The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

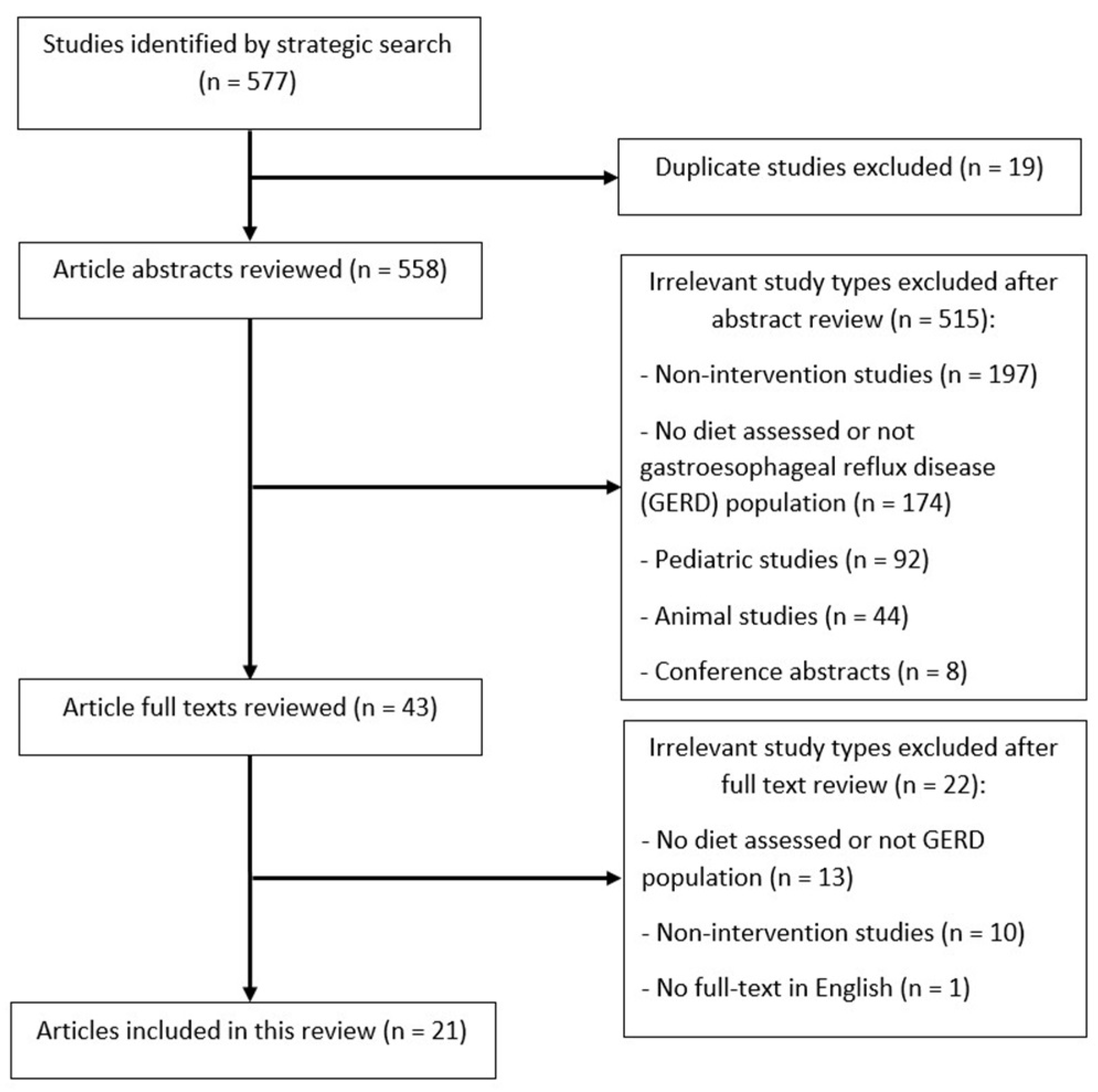

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Outcomes of the Studies

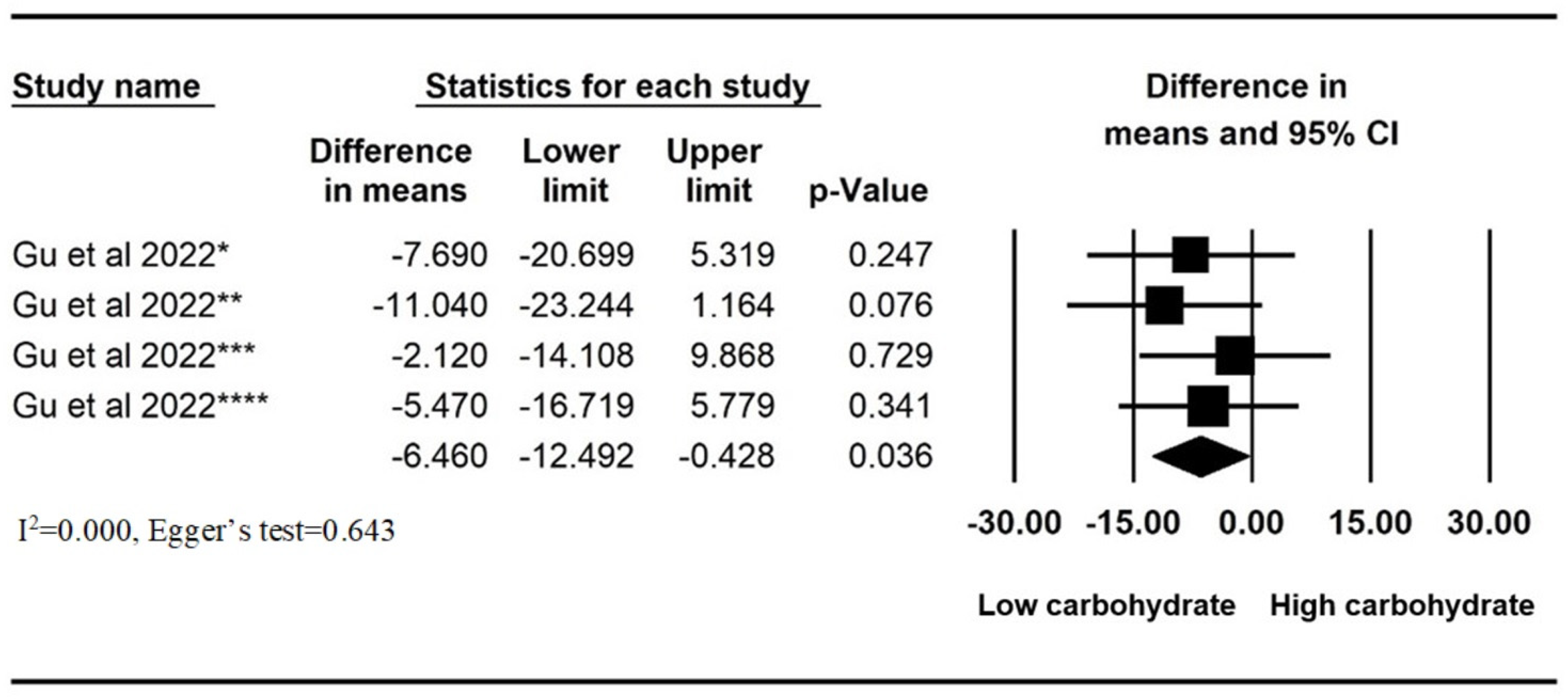

3.3. Low-Carbohydrate Diets

3.4. High-Fat Diets

3.5. Low-FODMAP Diets

3.6. Eating Speed

3.7. Other Dietary Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richter, J.E.; Rubenstein, J.H. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusebi, L.H.; Ratnakumaran, R.; Yuan, Y.; Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Bazzoli, F.; Ford, A.C. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: A meta-analysis. Gut 2018, 67, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Sweet, S.; Winchester, C.C.; Dent, J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review. Gut 2014, 63, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, P.O.; Dunbar, K.B.; Schnoll-Sussman, F.H.; Greer, K.B.; Yadlapati, R.; Spechler, S.J. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltenbach, T.; Crockett, S.; Gerson, L.B. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.S.; Song, M.; Staller, K.; Chan, A.T. Association Between Beverage Intake and Incidence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2226–2233.e2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Satia, J.A.; Rabeneck, L. Dietary intake and the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A cross sectional study in volunteers. Gut 2005, 54, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaidum, S.; Patcharatrakul, T.; Promjampa, W.; Gonlachanvit, S. The Effect of Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAP) Meals on Transient Lower Esophageal Relaxations (TLESR) in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Patients with Overlapping Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hou, Z.K.; Huang, Z.B.; Chen, X.L.; Liu, F.B. Dietary and Lifestyle Factors Related to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, Z.; Spry, G.; Hoult, J.; Maimone, I.R.; Tang, X.; Crichton, M.; Marshall, S. What is the efficacy of dietary, nutraceutical, and probiotic interventions for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 52, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins JP, G.S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.J.; Hou, Y.T.; Sun, X.H.; Li, X.Q.; Wang, Z.F.; Guo, M.; Zhu, L.M.; Wang, N.; Yu, K.; Li, J.N.; et al. Effect of high-fat, standard, and functional food meals on esophageal and gastric pH in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and healthy subjects. J. Dig. Dis. 2018, 19, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, G.L.; Thiny, M.T.; Westman, E.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Shaheen, N.J. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006, 51, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Kuo, C.M.; Yao, C.C.; Tai, W.C.; Chuah, S.K.; Lim, C.S.; Chiu, Y.C. The effect of dietary carbohydrate on gastroesophageal reflux disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Olszewski, T.; King, K.L.; Vaezi, M.F.; Niswender, K.D.; Silver, H.J. The Effects of Modifying Amount and Type of Dietary Carbohydrate on Esophageal Acid Exposure Time and Esophageal Reflux Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagini, R.; Mangano, M.; Bianchi, P.A. Effect of increasing the fat content but not the energy load of a meal on gastro-oesophageal reflux and lower oesophageal sphincter motor function. Gut 1998, 42, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, P.; Vauquelin, B.; Rolland, E.; Melchior, C.; Roman, S.; Bruley des Varannes, S.; Mion, F.; Gourcerol, G.; Sacher-Huvelin, S.; Zerbib, F. Low FODMAPs diet or usual dietary advice for the treatment of refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease: An open-labeled randomized trial. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, S.; Bayrakci, B.; Erdogan, A.; Yildirim, E.; Vardar, R. The influence of the speed of food intake on multichannel impedance in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013, 1, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valitova, E.R.; Bayrakci, B.; Bor, S. The effect of the speed of eating on acid reflux and symptoms of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 24, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, S.; Erdogan, A.; Bayrakci, B.; Yildirim, E.; Vardar, R. The impact of the speed of food intake on gastroesophageal reflux events in obese female patients. Dis. Esophagus 2017, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bove, M.; Lundell, L.; Ny, L.; Casselbrant, A.; Fandriks, L.; Pettersson, A.; Ruth, M. Effects of dietary nitrate on oesophageal motor function and gastro-oesophageal acid exposure in healthy volunteers and reflux patients. Digestion 2003, 68, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.d.S. Regression of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms using dietary supplementation with melatonin, vitamins and aminoacids: Comparison with omeprazole. J. Pineal Res. 2006, 41, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.G.; Tay, H.; Ho, K.Y. Curry induces acid reflux and symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 3546–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, Y.; Khedmat, H.; Valizadegan, G.; Mohtashami, R.; Sahebkar, A. Efficacy and safety of Aloe vera syrup for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A pilot randomized positive-controlled trial. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 35, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozov, S.; Isakov, V.; Konovalova, M. Fiber-enriched diet helps to control symptoms and improves esophageal motility in patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2291–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatani, A.; Vaher, K.; Rivero-Mendoza, D.; Alabasi, K.; Dahl, W.J. Fermented soy supplementation improves indicators of quality of life: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in adults experiencing heartburn. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, J.M.; Singh, N.K.; Phillips, J.; Kalpurath, K.; Taylor, K.; Stanley, R.A.; Eri, R.D. Anti-Heartburn Effects of Sugar Cane Flour: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triadafilopoulos, G.; Korzilius, J.W.; Zikos, T.; Sonu, I.; Fernandez-Becker, N.Q.; Nguyen, L.; Clarke, J.O. Ninety-Six Hour Wireless Esophageal pH Study in Patients with GERD Shows that Restrictive Diet Reduces Esophageal Acid Exposure. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Hagen, R.; Mitchell, M.; Ghareeb, E.; Fang, W.; Correa, R.; Zinn, Z.; Gayam, S. The effect of a low-nickel diet and nickel sensitization on gastroesophageal reflux disease: A pilot study. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 40, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Martinez, V.M.; Zavala-Solares, M.R.; Espinosa-Flores, A.J.; Leon-Barrera, K.L.; Alcantara-Suarez, R.; Carrillo-Ruiz, J.D.; Escobedo, G.; Roldan-Valadez, E.; Esquivel-Velazquez, M.; Melendez-Mier, G.; et al. Is a Non-Caloric Sweetener-Free Diet Good to Treat Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder Symptoms? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, B.; Izzo, L.; Mancino, N.; Pesce, M.; Rurgo, S.; Tricarico, M.C.; Lombardi, S.; De Conno, B.; Sarnelli, G.; Ritieni, A. Effect of Dewaxed Coffee on Gastroesophageal Symptoms in Patients with GERD: A Randomized Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piche, T.; Zerbib, F.; Varannes, S.B.; Cherbut, C.; Anini, Y.; Roze, C.; le Quellec, A.; Galmiche, J.P. Modulation by colonic fermentation of LES function in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2000, 278, G578–G584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piche, T.; des Varannes, S.B.; Sacher-Huvelin, S.; Holst, J.J.; Cuber, J.C.; Galmiche, J.P. Colonic fermentation influences lower esophageal sphincter function in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentilcore, D.; Chaikomin, R.; Jones, K.L.; Russo, A.; Feinle-Bisset, C.; Wishart, J.M.; Rayner, C.K.; Horowitz, M. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushref, M.A.; Srinivasan, S. Effect of high fat-diet and obesity on gastrointestinal motility. Ann. Transl. Med. 2013, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usai, P.; Manca, R.; Cuomo, R.; Lai, M.A.; Russo, L.; Boi, M.F. Effect of gluten-free diet on preventing recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease-related symptoms in adult celiac patients with nonerosive reflux disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 1368–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Yadlapati, R. Diagnosis and Management of Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rettura, F.; Bronzini, F.; Campigotto, M.; Lambiase, C.; Pancetti, A.; Berti, G.; Marchi, S.; de Bortoli, N.; Zerbib, F.; Savarino, E.; et al. Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Management Update. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 765061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellon, E.S.; Shaheen, N.J. Persistent reflux symptoms in the proton pump inhibitor era: The changing face of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 7–13.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Egger, M. Investigating and dealing with publication bias and other reporting biases in meta-analyses of health research: A review. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N.; Soleimani, D.; Hajiahmadi, S.; Moradi, S.; Heidarzadeh, N.; Nachvak, S.M. Dietary Intake in Relation to the Risk of Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 26, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, A.; Guido, D.; Grassi, M.; Riva, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E.; Perna, S.; Faliva, M.A.; Rondanelli, M. The Effect of Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) and Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus) Extract Supplementation on Functional Dyspepsia: A Randomised, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 915087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, M.S.K.; Nirvanashetty, D.S.; Parachur, B.V.A.; Krishnamoorthy, M.C.; Dey, M.S. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Parallel-Group, Comparative Clinical Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of OLNP-06 versus Placebo in Subjects with Functional Dyspepsia. J. Diet. Suppl. 2022, 19, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, D.T.; Ha, Q.V.; Nguyen, C.T.; Le, Q.D.; Nguyen, D.T.; Vu, N.T.; Dang, N.L.; Le, N.Q. Overlap of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Functional Dyspepsia and Yield of Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Patients Clinically Fulfilling the Rome IV Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 910929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Shiba, M.; Kohata, Y.; Yamagami, H.; Tanigawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Watanabe, T.; Tominaga, K.; Arakawa, T. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.; Barr, C.; Nolan, S.; Lomer, M.; Anggiansah, A.; Wong, T. The effects of dietary fat and calorie density on esophageal acid exposure and reflux symptoms. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser-Moodie, C.A.; Norton, B.; Gornall, C.; Magnago, S.; Weale, A.R.; Holmes, G.K. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 34, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerenziani, S.; Guarino, M.P.L.; Trillo Asensio, L.M.; Altomare, A.; Ribolsi, M.; Balestrieri, P.; Cicala, M. Role of Overweight and Obesity in Gastrointestinal Disease. Nutrients 2019, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Friedenberg, F. Obesity and GERD. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 43, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Study Type | Country | Sample Size | Population | Age (Years) | Gender (F/M, % F) | BMI (kg/m2) | Intervention | Duration of Intervention | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-carbohydrate diets | ||||||||||

| Austin et al., 2006 [14] | Single-arm intervention study | USA | 8 | GERD (symptoms) and obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | Mean (SD), 40 (10) | 8/0, 100% | Mean (SD), 43.5 (9.2) | Pre- and post- low-carbohydrate diet (<20 g/day) | 3–6 days | 1 |

| Wu et al., 2018 [15] | Non-randomized, cross-over | Taiwan | 12 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (SD), 43.5 (9.2) | 5/7, 71.4% | Mean (SD), 24.3 (3.8) | Low- vs. high-carbohydrate diets (84.8 g vs. 178.8 g) | One meal (6 h wash out period) | 2 |

| Gu et al., 2022 [16] | RCT | USA | 98 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (SD), 60 (12.5) | 16/79, 16.8% | Mean (SD), 32.7 h (5.4) | High total/high simple carbohydrate (HTHS), high total/low simple carbohydrate (HTLS), low total/high simple carbohydrate (LTHS), or low total/low simple carbohydrate (LTLS) diets | 9 weeks | 4 |

| High-fat diets | ||||||||||

| Penagini et al., 1998 [17] | RCT, cross-over | Italy | 14 | GERD (endoscopy and/or pH monitoring) 6 RE 8 abnormal pH monitoring | Range, 23–60 | 4/10, 28.6% | N/A | High-fat meal vs. balanced meal | One meal (2-day wash out period) | 2 |

| Fan et al., 2018 [12] | RCT, cross-over | China | 27 | GERD (symptoms) 15 RE 12 NERD | RE: mean (SD), 50.9 (7.5) NERD: mean (SD), 46.8 (11.3) | RE 9/6, 60% NERD 5/7, 41.7% | RE: mean (SD), 24.4 (2.2) NERD: mean (SD), 23.3 (1.5) | High-fat meal vs. standard meal | One meal (5 h and 17.5 h wash out period) | 3 |

| Low-FODMAP diets | ||||||||||

| Rivière et al., 2021 [18] | RCT | France | 31 | GERD (symptoms) and PPI refractory | Median (range), 45 (39–51) | 17:14, 55% | N/A | Low-FODMAP diet vs. usual dietary advice | 4 weeks | 3 |

| Plaidum et al., 2022 [8] | RCT, cross-over | Thailand | 8 | GERD (symptoms) and overlapping IBS (non-constipation) | Mean (SD), 57 (13) | 6:2, 75% | Mean (SD), 23.3 (2.7) | Rice noodle vs. wheat noodle meals for breakfast and lunch | Two meals (1-week wash out period) | 3 |

| Eating speed | ||||||||||

| Bor et al., 2013 [19] | RCT, cross-over | Turkey | 46 | GERD (symptoms) | Median, 43 | 32/14, 69.6% | N/A | 5 min vs. 30 min | One meal (1-day wash out period) | 2 |

| Valitova et al., 2013 [20] | RCT, cross-over | Turkey | 60 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (SD), 43.5 (10.8) | 39/21, 65% | N/A | 5–10 min vs. 25–30 min | One meal (1-day wash out period) | 2 |

| Bor et al., 2017 [21] | RCT, cross-over | Turkey | 26 | GERD (symptoms) and obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | Mean (SD), 46 (12) | 26/0, 100% | Mean (SD), 39.9 (8.4) | 5 min vs. 30 min | One meal (1-day wash out period) | 2 |

| Other dietary interventions | ||||||||||

| Bove et al., 2003 [22] | RCT, cross-over | Sweden | 9 | GERD (symptoms and pH monitoring) | Median (range), 40 (25–54) | 4/5, 44.4% | N/A | High-nitrate vs. nitrate-free diets | 4 days (2-week wash out period) | 4 |

| Pereira et al., 2006 [23] | RCT | Brazil | 351 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (range), 44 (18–88) | 210/141, 59.8% | N/A | Dietary supplementation containing melatonin, l-tryptophan, vitamin B6, folic acid, vitamin B12, methionine, and betaine vs. 20 mg omeprazole | 40 days | 3 |

| Lim et al., 2011 [24] | Single-arm intervention study | Singapore | 25 | GERD (symptoms and endoscopy) NERD | Mean (SD), 44.8 (2.4) | 2/23, 8% | N/A | Pre- and post- curry ingestion | One meal | 6 |

| Panahi et al., 2015 [25] | RCT | Iran | 79 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (SD), 47 (17) | 45/34, 57% | Mean (SD), 25.4 (4.5) | Aloe vera vs. omeprazole vs. ranitidine | 4 weeks | 3 |

| Fan et al., 2018 [12] | RCT, cross-over | China | 27 | GERD (symptoms) 15 RE 12 NERD | RE: mean (SD), 50.9 (7.5) NERD: mean (SD), 46.8 (11.3) | RE 9/6, 60% NERD 5/7, 41.7% | RE: mean (SD), 24.4 (2.2) NERD: mean (SD), 23.3 (1.5) | Functional food vs. standard meal | One meal (5 h and 17.5 h wash out period) | 3 |

| Morozov et al., 2018 [26] | Single-arm intervention study | Russia | 30 | GERD (symptoms and endoscopy) NERD with low dietary fiber intake | Mean (SD), 34.7 (9.3) | 12/18, 40% | Mean (SD), 26.7 (6.9) | Pre- and post- psyllium 15 g per day | 10 days | 3 |

| Fatani et al., 2020 [27] | RCT | USA | 51 | GERD (symptoms) | Intervention: median (range), 30 (18–55) Control: median (range), 24 (19–56) | 37/14, 72.5% | N/A | Fermented soy vs. placebo | 3 weeks | 5 |

| Beckett et al., 2020 [28] | RCT | Australia | 40 | GERD (symptoms) | Mean (SD), 46.0 (12.6) | 26/14 (65%) | Mean (SD), 32.6 (8.7) | Sugar cane flour vs. placebo | 3 weeks | 5 |

| Triadafilopoulos et al., 2020 [29] | Single-arm intervention study | USA | 66 | GERD (symptoms) 34 normal AET 32 abnormal AET | Median (range), 51 (20–87) | 36/30, 54% | Normal AET: mean (SE), 24.7 (1.9) Abnormal AET: mean (SE), 26 (1.1) | Pre- and post- restricted (anti-reflux) diet | 2 days | 3 |

| Yousaf et al., 2021 [30] | Single-arm intervention study | USA | 20 | GERD (symptoms) and PPI refractory | Mean (SD), 49.95 (12.74) | 16/4, 80% | Mean (SD), 35.24 (9.04) | Pre- and post- low-nickel diet | 8 weeks | 2 |

| Mendoza-Martínez et al., 2022 [31] | RCT | Mexico | 95 | GERD (symptoms) | non-caloric sweeteners (NCS): mean (SD), 22 (3.1) Non-caloric sweetener-free diet (NCS-f): mean (SD), 22 (3.2) | 58/37, 61% | NCS: mean (SD), 23.9 (3.1) NCS-f: mean (SD), 24.16 (3.8) | NCS vs. NCS-f | 5 weeks | 3 |

| Polese et al., 2022 [32] | RCT, cross-over | Italy | 40 | GERD (symptoms) and 50% of time following coffee consumption | Mean (SD), 41.5 (12) | 16/24, 40% | Mean (SD), 25.5 (4) | Standard coffee vs. dewaxed coffee | 2 weeks (2-week wash out period) | 3 |

| Study | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GERD Symptoms | pH Monitoring Measurement | Quality of Life | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diets | |||||

| Austin et al., 2006 [14] | Pre- and post-low-carbohydrate diet (daily carbohydrate intake < 20 g/day) for 3–6 days | N/A | - Significant decrease in the GERD Symptom Assessment Scale–Distress Subscale (GSAS-ds) score after low-carbohydrate diet (mean (SE), 1.28 (0.15) vs. 0.72 (0.12); p = 0.0004) | - Significant decrease in 24 h esophageal acid exposure time (AET) after low-carbohydrate diet (mean (SE), 5.1% (1.3) vs. 2.5% (0.6); p = 0.022) - Significant decrease in Johnson–DeMeester Score after a low-carbohydrate diet. (mean (SE), 34.7 (10.1) vs. 14.0 (3.7); p = 0.023) | N/A |

| Wu et al., 2018 [15] | Low-carbohydrate diet, 500 mL liquid meal (474.4 kcal, 10.4 g protein, 10.4 g fat, 84.8 g carbohydrate) | High-carbohydrate diet, 500 mL liquid meal (850.4 kcal,10.4 g protein, 10.4 g fat, 178.8 g carbohydrate) | - Higher heartburn and acid regurgitation post high-carbohydrate diet | - Higher Johnson–DeMeester scores post high-carbohydrate diet (mean (SD), 39.7 (11.0) vs. 14.3 (5.3); p = 0.019) - Higher numbers of reflux periods post high-carbohydrate diet (mean (SD), 12.7 (2.1) vs. 7.1 (2.3); p = 0.026) | N/A |

| Gu et al., 2022 [16] | High total/low simple carbohydrate (HTLS), low total/high simple carbohydrate (LTHS), and low total/low simple carbohydrate (LTLS) diets for 9 weeks | High total/high simple carbohydrate diet (HTHS) for 9 weeks | - Significant reduction in total GERD-Q score between pre- and post intervention within HTLS (mean (SD), −3.1 (3.6)), LTHS (−3.7 (3.4)) and LTLS (−3.5 (3.9)), non-significant reduction in HTHS (−1.4 (1.1)) | - Significant reduction in AET between pre- and post intervention within HTLS (median (interquartile range (IQR), −3.0% (1.3 to −6.2)) and LTHS (−2.7% (0.5 to −6.6)), non-significance in HTHS (0.5% (−1.0 to 3.7) and LTLS (0.6% (−1.0 to 3.5). - Significant reduction in total reflux episodes between pre- and post intervention within HTLS (median (IQR), −14.8 (−56.8 to 12.0)) and LTHS (−12.7 (−64.2 to 14.0)), non-significance in HTHS (18.7 (−30.0 to 77.5)) and LTLS (6.0 (−14.4 to 31.6)). | N/A |

| High-fat diets | |||||

| Penagini et al., 1998 [17] | High-fat meal (44 g fat) Carbohydrate (C): Fat (F): Protein (P), 39:52:9% 760 kcal, 450 mL (150 mL Ensure, 150 mL lipofundin, 150 mL saline) Infused 40 mL/min into stomach Plus eating 1 sandwich and 150 mL Ensure Position: 7 recumbent and 7 sitting | Balanced meal (20 g fat) C:F:P 60:24:16% 755 kcal, 450 mL (450 mL Ensure) Infused 40 mL/min into stomach Plus eating 1 sandwich and 150 mL Ensure Position: 7 recumbent and 7 sitting | N/A | - No significant difference in transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESR) between groups - No significant difference in Basal lower esophageal pressure between groups - No significant difference in AET at 3 h between groups: recumbent (mean (SE): 16.5% (7.5) vs. 19.5% (6.5) sitting (mean (SE): 6.3% (2.4) vs. 8.6% (2.9) - No significant difference in rate of reflux episodes per hour recumbent (mean (SE): 5.2 (1.9) vs. 4.8 (1.7) sitting (mean (SE): 2.4 (0.7) vs. 3.9 (1.1) | N/A |

| Fan et al., 2018 [12] | High-fat meal (53.7 g fat) C:F:P, 29.1:60.6:9.3% 800 kcal, 800 mL Position: upright | Standard meal (22.2 g fat) C:F:P 12.3:25:62.6% 800 kcal, 800 mL Position: upright | - No significant difference in number of postprandial reflux symptoms RE group (median (IQR): 1 (0–1) vs. 1 (0–2) NERD group (median (IQR): 1 (0–2) vs. 3 (1–4) | - Significant difference in AET at 4 h RE group: (median (IQR): 5.2% (0.5–22.4) vs. 4.0% (0–10.5) - No significant difference in percentage of time pH < 4 in gastric fundus | N/A |

| Low-FODMAP diets | |||||

| Rivière et al., 2021 [18] | Low-FODMAP diet for 4 weeks | Usual dietary advice for 4 weeks | - No significant difference in reduction in a Reflux Disease Questionnaire (RDQ) score ≤ 3 between two groups (37.5% vs. 20%; p = 0.43) | - No significant difference in total acid exposure between two groups (median (IQR), 0.9 (0.0–1.9) vs. 1.0 (0.2–2.0); p = 0.88) - No significant difference in total reflux events between two groups (median (IQR), 46 (35–61) vs. 51 (28–99); p = 0.41) | N/A |

| Plaidum et al., 2022 [8] | Rice noodle meal (low FODMAPs) for breakfast and lunch | Wheat noodle meal (high FODMAPs) for breakfast and lunch | - Significantly higher regurgitation severity scores after wheat meal compared to rice meal (median (IQR), 1.5 (0.0–6.1) vs. 0.3 (0.0–0.9); p < 0.05) | - Significantly higher number of TLESR events in the 2 h after wheat meal compared to rice meal (mean (SD), 5.00 (0.68) vs. 1.88 (0.30); p = 0.01) | N/A |

| Eating speed | |||||

| Bor et al., 2013 [19] | 5 min Standard meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) 744 kcal C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | 30 min Standard meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) 744 kcal C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | N/A | - No significant difference in total reflux events in 3 h (number, 753 vs. 733) - No significant difference of reflux events in the first, second, and third hour | N/A |

| Valitova et al., 2013 [20] | 5–10 min (mean (SD) 8.4 (2.4) minutes) Balanced meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | 25–30 min (mean (SD) 27.7 (4) minutes) Balanced meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | - No significant difference in reflux symptoms in 3 h (heartburn or regurgitation) All patients: number 100 vs. 113 Pathologic pH monitoring patients: number 48 vs. 54 | N/A | N/A |

| Bor et al., 2017 [21] | 5 min Standard meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) 744 kcal C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | 30 min Standard meal (a double cheeseburger, 1 banana, 100 g yogurt, and 200 mL water) 744 kcal C:F:P = 37.6:41.2:21.2% | N/A | - No significant difference in total reflux events in 3 h All patients: number (mean), 715 (11.9) vs. 668 (11.1) Pathologic pH monitoring patients: number (mean), 418 (19.0) vs. 418 (19.0) - No significant difference in total reflux time in 3 h All patients: minutes (mean), 1007 (16.8) vs. 866 (14.4) Pathologic pH monitoring patients: minutes (mean), 716 (32.5) vs. 627 (28.5) | N/A |

| Other dietary interventions | |||||

| Bove et al., 2003 [22] | Nitrate capsule for lunch and dinner (200 mg, 50% recommended dose and 3–4 times the mean nitrate in Swedish diets) Plus nitrate/nitrite-free diet for 4 days | Placebo capsule for lunch and dinner Plus nitrate/nitrite-free diet for 4 days | N/A | - No significant difference in TLESR time (second) between groups Supine: mean (SD), 92.1 (78.3) vs. 93.9 (46.1) Sitting after gastric distension: mean (SD), 183.9 (79.9) vs. 103.9 (85.7) - No significant difference in number of TLESR in 30 min Supine: mean (SD), 4.9 (4.3) vs. 4.9 (2.5) Sitting after gastric distension: mean (SD), 8.0 (3.1) vs. 6.6 (6.2) - No significant difference in AET (mean (SD), 6.0% (4.1) vs. 7.4% (7.4) - No significant difference in number of reflux episodes (mean (SD), 39 (22.5) vs. 35 (17.5) | N/A |

| Pereira et al., 2006 [23] | Dietary supplement (melatonin (6 mg), tryptophan (200 mg), vitamin B12 (50 lg), methionine (100 mg), vitamin B6 (25 mg), betaine (100 mg), and folic acid (10 mg)) for 40 days | 20 mg omeprazole for 40 days | - Significant reduction in symptoms in the dietary supplement group (100% vs. 65.7%; p = 0.001) | N/A | N/A |

| Lim et al., 2011 [24] | 400 mL (15 patients) or 800 mL (10 patients) of cooked curry suspension ingested over 5 min | N/A | - Significant higher total symptom score of 6 GERD symptoms (each analog scale 0–10) after curry ingestion at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 min (p < 0.005), non-significance at 180 min - Significant higher total symptom score after 800 mL curry ingestion compared to 400 mL (mean (SD) 14.1 (3.7) vs. 3.3 (1.0) at 180 min; p < 0.05 | - Significant higher AET at 3 h after curry ingestion Pre- vs. post- 400 mL: mean (SD), 5.4 (1.2) vs. 11.8 (2.2); p = 0.007 Pre- vs. post- 800 mL: mean (SD), 6.4 (3.3) vs. 20.5 (6.8); p = 0.007 Pre- vs. post- overall: mean (SD), 5.8 (1.4) vs. 15.3 (3.1); p < 0.001 | N/A |

| Panahi et al., 2015 [25] | Aloe vera syrup (10 mL once a day) for 4 weeks | Omeprazole (20 mg once a day) or ranitidine tablet (150 mg twice a day) for 4 weeks | - Significant reduction in the frequency of heartburn and regurgitation in all groups but less reduction in heartburn in the aloe vera group | N/A | N/A |

| Fan et al., 2018 [12] | Functional food (22.4 g fat) C:F:P14.6:25:60.4% 800 kcal, 800 mL Position: upright | Standard meal (22.2 g fat) C:F:P 12.3:25:62.6% 800 kcal, 800 mL Position: upright | - Significantly lower number of postprandial reflux symptoms after functional food in NERD group (median (IQR), 0 (0–1) vs. 3 (1–4)), but non-significance in RE group (median (IQR), 1 (0–2) vs. 1 (0–2)) | - No significant difference in AET at 4 h between 2 groups (median (IQR), 4.3 (0–26.5) vs. 4.0 (0–10.5)) - No significant difference in percentage of time pH < 4 in gastric fundus between 2 groups | N/A |

| Morozov et al., 2018 [26] | Psyllium 15 g per day for 10 days | N/A | - Significant improvement of heartburn in 60% of patients and decreased GERD-Q scores after psyllium ingestion (mean (SD)), 10.9 (1.7) vs. 6.0 (2.3)) | - Significant reduction in the number of reflux episodes after psyllium ingestion (mean (SD), 67.9 (17.7) vs. 42.4 (13.5); p < 0.001) without change of 24 h pH below 4 | N/A |

| Fatani et al., 2020 [27] | Fermented soy (1 sachet) after heartburn symptoms, can repeat with second dose if heartburn persists after 30 min, and can repeat with third dose or OTC medication if heartburn persists after 30 min, for 3 weeks | Maltodextrin (1 sachet) after heartburn symptoms, can with repeat second dose if heartburn persists after 30 min, and can repeat with third dose or OTC medication if heartburn persists after 30 min, for 3 weeks | - No significant difference in heartburn severity after ingestion at 5, 15, 30 min, evaluated by Likert-like scale - No significant difference in heart burn frequency (number per week) between baseline and intervention | N/A | - Significantly better GERD quality of life score in some items compared between intervention and baseline: “I found it inconvenient to have to take medications regularly because of acid reflux and heartburn symptoms” (mean (SD), − 1.0 (1.3) vs. − 0.04 (1.8); p < 0.05) “I was afraid to eat too much because of acid reflux and heartburn symptoms” (mean (SD), − 1.4 (1.3) vs. −0.2 (1.7); p < 0.05) “I was unable to concentrate on my work because of acid reflux and heartburn symptoms” (mean (SD), − 0.9 (1.6) vs. −0.3 (1.0); p < 0.05) “Acid reflux and heartburn symptoms disturbed my after-meal activities or rest” (mean (SD), − 1.6 (1.5) vs. −0.7 (1.5); p < 0.05) - No significant difference in overall score |

| Beckett et al., 2020 [28] | 3 g/day of prebiotic whole-plant sugarcane flour (PSCF) after morning and evening meal for 3 weeks | 3 g/day of cellulose after morning and evening meal for 3 weeks | - Significantly higher number of patients with improved heartburn symptoms in PSCF group (13 (65%) vs. 5 (25%); p = 0.039) - Significantly higher number of patients with improved regurgitation symptoms in PSCF group (11 (55%) vs. 1 (5%); p = 0.001) - Significantly higher number of patients with improved total Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Health Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) symptom scores in PSCF group (13 (65%) vs. 4 (20%); p = 0.015) - Significantly higher GERD-HRQL after PSCF ingestion Heartburn score: −2.2; 95% CI −4.2 to −0.14; p = 0.037 Total symptom score: −3.7; 95% CI −7.2 to −0.11; p = 0.044 | N/A | N/A |

| Triadafilopoulos et al., 2020 [29] | Restricted (anti-GER) diet through provided instructions and diet recommendations | N/A | - No significant difference in symptoms | - Significant reduction in AET at 48 h after the restricted diet in patients with abnormal AET (median, 10.5% (95% CI 8.9–12.6) vs. 4.5% (95% CI 3.1–7.3); p = 0.001), but non-significance in patients with normal AET (median, 3.2% (95% CI 1.9–4.0) vs. 2.6% (95% CI 0.8–3.4)) | N/A |

| Yousaf et al., 2021 [30] | low-nickel diet for 8 weeks | N/A | - Significant decrease in total GERD-HRQL, heartburn, and regurgitation scores | N/A | N/A |

| Mendoza-Martinez et al., 2022 [31] | Non-caloric sweetener-free (NCS-f) diet with less than 10 mg/day non-caloric sweetener (NCS) | NCS diet with 50–100 mg/day NCS (80% sucralose and 20% aspartame, acesulfame K, and saccharin) | - Significant improvement of burning and retrosternal pain in the NCS-f group (15% of participants in pre-treatment to 0% of post-treatment; p = 0.02) | N/A | N/A |

| Polese et al., 2022 [32] | Dewaxed coffee (DC) for 2 weeks | Standard coffee (SC) for 2 weeks | - Significant increase in both heartburn-free days and regurgitation-free days during DC compared to SC | N/A | - Significant improvement in quality of life in DC compared to SC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lakananurak, N.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Susantitaphong, P.; Patcharatrakul, T.; Gonlachanvit, S. The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030464

Lakananurak N, Pitisuttithum P, Susantitaphong P, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients. 2024; 16(3):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030464

Chicago/Turabian StyleLakananurak, Narisorn, Panyavee Pitisuttithum, Paweena Susantitaphong, Tanisa Patcharatrakul, and Sutep Gonlachanvit. 2024. "The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies" Nutrients 16, no. 3: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030464

APA StyleLakananurak, N., Pitisuttithum, P., Susantitaphong, P., Patcharatrakul, T., & Gonlachanvit, S. (2024). The Efficacy of Dietary Interventions in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients, 16(3), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030464