Optimizing Recovery in Elderly Patients: Anabolic Benefits of Glucose Supplementation during the Rehydration Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. The Occurrence of Refeeding Syndrome

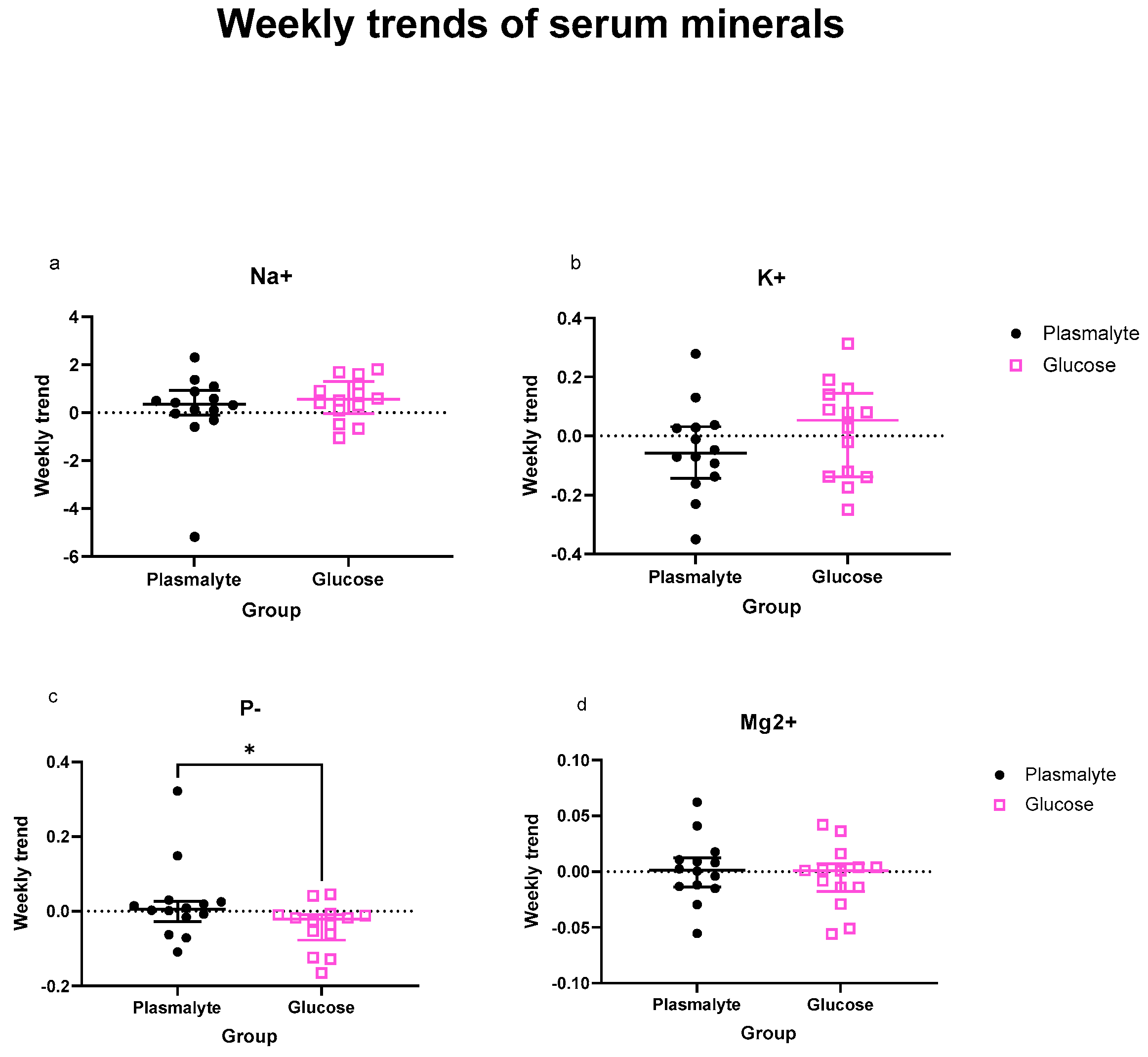

3.3. Trends of Individual Electrolytes in the Serum

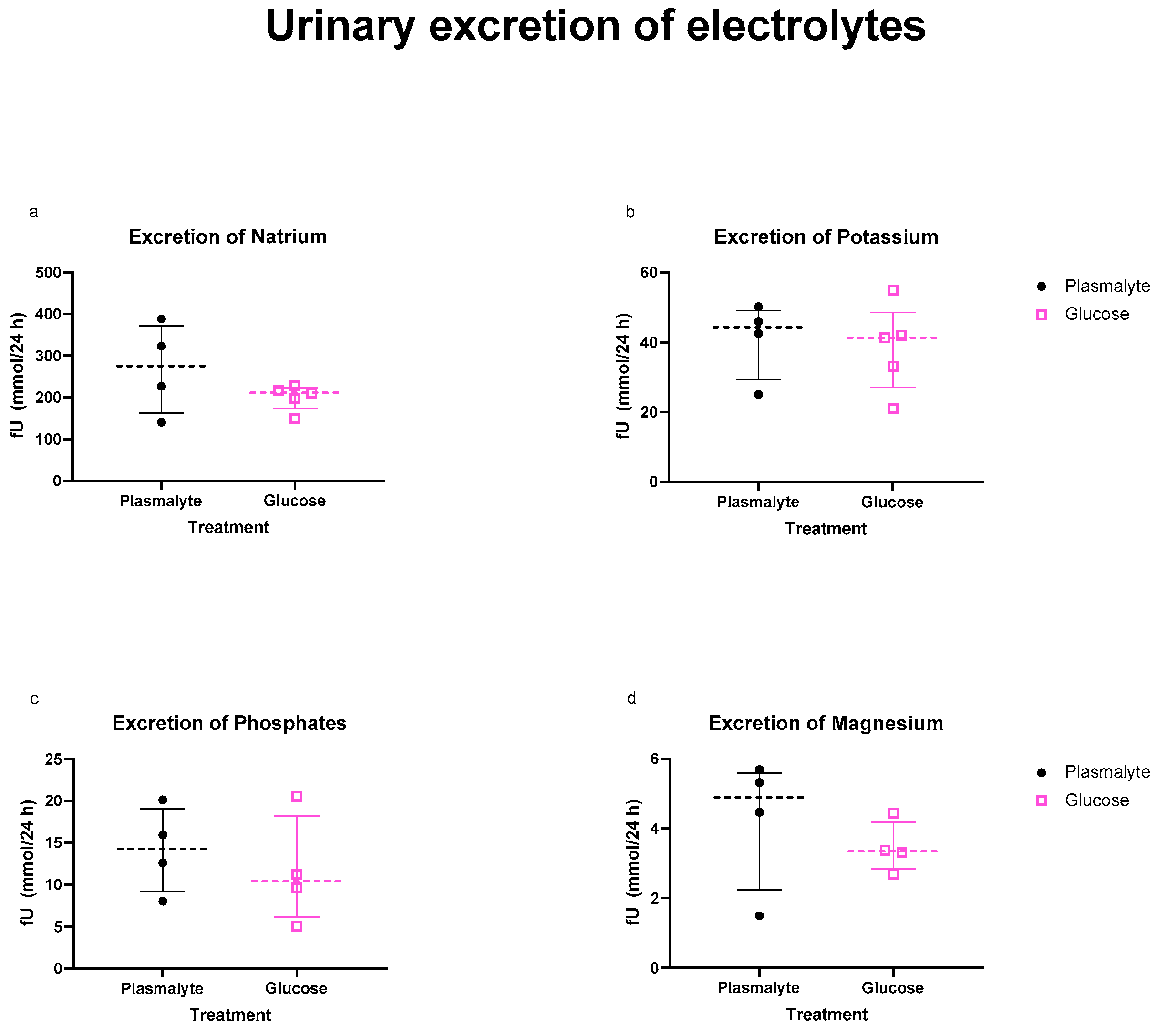

3.4. Electrolytes in the Urine

3.5. Markers of Inflammation

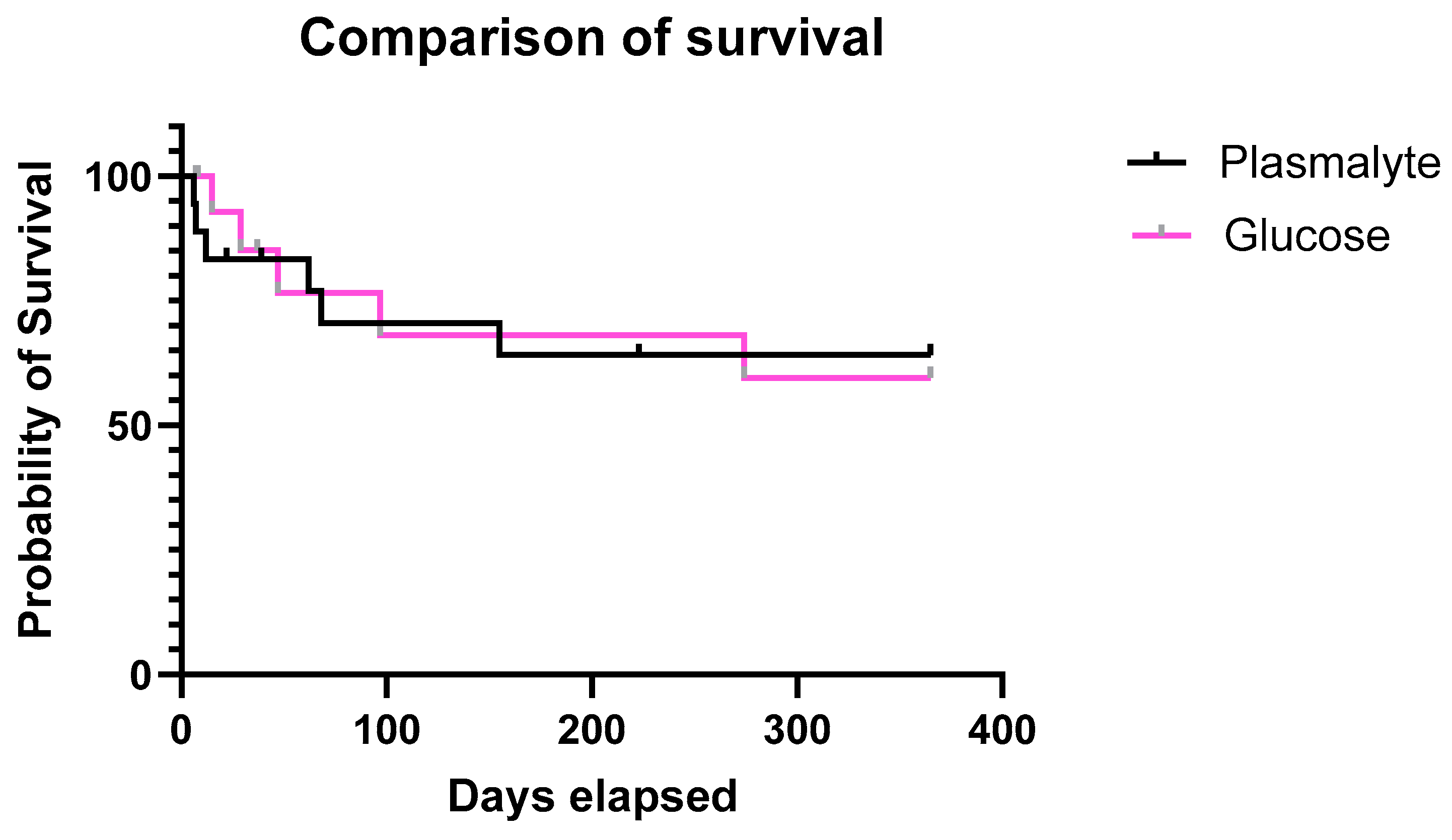

3.6. Further Patients’ Follow Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Clinical Nutrition and Hydration in Geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atciyurt, K.; Heybeli, C.; Smith, L.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P. The Prevalence, Risk Factors and Clinical Implications of Dehydration in Older Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Clin. Belg. 2024, 79, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, K.; Marsden, R.; Paxman, J. Generation of Thirst: A Critical Review of Dehydration among Older Adults Living in Residential Care. Nurs. Resid. Care 2020, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiompanou, E.; Lucas, C.; Stroud, M. Overfeeding and Overhydration in Elderly Medical Patients: Lessons from the Liverpool Care Pathway. Clin. Med. 2013, 13, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.; Fernie, G.; Roshan Fekr, A. Fluid Intake Monitoring Systems for the Elderly: A Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, M.B.; Owen, J.A.; Raymond-Barker, P.; Bishop, C.; Elghenzai, S.; Oliver, S.J.; Walsh, N.P. Is This Elderly Patient Dehydrated? Diagnostic Accuracy of Hydration Assessment Using Physical Signs, Urine, and Saliva Markers. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Self, W.H.; Semler, M.W.; Wanderer, J.P.; Wang, L.; Byrne, D.W.; Collins, S.P.; Slovis, C.M.; Lindsell, C.J.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Siew, E.D.; et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Noncritically Ill Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourhassan, M.; Cuvelier, I.; Gehrke, I.; Marburger, C.; Modreker, M.K.; Volkert, D.; Willschrei, H.P.; Wirth, R. Risk Factors of Refeeding Syndrome in Malnourished Older Hospitalized Patients. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWhirter, J.P.; Pennington, C.R. Incidence and Recognition of Malnutrition in Hospital. BMJ 1994, 308, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edington, J.; Kon, P. Prevalence of Malnutrition in the Community. Nutrition 1997, 13, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, E.; Friedli, N.; Schuetz, P.; Stanga, Z. Refeeding Syndrome in the Frail Elderly Population: Prevention, Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, D.N.; Balagopal, P.; Nair, K.S. Age-Related Sarcopenia in Humans Is Associated with Reduced Synthetic Rates of Specific Muscle Proteins. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 351S–355S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaix, D.; Mosoni, L.; Dardevet, D.; Combaret, L.; Mirand, P.P.; Grizard, J. Altered Responses in Skeletal Muscle Protein Turnover during Aging in Anabolic and Catabolic Periods. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Dickerson, R.N.; Moore, F.A.; Paddon-Jones, D.; Weijs, P.J.M. Protein Turnover and Metabolism in the Elderly Intensive Care Unit Patient. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 112S–120S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.D.; Beigg, C.L.; Macdonald, I.A.; Allison, S.P. A Recipe for Improving Food Intakes in Elderly Hospitalized Patients. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 19, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.D.; Beigg, C.L.; Macdonald, I.A.; Allison, S.P. High Food Wastage and Low Nutritional Intakes in Hospital Patients. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 19, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerová, P.; Dědková, Z.; Sobotka, L. Early Nutritional Support and Physiotherapy Improved Long-Term Self-Sufficiency in Acutely Ill Older Patients. Nutrition 2015, 31, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, L.; Sobotka, O. The Predominant Role of Glucose as a Building Block and Precursor of Reducing Equivalents. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2021, 24, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skořepa, P.; Sobotka, O.; Fortunato, J.; Bláha, V.; Horáček, J.M. The Central Role of Glucose in Metabolism and Nutrition of Critically Ill Patients. Mil. Med. Sci. Lett. 2017, 86, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkalaf, M.; Anděl, M.; Trnka, J. Low Glucose but Not Galactose Enhances Oxidative Mitochondrial Metabolism in C2C12 Myoblasts and Myotubes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dringen, R.; Hoepken, H.H.; Minich, T.; Ruedig, C. 1.3 Pentose Phosphate Pathway and NADPH Metabolism BT—Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology: Brain Energetics. In Integration of Molecular and Cellular Processes; Lajtha, A., Gibson, G.E., Dienel, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 41–62. ISBN 978-0-387-30411-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, L.G.; Lee, P.W.; Brandes, J.L.; Cascante, M.; Muscarella, P.; Schirmer, W.J.; Melvin, W.S.; Ellison, E.C. Nonoxidative Pentose Phosphate Pathways and Their Direct Role in Ribose Synthesis in Tumors: Is Cancer a Disease of Cellular Glucose Metabolism? Med. Hypotheses 1998, 50, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halse, R.; Bonavaud, S.M.; Armstrong, J.L.; McCormack, J.G.; Yeaman, S.J. Control of Glycogen Synthesis by Glucose, Glycogen, and Insulin in Cultured Human Muscle Cells. Diabetes 2001, 50, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarouk, K.O.; Ahmed, S.B.M.; Elliott, R.L.; Benoit, A.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Bashir, A.H.H.; Alhoufie, S.T.S.; Elhassan, G.O.; Wales, C.C.; et al. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Dynamics in Cancer and Its Dependency on Intracellular PH. Metabolites 2020, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kather, H.; Rivera, M.; Brand, K. Interrelationship and Control of Glucose Metabolism and Lipogenesis in Isolated Fat-Cells. Effect of the Amount of Glucose Uptake on the Rates of the Pentose Phosphate Cycle and of Fatty Acid Synthesis. Biochem. J. 1972, 128, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T.A.; O’Keefe, S.J.; Callanan, M.; Marks, T. The Effect of Severe Undernutrition and Subsequent Refeeding on Whole-Body Metabolism and Protein Synthesis in Human Subjects. J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2005, 29, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, R.S. Refeeding Syndrome: Screening, Incidence, and Treatment during Parenteral Nutrition. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28 (Suppl. S4), 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, G.; Goldin, J. The Refeeding Syndrome and Glucose Load. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 44, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, E.; Friedli, N.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Schuetz, P.; Stanga, Z. Management of Refeeding Syndrome in Medical Inpatients. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.U.; Hesseberg, K.; Aas, A.M.; Ranhoff, A.H.; Bye, A. Refeeding Syndrome Occurs among Older Adults Regardless of Refeeding Rates: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Res. 2021, 91, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubart, E.; Leibovitz, A.; Dror, Y.; Katz, E.; Segal, R. Mortality after Nasogastric Tube Feeding Initiation in Long-Term Care Elderly with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia--the Contribution of Refeeding Syndrome. Gerontology 2009, 55, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedli, N.; Stanga, Z.; Culkin, A.; Crook, M.; Laviano, A.; Sobotka, L.; Kressig, R.W.; Kondrup, J.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Management and Prevention of Refeeding Syndrome in Medical Inpatients: An Evidence-Based and Consensus-Supported Algorithm. Nutrition 2018, 47, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, T.E.; Gabe, S.M. Artificial Nutrition and Nutrition Support and Refeeding Syndrome. Medicine 2019, 47, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M.B. Caloric Value of Inulin and Oligofructose. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1436S–1437S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Instutite for Health and Care Excellence. Nutrition Support for Adults: Oral Nutrition Support, Enteral Tube Feeding and Parenteral Nutrition; National Instutite for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Doig, G.S.; Simpson, F.; Heighes, P.T.; Bellomo, R.; Chesher, D.; Caterson, I.D.; Reade, M.C.; Harrigan, P.W.J. Restricted versus Continued Standard Caloric Intake during the Management of Refeeding Syndrome in Critically Ill Adults: A Randomised, Parallel-Group, Multicentre, Single-Blind Controlled Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olthof, L.E.; Koekkoek, W.A.C.K.; van Setten, C.; Kars, J.C.N.; van Blokland, D.; van Zanten, A.R.H. Impact of Caloric Intake in Critically Ill Patients with, and without, Refeeding Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarota, G.; Cesaro, P.; Cazzato, A.; Cianci, R.; Fedeli, P.; Ojetti, V.; Certo, M.; Sparano, L.; Giovannini, S.; Larocca, L.M.; et al. The Water Immersion Technique Is Easy to Learn for Routine Use during EGD for Duodenal Villous Evaluation: A Single-Center 2-Year Experience. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2009, 43, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Long, Q.; Chen, F.; Zhang, T.; Lu, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, L. Nutrition Management of Congenital Glucose-Galactose Malabsorption: Case Report of a Chinese Infant. Medicine 2019, 98, e16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allingstrup, M.J.; Esmailzadeh, N.; Wilkens Knudsen, A.; Espersen, K.; Hartvig Jensen, T.; Wiis, J.; Perner, A.; Kondrup, J. Provision of Protein and Energy in Relation to Measured Requirements in Intensive Care Patients. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; Phillips, S.; Sieber, C.; Stehle, P.; Teta, D.; et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Optimal Dietary Protein Intake in Older People: A Position Paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, L. Nutritional Support in Geriatric Patients: The ESPEN New Recommended Guidelines. Vnitr. Lek. 2018, 64, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, J.; Thomas, A.C.Q.; Phillips, S.M. Muscle Mass Loss in the Older Critically Ill Population: Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2020, 35, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doig, G.S.; Simpson, F.; Sweetman, E.A.; Finfer, S.R.; Cooper, D.J.; Heighes, P.T.; Davies, A.R.; O’Leary, M.; Solano, T.; Peake, S. Early Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Patients with Short-Term Relative Contraindications to Early Enteral Nutrition: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2013, 309, 2130–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, D.A.; Kirn, D.R.; Koochek, A.; Zhu, H.; Travison, T.G.; Reid, K.F.; von Berens, Å.; Melin, M.; Cederholm, T.; Gustafsson, T.; et al. Nutritional Supplementation With Physical Activity Improves Muscle Composition in Mobility-Limited Older Adults, The VIVE2 Study: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 73, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constituent 1 | PlasmaLyte (P) | Added Glucose (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 140 | 140.1 |

| K+ | 5 | 5.1 |

| Ca2+ | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Mg2+ | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Cl− | 98 | 110.8 |

| P5− | - | - |

| Gluconate | 23 | 16.9 |

| Acetate | 27 | 19.8 |

| Glucose (g L−1) | 0 | 100.9 |

| Osmolality (mOsm L−1) | 295 | 832 |

| Parameter | PlasmaLyte (P) | Glucose (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 18 | 16 |

| Age | 85.0 (3.5) 1 | 85.0 (6.8) |

| Men/women | 9/9 | 3/9 |

| Body mass index | 26.0 (5.2) | 24.5 (4.3) |

| Clinical signs of dehydration at admission | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.8) |

| Number of acute diagnoses at admission | 5.0 (3.5) | 5.0 (4.0) |

| Length of hospital stay | 11.5 (5.8) | 9.0 (6.5) |

| In-hospital mortality | 3 (16.7) | 3 (18.8) |

| Barthel’s index (ADL) | 10.5 (50.5) | 22.5 (62.5) |

| Norton’s score of pressure ulcer risk | 18.5 (18.3) | 20.0 (26.0) |

| Baseline glycaemia (mmol L−1) | 7.6 (2.4) | 7.2 (3.5) |

| Baseline osmolality (mOsm L−1) | 284.0 (15.0) | 286.5 (22.0) |

| Baseline natrium (mmol L−1) | 138 (5.0) | 137 (7.8) |

| Baseline potassium (mmol L−1) | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.8) |

| Baseline magnesium (mmol L−1) | 0.74 (0.14) | 0.86 (0.15) |

| Baseline phosphates (mmol L−1) | 0.94 (0.26) | 0.99 (0.27) |

| Baseline urea (mmol L−1) | 7.0 (6.6) | 7.8 (3.7) |

| Baseline creatinine (µmol L−1) | 87.0 (26.0) | 102.5 (70.0) |

| Baseline CRP (mg L−1) | 78.1 (132.8) | 58.3 (99.4) |

| Baseline leukocyte count (×109 L−1) | 10.6 (6.5) | 10.7 (7.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobotka, O.; Mezera, V.; Blaha, V.; Skorepa, P.; Fortunato, J.; Sobotka, L. Optimizing Recovery in Elderly Patients: Anabolic Benefits of Glucose Supplementation during the Rehydration Period. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111607

Sobotka O, Mezera V, Blaha V, Skorepa P, Fortunato J, Sobotka L. Optimizing Recovery in Elderly Patients: Anabolic Benefits of Glucose Supplementation during the Rehydration Period. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111607

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobotka, Ondrej, Vojtech Mezera, Vladimir Blaha, Pavel Skorepa, Joao Fortunato, and Lubos Sobotka. 2024. "Optimizing Recovery in Elderly Patients: Anabolic Benefits of Glucose Supplementation during the Rehydration Period" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111607

APA StyleSobotka, O., Mezera, V., Blaha, V., Skorepa, P., Fortunato, J., & Sobotka, L. (2024). Optimizing Recovery in Elderly Patients: Anabolic Benefits of Glucose Supplementation during the Rehydration Period. Nutrients, 16(11), 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111607