Pharmacological Studies in Eating Disorders: A Historical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

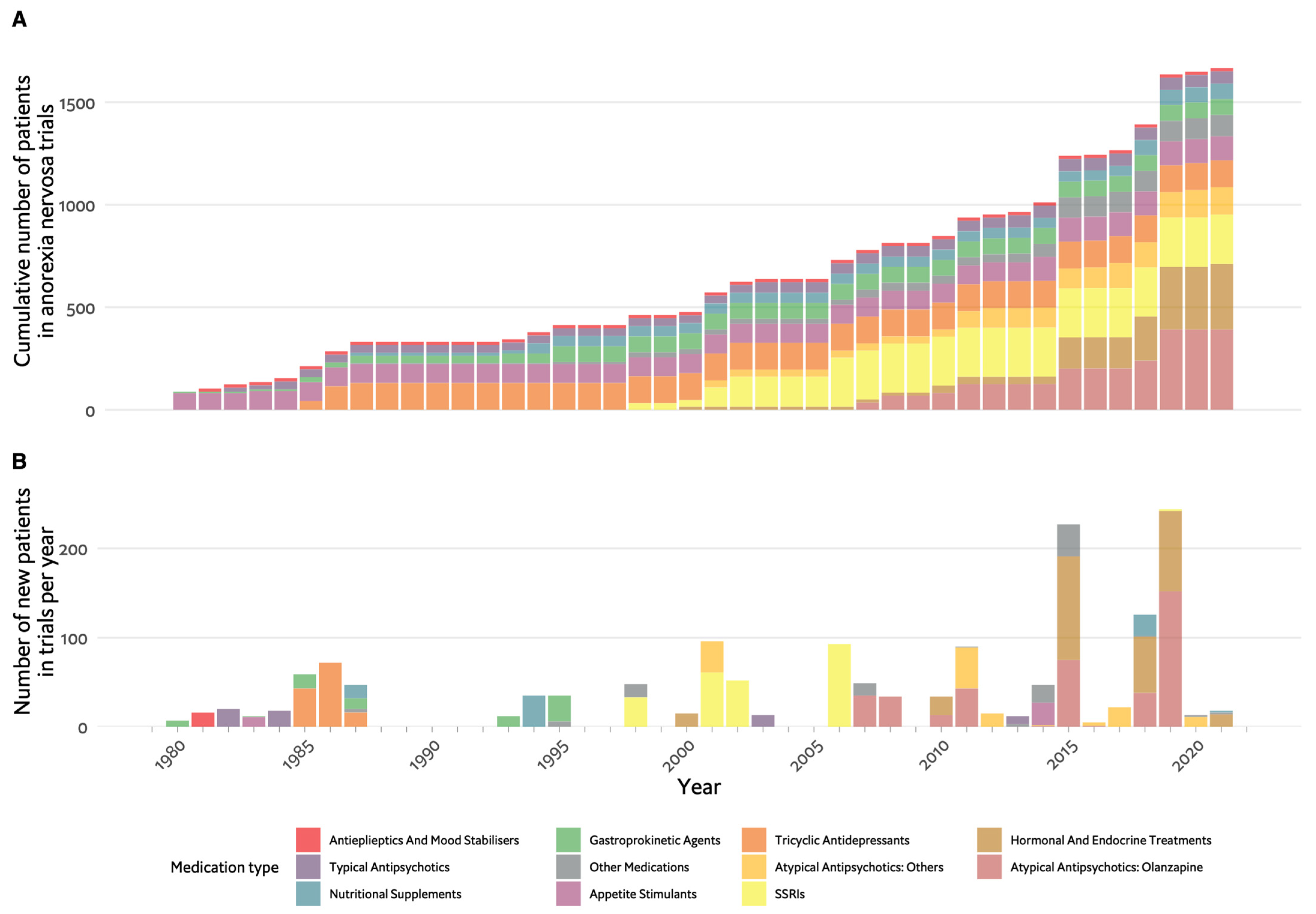

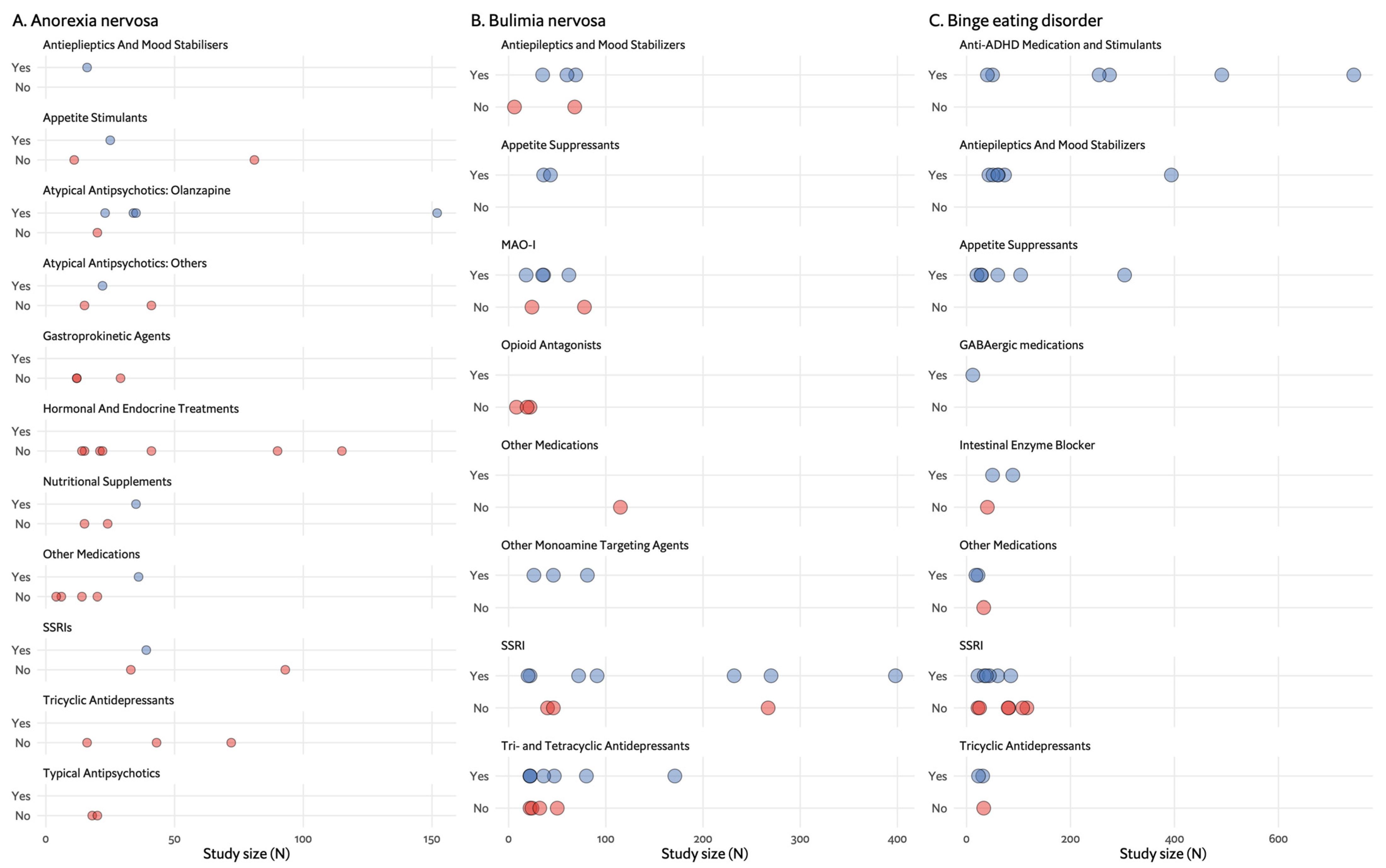

2. Restrictive Eating Disorders and Anorexia Nervosa

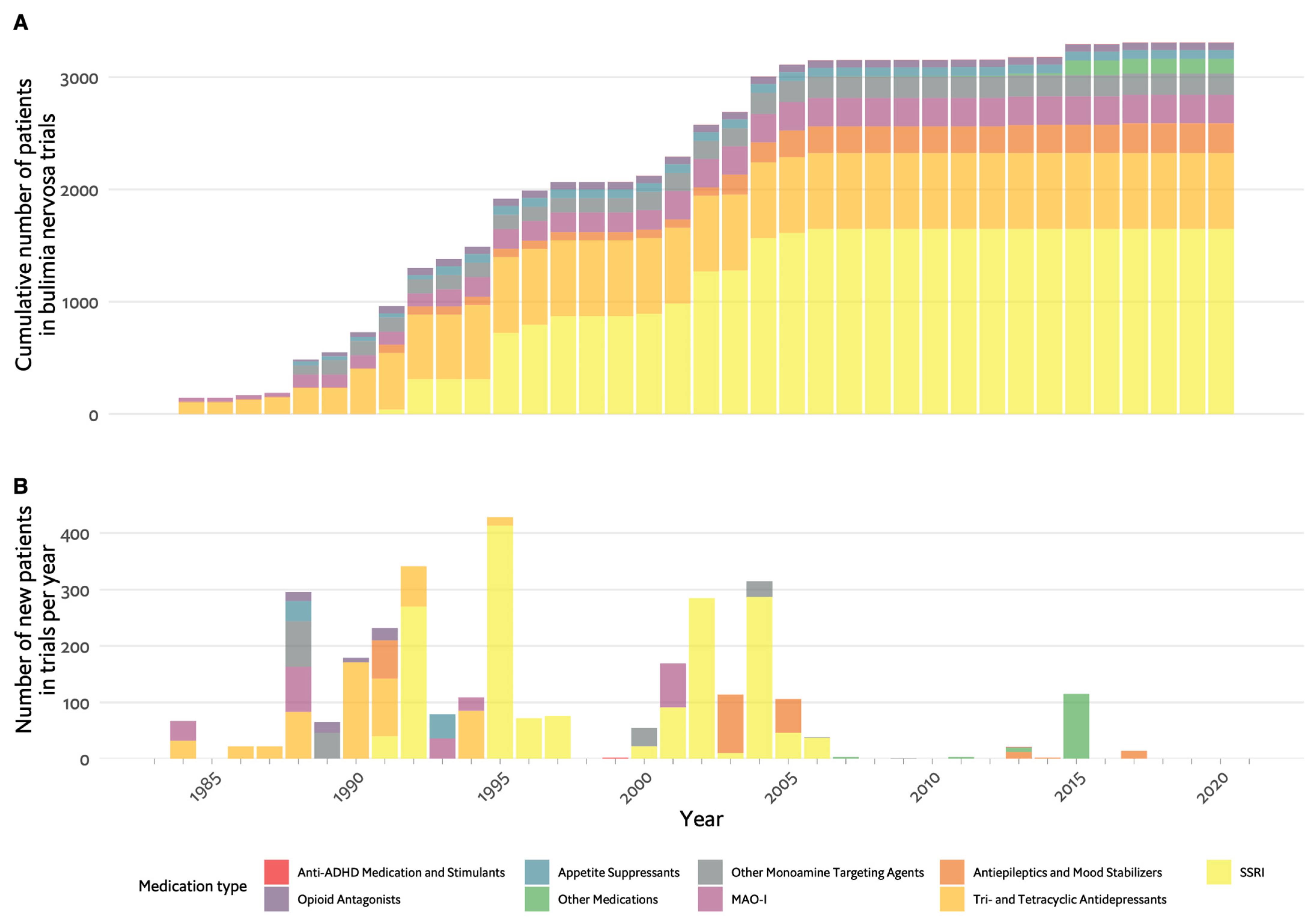

3. Bulimia Nervosa

4. Binge Eating Disorder

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780890425541. [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000–2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, J.; Duarte, T.A.; Schmidt, U. Eating Disorders. Lancet 2020, 395, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suokas, J.T.; Suvisaari, J.M.; Gissler, M.; Löfman, R.; Linna, M.S.; Raevuori, A.; Haukka, J. Mortality in Eating Disorders: A Follow-up Study of Adult Eating Disorder Patients Treated in Tertiary Care, 1995–2010. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerwas, S.; Larsen, J.T.; Petersen, L.; Thornton, L.M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Bulik, C.M. The Incidence of Eating Disorders in a Danish Register Study: Associations with Suicide Risk and Mortality. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 65, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerich, H.; Hotopf, M.; Shetty, H.; Schmidt, U.; Treasure, J.; Hayes, R.D.; Stewart, R.; Chang, C.K. Psychiatric Comorbidity as a Risk Factor for Mortality in People with Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology, Course, and Outcome of Eating Disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2013, 26, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, U.; Adan, R.; Böhm, I.; Campbell, I.C.; Dingemans, A.; Ehrlich, S.; Elzakkers, I.; Favaro, A.; Giel, K.; Harrison, A.; et al. Eating Disorders: The Big Issue. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment; NICE: London, UK, 2020; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, A.; Hoek, H.W.; Schmidt, R. Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Eating Disorders: International Comparison. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, K.T.; Tabri, N.; Thomas, J.J.; Murray, H.B.; Keshaviah, A.; Hastings, E.; Edkins, K.; Krishna, M.; Herzog, D.B.; Keel, P.K.; et al. Recovery from Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa at 22-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmerich, H.; Treasure, J. Psychopharmacological Advances in Eating Disorders. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmerich, H.; Lewis, Y.D.; Conti, C.; Mutwalli, H.; Karwautz, A.; Sjögren, J.M.; Uribe Isaza, M.M.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M.; Aigner, M.; McElroy, S.L.; et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines Update 2023 on the Pharmacological Treatment of Eating Disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 643–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, M.; Treasure, J.; Kaye, W.; Kasper, S. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Eating Disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 12, 400–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M.M. Die Entwicklung der Psychopharmakologie im Zeitalter der Naturwiusenschaftlichen Medizin; Urban & Vogel: München, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bergner, L.; Himmerich, H.; Steinberg, H. Die Therapie der Nahrungsverweigerung und der Anorexia Nervosa in deutschsprachigen Psychiatrie-Lehrbüchern der vergangenen 200 Jahre. Fortschritte Neurol. Psychiatr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H. Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie; Erlangen: Stuttgart, Germany, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Heinroth, J.C.A. Lehrbuch der Störungen des Seelenlebens oder der Seelenstörungen und ihrer Behandlung; Vogel: Leipzig, Germany, 1818. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzielski, A.; Kaźmierczak, N.; Grzybowski, A. Sir William Withey Gull (1816–1890). J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, W.W. Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica). Trans. Clin. Soc. Lond. 1874, 7, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostroem, A. Kurzgefasstes Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie von Johannes Lange, 4th ed.; Thieme: Leipzig, Germany, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Bangen, H.C. Geschichte der Medikamentösen Therapie der Schizophrenie; Verlag f. Wiss. U. Bildung: Berlin, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Linde, O.K. Pharmakopsychiatrie im Wandel der Zeit; Tilia: Klingenmünster, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, J. Kurzgefasstes Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie; Thieme: Leipzig, Germany, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, A.E. From Shock Therapy to Psychotherapy: The Role of Peter Dally in the Revolutions of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2010, 18, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dally, P.J.; Sargant, W. Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Br. Med. J. 1960, 1, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Braslow, J.T.; Marder, S.R. History of Psychopharmacology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 15, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, G. From Shock Therapy to Psychotherapy: The Role of Peter Dally in the Revolutions of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment. Commentary. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2010, 18, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of 21 Antidepressant Drugs for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Samara, M.; Peter, N.; Arndt, T.; Bäckers, L.; Rothe, P.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Multi-Episode Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, E.; Steinglass, J.E.; Timothy Walsh, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, P.; Schreyer, C.; Wildes, J.; Yilmaz, Z.; Guarda, A.S.; Kaplan, A.S.; et al. Olanzapine versus Placebo in Adult Outpatients with Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandereycken, W. Neuroleptics in the Short-Term Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study with Sulpiride. Br. J. Psychiatry 1984, 144, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandereycken, W.; Pierloot, R. Pimozide Combined with Behavior Therapy in the Short Term Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa—A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-over Study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1982, 66, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassano, G.B.; Miniati, M.; Pini, S.; Rotondo, A.; Banti, S.; Borri, C.; Camilleri, V.; Mauri, M. Six Month Open Trial of Haloperidol as an Adjunctive Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa A Preliminary Report. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 33, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, M.; Miniati, M.; Mariani, M.G.; Ciberti, A.; Dell’Osso, L. Haloperidol for Severe Anorexia Nervosa Restricting Type with Delusional Body Image Disturbance: A Nine-Case Chart Review. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2013, 18, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, P.S.; Klabunde, M.; Kaye, W. Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Quetiapine in Anorexia Nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, J.; Gralla, J.; Sigel, E.; Ellert, S.; Dodge, M.; Gardner, R.; O’Lonergan, T.; Frank, G.; Wamboldt, M.Z. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Risperidone for the Treatment of Adolescents and Young Adults with Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, G.M.; Laini, V.; Mauri, M.C.; Ferrari, V.M.S.; Clemente, A.; Lugo, F.; Mantero, M.; Redaelli, G.; Zappulli, D.; Cavagnini, F. A Single Blind Comparison of Amisulpride, Fluoxetine and Clomipramine in the Treatment of Restricting Anorectics. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 25, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W. Aripiprazole, a Partial Dopamine Agonist to Improve Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa A Case Series. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunko, M.E.; Schwartz, T.A.; Duvvuri, V.; Kaye, W.H. Aripiprazole in Anorexia Nervosa and Low Weight Bulimia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 44, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahıllıoğlu, A.; Özcan, T.; Yüksel, G.; Majroh, N.; Köse, S.; Özbaran, B. Is Aripiprazole a Key to Unlock Anorexia Nervosa?: A Case Series. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W.; Shott, M.E.; Hagman, J.O.; Schiel, M.A.; DeGuzman, M.C.; Rossi, B. The Partial Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonist Aripiprazole Is Associated with Weight Gain in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spettigue, W.; Buchholz, A.; Henderson, K.; Feder, S.; Moher, D.; Kourad, K.; Gaboury, I.; Norris, M.; Ledoux, S. Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Olanzapine as an Adjunctive Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescent Females: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. BMC Pediatr. 2008, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissada, H.; Tasca, G.A.; Barber, A.M.; Bradwejn, J. Olanzapine in the Treatment of Low Body Weight and Obsessive Thinking in Women with Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, F.; Amianto, F.; Dalle Grave, R.; Fassino, S. Lack of Efficacy of Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments of Disorders of Eating Behavior: Neurobiological Background. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, E.; Kaplan, A.S.; Walsh, B.T.; Gershkovich; Yilmaz, Z.; Musante, D.; Wang, Y. Olanzapine versus Placebo for Out-Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafantaris, V.; Leigh, E.; Hertz, S.; Berest, A.; Schebendach, J.; Sterling, W.M.; Saito, E.; Sunday, S.; Higdon, C.; Golden, N.H.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Adjunctive Olanzapine for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spettigue, W.; Norris, M.L.; Santos, A.; Obeid, N. Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: A Case Series Examining the Feasibility of Family Therapy and Adjunctive Treatments. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggero, C.; Masi, G.; Brunori, E.; Calderoni, S.; Carissimo, R.; Maestro, S.; Muratori, F. Low-Dose Olanzapine Monotherapy in Girls with Anorexia Nervosa, Restricting Subtype: Focus on Hyperactivity. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 20, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacher, G.; Abatzi-Wenzel, T.A.; Wiesnagrotzki, S.; Bergmann, H.; Schneider, C.; Gaupmann, G. Gastric Emptying, Body Weight and Symptoms in Primary Anorexia Nervosa. Long-Term Effects of Cisapride. Br. J. Psychiatry 1993, 162, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.M.; Freedman, M.L.; Feiglin, D.H.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N.; Swinson, R.P.; Garfinkel, P.E. Delayed Gastric Emptying and Improvement with Domperidone in a Patient with Anorexia Nerovsa. Am. J. Psychiatry 1983, 140, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, J.W.; Lebwohl, P. Metoclopramide-induced Gastric Emptying in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1980, 74, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andries, A.; Frystyk, J.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Støving, R.K. Dronabinol in Severe, Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Herzog, D.B.; Rivinus, T.M.; Harper, G.P.; Ferber, R.A.; Rozenbaum, J.F.; Harmatz, J.S.; Tondorf, R.; Orsulak, P.J.; Schildkraut, J.J. Amitriptyline in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1985, 5, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmi, K.A.; Eckert, E.; Ladu, T.J.; Cohen, J. Anorexia Nervosa: Treatment Efficay of Cyproheptadine and Amitriptyline. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1986, 43, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starcevic, V.; Janca, A. Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders: Still in Search of the Concept-Affirming Boundaries. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassino, S.; Leombruni, P.; Daga, G.A.; Brustolin, A.; Migliaretti, G.; Cavallo, F.; Rovera, G.G. Efficacy of Citalopram in Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 12, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, W.H.; Nagata, T.; Weltzin, T.E.; Hsu, L.K.G.; Sokol, M.S.; McConaha, C.; Plotnicov, K.H.; Weise, J.; Deep, D. Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Administration of Fluoxetine in Restricting- and Restricting-Purging-Type Anorexia Nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.T.; Kaplan, A.S.; Attia, E.; Parides, M.; Carter, J.C.; Pike, K.M.; Devlin, M.J.; Woodside, B.; Roberto, C.A. Fluoxetine After Weight Restoration in Anorexia Nervosa. JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.; Haiman, C.; Timothy Walsh, B.; Flater, S.R. Does Fluoxetine Augment the Inpatient Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa? Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B.; Lewis, Y.D.; Bartholdy, S.; Kekic, M.; Mcclelland, J.; Campbell, I.C.; Schmidt, U. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Treatment in Severe, Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: An Open Longer-Term Follow-Up. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Touyz, S.; Sud, R. Treatment for Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: A Review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolnick, B.; Zupec-Kania, B.; Calabrese, L.; Aoki, C.; Hildebrandt, T. Remission from Chronic Anorexia Nervosa with Ketogenic Diet and Ketamine: Case Report. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, T.; Trunko, M.E.; Feifel, D.; Lopez, E.; Peterson, D.; Frank, G.K.W.; Kaye, W. A Longitudinal Case Series of IM Ketamine for Patients with Severe and Enduring Eating Disorders and Comorbid Treatment-Resistant Depression. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e03869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Maguire, S.; Hunt, G.E.; Kesby, A.; Suraev, A.; Stuart, J.; Booth, J.; McGregor, I.S. Intranasal Oxytocin in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa: Randomized Controlled Trial during Re-Feeding. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 87, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, P.K.; Lawson, E.A.; Faje, A.T.; Eddy, K.T.; Lee, H.; Fiedorek, F.T.; Breggia, A.; Gaal, I.M.; DeSanti, R.; Kilbanski, A. Treatment with a Ghrelin Agonist in Outpatient Women with Anorrexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clinial Psychiatry 2018, 79, 7823. [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli, P.K.; Lawson, E.A.; Prabhakaran, R.; Miller, K.K.; Donoho, D.A.; Clemmons, D.R.; Herzog, D.B.; Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Effects of Recombinant Human Growth Hormone in Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 4889–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antel, J.; Tan, S.; Grabler, M.; Ludwig, C.; Lohkemper, D.; Brandenburg, T.; Barth, N.; Hinney, A.; Libuda, L.; Remy, M.; et al. Rapid Amelioration of Anorexia Nervosa in a Male Adolescent during Metreleptin Treatment Including Recovery from Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milos, G.; Antel, J.; Kaufmann, L.K.; Barth, N.; Koller, A.; Tan, S.; Wiesing, U.; Hinney, A.; Libuda, L.; Wabitsch, M.; et al. Short-Term Metreleptin Treatment of Patients with Anorexia Nervosa: Rapid on-Set of Beneficial Cognitive, Emotional, and Behavioral Effects. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl-Dietsch, G.; Milos, G.; Wabitsch, M.; Bell, R.; Tschöpe, F.; Antel, J.; Hebebrand, J. Rapid Emergence of Appetite and Hunger Resulting in Weight Gain and Improvement of Eating Disorder Symptomatology during and after Short-Term Off-Label Metreleptin Treatment of a Patient with Anorexia Nervosa. Obes. Facts 2023, 16, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G. Bulimia Nervosa: An Ominous Variant of Anorexia Nervosa. Psychol. Med. 1979, 9, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R. Bulimia Nervosa: 25 Years On. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 447–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R. The Treatment of Depressive States with G 22355 (Imipramine Hydrochloride). Am. J. Psychiatry 1958, 115, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agras, W.S.; Dorian, B.; Kirkley, B.G.; Arnow, B.; Bachman, J. Imipramine in the Treatment of Bulimia: A Double-blind Controlled Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Blouin, J.; Blouin, A.; Perez, E. Treatment of Bulimia with Desipramine: A Double-Blind Crossover Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 1988, 33, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, P.L.; Wells, L.A.; Cunningham, C.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Treating Bulimia with Desipramine. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1986, 43, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, G.; Hudson, I.; Jonas, M. Bulimia Treated with Imipramine: A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 1983, 140, 554–558. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine, E.; Yonace, A.; Farrington, A.; Barratt, K.; Wakeling, A. Bulimia Nervosa: A Placebo Controlled Double-blind Therapeutic Trial of Mianserin. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1983, 15, 195S–202S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, B.T.; Gladis, M.; Roose, S.P.; Stewart, J.W.; Stetner, F.; Glassman, A.H. Phenelzine vs Placebo in 50 Patients with Bulimia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988, 45, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.T.; Stewart, J.W.; Roose, S.P.; Gladis, M.; Glassman, A.H. Treatment of Bulimia with Phenelzine: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1984, 41, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruba, M.O.; Cuzzolaro, M.; Riva, L.; Bosello, O.; Liberti, S.; Castra, R.; Dalle Grave, R.; Santonastaso, P.; Garosi, V.; Nisoli, E. Efficacy and Tolerability of Moclobemide in Bulimia Nervosa: A Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Ralevski, E.; Davis, C.; Davis, C.; D’Souza, J.D. Is There a Role for Selective Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor Therapy in Bulimia Nervosa? A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Brofaromine. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993, 13, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Piran, N.; Warsh, J.J.; Prendergast, P.; Mainprize, E.; Whynot, C.; Garfinkel, P.E. A Trial of Isocarboxazid in the Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1988, 8, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, R.; Quitkin, H.M.; Quitkin, F.M.; Stewart, J.W.; Mcgrath, P.J.; Tricamo, E. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Comparison of Phenelzine and Lmipramine in the Treatment of Bulimia in Atypical Depressives. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, S.J. Pharmacologic Treatment of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.T.; Perry, K.W.; Bymaster, F.P. The Discovery of Fluoxetine Hydrochloride (Prozac). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogowicz, P.; Curtis, H.J.; Walker, A.J.; Cowen, P.; Geddes, J.; Goldacre, B. Trends and Variation in Antidepressant Prescribing in English Primary Care: A Retrospective Longitudinal Study. BJGP Open 2021, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brody, D.J.; Gu, Q. Antidepressant Use among Adults: United States, 2015–2018; NCHS Data Brief; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bacaltchuk, J.; Hay, P.P. Antidepressants versus Placebo for People with Bulimia Nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group. Fluoxetine in the Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa: A Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1992, 49, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.T.; Agras, W.S.; Devlin, M.J.; Fairburn, C.G.; Wilson, G.T.; Khan, C.; Chally, M.K. Fluoxetine for Bulimia Nervosa Following Poor Response to Psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.J.; Wilson, M.G.; Thompson, V.L.; Potvin, J.H. Long-Term Fluoxetine Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa. Br. J. Psychiatry 1995, 166, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, S.J.; Halmi, K.A.; Sarkar, N.P.; Koke, S.C.; Lee, J.S. A Placebo-Controlled Study of Fluoxetine in Continued Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa after Successful Acute Fluoxetine Treatment. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichter, M.M.; Leibl, K.; Rief, W.; Brunner, E.; Schmidt-Auberger, S.; Engel, R.R. Fluoxetin versus Placebo: A Double-Blind Study with Bulimic Inpatients Undergoing Intensive Psychotherapy. Pharmacopsychiatry 1991, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, N.Y.; AlRabiah, H.K.; AL Rasoud, S.S.; Bari, A.; Wani, T.A. Topiramate: Comprehensive Profile. Profiles DrugSubst. Excip. Relat. Methodol. 2019, 44, 333–378. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, D.W.; Reimherr, F.W.; Hoopes, S.P.; Rosenthal, N.R.; Kamin, M.; Karim, R.; Capece, J.A. Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa With Topiramate in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial, Part 2: Improvement in Psychiatric Measures. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, C.; Tritt, K.; Muehlbacher, M.; Gil, F.P.; Mitterlehner, F.O.; Kaplan, P.; Lahmann, C.; Leiberich, P.K.; Krawczyk, J.; Kettler, C.; et al. Topiramate Treatment in Bulimia Nervosa Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 38, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopes, S.P.; Reimherr, F.W.; Hedges, D.W.; Rosenthal, N.R.; Kamin, M.; Karim, R.; Capece, J.A.; Karvois, D. Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa with Topiramate in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial, Part 1: Improvement in Binge and Purge Measures. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentari, E.; Hughes, A.; Feeney, J.; Stone, M.; Rochester, G.; Levenson, M.; Ware, J. Statistical Review and Evaluation. Antiepileptic Drugs and Suicidality; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leombruni, P.; Amianto, F.; Delsedime, N.; Gramaglia, C.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Fassino, S. Citalopram versus Fluoxetine for the Treatment of Patients with Bulimia Nervosa: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv. Ther. 2006, 23, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, M.E.; Friedman, A. A Systematic Review of Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-E) for Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 53, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunko, M.E.; Schwartz, T.A.; Berner, L.A.; Cusack, A.; Nakamura, T.; Bailer, U.F.; Chen, J.Y.; Kaye, W.H. A Pilot Open Series of Lamotrigine in DBT-Treated Eating Disorders Characterized by Significant Affective Dysregulation and Poor Impulse Control. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2017, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerdjikova, A.I.; Blom, T.J.; Martens, B.E.; Keck, P.E.; McElroy, S.L. Zonisamide in the Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa: An Open-Label, Pilot, Prospective Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Eom, J.S.; Yang, J.W.; Kang, J.; Treasure, J. The Impact of Oxytocin on Food Intake and Emotion Recognition in Patients with Eating Disorders: A Double Blind Single Dose within-Subject Cross-over Design. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.C.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Brownell, K.D.; Foster, G.D.; Wadden, T.A. Albert J. (“Mickey”) Stunkard, M.D. Mickey. Obeisty 2014, 22, 1937–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J. Eating Patterns and Obesity. Psychiatr. Q. 1959, 33, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Devlin, M.; Walsh, B.T.; Hasin, D.; Wing, R.; Marcus, M.; Stunkard, A.; Wadden, T.; Yanovski, S.; Agras, S.; et al. Binge Eating Disorder: A Multisite Field Trial of the Diagnostic Criteria. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1992, 11, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Laederach-Hofmann, K.; Graf, C.; Horber, F.; Lippuner, K.; Lederer, S.; Michel, R.; Schneider, M. Imipramine and Diet Counseling with Psychological Support in the Treatment of Obese Binge Eaters: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Double- Blind Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 26, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, U.D.; Agras, W.S. Successful Treatment of Nonpurging Bulimia Nervosa with Desipramine: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alger, S.A.; Schwalberg, M.D.; Bigaouette, J.M.; Michalek, A.V.; Howard, L.J. Effect of a Tricyclic Antidepressant and Opiate Antagonist on Binge-Eating Behavior in Normoweight Bulimic and Obese, Binge-Eating Subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 53, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.D.; Wing, R.R.; Ewing, L.; Kern, E.; McDermott, M.; Gooding, W. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Fluoxetine plus Behavior Modification in the Treatment of Obese Binge-Eaters and Non-Binge-Eaters. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M.; Wilson, G.T. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Fluoxetine for the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Comparison. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.J.; Goldfein, J.A.; Petkova, E.; Jiang, H.; Raizman, P.S.; Walk, S.; Mayer, L.; Carino, J.; Bellace, D.; Kamenetz, C.; et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Fluoxetine as Adjuncts to Group Behavioral Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Welge, J.A.; Bennett, A.J.; Keck, P.E. A Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial of Fluoxetine in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Malhotra, S.; Welge, J.A.; Nelson, E.B.; Keck, P.E. Citalopram in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder: A Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.L.; Casuto, L.S.; Nelson, E.B.; Lake, K.A.; Soutullo, C.A.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Hudson, J.I. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sertraline in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leombruni, P.; Pierò, A.; Brustolin, A.; Mondelli, V.; Levi, M.; Campisi, S.; Marozio, S.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Fassino, S. A 12 to 24 Weeks Pilot Study of Sertraline Treatment in Obese Women Binge Eaters. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 21, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leombruni, P.; Pierò, A.; Lavagnino, L.; Brustolin, A.; Campisi, S.; Fassino, S. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial Comparing Sertraline and Fluoxetine 6-Month Treatment in Obese Patients with Binge Eating Disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I.; McElroy, S.L.; Raymond, N.C.; Crow, S.; Keck, P.E.; Carter, W.P.; Mitchell, J.E.; Strakowski, S.M.; Pope, H.G.; Coleman, B.S.; et al. Fluvoxamine in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder: A Multicenter Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 1756–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, T.; Spurell, E.; Hohlstein, L.A.; Gurney, V.; Read, J.; Fuchs, C.; Keller, M.B. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Fluvoxamine in Binge Eating Disorder: A High Placebo Response. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2003, 6, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Kotwal, R.; Hudson, J.I.; Nelson, E.B.; Keck, P.E. Zonisamide in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder: An Open-Label, Prospective Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Shapira, N.A.; Arnold, L.M.; Keck, P.E.; Rosenthal, N.R.; Wu, S.C.; Capece, J.A.; Fazzio, L.; Hudson, J.I. Topiramate in the Long-Term Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder Associated with Obesity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Capece, J.A.; Beyers, K.; Fisher, A.C.; Rosenthal, N.R. Topiramate for the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder Associated with Obesity: A Placebo-Controlled Study. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, A.M.; De Oliveira, I.R.; Appolinario, J.C.; Cordás, T.A.; Duchesne, M.; Sichieri, R.; Bacaltchuk, J. Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Topiramate plus Cognitive-Behavior Therapy in Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourredine, M.; Jurek, L.; Auffret, M.; Iceta, S.; Grenet, G.; Kassai, B.; Cucherat, M.; Rolland, B. Efficacy and Safety of Topiramate in Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Kotwal, R.; Guerdjikova, A.I.; Welge, J.A.; Nelson, E.B.; Lake, K.A.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Hudson, J.I. Zonisamide in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder with Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial Susan. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerdjikova, A.I.; McElroy, S.L.; Welge, J.A.; Nelson, E.; Keck, P.E.; Hudson, J.I. Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder with Obesity: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Monotherapy Trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Fischer, A.; Keller, U. Effect of Sibutramine and of Cognitive-Behavioural Weight Loss Therapy in Obesity and Subclinical Binge Eating Disorder. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2006, 8, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appolinario, J.C.; Bacaltchuk, J.; Sichieri, R.; Claudino, A.M.; Godoy-Matos, A.; Morgan, C.; Zanella, M.T.; Coutinho, W. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Sibutramine in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Crow, S.J.; Hudson, J.I.; Mitchell, J.E.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Blakesley, V.; Walsh, B.T.; Alger-Mayer, S.; Bartlett, S.; Fernstrom, M.; et al. Efficacy of Sibutramine for the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Randomized Multicenter Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milano, W.; Petrella, C.; Casella, A.; Capasso, A.; Carrino, S.; Milano, L. Use of Sibutramine, an Inhibitor of the Reuptake of Serotonin and Noradrenaline, in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Placebo-Controlled Study. Adv. Ther. 2005, 22, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krentz, A.J.; Fujioka, K.; Hompesch, M. Evolution of Pharmacological Obesity Treatments: Focus on Adverse Side-Effect Profiles. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Mitchell, J.E.; Wilfley, D.; Ferreira-Cornwell, M.C.; Gao, J.; Wang, J.; Whitaker, T.; JonasMD, J.; Gasior, M. Efficacy and Safety of Lisdexamfetamine for Treatment of Adults with Moderate to Severe Binge-Eating Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerdjikova, A.I.; Mori, N.; Blom, T.J.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Williams, S.L.; Welge, J.A.; McElroy, S.L. Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate in Binge Eating Disorder a Placebo Controlled Trial. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2016, 31, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I.; McElroy, S.L.; Ferreira-Cornwell, M.C.; Radewonuk, J.; Gasior, M. Efficacy of Lisdexamfetamine in Adults with Moderate to Severe Binge-Eating Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.I.; Grilo, C.M.; Guerdjikova, A.I.; Deng, L.; Koblan, K.S.; Goldman, R.; Navia, B.; Hopkins, S.; Loebel, A. Efficacy and Safety of Dasotraline in Adults with Binge-Eating Disorder: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Flexible-Dose Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Sunovion Discontinues Dasotraline Program. 2020. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Spettigue, W.; Norris, M.L.; Maras, D.; Obeid, N.; Feder, S.; Harrison, M.E.; Gomez, R.; Fu, M.C.Y.; Henderson, K.; Buchholz, A. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of Olanzapine as an Adjunctive Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescents: An Open-Label Trial. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drazen, J.M.; Curfman, G.D. Financial Associations of Authors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1901–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, C.P.; Gupta, A.R.; Krumholz, H.M. Disclosure of Financial Competing Interests in Randomised Controlled Trials: Cross Sectional Review. Br. Med. J. 2003, 326, 526–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.L.; Hudson, J.; Ferreira-Cornwell, M.C.; Radewonuk, J.; Whitaker, T.; Gasior, M. Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate for Adults with Moderate to Severe Binge Eating Disorder: Results of Two Pivotal Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.L.; Arnold, L.M.; Shapira, N.A.; Keck, P.E.; Rosenthal, N.R.; Karim, M.R.; Kamin, M.; Hudson, J.I. Topiramate in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder Associated with Obesity: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, P.K.; Calder, G.L.; Miller, K.K.; Misra, M.; Lawson, E.A.; Meenaghan, E.; Lee, H.; Herzog, D.; Klibanski, A. Psychotropic Medication Use in Anorexia Nervosa between 1997 and 2009. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Anderson, M.L.; Keiper, C.D.; Whynott, R.; Parker, L. Psychotropic Medications in Adult and Adolescent Eating Disorders: Clinical Practice versus Evidence-Based Recommendations. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2016, 21, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge, M.C.; Forman, S.F.; McKenzie, N.M.; Rosen, D.S.; Mammel, K.A.; Callahan, S.T.; Hehn, R.; Rome, E.S.; Kapphahn, C.J.; Carlson, J.L.; et al. Use of Psychopharmacologic Medications in Adolescents with Restrictive Eating Disorders: Analysis of Data from the National Eating Disorder Quality Improvement Collaborative. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Alañón Pardo, M.; Ferrit Martín, M.; Calleja Hernández, M.Á.; Morillas Márquez, F. Adherence of Psychopharmacological Prescriptions to Clinical Practice Guidelines in Patients with Eating Behavior Disorders. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 73, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerdjikova, A.I.; McElroy, S.L.; Winstanley, E.L.; Nelson, E.B.; Mori, N.; McCoy, J.; Keck, P.E.; Hudson, J.I. Duloxetine in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder with Depressive Disorders: A Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewis, Y.D.; Bergner, L.; Steinberg, H.; Bentley, J.; Himmerich, H. Pharmacological Studies in Eating Disorders: A Historical Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050594

Lewis YD, Bergner L, Steinberg H, Bentley J, Himmerich H. Pharmacological Studies in Eating Disorders: A Historical Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(5):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050594

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewis, Yael D., Lukas Bergner, Holger Steinberg, Jessica Bentley, and Hubertus Himmerich. 2024. "Pharmacological Studies in Eating Disorders: A Historical Review" Nutrients 16, no. 5: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050594

APA StyleLewis, Y. D., Bergner, L., Steinberg, H., Bentley, J., & Himmerich, H. (2024). Pharmacological Studies in Eating Disorders: A Historical Review. Nutrients, 16(5), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050594