Feasibility and Safety of the Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Asian Infants with Eczema

Abstract

1. Introduction

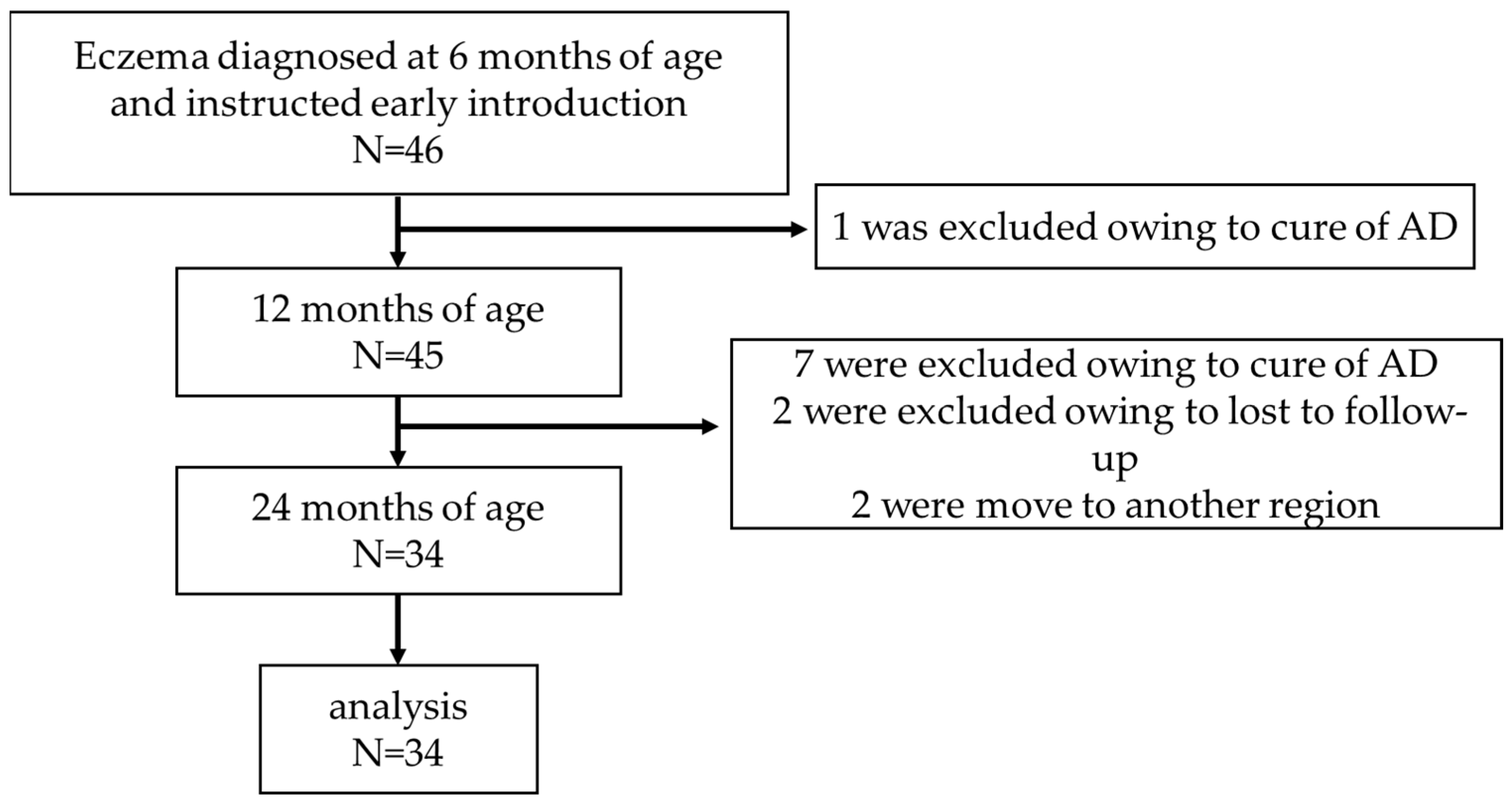

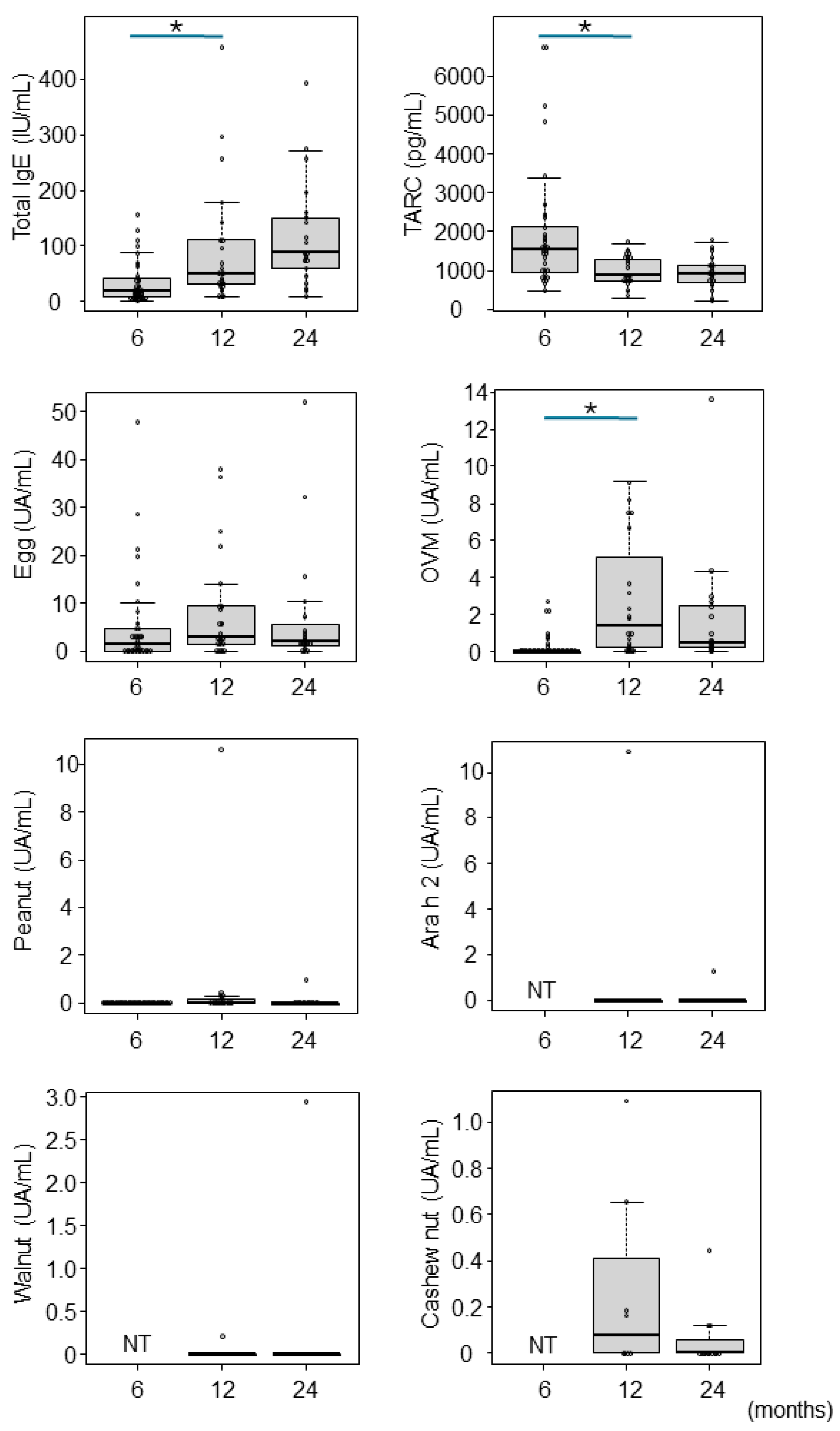

2. Materials and Methods

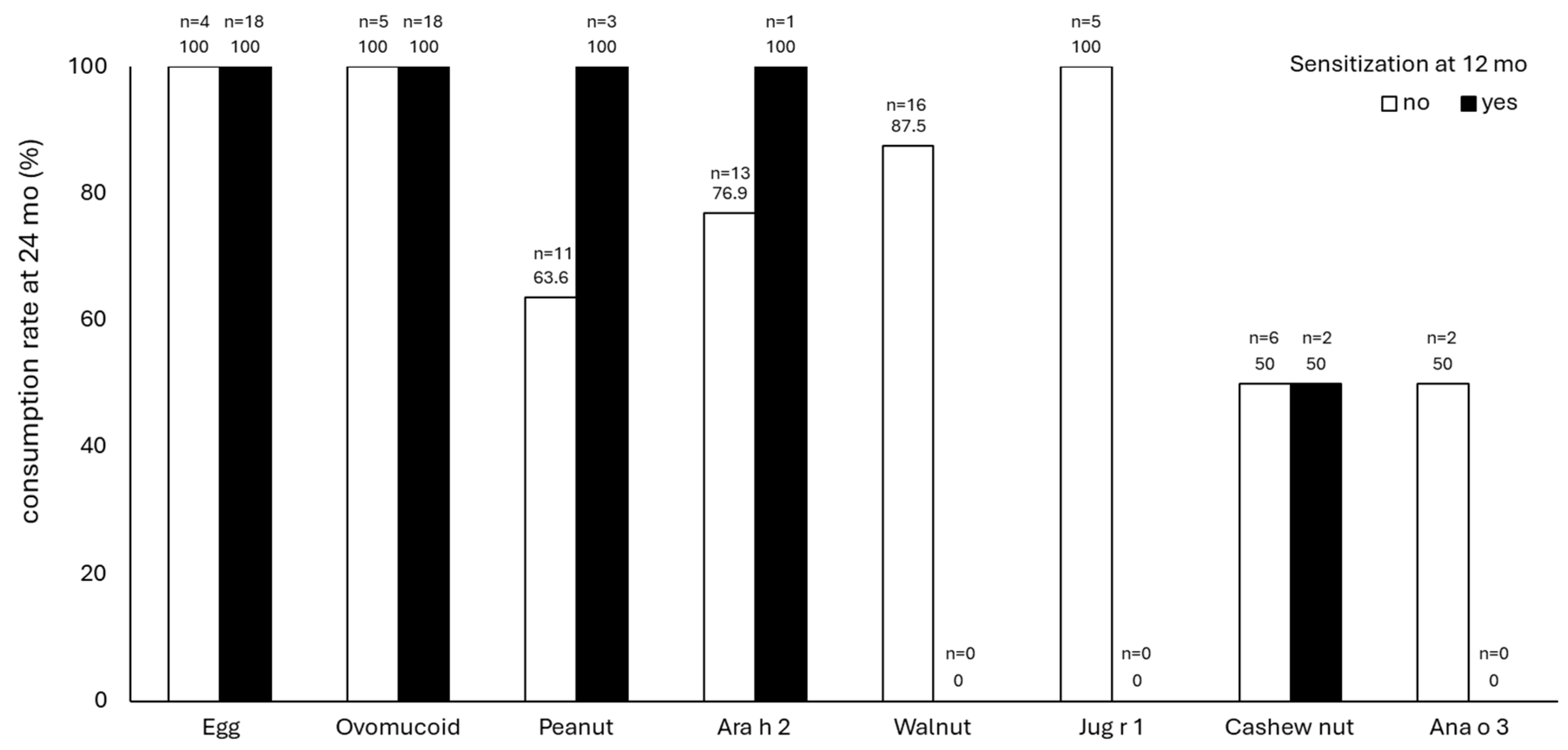

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loh, W.; Tang, M.L.K. The Epidemiology of Food Allergy in the Global Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.M.; Kim, E.H.; Nadeau, K.C.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Wood, R.A.; Sampson, H.A.; Scurlock, A.M.; Chinthrajah, S.; Wang, J.; Pesek, R.D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Immunotherapy in Children Aged 1–3 Years with Peanut Allergy (the Immune Tolerance Network IMPACT Trial): A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Study. Lancet 2022, 399, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsume, O.; Kabashima, S.; Nakazato, J.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Narita, M.; Kondo, M.; Saito, M.; Kishino, A.; Takimoto, T.; Inoue, E.; et al. Two-Step Egg Introduction for Prevention of Egg Allergy in High-Risk Infants with Eczema (PETIT): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Toit, G.; Roberts, G.; Sayre, P.H.; Bahnson, H.T.; Radulovic, S.; Santos, A.F.; Brough, H.A.; Phippard, D.; Basting, M.; Feeney, M.; et al. Randomized Trial of Peanut Consumption in Infants at Risk for Peanut Allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakihara, T.; Otsuji, K.; Arakaki, Y.; Hamada, K.; Sugiura, S.; Ito, K. Randomized Trial of Early Infant Formula Introduction to Prevent Cow’s Milk Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 224–232.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Fukazawa, M.; Fukuoka, K.; Okasora, T.; Yamada, S.; Kyo, S.; Homan, M.; Miura, T.; Nomura, Y.; Tsuchida, S.; et al. Early Introduction of Very Small Amounts of Multiple Foods to Infants: A Randomized Trial. Allergol. Int. 2022, 71, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkin, M.R.; Logan, K.; Tseng, A.; Raji, B.; Ayis, S.; Peacock, J.; Brough, H.; Marrs, T.; Radulovic, S.; Craven, J.; et al. Randomized Trial of Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Breast-Fed Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpone, R.; Kimkool, P.; Ierodiakonou, D.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Perkin, M.R.; Boyle, R.J. Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction and Risk of Immunoglobulin E-Mediated Food Allergy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidyatillake, N.T.; Dharmage, S.C.; Allen, K.J.; Bowatte, G.; Boyle, R.J.; Burgess, J.A.; Koplin, J.J.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Lowe, A.J.; Lodge, C.J. Association between the Age of Solid Food Introduction and Eczema: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 1000–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.E.; Eckert, J.K.; Koplin, J.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Gurrin, L.C.; Dharmage, S.C.; Vuillermin, P.; Tang, M.L.K.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Matheson, M.; et al. Which Infants with Eczema Are at Risk of Food Allergy? Results from a Population-Based Cohort. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, K.; Haruna, M. Short-Term Skin Problems in Infants Aged 0–3 Months Affect Food Allergies or Atopic Dermatitis until 2 Years of Age, among Infants of the General Population. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Yang, L.; Saito-Abe, M.; Sato, M.; Mezawa, H.; Nishizato, M.; Kato, N.; Ito, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; et al. Persistent Eczema Leads to Both Impaired Growth and Food Allergy: JECS Birth Cohort. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Depner, M.; Karvonen, A.M.; Renz, H.; Braun-Fahrländer, C.; Schmausser-Hechfellner, E.; Pekkanen, J.; Riedler, J.; Dalphin, J.-C.; et al. Phenotypes of Atopic Dermatitis Depending on the Timing of Onset and Progression in Childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Ohya, Y. Skin and Oral Intervention for Food Allergy Prevention Based on the Dual Allergen Exposure Hypothesis. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, E.H.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Leung, A.S.Y.; Ohya, Y. Role of Skin Management in the Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, K.; Ito, T.; Ito, K. Comprehensive Hospital-Based Regional Survey of Anaphylaxis in Japanese Children: Time Trends of Triggers and Adrenaline Use. Allergol. Int. 2021, 70, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togias, A.; Cooper, S.F.; Acebal, M.L.; Assa’ad, A.; Baker, J.R.; Beck, L.A.; Block, J.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Chan, E.S.; Eichenfield, L.F.; et al. Addendum Guidelines for the Prevention of Peanut Allergy in the United States: Report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-Sponsored Expert Panel. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quake, A.Z.; Liu, T.A.; D’Souza, R.; Jackson, K.G.; Woch, M.; Tetteh, A.; Sampath, V.; Nadeau, K.C.; Sindher, S.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; et al. Early Introduction of Multi-Allergen Mixture for Prevention of Food Allergy: Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.L.; Barret, D.Y.; Soriano, V.X.; McWilliam, V.; Lowe, A.J.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Tang, M.L.K.; Dharmage, S.C.; Gurrin, L.C.; Koplin, J.J.; et al. No Cashew Allergy in Infants Introduced to Cashew by Age 1 Year. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Warren, C.; Samady, W.; Nimmagadda, S.R.; Vincent, E.; Zaslavsky, J.; Bilaver, L.; Gupta, R. Food Allergen Introduction Patterns in the First Year of Life: A US Nationwide Survey. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.A.; Smith, J.; Vale, S.; Campbell, D.E. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy Infant Feeding for Allergy Prevention Guidelines. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, V.X.; Peters, R.L.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Dharmage, S.C.; Perrett, K.P.; Field, M.J.; Knox, A.; Tey, D.; Odoi, S.; Gell, G.; et al. Earlier Ingestion of Peanut after Changes to Infant Feeding Guidelines: The EarlyNuts Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1327–1335.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manti, S.; Galletta, F.; Bencivenga, C.L.; Bettini, I.; Klain, A.; D’Addio, E.; Mori, F.; Licari, A.; Miraglia Del Giudice, M.; Indolfi, C. Food Allergy Risk: A Comprehensive Review of Maternal Interventions for Food Allergy Prevention. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, S.; Galletta, F.; Leonardi, S. Editorial: Nutrition, Diet and Allergic Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1359005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, M.; Hayashi, D.; Kajita, N.; Kinoshita, M.; Ishii, T.; Tsumura, Y.; Horimukai, K.; Yoshida, K.; Takahashi, T.; Morita, H. Recent Dramatic Increase in Patients with Food Protein–Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES) Provoked by Hen’s Egg in Japan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1110–1112.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, Y.; Ishii, T.; Morita, K.; Tsumura, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Akashi, M.; Morita, H. Multicenter Retrospective Study of Patients with Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Provoked by Hen’s Egg. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 547–549.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Pak, K.; Saito-Abe, M.; Sato, M.; Miyaji, Y.; Mezawa, H.; Nishizato, M.; Yang, L.; Kumasaka, N.; Nomura, I.; et al. Prenatal Antibiotic Use, Caesarean Delivery and Offspring’s Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome: A National Birth Cohort (JECS). Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Ohya, Y. Overviewing Allergy Epidemiology in Japan—Findings from Birth Cohorts (JECS and T-Child Study). Allergol. Int. 2024, 73, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli Sopo, S.; Mastellone, F.; Bersani, G.; Gelsomino, M. Personalization of Complementary Feeding in Children With Acute Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 620–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Pak, K.; Iwamoto, S.; Konishi, M.; Saito-Abe, M.; Sato, M.; Miyaji, Y.; Mezawa, H.; Nishizato, M.; Yang, L.; et al. Parental Stress and Food Allergy Phenotypes in Young Children: A National Birth Cohort (JECS). Allergy, 2024; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Abe, M.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Pak, K.; Iwamoto, S.; Sato, M.; Miyaji, Y.; Mezawa, H.; Nishizato, M.; Yang, L.; Kumasaka, N.; et al. How a Family History of Allergic Diseases Influences Food Allergy in Children: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaji, Y.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Yang, L.; Fukuie, T.; Narita, M.; Ohya, Y. Effectiveness and Safety of Low-Dose Oral Immunotherapy Protocols in Paediatric Milk and Egg Allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 1307–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K.; Yang, L.; Inuzuka, Y.; Ishikawa, F.; Fukuie, T.; Ohya, Y. Predictors of Oral Food Challenge Outcome in Young Children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2024, 54, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Hen’s Egg | Peanuts | p-Value | Walnuts | p | Cashew Nuts | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid response (n) | 34 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 29 | ||||||

| Early introduction | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| Male (%) | 22 (64.7) | 22 (64.7) | 4 (12.1) | 17 (51.5) | 2 (6.3) | 18 (56.3) | 8 (27.6) | 9 (31.0) | |||

| Mother’s history of FA | 7 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0.62 | 1 | 6 | 1.0 | 5 | 2 | 0.67 |

| Father’s history of FA | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.56 | 0 | 5 | 0.56 | 2 | 3 | 0.62 |

| Older sibling’s FA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0.41 |

| IGA 6mo (median, range) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–3) | 0.09 | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 0.56 | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 0.57 |

| IGA 12mo (median, range) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.5 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.79 | 0.5 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.54 | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.41 |

| IGA 24mo (median, range) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.5 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.54 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.67 | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.15 |

| POEM (median, range) | 1.5 (0–17) | 1.5 (0–17) | 3 (0–11) | 1 (0–17) | 0.80 | 2.5 (0–11) | 2 (0–17) | 0.90 | 2 (0–16) | 1 (0–17) | 0.62 |

| EASI (median, range) | 0 (0–12.4) | 0 (0–12.4) | 0 (0–4.5) | 0 (0–12.4) | 0.25 | 0 (0–4.5) | 0 (0–12.4) | 0.34 | 0 (0–7.6) | 0 (0–12.4) | 0.49 |

| Total | Hen’s Egg | Peanuts | Walnuts | Cashew Nuts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid response (n) | 34 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 29 | |||

| Early introduction | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Choking or aspiration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Episode of allergy reactions related target allergenic foods | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Food hypersensitivity-related ER visit for any foods | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Unscheduled visit regarding any foods | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Adrenaline use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Episode of any food allergy (%) | 8 (23.5) | 8 (23.5) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (26.9) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (26.9) | 4 (23.5) | 4 (33.3) |

| Episode of any FPIES (%) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 2 (7.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (8.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harama, D.; Saito-Abe, M.; Hamaguchi, S.; Fukuie, T.; Ohya, Y.; Yamamoto-Hanada, K. Feasibility and Safety of the Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Asian Infants with Eczema. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111578

Harama D, Saito-Abe M, Hamaguchi S, Fukuie T, Ohya Y, Yamamoto-Hanada K. Feasibility and Safety of the Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Asian Infants with Eczema. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111578

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarama, Daisuke, Mayako Saito-Abe, Sayaka Hamaguchi, Tatsuki Fukuie, Yukihiro Ohya, and Kiwako Yamamoto-Hanada. 2024. "Feasibility and Safety of the Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Asian Infants with Eczema" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111578

APA StyleHarama, D., Saito-Abe, M., Hamaguchi, S., Fukuie, T., Ohya, Y., & Yamamoto-Hanada, K. (2024). Feasibility and Safety of the Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Asian Infants with Eczema. Nutrients, 16(11), 1578. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111578