Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies—A Commonly Reported Problem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Growth and Dietary Intake

2.3. Assessment of Feeding Difficulties

2.4. Ethics, Consent, and Permissions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prescott, S.; Allen, K.J. Food allergy: Riding the second wave of the allergy epidemic. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Pawankar, R.; Allen, K.J.; E Campbell, D.; Sinn, J.K.; Fiocchi, A.; Ebisawa, M.; Sampson, H.A.; Beyer, K.; Lee, B.-W. A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. World Allergy Organ. J. 2013, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Akdis, M.; Chivato, T.; del Giacco, S.; Gajdanowicz, P.; Gracia, I.E.; Klimek, L.; Lauerma, A.; et al. Nomenclature of allergic diseases and hypersensitivity reactions: Adapted to modern needs: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2023, 78, 2851–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, A.; Bognanni, A.; Brożek, J.; Ebisawa, M.; Schünemann, H.; WAO DRACMA Guideline Group. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 21 (Suppl. 21), 1–125. [Google Scholar]

- NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel; Boyce, J.A.; Assa, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126 (Suppl. 6), S1–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyt, D.; Ball, H.; Makwana, N.; Green, M.R.; Bravin, K.; Nasser, S.M.; Clark, A.T.; Standards of Care Committee (SOCC) of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI). BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 642–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas, Y.; Broekaert, I.; Domellöf, M.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; Pienar, C.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Thapar, N.; et al. An ESPGHAN position paper on the diagnosis, management and prevention of cow’s milk allergy. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslin, K.; Dean, T.; Arshad, S.H.; Venter, C. Fussy eating and feeding difficulties in infants and toddlers consuming a cows’ milk exclusion diet. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 26, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.-A.; Nurmatov, U.; DunnGalvin, A.; Reese, I.; Vieira, M.C.; Rommel, N.; Dupont, C.; Venter, C.; Cianferoni, A.; Walsh, J.; et al. EAACI Task Force on feeding difficulties in children with food allergies: A systematic review. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.; Rommel, N.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Fleming, C.; Dziubak, R.; Shah, N. Feeding difficulties in children with food protein-induced gastrointestinal allergies. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 1764–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkada, V.A.; Haas, A.; Maune, N.C.; Capocelli, K.E.; Henry, M.; Gilman, N.; Petersburg, S.; Moore, W.; Lovell, M.A.; Fleischer, D.M.; et al. Feeding Dysfunction in Children with Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Pediatrics 2011, 126, e672–e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Furuta, G.T.; Brennan, T.; Henry, M.L.; Maune, N.C.; Sundaram, S.S.; Menard-Katcher, C.; Atkins, D.; Takurukura, F.; Giffen, S.; et al. Nutritional State and Feeding Behaviors of Children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozinsky, A.C.; Meyer, R.; De Koker, C.; Dziubak, R.; Godwin, H.; Reeve, K.; Ortega, G.D.; Shah, N. Time to symptom improvement using elimination diets in non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 26, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.M.; Parkinson, K.N.; Shipton, D.; Drewett, R.F. How Do Toddler Eating Problems Relate to Their Eating Behavior, Food Preferences, and Growth? Pediatrics 2007, 120, e1069–e1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, M.; Meyer, R.; Beauregard, A. Feeding Difficulties in Children with non–IgE-Mediated Food Allergic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Ann. Allergy 2019, 122, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R. Nutritional disorders resulting from food allergy in children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’auria, E.; Cattaneo, C.; Panelli, S.; Pozzi, C.; Acunzo, M.; Papaleo, S.; Comandatore, F.; Mameli, C.; Bandi, C.; Zuccotti, G.; et al. Alteration of taste perception, food neophobia and oral microbiota composition in children with food allergy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flom, J.D.; Groetch, M.; Kovtun, K.; Westcott-Chavez, A.; Schultz, F.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Feeding difficulties in children with food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2939–2941.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, R.; Mukkada, V.; Smith, A.; Pitts, T. Optimizing an Aversion Feeding Therapy Protocol for a Child with Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES). J. Pulm. Respir. Med. 2015, 5, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zangen, T.; Ciarla, C.; Zangen, S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Flores, A.F.; Cocjin, J.; Reddy, S.N.; Rowhani, A.; Schwankovsky, L.; Hyman, P.E. Gastrointestinal motility and sensory abnormalities may contribute to food refusal in medically fragile toddlers 2. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2003, 37, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Nieves, D.; Conley, A.; Nagib, K.; Shannon, K.; Horvath, K.; Mehta, D. Gastrointestinal Conditions in Children with Severe Feeding Difficulties. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 6, 2333794X19838536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiem, M.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U. Intestinal Barrier Permeability in Allergic Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinai, T.; Goldberg, M.R.; Nachshon, L.; Amitzur-Levy, R.; Yichie, T.; Katz, Y.; Monsonego-Ornan, E.; Elizur, A. Reduced Final Height and Inadequate Nutritional Intake in Cow’s Milk-Allergic Young Adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.; Koplin, J.; Dharmage, S.; Wake, M.; Gurrin, L.; McWilliam, V.; Tang, M.; Sun, C.; Foskey, R.; Allen, K.J.; et al. Persistent Food Allergy and Food Allergy Coexistent with Eczema Is Associated with Reduced Growth in the First 4 Years of Life. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2016, 4, 248–256.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Harris, G.; Emmet, P. Delayed introduction of lumpy foods to children during the complementary feeding period affects child’s food acceptance and feeding at 7 years of age. Matern. Child Nutr. 2009, 5, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G. Development of taste and food preferences in children. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, M.; Martel, C.; Porporino, M.; Zygmuntowicz, C. The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale: A brief bilingual screening tool for identifying feeding problems. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 16, 147–151+e16–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.M.; Parkinson, K.N.; Drewett, R.F. How does maternal and child feeding behavior relate to weight gain and failure to thrive? Data from a prospective birth cohort. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feeding Difficulties |

|---|

| Regular meal refusal (regular defined as daily) |

| Extended mealtimes (defined as >30 min) |

| Gagging on textured foods |

| Poor appetite |

| Dysphagia (defined as visible signs of struggling to swallow) |

| Difficulties with sucking (breast of bottle) |

| Characteristic | Feeding Difficulties (n = 61) | No Feeding Difficulties (n = 53) | p-Value | Total (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months), median (IQR) | 19.4 (7.7–37.1) | 24.2 (6.5–77.3) | 0.428 | 19.76 (7.4–65.8) |

| Weight-for-age z-score, median (IQR) | −0.13 (−0.90–0.55) | 0.13 (−0.57–0.60) | 0.225 | −0.01 (−0.79–0.58) |

| Height-for-age z-score, median (IQR) | −0.46 (−1.23–0.42) | 0.25 (−0.60–0.71) | 0.022 | −0.27 (−0.83–0.62) |

| Weight-for-height z-score, median (IQR) | 0.10 (−0.52–0.84) | 0.43 (−0.71–0.93) | 0.687 | 0.23 (−0.53–0.89) |

| BMI-for-age z-score, median (IQR) | 0.04 (−0.40–0.63) | 0.12 (−0.77–0.87) | 0.752 | 0.08 (−0.53–0.63) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 37 (60.7) | 39 (73.6) | 0.144 | 76 (66.7) |

| Female | 24 (39.3) | 14 (26.4) | 38 (33.3) | |

| Number of intestinal symptoms, median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 5 (4–6) | 0.007 | 5 (4–6) |

| Number of foods eliminated, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–4) | 0.054 | 3 (2–4) |

| Symptom score before elimination diet, median (IQR) | 22 (16–25)/45 | 17 (12–21)/45 | 0.002 | 18 (14–24)/45 |

| Improvement, mean difference Likert scale (SD) | 11.4 (7.1) | 10.1 (6.5) | 0.307 | 10.8 (6.8) |

| Length of elimination diet (weeks), median (IQR) | 17.4 (11.7–34.8) | 10.3 (7.3–21.7) | 0.021 | 13.0 (8.7–32.6) |

| Feeding Difficulties | Number/Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Regular mean refusals | 29/108 (26.9) |

| Extended mealtimes | 28/105 (26.7) |

| Gagging on textured foods | 30/113 (26.5) |

| Poor appetite | 21/113 (18.6) |

| Dysphagia | 19/113 (16.8) |

| Breast/bottle feeding difficulties | 4/113 (3.5) |

| Number of feeding difficulties | |

| 0 | 53/114 (46.5) |

| 1 | 21/114 (18.4) |

| 2 | 19/114 (16.7) |

| 3 | 13/114 (11.4) |

| 4 | 4/114 (3.5) |

| 5 | 4/114 (3.5) |

| Symptoms | Feeding Difficulties (n = 61) | No Feeding Difficulties (n = 53) | p-Value | Total (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 54 (88.5) | 48 (90.6) | 0.723 | 102 (89.5) |

| Flatus | 52 (85.2) | 44 (83.0) | 0.745 | 96 (84.2) |

| Bloating | 39 (63.9) | 27 (50.9) | 0.161 | 66 (57.9) |

| Diarrhoea | 33 (54.1) | 29 (54.7) | 0.947 | 62 (54.4) |

| Vomiting | 39 (63.9) | 22 (41.5) | 0.017 | 61 (53.5) |

| Constipation | 37 (60.7) | 19 (35.8) | 0.008 | 56 (49.1) |

| Blood in the stool | 16 (26.2) | 12 (22.6) | 0.657 | 28 (24.6) |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 26 (42.6) | 29/52 (55.8) | 0.163 | 55/113 (48.7) |

| Asthma | 31 (50.8) | 29/52 (55.8) | 0.599 | 60/113 (53.1) |

| Eczema | 47 (77.0) | 36 (67.9) | 0.275 | 83 (72.8) |

| Frequent respiratory infections | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.9) | 1.000 | 3 (2.6) |

| Variable | Initial Model | Final Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

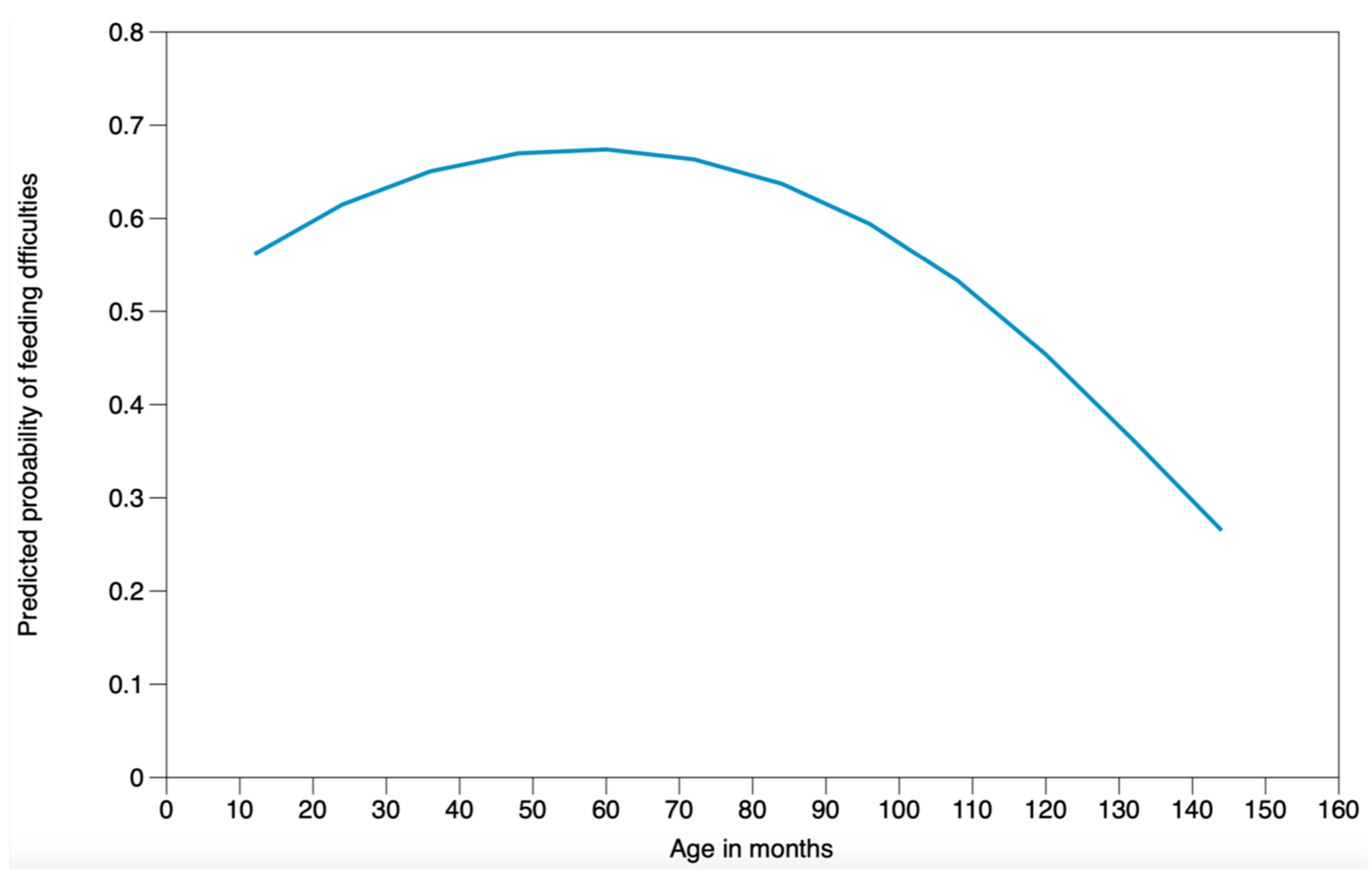

| Age in months | 1.0257 (0.9929–1.0596) | 0.126 | 1.0271 (0.9948–1.0605) | 0.101 |

| Age in months2 | 0.9998 (0.9995–1.0000) | 0.059 | 0.9998 (0.9995–1.0000) | 0.047 |

| Male gender | 0.5871 (0.2476–1.3922) | 0.227 | – | – |

| Initial symptom score | 1.0793 (1.0123–1.1507) | 0.020 | 1.0873 (1.0208–1.1581) | 0.009 |

| Number of foods excluded | 1.0715 (0.0523–3.9249) | 0.504 | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chebar-Lozinsky, A.; De Koker, C.; Dziubak, R.; Rolnik, D.L.; Godwin, H.; Dominguez-Ortega, G.; Skrapac, A.-K.; Gholmie, Y.; Reeve, K.; Shah, N.; et al. Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies—A Commonly Reported Problem. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111563

Chebar-Lozinsky A, De Koker C, Dziubak R, Rolnik DL, Godwin H, Dominguez-Ortega G, Skrapac A-K, Gholmie Y, Reeve K, Shah N, et al. Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies—A Commonly Reported Problem. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111563

Chicago/Turabian StyleChebar-Lozinsky, Adriana, Claire De Koker, Robert Dziubak, Daniel Lorber Rolnik, Heather Godwin, Gloria Dominguez-Ortega, Ana-Kristina Skrapac, Yara Gholmie, Kate Reeve, Neil Shah, and et al. 2024. "Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies—A Commonly Reported Problem" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111563

APA StyleChebar-Lozinsky, A., De Koker, C., Dziubak, R., Rolnik, D. L., Godwin, H., Dominguez-Ortega, G., Skrapac, A.-K., Gholmie, Y., Reeve, K., Shah, N., & Meyer, R. (2024). Assessing Feeding Difficulties in Children Presenting with Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies—A Commonly Reported Problem. Nutrients, 16(11), 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111563