Lost in Transition: Insights from a Retrospective Chart Audit on Nutrition Care Practices for Older Australians with Malnutrition Transitioning from Hospital to Home

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

- (1)

- Admitted from home and discharged home to independent living in the community.

- (2)

- Admitted to acute medical or surgical wards.

- (3)

- Seen by a dietitian during admission.

- (4)

- Had a documented diagnosis of malnutrition by the dietitian in a chart entry for that admission.

- (1)

- Admitted to psychiatric or intensive care units.

- (2)

- Admitted for day surgery or day procedures.

- (3)

- Discharged home with ‘Hospital in the Home (HITH)’ or similar services.

- (4)

- If their place of residence subsequently changed to a residential aged care facility prior to discharge.

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Inpatient Nutrition Care

3.3. Post-Discharge Nutrition Care and Follow-Up

3.3.1. Nutrition-Focused Discharge Planning

3.3.2. Food First Approach after Hospital Discharge

3.3.3. Oral Nutrition Supplementation after Hospital Discharge

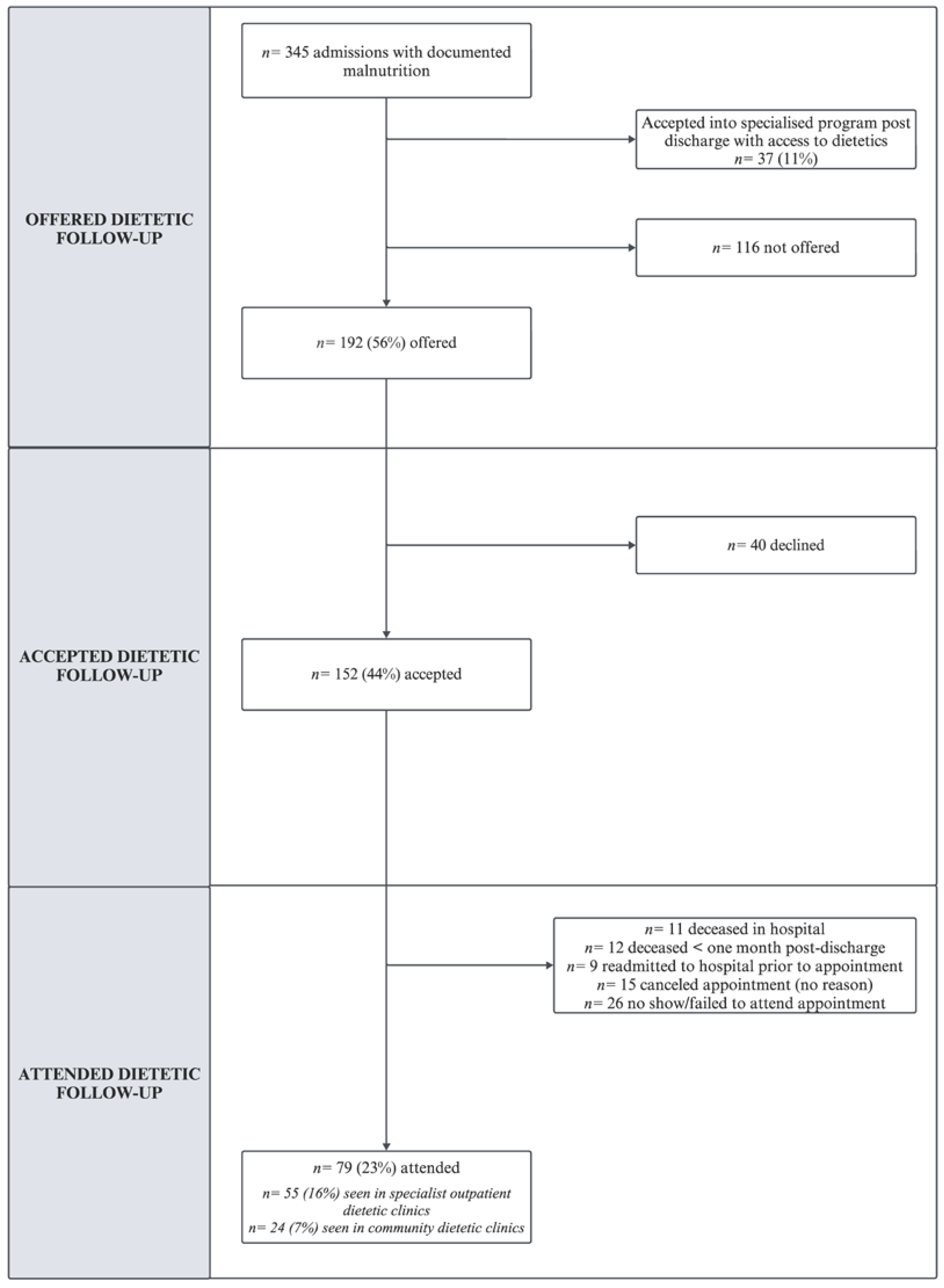

3.3.4. Dietetic Follow-Up after Hospital Discharge

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Data Variables Extracted from ieMR

| Domain | Data Variable |

|---|---|

| Admission details | URN |

| Admission date | |

| Ward location(s) | |

| Discharge date | |

| Discharge destination | |

| Patient demographics | Age |

| Gender | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Marital status/living arrangement | |

| Living arrangement | |

| Post code (ABS region) | |

| Nutrition screening and assessment | Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) score |

| Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) score |

| Domain | Data Variable |

|---|---|

| Inpatient nutrition care | Seen by dietitian assistant |

| Seen by dietitian (face-to-face, chart review, or both) | |

| Hospital diet code(s) | |

| Provision of ONS | |

| Provision of enteral or parenteral nutrition | |

| Other nutrition interventions (e.g., dietitian extras) | |

| Nutrition education provided (verbal, printed materials) | |

| Post-discharge nutrition care | Post-discharge nutrition care plan documented in ieMR |

| Referral to follow-up with community/outpatient dietitian | |

| Prescription (new or existing) for ONS post-discharge | |

| Recommendation to follow-up with GP | |

| Referral to community services (e.g., MOW or similar) | |

| Patient attendance at outpatient/community dietetics | |

| Patient deceased ≤ six months of discharge from the admission |

References

- Scholes, G. Protein-energy malnutrition in older Australians: A narrative review of the prevalence, causes and consequences of malnutrition, and strategies for prevention. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2022, 33, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Haß, U.; Pirlich, M. Malnutrition in older adults-recent advances and remaining challenges. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Wright, O.R.L.; Woo, J.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Malnutrition in older adults. Lancet 2023, 401, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Ageing and Health [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Agarwal, E.; Ferguson, M.; Banks, M.; Batterham, M.; Bauer, J.; Capra, S.; Isenring, E. Malnutrition and poor food intake are associated with prolonged hospital stay, frequent readmissions, and greater in-hospital mortality: Results from the Nutrition Care Day Survey 2010. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Ong, K.C.; Chan, Y.H.; Loke, W.C.; Ferguson, M.; Daniels, L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abizanda, P.; Sinclair, A.; Barcons, N.; Lizán, L.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Costs of malnutrition in institutionalized and community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanti, F.; Lo Buglio, A.; Quiete, S.; Vendemiale, G. Malnutrition in hospitalized old patients: Screening and diagnosis, clinical outcomes, and management. Nutrients 2022, 14, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, R.J.; King, C.L.; Stroud, M.A.; Jackson, A.A.; Elia, M. ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ predicts mortality and length of hospital stay in acutely ill elderly. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwee, K.; Clays, E.; Bocquaert, I.; Gobert, M.; Folens, B.; Defloor, T. Malnutrition and associated factors in elderly hospital patients: A Belgian cross-sectional, multi-centre study. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsitto, G.; Fulvio, F.; Tria, D.; Turi, V.; Venezia, A.; Manca, C. Nutritional status in hospitalized elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.I.T.D.; Perman, M.I.; Waitzberg, D.L. Hospital malnutrition in Latin America: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inciong, J.F.B.; Chaudhary, A.; Hsu, H.-S.; Joshi, R.; Seo, J.-M.; Trung, L.V.; Ungpinitpong, W.; Usman, N. Hospital malnutrition in northeast and southeast Asia: A systematic literature review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 39, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, K.E.; Batterham, M.J.; Bowden, S.; Ghosh, A.; Caldwell, K.; Barone, L.; Mason, M.; Potter, J.; Meyer, B.; Milosavljevic, M. A high prevalence of malnutrition in acute geriatric patients predicts adverse clinical outcomes and mortality within 12 months. E SPen Eur. E J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 8, e120–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van der Pols-Vijlbrief, R.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Visser, M. Perspectives on the causes of undernutrition of community-dwelling older adults: A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.; O’Neill, A.; O’Connor, M.; Ryan, D.; Tierney, A.; Galvin, R. The prevalence of malnutrition and impact on patient outcomes among older adults presenting at an Irish emergency department: A secondary analysis of the OPTI-MEND trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Collins, P.; Rattray, M. Identifying and managing malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia in the community: A narrative review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zügül, Y.; van Rossum, C.; Visser, M. Prevalence of undernutrition in community-dwelling older adults in the Netherlands: Application of the SNAQ65+ screening tool and GLIM consensus criteria. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streicher, M.; van Zwienen-Pot, J.; Bardon, L.; Nagel, G.; Teh, R.; Meisinger, C.; Colombo, M.; Torbahn, G.; Kiesswetter, E.; Flechtner-Mors, M.; et al. Determinants of incident malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults: A MaNuEL multicohort meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, M.; Paur, I.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Gjøra, L.; Skjellegrind, H.K.; Thingstad, P.; Strand, B.H.; Selbæk, G.; Fagerhaug, T.N.; Thoresen, L. Prevalence of malnutrition among older adults in a population-based study—The HUNT Study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 57, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leij-Halfwerk, S.; Verwijs, M.H.; van Houdt, S.; Borkent, J.W.; Guaitoli, P.R.; Pelgrim, T.; Heymans, M.W.; Power, L.; Visser, M.; Corish, C.A.; et al. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition risk in European older adults in community, residential and hospital settings, according to 22 malnutrition screening tools validated for use in adults ≥65 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2019, 126, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.M.; James, E.P. Barriers and facilitators to undertaking nutritional screening of patients: A systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russel, C. Addressing Malnutrition in Older Adults during Care Transition: Current State of Assessment. Available online: https://www.mealsonwheelsamerica.org/docs/default-source/research/nourishing-transitions/addressing-malnutrition-web-final.pdf?sfvrsn=f045ba3b_2 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Starr, K.N.; Porter McDonald, S.R.; Bales, C.W. Nutritional vulnerability in older adults: A continuum of concerns. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2015, 4, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Length of Hospital Stay [Internet]. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/length-of-hospital-stay.html?oecdcontrol-b84ba0ecd2-var3=2022 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Laur, C.; Curtis, L.; Dubin, J.; McNicholl, T.; Valaitis, R.; Douglas, P.; Bell, J.; Bernier, P.; Keller, H. Nutrition care after discharge from hospital: An exploratory analysis from the More-2-Eat study. Healthcare 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, M.; Vest, M.T.; Shapero, M.; Papas, M. Malnourished adults’ receipt of hospital discharge nutrition care instructions: A pilot study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaegi-Braun, N.; Kilchoer, F.; Dragusha, S.; Gressies, C.; Faessli, M.; Gomes, F.; Deutz, N.E.; Stanga, Z.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Nutritional support after hospital discharge improves long-term mortality in malnourished adult medical patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2431–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, T.; Tolstrup, U.; Beck, A.M.; Holst, M.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Hovhannisyan, K.; Thomsen, T. Individualised dietary counselling for nutritionally at-risk older patients following discharge from acute hospital to home: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, I.; Volkert, D.; de Groot, L.; Beck, A.M.; Feldblum, I.; Jobse, I.; Neelemaat, F.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Shahar, D.R.; Smeets, E.; et al. Effectiveness of nutritional interventions in older adults at risk of malnutrition across different health care settings: Pooled analyses of individual participant data from nine randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, N.M.L.; Belqaid, K.; Lugnet, K.; Nielsen, A.L.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Beck, A.M. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary nutritional support in older hospitalised patients: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 27, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Donnelly, R.; Laur, C.; Goharian, L.; Nasser, R. Consensus-based nutrition care pathways for hospital-to-community transitions and older adults in primary and community care. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2022, 46, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Slaughter, S.; Gramlich, L.; Namasivayam-MacDonald, A.; Bell, J.J. Multidisciplinary nutrition care: Benefitting patients with malnutrition across healthcare sectors. In Interdisciplinary Nutritional Management and Care for Older Adults: An Evidence-Based Practical Guide for Nurses; Geirsdóttir, Ó.G., Bell, J.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, H.; Payette, H.; Laporte, M.; Bernier, P.; Allard, J.; Duerksen, D.; Gramlich, L.; Jeejeebhoy, K. Patient-reported dietetic care post hospital for free-living patients: A Canadian Malnutrition Task Force study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Mudge, A.M.; Banks, M.D.; Rogers, L.; Allen, J.; Vogler, B.; Isenring, E. From hospital to home: Limited nutritional and functional recovery for older adults. J. Frailty Aging 2015, 4, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.M.; Mudge, A.M.; Banks, M.D.; Rogers, L.; Demedio, K.; Isenring, E. Improving nutritional discharge planning and follow up in older medical inpatients: Hospital to Home Outreach for Malnourished Elders (‘HHOME’). Nutr. Diet. 2018, 75, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Laporte, M.; Payette, H.; Allard, J.; Bernier, P.; Duerksen, D.; Gramlich, L.; Jeejeebhoy, K. Prevalence and predictors of weight change post discharge from hospital: A study of the Canadian Malnutrition Task Force. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.J.; Rushton, A.; Elmas, K.; Banks, M.D.; Barnes, R.; Young, A.M. Are Malnourished inpatients treated by dietitians active participants in their nutrition care? Findings of an exploratory study of patient-reported measures across nine Australian hospitals. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Graham, I.D. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Somerset, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Detsky, A.S.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Baker, J.P.; Johnston, N.; Whittaker, S.; Mendelson, R.A.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 1987, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Health. EDS and the Viewer. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/ (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Yam, C.H.K.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Leung, M.C.M.; Chan, F.W.K.; Wong, F.Y.Y.; Yeoh, E.-K. Barriers to effective discharge planning: A qualitative study investigating the perspectives of frontline healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoniewska, B.; Santana, M.J.; Groshaus, H.; Stajkovic, S.; Cowles, J.; Chakrovorty, D.; Ghali, W.A. Barriers to discharge in an acute care medical teaching unit: A qualitative analysis of health providers’ perceptions. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2015, 8, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimla, B.; Parkinson, L.; Wood, D.; Powell, Z. Hospital discharge planning: A systematic literature review on the support measures that social workers undertake to facilitate older patients’ transition from hospital admission back to the community. Australas. J. Ageing 2023, 42, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayajneh, A.A.; Hweidi, I.M.; Abu Dieh, M.W. Nurses’ knowledge, perception and practice toward discharge planning in acute care settings: A systematic review. Nursing Open 2020, 7, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukleja, A.; Gilbert, K.; Mogensen, K.M.; Walker, R.; Ward, C.T.; Ybarra, J. Standards for nutrition support: Adult hospitalized patients. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2018, 33, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watterson, C.; Fraser, A.; Banks, M.; Isenring, E.; Miller, M.; Silvester, C.; Hoevenaars, R.; Bauer, J.; Vivanti, A.; Ferguson, M. Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 66, S1–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Laur, C.; Atkins, M.; Bernier, P.; Butterworth, D.; Davidson, B.; Hotson, B.; Nasser, R.; Laporte, M.; Marcell, C.; et al. Update on the Integrated Nutrition Pathway for Acute Care (INPAC): Post implementation tailoring and toolkit to support practice improvements. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, H.; McCullough, J.; Davidson, B.; Vesnaver, E.; Laporte, M.; Gramlich, L.; Allard, J.; Bernier, P.; Duerksen, D.; Jeejeebhoy, K. The Integrated Nutrition Pathway for Acute Care (INPAC): Building consensus with a modified Delphi. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.J.; Young, A.M.; Hill, J.M.; Banks, M.D.; Comans, T.A.; Barnes, R.; Keller, H.H. Systematised, Interdisciplinary Malnutrition Program for impLementation and Evaluation delivers improved hospital nutrition care processes and patient reported experiences—An implementation study. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). ASPEN Adult Nutrition Care Pathway (Age 18+ Years) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.nutritioncare.org/uploadedFiles/Documents/Malnutrition/Adult-Nutrition-Pathway_9.14.22.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Wong, A.; Huang, Y.; Sowa, P.M.; Banks, M.D.; Bauer, J.D. Effectiveness of dietary counseling with or without nutrition supplementation in hospitalized patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2022, 46, 1502–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.; Baumgartner, A.; Bounoure, L.; Bally, M.; Deutz, N.E.; Greenwald, J.L.; Stanga, Z.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Association of nutritional support with clinical outcomes among medical inpatients who are malnourished or at nutritional risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1915138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, S.; Siddique, S.M.; McKeever, L.; Bloschichak, A.; D’Anci, K.; Leas, B.; Mull, N.K.; Tsou, A.Y. Malnutrition in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574798/ (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Nepal, S.; Keniston, A.; Indovina, K.A.; Frank, M.G.; Stella, S.A.; Quinzanos-Alonso, I.; McBeth, L.; Moore, S.L.; Burden, M. What do patients want? a qualitative analysis of patient, provider, and administrative perceptions and expectations about patients’ hospital stays. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1760–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkins, M.R.; Guenter, P.; DiMaria-Ghalili, R.A.; Jensen, G.L.; Malone, A.; Miller, S.; Patel, V.; Plogsted, S.; Resnick, H.E.; The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2014, 38, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestevik, C.H.; Molin, M.; Debesay, J.; Bergland, A.; Bye, A. Older patients’ and their family caregivers’ perceptions of food, meals and nutritional care in the transition between hospital and home care: A qualitative study. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, E.; Barone, L.; Mason, M.; Lambert, K.; McMahon, A. Patient-centred dietetic care from the perspectives of older malnourished patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B.; Weeks, L.; Steeves-Dorey, L.; McVeigh, W.; Stevens, S.; Moody, E.; Warner, G. Hospital to home: Supporting the transition from hospital to home for older adults. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 54, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebzeit, D.; Bratzke, L.; King, B. Strategies older adults use in their work to get back to normal following hospitalization. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdoway, A.; Page, F.; Bauer, J.; Dervan, N.; Maier, A.B. Individualised nutritional care for disease-related malnutrition: Improving outcomes by focusing on what matters to patients. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Admissions with Documented Malnutrition (n = 345) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 188 (54) |

| Female | 157 (46) | |

| Marital status | Married/Defacto | 167 (49) |

| Separated/Divorced/Never Married | 118 (34) | |

| Widowed | 53 (15) | |

| Not stated | 7 (2) | |

| Total admissions per patient | Patients with a single admission | 272 (89) a |

| Patients with two admissions | 29 (9) a | |

| Patients with three admissions | 5 (2) a | |

| Discharge destination | Home | 291 (84) |

| Died in hospital | 34 (10) | |

| Hospital transfer | 20 (6) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, K.; Bell, J.; Desbrow, B.; Roberts, S. Lost in Transition: Insights from a Retrospective Chart Audit on Nutrition Care Practices for Older Australians with Malnutrition Transitioning from Hospital to Home. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162796

Gomes K, Bell J, Desbrow B, Roberts S. Lost in Transition: Insights from a Retrospective Chart Audit on Nutrition Care Practices for Older Australians with Malnutrition Transitioning from Hospital to Home. Nutrients. 2024; 16(16):2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162796

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Kristin, Jack Bell, Ben Desbrow, and Shelley Roberts. 2024. "Lost in Transition: Insights from a Retrospective Chart Audit on Nutrition Care Practices for Older Australians with Malnutrition Transitioning from Hospital to Home" Nutrients 16, no. 16: 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162796

APA StyleGomes, K., Bell, J., Desbrow, B., & Roberts, S. (2024). Lost in Transition: Insights from a Retrospective Chart Audit on Nutrition Care Practices for Older Australians with Malnutrition Transitioning from Hospital to Home. Nutrients, 16(16), 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162796