Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Association with Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior (Discrepancy between Self-Perceived and Actual Diet Quality): A Cross-Sectional Study among Spanish University Students of Both Genders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Overview

2.2. Setting and Participants

- (1)

- Interested students were provided with a personal alphanumeric code in class;

- (2)

- All documents related to the study were available on an educational platform used by the University of Seville. This educational platform is separate for each classroom (with access limited only to the students and professors of each classroom). The documents available to students on the educational platform were as follows: (a) Informed consent; (b) Initial form (see 2.3. Initial Form subsection); (c) User manual with detailed information for downloading and using e12HR, an application that is free to download from the App Store or Play Store. The documents (a) & (b) were to be filled out and submitted on the educational platform; in each of the two documents, each student had to include his or her personal alphanumeric code;

- (3)

- The research team reviewed the documents (a) and (b) after these were returned to the educational platform. When both documents were filled out correctly, the research team activated the personal alphanumeric code so that the corresponding student had access to the e12HR application (in this way, students could not start using the e12HR application until they had completed the two documents required for the research). Once the personal alphanumeric code was activated by the research team, the student only had to open the e12HR application to start using it (see Section 2.4. e-12HR Application subsection).

2.3. Initial Form

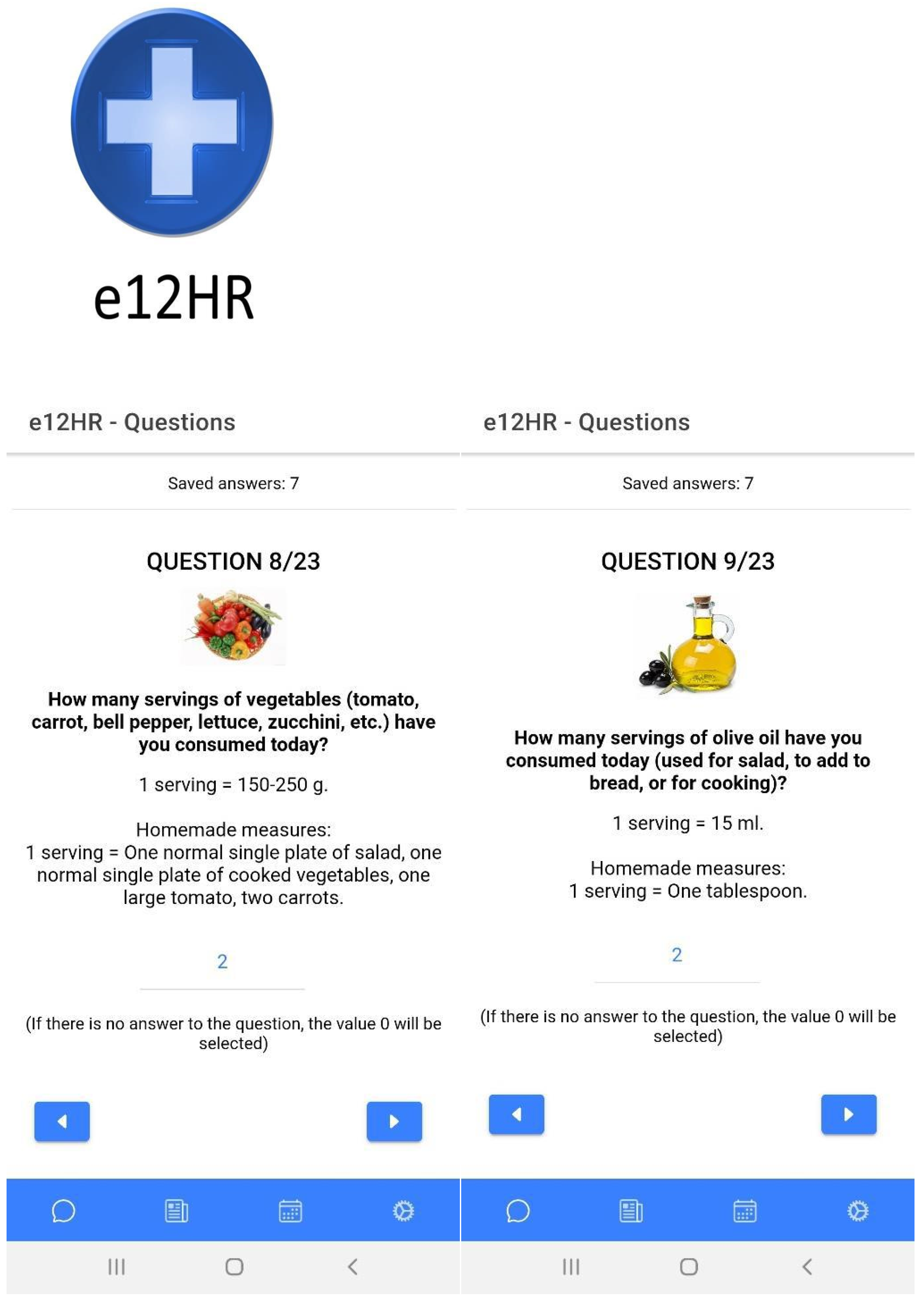

2.4. e12HR Application

2.5. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet Assessment

2.6. Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior by Students: Overestimation or Normal/Underestimation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Adherence to the Study

3.2. Personal Information of the Participants

3.3. Scores and Levels of the Mediterranean Diet Serving Score Index

3.4. Distribution of Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior by Students: Overestimation or Normal/Underestimation

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

- (1)

- (2)

- The self-perception of dietary behavior in the sample was significantly higher: the mean score of the self-perceived MDSS index was 14.3 for all students (14.3 for women and men) (Table 3), with 95.7% of all students at the moderate-high level of self-perceived MDSS index (95.5% for women and 96.4% for men) (Table 4);

- (3)

- The vast majority of the sample overestimated dietary behavior: 98.6% of all students were in the overestimation category (99.1% for women and 96.4% for men) (Table 5);

- (4)

- As we hypothesized, an overestimated self-perception of dietary behavior in the sample (that is, self-perceiving greater AMD than that associated with their actual dietary behavior) was associated with a lower AMD: The mean score of the MDSS index was significantly higher among students falling into the normal/underestimation category (12.0) compared to the overestimation category (6.7). Within the overestimation category, the mean score of the MDSS index grew significantly lower when moving from the low overestimation subcategory (8.1) to the moderate overestimation subcategory (6.7) and to the high overestimation subcategory (4.9). A similar trend was observed in women, with the following mean scores of the MDSS index by categories and subcategories: normal/underestimation category (13.0), overestimation category (6.7); within the overestimation category, low overestimation subcategory (8.2), moderate overestimation subcategory (6.7), and high overestimation subcategory (4.5) (Table 6). Comparisons of the normal/underestimation category versus the overestimation category must be made with caution, due to the small number of students in the normal/underestimation category (Table 5). The comparisons (between categories and subcategories) of the mean scores of the MDSS index were not statistically significant in men (Table 6); however, these comparisons must be made with caution, owing to the small number of male students (Table 2) currently enrolled at the University of Seville, Faculties of Health [30], which is actually a reflection of the small proportion of male students (28.2%).

4.2. Comparison with Prior Work

4.3. Comparison of Dietary Information: Initial Form Versus e12HR Application

4.4. Selected Sample: Health Sciences University Students

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Research Related to the Current Study

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | adherence to the Mediterranean diet |

| BMI | body mass index |

| FFQ | food frequency questionnaire |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

| MDSS | Mediterranean diet serving score |

| OLPPD | Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data |

| SD | standard deviation |

Appendix A

| Food Group | Recommendation Yes; I Have Complied with the Recommendation | I have Not Complied with the Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Daily consumption recommendations | ||

| Fruits | >3 serving/day | |

| Vegetables | 3 serving/day | |

| Cereals | 3–6 serving/day | |

| Olive oil | 3–4 serving/day | |

| Milk and dairy products | 2–3 serving/day | |

| Fermented beverages | 1–2 serving/day | |

| Weekly consumption recommendations | ||

| Nuts | 3–7 serving/week | |

| Potatoes | 3 serving/week | |

| Legumes | 2 serving/week | |

| Eggs | 3–4 serving/week | |

| Fish | 2 serving/week | |

| White meat | 2–3 serving/week | |

| Red and processed meat | 2 serving/week | |

| Sweets | 2 serving/week |

References

- Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M. Mediterranean Diet: From a Healthy Diet to a Sustainable Dietary Pattern. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Arija-Val, V.V.; Maíz-Aldalur, E.; Martínez de Victoria-Muñoz, E.; Ortega-Anta, R.M.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Quiles-Izquierdo, J.; Rodríguez-Martín, A.; Román-Viñas, B.; Salvador-Castell, G.; et al. Guías alimentarias para la población española (SENC, diciembre 2016); la nueva pirámide de la alimentación saludable [Dietary guidelines for the Spanish population (SENC, December 2016); the new graphic icon of healthy nutrition]. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gotsis, E.; Anagnostis, P.; Mariolis, A.; Vlachou, A.; Katsiki, N.; Karagiannis, A. Health benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: An update of research over the last 5 years. Angiology 2015, 66, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventriglio, A.; Sancassiani, F.; Contu, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Di Slavatore, M.; Fornaro, M.; Bhugra, D. Mediterranean Diet and its Benefits on Health and Mental Health: A Literature Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2020, 16, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lăcătușu, C.M.; Grigorescu, E.D.; Floria, M.; Onofriescu, A.; Mihai, B.M. The Mediterranean Diet: From an Environment-Driven Food Culture to an Emerging Medical Prescription. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Meller, S. Can we say what diet is best for health? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; La Vecchia, C.; Capone, R.; Medina, F.X.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Belahsen, R.; Burlingame, B.; Calabrese, G.; et al. Med Diet 4.0: The Mediterranean diet with four sustainable benefits. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, E.M.; Dernini, S.; Burlingame, B.; Meybeck, A.; Conforti, P. Food security and sustainability: Can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2012; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Lacirignola, C.; Capone, R. Mediterranean Food Consumption Patterns Diet, Environment, Society, Economy and Health; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2015; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable diets: The Mediterranean diet as an example. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2285–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, R.; Bach-Faig, A.; Raidó Quintana, B.; Buckland, G.; Vaz de Almeida, M.D.; Serra-Majem, L. Worldwide variation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, in 1961-1965 and 2000-2003. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Closas, R.; Berenguer, A.; González, C.A. Changes in food supply in Mediterranean countries from 1961 to 2001. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vareiro, D.; Bach-Faig, A.; Raidó-Quintana, B.; Bertomeu, I.; Buckland, G.; Vaz de Almeida, M.D.; Serra-Majem, L. Availability of Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean foods during the last four decades: Comparison of several geographical areas. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Muñoz, L.M.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Graciani, A.; López-García, E.; Mesas, A.E.; Aguilera, M.T.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern has declined in Spanish adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Liu, J.; Cheskin, L.J.; Sheppard, V.B. Discrepancy between perceived diet quality and actual diet quality among US adult cancer survivors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggi, C.; Biasini, B.; Ogrinc, N.; Strojnik, L.; Endrizzi, I.; Menghi, L.; Khémiri, I.; Mankai, A.; Slama, F.B.; Jamoussi, H.; et al. Drivers and Barriers Influencing Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet: A Comparative Study across Five Countries. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, A.; Vitiello, V.; Giusti, A.M.; Pinto, A.; Donini, L.M.; Del Balzo, V. Environmental and economic sustainability of the Mediterranean diet. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, L.; Chambaron, S.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Nicklaus, S. The motivational roots of sustainable diets: Analysis of food choice motives associated to health, environmental and socio-cultural aspects of diet sustainability in a sample of French adults. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 5, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubini, A.; Vilaplana-Prieto, C.; Flor-Alemany, M.; Yeguas-Rosa, L.; Hernández-González, M.; Félix-García, F.J.; Félix-Redondo, F.J.; Fernández-Bergés, D. Assessment of the Cost of the Mediterranean Diet in a Low-Income Region: Adherence and Relationship with Available Incomes. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghi, L.; Endrizzi, I.; Cliceri, D.; Zampini, M.; Giacalone, D.; Gasperi, F. Validating the Italian version of the Adult Picky Eating Questionnaire. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 101, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.R.; Luna-Castro, J.; Ballesteros-Yáñez, I.; Pérez-Ortiz, J.M.; Gómez-Romero, F.J.; Redondo-Calvo, F.J.; Alguacil, L.F.; Castillo, C.A. Influence of biomedical education on health and eating habits of university students in Spain. Nutrition 2021, 86, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Meseguer, M.J.; Burriel, F.C.; García, C.V.; Serrano-Urrea, R. Adherence to Mediterranean diet in a Spanish university population. Appetite 2014, 78, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Cuesta, J.Y.; Montoro-García, S.; Sánchez-Macarro, M.; Carmona-Martínez, M.; Espinoza-Marenco, I.C.; Pérez-Camacho, A.; Martínez-Pastor, A.; Abellán-Alemán, J. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in first-year university students and its association with lifestyle-related factors: A cross-sectional study. Hipertens. Riesgo Vasc. 2023, 40, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telleria-Aramburu, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Risk factors of overweight/obesity-related lifestyles in university students: Results from the EHU12/24 study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto-Arias, J.J.; Lorenzo, T.; Lamas, A.; Regal, P.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Cepeda, A. Food patterns and nutritional assessment in Galician university students. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 74, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Lacoba, R.; Pardo-Garcia, I.; Amo-Saus, E.; Escribano-Sotos, F. Socioeconomic, demographic and lifestyle-related factors associated with unhealthy diet: A cross-sectional study of university students. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Universidades, Gobierno de España. Datos y Cifras del Sistema Universitario Español Publicación 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.universidades.gob.es/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Béjar, L.M.; Reyes, Ó.A.; García-Perea, M.D. Electronic 12-Hour Dietary Recall (e-12HR): Comparison of a Mobile Phone App for Dietary Intake Assessment with a Food Frequency Questionnaire and Four Dietary Records. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar, L.M.; García-Perea, M.D.; Reyes, Ó.A.; Vázquez-Limón, E. Relative Validity of a Method Based on a Smartphone App (Electronic 12-Hour Dietary Recall) to Estimate Habitual Dietary Intake in Adults. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejar, L.M. Weekend–Weekday Differences in Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among Spanish University Students. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo, C.; Mariscal-Arcas, M.; Rivas, A.; Lorenzo-Tovar, M.L.; Tur, J.A.; Olea-Serrano, F. Proposal of a Mediterranean Diet Serving Score. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiloglou, M.F.; Lu, Y.; Stathopoulou, T.; Papathanail, I.; Fäh, D.; Ghosh, A.; Baumann, M.; Mougiakakou, S. Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence with the Smartphone: The Medipiatto Project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjar, L.M.; García-Perea, M.D.; Mesa-Rodríguez, P. Evaluation of an Application for Mobile Telephones (e-12HR) to Increase Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in University Students: A Controlled, Randomized and Multicentric Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjar, L.M.; Mesa-Rodríguez, P.; Quintero-Flórez, A.; Ramírez-Alvarado, M.D.M.; García-Perea, M.D. Effectiveness of a Smartphone App (e-12HR) in Improving Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish University Students by Age, Gender, Field of Study, and Body Mass Index: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjar, L.M.; Mesa-Rodríguez, P.; García-Perea, M.D. Short-Term Effect of a Health Promotion Intervention Based on the Electronic 12-Hour Dietary Recall (e-12HR) Smartphone App on Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Spanish Primary Care Professionals: Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e49302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.T.; Ballart, J.F.; Pastor, G.C.; Jordà, E.B.; Val, V.A. Validación de un cuestionario de frecuencia de consumo alimentario corto: Reproducibilidad y validez [Validation of a short questionnaire on frequency of dietary intake: Reproducibility and validity]. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 23, 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W. Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, N.; Giabbanelli, P. Accurately inferring compliance to five major food guidelines through simplified surveys: Applying data mining to the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018, 4, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, K.L.; Smith, C.E.; Lai, C.; Ordovas, J.M. Quantifying diet for nutrigenomic studies. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 33, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. Principles of Nutritional Assessment, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Solera, A.; Gamero, A. Healthy habits in university students of health sciences and other branches of knowledge: A comparative study. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet 2019, 23, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Prevalencia y relación entre el nivel de actividad física y las actitudes alimenticias anómalas en estudiantes universitarias españolas de ciencias de la salud y la educación [Prevalence and relationship between physical activity and abnormal eating attitudes in Spanish women university students in Health and Education Sciences]. Rev. Esp. Salud. Publica 2011, 85, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, N.; Achkar, A.; Abdallah, A.; Rizk, S. Eating habits and obesity among Lebanese university students. Nutr. J. 2008, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yolcuoğlu, I.Z.; Kızıltan, G. Effect of Nutrition Education on Diet Quality, Sustainable Nutrition and Eating Behaviors among University Students. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2022, 41, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, H.; Fallaize, R.; Gallagher, C.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Woolhead, C.; Walsh, M.C.; Macready, A.L.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Mathers, J.C.; Gibney, M.J.; et al. Online dietary intake estimation: The Food4Me food frequency questionnaire. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutishauser, I.H. Dietary intake measurements. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Moreno, J.M.; Gorgojo, L. Valoración de la ingesta dietética a nivel poblacional mediante cuestionarios individuales: Sombras y luces metodológicas [Assessment of dietary intake at the population level through individual questionnaires: Methodological shadows and lights]. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2007, 81, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurandhar, N.V.; Schoeller, D.; Brown, A.W.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Thomas, D.; Sørensen, T.I.; Speakman, J.R.; Jeansonne, M.; Allison, D.B. Energy balance measurement: When something is not better than nothing. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1175–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food Group | Recommendation | Score (Form with Dietary Information and e-12HR) |

|---|---|---|

| Scoring of Food Groups Calculated on a daily basis | ||

| Fruits | ≥3 serving/day | 3 |

| Vegetables | ≥3 serving/day | 3 |

| Cereals | 3–6 serving/day | 3 |

| Olive oil | 3–4 serving/day | 3 |

| Milk and dairy products | 2–3 serving/day | 2 |

| Fermented beverages | 1–2 serving/day | 1 |

| Scoring of food groups calculated on a weekly basis | ||

| Nuts | 3–7 serving/week | 2 |

| Potatoes | ≤3 serving/week | 1 |

| Legumes | ≥2 serving/week | 1 |

| Eggs | 3–4 serving/week | 1 |

| Fish | ≥2 serving/week | 1 |

| White meat | 2–3 serving/week | 1 |

| Red and processed meat | ≤2 serving/week | 1 |

| Sweets | ≤2 serving/week | 1 |

| Total maximum score | 24 | |

| Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants who completed the study | 139 (100) | - * | - |

| Gender | - | - | |

| Females | 111 (79.9) | - | - |

| Males | 28 (20.1) | - | - |

| Age (Years) | 21.3 (4.5) | 19.9 (2.7) | |

| <20 | 70 (50.4) | - | - |

| ≥20 | 69 (49.6) | - | - |

| Studies | - | - | |

| Pharmacy | 89 (64.0) | - | - |

| Dentistry | 50 (36.0) | - | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.2 (3.7) | 21.5 (3.7) | |

| <25 | 118 (84.9) | - | - |

| ≥25 | 21 (15.1) | - | - |

| Smoking Status | - | - | |

| No | 114 (82.0) | - | - |

| Yes | 25 (18.0) | - | - |

| Physical activity status (m/w) | - | - | |

| ≥150 | 93 (66.9) | - | - |

| <150 | 46 (33.1) | - | - |

| Form with Dietary Information | e12HR Application | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p-Value * | |

| All | 14.3 (3.4) | 14.0 (5.0) | 6.8 (2.7) | 7.0 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Females | 14.3 (3.4) | 15.0 (5.0) | 6.8 (2.8) | 7.0 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Males | 14.3 (3.4) | 14.0 (5.0) | 7.0 (2.1) | 7.0 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Form with Dietary Information | e12HR Application | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| High | Moderate | Low | High | Moderate | Low | p-Value * | |

| All | 69 (49.6) | 64 (46.0) | 6 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (23.7) | 106 (76.3) | <0.001 |

| Females | 56 (50.5) | 50 (45.0) | 5 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (24.3) | 84 (75.7) | <0.001 |

| Males | 13 (46.4) | 14 (50.0) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (21.4) | 22 (78.6) | <0.001 |

| MDSS Index (from e12HR Application) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

| All | |||

| Normal/underestimation | 2 (1.4) | 12.0 (1.4) | 12.0 (- *) |

| Overestimation | 137 (98.6) | 6.7 (2.6) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| Within overestimation category | |||

| Low | 41 (29.5) | 8.1 (2.8) | 8.0 (4.0) |

| Moderate | 67 (48.2) | 6.7 (2.2) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| High | 29 (20.9) | 4.9 (2.2) | 5.0 (3.0) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | |||

| Normal/underestimation | 1 (0.9) | 13.0 (-) | 13.0 (-) |

| Overestimation | 110 (99.1) | 6.7 (2.8) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| Within overestimation category | |||

| Low | 35 (31.5) | 8.2 (2.9) | 8.0 (4.0) |

| Moderate | 51 (45.9) | 6.7 (2.3) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| High | 24 (21.6) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| Male | |||

| Normal/underestimation | 1 (3.6) | 11.0 (-) | 11.0 (-) |

| Overestimation | 27 (96.4) | 6.8 (2.0) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| Within overestimation category | |||

| Low | 6 (21.4) | 7.7 (2.2) | 7.0 (4.0) |

| Moderate | 16 (57.1) | 6.6 (1.9) | 7.0 (3.0) |

| High | 5 (17.9) | 6.6 (2.3) | 7.0 (4.0) |

| MDSS Index (from e12HR Application) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category Mean (SD) | p-Value | |

| All | ||

| Normal/underestimation | Overestimation | 0.008 ** |

| 12.0 (1.4) | 6.7 (2.6) | |

| Multiple comparisons within overestimation category | ||

| Low overestimation 8.1 (2.8) | Moderate overestimation 6.7 (2.2) | 0.004 *** |

| Low overestimation 8.1 (2.8) | High overestimation 4.9 (2.2) | <0.001 *** |

| Moderate overestimation 6.7 (2.2) | High overestimation 4.9 (2.2) | <0.001 *** |

| Females | ||

| Normal/underestimation 13.0 (− *) | Overestimation 6.7 (2.8) | 0.018 ** |

| Multiple comparisons within overestimation category | ||

| Low overestimation 8.2 (2.9) | Moderate overestimation 6.7 (2.3) | 0.010 *** |

| Low overestimation 8.2 (2.9) | High overestimation 4.5 (2.1) | <0.001 *** |

| Moderate overestimation 6.7 (2.3) | High overestimation 4.5 (2.1) | <0.001 *** |

| Males | ||

| Normal/underestimation 11.0 (−) | Overestimation 6.8 (2.0) | 0.071 ** |

| Multiple comparisons within overestimation category | ||

| Low overestimation 7.7 (2.2) | Moderate overestimation 6.6 (1.9) | 0.260 *** |

| Low overestimation 7.7 (2.2) | High overestimation 6.6 (2.3) | 0.449 *** |

| Moderate overestimation 6.6 (1.9) | High overestimation 6.6 (2.3) | 0.486 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Béjar, L.M. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Association with Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior (Discrepancy between Self-Perceived and Actual Diet Quality): A Cross-Sectional Study among Spanish University Students of Both Genders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193364

Béjar LM. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Association with Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior (Discrepancy between Self-Perceived and Actual Diet Quality): A Cross-Sectional Study among Spanish University Students of Both Genders. Nutrients. 2024; 16(19):3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193364

Chicago/Turabian StyleBéjar, Luis M. 2024. "Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Association with Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior (Discrepancy between Self-Perceived and Actual Diet Quality): A Cross-Sectional Study among Spanish University Students of Both Genders" Nutrients 16, no. 19: 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193364

APA StyleBéjar, L. M. (2024). Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Association with Self-Perception of Dietary Behavior (Discrepancy between Self-Perceived and Actual Diet Quality): A Cross-Sectional Study among Spanish University Students of Both Genders. Nutrients, 16(19), 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193364