Construction and Content Validation of Mobile Devices’ Application Messages about Food and Nutrition for DM2 Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

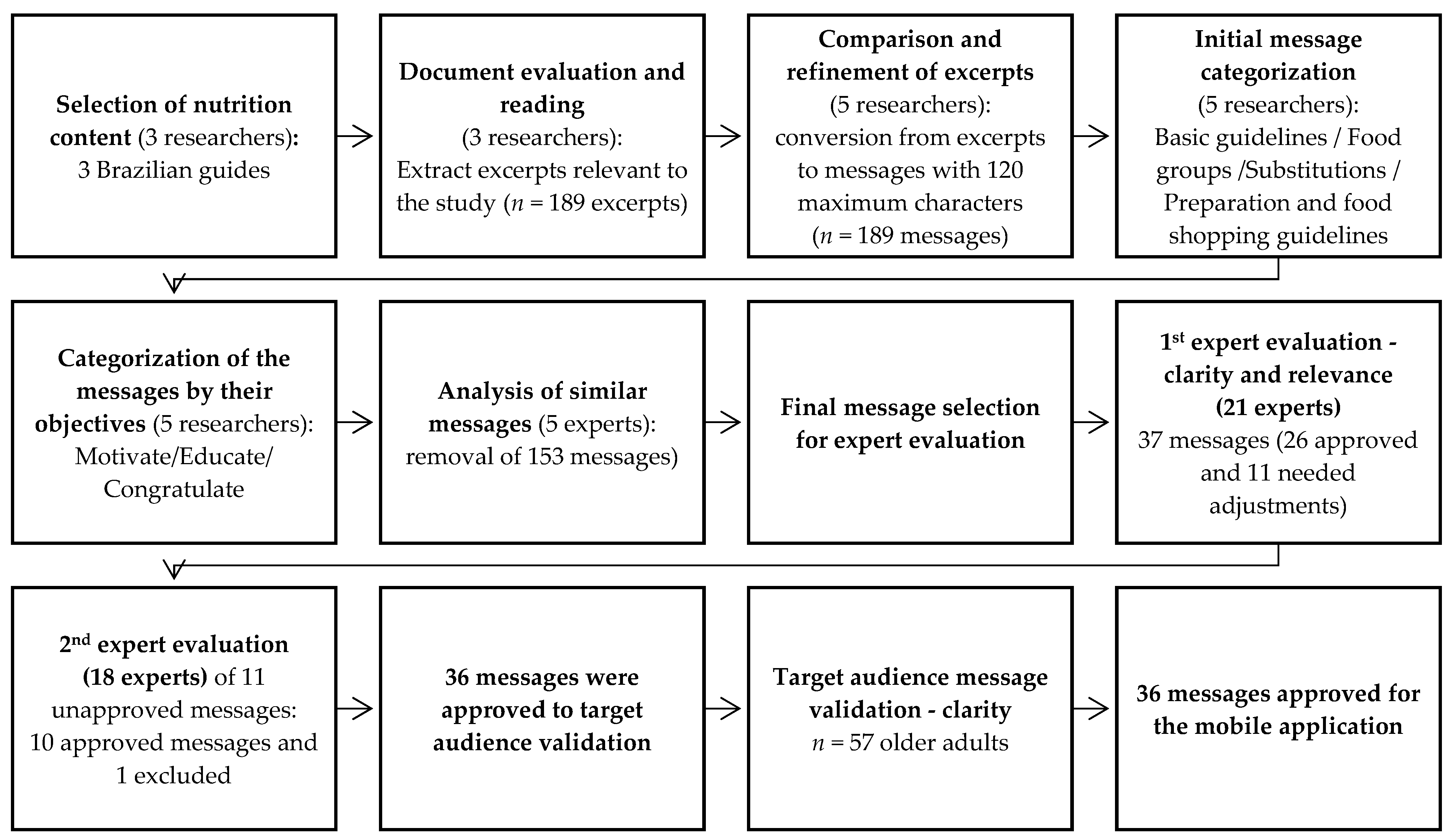

2.2. Message Construction

2.3. Experts’ Message Validation (Clarity and Relevance)

2.4. Target Audience Message Validation (Clarity)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Message Construction

3.2. Experts’ Message Validation (Clarity and Relevance)

3.3. Target Audience Message Validation (Clarity)

4. Discussion

4.1. Message Construction

4.2. Experts’ Message Validation (Clarity and Relevance)

4.3. Target Audience Message Validation (Clarity)

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística). Síntese de Indicadores Sociais: Uma Análise Das Condições de Vida Da Brasileira: 2022. In Coordenação de População e Indicadores Sociais; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022; Volume 49, p. 154. ISSN 1516-3296. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, L.T.V.; Albert, S.M. Aging in Brazil. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassis, A.; Fichot, M.C.; Horcajada, M.N.; Horstman, A.M.H.; Duncan, P.; Bergonzelli, G.; Preitner, N.; Zimmermann, D.; Bosco, N.; Vidal, K.; et al. Nutritional and Lifestyle Management of the Aging Journey: A Narrative Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1087505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Huelgas, R.; Gómez Peralta, F.; Rodríguez Mañas, L.; Formiga, F.; Puig Domingo, M.; Mediavilla Bravo, J.J.; Miranda, C.; Ena, J. Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Elderly Patients. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2018, 53, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliano, D.; Boyko, E. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th Edition Scientific Committee. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581934/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Francisco, P.M.S.B.; de Assumpção, D.; de Macedo Bacurau, A.G.; da Silva, D.S.M.; Yassuda, M.S.; Borim, F.S.A. Diabetes Mellitus in Older Adults, Prevalence and Incidence: Results of the FIBRA Study. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2022, 25, e210203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, R.C.P.; Duncan, B.B.; Malta, D.C.; Iser, B.P.M.; Schmidt, M.I. Evolution of Diabetes in Brazil: Prevalence Data from the 2013 and 2019 Brazilian National Health Survey. Cad. Saúde Pública 2022, 38, e00149321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, W.P.; de Freitas, F.B.D.; Soares, R.M.; de Andrade Souza, G.L.; de Sousa Campos, P.I.; de Oliveira Bezerra, C.M.; Ramos, K.S.; dos Santos Barbosa, L.D. Complicações Do Diabetes Mellitus Na População Idosa. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 33283–33292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Leite, E.; Lubenow, J.A.M.; Moreira, M.R.C.; Martins, M.M.; da Costa, I.P.; Silva, A.O. Avaliação Do Impacto Da Diabetes Mellitus Na Qualidade de Vida de Idosos. Ciênc. Cuid. Saúde 2014, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Almeida Costa, P.; de Oliveira Neta, M.S.; de Azevedo, T.F.; Cavalcanti, L.T.; de Sousa Rocha, S.R.; Nogueira, M.F. Emotional Distress and Adherence to Self-Care Activities in Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus. Rev. Rene 2022, 23, e72264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Campos, L.F.; Baptista, D.R.; Strufaldi, M.; Gomes, D.L.; Guimarães, D.B.; Souto, D.L.; Marques, M.; de Santana Sousa, S.S.; Lauria, M.; et al. Terapia Nutricional No Pré-Diabetes e No Diabetes Mellitus Tipo 2. Dir. Off. Soc. Bras. Diabetes 2022, 2, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker-Clarke, A.; Walasek, L.; Meyer, C. Psychosocial Factors Influencing the Eating Behaviours of Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 77, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifirad, G.; Najimi, A.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Azadbakht, L. Application of BASNEF Educational Model for Nutritional Education among Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Improving the Glycemic Control. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2011, 16, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hur, M.H. The Effects of Dietary Education Interventions on Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, L.S.; Wilson, S.; Bhatt, P.; Bryant, M.; Burnett, A.; Camarda, J.N.; Chakravarthy, V.; Chandrashekhar, C.; Chaudhury, N.; Cimini, C.; et al. Community-Based Interventions for Detection and Management of Diabetes and Hypertension in Underserved Communities: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation in Brazil, India, South Africa and the USA. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coube, M.; Nikoloski, Z.; Mrejen, M.; Mossialos, E.; Getúlio Vargas, F.; Paulo, S. Inequalities in Unmet Need for Health Care Services and Medications in Brazil: A Decomposition Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2023, 19, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenedesi Júnior, M.A.; Rodrigues, D.P.V.; Merege, M.C.; Schwarz, F.S.; Gomes, G.S.B.F.; de Almeida Vasconcelos, J.L.; do Nascimento Melo, J.L.; De Amorim, K.T.; da Silva, K.C.R.; de Almeida Araújo, M.A.; et al. The Challenges in Rebuilding a Quality Public Health in Brazil. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2024, 22, e3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.S.C.; Nunes, B.P.; Duro, S.M.S.; de Cássia Duarte Lima, R.; Facchini, L.A. Lack of Access and the Trajectory of Healthcare Use by Elderly Brazilians. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 2213–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; International Telecommunication Union. Be Healthy Be Mobile a Handbook on How to Implement MAgeing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9789241514125. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew-Maich, N.; Harris, L.; Ploeg, J.; Markle-Reid, M.; Valaitis, R.; Ibrahim, S.; Gafni, A.; Isaacs, S. Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Mobile Health Technologies for Managing Chronic Conditions in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, J.O.V.; Andrade, R.M.C.; de Oliveira, P.A.M.; Duarte, P.; Santos, I.S.; de Evangelista, A.L.P.; Theophilo, R.L.; de Andrade, L.O.M.; de Barreto, I.C.H.C. Mobile Applications for Elderly Healthcare: A Systematic Mapping. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, T. Brazil Facing Ageing Population Challenges. Lancet 2023, 402, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundury, K.K.; Hathur, B. Intervention through Short Messaging System (SMS) and Phone Call Alerts Reduced HbA1C Levels in ~47% Type-2 Diabetics–Results of a Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iancu, I.; Iancu, B. Designing Mobile Technology for Elderly. A Theoretical Overview. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.N.; Cheng, P.L.; Chang, P.L. Evaluate the Usability of the Mobile Instant Messaging Software in the Elderly. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 245, pp. 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.D.; Koch, S.B.; Williford, P.M.; Feldman, S.R.; Pearce, D.J. Web App-and Text Message-Based Patient Education in Mohs Micrographic Surgery-a Randomized Controlled Trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Du, M.; Hao, R.; Zheng, H.; Yan, C. The Role of Text Messaging Intervention in Inner Mongolia among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Ginani, V.C.; Gandolfi, L.; Pratesi, R.; de Medeiros Nóbrega, Y.K. Content Validation and Semantic Evaluation of a Check-List Elaborated for the Prevention of Gluten Cross-Contamination in Food Services. Nutrients 2017, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crestani, A.H.; de Moraes, A.B.; de Souza, A.P.R. Content Validation: Clarity/Relevance, Reliability and Internal Consistency of Enunciative Signs of Language Acquisition. Codas 2017, 29, e20160180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil, Alimentação Cardioprotetora: Manual de Orientações Para Os Profissionais de Saúde Da Atenção Básica, Ministério da Saúde. 2018. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/alimentacao_cardioprotetora.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Ministério da Saúde. Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; ISBN 9788561091699.

- Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Ministério Da Saúde Orientação Alimentar de Pessoas Adultas Com Diabetes Mellitus. In Protocolo de Uso Do Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira; Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2022; Volume 4, ISBN 978-65-5993-225-2. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehring, R.J. Classification of Nursing Diagnosis: Proceedings of the Tenth Conference of North American Nursing Diagnoses Association; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994; ISBN 13978-0397550111. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, R.P.; Moreira, R.P.; Fontenele, F.C.; de Aguiar, A.S.C.; Joventino, E.S.; de Carvalho, E.C. Criteria for selection of experts for validationstudies of nursing phenomena criterios de selección de expertos para estudios de validación de fenómenos de enfermería. In Revista da Rede de Enfermagem do Nordeste 2011; Universidade Federal do Ceará: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2011; Volume 12, ISSN 1517-3852. [Google Scholar]

- Presotto, M.; de Mello Rieder, C.R.; Olchik, M.R. Validation of Content and Reliability of the Protocol for the Evaluation of Acquired Speech Disorders in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease (PADAF). Codas 2019, 31, e20180230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijering, J.V.; Kampen, J.K.; Tobi, H. Quantifying the Development of Agreement among Experts in Delphi Studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D.S.; King, D.W.; King, L.A. Focus Groups in Psychological Assessment: Enhancing Content Validity by Consulting Members of the Target Population. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, E.H.; Burnett, S.M.; Johnson, M.A.; Park, S.; Fischer, J.G.; Johnson, T. Improvement in A1C Levels and Diabetes Self-Management Activities Following a Nutrition and Diabetes Education Program in Older Adults. J. Nutr. Elder. 2007, 26, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde (Ed.) Fascículo 2 Protocolos de Uso Do Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira Na Orientação Alimentar Da Idosa; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil; Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021; ISBN 9788533428812.

- Fernández-Gómez, E.; Martín-Salvador, A.; Luque-Vara, T.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; Navarro-Prado, S.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Content Validation through Expert Judgement of an Instrument on the Nutritional Knowledge, Beliefs, and Habits of Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, L.J.; Gilmartin, S.K.; Bryant, A.N. Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web. Res. High. Educ. 2003, 44, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.J.; Bowers, B.J. Internet Recruitment and E-Mail Interviews in Qualitative Studies. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, E.; Gordon, N.P. Prevalence and Factors Influencing Use of Internet and Electronic Health Resources by Middle-Aged and Older Adults in a US Health Plan Population: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e11451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallukka, T.; Pietiläinen, O.; Jäppinen, S.; Laaksonen, M.; Lahti, J.; Rahkonen, O. Factors Associated with Health Survey Response among Young Employees: A Register-Based Study Using Online, Mailed and Telephone Interview Data Collection Methods. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, N.K.; Williams, O.O.; Parashar, S. SMARTWOMANTM: Feasibility Assessment of a Smartphone App to Control Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Vulnerable Diabetic Women. Clin. Cardiol. 2019, 42, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Holds a master’s degree/PhD in the health field | 3 points |

| Holds a master’s degree with a dissertation on older adults with DM2/mHealth/primary healthcare | 2 points |

| Holds a PhD with a thesis in the area of older adults with DM2/mHealth/primary healthcare | 2 points |

| Has a published article on older adults with DM2/mHealth/primary healthcare | 2 points |

| Published articles on health education/validation studies | 1 point |

| Has a recent clinical practice of at least one year in primary healthcare | 2 points |

| Has training (specialization) in older adults with DM2/mHealth/primary healthcare | 2 points |

| Total | 14 points |

| Messages in Brazilian Portuguese | Messages in English * |

|---|---|

| Sua alimentação deve ser baseada em alimentos naturais, como: frutas, hortaliças (verduras e legumes), cereais integrais (arroz integral, aveia etc.) e leguminosas (feijão, grão-de-bico etc.). | Your diet should be based on natural foods, such as fruit, vegetables, whole grains (brown rice, oats, etc.), and legumes (beans, chickpeas, etc.). |

| O consumo de doces e bebidas açucaradas (refrigerantes, refrescos em pó, sucos com açúcar) pode levar ao aumento de peso e de açúcar e gordura no sangue. | The consumption of sweets and sugary drinks (soft drinks, powdered drinks, juices with sugar) can lead to weight gain and an increase in sugar and fat in the blood. |

| Nem todo alimento “diet”, “light” ou “fit” é indicado para pessoas com diabetes, pois pode conter alta quantidade de gordura, sal, açúcar ou adoçante. Leia os rótulos. | Not all “diet”, “light”, or “fit” foods are suitable for people with diabetes, as they may contain a high amount of fat, salt, sugar, or sweetener. Read the labels. |

| Consumir hortaliças (verduras e legumes), frutas, leguminosas (feijão, lentilha etc.), carnes, ovos e leite favorece o controle do açúcar no sangue e da fome. | Eating vegetables, fruit, legumes (beans, lentils, etc.), meat, eggs, and milk helps control blood sugar and hunger. |

| Consumir alimentos integrais como arroz, pão, macarrão, faz parte da alimentação saudável, especialmente, para pessoas com diabetes. | Eating whole-grain foods such as rice, bread, and pasta is part of a healthy diet, especially for people with diabetes. |

| Aves, peixes e ovos são ricos em proteínas e emvitaminas, além de serem bons substitutos para as carnes vermelhas. | Chicken, fish, and eggs are rich in protein and vitamins and good red meat substitutes. |

| Bebidas alcoólicas podem atrapalhar o controle do açúcar no sangue, favorecer o ganho de peso e o aumento da pressão arterial. | Alcoholic drinks can hinder blood sugar control, encourage weight gain, and increase blood pressure. |

| Evite alimentos industrializados como salsicha, salgadinhos de pacote e refrigerantes, pois não são bons para a Saúde. | Avoid industrialized foods such as sausage, packet snacks, and soft drinks, as they are not good for your health. |

| Nas refeições ou lanches, coma primeiro as saladas e frutas, elas ajudam você a ficar mais satisfeito e será melhor para sua saúde. | At mealtimes or snacks, eat salads and fruit first; they will help you feel more satisfied and will be better for your health. |

| Combinar o iogurte natural com frutas e aveia ou sementes (linhaça, gergelim etc.) é uma boa opção para um lanche saboroso e saudável. | Combining natural yogurt with fruit and oats or seeds (linseed, sesame, etc.) is a good option for a tasty and healthy snack. |

| Congelar alimentos feitos em casa (como arroz, feijões, carnes e vegetais) e consumir durante a semana ou mês, facilita bastante a organização da sua alimentação. | Freezing homemade food (such as rice, beans, meat, and vegetables) and consuming it during the week or month makes it much easier to organize your diet. |

| Distribuir as refeições ao longo do dia (café da manhã, lanche, almoço, jantar e ceia) ajuda a comer quantidades de alimentos suficientes, evitando a fome extrema. | Distributing your meals throughout the day (breakfast, snack, lunch, dinner, and supper) helps you eat enough food to avoid extreme hunger. |

| A compra semanal de frutas e hortaliças (legumes e verduras) da estação fará que você tenha sempre alimentos saudáveis e mais baratos. | Buying seasonal fruit and vegetables weekly will ensure that you always have healthy and cheaper food. |

| Você deve cuidar da sua alimentação para ter mais qualidade de vida. | You need to take care of your diet for a better quality of life. |

| Organize a sua alimentação. Cuide de você! | Organize your diet. Take care of yourself! |

| Quando você adota uma alimentação saudável, inspira outras pessoas! | When you eat healthily, you inspire others! |

| Para a sua família e amigos é muito importante que você esteja bem! Portanto, cuide de sua alimentação. | It is essential to your family and friends that you look good! So, take care of your diet. |

| Alimentos naturais são mais saudáveis. Portanto, descasque mais e desembale menos! | Natural food is healthier than industrialized food. So, peel more and unpack less! |

| Leve com você alimentos saudáveis e que sejam fáceis de transportar e consumir, como frutas ou castanhas sem sal. | Bring healthy foods that are easy to transport and eat, such as fruit or unsalted nuts. |

| É possível preparar em casa comidas saudáveis. O nosso aplicativo tem algumas receitas. Prepare e compartilhe com quem você ama. | You can prepare healthy food at home. Our app has some recipes. Prepare them and share them with your loved ones. |

| Toda refeição saudável é um passo que você dá para uma vida melhor. | Every healthy meal is a step towards a better life. |

| Sua saúde é a principal motivação para comer refeições saudáveis! Nunca deixe de se cuidar. | Your health is the main motivation for eating healthy meals! Never stop taking care of yourself. |

| Cuidar da alimentação é muito bom! Sinta orgulho de você por escolher refeições saudáveis! | Taking care of your diet feels good! Be proud of yourself for choosing healthy meals! |

| Utilize receitas fáceis e saudáveis para facilitar o planejamento de sua alimentação | Use easy and healthy recipes to make your meal planning easier. |

| Todo dia é dia de decidir ser saudável. Parabéns pelo seu trabalho até aqui! | Every day is a day to decide to be healthy. Congratulations on your work so far! |

| Nesse período, você aprendeu muitas coisas sobre alimentação. Será cada vez mais fácil para você controlar o açúcar no sangue. | During this time, you have learned a lot about food. It will become easier and easier for you to control your blood sugar. |

| Conquistar uma alimentação equilibrada te ajuda a se sentir melhor em relação ao corpo e à saúde. Você também pode ser parte disso! | A balanced diet helps you feel better about your body and health. You can be part of it too! |

| Quando decidir consumir sobremesa, prefira frutas. | When you decide to have dessert, go for fruit. |

| Você pode substituir a linguiça, a mortadela e a salsicha por carne de boi, porco, frango, peixe ou queijos e ovo. | You can substitute beef, pork, chicken, fish, cheese, and eggs for sausages, bologna, and sausages. |

| Ter uma alimentação saudável pode ser desafiador, mas é um processo. Cada passo tornará esse caminho mais fácil! | Eating healthy can be challenging, but it is a process. Each step will make it easier! |

| Substitua os temperos industrializados prontos (tablete ou pó) pelos naturais, como: alho, cebola, alecrim, cebolinha, coentro, salsa, manjericão e limão. | Replace ready-made industrialized spices (tablets or powder) with natural ones, such as garlic, onion, rosemary, chives, coriander, parsley, basil, and lemon. |

| Comer sem pressa, com atenção e de forma saudável ajuda na digestão e no consumo adequado dos alimentos. | Eating without haste, with attention, and in a healthy way helps digestion and proper food consumption. |

| As frutas podem ser consumidas frescas, cozidas, assadas ou secas (desidratadas). Você pode comer a fruta pura em lanches ou incluir em saladas e sobremesas | Fruit can be eaten fresh, cooked, baked, or dried (dehydrated). You can eat fruit as a snack or include it in salads and desserts. |

| Fazer compras sem estar com fome favorece a compra de alimentos mais saudáveis e ajuda a economizar | Shopping when you are not hungry helps you buy healthier foods and save money. |

| Evite molhos prontos para saladas. Prefira opções mais saudáveis, como azeite, limão e vinagres ou molhos caseiros a base de iogurte natural | Avoid ready-made salad dressings. Prefer healthier options such as olive oil, lemon, vinegar, or homemade sauces based on natural yogurt. |

| Obrigada por aceitar participar desse programa! Você é essencial para que possamos ajudar outras pessoas. | Thank you for agreeing to take part in this program! You are essential for us to be able to help other people. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dusi, R.; Trombini, R.R.d.S.L.; Pereira, A.L.M.; Funghetto, S.S.; Ginani, V.C.; Stival, M.M.; Nakano, E.Y.; Zandonadi, R.P. Construction and Content Validation of Mobile Devices’ Application Messages about Food and Nutrition for DM2 Older Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142306

Dusi R, Trombini RRdSL, Pereira ALM, Funghetto SS, Ginani VC, Stival MM, Nakano EY, Zandonadi RP. Construction and Content Validation of Mobile Devices’ Application Messages about Food and Nutrition for DM2 Older Adults. Nutrients. 2024; 16(14):2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142306

Chicago/Turabian StyleDusi, Rafaella, Raiza Rana de Souza Lima Trombini, Alayne Larissa Martins Pereira, Silvana Schwerz Funghetto, Verônica Cortez Ginani, Marina Morato Stival, Eduardo Yoshio Nakano, and Renata Puppin Zandonadi. 2024. "Construction and Content Validation of Mobile Devices’ Application Messages about Food and Nutrition for DM2 Older Adults" Nutrients 16, no. 14: 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142306

APA StyleDusi, R., Trombini, R. R. d. S. L., Pereira, A. L. M., Funghetto, S. S., Ginani, V. C., Stival, M. M., Nakano, E. Y., & Zandonadi, R. P. (2024). Construction and Content Validation of Mobile Devices’ Application Messages about Food and Nutrition for DM2 Older Adults. Nutrients, 16(14), 2306. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142306