Analysis of Blame, Guilt, and Shame Related to Body and Body Weight and Their Relationship with the Context of Psychological Functioning Among the Pediatric Population with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

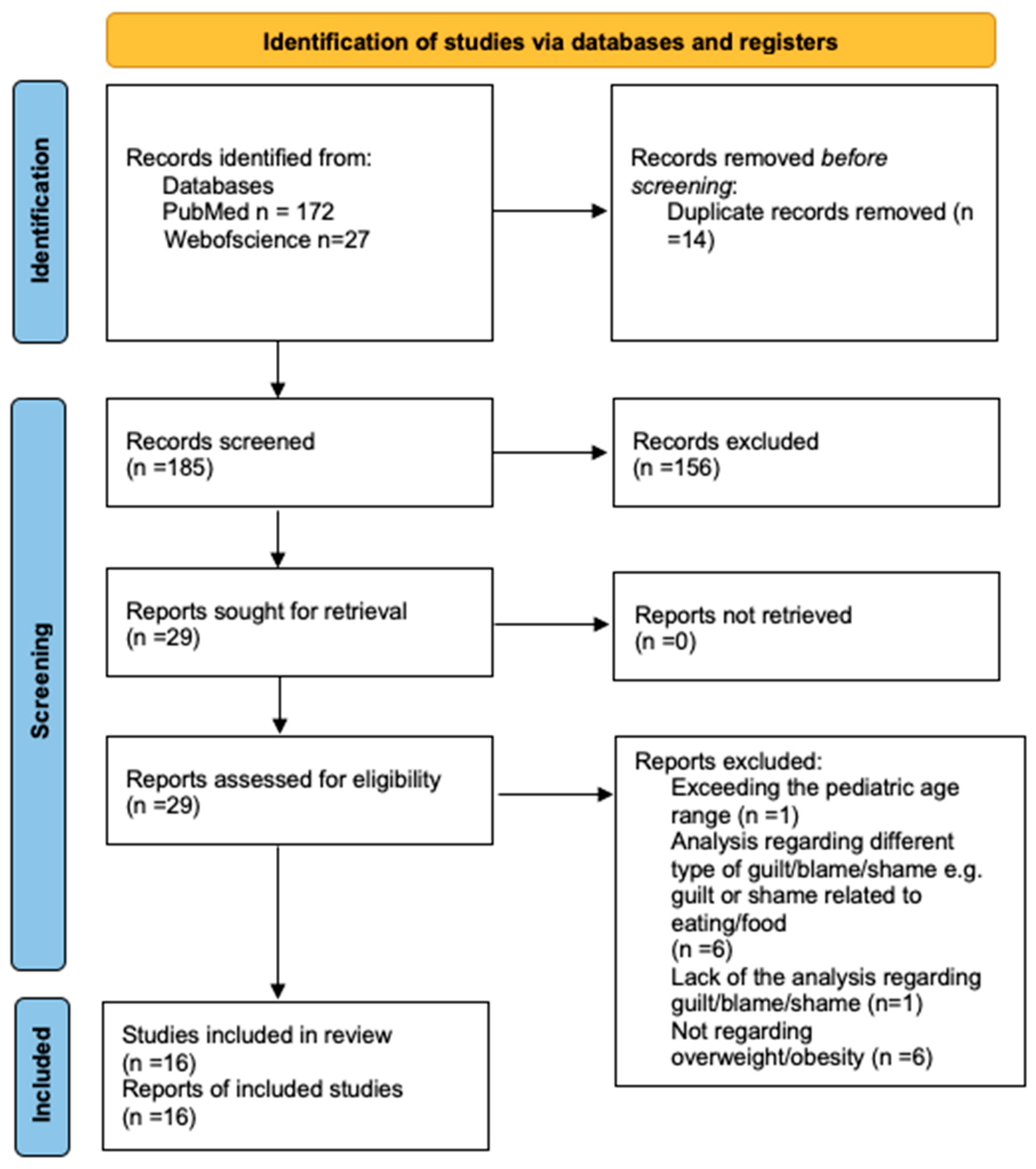

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Question

2.2. Finding Studies

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

| Authors, Year and Region | Design | Participants | Sex and Age | Variables | Methods | Outcomes 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iannaccone et al., 2016 [38] Italy | quantitative study | N = 222 NO = 111 NNW = 111 Students from public high schools in Southern Italy O: BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age | O: female = 43 (the rest are men) NW: female = 43 (the rest are men) 13–19 years old | * Parental bonding * Self-esteem * Shame * Perfectionism * Eating disturbance | * The Parental Bonding Instrument * The Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale * The Experience of Shame Scale * The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale * Eating Disorder Risk Composite | O: bodily shame is significantly associated with ED risk. O: bodily shame was a significant predictor of ED risk, showing a positive relationship in the mediation model, O: self-esteem was a significant predictor of bodily shame, demonstrating a negative relationship in the mediation model |

| Øen et al., 2018 [10] Norway | qualitative study | NO = 5 Adolescents who have contact with healthcare professionals about obesity O: >30-isoBMI | 80% female 12–15 years old | * Experiences in everyday life with obesity * Sense of condition * Challenges and motivation for changing behavior * Experience health-care encounters | Individual in-depth interviews (a semi-structured interview guide) | * Three key themes emerged regarding obesity: (1) a multi-faceted and challenging condition to address; (2) a source of shame and vulnerability; (3) a factor contributing to bullying and fragile social relationships. * Lack of support from parents, trusted friends, and healthcare providers—as well as experiences of bullying, shame, guilt, and self-blame—posed significant threats, reducing motivation for seeking help and making successful lifestyle changes. * The girls in our study expressed low self-confidence and self-esteem, with most interviewees reporting feelings of shame and self-blame. These emotions appeared to heighten their sense of hopelessness and acted as barriers to seeking help and implementing lifestyle changes. * A prominent theme in the interviews was the deep sense of shame young people felt about their condition and their struggle to discuss obesity-related issues with others. Despite this difficulty, they clearly expressed a need to talk about their weight concerns. They wished for others to take their struggles more seriously and were distressed by how their condition was sometimes discussed. * Support providers should avoid placing excessive demands on weight loss, as adolescents feared failure. Unrealistic expectations could intensify their feelings of shame, responsibility, and the potential loss of support. |

| Orvidas et al., 2020 [19] United States | mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative study) | T0: N = 9 T1: N = 48 T0 (intervention development): 6 undergraduate students and 3 children (8 years old) T1 (intervention testing): youth with obesity O: BMI ≥ 95th percentile | T0: NI T1: 54.17% female T0: 8–18 years old T1: 9–17 years old | * Mindsets of health * Self-efficacy * Value of health behaviors * Perceived primary control scale for children—health behaviors * Self-blame * Body dissatisfaction | * 4-item scale for mindsets of health * 10-item scale for self-efficacy * 9-item for value of health behaviors * The Perceived Control Scale for Children - adapted this measurement scale to health-related statements * Two separate prompts: “How responsible are you personally for your health? That is, how much do you feel that your health is a result of choices you make, rather than something you can’t control?”, “How responsible are you personally for your body weight? That is, how much do you feel that your body weight is a result of choices you make, rather than something you can’t control?”. * Two items from the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire to measure body dissatisfaction: “How dissatisfied have you felt about your weight?” and “How dissatisfied have you felt about your shape?” * Three writing activities related to growth themes | * Blame was positively correlated with perceived control and intrinsic value, while self-efficacy was positively correlated with intrinsic value. * At post-test, a growth mindset of health was positively correlated with self-efficacy, perceived control, and blame, all of which were also positively correlated with each other. * Growth mindsets related to health and health behavior cognitions (including nutrition and exercise self-efficacy and perceived control) increased significantly. However, despite efforts to reduce feelings of culpability, blame also increased from pre-test to post-test. * Contrary to expectations and previous research, participants reported significantly more blame for their current body weight at post-test compared to pre-test. |

| Brewis et al., 2018 [39] United States | quantitative study | Nbaseline = 1443 N = 362 completed all four rounds of data collection College students living in first-year residence halls at a single university (Arizona State University) O: BMI ≥ 30 | 64.6% female at baseline 71.5% female after all four rounds of data collection first-year (freshman; no other information on the age of the participants) | * Depressive symptom levels * Body shame * Openness to friendship | * American College Health Association validated protocols— depressive symptom levels * Question about body shame from Vartanian and Shaprow’s study (2008) * Ten statements reflecting openness to friendship | * Students with overweight or obesity had higher mean levels of body shame compared to normal-weight students (Phase 1—early fall). * Students with overweight or obesity who did not experience body shame had lower mean depression scores compared to those with overweight or obesity who did experience body shame. |

| Puhl and Himmelstein, 2018 [40] United States | quantitative study | N = 148 O: 34.5% OV: 37.2% Adolescents enrolled in a national weight loss camp OV: BMI = 85th to <95th percentile O: BMI ≥ 95th percentile | 50% female 13–18 years old | * Perceptions of parental use of words to describe body weight * Parental comments about weight * Experienced weight stigma from family members * Internalized weight stigma | * 18 words describing body weight (+ for each word, adolescents could select whether parental use other word made them feel “sad”, “embarrassed” and/or “ashamed”, “not sure”, “fine, it doesn’t bother me” or “my parent(s) does not use this word.”) * How often does your mother [father] make comments to you about your weight? * Adolescents were asked a yes/no question to indicate whether or not their family members had teased or treated them unkindly because of their weight. * Weight Bias Internalization Scale | * Similarly, over 40% of adolescents reported feeling shame when parents referred to their body weight using terms like “fat”, “higher body weight”, “large”, “high BMI”, or “big.” * Table 3 [40] shows that words such as “large” (46.9%), “higher body weight” (46.9%), and “high BMI” (46%) were most commonly associated with feelings of “ashamed.” |

| Puhl et al., 2017 [33] United States | quantitative study | N = 50 Adolescents enrolled in a commercial summer weight-loss camp (Wellspring Academies) in 2016 O: BMI ≥ 95th percentile | 54% female M = 17.28 ± 2.62 years old | * Weight-based language preferences among adolescents | * 16 words used to describe excess body weight (“If your parent(s) use any of the following words to talk about your weight, how does it make you feel?”, resp. “sad”, “embarrassed”, “ashamed”, “not sure”, or “fine, it doesn’t bother me.”) | * A large proportion of participants, particularly girls, reported feeling sadness, shame, and embarrassment when parents used certain words to describe their body weight, highlighting the importance of considering the emotional impact of weight-based terminology. * For both males and females, approximately 30% felt ashamed when parents described their weight as “obese”. * Table 2 [33] shows the emotional responses of males and females to parents using various words to describe their body weight. The five words most often associated with “ashamed” were: “ashamed” (m: 30.4%, f: 29.6%), “heavy” (m: 26.1%, f: 22.2%), “big” (m: 21.7%, f: 29.6%), “overweight” (m: 21.7%, f: 29.6%), and “weight problem” (m: 17.4%, f: 40.7%). * Our findings suggest that adolescents may react to weight-based terminology in ways that induce emotional distress. A significant percentage of adolescents, particularly females, reported feeling sad, embarrassed, and ashamed in response to parental use of certain words regarding their body weight. |

| Roberts et al., 2021 [6] United States | qualitative study | Nparent = 19 Nadolescent = 12 Adolescents with severe obesity and their parents who attend a paediatric weight management O: BMI ≥ 120th percentile of the 95th percentile of BMI for age and sex | Parent: 89.47% female 30–54 years old Adolescent: 41.67% female 12.2–16.8 years old | * Experiences of weight stigma in adolescents with severe obesity and their parents | * A secondary analysis on 31 transcripts from a larger study of 46 transcripts conducted between February 2019 and June 2020 (semi-structured interviews) | * Four common themes emerged in experiences of weight stigma: weight-based teasing and bullying, interactions with healthcare providers (HCPs), family interactions, and blame. Subthemes included perceptions of fairness and the impact on mental health. * Blame is defined as the internal attribution of weight gain to oneself or one’s adolescent, as well as experiences of being blamed by others (e.g., parents, healthcare providers, or spouses) for the adolescent’s weight. * In describing their interactions with healthcare providers (HCPs) at the pediatric weight management (PWM) clinic, most adolescents and parents reported primarily positive and supportive experiences. However, some parents and adolescents felt that certain interactions made them feel “nervous”, as if their weight was “my fault” or that their efforts to change their eating and physical activity habits were not “good enough.”. Adolescents sometimes perceived that they were “getting into trouble”, which led to feelings of anxiety and personal blame for their weight. Similarly, parents reported feeling defensive and blamed for their actions, which they believed influenced their adolescent’s weight. * Negative interactions and the consequences of stigma often led adolescents and parents to internalize blame for the child’s weight or weight gain. Additionally, they reported feeling blamed by others, including parents, healthcare providers, and spouses. * Adolescents primarily blamed themselves for their weight, often attributing it to their own actions or eating habits. A 12-year-old boy (C5) shared, “…and it is my fault [long pause and looks down] for the weight gain.” In some cases, adolescents also assigned blame to others. A 14-year-old girl (C15) expressed frustration toward her mother for purchasing unhealthy food, stating, “I’d eaten it [the cake], so my mother yelled at me. But she bought it, so she can’t really yell at me… If they wouldn’t buy ice cream, I wouldn’t eat the ice cream… That doesn’t make sense.” * Parents expressed a sense of blame for their adolescent’s weight, using phrases such as “It’s all on me”, “It’s my responsibility”, and “It’s my fault.” Many also described feeling as though they had failed their adolescent. * A mother (P2) of a 12-year-old boy, struggling with how to help her son, expressed her frustration: “Why can’t I fix this? …I feel like we failed him in some way. How did we get this far?” * Parents reported feeling blamed by both spouses and healthcare providers (HCPs), who directly attributed responsibility to them for purchasing groceries and preparing meals at home. Blame from HCPs left parents feeling discouraged and misunderstood, while blame from spouses created tension between partners. Many mothers, in particular, described feeling overwhelmed by the heavy burden of managing their own work, daily household responsibilities, and the primary responsibility for their child’s weight management. These ongoing experiences compounded feelings of blame and household stress over the years. One mother of a 16-year-old girl (P1) described the constant pressure of daily weight management: “It’s all on me. It is my responsibility.” Another mother (C14) of a 13-year-old girl—who works seven days a week and whose husband has health issues— shared her frustration: “It’s my fault, but they don’t realize how much I have to do at the house, whether it’s the laundry and the dishes, and I’m working all day.” |

| Rosenberger et al., 2007 [11] United States | mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative study) | N = 174 Bariatric surgery candidates O: (NI) | 75% female M = 42.9 ± 11.1 years old (analyzing childhood history) | * Childhood history of being negatively teased (i.e., being made fun of) about weight * Psychiatric History * Weight and eating concerns * Psychological functioning | * The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV * Additional semi-structured interview * Childhood Weight, Dieting, and Teasing History: participants were asked the extent to which they were teased about weight as a child, rated using a 5-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’ * The Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire * The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale * The Beck Depression Inventory * The Body Shape Questionnaire * The Internalized Shame Scale | * Comparison of weight history and current functioning between groups with and without a history of teasing: - Participants with a history of teasing reported significantly higher concerns related to ED (EDE-Q eating, weight, and shape concerns). However, they did not differ significantly in terms of binge eating frequency or dietary restraint. Additionally, participants who experienced childhood teasing had significantly lower self-esteem and higher scores for depression, body dissatisfaction, and shame, even after controlling for the childhood onset of obesity. - The present study also found that shame, a dimension of psychological functioning reflecting internal feelings of worthlessness and inadequacy, is significantly associated with a history of teasing. - Finally, although the two groups did not differ significantly in rates of lifetime or current psychiatric disorders, bariatric surgery candidates with a history of teasing reported significantly lower self-esteem and significantly higher levels of depression and shame. Since these findings persist even after controlling for childhood onset of obesity, it suggests that the association between teasing history and current functioning is not simply due to an earlier age of obesity onset. |

| Sjöberg et al., 2005 [41] Sweden | quantitative study | N = 4703 O: 2.79% PreO: 13.72% Adolescent who answered the Survey of Adolescent Life in Vestmanland 2004 O and PreO: The international age- and gender-specific BMI cutoff points for children developed by the Childhood Obesity Working Group of the International Obesity Task Force14 were used to define subjects as normal weight, overweight (preobese), or obese. These cutoff points were derived from the data of a number of large international cross-sectional growth-study surveys. Cutoff points were determined through centile curves that at 18 years were drawn through the widely accepted cutoff points, 25 and 30 kg/m2, for adult overweight and obesity, respectively. | 49.18% female 15–17 years old | * Depressive symptoms and depression * Shame and psychosocial and economic status | * A self-rating scale (Depression Self-Rating Scales) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition * Shame index: Have you during the latest period of 3 months experienced that someone: 1. treated you in a degrading manner? 2. made fun of you in front of others? 3. questioned your sense of honor? 4. talked about you in a degrading manner? 5. ignored you or behaved as if you did not exist? * A family-economy index: Whether the family owned a computer; had Internet access; owned a house in the country for leisure activities; owned a boat big enough to sleep in; owned a caravan; or used to go for vacations in foreign countries and go alpine skiing on vacations. * The survey also included questions regarding parental separation and parental employment. | * Obesity was also significantly associated with experiences of shame. * All significant associations between BMI grouping and depression disappeared when shaming experiences, parental employment, and parental separation were controlled for. * Adolescents who reported frequent experiences of shame had an increased risk of depression. |

| Tan et al., 2018 [42] China | quantitative study | NNM = 1021 NOV = 700 NO = 321 Adolescents with normal weight, overweight status, and obese status from middle schools in urban areas located across seven geographic districts in China OV and O: The cutoff points for BMI for overweight and obesity in the Chinese BMI reference conducted by the Group of China Obesity Task Force (GCOTF) | NM: 71.50% male OV: 71.43% male O: 71.65% male NM: 11–20 OV: 11–20 O: 11–19 | * Cognitive emotion regulation | * Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire | * Adolescents in the obesity group scored the highest on self-blame and rumination among the three groups. They also scored lower on acceptance, positive refocusing, and positive reappraisal compared to those in the normal weight group. * Higher scores on self-blame and rumination were associated with a higher BMI, while greater acceptance and positive refocusing were linked to a lower BMI. |

| Williams et al., 2008 [32] United States | qualitative study | N = 16 children with parents OV: 31% described themselves as “overweight” Ninth grade students in four high schools throughout West Virginia OV and O: NI (Healthy weight was also defined as a number on the scales that should be proportionate to one’s height. This number was defined by expert opinions, such as those conveyed by their healthcare providers or other accepted standards, such as BMI.) | Children: 44% male 14–18 years old Parents: NI | * Cultural perceptions of a healthy weight | * Separate focus group interviews were conducted concurrently with adolescent and parents or caregivers to identify the cultural perceptions of a healthy weight. Questions were developed using grounded theory to explore how a healthy weight was defined, what factors dictate body weight, the perceived severity of the obesity issue, and the social or health ramifications of the condition. | * Female participants were more concerned with their weight than males, with some expressing concerns that bordered on obsession. Both males and females described experiencing social stigma associated with overweight. * Students, particularly females, expressed various psychological consequences of overweight, including feelings of guilt and diminished self-esteem. Additionally, a reduced sense of belonging among peers and family was perceived as a consequence of obesity. |

| Moreira and Canavarro, 2017 [37] Portugal | quantitative study | N = 153 children/adolescents with overweight or obesity Adolescents with overweight/obesity followed in individual nutrition consultations OV: BMI between the 85th and the 95th percentile O: BMI equal or above the 95th percentile | 62.7% female 8–18 years old | * Mindfulness * Body shame * Quality of life | * The Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure * the body shame subscale of the Experience of Shame Scale * Portuguese child-report version of KIDSCREEN-10 index | * A strong negative correlation was found between mindfulness and body shame, as well as between quality of life and body shame in the full sample. * A negative correlation was found between mindfulness and body shame, as well as between body shame and quality of life in girls. In boys, a negative correlation was observed between mindfulness and body shame. * The moderated mediation analyses revealed that the path from body shame to quality of life was moderated only by gender. Specifically, while the interaction between body shame and gender was statistically significant, the interaction between body shame and age was not. Simple slope analyses demonstrated that an increase in body shame was associated with a decrease in quality of life only in girls. |

| Morinder et al., 2011 [9] Sweden | qualitative study | NO = 18 Adolescents with obesity from a pediatric obesity clinic in Sweden O: Classified as obesity according to the international age- and gender-specific BMI cutoff points established by the International Obesity Task Force | 66.67% female 14–16 years old | * semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions | * Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions (the questions focused on three areas: the participant’s perceptions and understandings of obesity and weight loss, referral to the paediatric obesity clinic, participation in obesity treatment) | * Regular clinic visits require sacrifices from parents, such as arranging transportation and taking time off from work, which can reinforce feelings of guilt. Shame and guilt are also mentioned when parents are held responsible for unsuccessful treatment outcomes. * Registration and treatment result in constant focus on body weight. When weight loss is not achieved, feelings of shame, failure, and disappointment arise. * Weight gain prompts feelings of embarrassment and shame. In such cases, individuals may avoid confrontation, often leading to missed appointments. This avoidance reinforces feelings of failure and guilt. As one participant shared: “I felt ashamed… because you said you would lose weight, but instead, you gained… I felt a bit embarrassed… and you could be sort of scared, like… (IP 9).” |

| Gouveia et al., 2018 [43] Portugal | quantitative study | N = 572 dyads (mother or father and adolescent) Adolescent: OV and O: 43.5% Sample collected in three public school units and three pediatric public hospitals in the central region of Portugal OV and O: BMI ≥ 85th percentile according to the WHO Child Growth Standards | Adolescent: 59.09% fame 12–18 years old Mother/father: 77.8% female 30–61 years old | * Mindful Parenting * Self-compassion * Body shame * Emotional eating | * Portuguese version of IMP Scale * The Self-Compassion Scale * the body shame subscale of the Experience of Shame Scale * the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire | * Adolescents with overweight/obesity undergoing nutritional treatment exhibited higher levels of body shame compared to those not undergoing treatment and those with normal weight. * Adolescents with overweight/obesity not undergoing nutritional treatment exhibited higher levels of body shame compared to adolescents with normal weight. * Mindful parenting, particularly the dimension of compassion for the child, was indirectly associated with emotional eating through adolescents’ self-compassion. This association was mediated sequentially by both self-compassion and body shame. Specifically, both adolescent boys and girls with higher levels of self-compassion had lower levels of emotional eating, and this relationship was mediated by reduced body shame. * Adolescents’ body shame was significantly and negatively correlated with mindful parenting and self-compassion, while body shame was significantly and positively correlated with emotional eating. |

| Giles et al., 2023 [16] Canada | qualitative study | NO = 5 5 children with spina bifida (SB) and 5 of their parents Children with SB and their parents recruited from outpatient multidisciplinary specialized SB clinics at two urban academic children’s hospitals in Canada. O: children who had previously discussed their weight with a healthcare provider at their SB clinic | 60% female 10–16 years old | * semi-structured, individual interviews | * Semi-structured, individual interviews conducted in-person and via videoconference. Sample interview questions for children: 1. What do you think it means to be healthy, and what it means to be unhealthy? 2. Tell me about a time when something happened that made you feel good about your body? 3. Who talks to you about things to do with your health? What do you talk about? 4. Do you ever talk about things like food or exercise or weight when you see your doctor or nurse? How does that make you feel? 5. What is the best thing doctors or nurses can do to help keep you healthy? Sample interview questions for parents: 1. What do you think it means for your child to be healthy, and unhealthy? 2. Who talks to your child about things to do with their health? 3. What have been your experiences of speaking with healthcare providers about your child’s weight? 4. How does your child feel about discussing their health? Their weight? 5. Do you and/or your child ever talk about things like food or physical activity or weight with healthcare professionals? How do you/your child feel? 6. What are the most important things to consider when designing weight management/healthy behaviour supports/services for children with spina bifida? | Embarrassment and guilt * Two of the girls reported feeling embarrassed and guilty when discussing weight with a healthcare provider: “I feel like I’m not doing enough [physical activity and eating healthy] and that I should, like, try to do more.” |

| Darling et al., 2023 [13] USA | qualitative study | N = 11 Pediatric medical providers in the New England area that refer adolescents to outpatient weight management (WM) interventions. Providers were eligible to participate if they self-identified as primarily treating adolescents and reported that at least one-third of their patient population was from a low-income background (per provider report using public insurance as a proxy for income). O: NI | 82% female M = 45.9 ± 10.3 years old | * semi-structured individual interviews | * Semi-structured individual interviews—three main topic areas: (1) experiences working with adolescents from low-income backgrounds, (2) perceptions of interactions concerning WM, and (3) barriers and facilitators to WM engagement. | * In addition to general hesitation and logistical barriers to engaging in weight management (WM), many providers also reported that adolescents and caregivers may experience guilt or shame related to the need for a referral to WM. * Providers perceive that these experiences of shame often hinder a family’s likelihood of seeking further treatment. For instance, one provider (male, MD, 54 years old) stated, “There is a lot of guilt associated with weight and weight gain… not just from the child’s perspective, but also from the parent’s perspective as well.” * Providers described significant shame associated with high weight. They often reported that adolescents experience stigma related to their weight both at home and at school, making it particularly emotional to discuss in the medical office. * Nearly all providers discussed techniques they use to reduce stigma around weight, primarily by decreasing the focus on weight and increasing the emphasis on health behaviors. * Providers also emphasized the importance of supporting adolescents’ own health priorities, rather than focusing on caregivers’ goals. For example, one provider (female, MD, 56 years old) explicitly highlighted family responses to these terms, stating, “It can still feel shaming for kids and teens when I’m telling them I’m worried about their weight– that they’re at an unhealthy weight.” * Overall, providers focused on improving communication and minimizing the negative impacts of weight-related discussions, while acknowledging the tension created by the weight-related health outcomes they observe in patients. * Despite this, providers sometimes used language to describe weight status that could be interpreted as blaming or shaming toward adolescents and caregivers. For example, one provider (female, MD, 55 years old) described caregivers, saying, “They don’t take responsibility for the changes… how do you get the parents to take responsibility?” |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ED | Eating disorders |

| IP | Interviewed person |

| N | Number |

| NI | No information |

| NM | Normal weight |

| O | Obesity |

| OV | Overweight |

| PreO | Preobesity |

| SB | Spina bifida |

| WM | Weight management |

References

- Amiri, S.; Behnezhad, S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatrie 2019, 33, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviantony, F.; Fitria, Y.; Rondhianto, R.; Pramesuari, N.K.T. An in-depth review of body shaming phenomenon among adolescents: Trigger factors, psychological impact and prevention efforts. S. Afr. J. Psychiatr. 2024, 30, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmer, C.; Bosnjak, M.; Mata, J. The association between weight stigma and mental health: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokka, I.; Mourikis, I.; Bacopoulou, F. Psychiatric disorders and obesity in childhood and adolescence—A systematic review of cross-sectional studies. Children 2023, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Golboni, F.; Griffiths, M.D.; Broström, A.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Weight-related stigma and psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.J.; Polfuss, M.L.; Marston, E.C.; Davis, R.L. Experiences of weight stigma in adolescents with severe obesity and their families. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4184–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberga, A.S.; Pickering, B.J.; Hayden, K.A.; Ball, G.D.C.; Edwards, A.; Jelinski, S.; Nutter, S.; Oddie, S.; Sharma, A.M.; Russell-Mayhew, S. Weight bias reduction in health professionals: A systematic review. Clin. Obes. 2016, 6, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity 2009, 17, 941–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morinder, G.; Biguet, G.; Mattsson, E.; Marcus, C.; Larsson, U.E. Adolescents’ perceptions of obesity treatment—An interview study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øen, G.; Kvilhaugsvik, B.; Eldal, K.; Halding, A.G. Adolescents’ perspectives on everyday life with obesity: A qualitative study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2018, 13, 1479581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P.H.; Henderson, K.E.; Bell, R.L.; Grilo, C.M. Associations of weight-based teasing history and current eating disorder features and psychological functioning in bariatric surgery patients. Obes. Surg. 2007, 17, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerolini, S.; Vacca, M.; Zegretti, A.; Zagaria, A.; Lombardo, C. Body shaming and internalized weight bias as potential precursors of eating disorders in adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1356647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, K.E.; Warnick, J.; Guthrie, K.M.; Santos, M.; Jelalian, E. Referral to adolescent weight management interventions: Qualitative perspectives from providers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeck, A.; Stelzer, N.; Linster, H.W.; Joos, A.; Hartmann, A. Emotion and eating in binge eating disorder and obesity. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Lessard, L.M. Weight stigma in youth: Prevalence, consequences, and considerations for clinical practice. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, M.L.; Ball, G.D.C.; Bonder, R.; Buchholz, A.; Gorter, J.W.; Morrison, K.M.; Perez, A.; Walker, M.; McPherson, A.C. Exploring the complexities of weight management care for children with spina bifida: A qualitative study with children and parents. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 3440–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.K. Weight centrism in research on children’s active transport to school. J. Transp. Health 2023, 32, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziviani, J.; Macdonald, D.; Ward, H.; Jenkins, D.; Rodger, S. Physical activity and the occupations of children: Perspectives of parents and children. J. Occup. Sci. 2006, 13, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvidas, K.; Burnette, J.L.; Schleider, J.L.; Skelton, J.A.; Moses, M.; Dunsmore, J.C. Healthy body, healthy mind: A mindset intervention for obese youth. J. Genet. Psychol. 2020, 181, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda-Pereda, E.; Echeburúa, E.; Cruz-Sáez, M.S. Anti-fat stereotypes and prejudices among primary school children and teachers in Spain. An. Psicol. 2019, 35, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. Anti-Fat Attitudes in Healthcare. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East London, London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, D. Obesity: Chasing an elusive epidemic. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2013, 43, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, S.J.; Puhl, R.; Cook, S.R.; Slusser, W. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20173034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, S.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Yeazel, M.W.; Hellerstedt, W.L.; Griffin, J.M.; van Ryn, M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Mustafa, M.S.A.; Mahat, I.R.; Shah, M.A.M.M.; Ali, N.A.M.; Mohideen, R.S.; Mahzan, S. The awareness of the impact of body shaming among youth. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, C.; Kraag, G.; Schmidt, J. Body shaming: An exploratory study on its definition and classification. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2023, 5, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiati, T. The influence of body shaming toward FISIP Airlangga University students behaviour pattern. Indones. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Syeda, H.; Shah, I.; Jan, U.; Mumtaz, S. Exploring the impact of body shaming and emotional reactivity on the self-esteem of young adults. CARC Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 2, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.; Wardle, J. Dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: A prospective analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005, 114, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, S.L.; Jones, S.; Davidson, T.L. The outward spiral: A vicious cycle model of obesity and cognitive dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Taylor, C.L.; Wolf, K.; Lawson, R.; Crespo, R. Cultural perceptions of healthy weight in rural Appalachian youth. Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S.; Armstrong, S.C.; Kingsford, E. Adolescent preferences and reactions to language about body weight. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Austin, S.B.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 100, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. The development of self-representations during childhood and adolescence. In Handbook of Self and Identity, 2nd ed.; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 610–642. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, A.P.; Hackell, J.M.; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20172151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Canavarro, M.C. Is body shame a significant mediator of the relationship between mindfulness skills and the quality of life of treatment-seeking children and adolescents with overweight and obesity? Body Image 2016, 20, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, M.; D’Olimpio, F.; Cella, S.; Cotrufo, P. Self-esteem, body shame and eating disorder risk in obese and normal weight adolescents: A mediation model. Eat. Behav. 2016, 21, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, A.A.; Bruening, M. Weight shame, social connection, and depressive symptoms in late adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S. A word to the wise: Adolescent reactions to parental communication about weight. Child Obes. 2018, 14, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, R.L.; Nilsson, K.W.; Leppert, J. Obesity, shame, and depression in school-aged children: A population-based study. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e389–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Xin, X.; Wang, X.; Yao, S. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies in Chinese adolescents with overweight and obesity. Child Obes. 2018, 14, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, M.J.; Canavarro, M.C.; Moreira, H. Is mindful parenting associated with adolescents’ emotional eating? The mediating role of adolescents’ self-compassion and body shame. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society; W. W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M.S.; Mathur, M.A.; Jain, M.S. Body shaming, emotional expressivity, and life orientation among young adults. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2020, 7, 487–493. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR2009362.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Boutelle, K.N.; Kang Sim, D.E.; Rhee, K.E.; Manzano, M.; Strong, D.R. Family-based treatment program contributors to child weight loss. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepczor-Bernat, K. Leczenie choroby otyłościowej u dzieci—Aspekt psychologiczny. In Choroba Otyłościowa u Dzieci i Młodzieży; Wójcik, M., Brzeziński, M., Eds.; Medical Tribune Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, L.H.; Wilfley, D.E.; Kilanowski, C.; Quattrin, T.; Cook, S.R.; Eneli, I.U.; Geller, N.; Lew, D.; Wallendorf, M.; Dore, P.; et al. Family-based behavioral treatment for childhood obesity implemented in pediatric primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Teoria Społecznego Uczenia się; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman-Busato, J.; Schreurs, L.; Halford, J.C.; Yumuk, V.; O’Malley, G.; Woodward, E.; De Cock, D.; Baker, J.L. Providing a common language for obesity: The European Association for the Study of Obesity obesity taxonomy. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, A.; Browne, N.T.; Houser, M.; Blair, G.; Williams, D.R. Weight stigma and bias: A guide for pediatric clinicians. Obes. Pillars 2023, 6, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.N.; Alvarez, E.; Incze, T.; Tarride, J.E.; Kwan, M.; Mbuagbaw, L. Motivational interviewing to promote healthy behaviors for obesity prevention in young adults (MOTIVATE): A pilot randomized controlled trial protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.T.; Amankwah, E.K.; Hernandez, R.G. Assessment of weight bias among pediatric nurses and clinical support staff toward obese patients and their caregivers. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, e244–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.J.; Finch, L.E.; Belsky, A.C.I.; Buss, J.; Finley, C.; Schwartz, M.B.; Daubenmier, J. Weight bias in 2001 versus 2013: Contradictory attitudes among obesity researchers and health professionals. Obesity 2015, 23, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberga, A.S.; Edache, I.Y.; Forhan, M.; Russell-Mayhew, S. Weight bias and health care utilization: Scoping review. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachyra, P.; Anagnostou, E.; Knibbe, T.J.; Petta, C.; Cosgrove, S.; Chen, L.; Capano, L.; Moltisanti, L.; McPherson, A.C. Weighty conversations: Caregivers’, children’s, and clinicians’ perspectives and experiences of discussing weight-related topics in healthcare consultations. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maïano, C.; Aimé, A.; Lepage, G.; ASPQ Team; Morin, A.J.S. Psychometric properties of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) among a sample of overweight/obese French-speaking adolescents. Eat. Weight Disord. 2019, 24, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, S.F.; Price, S.L.; Penney, T.L.; Rehman, L.; Lyons, R.F.; Piccinini-Vallis, H.; Vallis, T.M.; Curran, J.; Aston, M. Blame, shame, and lack of support: A multilevel study on obesity management. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, R.; Oliver, K.; Woodman, J.; Thomas, J. The views of young children in the UK about obesity, body size, shape and weight: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Mikulska, M.; Matusik, P. Analysis of Blame, Guilt, and Shame Related to Body and Body Weight and Their Relationship with the Context of Psychological Functioning Among the Pediatric Population with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111763

Czepczor-Bernat K, Mikulska M, Matusik P. Analysis of Blame, Guilt, and Shame Related to Body and Body Weight and Their Relationship with the Context of Psychological Functioning Among the Pediatric Population with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111763

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzepczor-Bernat, Kamila, Marcela Mikulska, and Paweł Matusik. 2025. "Analysis of Blame, Guilt, and Shame Related to Body and Body Weight and Their Relationship with the Context of Psychological Functioning Among the Pediatric Population with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111763

APA StyleCzepczor-Bernat, K., Mikulska, M., & Matusik, P. (2025). Analysis of Blame, Guilt, and Shame Related to Body and Body Weight and Their Relationship with the Context of Psychological Functioning Among the Pediatric Population with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 17(11), 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111763