A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

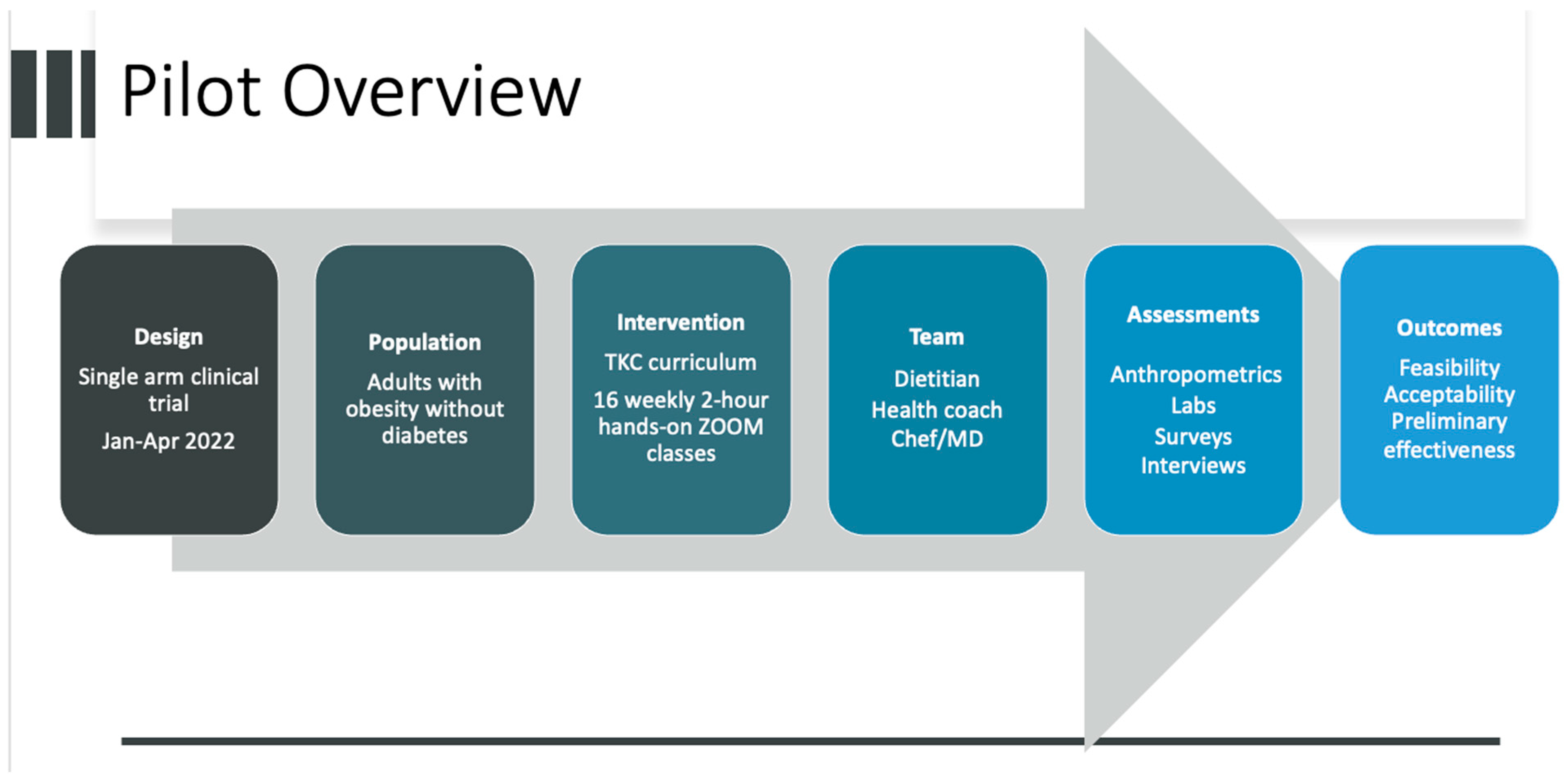

2.1. Study Design and Recruitment (Figure 1)

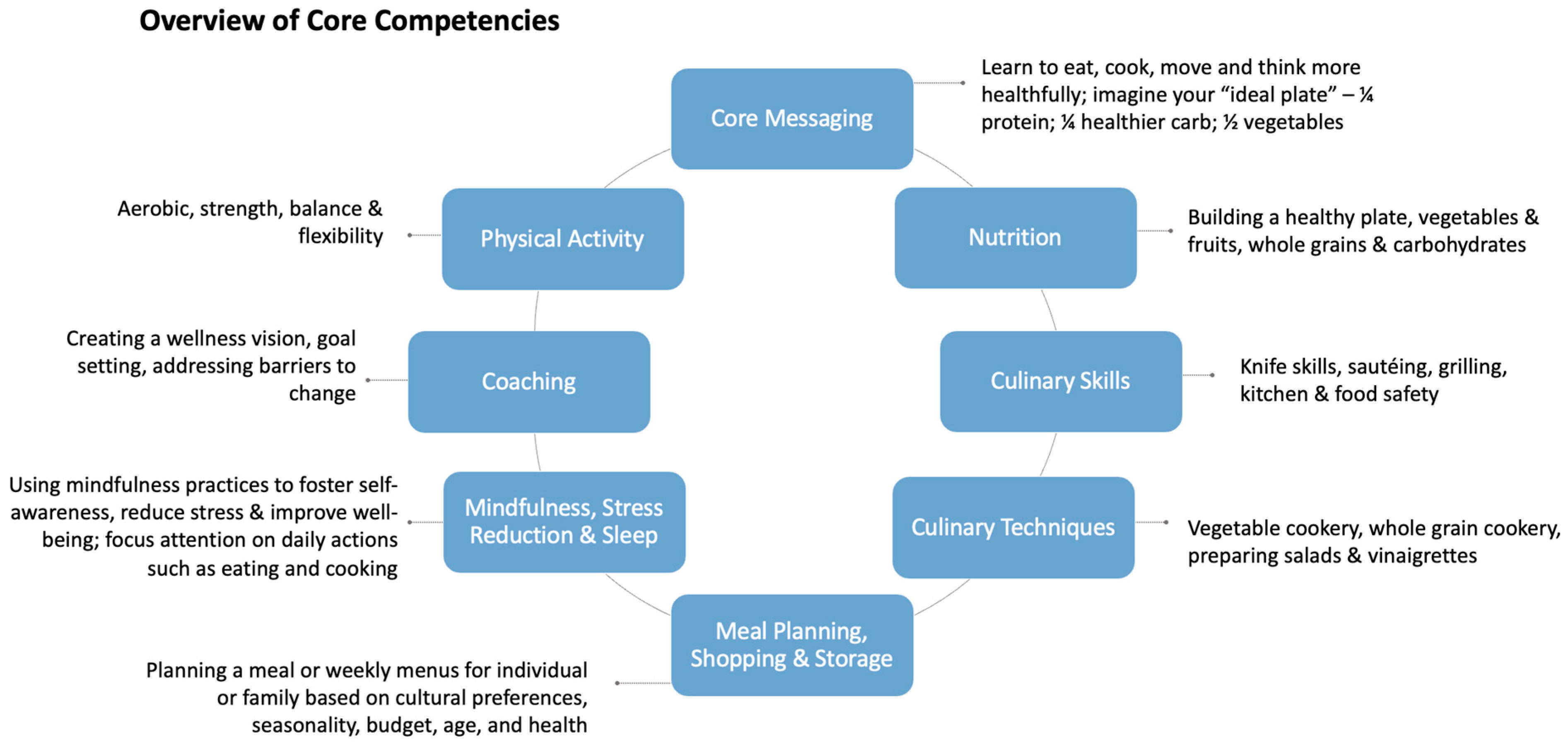

2.2. Development of the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC)

2.3. Program Description/Study Intervention

2.4. Teaching Kitchen Facilities

2.5. Assessment and Measures

- Meal planning and food shopping were captured through 5 items asking about meals prepared at home and use of nutrition labels [64].

- Dietary patterns were captured using 4 items from the Prime Diet Quality Score 30 (PDQS-30) [69] for intake of whole grains, refined grains/baked goods, salty snacks, and sugary drinks (PDQS-30 questions 20, 21, 22, 23). Two items combined several questions from the PDQS-30 to measure overall fruit and vegetable intake:

- ○

- Fruit: Over the past month, how often did you eat fruits (include only whole fruit, not juices)?

- ○

- Vegetable: Over the past month, how often did you eat vegetables (including fresh, frozen, or canned, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish)?

- Mindful eating was assessed using 3 items from the Mindful Eating Questionnaire [70]. These focused on satiety awareness, mindless snacking, and sensory food appreciation, topics highlighted in the curriculum.

- Movement was assessed with the Exercise Vital Sign [71].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Feasibility

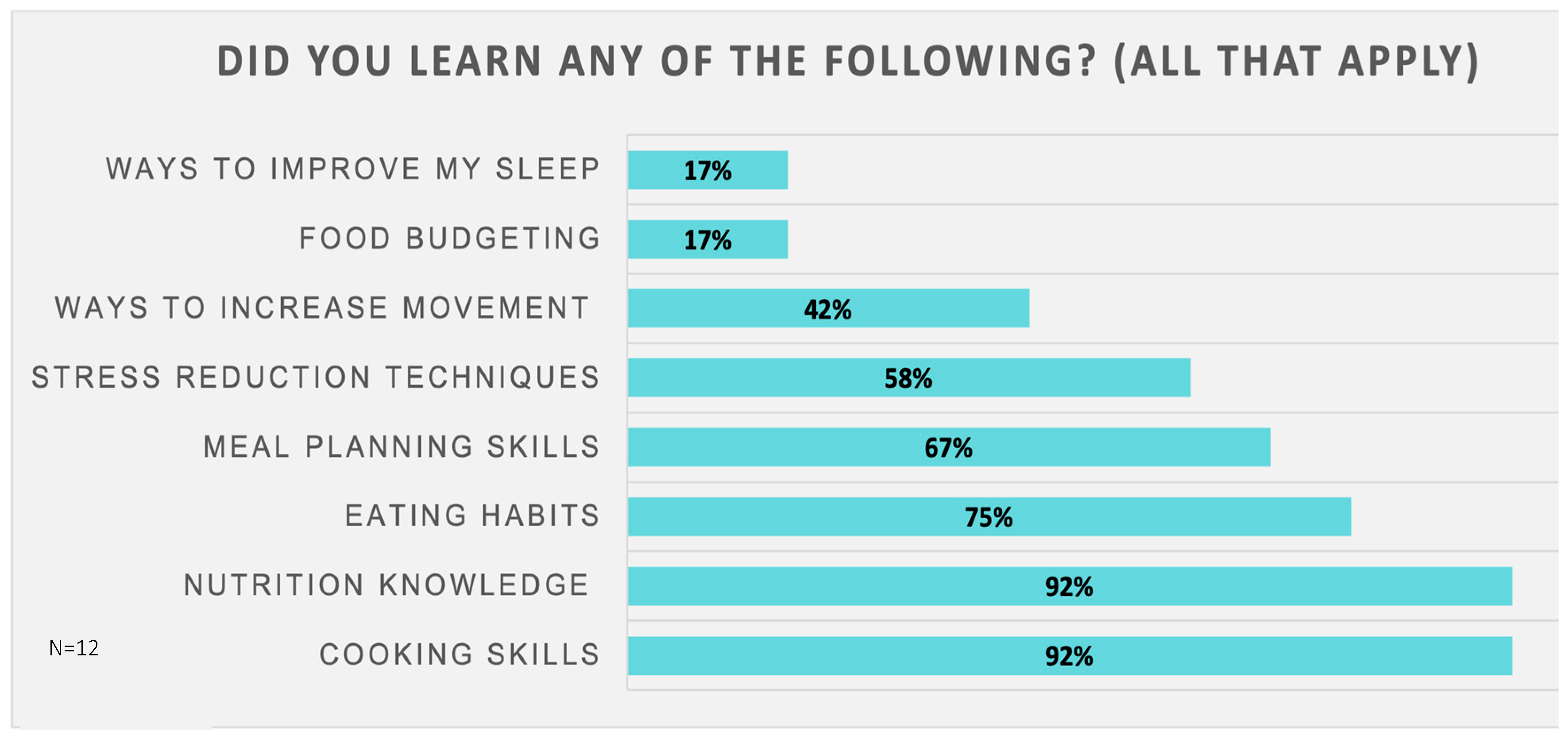

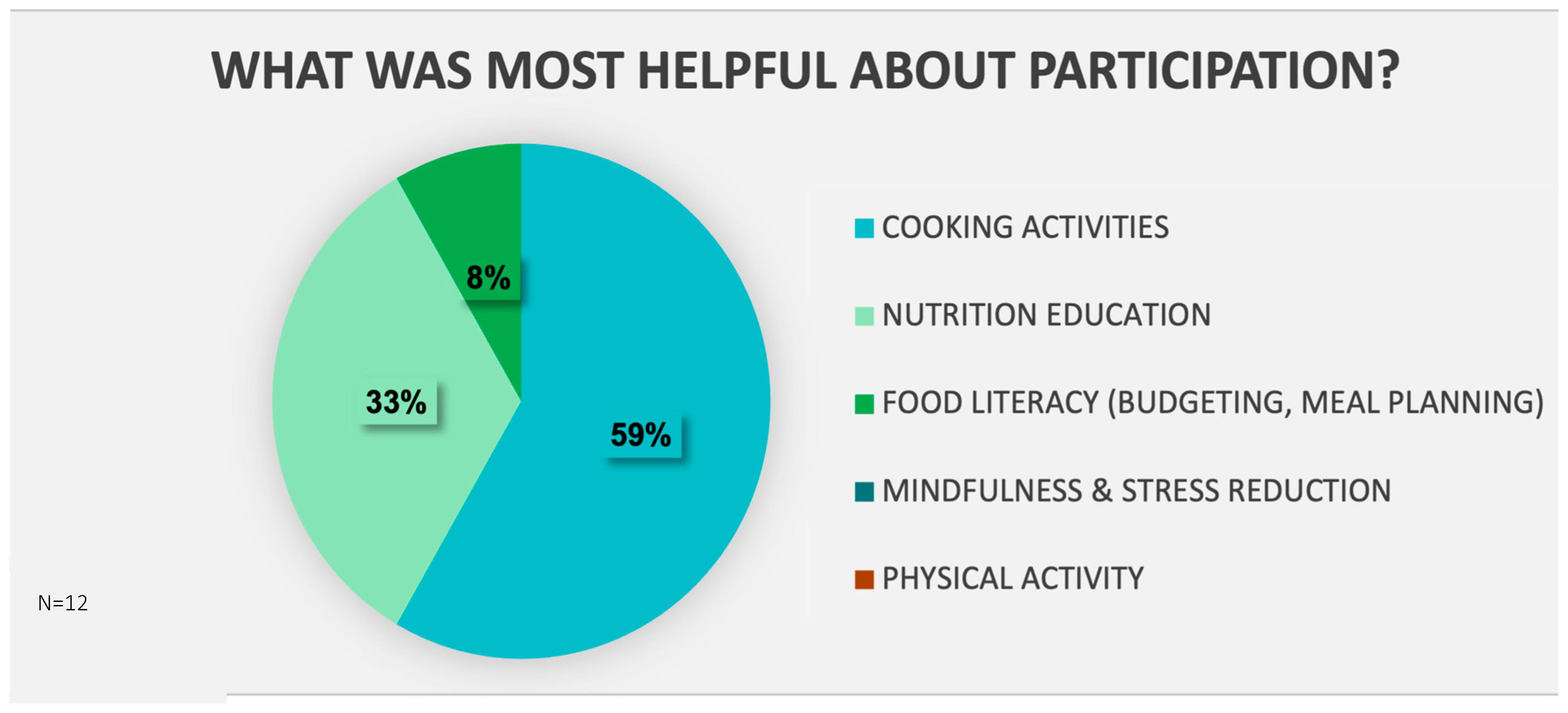

3.3. Acceptability

3.4. Effectiveness

3.4.1. Teaching Kitchen Survey (Table 2)

| Survey Question | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Class Mean (SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and wellbeing | |||

| In general, would you say your health is? [Likert 0–5, poor, fair, good, very good, excellent] [62] | 3.0 (0.74) | 2.9 (0.67) | 0.59 |

| How would you rate your current “work-life” balance? With 1 being poor and 10 being very good [50]? | 5.8 (2.66) | 6.0 (2.66) | 0.83 |

| How would you rate your current sense of well-being? With 1 being poor and 10 being very good [63] | 6.1 (2.12) | 7.7 (2.27) | 0.02 |

| Meal planning and food shopping | |||

| The last time you went grocery shopping, did you use the nutrition facts label to guide your choices? [Likert 0–3, never/rarely, sometimes, often, usually/always] [75] | 1.0 (1.13) | 1.75 (1.14) | 0.02 |

| How many days a week do you prepare your main meal/dinner from “scratch” using fresh ingredients (including fresh, frozen, or canned produce)-ok to count your own leftovers? | 3.83 (2.33) | 5.92 (1.68) | <0.01 |

| How confident do you feel about being able to prepare your main meal/dinner from “scratch” using fresh whole ingredients (including fresh, frozen, or canned produce)? [Likert 0–4, not at all confident, not very confident, neutral, confident, extremely confident] | 3.33 (0.89) | 3.67 (0.49) | 0.10 |

| The next few questions will ask you about cooking at home. By cooking at home, I mean a meal prepared at home from scratch using vegetables, meats, grains, or other fixings [50]. | |||

| Thinking about the past 7 days, on how many days did you, personally, cook lunch at your home? | 2.83 (1.95) | 3.92 (2.78) | 0.22 |

| Thinking about the past 7 days, on how many days did you, personally, cook dinner at your home? | 3.08 (1.62) | 5.33 (1.44) | <0.01 |

| Culinary skills and techniques—adapted from the Culinary Attitude and Self-Efficacy Scale, Cooking Assessment Questionaire. [67,68] | |||

| Indicate the extent to which you feel confident about performing each of the following activities [Likert 0–4, not at all confident, not very confident, neutral, confident, extremely confident] | |||

| Using knife skills in the kitchen | 3.33 (0.65) | 3.67 (0.49) | 0.10 |

| Using basic cooking techniques | 3.33 (0.65) | 3.58 (0.67) | 0.19 |

| Steaming | 3.00 (0.60) | 3.67 (0.65) | 0.03 |

| Sautéing | 2.92 (1.24) | 3.75 (0.45) | 0.03 |

| Stir-frying | 2.83 (1.03) | 3.83 (0.39) | <0.01 |

| Grilling | 2.42 (1.24) | 3.25 (0.97) | 0.02 |

| Poaching | 1.25 (0.87) | 2.5 (1.09) | <0.01 |

| Baking | 3.08 (0.90) | 3.5 (0.67) | 0.02 |

| Roasting | 2.92 (1.0) | 3.67 (0.65) | 0.02 |

| Stewing | 2.08 (1.56) | 3.25 (1.06) | 0.01 |

| Simmering | 2.83 (1.12) | 3.67 (0.65) | 0.03 |

| Preparing fresh or frozen green vegetables (e.g., broccoli, spinach) | 3.33 (1.16) | 3.75 (0.62) | 0.30 |

| Preparing root vegetables (e.g., potatoes, beets, sweet potatoes) | 3.00 (1.04) | 3.75 (0.45) | 0.02 |

| Preparing fruit (e.g., peaches, watermelon) | 3.58 (0.67) | 3.83 (0.39) | 0.28 |

| Using herbs and spices (e.g., basil, thyme, cayenne pepper) | 2.75 (1.29) | 3.5 (0.67) | 0.08 |

| Planning nutritious meals [in advance] | 2.17 (1.34) | 3.08 (0.90) | 0.03 |

| Following a recipe (ex., salsa from tomatoes, onion, garlic, peppers) | 3.25 (0.62) | 3.67 (0.49) | 0.05 |

| Preparing a meal from items on hand (ex., in pantry and refrigerator) | 2.75 (1.14) | 3.42 (0.67) | 0.04 |

| Adapting a recipe to use fresh whole ingredients that are on hand | 2.42 (1.24) | 3.25 (0.75) | 0.03 |

| Mindful eating | |||

| How often do you eat mindfully, with thoughtfulness and intention? [Likert 0–3, never/rarely, sometimes, often, usually/always] | 1.00 (0.74) | 1.42 (1.08) | 0.14 |

| Mindful Eating Questionaire—3 items: [70] | |||

| I snack without noticing that I am eating. [Likert 1–4, never/rarely, sometimes, often, usually/always] | 2.58 (0.79) | 1.83 (0.72) | 0.02 |

| I stop eating when I am full even when eating something that I love. [Likert 1–4, never/rarely, sometimes, often, usually/always] | 2.0 (0.95) | 2.58 (1.08) | 0.05 |

| Before I eat, I take a moment to appreciate the colors and smells of my food. [Likert 1–4, never/rarely, sometimes, often, usually/always] | 1.5 (0.80) | 2.5 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Food security and access | |||

| How far is the closest grocery store from where you live? | 83% <10 miles | 83% <10 miles | |

| Hunger Vital Signs: [65,66] | |||

| Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more. [Likert 0–4, often true, sometimes true, never true, do not know/not sure] | 92% never true | 100% never true | 0.34 |

| Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just did not last, and we did not have money to get more. [Likert 0–4, often true, sometimes true, never true, do not know/not sure] | 100% never true | 92% never true | 0.34 |

| Movement—Exercise Vital Signs [71] | |||

| On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity? (like a brisk walk)? | 2.67 (2.2) | 3.58 (2.4) | 0.10 |

| On average, how many minutes per day do you engage in physical activity at this level? | 21.7 (17.5) | 26.7 (17.8) | 0.24 |

| Sleep | |||

| How many hours do you usually sleep in a 24 h period (including naps)? [Likert 1–5: Less than 5 h, 5–6 h, 6–7 h, 7–8 h, 8+ h] [73] | 3.58 (0.79) | 3.33 (0.65) | 0.19 |

| During the past month, how would you rate how your sleep quality overall? [Likert 1–4: very good, fairly good, fairly bad, very bad] [72] | 2.08 (0.67) | 1.92 (0.52) | 0.34 |

3.4.2. Additional Survey Instruments (See Appendix C)

3.4.3. Anthropometrics and Biometrics (Table 3)

| Measure | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Class Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.6 (2.5) | 35.4 (2.6) | 0.53 |

| Weight (kg) | 96.1 (10.2) | 95.6 (9.6) | 0.50 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 111.8 (8.2) | 111.4 (8.0) | 0.57 |

| Fasting Glucose | 102.5 (12.7) | 101.3 (12.4) | 0.64 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 5.4 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.4) | 0.20 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 200.2 (46.2) | 194.6 (42.5) | 0.16 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 159.3 (90.3) | 157.7 (106.3) | 0.90 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 120.5 (31.9) | 113.3 (26.2) | 0.03 |

| HDL | 47.8 (6.6) | 49.9 (7.8) | 0.13 |

| ALT | 25.3 (16.7) | 24.5 (13.7) | 0.71 |

| Insulin | 17.8 (14.0) | 16.5 (7.0) | 0.66 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Curriculum Domains and Core Competencies

| Nutrition |

| Evidence based nutrition recommendations |

| Healthy Plate, link between diet and health |

| Vegetables and fruits |

| Whole grains and carbohydrates |

| Healthy fats and oils |

| Proteins: beans and legumes, animal sources, seafood |

| Dairy and drinks |

| Fermented foods |

| Breakfast, lunch, dinner, dessert |

| Eating out and special occasions |

| Recipe adaptation |

| Culinary Skills |

| Knife skills, kitchen safety |

| Sautéing, stir-frying, searing |

| Grilling |

| Broiling |

| Roasting, baking |

| Steaming |

| Poaching |

| Boiling, simmering |

| Stewing, braising |

| Pressure/slow cooking |

| Emulsifying, whisking |

| Grating, zesting |

| Culinary techniques |

| Vegetable cookery |

| Whole grain and pasta cookery |

| Salads and vinaigrettes |

| Bean and legume cookery |

| Soups, stock, stews and curries |

| Yogurt-based sauces |

| Egg cookery |

| Meat cookery |

| Basic baking and whole food desserts |

| Adding flavor, herbs and spices |

| Meal Planning and Food Shopping |

| Meal planning and preparation |

| Navigating food retail locations (grocery stores, farmers’ markets, CSAs, etc.) |

| Reading food labels/using nutritional info |

| Strategies for saving money while food shopping |

| Limiting food waste through planning, shopping, storage |

| Stocking a pantry, food staples |

| Food storage and food safety |

| Mindfulness, Mindful Eating, Stress |

| Benefits of using mindful practices to foster self-awareness |

| Recognizing how mindful practices focus attention on action (such as eating and cooking) |

| Using mindful practices to reduce stress and improve well-being |

| Types of mindful practices (meditation, awareness, breathing, mindful eating) |

| Strategies for incorporating short mindful practices into one’s daily routine |

| Self-compassion |

| Happiness and joy |

| Behavior Change Strategies |

| Creating a wellness vision |

| Goal setting |

| Working with emotions |

| Problem solving |

| Planning for success, sustaining change |

| Small changes add up, persistence |

| Physical Activity |

| Balance and stretching |

| Strength |

| Aerobic activity |

| Link to health |

| Sleep |

| Basic sleep recommendations and link to health |

Appendix B. Curriculum Outline

| Week | Class Topic/Theme (Nutrition-Based) | Recipes (Serve 4) V = Vegetarian Option | Culinary Techniques | Culinary Skills Knife Skills in All | Goal Setting, Mindfulness & Exercise |

| 1 | Building a healthy plate Nutrition overview Obesity as a disease Pillars of lifestyle change | Roasted veggies pasta Roasted veggies (separate recipe) | Pasta cookery Roasted veggies Flavor profiles, cuisines & cultures | Knife skills intro Boiling pasta Roasting veggies | Goal setting Introduction to SMART goals Wellness vision/why |

| 2 | Vegetables & fruits Sustainability, planetary impact | Farmer salad with seared Salmon V = Pan-roasted chick peas | Egg cookery Making vinaigrette Fish cookery Making salads | Emulsifying/whisking Blanching Searing/sautéing fish Boiling eggs | Mindfulness: introduction Mindful bite |

| 3 | Whole grains & carbs Glycemic index, carbohydrate quality | Farro salad Quick farro sauté | Grain cookery Making vinaigrette Making salads | Chopping nuts Toasting nuts Sautéing veggies Emulsifying/whisking | Exercise: introduction Flexibility fitness break |

| 4 | Healthy fats & oils | Tofu & veggie stir fry | Making a stir-fry | Stir-frying | Mindfulness: mindful meditation |

| 5 | Protein—beans & legumes fiber | Turkey veggie chili V = canned beans | Making chili/stew Yogurt sauces | Toasting spices Sautéing veggies | Exercise: aerobic fitness break |

| 6 | Protein—animal Planet health | Roasted chicken with root veggies—sheet pan dinner V = canned chick peas | Sheet pan meals | Roasting meat/veggies | Mindfulness: 3 min breathing |

| 7 | Protein—seafood | Fish taco with rainbow slaw V = canned black beans | Making tacos Making slaw Fish cookery Yogurt sauces Making vinaigrette | Searing/sautéing fish Emulsifying/whisking | Exercise: strengthening fitness break ideas |

| 8 | Dairy, drinks & fermented foods Sugars, fructose and artificial sweeteners | Infused waters and teas Yogurt parfait Grilled marinated tofu + asparagus Yogurt ranch dressing | Infusing water Cooking with tofu Yogurt sauces | Grilling | Midway goals |

| 9 | Shopping & label reading Spices & hearty greens | Chana masala Garlicky greens Lentils | Making curry/stew Using spices | Sautéing veggies | Exercise: balance fitness break |

| 10 | Breakfast Sleep & meal timing | Frittata (egg cups) Overnight oats V = Tofu scramble | Egg cookery (baked) hot cereals | Baking eggs | Mindfulness: body awareness exercise |

| 11 | Lunch & snacks Managing stress | Kale salad Tuna nicoise sandwich V = Chopped veggie + egg sandwich | Vinaigrette Hearty greens Toasting nuts Grain cookery Egg cookery Making salads | Boiling Emulsifying/whisking Baking/toasting Grating/Microplane | Exercise: flexibility fitness break |

| 12 | Dinner & shopping/meal planning | Roasted cauliflower & sweet potato Black bean turkey burgers V = Black bean, carrot & sweet potato burger | Roasted veggies Blended burgers Yogurt sauces | Roasting veggies Searing/grilling meats Chopping herbs/garlic | Mindfulness: 3 min breathing exercise |

| 13 | Eating out & special occasions | Red lentil pasta with marinara | Pasta cookery Making a sauce | Boiling | Exercise: aerobic fitness break |

| 14 | Desserts & added sugar | Walter Willett concept—chocolate, nut & fruit plate Baked apple Moroccan carrot lentil soup | Baked/grilled fruit Making soups Legume cookery | Baking fruit | Mindfulness: strengthening fitness break |

| 15 | Recipe modification Nutrition review | Cauliflower quinoa mac & cheese | Making casseroles Grain cookery | Baking Roasting veggies | Exercise: walking meditation exercise |

| 16 | Putting it all together: Lifestyle patterns | Grain bowl with choice of grain + protein + vegetable + sauce cook off! | Egg cookery Grain cookery Yogurt sauces | Blanching Searing/grilling meat/tofu | Final goals Reflect back to why/wellness vision & SMART goals |

Appendix C. Additional Survey Assessments

| Scores | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Class Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness Sub Score | 2.12 (0.68) | 2.62 (0.71) | 0.01 |

| Distraction Sub Score | 2.75 (0.25) | 2.74 (0.58) | 0.94 |

| Disinhibition Sub Score | 2.43 (0.63) | 2.97 (0.71) | 0.01 |

| Emotional Sub Score | 2.29 (0.74) | 2.80 (0.73) | 0.01 |

| External Sub Score | 2.34 (0.44) | 2.56 (0.61) | 0.20 |

| Total Score | 11.94 (1.89) | 13.68 (2.64) | 0.01 |

| Survey Question | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post Class Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over the past month, how often did you eat/drink … [≤once/month, 2–3 time/month, 1–2 times/week, 3–4 times/week, 5–6 times/week, once a day, ≥2 times/days] | |||

| Q1. dark green leafy vegetables? Include fresh and cooked vegetables, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods: Spinach, kale, Swiss chard, arugula, collard greens, mustard greens, romaine lettuce, Bok choy | 2.92 (0.79) | 3.83 (1.19) | 0.06 |

| Q2. cruciferous vegetables? Include fresh and cooked vegetables, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods: Cabbage (white, red, Chinese), broccoli, Brussel sprouts, cauliflower, turnip, radish, rutabaga, kohlrabi | 2.92 (1.0) | 3.83 (0.83) | 0.01 |

| Q3. deep orange vegetables? Include fresh, frozen, canned, or thermally processed vegetables, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods: Carrot, pumpkin, sweet potato, dark orange squash such as butternut. | 2.75 (1.14) | 3.58 (1.0) | 0.06 |

| Q4. potatoes (mashed or baked)? Include when eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Do NOT include sweet potatoes, French fries or chips. | 3.0 (1.28) | 2.58 (0.90) | 0.10 |

| Q5. other vegetables? Include fresh and cooked vegetables, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods: Eggplant, tomato, pepper (e.g., green or red bell pepper), cucumber, onion, zucchini and beetroot. | 3.5 (1.09) | 4.42 (1.31) | 0.11 |

| Q6. citrus fruits? Include only whole fruit, not juices. Examples of foods in this group: Orange, grapefruit, tangerine, or other citrus fruit | 1.92 (1.0) | 2.92 (1.68) | 0.06 |

| Q7. deep orange fruits? Include fresh, frozen, canned, or thermally processed fruits, eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Include only whole fruit, not juices. Examples of foods: Mango, papaya, cantaloupe, apricot | 1.5 (0.80) | 1.58 (0.67) | 0.67 |

| Q8. other fruits? Include only whole fruit, not juices. Include fresh, frozen, or canned fruits. Examples of foods in this group: Apple, berries (e.g., strawberry, raspberry, blueberry), peach, plum, prune, grapes, avocado, pear or other fruits | 3.25 (1.06) | 4.08 (1.56) | 0.06 |

| Q9. beans, peas, and soy products? Include when eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods in this group: Beans (e.g., pinto, navy, black, kidney beans, edamame, soy milk, tofu, tempeh), peas (e.g., green peas, chickpeas, hummus. Exclude peanuts) and lentils (e.g., red lentil, brown lentil, yellow lentil, other) | 2.58 (1.08) | 3.42 (1.16) | 0.06 |

| Q10. nuts and seeds? Include when eaten separately or as part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods in this group: Nuts (e.g., peanut, walnut, almond, pecan, pistachio, mixed nuts), seeds (e.g., pumpkin, sesame, sunflower seeds, other seeds) or nut or seed butter (e.g., peanut or sesame butter/tahini, other) | 3.42 (1.44) | 3.5 (1.57) | 0.87 |

| Q11. poultry? Do NOT include luncheon meats, hot dogs, organ meat, chicken nuggets, luncheon meat, and pâté. Examples of foods in this group: Chicken, turkey, duck and other poultry | 2.83 (0.83) | 3.25 (1.22) | 0.27 |

| Q12. fish? Include fresh, frozen, or canned. Do NOT include fried fish. | 1.58 (0.79) | 2.5 (0.67) | <0.01 |

| Q13. red meat? Include muscle and organ meat as a main dish/as a part of a mixed dish. Examples of foods in this group: Beef, veal, lamb, goat, pork, other red meat | 2.5 (1.09) | 2.33 (1.07) | 0.17 |

| Q14. processed meats? Do NOT include very small quantities used for seasoning. Examples of foods in this group: Sausage, salami, bologna, pepperoni, ham, bacon, cured meat, beef jerky, corned beef, hot dog, frankfurter, chicken nuggets, canned meat | 2.5 (1.08) | 1.75 (0.62) | 0.04 |

| Q15. eggs? Include hen, duck, goose, or other poultry eggs. Examples of foods: Scrambled eggs, fried eggs, boiled eggs, quiche or similar egg-based dish | 2.58 (0.90) | 2.83 (0.83) | 0.28 |

| Q16. drink low-fat milk? Include products with 2% milk fat or less. Include only products made of animal milk. | 3.83 (2.37) | 4.08 (2.11) | 0.49 |

| Q17 *. full or whole-fat milk? Do NOT include ice cream, yogurt, or kefir. Include only products made of animal milk. | 1.42 (0.79) | 1.83 (1.19) | 0.14 |

| Q18 *. cheese? | 3.92 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.09) | 0.05 |

| Q19 *. fermented foods? Examples of foods: yogurt, kefir, kombucha, sauerkraut, kimchi | 1.83 (1.27) | 2.08 (1.51) | 0.63 |

| Q20. whole grains? Include cereals, porridges, pastas, breads, and baked goods containing at least 50% whole grain. Examples of foods in this group: Wholegrain bread or pasta, cereals (e.g., granola, muesli, Fiber 1, Kashi), plain popcorn, porridge (e.g., oatmeal, whole wheat, whole corn flour) or other whole grains (e.g., quinoa, amaranth, millet, brown rice, other) | 3.42 (1.51) | 4.17 (1.19) | 0.06 |

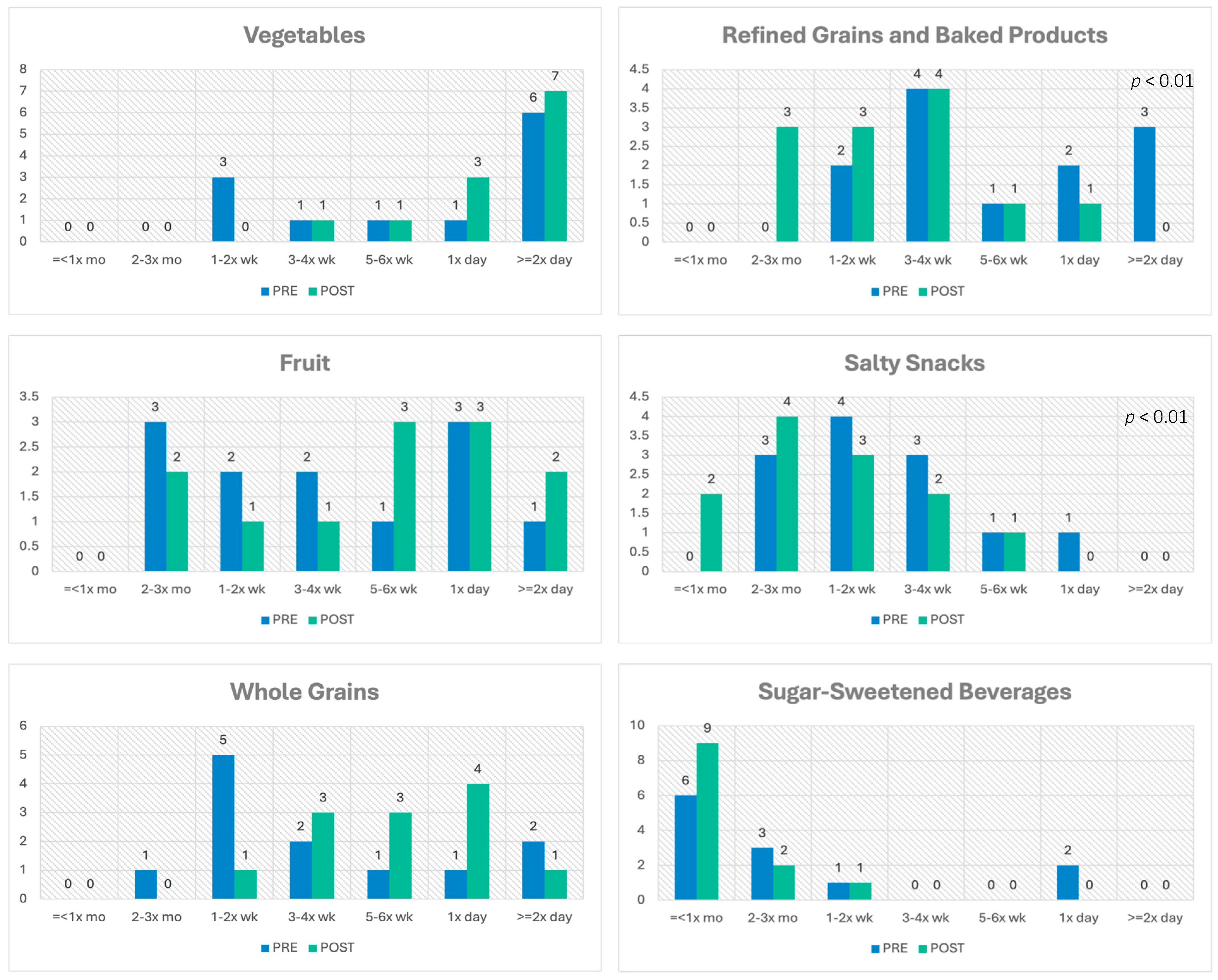

| Q21. refined grains and baked products? Examples of foods in this group: White bread, bagel, doughnut, bun or roll, white rice, couscous, noodles or pasta, pizza or pie crust, baked goods (e.g., pancake, cracker, waffle, muffin, tortilla, pita, matzo, naan), cereals (e.g., corn flakes, puffs, Chex cereal), Choco Pops, polenta | 5 (1.54) | 3.5 (1.24) | 0.01 |

| Q22 *. salty snacks? Examples of foods in this group: pretzels, potato chips, cheesy popcorn | 3.42 (1.24) | 2.67 (1.23) | 0.03 |

| Q23. sugar-sweetened beverages? Do NOT include coffee or tea, milk or cereal-based sugary drinks, homemade juices and diet drinks with artificial sugar. Examples of foods in this group: Sodas/soft drinks (e.g., Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Fanta, Sprite. Exclude diet sodas), energy drinks (e.g., Red Bull, Monster, and sport drinks with added sugar. Exclude sugar free drinks) and commercial fruit juices and fruit drinks with added sugar | 2.25 (1.86) | 1.33 (0.65) | 0.11 |

| Q24 *. alcoholic beverages? | 2.0 (0.95) | 1.92 (1.24) | 0.59 |

| Q25. sweets and ice cream? | 4.75 (1.60) | 3.67 (1.50) | 0.02 |

| Q26. fried foods? | 2.5 (1.09) | 2.08 (0.90) | 0.05 |

| Q27. [use] liquid oils in preparing your meals or seasoning salad? Do NOT include semisolid oils (e.g., palm and coconut oil) or solid fats | 3.83 (1.64) | 5.08 (1.38) | 0.01 |

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, E.J.; Mozaffarian, D.; Leung, C.W.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Murthy, V.L. Diet and Food and Nutrition Insecurity and Cardiometabolic Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1692–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean Diet and Health: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.-J.; Wang, F.; Korat, A.A.; Eliassen, A.H.; Chavarro, J.; Grodstein, F.; Li, J.; Liang, L.; Willett, W.C.; Sun, Q.; et al. Optimal Dietary Patterns for Healthy Aging. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Moore, L.V.; Park, S.; Harris, D.M.; Blanck, H.M. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Average Healthy Eating Index-2020 Scores for the U.S. Population—Total Ages 2 and Older and by Age Groups, WWEIA, NHANES 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cnpp/hei-scores-americans (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Houghtaling, B.; Short, E.; Shanks, C.B.; Stotz, S.A.; Yaroch, A.; Seligman, H.; Marriott, J.P.; Eastman, J.; Long, C.R. Implementation of Food Is Medicine Programs in Healthcare Settings: A Narrative Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 2797–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.J.; Rebholz, C.M. Adherence to the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and Other Dietary Patterns May Reduce Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Gardner, C.D.; Kendrick, K.B.; Seligman, H.K.; Yaroch, A.L.; Gomes, A.V.; Ivy, K.N.; Scarmo, S.; Cotwright, C.J.; Schwartz, M.B.; et al. Strengthening US Food Policies and Programs to Promote Equity in Nutrition Security: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e1077–e1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Rockefeller Foundation. The True Cost of Food. Measuring What Matters to Transform the U.S. Food System; The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deuman, K.; Callahan, E.; Wang, L.; Mozaffarian, D. The True Cost of Food: Food Is Medicine Case Study; Friedman School, Tufts University, Food is Medicine Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, J.; Sapp, C.; Janisch, K.; Adeyemo, M.A.; McClure, A.; Heredia, N.I.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Moin, T.; Malik, S.; Slusser, W.; et al. Improving Cooking Skills, Lifestyle Behaviors, and Clinical Outcomes for Adults at Risk for Cardiometabolic Disease: Protocol for a Randomized Teaching Kitchen Multisite Trial (TK-MT). Nutrients 2025, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downer, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Harlan, T.S.; Olstad, D.L.; Mozaffarian, D. Food Is Medicine: Actions to Integrate Food and Nutrition into Healthcare. BMJ 2020, 369, m2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWhorter, J.W.; Danho, M.P.; LaRue, D.M.; Tseng, K.C.; Weston, S.R.; Moore, L.S.; Durand, C.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Sharma, S.V. Barriers and Facilitators of Implementing a Clinic-Integrated Food Prescription Plus Culinary Medicine Program in a Low-Income Food Insecure Population: A Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 122, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghtaling, B.; Greene, M.; Parab, K.V.; Singleton, C.R. Improving Fruit and Vegetable Accessibility, Purchasing, and Consumption to Advance Nutrition Security and Health Equity in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Aspry, K.E.; Garfield, K.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Seligman, H.; Velarde, G.P.; Williams, K.; Yang, E. “Food Is Medicine” Strategies for Nutrition Security and Cardiometabolic Health Equity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Blanck, H.M.; Garfield, K.M.; Wassung, A.; Petersen, R. A Food Is Medicine Approach to Achieve Nutrition Security and Improve Health. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2238–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, E.K.; Stenmark, S.H.; DeBor, M.; Seligman, H.K. The Right to Food: Building Upon “Food Is Medicine”. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs Early, K.; Stanley, K. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: The Role of Medical Nutrition Therapy and Registered Dietitian Nutritionists in the Prevention and Treatment of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, K.; Cudhea, F.P.; Wong, J.B.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Downer, S.; Lauren, B.N.; Mozaffarian, D. Association of National Expansion of Insurance Coverage of Medically Tailored Meals With Estimated Hospitalizations and Health Care Expenditures in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2236898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Hill, C.; Ajayi, T.; Linsky, T.; Tishler, L.W.; DeWalt, D.A. Meal Delivery Programs Reduce The Use Of Costly Health Care In Dually Eligible Medicare And Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Randall, L.; Cranston, K.; Waters, D.B.; Hsu, J. Association Between Receipt of a Medically Tailored Meal Program and Health Care Use. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotz, S.A.; Budd Nugent, N.; Ridberg, R.; Byker Shanks, C.; Her, K.; Yaroch, A.L.; Seligman, H. Produce Prescription Projects: Challenges, Solutions, and Emerging Best Practices—Perspectives from Health Care Providers. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, A.; Gill, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Love, C.; Jernigan, V.B. The Effect of Food Prescription Programs on Chronic Disease Management in Primarily Low-Income Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Health 2022, 28, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, K.; Du, M.; Li, Z.; Mozaffarian, D.; Chui, K.; Shi, P.; Ling, B.; Cash, S.B.; Folta, S.C.; Zhang, F.F. Impact of Produce Prescriptions on Diet, Food Security, and Cardiometabolic Health Outcomes: A Multisite Evaluation of 9 Produce Prescription Programs in the United States. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e009520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Coyle, D.H.; Trieu, K.; Neal, B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Marklund, M.; Wu, J.H.Y. Healthy Food Prescription Programs and Their Impact on Dietary Behavior and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lauren, B.N.; Hager, K.; Zhang, F.F.; Wong, J.B.; Kim, D.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Health and Economic Impacts of Implementing Produce Prescription Programs for Diabetes in the United States: A Microsimulation Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Mozaffarian, D.; Sy, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wilde, P.E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Jardim, T.S.V.; Gaziano, T.A.; Micha, R. Cost-Effectiveness of Financial Incentives for Improving Diet and Health through Medicare and Medicaid: A Microsimulation Study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, R.; Guajardo, C.; Ilarraza, D.; Milgrom, N.; Pike, D.; Savoie, K.; Valbuena, F.; Miller-Matero, L.R. Participation in a Farmers’ Market Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program at a Federally Qualified Health Center Improves Hemoglobin A1C in Low Income Uncontrolled Diabetics. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpp, K.G.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Sharma, S.V.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Brewer, L.C.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Gardner, C.D.; Gervis, J.E.; Harrington, R.A.; Herrero, M.; et al. Food Is Medicine: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1417–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. The White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health—A New National Strategy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2014–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, R. Food Is Medicine Initiative for Mitigating Food Insecurity in the United States. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2024, 57, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, A.; Zurbau, A.; Gucciardi, E. The Effect of Food Is Medicine Interventions on Diabetes-Related Health Outcomes Among Low-Income and Food-Insecure Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Diabetes 2023, 47, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, N.I.; Stone, T.A.; Siler, M.; Goldstein, M.; Albin, J.L. Physician-Chef-Dietitian Partnerships for Evidence-Based Dietary Approaches to Tackling Chronic Disease: The Case for Culinary Medicine in Teaching Kitchens. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2023, 15, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, C.A. Addressing Social Determinants of Health via Food as Medicine Interventions to Improve Cardiometabolic Health. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e010319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.V.; McWhorter, J.W.; Chow, J.; Danho, M.P.; Weston, S.R.; Chavez, F.; Moore, L.S.; Almohamad, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Liew, E.; et al. Impact of a Virtual Culinary Medicine Curriculum on Biometric Outcomes, Dietary Habits, and Related Psychosocial Factors among Patients with Diabetes Participating in a Food Prescription Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, M.Y.; Kato, S.; Niki, A.; Hara, T.; Ozawa, H.; Ishibashi, C.; Hosokawa, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Fujishima, Y.; Nishizawa, H.; et al. Feasibility Pilot Study of a Japanese Teaching Kitchen Program. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1258434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munroe, D.; Moore, M.A.; Bonnet, J.P.; Rastorguieva, K.; Mascaro, J.S.; Craighead, L.W.; Haack, C.I.; Quave, C.L.; Bergquist, S.H. Development of Culinary and Self-Care Programs in Diverse Settings: Theoretical Considerations and Available Evidence. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 16, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, S.H.; Wang, D.; Fall, R.; Bonnet, J.P.; Morgan, K.R.; Munroe, D.; Moore, M.A. Effect of the Emory Healthy Kitchen Collaborative on Employee Health Habits and Body Weight: A 12-Month Workplace Wellness Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, D.; Urich, S.M.; Roberts, H.L. Effectiveness of a Teaching Kitchen Intervention on Dietary Intake, Cooking Self-Efficacy, and Psychosocial Health. Am. J. Health Educ. 2023, 54, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.A.; Cousineau, B.A.; Rastorguieva, K.; Bonnet, J.P.; Bergquist, S.H. A Teaching Kitchen Program Improves Employee Micronutrient and Healthy Dietary Consumption. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2023, 16, 11786388231159192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauber, Z.; Razavi, A.C.; Sarris, L.; Harlan, T.S.; Monlezun, D.J. Multisite Medical Student-Led Community Culinary Medicine Classes Improve Patients’ Diets: Machine Learning-Augmented Propensity Score-Adjusted Fixed Effects Cohort Analysis of 1381 Subjects. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 16, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, A.C.; Monlezun, D.J.; Sapin, A.; Stauber, Z.; Schradle, K.; Schlag, E.; Dyer, A.; Gagen, B.; McCormack, I.G.; Akhiwu, O.; et al. Multisite Culinary Medicine Curriculum Is Associated With Cardioprotective Dietary Patterns and Lifestyle Medicine Competencies Among Medical Trainees. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, A.C.; Sapin, A.; Monlezun, D.J.; McCormack, I.G.; Latoff, A.; Pedroza, K.; McCullough, C.; Sarris, L.; Schlag, E.; Dyer, A.; et al. Effect of Culinary Education Curriculum on Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Food Cost Savings in Families: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Public. Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2297–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlezun, D.J.; Kasprowicz, E.; Tosh, K.W.; Nix, J.; Urday, P.; Tice, D.; Sarris, L.; Harlan, T.S. Medical School-Based Teaching Kitchen Improves HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Results from a Novel Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 109, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaracco, C.; Thomas, O.W.; Massa, J.; Bartlett, R.; Eisenberg, D.M. Characteristics of Current Teaching Kitchens: Findings from Recent Surveys of the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, K.; Hajna, S.; Joseph, L.; Da Costa, D.; Christopoulos, S.; Gougeon, R. Effects of Meal Preparation Training on Body Weight, Glycemia, and Blood Pressure: Results of a Phase 2 Trial in Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Righter, A.C.; Matthews, B.; Zhang, W.; Willett, W.C.; Massa, J. Feasibility Pilot Study of a Teaching Kitchen and Self-Care Curriculum in a Workplace Setting. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.M.; Bernardo, G.L.; Fernandes, A.C.; Geraldo, A.P.G.; Hauschild, D.B.; Venske, D.K.R.; Medeiros, F.L.; Proença, R.P.D.C.; Uggioni, P.L. Impact of a Cooking Intervention on the Cooking Skills of Adult Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, L.; Thomas, O.; Imamura, A.; MacLaren, J.; McClure, A.; Khalil, J.; Massa, J. Will a Programmatic Framework Integrating Food Is Medicine Achieve Value on Investment? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Thompson, W.G.; Almasri, J.; Wang, Z.; Lakis, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Hensrud, D.D.; Frie, K.S.; Wirtz, M.J.; Murad, A.L.; et al. The Effect of Culinary Interventions (Cooking Classes) on Dietary Intake and Behavioral Change: A Systematic Review and Evidence Map. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, L.; Koch, P.A.; Liu, A.; Galitzdorfer, L.; Costa, A.; Utter, J. Experiential Features of Culinary Nutrition Education That Drive Behavior Change: Frameworks for Research and Practice. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inf. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)--a Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2008, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Dedoose Cloud Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data (2023). Available online: https://dedoose.com (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Teaching Kitchen Collaborative. Available online: https://teachingkitchens.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Eisenberg, D.M.; Pacheco, L.S.; McClure, A.C.; McWhorter, J.W.; Janisch, K.; Massa, J. Perspective: Teaching Kitchens: Conceptual Origins, Applications and Potential for Impact within Food Is Medicine Research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard, T.H. Chan School of Public Health The Nutrition Source. Available online: https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Medical Outcomes Study: 20-Item Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-20). Available online: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/20-item-short-form/survey-instrument.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Stewart, A.L.; Hays, R.D.; Ware, J.E.J. The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey. Reliability and Validity in a Patient Population. Med. Care 1988, 26, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonacchi, A.; Chiesi, F.; Lau, C.; Marunic, G.; Saklofske, D.H.; Marra, F.; Miccinesi, G. Rapid and Sound Assessment of Well-Being within a Multi-Dimensional Approach: The Well-Being Numerical Rating Scales (WB-NRSs). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Ishikawa, Y.; Hosokawa, C.; Janisch, K.; Massa, J.; Eisenberg, D.M. Gender Differences in Global Estimates of Cooking Frequency Prior to COVID-19. Appetite 2021, 161, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Engelhard, E.E.; Crumbaugh, A.S.; Seligman, H.K. Brief Assessment of Food Insecurity Accurately Identifies High-Risk US Adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, E.R.; Quigg, A.M.; Black, M.M.; Coleman, S.M.; Heeren, T.; Rose-Jacobs, R.; Cook, J.T.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.A.; Casey, P.H.; Chilton, M.; et al. Development and Validity of a 2-Item Screen to Identify Families at Risk for Food Insecurity. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e26–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrasky, M.D.; Williams, J.E.; Catalano, P.M.; Griffin, S.F. Development of Psychosocial Scales for Evaluating the Impact of a Culinary Nutrition Education Program on Cooking and Healthful Eating. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, K.L.; Wrieden, W.L.; Anderson, A.S. Validity and Reliability of a Short Questionnaire for Assessing the Impact of Cooking Skills Interventions. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronsteiner-Gicevic, S.; Mou, Y.; Bromage, S.; Fung, T.T.; Willett, W. Development of a Diet Quality Screener for Global Use: Evaluation in a Sample of US Women. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 854–871.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Framson, C.; Kristal, A.R.; Schenk, J.M.; Littman, A.J.; Zeliadt, S.; Benitez, D. Development and Validation of the Mindful Eating Questionnaire. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, K.J.; Ngor, E.; Reynolds, K.; Quinn, V.P.; Koebnick, C.; Young, D.R.; Sternfeld, B.; Sallis, R.E. Initial Validation of an Exercise “Vital Sign” in Electronic Medical Records. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 2071–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurses Healthy Study II Questionnaire. Available online: https://nurseshealthstudy.org/sites/default/files/2021%20long.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Yu, L.; Buysse, D.J.; Germain, A.; Moul, D.E.; Stover, A.; Dodds, N.E.; Johnston, K.L.; Pilkonis, P.A. Development of Short Forms from the PROMISTM Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment Item Banks. Behav. Sleep. Med. 2012, 10, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph, M.J.; Larson, N.; Laska, M.N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Nutrition Facts Panels: Who Uses Them, What Do They Use, and How Does Use Relate to Dietary Intake? J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Tucker, A.C.; Leung, C.W. Greater Frequency of Cooking Dinner at Home and More Time Spent Cooking Are Inversely Associated With Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Among US Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1590–1605.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irl, B.H.; Evert, A.; Fleming, A.; Gaudiani, L.M.; Guggenmos, K.J.; Kaufer, D.I.; McGill, J.B.; Verderese, C.A.; Martinez, J. Culinary Medicine: Advancing a Framework for Healthier Eating to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Prevention. Clin. Ther. 2019, 41, 2184–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, E.S.; Patnode, C.D.; Webber, E.M.; Redmond, N.; Rushkin, M.; O’Connor, E.A. Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Weight Loss Interventions to Prevent Obesity-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018, 320, 1172–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Selected Quote |

|---|---|

| Goals | |

| I am not a good cook and … I saw it as a good opportunity to learn, which I learned a lot. | |

| I have … kids and I need to be around for a while. | |

| I just wanted to learn how to get more vegetables in my diet [and] different ways to cook vegetables. | |

| Behavior change | |

| I think I am more conscious when it comes to actually reading labels and choosing what I need. | |

| I actually think I found myself cooking more. | |

| I cannot wait to make a veggie tray. That is part of my weekly staple, if not once, twice, three, four times a week, or I learned how to utilize leftovers in a unique way, whether I make soup or something else, or add it to a salad, or add a few greens to it, which I never ever would have done before. | |

| Challenges | |

| I would have to figure out how to position [the] tablet that I was using, so that you could see what I was doing when I was cooking [which] was kind of difficult. | |

| It was hard because you didn’t really get to know your peers … the other participants in class. | |

| The hard thing was people would start talking and then you all had to be quiet and then wait for, you know, and it was just zoom, zoom is hard to do. | |

| Logistics feedback | |

| The only thing … that was hard for me was just making sure that I was picking up the food. | |

| It was just so peaceful being by myself in my own kitchen, setting everything up, not worrying about anything else and then waiting for the class to start. | |

| Overall impression, I mean you guys did a fantastic job. It was well organized, [and] the time management was fantastic. | |

| Content feedback | |

| Definitely the nutrition piece [was the most helpful], I can’t even speak more highly of all that and then bringing the mindfulness into it and tips and suggestions on how to prepare [by] watching the preparation of something. | |

| There were so many new things that I did learn, so many tricks, and putting it all together with the mindfulness, with the culinary skills and everything. It worked together perfectly. | |

| I think it was helpful to watch [the chef] demo how to put the meal together rather than just following exactly down the recipe. I thought that was just fun. [Chef’s] tips were great. And I think it was nice to hear other people’s inputs on their experiences or stories or how they did things. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McClure, A.C.; Fenn, M.; Lebby, S.R.; Mecchella, J.N.; Brilling, H.K.; Finn, S.H.; Dovin, K.A.; Chinburg, E.; Massa, J.; Janisch, K.; et al. A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111854

McClure AC, Fenn M, Lebby SR, Mecchella JN, Brilling HK, Finn SH, Dovin KA, Chinburg E, Massa J, Janisch K, et al. A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111854

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcClure, Auden C., Meredith Fenn, Stephanie R. Lebby, John N. Mecchella, Hannah K. Brilling, Sarah H. Finn, Kimberly A. Dovin, Elsa Chinburg, Jennifer Massa, Kate Janisch, and et al. 2025. "A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111854

APA StyleMcClure, A. C., Fenn, M., Lebby, S. R., Mecchella, J. N., Brilling, H. K., Finn, S. H., Dovin, K. A., Chinburg, E., Massa, J., Janisch, K., Eisenberg, D. M., & Rothstein, R. I. (2025). A Culinary-Based Intensive Lifestyle Program for Patients with Obesity: The Teaching Kitchen Collaborative Curriculum (TKCC) Pilot Study. Nutrients, 17(11), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111854