Potential Celiac Disease in Children: Health Status on A Long-Term Gluten-Containing Diet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Whole Cohort

3.2. Subgroup Analysis: Excluding Patients That Permanently Stopped Producing Antibodies during Follow-Up and Excluding Patients with a Follow-Up < 3 Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandile, R.; Auricchio, R.; Discepolo, V.; Troncone, R. Chapter 10—Potential celiac disease. In Pediatric and Adult Celiac Disease; Corazza, G.R., Troncone, R., Lenti, M.V., Silano, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Caio, G.; Giancola, F.; Rhoden, K.J.; Ruggeri, E.; Boschetti, E.; Stanghellini, V.; De Giorgio, R. Features and Progression of Potential Celiac Disease in Adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 686–693.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, F.; Trotta, L.; Alfano, C.; Balduzzi, D.; Staffieri, V.; Bianchi, P.I.; Marchese, A.; Vattiato, C.; Zilli, A.; Luinetti, O.; et al. Prevalence and natural history of potential celiac disease in adult patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, M.; Greenaway, E.A.; Holland, W.J.; Raju, S.A.; Rej, A.; Sanders, D.S. What are the clinical consequences of ‘potential’ coeliac disease? Dig. Liver Dis. Off J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2023, 55, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurppa, K.; Collin, P.; Sievänen, H.; Huhtala, H.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K. Gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life and bone mineral density in mild enteropathic coeliac disease: A prospective clinical trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repo, M.; Lindfors, K.; Mäki, M.; Huhtala, H.; Laurila, K.; Lähdeaho, M.L.; Saavalainen, P.; Kaukinen, K.; Kurppa, K. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Children With Potential Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosco, A.; Salvati, V.M.; Auricchio, R.; Maglio, M.; Borrelli, M.; Coruzzo, A.; Paparo, F.; Boffardi, M.; Esposito, A.; D’Adamo, G.; et al. Natural history of potential celiac disease in children. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 320–325, quiz e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auricchio, R.; Tosco, A.; Piccolo, E.; Galatola, M.; Izzo, V.; Maglio, M.; Paparo, F.; Troncone, R.; Greco, L. Potential celiac children: 9-year follow-up on a gluten-containing diet. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auricchio, R.; Mandile, R.; Del Vecchio, M.R.; Scapaticci, S.; Galatola, M.; Maglio, M.; Discepolo, V.; Miele, E.; Cielo, D.; Troncone, R.; et al. Progression of Celiac Disease in Children With Antibodies Against Tissue Transglutaminase and Normal Duodenal Architecture. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 413–420.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, E.; Castellaneta, S.; Francavilla, R.; Pulvirenti, A.; Naspi Catassi, G.; Catassi, C. SIGENP Working Group of Weaning and CD Risk. Long-Term Outcome of Potential Celiac Disease in Genetically at-Risk Children: The Prospective CELIPREV Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäki, M. Celiac disease treatment: Gluten-free diet and beyond. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 59 (Suppl. S1), S15–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurppa, K.; Paavola, A.; Collin, P.; Sievänen, H.; Laurila, K.; Huhtala, H.; Saavalainen, P.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K. Benefits of a gluten-free diet for asymptomatic patients with serologic markers of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 610–617.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Sampedro, A.; Olenick, M.; Maltseva, T.; Flowers, M. A Gluten-Free Diet, Not an Appropriate Choice without a Medical Diagnosis. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 2438934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandile, R.; Discepolo, V.; Scapaticci, S.; Del Vecchio, M.R.; Maglio, M.A.; Greco, L.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R. The Effect of Gluten-free Diet on Clinical Symptoms and the Intestinal Mucosa of Patients With Potential Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 654–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperatore, N.; Tortora, R.; De Palma, G.D.; Capone, P.; Gerbino, N.; Donetto, S.; Testa, A.; Caporaso, N.; Rispo, A. Beneficial effects of gluten free diet in potential coeliac disease in adult population. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | Sex | Age at Diagnosis (years) | Follow-Up Duration (years) | Familiarity for CD | Marsh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | 171 | F 60% | 6 (1.6–17) | 3 (0.35–15.3) | Yes 35% | 0–50% 1–50% |

| Only anti-Tg2 persistently + patients | 134 | F 57% | 5.9 (1.6–17) | 3.19 (0.35–15.3) | Yes 36% | 0–46% 1–54% |

| Only patients with a follow-up > 3 years | 75 | F 65% | 5.7 (1.5–13.3) | 5.7 (3.01–15.3) | Yes 36% | 0–43% 1–57% |

| Only Anti-Tg2 Persistently Seropositive Patients (N = 134, 78%) | Only Patients with a Follow-Up > 3 Years (N = 75, 44%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value T0 | Mean Value Tx | p-Value | Mean Value T0 | Mean Value Tx | p-Value | ||

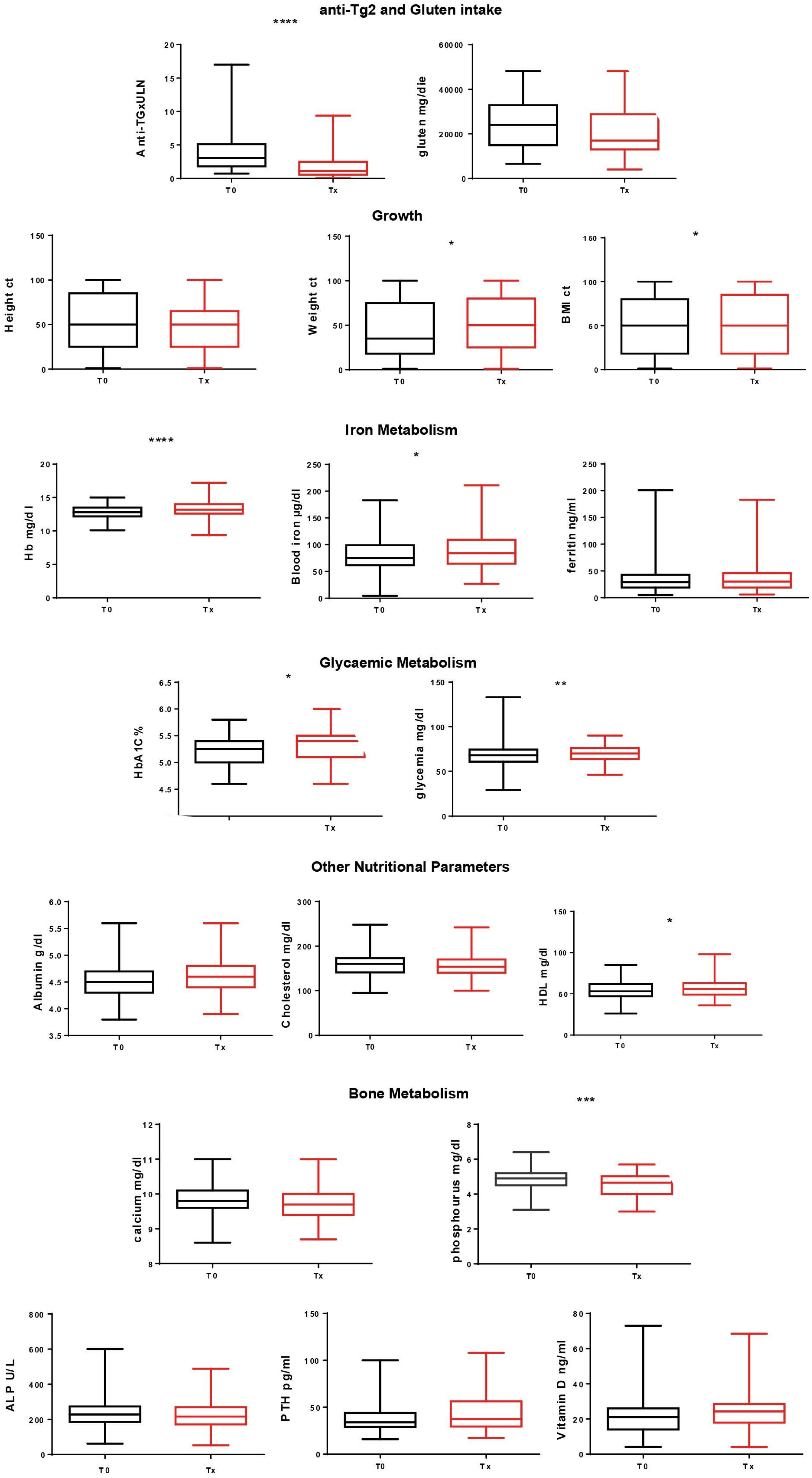

| Anti-Tg2 and gluten intake | Anti-Tg (x ULN) | 3.9 | 2.2 | <0.005 | 4.2 | 1.9 | <0.005 |

| Gluten (g/day) | 23 | 21 | 0.2 | 22.8 | 21.5 | 0.47 | |

| Growth | Height (ct) | 50.5 | 48.6 | 0.25 | 54.08 | 49.2 | 0.05 |

| Weight (ct) | 47.2 | 50.6 | 0.09 | 50.01 | 55.7 | 0.11 | |

| BMI (ct) | 49.7 | 51.3 | 0.49 | 49.7 | 59.2 | 0.01 | |

| Iron metabolism | Hb (mg/dL) | 12.8 | 13.3 | <0.005 | 12.8 | 13.4 | <0.005 |

| Blood iron (µg/dL) | 81.6 | 90.8 | 0.03 | 81.7 | 95.6 | 0.02 | |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 34.4 | 35 | 0.8 | 36.8 | 37.8 | 0.76 | |

| Glycemic metabolism | HbA1C (%) | 5.27 | 5.3 | 0.08 | 5.2 | 5.3 | <0.005 |

| Glycaemia (mg/dL) | 67.3 | 70 | 0.008 | 68.3 | 70.9 | 0.07 | |

| Nutritional status | Albumin (g/dL) | 4.57 | 4.59 | 0.43 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.14 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 154.92 | 154.99 | 0.97 | 162.6 | 157.7 | 0.15 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 54.3 | 57.7 | 0.01 | 53.3 | 55.1 | 0.46 | |

| Bone metabolism | Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.8 | 9.7 | 0.06 | 9.9 | 9.65 | <0.005 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.8 | 4.5 | <0.005 | 4.9 | 4.5 | <0.005 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 229 | 218.6 | 0.16 | 226.3 | 215.3 | 0.44 | |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 41.9 | 45.7 | 0.23 | 42.4 | 46.8 | 0.17 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 24.6 | 25.4 | 0.57 | 19.3 | 21.6 | 0.07 | |

| Thyroid autoantibodies | Anti-TG and Anti-TPO | 9 positive (7%) | 11 positive (8.2%) | Ns Ns | 7 positive (9%) | 11 positive (14%) | Ns Ns |

| Type 1 diabetes autoantibodies | Anti-IAA Anti-IA2 Anti-Zn-T8 Anti-GAD | 5 positive (4%) | 4 positive (3%) | Ns Ns Ns Ns | 8 positive (10%) | 4 positive (5%) | Ns Ns Ns Ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandile, R.; Lerro, F.; Carpinelli, M.; D’Antonio, L.; Greco, L.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R. Potential Celiac Disease in Children: Health Status on A Long-Term Gluten-Containing Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111708

Mandile R, Lerro F, Carpinelli M, D’Antonio L, Greco L, Troncone R, Auricchio R. Potential Celiac Disease in Children: Health Status on A Long-Term Gluten-Containing Diet. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111708

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandile, Roberta, Federica Lerro, Martina Carpinelli, Lorenzo D’Antonio, Luigi Greco, Riccardo Troncone, and Renata Auricchio. 2024. "Potential Celiac Disease in Children: Health Status on A Long-Term Gluten-Containing Diet" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111708

APA StyleMandile, R., Lerro, F., Carpinelli, M., D’Antonio, L., Greco, L., Troncone, R., & Auricchio, R. (2024). Potential Celiac Disease in Children: Health Status on A Long-Term Gluten-Containing Diet. Nutrients, 16(11), 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111708