week for up to 2 years. Changes in breast composition were measured at baseline and at yearly intervals via magnetic resonance imaging. Adherence to treatment was estimated based on regular blood measurements. Globally, mammary density, measured via the percentage of fibroglandular breast tissue (FGBT) at imaging, tended to decrease with soy Isofl intake. Hence, after an average of 1.2, 2.2, and 3.3 years of treatment, the FGBT% decreased by 1.37, 2.43, and 3.50%, respectively, when comparing Isofl exposure with the placebo. Daidzein appeared to be more efficient than genistein. The data were processed and adjusted for confounding factors before analysis. The effect seemed weak, and the ingested dose was high, corresponding to 5 to 6 soy portions/day.

Meanwhile, a study by Maskarinec et al. [136] showed no effect of Isofl supplementation at 10 mg/day on mammary density. Treated and control subjects were compared. In the study, which lasted 1 year and in which compliance was assessed via urinary Isofl and tablet counting, the authors were able to collect full data on 30 subjects only. Mammary density, which was assessed using follow-up mammograms, was not significantly modified by the treatment.

Another 2-year-long trial involved 201 pre-menopausal women (98 treated and 103 controls). The treated women were fed 50 mg of Isofls in aglycone equivalents daily through soy foods [137]. This trial did not reveal a significant effect of the treatment on mammary density. Lifetime soy intake was investigated using a questionnaire, and breast density was determined in screening mammograms at baseline and at the end of the trial. After 2 years, the mean percentage density had decreased by 2.8 and 4.1% in the treated and control women, respectively. Women who reported eating more soy showed higher densities than women who ate little soy. This difference was significant only in Caucasians. The authors also reported that lower soy intake in early life and higher soy intake in adulthood predicted a greater reduction in the percentage density during the study period.

A comprehensive review of 18 randomized control trials (RCTs) was published in 2021. The studies analyzed were conducted on healthy subjects on Isofls and considering BC risk factors [138]. In the studies retained, Isofls were administered through soy foods or supplements in amounts varying from 36.5 to 235 mg/day and for periods lasting from 1 to 36 months. Breast density was one of the biomarkers followed. However, in most of the studies, differences between the Isofl and control/placebo treatments were not detectable. Globally, compliance with Isofl treatment was found to be good, and a lack of a significant effect was seen irrespective of the kind of intervention, the dose of Isofl used, or the duration of Isofl treatment.

Finally, although breast density is an independent biomarker of BC risk, the clinical trials that involved pre-menopausal women generally concluded that Isofls had an estrogenic effect on breast tissue when Isofls from soy were ingested at plausible dietary levels, i.e., one or two industrial soy portions/day. In any case, dietary interventions showed an anti-estrogenic effect and a preventive effect on BC risk. In such studies, it remained very difficult to distinguish the effect of pure Isofls from that of soy, possibly because the doses of Isofls that were used were sufficient to counteract a potential preventive effect of other soy components.

4.2. Clinical Effects of Isoflavones on Breasts of Post-Menopausal Women

In 2015, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) gathered a working group to determine if Isofls could have deleterious effects on menopausal women. The scientific report produced [139] showed that the findings with respect to the mammary gland were non-threatening. Because Asian diets likely contain extra soy and Isofls, the panel only considered studies involving Western women. Considering the interventional trials included, which gathered 816 women, the expert panel concluded that there were no breast density or histopathological changes induced by soy Isofl/soy extracts, soy protein, daidzein-rich Isofls, genistein, or clover extracts. Based on the studies examined, the EFSA panel concluded that there were no observable adverse effects on the mammary gland in healthy post-menopausal women undergoing Isofl treatments. Table 6 summarizes the data from the studies retained by the EFSA panel.

Table 6.

Summary of the studies retained by the EFSA panel in 2015 [139].

Most of the studies performed on post-menopausal women did not consider the time since menopause. However, as the timing of estrogen treatment is considered crucial, no significant effect was expected to be seen in interventional trials dealing with the effect of Isofls on mammary tissue in post-menopausal women. Considering trials involving clover, it is important to note that the Isofls in this legume are methylated on the fourth carbon and require a hepatic transformation to be active [150]. Consequently, the bioavailability of genistein and daidzein in women’s plasma is lower than that in soy Isofls, and, again, an effect was not expected owing to the dosages applied. Moreover, the vast majority of the interventional studies involving women considered a current diagnosis or a history of BC as exclusion criteria. Therefore, the conclusion of the EFSA panel could not be applied to this subpopulation. Finally, considering the available data, the EFSA panel mentioned that it could not establish a clear statement for peri-menopausal women or for post-menopausal women with a current diagnosis or history of estrogen-dependent cancer. In addition, many studies on the effect of Isofls on physiological issues in post-menopausal women have been published. They did not notice an effect on breasts, but they were not designed for this purpose.

4.3. Clinical Effects of Isoflavones on Estrogen-Positive Breast Tumors

To the best of our knowledge, only one study on the effects of Isofls on female BC cells in vivo has been published so far, namely, the study by Shike et al. [151], which examined the effects of soy Isofl supplementation on breast-cancer-related genes and pathways. The study gathered 140 women recently diagnosed with early-stage BC. These women were randomly assigned to soy protein supplementation (n = 70) or placebo (n = 70) groups for 7 to 30 days depending on the time between diagnosis and surgery. Compliance with the treatment was determined via plasma genistein and daidzein measurements. Gene expression changes were evaluated using NanoString in tumors before and after ablation. Genome-wide expression analysis was performed on the post-treatment tissue. Biomarkers of proliferation (Ki67) and apoptosis (Cas3) were assessed via immunohistochemistry. Compliance was not optimal in the study, as evidenced by the levels of Isofls in the women’s plasma. Indeed, the lowest Isofl concentration was recorded in a volunteer from the treated group. Nevertheless, the study showed that globally, the levels of Isofls rose in the plasma of the soy group and did not change significantly in the placebo group, wherein the levels were not null. In an analysis pairing samples collected before and after food treatment, 21 genes (out of 202) exhibited altered expression. Some genes, such as FANCC and UGT2A1, were modified in terms of the magnitude and direction of their expression. A genomic signature obtained from a microarray analysis of tumors was associated with a high genistein intake and plasma concentrations. It consisted of 126 differentially expressed genes. This signature included an overexpression (>2-fold) of cell cycle transcripts, including genes promoting cell proliferation, i.e., FGFR2, E2F5, BUB1, CCNB2, MYBL2, CDK1, and CDC20. Because of non-optimal compliance and the short duration of treatment, Isofls did not induce statistically significant changes in Ki67 or Cas3 between the soy-treated and control groups. However, an increase in biomarker levels was observed when comparing pre- and post-treatment tumors in the soy-treated group. Finally, soy intake and high genistein levels in plasma were associated with the overexpression of FGFR2 and genes that drove cell cycle and proliferation pathways. These data contrasted with the effect of high doses (>10 µM) of in vitro Isofls on cell apoptosis [34,35], and they raised the concerns that soy Isofls could adversely affect gene expression in these tumors in women suffering from estrogen-dependent breast cancer.

5. Soy or Isoflavones and Breast Cancer in Population Studies

When performing population studies with estrogenic substances, there are many endocrine-related confounding factors to consider, and because Isofls are of nutritional origin, there are also many dietary factors that should be taken into consideration since they are known to be positively or negatively linked to soy intake and can modify the risk of BC. From an endocrine point of view, the risk of BC in women is affected by genetic traits that can be estimated by examining family histories of breast diseases and considering exposure to reproductive hormones, especially estrogens [152]. Therefore, an early full-term pregnancy has protective effects [153], while the risk increases with the number of menstrual cycles experienced during one’s lifetime. The risk is also increased by shorter cycles, a younger age at menarche, and a late onset of menopause [154]. A link between the number and duration of lactations and BC risk has not been demonstrated. Exposure to xenoestrogens is also a deleterious factor, as seen with medical treatments such as hormonal contraception or hormone replacement therapy or through exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors [155]. Exposure during the perinatal period has a particularly strong effect on BC risk [156]. Furthermore, when dietary issues are considered, it should be noted that some food components (such as fibers), fruits, vegetables [157] (including cruciferous vegetables [158]), green tea [159], and adherence to a Mediterranean diet [160] were shown to reduce the risk of cancer, including BC, even if the negative association is sometimes only suggestive. However, high-fat diets, meat [161], high-fat cheese [162], and alcohol-containing diets [163] have been associated with an increased risk of BC. Moreover, socioeconomic factors [164], BMI at the onset of menopause [165], lack of physical activity [166], alcohol, and tobacco have been shown to enhance the risk of BC. The age of the subject is generally associated with certain types of cancers and can be used as a criterion with which to decipher the effects of soy or estrogenic Isofls. Moreover, some studies have also sorted BC according to its clinical classifications, i.e., ER, PR, and HER2 status. These are characteristics of the tumors and should be considered separately. However, when subgroups are formed according to menopausal status or receptor status (the common practice), the number of cases in each subgroup lowers, reducing the power of the analysis and its significance. In all studies dealing with chronic diseases and nutritional factors, researchers adjust their data based on the age of the participants and energy intake. However, when the effects of soy and Isofls on BC are examined, the confounding factors for which adjustment of the data from population studies would ideally be required must be considered. These factors are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

List of the main confounding factors that should be considered for adjustment in population studies on the effects of soy and isoflavones on breast cancer risk.

The numbers listed in Table 7 are used in the following tables to evaluate the reliability of the population studies dealing with the effects of soy and/or Isofls on BC risk. On top of this list, all the studies analyzed adjusted their data on age and energy intake. As will be seen later, few population studies actually adjusted their observations according to all these confounding factors.

5.1. Limits of Population Studies

In Asian countries, specific food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) were developed to assess consumers’ soy and Isofl intakes [167]. They were used in population studies [168]. Some of these FFQs were validated either through reiteration—correlating responses between a first inquiry and other successive inquiries [169]—or comparison with urine or serum Isofl levels [170]. Usually, the correlation between two retrospective FFQs is around 50% at best; this can be explained by the time between the inquiry and the period of life investigated [171]. Similar correlation levels were recorded with Isofl measurements in biological fluids [167], and they seem rather low. Hence, when Asian soy foods were recorded in these studies, it can be assumed that the Asian soy intake was reasonably well determined. However, when Isofl were considered, the low correlation between putative intake and biological measurements in human tissues may indicate that the estimation is not optimal. Because exposure to soy and Isofls is considered constant in Asian countries, a steady-state level of Isofls would be expected in biological samples. Because exposure to soy and Isofls is considered constant in Asian countries, a steady-state level of Isofls would be expected in biological samples. However, this is not the case, and the poor correlations between soy intake and blood levels of Isofls could be explained if a significant proportion of the soy consumed was still prepared at home and in a traditional fashion. In doing so, Asian people would be applying water treatments, which would reduce the Isofl levels in their foods. Unfortunately, this is not the case when soy is prepared at industrial scales, wherein using tons of water can be tricky [16]. Therefore, at least three biases can undermine the Asian studies on soy and Isofl consumption. The first one is an overestimation of the Isofl intake if it is estimated from measurements taken cotemporally from industrially prepared soy foods. The second one is memory failure, preventing the estimation of soy intake a long time before an inquiry. The third bias is the evolution of the preparation processes over time. The quality of and, most probably, the Isofl concentrations in soy foods traditionally prepared at home have been modified. This bias should not be underestimated when researchers are trying to determine the effect of soy intake among adolescents on the risk of BC at the onset of menopause.

Conversely, in Western countries, where soy products are largely industrially produced, the estimation of Isofl intake is not compromised by this bias. However, aside from the soy foods identified earlier and declared in the FFQ assessing soy intake, there is also hidden soy incorporated in many transformed foodstuffs. While soy foods are generally consumed occasionally in Western countries, the contribution of Isofls from hidden soy to phytoestrogen exposure is proportionally high. Failing to account for this source of soy can induce a major bias in Isofl exposure estimation, compromising the correlation between soy records and Isofls in biological fluids [172] and potentially affecting the accuracy of the stratification of a cohort into subgroups. Additionally, earlier in this review, we mentioned that Isofls can have an effect on breast development in pre-menopausal women when the intake of Isofls (aglycone equivalents) reaches 45 to 50 mg/day [132,133,134]. However, in Western countries, such a dose is usually reached only occasionally or with food supplements. Thus, when the population is stratified, only a few subjects from the upper quartile can potentially be affected by their Isofl intake, and they may be hidden by the majority of the group. Finally, the estimation of Isofl intake seems to be deeply biased in both Western and Asian studies for various reasons.

As explained previously, investigating the effects of soy on human health requires accounting for genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors (endocrine disruptors and diet patterns) because Isofls have endocrine effects. As mentioned previously, the female populations studied are usually very heterogenous even if classified in the same category. Indeed, the hormonal response varies greatly in women while menopause progresses. Therefore, according to Monier et al. [173], a relationship between soy or Isofls and health issues should only be considered relevant if the p-value is <0.005. Indeed, if the estimation of intake is biased, many confounding factors are missed, or the population observed is very heterogenous, all results from the corresponding meta-analysis would have to be considered cautiously.

5.2. Case–Control Studies Involving Soy and Isoflavones

The oldest case–control studies on this issue essentially dealt with soy intake. In the previous century, Isofl assays were not frequently performed, and it is plausible that industrial soy foods were not as widespread as they are now. Thus, if it is assumed that homemade soy foods created following traditional recipes contained less Isofls than industrial ones [16], a pure soy effect would have been more likely to have been seen 30 years ago. When Isofls were included in these analyses, it was essentially through an estimation calculated via measurements gathered from databases. These measurements were made using commercial products and may not completely reflect the composition of traditional homemade soy foods. Furthermore, it appears crucial to use databases adapted to the potential food items eaten by the subjects. Thus, a Japanese database should be used in Japan, just as a Chinese database should be used in China. Additionally, measurements made a long time before or after exposure may be irrelevant. This could be the case when assessing Isofl exposure during adolescence with respect to post-menopausal women. Indeed, because the industrialization of food production has progressed globally, it might be erroneous to assume that the tofu eaten 40 years ago is the same as that eaten nowadays.

Table 8 shows that the effects of soy and/or Isofls were not always consistent.

Table 8.

Summary of case–control studies on soy and/or isoflavones and breast cancer risk.

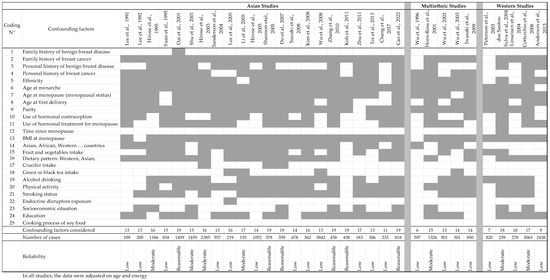

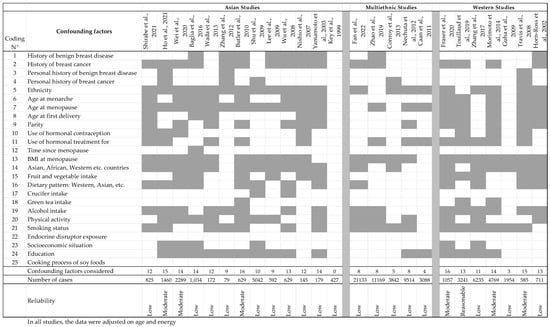

Table 8, all studies considered the women’s age and energy intake to be potential confounders. Nevertheless, several confounders were hardly or never taken into consideration, as seen in Figure 2, including family history of benign breast diseases, time since menopause, exposure to endocrine disruptors, and origin of the soy foods eaten (commercial or homemade). In addition, crucifers and tea consumption were only recorded a few (two or three) times.

Figure 2.

List of relevant confounding factors that should be taken into consideration when analyzing results from case–control studies on soy and/or isoflavones, and breast cancer risk, and the factors analyzed in the different studies. The studies mentioned in the tables are [21,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,204]. Finally, a reliability score was assigned by combining the number of cases included in the studies and the missing confounding factors.

In Table 8, the studies are sorted based on studied population, Asian, multiethnic, or Western populations, because exposure to soy and Isofls appeared to be quite different in terms of quality and quantity. Finally, most of the studies were of low quality, often having a low number of subjects and numerous missing confounders (Figure 2). Looking closer at the results, the most recent studies seem to be the most reliable, taking into account more confounding factors and gathering more subjects. Unfortunately, during data interpretation, the authors often split their population according to menopausal or receptor status, which significantly decreased the reliability of their conclusions while decreasing the number of subjects. On some occasions, especially in Asian studies, no p-value was given.

Hence, in the earliest studies performed in Singapore [174,175], soy consumption was rather low, with soy food intake being assessed at a maximum of 55 g/d. In these studies, the amount of soy protein consumed was estimated at less than 4 g/d. However, in studies published a few years later, the soy food intake in China was 5 or 6 times higher [177,178,181], as was the soy protein intake. While the first few studies showed a preventive effect of soy on BC risk, this was no longer the case afterward, in studies with higher amounts of soy intake. In this context, the study by Zhu et al. [191] showed low reliability, reporting soy consumption at the same order of magnitude as that in previous Chinese studies. The number of subjects was low, and several confounding factors were not considered (parity, breast feeding, hormonal treatments for contraception or menopause, endocrine disruptors, etc.). Moreover, the study showed a protective effect of soy on ER+PR+ BC but no effect on other types of BC, indicating that soy and Isofls estimated in the range of <7.56–>28.83 mg/d could act as anti-estrogens. In 2022, Cao et al. [194] showed a protective effect of soy associated with fruits and vegetables on ER−/PR− BC but not on ER+/PR+ BC. While this result is in conflict with previous studies, it showed that the effect of soy can be affected by the concomitant consumption of healthy foods. Therefore, it should be noted that the more recent the studies, the better reliability due to the more comprehensive assessments of confounding factors.

The deleterious effect of high soy consumption was confirmed in the study by Lee [182] conducted in Taiwan, where the soy food intake was 10 times higher than that recorded previously in Singapore. In the study, soy consumption was associated with an increased risk of BC, although this association was not significant and many confounding factors were not considered. Later, Chang et al. [193] reported that soy associated with a vegetarian diet was protective against BC. In that study, the highest consumers consumed soy foods more than once a day. However, many confounding factors were not considered in that study, and its reliability remained low.

Looking at data obtained in Japan, the same tendency to increase soy consumption was observed. In 1995, Hirose et al. [176] fixed their highest tertile at a consumption of three soy foods/week, while in 2003, the highest quartile was >five times/week [180]. In 2005, the study by Hirose reported a highest soy consumption at around 56 g/d [18]. In that study, based on dietary recalls from the previous year, tofu was considered protective against BC, while fried tofu was not, indicating that the protective effect of soy and/or Isofls was limited and counteracted by fat intake. This finding also means that the effects of soy or Isofls, if any, can be easily masked by those of other food components.

Two studies were retained here that were performed in Korea. It is difficult to address the total amount of soy and Isofl consumed from these studies since they looked at peculiar soy-foods items only, without indication on other soy-food items. Nevertheless, the first study [185] showed that soybeans and soy paste have potentially protective effects, while soy milk, soy curd, and total soy do not. This would suggest that Isofls are not protective substances since they are present in all soy foods. The study by Kim et al. [187] showed a protective effect pre- but not post-menopause. However, some confounding factors such as family history of BC were not addressed, and the numbers of cases and controls were low, especially after stratification based on menopausal status.

Multiethnic approaches allow for a comparison of a vast range of soy and Isofl consumption amounts, optimizing the chance to observe an effect. These studies were mainly performed in the USA [195,196,197,198], except one involving Japanese and Brazilian subjects [199]. Soy appeared to have a protective effect against BC in four out of five studies. The only study that did not show a preventive effect was [196], which reported low levels of soy and Isofl intake. Isofl exposure was estimated based on tofu and miso consumptions. The frequencies were classified as zero or ≥once per week, and the highest median of Isofl intake was 2.775 mg/day. The reliability of the study was considered to be moderate based on the number of participants and the confounding factors considered. At this dose, phytoestrogens are not likely to exhibit any effect.

Regarding the other studies, a progressive increase in soy consumption was again noticed. In the study by Wu et al. [195], the highest tofu intake was over 55 times/year and the lowest was below 12 times/year. Later, in 2002, the same team recorded a highest intake at more than four times per week and a lowest below once a month [197]. In that study and the following one [198], Isofl intake was estimated, with the highest median intake at 12.88 mg /1000 kcal and a range of 20 to 25 mg of Isofls/day. This dose has not been shown to exhibit any effect on women’s breast. However, soy intake can be associated with a more vegetarian dietary profile as well as higher green tea consumption, which have been shown to have preventive effects on breast cancer. Based on the number of subjects involved and the confounders missed in the analyses, these studies were considered to be of low reliability. Finally, the study by Iwasaki et al. [199] should be analyzed. Their estimations of soy and Isofl intake were based on dietary recall from a previous year and on the Isofl concentrations recorded for commercial soy foods. The study only analyzed miso and tofu consumption in paired cases and controls, with 390 Japanese, 81 Japanese Brazilian, and 379 non-Japanese Brazilian participants. The highest median intake of Isofls was 71.3 mg/day, which may be proliferative on breast cells. This study showed that the higher the soy and Isofl intake, the lower the risk of BC. However, the lowest Isofl intake was observed on Brazilian women whose BMI was significantly higher, meat intake was higher, and vegetable consumption was lower. The analysis did not adjust the data for these parameters, conferring low reliability to the study. Finally, the highest Isofl intake was recorded in Japanese women based on a database established on commercial soy foods. In Japan, a significant proportion of menopausal women prepare their soy foods at home with lower Isofl concentrations, but this fact was not assessed.

In the studies performed on Western populations and listed in this review [200,201,202,203,204,205], the exposure of the populations to soy and Isofls was low, and in all those studies, the majority of the population was estimated to be exposed to less than 1 mg/day of Isofls. Only the study by Cotterchio et al. [204] reported a maximum intake of 158 mg Isofls in the fifth quintile of population. In all these studies, soy or Isofl consumption was not associated with BC risk except in the study by Anderson et al. [205], which showed an increase in the risk of ER−PR− BC with low doses of Isofls. However, the reliability of that study remains low, especially because stratification of the population based on estrogen receptor status resulted in a low number of subjects in each subgroup.

Scientists have tried to determine the effect of soy and Isofls based on menopausal status; however, the effect remains unclear. In Asian populations, four studies showed a protective effect pre-menopause [176,180,187,189], while one showed a protective effect post-menopause [191]. Only the studies in [176,189] had moderate and reasonable reliability, and both advocate for a preventive effect pre-menopause.