Exploring the Role of Bergamot Polyphenols in Alleviating Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Tolerance through Modulation of Mitochondrial SIRT3

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Groups

2.3. Measurements of Thermal Pain Sensitivity after Morphine Injection

2.4. Superoxide Anion Detection

2.5. Nitrated Proteins Detection

2.6. Tissue Preparation for Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Extraction

2.7. Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analyses

2.8. Simple Western™ (WES)

2.9. Malondialdehyde Detection

2.10. MnSOD Activity

2.11. SIRT3 Deacetylase Activity Assay

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intraperitoneal Administration of Antioxidant Prevents Morphine-Induced Tolerance

3.2. The Development of Morphine-Induced Tolerance Is Associated with the Superoxide Formation: Inhibition by BPF

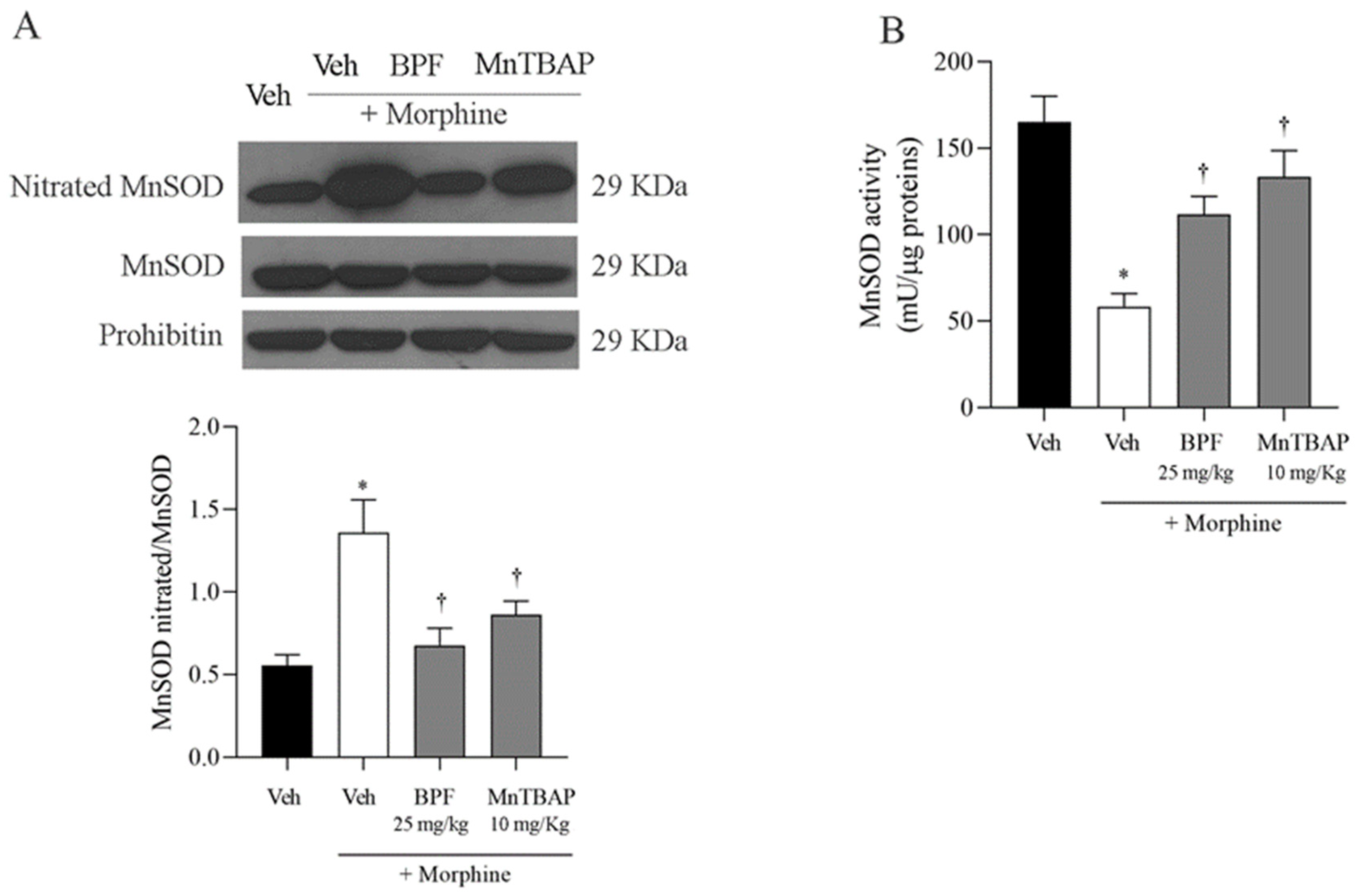

3.3. Inhibition of the Development of Morphine-Induced Tolerance with BPF Blocks Nitration and Enzymatic Inactivation of MnSOD, GS and GLT-1

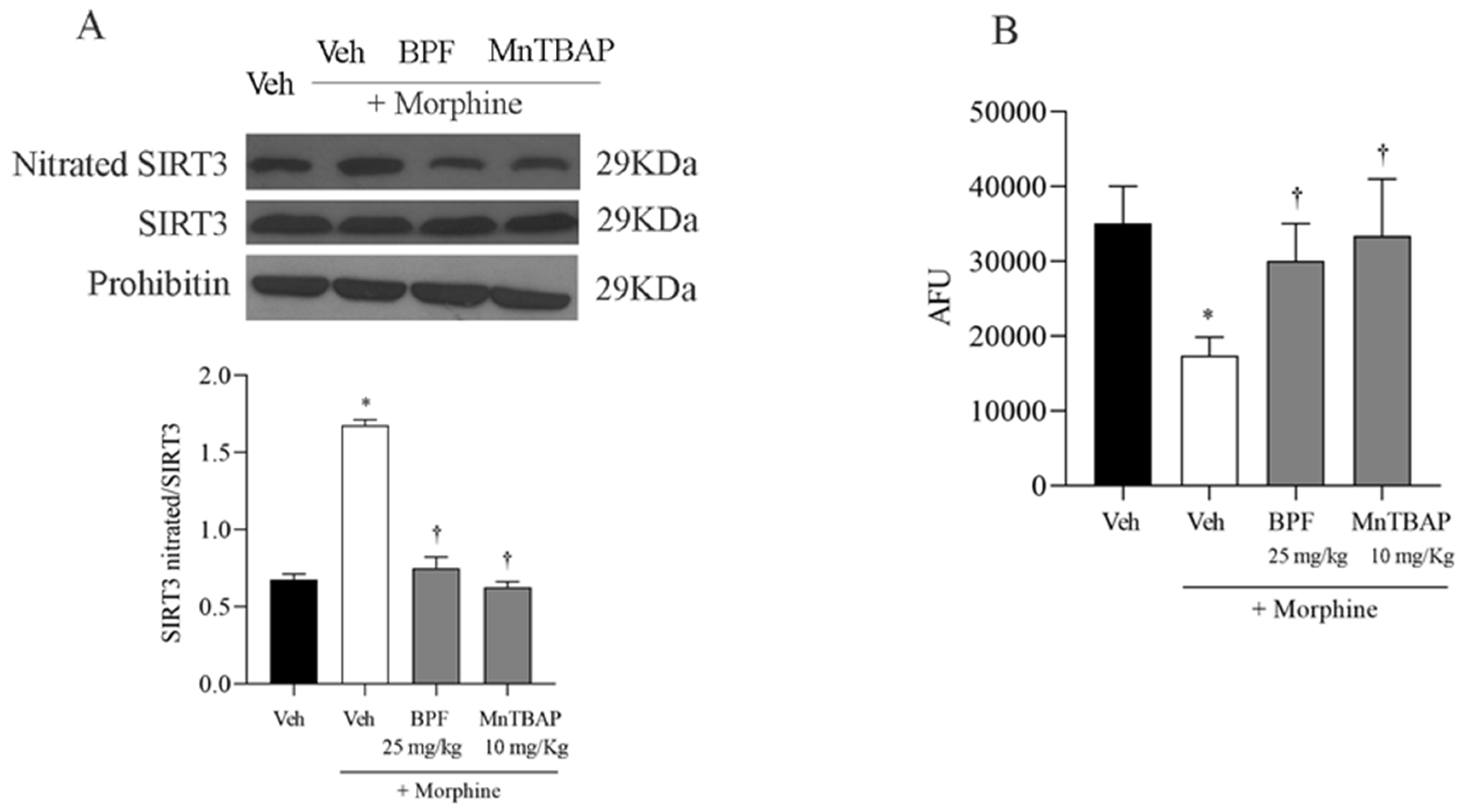

3.4. The Development of Morphine-Induced Tolerance Is Associated with SIRT3 Nitration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yong, R.J.; Mullins, P.M.; Bhattacharyya, N. Prevalence of Chronic Pain among Adults in the United States. Pain 2022, 163, e328–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.A.; Hotham, E.; Hall, C.; Williams, M.; Suppiah, V. Pharmacogenomics and Patient Treatment Parameters to Opioid Treatment in Chronic Pain: A Focus on Morphine, Oxycodone, Tramadol, and Fentanyl. Pain Med. 2017, 18, 2369–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Calderon, J.; García-Muñoz, C.; Rufo-Barbero, C.; Matias-Soto, J.; Cano-García, F.J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: An Overview of Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Pain 2024, 25, 595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkinshaw, H.; Friedrich, C.M.; Cole, P.; Eccleston, C.; Serfaty, M.; Stewart, G.; White, S.; Moore, R.A.; Phillippo, D.; Pincus, T. Antidepressants for pain management in adults with chronic pain: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 5, CD014682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzani, E.; Fanelli, A.; Malafoglia, V.; Tenti, M.; Ilari, S.; Corraro, A.; Muscoli, C.; Raffaeli, W. A Review of the Clinical and Therapeutic Implications of Neuropathic Pain. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilari, S.; Passacatini, L.C.; Malafoglia, V.; Oppedisano, F.; Maiuolo, J.; Gliozzi, M.; Palma, E.; Tomino, C.; Fini, M.; Raffaeli, W.; et al. Tantali Fibromyalgic Supplicium: Is There Any Relief with the Antidepressant Employment? A Systematic Review. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 186, 106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger, M.; Perrault, T.; Pessiot-Royer, S.; Parot-Schinkel, E.; Costerousse, F.; Rineau, E.; Lasocki, S. Opioid-Free Anesthesia Protocol on the Early Quality of Recovery after Major Surgery (SOFA Trial): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2024, 140, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauro, F.; Giancotti, L.A.; Ilari, S.; Dagostino, C.; Gliozzi, M.; Morabito, C.; Malafoglia, V.; Raffaeli, W.; Muraca, M.; Goffredo, B.M.; et al. Inhibition of Spinal Oxidative Stress by Bergamot Polyphenolic Fraction Attenuates the Development of Morphine Induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia in Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Fan, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ye, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M. Exercise Reduces Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Antinociceptive Tolerance. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6667474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Lu, Z.; Peng, J.; Li, X.-P.; Lan, L.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y. PAG Neuronal NMDARs Activation Mediated Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia by HMGB1-TLR4 Dependent Microglial Inflammation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 164, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilari, S.; Dagostino, C.; Malafoglia, V.; Lauro, F.; Giancotti, L.A.; Spila, A.; Proietti, S.; Ventrice, D.; Rizzo, M.; Gliozzi, M.; et al. Protective Effect of Antioxidants in Nitric Oxide/COX-2 Interaction during Inflammatory Pain: The Role of Nitration. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilari, S.; Lauro, F.; Giancotti, L.A.; Malafoglia, V.; Dagostino, C.; Gliozzi, M.; Condemi, A.; Maiuolo, J.; Oppedisano, F.; Palma, E.; et al. The Protective Effect of Bergamot Polyphenolic Fraction (BPF) on Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscoli, C.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Ndengele, M.M.; Mollace, V.; Porreca, F.; Fabrizi, F.; Esposito, E.; Masini, E.; Matuschak, G.M.; Salvemini, D. Therapeutic Manipulation of Peroxynitrite Attenuates the Development of Opiate-Induced Antinociceptive Tolerance in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3530–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Disorders—A Step towards Mitochondria Based Therapeutic Strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Makarczyk, M.J.; Lin, H. Role of Mitochondria in Mediating Chondrocyte Response to Mechanical Stimuli. Life Sci. 2020, 263, 118602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemmensen, M.M.; Borrowman, S.H.; Pearce, C.; Pyles, B.; Chandra, B. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ježek, J.; Cooper, K.F.; Strich, R. Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitochondrial Dynamics: The Yin and Yang of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cancer Progression. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faienza, F.; Rasola, A.; Filomeni, G. Nitric Oxide-Based Regulation of Metabolism: Hints from TRAP1 and SIRT3 Crosstalk. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 942729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, S.N.; Seelig, S.; Paul, S.; Poddar, R. Homocysteine-induced sustained GluN2A NMDA receptor stimulation leads to mitochondrial ROS generation and neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Tzeng, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wang, J.-D.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chen, W.-Y.; Kuan, Y.-H.; Liao, S.-L.; Wang, W.-Y.; Chen, C.-J. NMDA Receptor Inhibitor MK801 Alleviated Pro-Inflammatory Polarization of BV-2 Microglia Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 955, 175927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Kim, H.K.; Mo Chung, J.; Chung, K. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Are Involved in Enhancement of NMDA-Receptor Phosphorylation in Animal Models of Pain. Pain 2007, 131, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, B.; Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y. NMDA Receptors Regulate Oxidative Damage in Keratinocytes during Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in HaCaT Cells and Male Rats. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryter, S.W.; Kim, H.P.; Hoetzel, A.; Park, J.W.; Nakahira, K.; Wang, X.; Choi, A.M.K. Mechanisms of Cell Death in Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 49–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat-Mesquida, M.; Ferrer, M.D.; Pons, A.; Sureda, A.; Capó, X. Effects of Chronic Hydrogen Peroxide Exposure on Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Genes, ROS Production and Lipid Peroxidation in HL60 Cells. Mitochondrion 2024, 76, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milkovic, L.; Zarkovic, N.; Marusic, Z.; Zarkovic, K.; Jaganjac, M. The 4-Hydroxynonenal-Protein Adducts and Their Biological Relevance: Are Some Proteins Preferred Targets? Antioxidants 2023, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Bader Lange, M.L.; Sultana, R. Involvements of the Lipid Peroxidation Product, HNE, in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z. ROS-Induced Lipid Peroxidation Modulates Cell Death Outcome: Mechanisms behind Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, H.; Finocchietto, P.V.; Alippe, Y.; Rebagliati, I.; Elguero, M.E.; Villalba, N.; Poderoso, J.J.; Carreras, M.C. p66Shc Inactivation Modifies RNS Production, Regulates Sirt3 Activity, and Improves Mitochondrial Homeostasis, Delaying the Aging Process in Mouse Brain. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8561892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilari, S.; Giancotti, L.A.; Lauro, F.; Gliozzi, M.; Malafoglia, V.; Palma, E.; Tafani, M.; Russo, M.A.; Tomino, C.; Fini, M.; et al. Natural Antioxidant Control of Neuropathic Pain-Exploring the Role of Mitochondrial SIRT3 Pathway. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilari, S.; Giancotti, L.A.; Lauro, F.; Dagostino, C.; Gliozzi, M.; Malafoglia, V.; Sansone, L.; Palma, E.; Tafani, M.; Russo, M.A.; et al. Antioxidant Modulation of Sirtuin 3 during Acute Inflammatory Pain: The ROS Control. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalous, K.S.; Wynia-Smith, S.L.; Smith, B.C. Sirtuin Oxidative Post-Translational Modifications. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 763417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.-J.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-H.; Yu, X.-F.; Lv, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wei, Y.-F.; et al. The Sirtuin Family in Health and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, L.; Xu, K.; Chen, Z.; Ran, J.; Wu, L. The Role of SIRT3-Mediated Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Osteoarthritis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 3729–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; He, R.-R.; Liu, B. Mitochondrial Sirtuin 3: New Emerging Biological Function and Therapeutic Target. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8315–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, Y.; Kaundal, R.K. Role of SIRT3 in Mitochondrial Biology and Its Therapeutic Implications in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertuani, S.; Angusti, A.; Manfredini, S. The Antioxidants and Pro-Antioxidants Network: An Overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, J.C.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Nutraceuticals: Facts and Fiction. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2986–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Manach, C.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Dietary Polyphenols and the Prevention of Diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustyniak, A.; Bartosz, G.; Cipak, A.; Duburs, G.; Horáková, L.; Luczaj, W.; Majekova, M.; Odysseos, A.D.; Rackova, L.; Skrzydlewska, E.; et al. Natural and Synthetic Antioxidants: An Updated Overview. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 1216–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollace, V.; Sacco, I.; Janda, E.; Malara, C.; Ventrice, D.; Colica, C.; Visalli, V.; Muscoli, S.; Ragusa, S.; Muscoli, C.; et al. Hypolipemic and Hypoglycaemic Activity of Bergamot Polyphenols: From Animal Models to Human Studies. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Cherubim, D.J.; Buzanello Martins, C.V.; Oliveira Fariña, L.; da Silva de Lucca, R.A. Polyphenols as Natural Antioxidants in Cosmetics Applications. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Wu, C.-F. Anxiolytic Effect of Saponins from Panax Quinquefolium in Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilari, S.; Proietti, S.; Russo, P.; Malafoglia, V.; Gliozzi, M.; Maiuolo, J.; Oppedisano, F.; Palma, E.; Tomino, C.; Fini, M.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Role of Nutraceuticals in the Management of Neuropathic Pain in In Vivo Studies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoli, C.; Dagostino, C.; Ilari, S.; Lauro, F.; Gliozzi, M.; Bardhi, E.; Palma, E.; Mollace, V.; Salvemini, D. Posttranslational Nitration of Tyrosine Residues Modulates Glutamate Transmission and Contributes to N-Methyl-D-Aspartate-Mediated Thermal Hyperalgesia. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 950947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guerrero, F.; Lambrechts, K.; Mazur, A.; Buzzacott, P.; Belhomme, M.; Theron, M. Simulated air dives induce superoxide, nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and Ca2+ alterations in endothelial cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 76, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollace, V.; Muscoli, C.; Dagostino, C.; Giancotti, L.A.; Gliozzi, M.; Sacco, I.; Visalli, V.; Gratteri, S.; Palma, E.; Malara, N.; et al. The Effect of Peroxynitrite Decomposition Catalyst MnTBAP on Aldehyde Dehydrogenase-2 Nitration by Organic Nitrates: Role in Nitrate Tolerance. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 89, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, V.; Gliozzi, M.; Bombardelli, E.; Nucera, S.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Mollace, R.; Paone, S.; Bosco, F.; Scarano, F.; et al. The Synergistic Effect of Citrus bergamia and Cynara cardunculus Extracts on Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 10, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Harris, R.; Joel, S.P.; McDonald, P.; Currow, D.; Slevin, M.L. The Pharmacokinetics of Morphine and Morphine Glucuronide Metabolites after Subcutaneous Bolus Injection and Subcutaneous Infusion of Morphine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 49, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shoyaib, A.; Archie, S.R.; Karamyan, V.T. Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should It Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies? Pharm. Res. 2019, 37, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeirsch, H.; Meert, T.F. Morphine-Induced Analgesia in the Hot-Plate Test: Comparison between NMRI(Nu/Nu) and NMRI Mice. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004, 94, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, T.M.; Largent-Milnes, T.M.; Chen, Z.; Staikopoulos, V.; Esposito, E.; Dalgarno, R.; Fan, C.; Tosh, D.K.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Jacobson, K.A.; et al. Chronic Morphine-Induced Changes in Signaling at the A3 Adenosine Receptor Contribute to Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia, Tolerance, and Withdrawal. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 374, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, P.; Matthijssens, F.; Vanfleteren, J.R.; Braeckman, B.P. A simplified hydroethidine method for fast and accurate detection of superoxide production in isolated mitochondria. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 423, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalski, R.; Thiebaut, D.; Michałowski, B.; Ayhan, M.M.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Rostkowski, M.; Smulik-Izydorczyk, R.; Artelska, A.; Marcinek, A.; et al. Oxidation of ethidium-based probes by biological radicals: Mechanism, kinetics and implications for the detection of superoxide. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, T.M.; Janes, K.; Chen, Z.; Grace, P.M.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Largent-Milnes, T.M.; Neumann, W.L.; Watkins, L.R.; Spiegel, S.; et al. Activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor subtype 1 in the central nervous system contributes to morphine-induced hyperalgesia and antinociceptive tolerance in rodents. Pain 2020, 161, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, T.; Chen, Z.; Muscoli, C.; Bryant, L.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Dagostino, C.; Ryerse, J.; Rausaria, S.; Kamadulski, A.; et al. Targeting the Overproduction of Peroxynitrite for the Prevention and Reversal of Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6149–6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E. Can predictive biomarkers of chronic pain find in the immune system? Korean J. Pain 2018, 31, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruehl, S.; Milne, G.; Schildcrout, J.; Shi, Y.; Anderson, S.; Shinar, A.; Polkowski, G.; Mishra, P.; Billings, F.T. Oxidative Stress Is Associated with Characteristic Features of the Dysfunctional Chronic Pain Phenotype. Pain 2022, 163, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.; Bryant, L.; Muscoli, C.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Esposito, E.; Chen, Z.; Salvemini, D. Spinal NADPH Oxidase Is a Source of Superoxide in the Development of Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Antinociceptive Tolerance. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 483, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R. Nitric Oxide, Oxidants, and Protein Tyrosine Nitration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 4003–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvemini, D.; Little, J.W.; Doyle, T.; Neumann, W.L. Roles of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in Pain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, Y.-L.; Kao, C.-L.; Lin, S.-C.A.; Li, C.-J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Aging and Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, F.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Sakiyama, M.J.; Kayzuka, C.; Shukla, S.; Lacchini, R.; Cunniff, B.; Bonini, M.G. ROS Production by Mitochondria: Function or Dysfunction? Oncogene 2024, 43, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinić-Haberle, I.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Rebouças, J.S.; Ferrer-Sueta, G.; Mazzon, E.; Di Paola, R.; Radi, R.; Spasojević, I.; Benov, L.; Salvemini, D. Pure MnTBAP Selectively Scavenges Peroxynitrite over Superoxide: Comparison of Pure and Commercial MnTBAP Samples to MnTE-2-PyP in Two Models of Oxidative Stress Injury, an SOD-Specific Escherichia coli Model and Carrageenan-Induced Pleurisy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackovic, J.; Jeevakumar, V.; Burton, M.; Price, T.J.; Dussor, G. Peroxynitrite Contributes to Behavioral Responses, Increased Trigeminal Excitability, and Changes in Mitochondrial Function in a Preclinical Model of Migraine. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 1627–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.-K.; Lv, S.-J.; Wang, H.-P.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Gong, H.; Chen, X.-F.; Ren, S.-C.; et al. Sirtuin 2 Deficiency Aggravates Ageing-Induced Vascular Remodelling in Humans and Mice. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2746–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, A.S.; Strath, L.J.; Sorge, R.E. Dietary Interventions for Treatment of Chronic Pain: Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Pain Ther. 2020, 9, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Spadaccini, D.; Botteri, L.; Girometta, C.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Petrangolini, G.; Infantino, V.; Rondanelli, M. Efficacy of bergamot: From anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms to clinical applications as preventive agent for cardiovascular morbidity, skin diseases, and mood alterations. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, P.P.; Patti, A.M.; Nikolic, D.; Giglio, R.V.; Castellino, G.; Biancucci, T.; Geraci, F.; David, S.; Montalto, G.; Rizvi, A.; et al. Bergamot Reduces Plasma Lipids, Atherogenic Small Dense LDL, and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Subjects with Moderate Hypercholesterolemia: A 6 Months Prospective Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 6, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Pandolfo, G.; Crucitti, M.; Cacciola, M.; Santoro, V.; Spina, E.; Zoccali, R.A.; Muscatello, M.R.A. Low-Dose of Bergamot-Derived Polyphenolic Fraction (BPF) Did Not Improve Metabolic Parameters in Second Generation Antipsychotics-Treated Patients: Results from a 60-days Open-Label Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauman, M.C.; Johnson, J.J. Clinical application of bergamot (Citrus bergamia) for reducing high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease markers. Integr. Food Nutr. Metab. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, P.; Marchetti, M.; Frank, G.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Colica, C.; Cianci, R.; De Lorenzo, A.; Di Renzo, L. Antioxidant-Enriched Diet on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Gene Expression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Genes 2023, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vehicle Group | Morphine Group | BPF Group | MnTBAP Group | Acute Morphine Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment for 4 days | i.p. saline + s.c. saline | i.p saline + s.c. morphine (20 mg/kg) | i.p. BPF + s.c. morphine (20 mg/kg) | i.p. MnTBAP + s.c. morphine (20 mg/kg) | |

| Treatment on day 5 | i.p. saline + s.c. morphine (3 mg/kg) | i.p. saline + s.c. morphine (3 mg/kg) | i.p. BPF (5–50 mg/kg) + s.c. morphine (3 mg/kg) | i.p. MnTBAP (5–30 mg/kg) + s.c. morphine (3 mg/kg) | s.c. single dose of morphine (1, 3, 6 mg/kg) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilari, S.; Nucera, S.; Passacatini, L.C.; Scarano, F.; Macrì, R.; Caminiti, R.; Ruga, S.; Serra, M.; Giancotti, L.A.; Lauro, F.; et al. Exploring the Role of Bergamot Polyphenols in Alleviating Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Tolerance through Modulation of Mitochondrial SIRT3. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162620

Ilari S, Nucera S, Passacatini LC, Scarano F, Macrì R, Caminiti R, Ruga S, Serra M, Giancotti LA, Lauro F, et al. Exploring the Role of Bergamot Polyphenols in Alleviating Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Tolerance through Modulation of Mitochondrial SIRT3. Nutrients. 2024; 16(16):2620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162620

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlari, Sara, Saverio Nucera, Lucia Carmela Passacatini, Federica Scarano, Roberta Macrì, Rosamaria Caminiti, Stefano Ruga, Maria Serra, Luigino Antonio Giancotti, Filomena Lauro, and et al. 2024. "Exploring the Role of Bergamot Polyphenols in Alleviating Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Tolerance through Modulation of Mitochondrial SIRT3" Nutrients 16, no. 16: 2620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162620

APA StyleIlari, S., Nucera, S., Passacatini, L. C., Scarano, F., Macrì, R., Caminiti, R., Ruga, S., Serra, M., Giancotti, L. A., Lauro, F., Dagostino, C., Mazza, V., Ritorto, G., Oppedisano, F., Maiuolo, J., Palma, E., Malafoglia, V., Tomino, C., Mollace, V., & Muscoli, C. (2024). Exploring the Role of Bergamot Polyphenols in Alleviating Morphine-Induced Hyperalgesia and Tolerance through Modulation of Mitochondrial SIRT3. Nutrients, 16(16), 2620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162620