Prevalence of and Contributors to Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

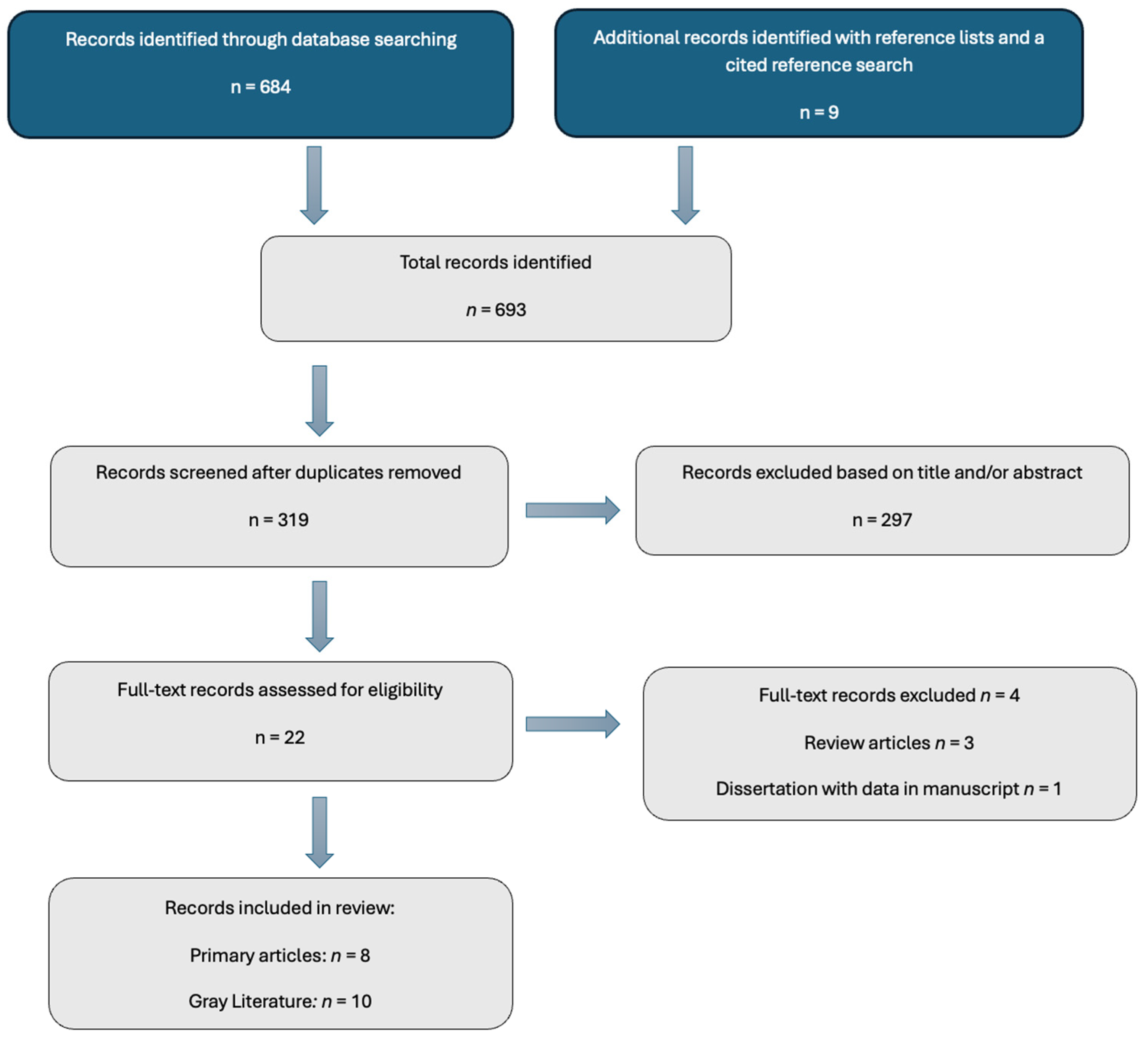

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Institution Types

3.3. Participant Demographics

3.4. Assessment Tools for FI

3.5. Prevalence

3.6. Contributors

4. Discussion

4.1. Financial Challenges

4.2. Meal Plans

4.3. Time

4.4. Housing

4.5. COVID-19

4.6. Impact of FI among Student-Athletes

4.7. NCAA Feeding Regulations

4.8. Intervention Strategies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rabbitt, M.P.; Hales, L.J.; Burke, M.P.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2022; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Adamovic, E.; Newton, P.; House, V. Food Insecurity on a College Campus: Prevalence, Determinants, and Solutions. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruening, M.; Brennhofer, S.; van Woerden, I.; Todd, M.; Laska, M. Factors Related to the High Rates of Food Insecurity among Diverse, Urban College Freshmen. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, C.C.; Camel, S.P.; Mayeux, W. Food Insecurity among Female Collegiate Athletes Exists despite University Assistance. J. Am. Coll. Health J. ACH 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larin, K. Food Insecurity: Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits; US Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Loofbourrow, B.M.; Scherr, R.E. Food Insecurity in Higher Education: A Contemporary Review of Impacts and Explorations of Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reader, J.; Gordon, B.; Christensen, N. Food Insecurity among a Cohort of Division I Student-Athletes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.L.; Karpinski, C.; Bragdon, M.; Mackenzie, M.; Abbey, E. Prevalence of Food Insecurity in NCAA Division III Collegiate Athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health J. ACH 2023, 71, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimera, L.; Dellana, J.; Farris, A.; Wentz, L.; Harman, T.; Dommel, A.; Rushing, K.; Stowers, L.; Behrens, C., Jr. Food Insecurity Among College Student Athletes in the Southeastern Region: A Multi-Site Study. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2023, 16, 272. [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick-Rab, S.; Richardson, B.; Baker-Smith, C. Hungry to Win: A First Look at Food and Housing Insecurity among Student-Athletes; 2020. Available online: https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/hungry-to-win.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Anziano, J.; Zigmont, V.A. Understanding Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Qualitative Study at a Public University in New England. J. Athl. Train. 2024, 59, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauman, K.; Achen, R.; Barnes, J.L. The Five Most Significant Barriers to Healthy Eating in Collegiate Student-Athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health J. ACH 2023, 71, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, A.; Shields, D.; Henning, M. Perceived Hunger in College Students Related to Academic and Athletic Performance. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, T. Food Insecurity in Collegiate Student-Athletes. Train. Cond. 2022. Available online: https://training-conditioning.com/article/food-insecurity-in-collegiate-student-athletes/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: 2020; ISBN 978-0-648-84880-6. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Daniels, E.; Hanson, J. Energy-Adjusted Dietary Intakes Are Associated with Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating but Not Food Insecurity or Sports Nutrition Knowledge in a Pilot Study of ROTC Cadets. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poll, K.L.; Holben, D.H.; Valliant, M.; Joung, H.-W.D. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Disordered Eating Behaviors in NCAA Division 1 Male Collegiate Athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health J ACH 2020, 68, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellana, J.; Chimera, L.; Farris, A.; Nunnery, D.; Harman, T.; Dommel, A.; Rushing, K.; Stowers, L.; C Behrens, J. The Impact of Sexual Orientation on Food Insecurity Among Division 1 Student Athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2023, 16, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, W.; Tingom, J.; Tredinnick, V.; Pfeiffer, S.; A Knab, F. Effect of Quarantine and Isolation on Nutrition and Food Insecurity in Student-Athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2022, 16, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux, W.; Camel, S.; Douglas, C. Prevalence of Food Insecurity in Collegiate Athletes Warrants Unique Solutions. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa043_090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poll, K.; Valliant, M.; Joung, H.-W.D.; Holben, D.H. Food Insecurity and Food Behaviors of Male Collegiate Athletes. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 791.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anziano, J. Food Insecurity among College Athletes at a Public University in New England. Master’s Thesis, Southern Connecticut State University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, T. Improving Health Programs for Seton Hill University First-Generation College Student-Athletes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Misener, P. Food Insecurity and College Athletes: A Study on Food Insecurity/Hunger among Division III Athletes. Ph.D. Thesis, State University, Binghamton, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, K. Food Insecurity, Academic and Athletic Performance of Collegiate Athletes Survey Research Paper. Master’s Thesis, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stowers, L.; Harman, T.; Pavela, G.; Fernandez, J.R. The Impact of Food Security Status on Body Composition Changes in Collegiate Football Players. Int. J. Sports Exerc. Med. 2022, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA ERS-Survey Tools. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/survey-tools/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Martinez, S.M.; Webb, K.; Frongillo, E.A.; Ritchie, L.D. Food Insecurity in California’s Public University System: What Are the Risk Factors? J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNAP Eligibility|Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Dubick, J.; Mathews, B.; Cady, C. Hunger on Campus: The Challenge of Food Insecurity for College Students. 2016. Available online: https://studentsagainsthunger.org/hunger-on-campus/ (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- The Annie, E.; Casey Foundation. Exploring America’s Food Deserts. Available online: https://www.aecf.org/blog/exploring-americas-food-deserts (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Hagedorn, R.L.; Walker, A.E.; Wattick, R.A.; Olfert, M.D. Newly Food-Insecure College Students in Appalachia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Poverty and Food Insecurity May Increase as the Threat of COVID-19 Spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3236–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitt, E.D.; Heer, M.M.; Winham, D.M.; Knoblauch, S.T.; Shelley, M.C. Effects of COVID-19 on University Student Food Security. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eck, K.M.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Food Choice Decisions of Collegiate Division I Athletes: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Our Division II Students. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/4/21/our-division-ii-students.aspx (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Our Division III Students. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/5/11/our-division-iii-students.aspx (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Our Division I Students. Available online: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/5/11/our-division-i-students.aspx (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- NCAA LSDBi Bylaw 16.5.1. Available online: https://web3.ncaa.org/lsdbi/search/bylawView?id=12180 (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Running an On-Campus Food Pantry. The Student PIRGs. Available online: https://studentpirgs.org/assets/uploads/2019/03/NSCAHH_Food_Pantry_Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2024).

| Citation | Type of Institution | Participant Demographics | Tool to Assess FI | Prevalence of FI | Contributors to FI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-Reviewed Articles | |||||

| Anziano & Zigmont, 2023 [11] | Public university in New England | -NCAA athletes (division not noted) -N = 10 -Food insecure -White: 90% -Females: 50% -On campus: 80.0% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 100%: only surveyed those with FI | -Lack of time -Special dietary needs -Limited campus dining options -Lack of healthy options in dining hall -Limited kitchen access -Limited access to transportation |

| Brown et al., 2023 [8] | -Multiple institutions -Unspecified location and type | -NCAA DIII -N = 787 -Female: 63.3% -White: 81.5% -First generation: 19% -Pell recipient: 18.2% -Live on campus: 81% -Have a meal plan: 83.3% Family Income: -<$25,000: 5.4% -$25,000–49,999: 6.5% -$50,000–74,999: 16.5% -$75,000–99,999: 12.9% -$100,000+: 39.8% | 5 questions from 6-item US-HFSSM and 17 researcher-created questions | Overall: 14.7% By ethnicity: -White: 13.3% -Hispanic: 18.3% -Black: 31% -Asian: 8.5% -NHPI: 100% By meal plan: -With: 11.5% -Without: 29.9% By Pell Grant: -Yes: 26.5% -No: 11.1% First Generation: -Yes: 27.2% -No: 11.3% FI before college: -Yes: 52.5% -No: 11.5% | -Games during dining hours -Living off campus and/or limited money -Practice during dining hours -Regulation and restriction of feeding in DIII |

| Daniels & Hanson, 2021 [16] | Public land-grant research university in Kansas | -Army ROTC cadets -N = 37 -Female: 30% -White: 86.5% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 27% | -Social -Access -Personal |

| Douglas et al., 2022 [4] | Public university in rural East Texas | -NCAA DI -N = 78 -Female -White: 75.6% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 32% | -Timing of practice -Limited dining hall hours -Lack of financial resources -Lack of cooking skills and equipment |

| Goldrick-Rab et al., 2020 [10] | 171 2-year and 56 4-year institutions across the U.S. | -13 NCAA DI -11 NCAA DII -24 NCAA DIII -124 2-Year Colleges -N = 3506 | 18-item US-HFSSM | -DI: 24% -DII: 26% -DIII: 21% -2-Year institutions: 39% | Limited financial resources |

| Hickey et al., 2019 [13] | Public liberal arts university in New Hampshire | -NCAA DIII -N = 371 (not all athletes) -Female: 65.8% -Athletes: 78.17% -White: 89.8% -Have a meal plan: 80.8% -First generation: 24.9% | Survey developed specifically for the study | 34.6% | None reported |

| Poll et al., 2020 [17] | Public research university in Mississippi | -NCAA DI -N = 111 -Male | Childhood History of Food Insecurity Questionnaire | 9.9% | FI before college |

| Reader et al., 2022 [7] | State University in Northwest U.S. | -NCAA DI -N = 45 -Female: 73.33% -White: 68.89% -On campus: 44.4% | 10-item US-HFSSM | 60% | -Balancing academics and athletics -Elevated energy needs -COVID-19 -Living location -Lack of financial resources |

| Abstracts | |||||

| Chimera et al., 2022 [9] | Public university in rural North Carolina and public research university in urban Alabama | -NCAA DI -None reported | 10-item US-HFSSM | 50% | Greater in urban vs. rural |

| Dellana et al., 2023 [18] | Public university in rural North Carolina and public research university in urban Alabama | -NCAA DI -N = 404 -LGBTQ+: N = 24 | 10-item US-HFSSM | 45.6% | None reported |

| Gagnon et al., 2023 [19] | Not reported | -N = 124 -Female: 55% -White: 66% | Researcher developed survey | 65% | -Financial insecurity -Dining hall hours -COVID isolation |

| Mayeux et al., 2020 [20] | Public university in rural East Texas | -NCAA (no division noted) -N = 91 -Female: 85.7% -White: 67% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 39.6% | -Lack of financial resources -Lack of time |

| Poll et al., 2017 [21] | University in southeast | -NCAA DI -N = 93 -Male -White: 48.4% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 16% | None reported |

| Theses/Dissertations | |||||

| Anziano, 2020 [22] | Public university in Connecticut | -NCAA DII -N = 18 -White: 88.9% -Live on campus: 83.3% -Female: 50% Hours worked per week: -0: 66.7% -1–12: 22.2% -12+: 11.1% Financing college: -Self-pay: 27.8% -Scholarships/grants: 55.6% -Loans: 38.9% -Assistance from others: 50% Meal plan: -None: 5.6% -Unlimited: 61.1% -Declining balance: 33.3% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 44.4% | -Lack of time -Family history -Spending priorities -Transportation -Limitations of dining halls -Meal plan -Limited kitchen access -Lack of assistance from coaches/universities |

| Bowman, 2020 [23] | Private Catholic university in Pennsylvania | -NCAA DII -N = 31 -First generation -Male: 71% -White: 55% | 10-item US-HFSSM | 40% | -Older students -Male -Female |

| Misener, 2020 [24] | Private liberal arts college in northeast | -NCAA DIII -N = 424 -Female: 46.5% -White: 79% | 6-item US-HFSSM | 31.8% in season | -Greater in male vs. female -Greater in white vs. non-white -Based on sport -Ran out of money for swipes -Ran out of money for campus food court -Unable to afford balanced meals -Correlated with receiving grant money -Correlated with being first-generation |

| Nilsson, 2023 [25] | University in southwest | -NCAA (division not noted -N = 70 -Female: 56.25% -Living location:-Campus housing: 28.13% -Off-campus, walking distance: 26.56% -Off-campus, driving distance: 45.31% | 10-item US-HFSSM | Not reported | -Dining hall hours conflict with practice/game times -Living location -Limited resources (money) |

| Stowers et al., 2022 [26] | University in southeast | -NCAA DI -Football players -N = 85 -Male | 10-item US-HFSSM | 63% | Greater in black vs. white |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacenta, J.; Starkoff, B.E.; Lenz, E.K.; Shearer, A. Prevalence of and Contributors to Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091346

Pacenta J, Starkoff BE, Lenz EK, Shearer A. Prevalence of and Contributors to Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(9):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091346

Chicago/Turabian StylePacenta, Jamie, Brooke E. Starkoff, Elizabeth K. Lenz, and Amanda Shearer. 2024. "Prevalence of and Contributors to Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 16, no. 9: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091346

APA StylePacenta, J., Starkoff, B. E., Lenz, E. K., & Shearer, A. (2024). Prevalence of and Contributors to Food Insecurity among College Athletes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 16(9), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091346